Abstract

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) has two isozymes of the cyanogenic β-glucosidase dhurrinase: dhurrinase-1 (Dhr1) and dhurrinase-2 (Dhr2). A nearly full-length cDNA encoding dhurrinase was isolated from 4-d-old etiolated seedlings and sequenced. The cDNA has a 1695-nucleotide-long open reading frame, which codes for a 565-amino acid-long precursor and a 514-amino acid-long mature protein, respectively. Deduced amino acid sequence of the sorghum Dhr showed 70% identity with two maize (Zea mays) β-glucosidase isozymes. Southern-blot data suggested that β-glu-cosidase is encoded by a small multigene family in sorghum. Northern-blot data indicated that the mRNA corresponding to the cloned Dhr cDNA is present at high levels in the node and upper half of the mesocotyl in etiolated seedlings but at low levels in the root—only in the zone of elongation and the tip region. Light-grown seedling parts had lower levels of Dhr mRNA than those of etiolated seedlings. Immunoblot analysis performed using maize-anti-β-glucosidase sera detected two distinct dhurrinases (57 and 62 kD) in sorghum. The distribution of Dhr activity in different plant parts supports the mRNA and immunoreactive protein data, suggesting that the cloned cDNA corresponds to the Dhr1 (57 kD) isozyme and that the dhr1 gene shows organ-specific expression.

β-Glucosidases (β-d-glucoside glucohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.21) catalyze the hydrolysis of aryl and alkyl β-glucosides, releasing Glc and an aglycone (Reese, 1977). These enzymes occur ubiquitously in plants, fungi, bacteria, and animals (Woodward and Wiseman, 1982). The natural substrates of β-glucosidases include the steroid β-glucosides and β-glucosyl ceramides of mammals, cyanogenic and hydroxamic acid β-glucosides of plant secondary metabolism, and β-linked oligosaccharides released from the digestion of plant cell walls during germination (Conn, 1981; Niemeyer, 1988; Beutler, 1992; Cuevas et al., 1992; Leah et al., 1995). Most β-glucosidases display broad specificity for the aglycone moiety of their substrates but somewhat narrow specificity for the glycone moiety. In fact, β-glucosidases from every source have similar specificity for the glycone (Glc) portion of the substrate, but some enzymes, especially those from plants, differ dramatically in specificity for the aglycone portion (Hösel and Conn, 1982; Hughes and Dunn, 1982; Babcock and Esen, 1994). Babcock and Esen (1994) proposed that a hydrophobic aglycone group is required for cleaving the β-glycosidic bond between the glycone and the aglycone in maize (Zea mays) β-glucosidase. The cyanogenic diglucoside (R)-amygdalin (the gentiobioside of [R]-mandelonitrile) of black cherry and other stone fruits has the disaccharide gentiobiose as its glycone instead of Glc (Poulton, 1993).

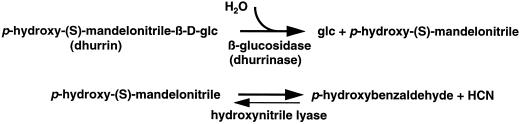

The aglycones, the active group of glucosides, play important roles in plant defense, development, and growth (Selmar et al., 1987; Poulton, 1990). Cyanogenic β-glu-cosides have long been known to be involved in the defense against some pathogens and herbivores, releasing the respiratory poison HCN upon hydrolysis by β-glucosidase (Hruska, 1988; Poulton, 1993). In fact, many important crops, including sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), cassava, lima beans, flax, white clover, rubber tree, and stone fruits, contain cyanogenic β-glucosides and corresponding β-glucosidases (Poulton, 1989). Upon damage to tissues, the enzyme and its substrate, which are compartmentalized in intact tissues, come into contact and release a toxic aglycone or a derivative (e.g. HCN) (Kakes, 1985; Hösel et al., 1987; Selmar, 1993). Under these conditions, dhurrin is hydrolyzed by an endogenous β-glucosidase (dhurrinase) to produce p-hydroxymandelonitrile, which subsequently disassociates to free HCN and p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Hydrolysis of dhurrin by β-glucosidase (dhurrinase) and the production of HCN.

Sorghum has two cyanogenic β-glucosidases, Dhr1 and Dhr2, which were purified by Hösel et al. (1987) and shown to be made up of 57- and 62-kD monomers, respectively. Both enzymes exhibit high specificity for the physiological substrate dhurrin, as well as its structural analog sambunigrin, with Km values of 0.15 and 0.3 mm, respectively (Hösel et al., 1987). However, neither enzyme shows any detectable activity toward any of the other natural or artificial substrates tested, except that Dhr2 shows substantial reactivity toward the synthetic substrates 4MUG and pNPG.

The purpose of this study was to isolate and characterize cDNAs encoding β-glucosidase from sorghum to study their expression and compare them with those of maize as part of our research focusing on β-glucosidase structure and function in grasses. To this end, we cloned and sequenced a β-glucosidase (dhurrinase) cDNA (accession no. U33817) and investigated its multiplicity by Southern-blot analysis and its spatial expression by northern- and western-blot analyses and dhurrinase-activity assays. In addition, the Dhr1 and Dhr2 isozymes were isolated and characterized with respect to substrate specificity and spatial distribution. Our results suggest that the isolated cDNA corresponds to dhurrinase-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) seeds (P-721N) were obtained from Dr. Richard Axtell (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN). Seeds were germinated in vermiculite in darkness (3–4 d) and light (6–7 d) at 25°C. Seedlings were harvested and divided into different parts to isolate total RNA and protein for use in northern- and western-blot analyses and enzyme assays. Etiolated seedlings were divided into the following parts: the coleoptile (which includes the coleoptile proper and the primordial leaves), the node, mesocotyl-2 (upper half, the part below the node), mesocotyl-1 (lower half, the part attached to the germ), root-1 (upper half, the part attached to the germ), and root-2 (lower half, starting with the root tip). Light-grown seedlings were divided into coleoptile, leaves, node, and root-2 (light-grown seedlings do not have a distinct mesocotyl). In addition, whole seedlings were used for genomic DNA isolation.

mRNA Isolation

Total RNA was isolated from 3- to 4-d-old etiolated seedlings using Trizol reagent (GIBCO-BRL, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Typically, 2 g of frozen seedlings was ground in a chilled mortar and suspended in 40 mL of Trizol reagent. After alcohol precipitation and washes, the RNA pellet was resuspended in DEPC-treated water, and 4 m LiCl was added to a final concentration of 1 m. The solution was centrifuged at 18,000g for 15 min at 4°C. Finally, the resulting RNA pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of DEPC-treated water, and the amount of RNA was determined spectrophotometrically. Seventy-five micrograms of total RNA was used for isolation of poly(A+) RNA according to the manufacturer's procedure (Dynall, Oslo, Norway) by affinity chromatography using oligo(dT) that was attached covalently to magnetic beads (Jacobsen et al., 1990).

Reverse Transcription and cDNA Cloning

Ten microliters of eluted poly(A+) RNA was used as a template for reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA using the components of a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (GIBCO-BRL). The reaction mixture included 10 μL of mRNA (approximately 2 μg), 1 μL of 20 μm anchor-linked oligo(dT), 4 μL of 5× first-strand buffer, 1 μL of 0.1 m DTT, 2 μL of 10 mm deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate, 1 μL of RNasin, and 1 μL (200 units) of Superscript RT II (GIBCO-BRL). The reaction was at 48°C for 2 h. The resulting cDNA was purified by binding to a silica matrix in the presence of 6 n NaI according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Purified cDNA was dissolved in 10 μL of DEPC-treated water and used in the 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends experiments.

The nucleotide and amino acid sequences of β-glucosidases from monocot and dicot sources were compared using the Megalign program (DNASTAR, Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI) to locate invariant regions. The oligonucleotide (antisense) primer β-glu27 (CCGATTCCGTTCTCGGTGAT) was derived from the peptide sequence V/YITENG, which makes up part of the catalytic domain and is universally conserved in all of the known β-glucosidases from monocots and other sources. The 3′ end of the first-strand cDNA was ligated to the AmpliFINDER anchor (Clontech) by T4 RNA ligase (Boehringer Mannheim) for the 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends. The 5′ three-fourths of the β-glucosidase cDNA was amplified by PCR using the β-glu27 (antisense) and the second-strand AmpliFINDER anchor (sense) primer pair. An aliquot of the PCR reaction was analyzed on a 1% agarose gel.

A product of approximately 1500 bp was obtained and cloned into the Srf I site of the plasmid vector pCR-Script SK(+) (Stratagene). The construct was used to transform the Escherichia coli strain XL1-Blue, and the white (positive) colonies were screened by PCR using vector-specific (T3 and T7) primers to determine whether they contained an insert of the expected size (Gussow and Clackson, 1989). A large-scale plasmid preparation was made from one of the positive clones and used to sequence the insert. Based on the sequence data from the insert, a gene-specific sense primer (β-glu69, TATGTACCCTAAAGGCCTACAC) was synthesized and used with a second-strand anchor primer, A76 (GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTA), to amplify the 3′ end of the β-glucosidase cDNA. The resulting 3′ end PCR product was sequenced directly, without cloning, using cycle sequencing (Epicenter Technologies, Madison, WI).

Finally, a primer pair (β-glu107, sense, TGAATTCGTGGGCAACTCA and β-glu108, antisense, ATTGCAAATCGATCACTTCGT) derived from the extreme 5′ and 3′ ends of the cDNA was used to amplify the full-length cDNA (1983 bp) and cloned into pCR-Script SK(+). The sequences of the cDNA and its putative protein product were compared with sequences in the GenBank database to confirm their identity and evaluate their similarity to other β-glucosidases.

Probe Synthesis

The second-strand AmpliFINDER anchor primer and β-glu27 were used to amplify the 5′ three-fourths (1446 bp) of the cDNA by PCR to serve as a 5′ probe. This probe spans the first 10 of the 12 exons that are expected to occur in dhurrinase genes based on the structure and organization of the maize (Zea mays) glu1 gene (Bandaranayake and Esen, 1996, direct submission, GenBank accession no. U44773) and other plant β-glucosidase genes (Xue et al., 1995; Liddle et al., 1996, direct submission, GenBank accession no. X94986). Similarly, primers β-glu69 and A76 were used to amplify the 3′ one-third (627 bp) of the cDNA to serve as the 3′ probe. The 3′ end of the 5′ probe and the 5′ end of the 3′ probe had an overlap of 90 nucleotides. In addition, the 627-bp 3′ probe spans the last three exonic regions interrupted by two introns and the 215-bp-long untranslated region beyond the stop codon.

We have confirmed the presence of these two introns in the dhr1 gene by PCR using primer pairs bracketing them (data not shown). Both fragments (1446 and 627 bp) were used separately in Southern and northern analyses. After PCR, the amplification products were electrophoresed through a low-melting agarose gel (1%), excised, and purified using the Magic PCR Prep system according to the procedure provided by the manufacturer (Promega). The purified PCR products (the 1446- and 627-bp fragments) were labeled with [α-32P]ATP using random hexamers and the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase (Ambion, Austin, TX) at 37°C for 1 h. The labeled fragments were used as a probe in northern- and Southern-blot analyses.

Southern-Blot Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from 3- to 4-d-old seedlings as described by Dellaporta (1994). Approximately 10 μg of DNA was digested with SalI, PvuII, ApaI, XhoI, BamHI, and XbaI for 24 h, loaded onto a 0.8% agarose gel, and fractionated using the Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer system at 1.5 V/cm for 18 h. After electrophoresis, the DNA was transferred overnight to a Nytran membrane (Schleicher & Schuell; Sambrook et al., 1989). DNA was attached to the membrane by UV-cross-linking, and the blots were probed separately with 32P-labeled 5′ (1446 bp)- and 3′ (627 bp)-specific PCR products. The G-C content of both probes was about 49%. The blots were prehybridized in Church buffer (1 mm EDTA, 0.5 m Na2HPO4, pH 7.2, and 7% SDS) at 65°C for 2 h (Church and Gilbert, 1984) and then hybridized with 32P-labeled 5′ probe in 10 mL of Church buffer at 65°C overnight. The blots were washed once in 1× SSC/0.1% SDS at room temperature for 5 min, twice in 1× SSC/0.1% SDS at 65°C for 20 min, and then once in 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS at 65°C. The washed blots were dried and exposed to radiographic film (X-Omat, Kodak) with intensifying screens at −80°C for 24 h. After autoradiography, the 5′ probe was removed from the blot, and the same blot was hybridized with the 3′ probe according to the procedure used for the 5′ probe.

Northern-Blot Analysis

One-half gram of each frozen light- and dark-grown sorghum seedling part was ground in a chilled mortar, and total RNA was extracted as described previously (Chomczynski, 1993). Five micrograms of total RNA from each plant part was heated at 65°C for 15 min, loaded onto a 1% formaldehyde agarose gel, and subjected to electrophoresis at 8 V/cm for 3 h. A Nytran membrane and the gel were soaked in 10× SSC for 10 min. RNA was transferred to the membrane in 10× SSC overnight (Sambrook et al., 1989) and UV-cross-linked to the membrane. RNA was then prehybridized in Church buffer at 65°C for 2 h (Church and Gilbert, 1984) and hybridized with a 32P-labeled, 627-bp 3′ probe according to the procedure described above for Southern blots, except that Church buffer used for hybridizations and washes contained 1% BSA. In addition, a separate northern blot of light-grown seedling parts was hybridized with the 5′ probe and washed at low (1× SSC) and high (0.1× SSC) stringency before autoradiography. This was to investigate whether the dhr2 mRNA could be detected in the leaf and coleoptile in which the 62-kD Dhr2 monomer was detected exclusively on immunoblots.

Extraction of Proteins and Assay of Enzyme Activity

Protein extracts were prepared by grinding the isolated plant parts (coleoptile, node, mesocotyl-2, mesocotyl-1, root-1, and root-2 of dark-grown seedlings and node, coleoptile, leaf, and root of light-grown seedlings) in the extraction buffer as described by Hösel et al. (1987). The homogenate was centrifuged at 18,000g for 20 min, and ice-cold acetone was added to the supernatant to obtain a 35% final concentration. The precipitated material was separated by centrifugation at 18,000g and more ice-cold acetone was added to the resulting supernatants to obtain a 55% final concentration. Following centrifugation at 18,000g for 20 min, the pellet was drained and dissolved in 0.1 volume of water. The purpose of the acetone precipitation was to remove Glc, dhurrin, and its aglycone from protein preparations because they interfered with the PGO assay (see below). The protein content of each extract was determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad).

Total dhurrinase activity, expressed as the amount of dhurrin hydrolyzed (in nanomoles per milligram of protein per hour) was assayed by the PGO-coupled reaction (Raabo and Terkildsen, 1960). Twenty-five-microliter aliquots containing 125 nmol dhurrin in 70% methanol were placed in quadruplicate in the wells of a microtiter plate, evaporated, and tested for hydrolysis by adding 50 μL of an enzyme solution containing 1 μg of protein (35–55% acetone cut) from seedling parts, 50 μL of PGO, and 50 μL of 2,2′-azinobis-3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and the A410 was read in a microplate reader. Under these conditions, the final concentration of dhurrin in the reaction mixture was 0.83 mm, and the rate was linear throughout the 30-min reaction period.

Dhurrin Isolation and Purification

Thirty grams of frozen seedlings was ground in liquid N2, extracted in 70 mL of 100% methanol, and centrifuged at 16,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was freeze-dried and the powder was dissolved in 70% methanol and fractionated on a Sephadex LH-20 gel-filtration column (2.6 × 56 cm) at room temperature (approximately 23–25°C). The fractions were tested for Glc by PGO assay and for dhurrin by the maize β-glucosidase inhibition assay (dhurrin is a potent inhibitor of maize β-glucosidase). The fractions inhibiting maize β-glucosidase were combined, freeze-dried, and rechromatographed on a Sephadex LH-20 column. Each fraction was tested again by PGO and maize β-glucosidase-inhibition assays. The fractions containing dhurrin were combined and used as a substrate in dhurrinase assays as described above.

PAGE and Western-Blot Analysis

The protein extracts of each of the different plant parts were mixed with one-fourth volume of the 4× SDS-gel sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) and heated at 100°C for 5 min. Volumes containing 10 μg of protein from each plant part were loaded onto 12% SDS gels and electrophoresed. After electrophoresis, the gels were soaked in 1× blotting buffer (25 mm Tris/125 mm Gly/0.25% SDS/20% methanol) and the proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore; Pluskal et al., 1986). Immunodetection was carried out using an anti-maize β-glucosidase serum (R681) as described by Mohammed and Esen (1989).

To analyze the two dhurrinase isozymes, Dhr1 and Dhr2, 35 to 55% acetone cuts from a dark-grown node and mesocotyl-2 crude extracts were fractionated under nondenaturing conditions by preparative alkali PAGE. For this, a vertical slice of the slab gel was incubated with 4MUG to determine the position of Dhr2 in the gel. Gel pieces (0.5 cm) were cut starting from the anodic end (bottom) of the gel, eluted in 100 mm phosphate-50 mm citrate buffer, pH 5.8, and analyzed for dhurrinase activity. Eluates were also fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunostained with maize β-glucosidase antisera.

TLC

TLC was performed using 0.25-mm silica-coated plates (PE SIL G/UV, Whatman). Dhr1 and Dhr2 eluates (0.1 unit) from preparative PAGE sections were incubated with a 5 mm final concentration of dhurrin, 4MUG, and pNPG in 20 mm phosphate-10 mm citrate buffer, pH 5.8, for 1 h. Ten microliters of the reaction mixture was spotted on a TLC plate and chromatographed vertically at room temperature for 45 min using an acetonitrile:distilled water (85:15, v/v) mixture as the mobile phase (Robyt and White, 1990). The plate was sprayed with methanol:H2SO4 (4:1, v/v), and then baked at 110°C for 10 min to visualize the hydrolysis products. For each substrate, a no-enzyme control was included in the assay.

RESULTS

Primary Structure of Sorghum β-Glucosidase

When the poly(A+) RNA isolated from 3- to 4-d-old seedlings was used as a template, reverse-transcription PCR with the primer pair β-glu27 (antisense) and the AmpliFINDER anchor (sense) amplified a fragment of 1446 bp corresponding to the 5′ three-fourths of the dhurrinase cDNA. A fragment of this size was expected based on sequences of β-glucosidase cDNAs from maize and other plants. Based on the 5′ end sequence, a 627-bp PCR product corresponding to the 3′ end of the dhurrinase cDNA was amplified as described in Methods. The sequences of the two PCR products (1446 and 627 bp) contained a 90-bp overlap that showed perfect sequence identity. The dhurrinase cDNA was reconstructed by PCR amplification using the extreme 5′ and 3′ end primers (β-glu107 and β-glu108, respectively), and cloning the resulting product into pCR-Script SK(+).

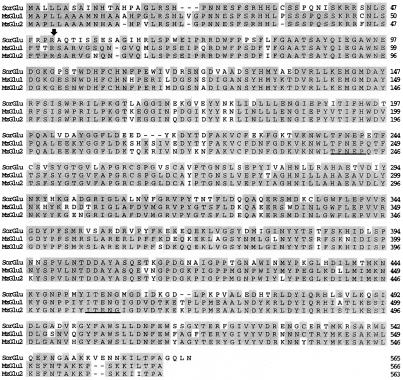

The reconstructed dhurrinase cDNA was 1983 bp long and had a 1695-bp open reading frame coding for a 565-amino acid-long precursor and a 514-amino acid-long mature protein. The precursor had a putative 51-amino acid-long extension (transit peptide) at its N terminus for plastid targeting. The dhurrinase precursor and mature protein sequences showed 70% sequence identity with each of the two (Glu1 and Glu2) maize β-glucosidase precursor and mature proteins (Fig. 2). The 51-amino acid-long dhurrinase transit peptide shared 78% identity with the 51- and 54-amino acid-long transit peptides of the maize β-glucosidase precursors Glu1 and Glu2.

Figure 2.

Deduced amino acid sequence identity between sorghum (SorGlu) and maize (MzGlu1 and MzGlu2) β-glucosidases. The deduced amino acid sequence of sorghum β-glucosidase was aligned with those of maize β-glucosidases using the Clustal multiple-alignment program (Higgins and Sharp, 1989). Sequences boxed in gray indicate regions of amino acid identity between sorghum and maize β-glucosidases. The arrow indicates the known transit peptide cleavage site in maize β-glucosidase precursor proteins and the predicted cleavage site in the sorghum β-glucosidase precursor. The underlined sequences form part of the catalytic site in BGA β-glucosidases.

In addition to amino acid substitutions, the major differences between sorghum and maize β-glucosidases were deletion of three contiguous amino acids (KSI in MzGlu1 and KRI in MzGlu2) in the N-terminal half and two contiguous amino acids (TP in MzGlu1 and KP in MzGlu2) in the C-terminal half. In the C-terminal half, the sorghum protein also had additions of two and four adjacent amino acids (VE and GQLN, respectively; Fig. 2). The two peptide motifs (Fig. 2, underlined sequences) that are known to form part of the catalytic center in BGA β-glucosidases were perfectly conserved in dhurrinase and the two maize β-glucosidases.

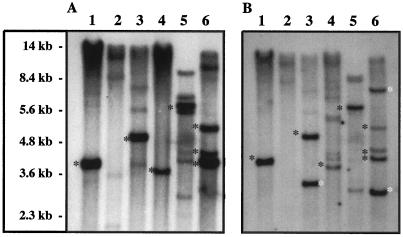

Southern-Blot Analysis

To estimate the number of β-glucosidase genes, Southern-blot analysis of genomic DNA, digested with six different restriction enzymes that do not cut within exons (cDNA), was performed using 32P-labeled 5′ and 3′ probes (1446- and 627-bp fragments, respectively). Our hypothesis is that (a) the sorghum genome has at least two β-glucosidase genes, dhr1 and dhr2, which are homologs of the maize glu1 and glu2, (b) both probes hybridize with all β-glucosidase-related sequences, and (c) strongly hybridizing fragments are derived from the gene that corresponds to the cloned cDNA. This hypothesis is based on the fact that two distinct dhurrinase isozymes from sorghum have been isolated and characterized at the biochemical level and that two isozymes and their corresponding cDNAs and genes have been found in a homologous system (i.e. maize).

In SalI, ApaI, and XhoI digests (Fig. 3A), one strongly hybridizing band (approximately 4.2, 5.3, and 3.8 kb, respectively) was detected when blots were hybridized with the 1446-bp 5′ probe. In contrast, the BamHI and XbaI digests yielded a more complex banding pattern (six to nine bands), each with two to three strongly hybridizing bands (Fig. 3A). In addition, all digests had two to five weak to moderately hybridizing bands the numbers of which varied with the digest (Fig. 3A). The banding profiles produced by the 627-bp 3′ probe indicated that this probe hybridized with some of the same bands as the 1446-bp 5′ probe (Fig. 3), but it also hybridized with novel bands in ApaI and XbaI digests (Fig. 3B). The same novel bands, but with lower signal intensity, were also evident in the XhoI digest (Fig. 3B). As for the PvuII digest, both probes detected two to three moderately hybridizing bands in the 9- to 12-kb region (Fig. 3). In addition, the 5′ probe detected two weakly hybridizing bands in the 2- to 3.6-kb region (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Southern-blot analysis of sorghum genomic DNA after digestion with SalI (1), PvuII (2), ApaI (3), XhoI (4), BamHI (5), and XbaI (6). A, Blot probed with a radiolabeled 1446-bp fragment (corresponding to the 5′ three-fourths of the cDNA). B, Blot in A stripped and then probed with a radiolabeled 627-bp fragment (corresponding to the 3′ one-third of cDNA including the 3′ nontranslated region). Black asterisks indicate the bands that are detected by both probes; white asterisks indicate the novel bands detected by the 3′ region-specific probe only.

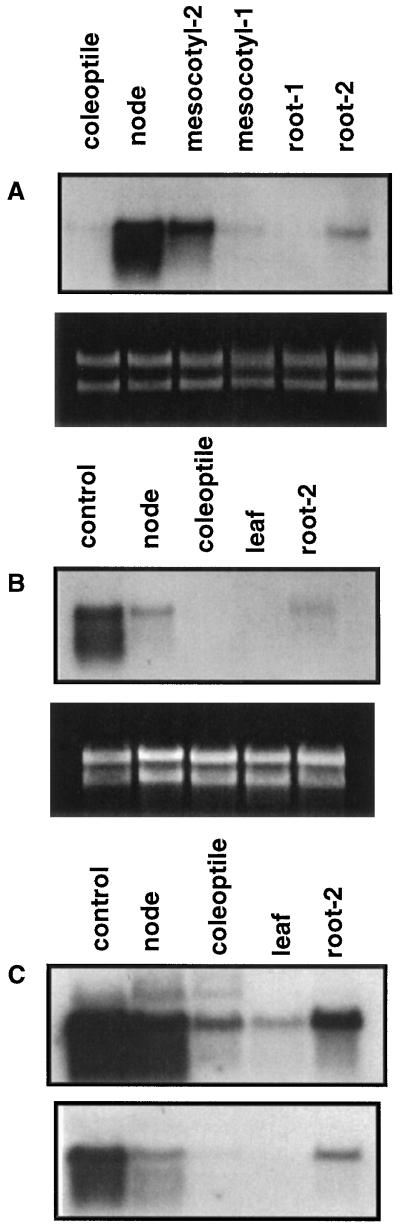

Distribution of β-Glucosidase mRNAs in Different Plant Parts

Northern analysis using the 3′ probe (Fig. 4, A and B) showed that the size of the sorghum β-glucosidase mRNA is about 2 kb, similar in electrophoretic mobility to 18S RNA. This is consistent with the size of the isolated β-glucosidase cDNA (1.983 kb) and suggests that the cDNA is nearly full length. The highest steady-state level of mRNA was detected in the node region (which includes the shoot apex and primordial leaves) of the etiolated seedling, followed by the mesocotyl-2 region (Fig. 4A). The mesocotyl-1 region had the lowest detectable β-glucosidase mRNA in the 2-kb region of the blot (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the coleoptile and the upper half of the primary root (root-1) had little or no detectable mRNA, whereas the lower half of the root (root-2, which includes the root tip) had low levels of mRNA (Fig. 4A). Northern analysis was also performed in light-grown seedling parts (the node, coleoptile, leaves, and root-2; Fig. 4B). Both the node and root-2 regions showed reduced expression compared with that from etiolated seedlings (Fig. 4, compare A and B).

Figure 4.

RNA-blot analysis of dhurrinase expression in various sorghum seedling parts. Ethidium bromide-stained gel below blots shows equal RNA loading before blotting. A, Etiolated seedling parts: coleoptile (including the coleoptile proper and primordial leaves); the node; mesocotyl-2 (adjacent to the node); mesocotyl-1 (adjacent to germ); root-1 (adjacent to germ); and root-2 (root tip). B, Light-grown seedling parts: control, node from dark-grown seedlings; node; coleoptile; leaf; and root-2 (root tip). RNA blots in A and B were hybridized with a 32P-labeled 3′ end (627 bp) cDNA probe. C, Light-grown seedling parts as in B but hybridized with a 32P-labeled 5′ probe (1446 bp) at low (top; 1× SSC) and high (bottom; 0.1× SSC) stringency.

When northern blots of light-grown seedling parts were hybridized with the 5′ probe and washed at low stringency (Fig. 4C), it was possible to detect β-glucosidase transcripts in all seedling parts, including the coleoptile and leaf. In addition, weakly hybridizing RNA bands of >2 kb were detected in etiolated nodes, light-grown nodes, and coleoptiles (Fig. 4C). As expected, substantial signal loss occurred after the high-stringency wash, with loss being essentially complete in coleoptiles and complete in leaves (Fig. 4C).

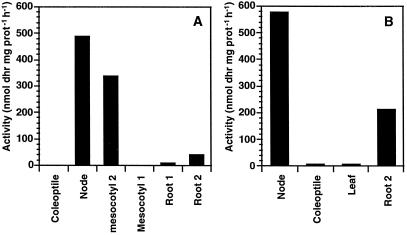

Dhurrinase Activity in Different Plant Parts

The distribution of dhurrinase activity was investigated in dark- and light-grown seedling parts. The results showed that the highest dhurrinase activity was in the node region of both dark- and light-grown seedlings (Fig. 5). Among dark-grown seedling parts, the highest enzyme activity was detected in the node, followed by mesocotyl-2 and root-2, respectively (Fig. 5A). The dhurrinase activity level of the different parts from dark-grown seedlings approximately corresponded to the dhurrinase mRNA levels obtained by northern-blot analysis from the same seedling parts. Similarly, among the light-grown seedling parts, the highest dhurrinase activity was in the node region, followed by the root tip (Fig. 5B). In addition, the root tips from light-grown seedlings had higher dhurrinase activity than those of the dark-grown seedlings. However, in this case, the enzyme activity level was higher than expected from the mRNA levels.

Figure 5.

Specific activity of dhurrinase (expressed as the amount of dhurrin [dhr] hydrolyzed per milligram of protein [prot] per hour) in dark-grown (A) and light-grown (B) sorghum seedling parts.

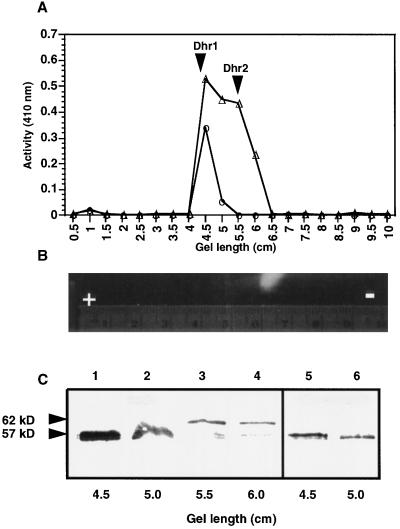

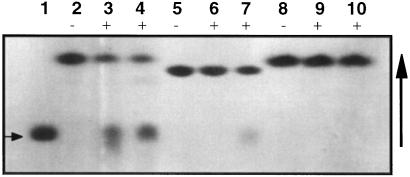

The two β-glucosidase isozymes Dhr1 and Dhr2, isolated by preparative electrophoresis, hydrolyzed the natural substrate dhurrin with similar catalytic efficiencies but showed subtle differences with respect to their ability to hydrolyze the artificial β-glucosides such as pNPG and 4MUG. When the gel eluates were analyzed for dhurrinase activity (Fig. 6A), it was found that the activity was in two distinct zones (4–5 and 5.5–6.5 cm, respectively) in node extracts. Of these, the slower one (Dhr2, 5.5–6.5 cm from the anode) had not only dhurrinase activity but also yielded an activity zone (Fig. 6B) in the gel upon incubation with 4MUG. Hydrolysis of dhurrin and 4MUG by Dhr2 was also confirmed by TLC results (Fig. 7). On the other hand, the zone with faster electrophoretic mobility (Dhr1, 4–4.5 cm from the anode) showed only dhurrinase activity (Fig. 7, lane 3); it had no measurable activity toward 4MUG and pNPG in PGO, gel, and TLC assays (Fig. 7), confirming the results of Hösel et al. (1987). In addition, Dhr1 was the only dhurrinase isoform detected in the mesocotyl portion of the seedling (Fig. 6, A and C).

Figure 6.

Purification of Dhr1 and Dhr2 by native alkaline PAGE and their characterization. A, Hydrolysis of dhurrin by dhurrinase activity present in 5-mm gel slices (numbered 0.5 through 10) cut from a preparative gel starting at the anodic end (▵, node; ○, mesocotyl-2). Note that Dhr1 has a faster mobility than Dhr2 in alkaline gels, is the only dhurrinase isozyme present in the mesocotyl, and is not detected in gels by activity staining with 4MUG, whereas Dhr2 co-occurs with Dhr1 in the node and is detected in gels as a fluorescent zone by staining with 4MUG as evident in B. C, Western analysis of the gel eluates showing dhurrinase activity after electrophoresis through 12% SDS-PAGE, blotting onto PVDF membrane, and immunostaining with maize β-glucosidase antiserum. Lanes 1 to 4, Gel slices from a partially purified node extract; and lanes 5 and 6, slices from a mesocotyl-2 extract.

Figure 7.

Substrate specificity of dhurrinases as assayed by TLC. The physiological substrate dhurrin (lanes 2–4) and artificial substrates 4MUG (lanes 5–7) and pNPG (lanes 8–10) were incubated at a 5 mm final concentration with 0.1 unit of Dhr1 (lanes 3, 6, and 9) and Dhr2 (lanes 4, 7, and 10) purified by preparative gel electrophoresis. Lane 1, Glc (arrow on left); and lanes 2, 5, and 8, no-enzyme controls. Note that both dhurrinase isozymes hydrolyze dhurrin (lanes 3 and 4), whereas only Dhr2 hydrolyzes 4MUG (lane 7). Hydrolysis of pNPG could not be detected after incubation with either enzyme (lanes 9 and 10). +, Incubated with enzyme; −, incubated without enzyme.

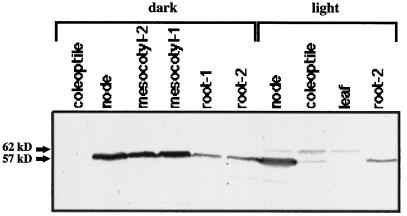

Immunoblotting Analysis

Analysis of the gel-slice eluates after preparative native PAGE of the node extracts revealed two zones of dhurrinase activity. Of these, the zone with faster electrophoretic mobility (4–4.5 cm from the anode) contained a 57-kD immunoreactive band (Fig. 6C), whereas that with slower electrophoretic mobility (6–6.5 cm from the anode) contained a 62-kD immunoreactive band (Fig. 6C). The gel eluates of the mesocotyl region contained only the 57-kD immunoreactive band (Fig. 6C). These results were confirmed when extracts of various seedling parts were analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig. 8). For example, blots of node extracts from both light- and dark-grown seedlings contained two immunoreactive bands (57 and 62 kD), whereas those of the mesocotyl-2, mesocotyl-1, root, and root-tip extracts showed only the 57-kD immunoreactive band (Fig. 8). The 57-kD immunoreactive band was also detectable in mesocotyl-1 and root-1 portions of the dark-grown seedlings (Fig. 8), even though northern analysis and enzyme activity assays were in variance with this result.

Figure 8.

Detection of sorghum β-glucosidase (dhurrinase) isoforms by immunoblotting. Protein extracts from different parts of dark- and light-grown seedlings were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE, blotted onto a PVDF membrane, and immunostained with maize β-glucosidase antiserum. Arrows indicate the relative molecular masses of immunoreactive bands. Note that both dhurrinase isozymes occur in the node and coleoptile regions, whereas Dhr1 is the only isozyme detected in the mesocotyl and the root, and Dhr2 is the only isozyme detected in the leaf. Although the immunoreactive band corresponding to the Dhr2 isozyme was not visible in the node lane, it was present in the original blot, albeit weakly. The presence of Dhr2 in the node is clearly evident in Figure 6C, lanes 3 and 4.

DISCUSSION

Hösel et al. (1987) isolated and characterized two isoforms of the cyanogenic β-glucosidase (i.e. dhurrinase) from sorghum seedlings. Of the two isozymes, dhurrinase-1 was isolated from shoots of the etiolated seedlings and had a monomeric molecular size of 57 kD. The other isozyme, dhurrinase-2, was isolated from the leaves of seedlings grown in the light and had a monomeric molecular size of 62 kD. To our knowledge, no molecular data have been available about the genes encoding either of these two dhurrinase isozymes until the present study. We conclude that the cDNA we cloned and sequenced corresponds to a β-glucosidase and, most likely, to dhurrinase-1 (Dhr1) in sorghum. The cDNA is clearly a β-glucosidase cDNA because its size and that of the mRNA used for reverse transcription-PCR are about 2 kb (Fig. 4), which is similar to those of maize and other plant β-glucosidases that belong to the BGA family (Beguin, 1990).

Furthermore, the deduced mature protein product of the cloned cDNA has a calculated molecular size (58 kD), length (514 amino acids), primary structure (70% sequence identity), and immunological properties similar to those of two maize β-glucosidases Glu1 and Glu2. We think that the cloned cDNA is most likely a dhr1 because the level of mRNA detected with the 3′ probe (a 627-bp fragment derived from the 3′ one-third of the cDNA) in total RNA blots of various seedling parts correlates with the level of dhurrinase activity and the presence of a 57-kD immunoreactive protein in the same seedling parts. Moreover, mRNA was isolated from etiolated seedlings of comparable age to those used for Dhr1 isolation by Hösel et al. (1987). The putative dhr1 cDNA codes for a precursor protein with a 51-amino acid-long N-terminal extension for plastid targeting, again similar in length to those of maize β-glucosidase precursors.

The presence of a putative 51-amino acid-long transit peptide in the dhurrinase precursor supports the results of previous tissue and subcellular localization studies (Kojima et al., 1979; Thayer and Conn, 1981). Kojima et al. (1979) showed that dhurrinase activity was localized in mesophyll (parenchyma) cells of sorghum leaves, whereas dhurrin was localized in the vacuoles of epidermal cells in the leaf. However, Selmar (1996) showed that dhurrin-6′-glucoside (disaccharide-dhurrin) was present in the guttation fluid of sorghum seedlings and was not hydrolyzed by β-glucosidase. Selmar (1996) concluded that dhurrin-6′-glucoside had an apoplastic occurrence as a transport metabolite. Subcellular location of dhurrinase was shown to be in the plastid by Thayer and Conn (1981). The plastid localization of β-glucosidase appears to be common in grasses, because this has been demonstrated in oats (Nisius, 1988), maize (Esen and Stetler, 1993), and rice (C. Muslim and A. Esen, unpublished data).

A putative β-glucosidase precursor from the ginger plant (Costaceae) contains a typical transit peptide for plastid targeting (Inoue et al., 1996), suggesting that plastid localization occurs in other monocot orders. An endosperm-specific β-glucosidase precursor from barley seems to be an exception in that it has a 24-amino acid-long signal peptide for ER targeting (Leah et al., 1995), representing a different β-glucosidase gene lineage. In contrast, there is no report of plastid localization of a β-glucosidase or β-thioglucosidase (i.e. myrosinase) in dicots, nor do their precursors have plastid-targeting transit peptides. The cyanogenic β-glucosidase linamarase was localized to the cell wall in Trifolium repens (Kakes, 1985). Swain and Poulton (1994) also reported that both prunasin hydrolase and mandelonitrile lyase were localized in the vacuoles of phloem parenchyma cells. They also have immunolocalized amygdalin-hydrolase in procambium cells.

Southern analysis data suggest that β-glucosidase is encoded by a small multigene family in sorghum (Fig. 3); this is in agreement with data showing the presence of two immunoreactive polypeptides (57 and 62 kD) on western blots probed with maize β-glucosidase (Glu1) antisera (Figs. 6C and 8). Furthermore, enzymatically active native proteins, one yielding the 57-kD monomer (Dhr1) and the other yielding the 62-kD monomer (Dhr2), were purified by preparative electrophoresis and shown to exhibit the distinct substrate specificities (Fig. 7) reported by Hösel et al. (1987). Thus, the presence of at least two different loci encoding β-glucosidase in the sorghum genome is expected. It is likely that the strongly hybridizing bands detected by the 5′ and 3′ probes indicate perfect complementarity between target and probe sequences and thus correspond to the cloned cDNA (most probably dhr1), whereas the weakly hybridizing bands corresponded to dhr2 or other β-glucosidase-related sequences.

The detection of novel bands in blots of ApaI and XbaI digests (Fig. 3B) probed with the 627-bp fragment (3′ region specific) suggests that one of the last two introns of the dhr1 gene has an ApaI and an XbaI site or that one has an ApaI site and the other has an XbaI site (or vice versa). In this case, the 3′ probe, having been derived from exons flanking these introns, would detect both fragments from a cleavage within one of the two introns, whereas the 5′ probe detected only the fragment upstream of the cleavage site. As for the multiple bands varying in size from 4 to 10 kb, which hybridized with both 5′ (1446 bp) and 3′ (627 bp) region-specific probes in blots of XbaI and BamHI digests, the most plausible explanation is incomplete digestion of genomic DNA by XbaI and BamHI due to cytosine methylation. Both enzymes are inhibited when the residues in their cleavage site (marked with an asterisk) are methylated (e.g. T/C*TAGA* for XbaI and G/GATC*C for BamHI). Likewise, the absence of any strongly hybridizing bands in PvuII digests (Fig. 3) can be explained by poor digestion, since this enzyme is also methylation sensitive.

Northern analysis results indicated both qualitative and quantitative differences in the organ-specific expression of β-glucosidase genes in sorghum. In view of stringent conditions and the 3′ region probe used for hybridization, it is very likely that our northern analysis detected the cDNA-related transcripts, which we hypothesize are from dhr1. It was apparent that the highest level of β-glucosidase mRNA was in the node region of the etiolated seedlings, followed by the mesocotyl-2 and the zone of elongation in the root (Fig. 4A). The detection of β-glucosidase mRNA in leaf and coleoptile blots after hybridization with the 5′ probe and a low-stringency wash (Fig. 4C) but not after a high-stringency wash, especially in the leaf lane (Fig. 4C) could be due to the fact that the transcript corresponds to the dhr2 gene, and thus the dhr1 and dhr2 genes show spatial expression differences. Although this hypothesis is supported by detection of the 62-kD Dhr2 monomer only in immunoblots of the leaf and coleoptile extracts (Fig. 8), it is also possible that at low stringency the increased signal enables the detection of low amounts of dhr1 in these tissues and that this probe cannot recognize dhr2.

The nature of weakly hybridizing, larger RNA bands detected in the node and coleoptile lanes (Fig. 4C) with the 5′ probe after low-stringency washes is not known. It is conceivable that they are partially spliced β-glucosidase precursor mRNAs or transcripts of other genes that share partial similarity with β-glucosidase genes.

The detection of trace amounts of the 62-kD monomer in the node and the 57-kD monomer in the coleoptile extracts may be due to the difficulty involved in separating these seedling parts cleanly from each other (Fig. 8). Similarly, the fact that there is still a detectable level of signal (the dhr1 transcript?) in the coleoptile blot after a high-stringency wash (Fig. 4C) may be due to contamination from the upper portion of the node with leaf and coleoptile during the excision of individual seedling parts. The maize β-glucosidase gene glu1 was shown to exhibit organ-specific expression by northern analysis (Brzobohaty et al., 1993) in that the largest amount of the transcript was in the root and mesocotyl sections. However, these results could not be confirmed by recent studies in our laboratory (H. Bandaranayake and A. Esen, unpublished data), showing that the glu1 message was most abundant in the node and mesocotyl-2.

Although the distribution of β-glucosidase in various organs of maize seedlings does not seem to coincide well with that of sorghum in the node, mesocotyl, and root, the discrepancy may be due to the differences in the physiological and chronological age of the materials and the way seedlings were divided into different parts. Since maize and sorghum β-glucosidase amino acid sequences show 70% sequence identity, and both taxa are members of the same tribe (Andropogonea) in the subfamily Panicoideae, one would not expect substantial temporal and spatial expression differences between their homologous genes.

β-Glucosidase expression in dark- and light-grown sorghum seedling parts was also studied by western analysis using anti-maize β-glucosidase sera. This was made possible because sorghum and maize β-glucosidases showed immunological cross-reactivity, which is not surprising in view of their high sequence similarity. The antibodies reacted specifically with two polypeptides of 57 and 62 kD (Figs. 6C and 8), which show organ-specific expression. Particularly, the node section of the etiolated seedling, which contains mitotically active tissues (shoot apex and primordial leaves), also has the highest level of dhurrinase mRNA and protein (Figs. 4 and 6). These results were confirmed by northern analysis using RNA isolated from light-grown seedling parts.

The fact that we found the second-highest dhurrinase activity in the root-tip region of light-grown seedlings (Fig. 5B) and isolated only Dhr1 from this plant part but detected a very low level of dhurrinase mRNA in northern blots (Fig. 4B) can be explained by the rapid turnover of the mRNA and the accumulation of the Dhr1 protein over time during seedling growth. The presence of a 57-kD immunoreactive band of similar intensity in blots of the root-1 and root-2 region extracts from dark-grown seedlings (Fig. 8) but only about 25% of the expected activity in the root-1 region 30 to 50% acetone cut (Fig. 5A) was very likely due to inefficient precipitation of the enzyme. The root-1 region extracts had the lowest amount of protein on a fresh-weight basis among all plant parts, and precipitability of proteins by acetone decreases as protein concentration of the starting extract decreases.

The presence of Dhr2 in the node region of etiolated seedlings was confirmed by both zymogram and immunoblotting assays, as well as by purification and characterization by preparative gel electrophoresis. Therefore, these data unequivocally establish the presence of Dhr2 not only in the green leaves (Hösel et al., 1987) and node but also in etiolated seedlings. Since the node includes the shoot apex and primordial leaves, it is likely that Dhr2 found in the node comes from primordial leaves. However, precise localization of the two isozymes and their transcripts with respect to specific tissues and organs needs to be performed by immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization, which will be the subject of future studies.

In conclusion, the cDNA we cloned and sequenced using mRNA from seedlings of the same age as those used by Hösel et al. (1987) codes for a β-glucosidase. Its putative protein product has both high sequence identity and immunological cross-reactivity with maize β-glucosidases. Its abundant expression in the node and root portions of the 3- to 4-d-old etiolated seedlings and its size (57 kD) indicate that what we refer to here as dhurrinase-1 (Dhr1) is identical to what was isolated and named dhurrinase-1 by Hösel et al. (1987). Western analysis data indicate the existence of at least one other β-glucosidase enzyme in sorghum, which may be encoded by a different gene, very likely dhr2. The expression of the two dhurrinase proteins differs spatially and temporally (results not shown), making them an interesting model for the study of gene regulation.

Abbreviations:

- BGA

β-glucosidase family A

- DEPC

diethylpyrocarbonate

- 4MUG

4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-Glc

- PGO

peroxidase-Glc-oxidase

- pNPG

p-nitrophenyl-β-d-Glc

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by grant no. IBN-9318134 from the National Science Foundation.

LITERATURE CITED

- Babcock GW, Esen A. Substrate specificity of maize β-glucosidase. Plant Sci. 1994;101:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bandaranayake H, Esen A. Nucleotide sequence of a β-glucosidase (glu2) cDNA from maize (Zea mays L.) (accession no. U44087) (PGR 96-009) Plant Physiol. 1996;110:1048. [Google Scholar]

- Beguin P. Molecular biology of cellulose degradation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:219–248. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler E. Gaucher disease: new molecular approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Science. 1992;256:794–798. doi: 10.1126/science.1589760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzobohaty B, Moore I, Kristoffersen P, Bako L, Campos N, Schell J, Palme K. Release of active cytokinin by a β-glucosidase localized to the maize root meristem. Science. 1993;262:1051–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.8235622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P. A reagent for the single-step simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA and proteins from cell and tissue samples. Biotechniques. 1993;15:532–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn EE (1981) Cyanogenic glycosides. In PK Stumpf, E Conn, eds, The Biochemistry of Plants: A Comprehensive Treatise, Vol 7: Secondary Plant Products. Academic Press, New York, pp 479–500

- Cuevas L, Niemeyer HM, Jonsson LMV. Partial purification and characterization of a hydroxamic acid glucoside β-glucosidase from maize. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:2609–2619. [Google Scholar]

- Dellaporta S. Plant DNA miniprep and microprep. In: Freeling F, Walbot V, editors. The Maize Hand Book. Inc., New York: Springer-Verlag; 1994. pp. 522–525. [Google Scholar]

- Esen A, Stetler DA. Subcellular localization of maize β-glucosidase. Maize Genet Coop News Lett. 1993;67:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gussow D, Clackson T. Direct clone characterization from plaques and colonies by the polymerase chain reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4000. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.10.4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DG, Sharp PM. Fast and sensitive multiple sequence alignments on a microcomputer. Comput Appl Biosci Commun. 1989;5:151–153. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hösel W, Conn EE. The aglycone specificity of plant β-glycosidases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1982;7:219–221. [Google Scholar]

- Hösel W, Tober I, Eklund SH, Conn EE. Characterization of β-glucosidase with high specificity for the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor(L.) Moench seedlings. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;252:152–162. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska AJ. Cyanogenic glucosides as defense compounds. A review of the evidence. J Chem Ecol. 1988;14:2213–2217. doi: 10.1007/BF01014026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MA, Dunn MA. Biochemical characterization of the Li locus, which controls the activity of the cyanogenic β-glucosidase in Trifolium repensL. Plant Mol Biol. 1982;1:169–181. doi: 10.1007/BF00021030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Shibuya M, Yamamoto K, Ebizuka Y. Molecular cloning and bacterial expression of a cDNA encoding furostanol glycoside 26-O-beta-glucosidase of Costus speciosus. FEBS Lett. 1996;389:273–277. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen KS, Breivold E, Hornes E. Purification of mRNA directly from crude plant tissues in 15 minutes using magnetic oligo dT microspheres. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3669. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakes P. Linamarase and other β-glucosidases are present in the cell walls of Trifolium repensL. leaves. Planta. 1985;166:156–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00397342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M, Poulton JE, Thayer SS, Conn EE. Tissue distributions of dhurrin and of enzymes involved in its metabolism in leaves of Sorghum bicolor. Plant Physiol. 1979;63:1022–1028. doi: 10.1104/pp.63.6.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;277:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leah R, Kigel J, Svendsen I, Mundy J. Biochemical and molecular characterization of a barley seed β-glucosidase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15789–15797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed K, Esen A. A blocking agent and a blocking step are not needed in ELISA, immunostaining dot-blots and western blots. J Immunol Method. 1989;117:141–145. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer HM. Hydroxamic acid (4-hydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-ones) defense chemicals in the Gramineae. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:3349–3358. [Google Scholar]

- Nisius A. The stromacentre in Avena plastids:an aggregation of β-glucosidase responsible for the activation of oat-leaf saponins. Planta. 1988;173:474–481. doi: 10.1007/BF00958960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluskal MG, Przekop MB, Kavonian MR, Vecoli C, Hicks DA. ImmobilonTM PVDF transfer membrane:a new membrane substrate for western blotting of proteins. Biotechniques. 1986;4:272–282. [Google Scholar]

- Poulton JE (1989) Toxic compounds in plant foodstuffs: cyanogens. In JE Kinsella, WG Soucie, eds, Food Proteins. The American Oil Chemists' Society, Champaign, IL, pp 381–401

- Poulton JE. Cyanogenesis in plants. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:401–405. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulton JE. Enzymology of cyanogenesis in rosaceous stone fruits. In: Esen A, editor. β-Glucosidases: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, ACS symposium series 533. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1993. pp. 170–190. [Google Scholar]

- Raabo E, Terkildsen TC. On the enzymatic determination of blood glucose. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1960;12:402. doi: 10.3109/00365516009065404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese ET. Degradation of polymeric carbohydrates by microbial enzymes. Rec Adv Phytochem. 1977;11:311–364. [Google Scholar]

- Robyt FJ, White BJ (1990) Biochemical Techniques, Theory and Practice, Chapter 4. Waveland Press, Inc., Lake Zurich, IL, pp 107–108

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Selmar D. Apoplastic occurrence of cyanogenic β-glucosidases and consequences for the metabolism of cyanogenic glucosides. In: Esen A, editor. β-Glucosidases: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, ACS symposium series 533. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1993. pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Selmar D. Dhurrin-6′-glucoside, a cyanogenic diglucoside from Sorghum bicolor. Phytochemistry. 1996;43:569–572. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(96)00297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmar D, Lieberei R, Biehl B, Voigh J. Hevealinamarase, a nonspecific β-glycosidase. Plant Physiol. 1987;83:557–562. doi: 10.1104/pp.83.3.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain E, Poulton JE. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1285–1291. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer SS, Conn EE. Subcellular localization of dhurrin β-glucosidases and hydroxynitrile lyase in the mesophyll cells of sorghum leaf blades. Plant Physiol. 1981;67:617–622. doi: 10.1104/pp.67.4.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward J, Wiseman A. Fungal and other β-d-glucosidases. Their properties and applications. Enzyme Microbiol Technol. 1982;4:73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Xue J, Jorgensen M, Pihlgren U, Rask L. The myrosinase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana:gene organization, expression and evolution. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:911–922. doi: 10.1007/BF00037019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]