Abstract

This case report describes an atypical clinical presentation of visceral leishmaniasis affecting the digestive tract and causing malabsorption syndrome in a patient without recognized immunosuppressive condition. After appropriate treatment for the classical visceral form of the disease, diarrhea persisted as the main symptom and massive infection by Leishmania was detected by histopathology analysis of the duodenal mucosa. Schistosoma mansoni coinfection was also confirmed and treated without impact on diarrhea. New course of amphotericin B finally led to complete improvement of diarrhea. Atypical visceral leishmaniasis involving the gastrointestinal tract is well recognized in HIV coinfection but very rare in immunocompetent patients. The factors determining the control or evolution of the Leishmania infection have not been completely identified. This case stresses the importance of atypical symptoms and the unusual location of visceral leishmaniasis, not only in immunodepressed patients, and raises the possible influence of chronic infection by S. mansoni reducing the immune response to Leishmania.

1. Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) due to (Leishmania) infantum (sin L. chagasi) is endemic in Brazil. The incidence in adult patients has increased in recent years [1]. Typical clinical features are fever, hepatosplenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinaemia, and pancytopenia. Cases of VL have also presented atypically involving the lungs, pleura, oral mucosa, larynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and skin [2, 3]. These atypical cases were described mostly in patients infected with HIV [4, 5] or with any recognized immunosuppressive condition such as diabetes, lymphoma and elderly [3, 6, 7]. It suggested that the clinical manifestations may be influenced by the immunological status of the host.

2. Case Report

A 42-year-old man presented with a six-month history of nonbloody diarrhea associated with the clinical triad of fever, splenomegaly, and pancytopenia. Anti-Leishmania antibodies serological tests (indirect immunofluorescence title 1 : 640 and rapid test with the recombinant k39) were positive. The diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis was firmed by the detection of amastigotes in a bone marrow aspirate smears. Because of upper gastrointestinal symptoms (mild dysphagia and vomiting), an esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed, revealing in duodenum the presence of erosions coated with fibrin, plates of enanthema, and thickened pleats with small whitish spots distributed diffusely. In a tissue fragment obtained by biopsy, the duodenal mucosa showed villous enlarged and filled with numerous histiocytes packed with intracytoplasmic round structures with morphology suggestive of amastigotes of Leishmania spp. The patient received liposomal amphotericin B, 4 mg/kg of body weight during 5 days with complete improvement of visceromegaly, fever and recovery of white blood cell and platelets counts. After treatment and hospital discharge, diarrhea and anemia persisted, and his condition continued to deteriorate. Four months later the patient was admitted once again to hospital with worsening diarrhea, dehydration, metabolic acidosis, and electrolyte imbalance. Blood tests revealed a normochromic normocytic anemia, profound hipoalbuminemia (1.9 g/dL), and a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (120 mm/1 hour). Laboratory examinations also revealed low serum folic acid and iron levels. Both vitamins were replaced and nutritional support was beginning. This time, an extensive search for parasites in stool microscopy was done and eggs of S. mansoni were identified on stool microscopy. The patient was treated with praziquantel 60 mg/kg of body weight. After four weeks, diarrhea remained unchanged, and his condition continued to deteriorate with anorexia and weight loss. Abdominal computer tomography showed mild splenomegaly, no lymphadenopathy, and a normal liver size. There was mild dilatation of intestinal loops of the colon. A bone marrow aspiration was also performed showing only reactive changes and no Leishmania amastigotes. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) assessment on whole blood and bone marrow samples showed positive results using the ribosomal RNA small subunit gene (SSU rRNA) from Leishmania spp. as DNA target. Patient's lymphocyte counts were TCD4+: 539/mm3, TCD8+: 503/mm3 e TCD3+: 1,094/mm3. A colonoscopy was normal. Despite the absence of symptoms of upper gastrointestinal system, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed, and it showed the presence of diffuse pallor in stomach and duodenum with swollen appearance without ulceration. Duodenal mucosa histopathology showed the persistence of amastigotes, as four months before (Figure 1). The immunohistochemical study [8] confirmed the presence of numerous immunolabeled amastigotes forms of Leishmania (Figure 2). Tests to detect anti-Trypanosoma cruzi antibodies, a protozoan also endemic in Brazil and with tropism for the gastrointestinal tract, and the anti-HIV testing were negative. The patient was treated with amphotericin B deoxycholate, 0.8 mg/kg of body weight for 30 days, and diarrhea resolved completely within two weeks. Two months after the end of treatment the patient had reached its normal weight and normalized erythrocyte levels. The plasmatic levels of IFN-γ and IL-10 were measured before and after treatment by sandwich-enzyme-linked immuonosorbent assay, as previously described [9]. The results were expressed as picograms per milliliter (pg/mL) based on a standard curve. IFN-γ was undetectable before and after treatment, while IL-10 levels decreased from 36 pg/mL at initial evaluation to 16.3 pg/mL (55% reduction) after amphotericin treatment and clinical improvement.

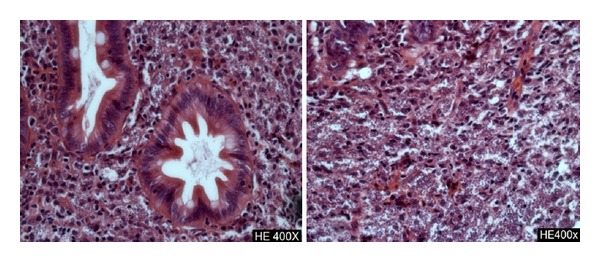

Figure 1.

Histological analysis of the duodenum showing extensive infiltration with Leishmania bodies (hematoxylin and eosin, ×400).

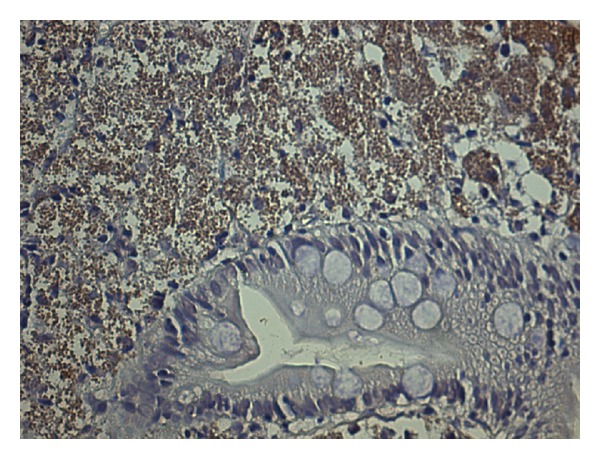

Figure 2.

The immunohistochemical study of duodenum fragment tissue confirming Leishmania presence.

3. Discussion and Literature Review

Gastrointestinal involvement in visceral leishmaniasis has been reported mainly in HIV/AIDS patients. Furthermore, although patients with VL may have symptoms of mild diarrhea, the presence of severe enteropathy, not accompanied by other classic signs of systemic involvement as the presenting feature, is rare: a literature review revealed only four case reports occurring in nonimmunosuppressed patients [7, 10, 11]. There are at least another five confirmed cases of intestinal involvement following the classical form of visceral leishmaniasis in immunocompetent individuals [12–14].

The exact pathogenesis of the diarrhea is not clear, it is suggested that symptoms in enteropathic VL may be a combination of parasitism of the reticuloendothelial cells of the submucosa, bacterial overgrowth, partial villous atrophy, competition between host and parasite for nutrients, altered motility, bile salt deconjugation, and lymphatic blockade [15, 16]. In the present case, as diarrhea does not respond to treatment and elimination of S. mansoni, it is reasonable to suppose that enteropathy was due to mucosal involvement by Leishmania rather than S. mansoni. On the other hand, the noncomplete response after a first-line treatment as liposomal amphotericin is intriguing. It should be noted that after the eradication of S. mansoni, another attempt of treatment with amphotericin has achieved an excellent response. In recent years, studies have demonstrated that helminthic infection (including S. mansoni) or products from their infections are able to downmodulate the type 1 TCD4+ T-cell inflammatory response [17, 18]. This temporal association and evidence already available on the immune modulation induced by helminthes encourage us to hypothesize that the interaction between the two agents (S. mansoni and Leishmania) contributed to this unusual manifestation occurrence and to a temporary resistance to treatment.

The factors determining the development of a clinically manifested form of VL (acute, classic, oligosymptomatic or atypical form) have not yet been completely identified. After inoculation of the promastigote form into the skin by the insect vector, a complex interaction between the parasite and the host immune response occurs, and its results can modulate the clinical presentation of VL [19]. With Leishmania spp. being recognized as an obligate intracellular parasite of macrophages, studies have demonstrated that the specific immunity in VL is mediated by TCD4+ T helper (Th) cells and that disease susceptibility is associated with the inability to produce a macrophage-stimulating cytokine profile (Th1 profile) including interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukins (IL)-2 and IL-12, while, on the other hand, an elevated production of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-4 (Th2 profile) as well as high levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) is observed [20]. In the reported case, we documented presence of IL-10 in the active phase of the disease but surprisingly, our data showed suppressed levels of IFN-γ, which could be due to S. mansoni infection and explain the massive and deep infection by Leishmania. This finding is in agreement with others who demonstrated that the addition of the S. mansoni antigens to peripheral blood mononuclear cells cultures of patients infected with L. braziliensis (stimulated with soluble Leishmania antigen) reduced IFN-γ and TNF production; conversely, these cells produced increased levels of IL-10 [18]. Another pathophysiological mechanism was suggested by an experimental study [21] that showed that S. mansoni-infected mice fail to control a superimposed L. donovani infection. The failure occurs despite the development of a functional anti-L. donovani Th1 response that can mediate granuloma formation and effective clearance of amastigotes from foci of infection in the hepatic parenchyma. Instead, anti-Leishmania immunity fails within the S. mansoni egg granuloma, consistent with a lack of L. donovani granuloma assembly in this tissue microenvironment and consequent lack of nitric oxide production.

Helminthes employ a range of immunomodulatory strategies to modulate the host immune response and utilize it to extend their longevity in the host and facilitate transmission. Studies of patients with concurrent infections of L. braziliensis and a helminthes infection have shown that these patients tend to present with smaller ulcers than patients without helminthes infections. However, the time for the lesion to heal was approximately double in coinfected patients [22]. In experimental studies, it has been shown that S. mansoni infection is able to downmodulate the Th1 inflammatory response that is implicated in several autoimmune diseases, such as type-I diabetes, encephalomyelitis, and psoriasis [23–25]. Moreover, there is evidence that Schistosoma sp. infection or its products have the potential to modulate Th2-immune responses that result in the pathology of allergic diseases [26]. Perhaps to control inflammation associated with the passage of S. mansoni eggs from the vascular compartment to the liver parenchyma, eggs inhibit toll-like receptors (TLRs-) mediated dendritic cells (DCs) activation and activate innate and adaptive immune responses that result in the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4 and IL-10. The importance of these pathways is attested to not only by their crucial role in the survival of schistosome-infected hosts but also in the ability of schistosomes and other helminthes to ameliorate Th1-response-mediated autoimmune pathologies [17]. As an example, asthmatic patients who are infected with S. mansoni have a less severe course of asthma, and it seems to be mediated by IL-10 [27].

4. Conclusion

We describe an unusual presentation of visceral leishmaniasis accompanied by intestinal involvement in an immunocompetent patient. Even with extensive investigation we did not find any immunosuppressive condition, except the S. mansoni coinfection. This case report might represent an example of the immune modulation induced by S. mansoni and can add to other evidence in the search for elucidating the complex mechanisms involved in the states of susceptibility and resistance to Leishmania infection. In addition, this report also shows that intestinal infection by Leishmania spp. must be included in the differential diagnosis for chronic diarrhea among patients with a previous history of leishmaniasis or living in an endemic area.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

G. F. Cota carried out the clinical assessment, conceived and wrote the paper; L. I. Gomes and B. F. Pinto performed the molecular tests; J. R. Santos-Oliveira and A. M. Da-Cruz carried out the cytokine determination; M. S. Pedrosa made the anatomopathological study; W. L. Tafuri performed the immunohistochemical study; A. Rabello critically reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final paper. G. F. Cota and A. Rabello are guarantors of the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by FAPEMIG (APQ001562-11 Universal). A. Rabello and A. M. Da-Cruz are investigators supported by CNPq.

References

- 1.Brasil Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Manual de Recomendações Para Diagnóstico, Tratamento e Acompanhamento de Pacientes Com a Coinfecção Leishmania-HIV. Brasil: Brasil Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica; 2011. (A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiseo D, Tosone G, Conte MCD, et al. Isolated laryngeal leishmaniasis in an immunocompetent patient: a case report. Infezioni in Medicina. 2008;16(4):233–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hicks L, Kant P, Tay PH, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis presenting with intestinal failure: a case report and literature review. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;21(1):117–122. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32830e6fdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal E, Marty P, Giudice P, et al. HIV and Leishmania coinfection: a review of 91 cases with focus on atypical locations of Leishmania . Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2000;31(4):1093–1095. doi: 10.1086/318135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laguna F, García-Samaniego J, Soriano V, et al. Gastrointestinal leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: report of five cases and review. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1994;19(1):48–53. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellul P, Piscopo T, Vassallo M. Visceral leishmaniasis diagnosed on duodenal biopsy. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;5(7):p. A26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Álvarez-Nebreda ML, Álvarez-Fernández E, Rada S, et al. Unusual duodenal presentation of leishmaniasis. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2005;58(12):1321–1322. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.027029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tafuri WL, Santos RDL, Arantes RME, et al. An alternative immunohistochemical method for detecting Leishmania amastigotes in paraffin-embedded canine tissues. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2004;292(1-2):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos-Oliveira JR, Regis EG, Leal RB, Cunha RV, Bozza PT, da-Cruz AM. Evidence that lipopolisaccharide may contribute to the cytokine storm and cellular activation in patients with visceral leishmaniasis. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2011;5(7):p. e1198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baba CS, Makharia GK, Mathur P, Ray R, Gupta SD, Samantaray JC. Chronic diarrhea and malabsorption caused by Leishmania donovani . Indian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;25(6):309–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salah HB, Mekni MA, Khanfir M, et al. Unusual presentation of visceral leishmaniasis in an immunocompetent patient. Medecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2006;36(3):167–169. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Challacombe ND, Wheeler EE, Phillips MJ, Eden OB. Clinical curio: Leishman donovan bodies in the duodenal mucosa of a child with kala-azar. British Medical Journal. 1983;286(6367):789 pages. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6367.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boukthir S, Mejri A, M’rad S, Barsaoui S. Visceral leshmaniasis diagnosed on duodenal biopsy in a child. Acta Gastro-Enterologica Belgica. 2003;66(3):258–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geramizadeh B, Fakhar M, Motazedian MH. Visceral leishmaniasis with duodenal involvement: three immunocompetent cases from southern Iran. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 2006;100(7):637–640. doi: 10.1179/136485906X112149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muigai R, Gatei DG, Shaunak S. Jejunal function and pathology in visceral leishmaniasis. The Lancet. 1983;2(8348):476–479. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thakur CP. Leishman donovan bodies in the duodenal mucosa of a child with kala-azar. British Medical Journal. 1983;287(6400):1221 pages. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6400.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearce EJ, Kane CM, Sun J, Taylor JJ, McKee AS, Cervi L. Th2 response polarization during infection with die helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni . Immunological Reviews. 2004;201:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bafica AMB, Cardoso LS, Oliveira SC, et al. Schistosoma mansoni antigens alter the cytokine response in vitro during cutaneous leishmaniasis. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(7):856–863. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000700012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gama ME, Costa JM, Pereira JC, Gomes CM, Corbett CE. Serum cytokine profile in the subclinical form of visceral leishmaniasis. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2004;37(1):129–136. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000100018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nylen S, Sacks D. Interleukin-10 and the pathogenesis of human visceral leishmaniasis. Trends in Immunology. 2007;28(9):378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassan MF, Zhang Y, Engwerda CR, Kaye PM, Sharp H, Bickle QD. The Schistosoma mansoni hepatic egg granuloma provides a favorable microenvironment for sustained growth of Leishmania donovani . American Journal of Pathology. 2006;169(3):943–953. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Neal SE, Guimaraes LH, Machado PR, et al. Influence of helminth infections on the clinical course of and immune response to Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;195(1):142–148. doi: 10.1086/509808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooke A, Tonks P, Jones FM, et al. Infection with Schistosoma mansoni prevents insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in non-obese diabetic mice. Parasite Immunology. 1999;21(4):169–176. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sewell D, Qing Z, Reinke E, et al. Immunomodulation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by helminth ova immunization. International Immunology. 2003;15(1):59–69. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atochina O, Harn D. Prevention of psoriasis-like lesions development in fsn/fsn mice by helminth glycans. Experimental Dermatology. 2006;15(6):461–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Araujo MI, Ribeiro De Jesus A, Bacellar O, Sabin E, Pearce E, Carvalho EM. Evidence of a T helper type 2 activation in human schistosomiasis. European Journal of Immunology. 1996;26(6):1399–1403. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardoso LS, Oliveira SC, Pacifico LGG, et al. Schistosoma mansoni antigen-driven interleukin-10 production in infected asthmatic individuals. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101(1) supplement:339–343. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000900055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]