Abstract

Objectives

To describe patient demographics, interventions, and outcomes in hospitalized children with macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) complicating systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, Oct 1, 2006 to September 30, 2010. Participants had ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for MAS and either SLE or JIA. The primary outcome was hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included intensive care unit (ICU) admission, critical care interventions, and medication use.

Results

121 children at 28 children’s hospitals met inclusion criteria, including 19 with SLE and 102 with JIA. Index admission mortality was 7% (8/121). ICU admission (33%), mechanical ventilation (26%), and inotrope/vasopressor therapy (26%) were common. Compared to children with JIA, those with SLE had similar mortality (6% versus 11%, exact p = 0.6), more ICU care (63% versus 27%, p = 0.002), more mechanical ventilation (53% versus 21%, p = 0.003), and more cardiovascular dysfunction (inotrope/vasopressor 47% versus 23%, p = 0.02). Children with SLE and JIA received cyclosporine at similar rates, but more children with SLE received cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil and more children with JIA received interleukin-1 antagonists.

Conclusions

Organ system dysfunction is common in children with rheumatic diseases complicated by MAS, and children with underlying SLE require more organ system support than children with JIA. Current treatment of pediatric MAS varies based on the underlying rheumatic disease.

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) are incompletely understood conditions associated with uncontrolled and ineffective immune activation.1 Both conditions have high mortality rates, particularly when untreated.1–4 HLH encompasses two related conditions, a primary form in genetically predisposed patients typically diagnosed in infancy or early childhood, and a secondary form that may develop in response to an inflammatory stimulus such as infection (often viral)1, malignancy5 or rheumatic disease.2 MAS is a known complication of pediatric rheumatic disorders, particularly juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)3 and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).6,7 It has been suggested that MAS is the same disorder as the secondary or “reactive” form of HLH.8

Diagnostic and treatment approaches for children with HLH are generally based on HLH-04, a recently updated study protocol that includes initial treatment with dexamethasone, cyclosporine, and etoposide for both primary and secondary forms.2 Alternatively, children with MAS and a known rheumatic disease may receive varying regimens including high dose methylprednisolone, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), azathioprine, rituximab, or interleukin-1 antagonists.7,9 These immunosuppressive medications are typically chosen because they have activity against both the underlying rheumatic disease and MAS. Children with HLH or MAS often require hospital or intensive care unit (ICU) management for organ system dysfunction or for secondary infections related to immunosuppression.2,3 Recent reports of MAS complicating SLE have prompted concern that this association may be under-recognized.6,7

Pediatric rheumatic diseases are rare, and MAS is not a frequent complication. As such, large collaborations have been required to collect data on cohorts of children with MAS and rheumatic diseases.3,7 The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database has unique advantages for researchers studying hospitalized children with rare diseases and recently was used for studies of Kawasaki Disease (KD)10 and Henoch-Schoenlein Purpura.11,12

The purpose of this study was to describe subject demographics, therapeutic interventions, and outcomes in a cohort of children with SLE and JIA complicated by MAS, and to evaluate variation in treatment, costs, and outcomes across these disease groups.

Patients and methods

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of the PHIS database developed by the Children’s Hospital Association13 (formerly known as the Child Health Corporation of America) (Shawnee Mission, KS). The subjects were children who received inpatient care for MAS and SLE or JIA at a PHIS hospital.

Setting

The Children’s Hospital Association is a business alliance of 43 children’s hospitals, and PHIS contains administrative data including patient demographics, diagnoses, procedures, and charges. In addition, a subset of PHIS hospitals submits “Level II” data - detailed data for billed services including pharmacy, clinical services, imaging, laboratory, supply, and room charges.11 Clinical Transaction Classification™ (CTC) codes are used to identify the detailed billing services received by patients.11,14,15 All PHIS data are de-identified and checked for reliability and validity prior to release.14 We obtained data regarding patients admitted to PHIS member hospitals who met our inclusion criteria. Our data use agreement limits reporting of hospital-level data, but general information on 36 PHIS hospitals has been published previously11, and several studies of uncommon diseases in children admitted to PHIS hospitals have been published.10,11,16,17

Selection of Participants

We identified children treated at a PHIS hospital with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) discharge diagnosis codes for MAS (288.4, Hemophagocytic syndromes) and one of SLE (710.0) or JIA (714.30–714.33) from October 1, 2006 to September 30, 2010. We grouped all categories of JIA together because misclassification of the type of JIA in administrative data was more likely than MAS in a child with a category of JIA other than systemic arthritis.

The 288.4 diagnosis code for Hemophagocytic syndromes was adopted on October 1, 200618, replacing the more generic code 288.0 (Leukopenia), which had previously been used for patients with MAS. We defined the index admission as the first admission that met inclusion criteria for each individual patient.

Covariates and Outcomes

Unless otherwise noted, all analyses were of each patient’s index admission. The ICD-9-CM procedure and diagnosis codes used to identify diagnostic and therapeutic interventions and complications are available upon request. The primary outcome was hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes and covariates included ICU admission, length of stay, hospitalization costs, critical care interventions, central nervous system (CNS) evaluations and therapies, gastrointestinal hemorrhage and blood product transfusions, and immunosuppressive medication use. All medication use was ascertained using pharmacy CTC codes, and each drug had an associated “day of service” code indicating the hospital day on which that drug was ordered. The inotrope/vasopressor variable included any use of dopamine, dobutamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, or phenylephrine. The antiepileptic variable included any use of phenobarbital, phenytoin, fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, or valproic acid. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was coded using both CTC and ICD-9-CM codes. Other blood products were coded using ICD-9-CM procedure codes. Adjusted total inpatient costs were calculated by PHIS from charges using hospital-specific ratios of costs-to-charges, and are adjusted by the Center for Medicare wage index.14

Primary Data Analyses

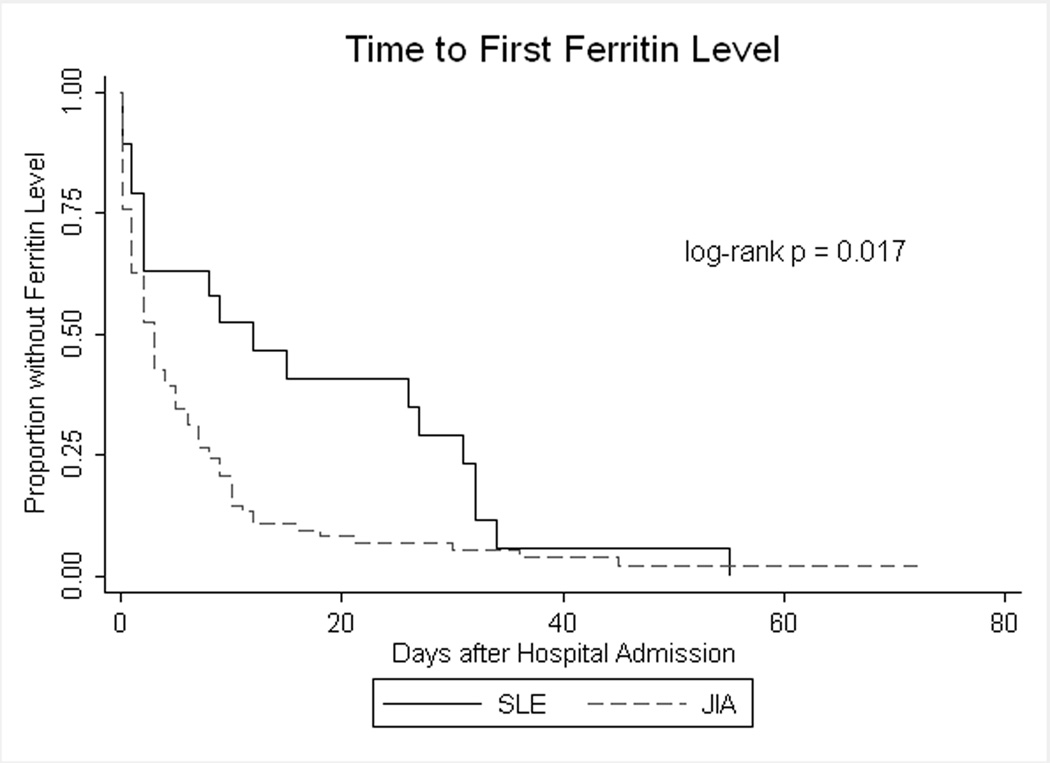

We compared categorical covariates and outcomes using the chi-square test or Pearson’s exact test where appropriate, and length of stay (LOS) and costs using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. We used Kaplan-Meier analysis to estimate the distribution of time (in days after admission) to the first usage of cyclosporine and the first ferritin level test, and the log-rank test to test for differences by diagnosis type. A ferritin level is a component of the diagnostic guidelines for HLH2, which may be applied to children with rheumatic diseases being evaluated for MAS.7

Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, and all analyses were performed using STATA™, version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). This study was reviewed and informed consent was not required by the University of Utah School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Patient Selection Criteria Validation

We validated our patient selection criteria by reviewing the electronic medical record of patients who met our inclusion criteria at a single PHIS hospital to confirm the provider diagnosis of SLE or JIA and MAS.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Subjects

We identified 7,436 inpatient admissions at PHIS hospitals by 3,567 unique patients with diagnoses of SLE or JIA, and 1,379 admissions by 628 patients with a diagnosis code for MAS. Of those, 198 admissions by 123 unique patients had both a diagnosis of SLE or JIA and a diagnosis code for MAS. Subsequent admissions were then excluded, and two patients were excluded for missing disposition at the index admission, leaving N = 121. A median of 4 patients (range 1–18, interquartile range [IQR] 2–5) per hospital were treated at 28 hospitals over 48 calendar months. Each of the 28 hospitals listed at least one staff pediatric rheumatologist on their publicly available website on June 21, 2012.

In this cohort of children with their first admission for MAS, JIA was much more common than SLE (Table 1). Of the children with JIA, 88% (90/102) had an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for systemic JIA (714.30), 8% (8/102) polyarticular JIA (714.31), 3% (3/102) pauciarticular JIA (714.32), and 1% (1/102) monoarticular JIA (714.33). Two children had diagnoses for both JIA and KD at the index admission. No patients were coded for both SLE and JIA.

Table 1.

Patient and admission characteristics of pediatric MAS cohort, by diagnosis type

| SLEa, n(colb %) | JIAc, n(col%) | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 19 | N = 102 | |

| Age | ||

| 0 to 364 days | 1(5) | 1(1) |

| 1 to <5 years | 0(0) | 31(30) |

| 5 to <13 years | 2(11) | 37(36) |

| 13 to <18 years | 16(84) | 33(32) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 12(63) | 65(64) |

| Male | 7(37) | 37(36) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White/Non-Hispanic | 4(21) | 51(50) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6(32) | 16(16) |

| Black | 1(5) | 17(17) |

| Other | 8(42) | 16(16) |

| Missing | 0(0) | 2(2) |

| Insurance status | ||

| Government | 8(42) | 41(40) |

| Private | 6(32) | 43(42) |

| Other | 5(26) | 15(15) |

| Missing | 0(0) | 3(3) |

| Admission year | ||

| 2006–2007 | 3(16) | 36(35) |

| 2008 | 4(21) | 27(26) |

| 2009 | 10(53) | 16(16) |

| 2010 | 2(11) | 23(23) |

| Mortality, n(%) | 2(11) | 6(6) |

| ICUd days | ||

| Any - n(%) | 12(63) | 28(27) |

| Min–Max | 0–155 | 0–77 |

| Med (IQRe) | 8(0–13) | 0(0–1) |

| Length of stay (days) | ||

| Min–Max | 6–367 | 1–122 |

| Med (IQR) | 25(12–80) | 6(4–15) |

| Adjusted total costs | ||

| Min–Max (x$1000) | 9.7–2230.3 | 1.8–674.2 |

| Med (IQR) (x$1000) | 126.7(28.2–359.7) | 16.9(8.4–41.9) |

| Missing, n(%) | 0(0) | 9(9) |

| HSCTf, n(%) | 0(0) | 2(2) |

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Column percentages

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Intensive Care Unit

Interquartile Range

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant

Children with JIA were more likely to be younger than five years old than children with SLE (Table 1). In the entire cohort, nearly two-thirds (64%) of the patients were female, non-white race/ethnicity (54%) was more common than white race/ethnicity (46%) and approximately 18% of patients were of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Hospital mortality was 7% (Table 1). Children with JIA had similar mortality (6% versus 11%, exact p = 0.6) compared to children with SLE.

Intensive care unit admission (33%) was common. The median hospital LOS was 8 days (IQR 5–19 days), and the median hospital cost was $21,574 (IQR $9,501–59,781). Children with SLE had a higher ICU admission rate (63% versus 27%, p = 0.002), longer LOS (median 25 days versus 6 days, p < 0.001), and higher costs (median $126,600 versus $16,886, p < 0.001) than children with JIA.

Mechanical ventilation (26%) and inotrope/vasopressor therapy (26%) were common (Table 2). Children with SLE received more mechanical ventilation (53% versus 21%, p = 0.003) and more cardiovascular support (inotrope/vasopressor 47% versus 23%, p = 0.02) than children with JIA. Three patients with JIA received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) to support vital organ failure, and only one survived.

Table 2.

Selected diagnoses and interventions in pediatric MAS cohort, by diagnosis type

| SLEa, n(%) | JIAb, n(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 19 | N = 102 | |

| Critical Care | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | 10(53) | 21(21) |

| Nitric Oxide | 0(0) | 6(6) |

| Dialysis or CRRTd | 5(26) | 6(6) |

| Inotrope/Vasopressor | 9(47) | 23(23) |

| ECMOe | 0(0) | 3(3) |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) | ||

| Ischemic Stroke | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Intracranial Hemorrhage | 2(11) | 1(1) |

| Hypertonic Saline | 7(37) | 7(7) |

| Mannitol | 2(11) | 0(0) |

| Antiepileptic | 5(26) | 7(7) |

| CNS Diagnostics | ||

| ICPf monitor | 1(5) | 2(2) |

| Brain CTg | 9(47) | 7(7) |

| Brain MRIh and/or MRAi | 9(47) | 7(7) |

| Any CNS Imaging | 12(63) | 13(13) |

| EEGj | 5(26) | 6(6) |

| CNS Imaging or EEG | 12(63) | 14(13) |

| Electrolyte Disorder | ||

| Hyponatremia | 5(26) | 4(4) |

| Bleeding/Transfusion | ||

| PRBCk | 7(37) | 14(14) |

| Platelets | 3(16) | 5(5) |

| Plasma | 3(16) | 7(7) |

| Activated Factor VIIa | 1(5) | 1(1) |

| GIm Hemorrhage | 3(16) | 0(0) |

| Bone Marrow Biopsy | 6(32) | 39(38) |

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Juvenile Inflammatory Arthritis

Kawasaki Disease

Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

Intracranial Pressure

Computed Tomography

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic Resonance Angiogram

Electroencephalogram

Packed Red Blood Cell

Intravenous Immunoglobulin

Gastrointestinal

We defined concern for CNS involvement as receipt of a brain magnetic resonance or computed tomography scan or an electroencephalogram (EEG). Overall, 21% of subjects received CNS imaging or an EEG, with higher rates among patients with SLE (63%) than JIA (14%, p < 0.001) (Table 2). Concern for CNS involvement as evidenced by CNS imaging or EEG was associated with hospital mortality: 27% (7/26) of those with CNS imaging or an EEG died versus 1% (1/95) without, exact p < 0.001).

Hyponatremia occurred in 7% of patients, with higher rates among children with SLE than children with JIA (26% versus 4%, exact p = 0.005, Table 2). Hypertonic saline (any concentration greater than 0.9%) administration was fairly common (12%), again with greater use in children with SLE than JIA (37% versus 7%, p < 0.001, Table 2). However, most children who received hypertonic saline (10/14, 71%) did not have a diagnosis code for hyponatremia. Only 2 children (both with SLE) received mannitol, and only 3 children (1 with SLE and 2 with JIA) received ICP monitoring.

Blood product transfusion (packed red blood cells, platelets, or plasma) was common (20% of all patients), with higher rates among children with SLE than children with JIA (42% versus 16%, p = 0.008, Table 2).

Immunosuppressive Treatments

The use of immunosuppressive medications by diagnosis category is shown in Table 3. Most patients (93%) received corticosteroids, most often methylprednisolone (83%). More children with SLE compared to those with JIA (32% versus 14%, p = 0.05) received dexamethasone, the corticosteroid recommended in the HLH-04 protocol. Children with SLE were more likely to receive cyclophosphamide (21% versus 3%, exact p = 0.01) and MMF (32% versus 2%, exact p < 0.001) than children with JIA.

Table 3.

Immunosuppressive medications received by pediatric MAS cohort, by diagnosis type

| SLEa, n(%) | JIAb, n(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 19 | N = 102 | |

| Drug or Combination, n(%) | ||

| Any steroid | 19(100) | 93(91) |

| Dexamethasone | 6(32) | 14(14) |

| Methylprednisolone | 17(89) | 83(81) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 4(21) | 3(3) |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | 6(32) | 2(2) |

| Azathioprine | 1(5) | 0(0) |

| IL-1d blockade | 0(0) | 15(15) |

| Rituximab | 2(1) | 1(1) |

| ITe hydrocortisone | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| IT methotrexate | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| IVf Immunoglobulin (IVIG) | 7(37) | 18(18) |

| Plasmapheresis | 2(11) | 0(0) |

| Neither CsAg nor Etoposide | 9(47) | 55(54) |

| Etoposide alone | 1(5) | 2(2) |

| CsA alone | 8(42) | 43(42) |

| CsA and etoposide | 1(5) | 2(2) |

| Estimated % given drug (95% CI) | ||

| CsA | ||

| Days after admission | ||

| 3 | 21 (8–47) | 33 (25–43) |

| 7 | 26 (12–52) | 43 (33–54) |

| 14 | 40 (21–66) | 51 (39–64) |

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Juvenile Inflammatory Arthritis

Kawasaki Disease

Interleukin-1

Intrathecal

Intravenous

Cyclosporine A

Fifteen patients at 8 hospitals, all with underlying JIA, received an Interleukin-1 (IL-1) antagonist. Of these 15 patients, 14 also received corticosteroids, 5 received cyclosporine, and 1 received etoposide. IL-1 antagonists tended to be given early in the admission: 11/15 received the IL-1 antagonist by hospital day 3, and 13/15 by hospital day 6.

The proportions of children with SLE and JIA receiving IVIG did not differ significantly (37% versus 18%, exact p = 0.06), and plasmapheresis was infrequently used (two patients, both with SLE) (Table 3).

Approximately half (47%) of all patients received either cyclosporine or etoposide, with most of those (42%) receiving cyclosporine alone and only 2% etoposide alone and 2% both cyclosporine and etoposide. Equivalent proportions (47% versus 44%, p = 0.8) of children with SLE and JIA received cyclosporine. We did not find a difference between children with SLE and those with JIA in the number of days after admission when the first dose of cyclosporine was given (log-rank p = 0.196).

Two patients with JIA received a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) at the index hospital during the index admission.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of patients who received corticosteroids, IVIG cyclosporine, etoposide, and IL-1 antagonists in each year of the study. Other than a modest decrease in corticosteroid use over time, there do not appear to be consistent trends in immunosuppressant use over time.

Figure 1.

Immunosuppressive therapies used in pediatric MAS cohort, by admission year

Laboratory Testing

Overall, 92% (111/121) of patients had a ferritin level checked during the hospitalization, with no difference between children with SLE (18/19, 95%) and JIA (93/102, 91%), exact p = 1.00. Figure 2 shows the time, in days after hospital admission, to the first ferritin level. Children with JIA had a ferritin level checked earlier in the hospitalization than children with SLE (log-rank p = 0.017). After one week of hospitalization, we estimate that 37% (95% confidence interval [CI] 20–62%) of children with SLE and 73% (95% CI 64–82%) of children with JIA had a ferritin level checked.

Figure 2.

Time to first ferritin level in pediatric MAS cohort

Patient Selection Criteria Validation

We identified all patients (5) at one PHIS hospital using our selection criteria, and confirmed that the medical record reported diagnoses of SLE or JIA and MAS in 5/5.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this multi-center study is the largest reported cohort of hospitalized children with MAS complicating a chronic rheumatic disease. ICU admission and organ system dysfunction were common in children with SLE and JIA, and children with underlying SLE required more organ system support than those with JIA. As expected given typical treatments for the two underlying rheumatic diseases, children with SLE and JIA complicated by MAS received cyclosporine at similar rates, but more children with SLE received cyclophosphamide and MMF and more children with JIA received IL-1 antagonists.

More hospitalized children with MAS in our study had JIA than SLE. This is consistent with previous reports that MAS may be more common in children with JIA than children with SLE.3 Other investigators have suggested that MAS is not recognized as readily in children with SLE compared to children with other rheumatic disorders.6 Our finding that children with JIA had a ferritin level checked earlier in the hospital admission than children with SLE lends support to the concern about delayed diagnosis of MAS in children with SLE and to recent efforts to develop diagnostic criteria for MAS in children with SLE.7

The index admission mortality of 7% in our cohort is similar to reported mortality rates of 7–22% from case series that included readmission data.3,4,7,19 The age and gender distributions in our dataset fit with what is known about the epidemiology of SLE7 and JIA3. The ICU admission rate in our study was 33% overall (compared to 42% reported3) with a higher rate (63%) in children with SLE (consistent with 57% reported7).

We found that children with SLE have more organ system dysfunction, longer hospital stays, and higher costs at their index hospitalization for MAS than children with JIA. Other investigators have presented the hypothesis that children with SLE and MAS have more organ system dysfunction6, which a recent registry study would also support.7 Ours is the first study to compare children with SLE and JIA in a large cohort, and the first analysis to report medication, imaging, laboratory, and cost data.

Our estimate of CNS involvement during the index admission (21%), identified by utilization of CNS imaging or EEG, was within the wide range reported in other studies (14–67%, with variable case definitions).3,7,19,20 Presumably the imaging studies and EEG’s were obtained in patients who had altered mental status, clinical seizures, or other manifestations of CNS disease. We found higher CNS involvement rates among children with SLE than those with JIA, as might be expected given the potential for CNS involvement in SLE without MAS. Index admission mortality was high (27%, compared to 1% without CNS disease) among the patients with CNS involvement in our study. CNS events, including intracranial hemorrhages and cerebral edema, may be important contributors to morbidity and mortality in children with MAS. The higher dexamethasone use we found in children with SLE compared to those with JIA may reflect providers’ decisions to administer a corticosteroid with better CNS penetration than methylprednisolone.

Hyponatremia is known to complicate active disease in children with rheumatic diseases and MAS.20,21 We found higher rates of hyponatremia among children with SLE than those with JIA, consistent with the overall higher rates of organ dysfunction in those children. However, most of the children who received hypertonic saline did not have a diagnosis code for hyponatremia, suggesting that the hypertonic saline may have been given for cerebral edema, for seizure in the setting of suspected hyponatremia, or to prevent hyponatremia. Intracranial pressure monitoring and mannitol administration rates in our study were low, however, which suggests that few patients were known to have intracranial hypertension.

We found variation in treatment regimen for MAS between children with SLE and JIA. These conditions are rare and incompletely understood, and variation in therapy is not unexpected in the absence of evidence to guide providers in their care of patients with varying disease characteristics. We found it interesting that only children with underlying JIA received IL-1 antagonists, perhaps due to recent reports of effect in those patients9,22 and little available data to support its use and safety profile in children with SLE. The variation in immunosuppressive medication use across diagnosis categories may highlight differences in the way providers approach children with MAS; children with SLE, who tended to have more organ system dysfunction, more often received therapy that resembled the HLH-04 protocol (including dexamethasone and IVIG) than children with JIA.

There are several study limitations to consider. The PHIS database has advantages over traditional administrative databases including information regarding medications and utilization of imaging studies and laboratory tests, but it has the standard limitations of existing data. The database does not contain clinical information (e.g. laboratory or imaging results) beyond that discernible from CTC and ICD-9-CM codes. We identified patients based on diagnosis codes and not on patient symptoms, signs, laboratory results, or measures of disease severity. Our analysis of medical records from one PHIS hospital (n = 5) suggests that our inclusion criteria were valid. Two patients in our study had diagnoses of both JIA and Kawasaki Disease, and we classified those patients as having JIA based on reports of coronary dilation in JIA and a concern for misdiagnosis of children as having Kawasaki Disease rather than JIA.23

Our analyses of index admission outcomes are limited because the database does not contain physiologic data, and our ability to adjust for severity of illness at hospital or ICU admission is limited. We were concerned about induced bias if we included treatment variables (medications, critical care interventions, etc.) in an outcome model, and chose to present the data descriptively and in bivariate analyses to facilitate hypothesis generation for other studies.

It is possible that selection bias is present in comparisons of MAS severity between children with JIA and SLE. If providers tended to diagnose MAS in a child with JIA sooner than in a child with SLE, delaying diagnosis in the child with SLE until the MAS was more severe, then MAS in SLE would appear more severe overall. In children with either JIA or SLE, less severe or “subclinical”24–26 cases of MAS may not be diagnosed if they respond to immunosuppression given for a possible flare of the underlying disease. It is not known if this happens differentially between children with JIA and SLE.

Genetic abnormalities associated with HLH such as perforin and syntaxin mutations and MUNC13-4 anomalies are not coded in the PHIS database.2 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes may have limited sensitivity for viral infections and other conditions that may trigger episodes of HLH or MAS.2,3,27 Because our study only includes hospitalized patients diagnosed with MAS, the incidence of MAS complicating SLE and JIA cannot be estimated.

Conclusion

Among children with MAS complicating rheumatic diseases, organ system dysfunction is common during the index admission. Children with underlying SLE appear to have more organ system dysfunction at their index MAS episode than children with JIA. Children with underlying SLE and JIA tend to receive different treatment regimens for their MAS.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosures: Drs. Bennett, Fluchel, and Stone are partially supported by the Mentored Scholars Program for Translational Comparative Effectiveness Research, NIH/NCI Grant Number 1KM1CA156723.

Footnotes

Other Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Janka G. Hemophagocytic syndromes. Blood Rev. 2007;21(5):245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henter J, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler R, Filipovich A, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124–131. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stéphan J, Koné-Paut I, Galambrun C, Mouy R, Bader-Meunier B, Prieur A. Reactive haemophagocytic syndrome in children with inflammatory disorders. A retrospective study of 24 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40(11):1285–1292. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.11.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawhney S, Woo P, Murray K. Macrophage activation syndrome: a potentially fatal complication of rheumatic disorders. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85(5):421–426. doi: 10.1136/adc.85.5.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly C, Salvi S, McClain K, Hayani A. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(4):658–660. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pringe A, Trail L, Ruperto N, Buoncompagni A, Loy A, Breda L, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus: an under-recognized complication? Lupus. 2007;16(8):587–592. doi: 10.1177/0961203307079078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parodi A, Davi S, Pringe AB, Pistorio A, Ruperto N, Magni-Manzoni S, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus: a multinational multicenter study of thirty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(11):3388–3399. doi: 10.1002/art.24883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grom A. Macrophage activation syndrome and reactive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: the same entities? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15(5):587–590. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200309000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeft A, Hollister R, LaFleur B, Sampath P, Soep J, McNally B, et al. Anakinra for systemic juvenile arthritis: the Rocky Mountain experience. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15(4):161–164. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181a4f459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Son MB, Gauvreau K, Ma L, Baker AL, Sundel RP, Fulton DR, et al. Treatment of Kawasaki disease: analysis of 27 US pediatric hospitals from 2001 to 2006. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):1–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss PF, Klink AJ, Hexem K, Burnham JM, Leonard MB, Keren R, et al. Variation in inpatient therapy and diagnostic evaluation of children with Henoch Schonlein purpura. J Pediatr. 2009;155(6):812–818. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss PF, Klink AJ, Localio R, Hall M, Hexem K, Burnham JM, et al. Corticosteroids may improve clinical outcomes during hospitalization for Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):674–681. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [Accessed January 4th, 2011];Child Health Corporation of America. Available at http://www.chca.com/index_no_flash.html.

- 14.Conway PH, Keren R. Factors associated with variability in outcomes for children hospitalized with urinary tract infection. J Pediatr. 2009;154(6):789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldin AB, Sawin RS, Garrison MM, Zerr DM, Christakis DA. Aminoglycoside-based triple-antibiotic therapy versus monotherapy for children with ruptured appendicitis. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):905–911. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turney CM, Wang W, Seiber E, Lo W. Acute pediatric stroke: contributors to institutional cost. Stroke. 2011;42(11):3219–3225. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.614917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickey PW, Cape KE, Masuoka P, Campos JM, Pastor W, Wong EC, et al. A local, regional, and national assessment of pediatric malaria in the United States. J Travel Med. 2011;18(3):153–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Center for Health Statistics and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Last accessed April 11, 2012];Conversion Table of New ICD-9-CM Codes, October 2011. URL http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd9/CNVTB12.pdf.

- 19.Gupta AA, Tyrrell P, Valani R, Benseler S, Abdelhaleem M, Weitzman S. Experience with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome at a single institution. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(2):81–84. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181923cb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravelli A, Magni-Manzoni S, Pistorio A, Besana C, Foti T, Ruperto N, et al. Preliminary diagnostic guidelines for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr. 2005;146(5):598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamazawa K, Kodo K, Maeda J, Omori S, Hida M, Mori T, et al. Hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia, and hypouricemia in a girl with macrophage activation syndrome. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2557–2560. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruck N, Suttorp M, Kabus M, Heubner G, Gahr M, Pessler F. Rapid and sustained remission of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated macrophage activation syndrome through treatment with anakinra and corticosteroids. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(1):23–27. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318205092d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, Vaidyanathan B, Gayathri S, Rajam L. Systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis with macrophage activation syndrome misdiagnosed as Kawasaki disease: case report and literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fall N, Barnes M, Thornton S, Luyrink L, Olson J, Ilowite NT, et al. Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood from patients with untreated new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis reveals molecular heterogeneity that may predict macrophage activation syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(11):3793–3804. doi: 10.1002/art.22981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bleesing J, Prada A, Siegel DM, Villanueva J, Olson J, Ilowite NT, et al. The diagnostic significance of soluble CD163 and soluble interleukin-2 receptor alpha-chain in macrophage activation syndrome and untreated new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(3):965–971. doi: 10.1002/art.22416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behrens EM, Beukelman T, Paessler M, Cron RQ. Occult macrophage activation syndrome in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):1133–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keren R, Wheeler A, Coffin SE, Zaoutis T, Hodinka R, Heydon K. ICD-9 codes for identifying influenza hospitalizations in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(10):1603–1604. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.051525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]