Abstract

Background

Low fruit and vegetable ( FV) consumption is a key risk factor for morbidity and mortality. Consumption of FV is limited by a lack of access to FV. Enhanced understanding of interventions and their impact on both access to and consumption of FV can provide guidance to public health decision-makers. The purpose of this scoping review is to identify and map literature that has evaluated effects of community-based interventions designed to increase FV access or consumption among five to 18-year olds.

Methods

The search included 21 electronic bibliographic databases, grey literature, targeted organization websites, and 15 key journals for relevant studies published up to May 2011. Retrieved citations were screened in duplicate for relevance. Data extracted from included studies covered: year, country, study design, target audience, intervention setting, intervention strategies, interventionists, and reported outcomes.

Results

The search located 19,607 unique citations. Full text relevance screening was conducted on 1,908 studies. The final 289 unique studies included 30 knowledge syntheses, 27 randomized controlled trials, 55 quasi-experimental studies, 113 cluster controlled studies, 60 before-after studies, one mixed method study, and three controlled time series studies. Of these studies, 46 included access outcomes and 278 included consumption outcomes. In terms of target population, 110 studies focused on five to seven year olds, 175 targeted eight to 10 year olds, 192 targeted 11 to 14 year olds, 73 targeted 15 to 18 year olds, 55 targeted parents, and 30 targeted teachers, other service providers, or the general public. The most common intervention locations included schools, communities or community centres, and homes. Most studies implemented multi-faceted intervention strategies to increase FV access or consumption.

Conclusions

While consumption measures were commonly reported, this review identified a small yet important subset of literature examining access to FV. This is a critically important issue since consumption is contingent upon access. Future research should examine the impact of interventions on direct outcome measures of FV access and a focused systematic review that examines these interventions is also needed. In addition, research on interventions in low- and middle-income countries is warranted based on a limited existing knowledge base.

Background

Low fruit and vegetable (FV) consumption is one of the top 10 global risk factors for mortality according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. Increased FV consumption can help protect overall health status and reduce both disease risk and burden [2]. Fruit and vegetable intake among children is of particular interest due to growing recognition of the importance of nutrition for growth, development, and prevention of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and obesity [2]. A number of studies have shown that childhood FV consumption patterns and preferences are predictive of patterns in adolescence and adulthood [3-6]. It has been estimated that 2.7 million lives could be saved each year through increased and adequate FV consumption. In addition, this increased consumption of FV would decrease the worldwide non-communicable disease burden by almost 2% [7].

Consumption of FV is limited by a lack of access to FV, which is a conspicuous issue facing low- and middle-income countries, but also affects high-income countries [8]. While FV intake is directly associated with socioeconomic status, many individuals do not meet recommended guidelines for FV intake regardless of country of origin and income status [8]. A systematic review of potential determinants of FV intake and intervention strategies found that availability and accessibility of FV and preferences had the most consistent positive relationship with FV consumption [9]. Another more recent systematic review of determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents identified many individual level determinants including direct gradients associated with intake and socioeconomic status, home availability and accessibility, and parental intake patterns [8]. The environmental factors that influence consumption of FV extend beyond the individual to include: physical, economic and social factors; supply, availability and accessibility (includes costing); availability of FV in stores in the local community, schools, community-based programs; and policies at global, regional, national and local levels [8-11]. Nutrition knowledge, preferences, and self-efficacy are also associated with increased intake of FV [8,12,13] and therefore have been included as secondary outcomes of interest for this review. Enhanced understanding of relevant intervention research and its impact on both access to and consumption of FV, as well as chronic disease health indicators, can provide guidance to public health decision-makers and policy-makers in the establishment and maintenance of effective and supportive nutritional programs.

Three reviews have previously examined the effect of community interventions to increase FV consumption, however, one review has not been updated in over 10 years [14] and the two others were limited to school-based interventions in high-income countries [15,16]; in these the previous reviews, the important issue of access to FV was not addressed [14-16]. The purpose of this scoping review is to identify and map literature that has evaluated the effects of community-based interventions designed to increase FV access and/or consumption among five to 18-year olds. The effectiveness of upstream interventions targeting children and adolescents (18 years and under) is of particular interest to decision makers since FV consumption patterns established in childhood tend to persist through adulthood [3-6]. We are aware of a potentially complementary review that intends to examine interventions to increase FV consumption in preschool children (under 5 years) [17] and therefore focused on 5 to 18 year olds. Due to the large scope of this review topic, interventions focused solely on adults or specialized populations such as those with a specific chronic disease were considered beyond the scope of this review.

The initial step in this scoping review involved defining the research question in a PICOS (Population-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome-Study Design) format. The PICOS question was defined by the research team and refined in collaboration with two public health librarians who subsequently implemented the search.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

Participants

This review includes populations from low-, middle-, and high-income countries and focuses on children aged five to 18 years.

Interventions

We included interventions delivered to anyone that brings about changes in FV access and consumption for five to 18 year olds (i.e., parents, communities, and others within the population, including children themselves). The following types of community-based interventions were included:

• Nutrition-friendly schools initiatives

• Child nutrition programs such as breakfast/lunch and summer food service programs

• Community programs (e.g., community gardens)

• Health education related to increased FV consumption

• Economic supplements and subsidies to purchase FV, including subsidies for schools and food stamp programs

• Environmental school change strategies (e.g., changing the types of foods provided in cafeterias or vending machines)

• Environmental interventions/industry partnerships focused on point-of-purchase (e.g., restaurants, grocery store distributors and retailers); this might include campaigns to draw attention to healthier products in grocery stores or to highlight the benefits of certain foods or within store promotions and costs

• Population level initiatives (e.g., agricultural policies)

• Internet, telephone and media interventions

• Farm-to-school programs that use locally produced foods

• Social marketing campaigns

• Policies that affect accessibility factors

• Policies that seek to increase FV consumption (i.e., school board level, provincial/national level).

Locations

Intervention locations included: homes, schools, health departments, religious institutions, family/child centres, community/recreation centres, non-governmental organizations, and primary healthcare settings. We excluded programs or strategies delivered through hospitals; outpatient clinics located within hospital settings; commercial programs, such as Health Check; universities/colleges; and metabolic or weight loss clinics.

Outcomes of interest

Our primary outcomes included measures of both access to and consumption of fruit, vegetables, or both. Evidence of intervention effects included: measures at individual, family, school or community levels. Measures of FV access included: FV supply (i.e., market inventory); and change in food environments, food disappearance, and food sales (in cafeterias and grocery stores). Food supply measures included information about which food items are distributed to different regions and areas. Market inventory refers to records a food supply organization keeps about which foods are being ordered or are available. Measures of FV consumption included: diet and food intake records, self-reported and/or reported by parents, teachers or both; food frequency questionnaires/balance sheets; food wastage and plate waste; and micronutrient measures (i.e., biomarkers of exposure to FV).

Our secondary outcomes included: awareness of importance/impact of FV consumption among targeted individuals, attitudes towards consumption of FV, general health measures including changes in weight, and adverse outcomes or unintended consequences.

Study designs

Acceptable designs for this review included systematic reviews (included research syntheses and meta-analyses), randomized and non-randomized studies (including cluster-controlled and controlled time series), interrupted time series (to assess changes that occur over time), and before-after studies with controls. Relevant clusters within studies, included school units, classrooms or communities rather than individuals as the unit of analysis.

Search strategy

Our search strategy included: electronic bibliographic databases; grey literature databases; reference lists of key articles; targeted internet searching of key organization websites; and hand searching of key journals.

We searched the following databases, adapting search terms according to the requirements of individual databases in terms of subject heading terminology and syntax: MEDLINE and Pre-MEDLINE; EMBASE; CINAHL and Pre-CINAHL; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); the Cochrane Public Health Group Specialized Register; PsycINFO; Dissertation Abstracts; ERIC; Effective Public Health Practice Project Database; Sociological Abstracts; Applied Social Sciences Index; CSA Worldwide Political Science Abstracts; ProQuest (ABI/Inform Global); PAHO Institutional Memory Database; WHO Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition; Healthstar; Current Contents; ScienceDirect; and LILACS. The original search was conducted on August 17, 2010 and was updated on May 31, 2011, searching each database from its beginning. Our search strategy for the electronic databases is shown in Appendix 1 (Additional file 1).

We used the Grey Matters search tool, Federated Search for applicable policy documents, the System for Grey Literature in Europe and the Global Health Database to search for relevant grey literature. We conducted a hand search of the reference lists of all relevant articles for any additional references. We also searched key sites, including the World Health Organization ( http://www.who.int/en/), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations ( http://www.fao.org/), and Pan American Health Organization ( http://new.paho.org/). Further, we had searched the following journals (for the 12-month period prior to the date of search [Aug. 17, 2010]): Health Policy; Journal of Public Health Policy; Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law; Health Economics, Policy, and Law; American Journal of Clinical Nutrition; Journal of Health Services Research; American Journal of Public Health; Journal of the American Dietetic Association; Nutrition Reviews; Maternal and Child Nutrition; Nutrition and Dietetics; Nutrition Research; Public Health Nutrition; American Journal of Preventive Medicine and Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition. Journal selection for hand searching was guided by consultation with experts and our review advisory committee.

Study selection

A librarian conducted a search for relevant literature. The search strategy identified titles and abstracts. Teams of two reviewers conducted relevance screening to eliminate obviously irrelevant studies; each person independently reviewed titles and abstracts for relevance screening. All articles selected by either team member were retrieved for full text review. For citations with no abstract, the full article was retrieved for full text relevance screening.

Review teams independently examined the full text of retrieved articles for relevance. A third reviewer was consulted to resolve any disagreements related to inclusion of articles. Studies excluded following full text reviews and reasons for exclusion were documented. Articles in English, French and Spanish were reviewed at the inclusion screening stages (title/abstract and full text review).

Data extraction and sorting

For all included studies, data were extracted by two reviewers and included: year of publication, study design, types of outcomes reported and research location. When there was more than one publication per study, these citations were grouped into ‘projects’. Only articles published in English and French underwent data extraction due to the fluency of available reviewers.

Results

Citation retrieval

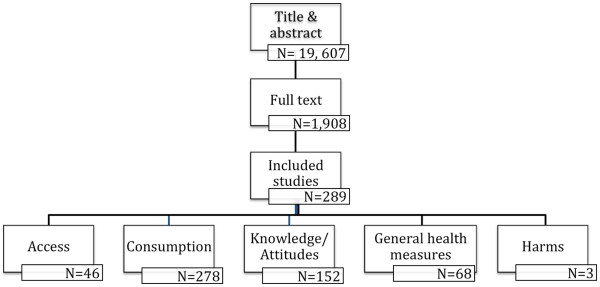

The search strategy retrieved nearly 23,000 citations, which were reviewed by research assistants to remove duplications. Of the citations identified, 22,287 (97.3%) were found through published literature databases, 156 (0.7%) through grey literature searching, and 468 (2.0%) through hand searching relevant journals. Two reviewers independently examined the titles and abstracts of 19,607 unique citations for relevance. Following title and abstract review, 17,699 (90.3%) citations were excluded and 1,908 (9.7%) remained to undergo full text relevance screening. Following full text review, 1,619 (84.9%) studies were excluded with 289 (15.1%) unique studies remaining. Of the citations excluded during full text review, 52 (3.2%) were excluded because they were published in a language other than English or French, 366 (22.6%) had target audiences that did not include children aged five to 18 years or persons who had influence over FV access or consumption for children, 232 (14.3%) did not use a study design appropriate for evaluating interventions, 638 (39.4%) did not evaluate a relevant intervention or policy, 236 (14.6%) did not have baseline comparison data, and 95 (5.9%) did not report outcomes of interest for five to 18 year olds. See Figure 1 for a flowchart of literature retrieved, levels of screening, included studies, and types of outcomes.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of screening process for unique citations retrieved, number of included studies at each level of screening, and outcomes reported in included studies.

The final 289 unique studies were found in the form of journal articles and reports. The published citations appeared in 100 periodicals with 89 published in five journals. These included 12 articles published in the Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior, 14 in the Journal of Nutrition Education, 17 in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 19 in Preventive Medicine, and 27 in Public Health Nutrition. The year of publication for included articles ranged from 1970 to 2011, with 230 studies published during or since 2001. See Appendix 2 (Additional file 2) for details of all included studies, such as author(s), title, year, location, design, target population, and types of outcomes measured. As seen in Appendix 2, very few studies from low- or middle-income countries were identified.

Study designs and outcomes

The final 289 unique studies included 30 knowledge syntheses (including narrative systematic reviews and meta-analyses) [9,14,15,18-44], 27 randomized controlled trials [45-71], 55 quasi-experimental studies [72-126], 113 cluster controlled studies [94,127-237], 60 before-after studies [238-306], one mixed method study [307], and three controlled time series studies [308-310]. Several of studies had multiple publications reporting results (e.g., outcomes reported at different time points): Ammerman et al. [18,19,311], Bere [139,312,313]; Bere et al. [140,314,315], Byrd-Bredbenner et al. [146,316], Ciliska et al. [15,317], Chen et al. [48,318], Colby [247,319], Covelli [79,320], Cullen et al. [253,321], Gortmaker et al. [163,322], Haarens et al. [166,323], Hendy et al. [55,324], Hollar et al. [96,325,326], Hopper et al. [174,327], Jimenez et al. [100,328,329], Latimer [273,330], Lautenschlager and Smith [275,331], Lytle et al. [191,332,333], McCormick et al. [285,334], Nicklas et al. [198,335], Parmer et al. [203,336], Reinaerts et al. [217,337], Tak et al. [121,338,339], Tanner et al. [120,340], Taylor et al. [229,341], Thomas et al. [42,342], Thompson et al. [231,232,343], Walker [267,303], Wardle et al. [69,344], and Wrigley [306,345]. The number of citations for each study design and the reported outcome measures are summarized in Table 1. All study tallies included in the following sections and associated (Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5) include both knowledge syntheses and primary studies.

Table 1.

Study design and outcomes

| Study design | Access | Consumption | Knowledge/ Attitudes/ Awareness | General health measures | Harms | Total Studies by Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Systematic Review |

8 |

30 |

18 |

9 |

0 |

30 |

|

RCT |

2 |

27 |

14 |

12 |

0 |

27 |

|

Quasi-Experimental |

6 |

51 |

26 |

12 |

0 |

55 |

|

Cluster Controlled |

11 |

107 |

59 |

25 |

3 |

113 |

|

Before-After (no control) |

18 |

59 |

31 |

9 |

0 |

60 |

|

Mixed Method |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Controlled Time Series | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

Table 2.

Target audience and outcomes

| Audience | Access | Consumption | Knowledge/ Attitudes/ Awareness | General health measures | Harms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

5 - 7 year olds |

16 |

109 |

55 |

21 |

1 |

|

8 - 10 year olds |

30 |

175 |

98 |

40 |

3 |

|

11 - 14 year olds |

29 |

187 |

102 |

44 |

3 |

|

15 - 18 year olds |

12 |

71 |

42 |

21 |

0 |

|

Parents |

15 |

57 |

33 |

22 |

1 |

|

Teachers/ school personnel |

3 |

10 |

9 |

6 |

1 |

|

Other service providers |

3 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

| General public | 6 | 14 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

Table 3.

Intervention locations and outcomes

| Location | Access | Consumption | Knowledge/ Attitudes/ Awareness | General health measures | Harms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

School |

33 |

229 |

130 |

47 |

3 |

|

Supermarket |

2 |

9 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

|

Religious institution |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

Community |

12 |

37 |

22 |

15 |

1 |

|

Camps |

2 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

|

Primary care setting |

0 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

|

Home |

9 |

38 |

22 |

10 |

1 |

|

Internet |

2 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

| Other | 5 | 26 | 15 | 9 | 0 |

Table 4.

Intervention strategies and outcomes

| Intervention Strategy | Access | Consumption | Knowledge/ Attitudes/ Awareness | General health measures | Harms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Class series |

14 |

172 |

107 |

35 |

2 |

|

Community-wide intervention |

9 |

31 |

16 |

14 |

0 |

|

Comprehensive school health |

4 |

17 |

16 |

6 |

0 |

|

Group discussion |

6 |

43 |

29 |

13 |

0 |

|

Individual counseling/ teaching |

3 |

32 |

16 |

9 |

0 |

|

Interactive approach |

25 |

166 |

100 |

52 |

1 |

|

Parent involvement |

16 |

105 |

63 |

34 |

1 |

|

Pedagogical/ lecture approach |

2 |

28 |

14 |

10 |

0 |

|

Peer-led |

2 |

19 |

16 |

5 |

0 |

|

Community garden |

4 |

19 |

13 |

2 |

0 |

|

Policy |

16 |

37 |

15 |

8 |

1 |

|

Marketing |

14 |

51 |

31 |

15 |

1 |

|

Educational written material |

19 |

127 |

76 |

36 |

2 |

|

Behavior modification |

8 |

67 |

38 |

23 |

1 |

|

Creating supportive environments |

15 |

79 |

49 |

27 |

0 |

|

Provision of fruit and/or vegetables |

23 |

116 |

64 |

20 |

2 |

| Other | 32 | 144 | 76 | 32 | 2 |

Table 5.

Intervention delivery and outcomes

| Intervention delivered by | Access | Consumption | Knowledge/ Attitudes/ Awareness | General health measures | Harms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Teacher |

14 |

130 |

85 |

31 |

3 |

|

Principal/school administration |

9 |

30 |

14 |

6 |

1 |

|

Community lay person |

3 |

15 |

11 |

4 |

0 |

|

Peer |

1 |

17 |

15 |

4 |

0 |

|

Farmer |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Dietician |

2 |

18 |

8 |

7 |

0 |

|

Other health professional |

2 |

23 |

10 |

8 |

0 |

|

Other school personnel |

10 |

49 |

29 |

9 |

2 |

|

Health department or Ministry of Health |

3 |

11 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

| Other | 29 | 148 | 80 | 37 | 1 |

Intervention target populations and outcomes

The target audiences for interventions may have included sub-groups within the age range of five to 18 years; however, adults who influence children’s nutritional access or consumption may also have been targeted. For interventions that targeted these ‘other’ audiences, the articles needed to report outcomes for five to 18 year olds to be included in this review. Of the unique studies, 110 targeted five to seven year olds, 175 targeted eight to 10 year olds, 192 targeted 11 to 14 year olds, 73 targeted 15 to 18 year olds, 55 targeted parents, 12 targeted teachers, five targeted other service providers, and 13 targeted the general public. For a breakdown of outcomes reported in both knowledge syntheses and primary studies by target audience see Table 2. Additional file 2 summarizes target audiences for each individual study together with other study features.

Intervention locations and outcomes

Each unique citation was also examined to identify the locations in which interventions were delivered. Interventions were delivered in a wide variety of locations: schools (n = 233), supermarkets (n = 9), religious institutions (n = 2), community or community centres (n = 37), camps (n = 7), primary care settings (n = 5), homes (n = 38), by internet (n = 6), and other locations (n = 26). The other locations included after school programs, Boy and Girl Scout troop meetings, child care centres, farms or farmers’ markets, pediatricians’ offices, YMCAs and youth programs. The outcomes measured in various locations of intervention delivery are shown in Table 3 (includes knowledge syntheses and primary studies). Many studies were delivered in multiple locations such as in schools plus community [30,40,42,100,246,282], plus home [26,31,94,102,110,144,145,154,174,189,197,205,254,281,327,346], plus supermarkets [137], plus after school programs [43], plus the internet [103], plus other [9,27,67,195,257,286], or schools plus two or more other locations [19,23,24,29,35-38,88,157,159,161,317]. Several other studies combined a general community location plus a supermarket [82], camp [265], home [20,135], religious institution [53], other [181], or home plus internet components [231]. Three studies implemented interventions in primary care settings plus the home [25,62,63]. Others primarily targeted the home with other components delivered either by internet [251], in other locations [151,231,270], or both [46]. One study delivered an intervention within a religious institution combined and a camp [247].

Intervention strategies and outcomes

Most studies implemented multi-faceted intervention strategies with only approximately 10% of studies implementing individual strategies to increase FV access or consumption. An example of a multiple intervention strategy is an educational series delivered primarily in a school with an added homework component to engage parents. The outcomes measured using different intervention strategies are shown in Table 4 (knowledge syntheses and primary studies).

Intervention delivery and outcomes

Unique studies were also examined to determine who had delivered interventions. Most often teachers (n = 130), school administrators (n = 32) and/or other school personnel (n = 49) were involved in delivery. In other cases, dieticians (n = 19), health departments or health ministries (n = 11), and other health professionals (n = 23) were responsible for implementation. Community lay persons and peers were involved in delivering interventions in 12 and 15 studies, respectively. In some studies the researchers implemented the interventions (n = 13), whereas in many others it was not stated who delivered the interventions. A breakdown of the outcomes and by whom the interventions were delivered (knowledge syntheses and primary studies) is summarized in Table 5. Some studies had interventions that were delivered by multiple individuals, such as teachers plus another community or school individual (e.g., administrator, health professional, other school personnel, researcher) [21,26,29,37,38,41,52,59,72,97,103-105,118,121,131,134,137,140,144,157,161,198,200,214,217,218,226,249,258,261,274,291,301,309,310,317,338,342]; teachers plus 2 or more other individuals [15,23,28,31,36,43,74,75,88,102,110,119,127,137,159,166,172,175,199,202,205,213,219,246,262,276,299]; Health Department or Ministry of Health together with school administrators or other school personnel [224,264,307]; peers plus teachers and/or administrators [16,30,35,40,55,143,155,190]; administrators and other school personnel [193,297,305]; peers plus other school personnel [55,160]; peers plus administrators plus other school personnel [173]; peers plus dietician [187,277]; peers plus community members [124]; dietician plus other school or health professionals [19,115,250,318]; and other school or health professionals plus other community or health providers [191,230,286].

Knowledge syntheses summary

This scoping review identified 30 systematic reviews, all of which reported on consumption outcomes; only eight reported on access outcomes as well. Approximately two-thirds reported on our secondary outcomes of interest that included knowledge, attitudes, awareness, and general health measures. None of the included systematic reviews reported on harms.

Discussion

The Cochrane Public Health Group acknowledges that a scoping review is a critical step in defining a systematic review question [347]. We identified a large volume of interventional research found within peer-reviewed and grey literature associated with FV access and consumption. Using a scoping review process [347], we categorized these studies with respect to outcomes based on a number of parameters such as study design, target audience, intervention location, intervention strategy, and intervention deliverer.

The predominant outcome measure was consumption. In comparison, harm was included as an outcome measure in an extremely small number of studies, which may indicate that there are few risks or potential harms associated with interventions used to increase FV consumption. It also possible that harms were overlooked given that few of these studies evaluated interventions implemented in low- or middle-income countries where populations could be more vulnerable. The bias of studies toward high-income countries and not low- and middle-income countries warrants further investigation as intervention effectiveness may vary across these populations.

While consumption measures were commonly reported, this review identified a small yet important subset of literature examining the effectiveness of interventions that increase access to FV. We believe this to be a relatively overlooked but critically important issue since consumption of FV is contingent upon access to them. A number of articles discussed FV accessibility; however, many of these studies lacked before-after comparison data or other comparison groups. These studies were excluded during full text relevance screening since they did not evaluate the impact of an intervention or policy. Specific measures of access were lacking in included studies; authors often identified a goal of evaluating the impact of interventions or policies to increase FV access but measured changes in consumption behaviors as a proxy for access.

Measuring FV access seems to be further complicated by a lack of consistent, meaningful, validated instruments; across the studies there was great variability in the ways access was measured. While some studies evaluated the impact of policy change on FV access and consumption, very few looked at population level initiatives or reported on population subgroups to be able to evaluate their impact on children aged five to 18 years. Further, despite the potential benefits of increasing access to FV, only a small number of studies partnered with farms or involved establishing community gardens. We also did not find any studies that evaluated changes in food supply or market inventory, two additional factors that influence access to and consequently consumption of FV.

This review has several methodological and operational limitations. A number of studies that examined knowledge, attitudes, awareness, and general health measures were excluded if they did not also examine either of our primary outcomes of access or consumption. It is possible, that relevant studies that explored our secondary outcomes were missed as a result of these methodological considerations. Operationally, the included studies were limited by the language fluency of the reviewers. Five articles published in Spanish were reviewed and included through titles and abstracts and full text phases, however because the Spanish-speaking reviewers were not available at the data extraction stage we excluded these papers. Data extraction was limited to studies published in English or French. Finally, including participants older than 18 years would have broadened the scope of available literature but the number of studies would not have been manageable for this scoping review. Therefore, the findings of this review are limited to children aged five to 18 years.

Conclusions

This scoping review sought to identify and map literature that has evaluated the effects of community-based interventions designed to increase FV access and/or consumption among five to 18-year olds. A variety of interventions have been used to support and increase FV consumption. Schools were the most common location for interventions, which were typically multi-faceted, targeted at individuals less than 15 years of age, and delivered by teachers or other school personnel. Additional research on implementing interventions in low- and middle-income countries is warranted based on the limited literature focusing on those populations. Finally, a somewhat narrow field of literature was identified with respect to FV access, suggesting that future research examining interventions to increase FV consumption should include direct outcome measures of FV access. Previously published syntheses revealed a gap in our understanding of the effectiveness of interventions that increase access to FV, since no syntheses that examined access to fruit and vegetables among children were found through our comprehensive literature search. While this scoping review identified several knowledge synthesis products, all were focused on FV consumption. Since consumption is contingent upon access, a focused systematic review that examines these interventions is needed. Such a review should examine and synthesize literature that seeks to increase access through interventions including (but not limited to): influencing FV supply, changing food environments, and enhancing FV sales in cafeterias and grocery stores.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RG participated in the conception and methodological design of this review, participated in searching and reviewing studies, and drafted the manuscript. DFL, DC, and LP participated in the conception and methodological design of this review, participated in searching and reviewing, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Search strategy.

Details of included studies.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Ganann, Email: ganannrl@mcmaster.ca.

Donna Fitzpatrick-Lewis, Email: fitzd@mcmaster.ca.

Donna Ciliska, Email: ciliska@mcmaster.ca.

Leslea Peirson, Email: peirson@mcmaster.ca.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Fruit and Vegetable Access and Consumption Review Study Team, Rachel Warren, and Sharon Peck-Reid for their assistance in completing this scoping review.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lien N, Lytle LA, Klepp KI. Stability in consumption of fruit, vegetables, and sugary foods in a cohort from age 14 to age 21. Prev Med. 2001;33(3):217–226. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle LA, Kubik MY. Nutritional issues for adolescents. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17(2):177–189. doi: 10.1016/S1521-690X(03)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelder SH, Perry CL, Klepp KI, Lytle LL. Longitudinal tracking of adolescent smoking, physical activity, and food choice behaviors. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(7):1121–1126. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvaavik E, Andersen LF, Klepp KI. The stability of soft drinks intake from adolescence to adult age and the association between long-term consumption of soft drinks and lifestyle factors and body weight. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(2):149–157. doi: 10.1079/phn2004669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, Altmann DR, McKee M. The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(2):100–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krolner R, Rasmussen M, Brug J, Knut-Inge K, Wind M, Due P. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Part II: qualitative studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):112. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette L, Brug J. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among 6-12-year-old children and effective interventions to increase consumption. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2005;18(6):431–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2005.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodor JN, Rose D, Farley TA, Swalm C, Scott SK. Neighbourhood fruit and vegetable availability and consumption: the role of small food stores in an urban environment. Public Health Nutr. 2007;11(4):413–420. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen M, Krolner R, Klepp KI, Lytle L, Brug J, Bere E, Due P. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Part I: quantitative studies. J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3(22): . doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-22. (Epublication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Crawford D, Mishra G. Socio-economic inequalities in women's fruit and vegetable intakes: a multilevel study of individual, social and environmental mediators. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(5):623–630. doi: 10.1079/phn2005897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansdottir AG, Thorsdottir I, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Due P, Wind M, Klepp KI. Determinants of fruit and vegetable intake among 11-year-old schoolchildren in a country of traditionally low fruit and vegetable consumption. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:41. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciliska D, Miles E, O'Brien MA, Turl C, Tomasik HH, Donovan U, Beyers J. Effectiveness of community-based interventions to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. J Nutr Educ. 2000;32(6):341–352. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(00)70594-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Sa J, Lock K. School-based Fruit and Vegetable Schemes: A review of the Evidence. UK: Department of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine London; 2007. pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Noguera M, Tort S, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Bonfill X. Primary school interventions to promote fruit and vegetable consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2011;53(1–2):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfenden L, Wyse RJ, Britton BI, Campbell KJ, Hodder RK, Stacey FG, McElduff P, James EL. Interventions for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in preschool aged children (Protocol) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; : . doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008552.pub2. Issue 6. Art. No.: CD008552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman A, Lindquist C, I. Research Triangle, C. Research Triangle Institute-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice, S. United, R. Agency for Healthcare, and Quality. Evidence report/Technology Assessment AHRQ Publication. Vol. no. 25. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Rockville; 2001. The efficacy of interventions to modify dietary behavior related to cancer risk. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman AS, Lindquist CH, Lohr KN, Hersey J. The efficacy of behavioral interventions to modify dietary fat and fruit and vegetable intake: a review of the evidence. Prev Med. 2002;35(1):25–41. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti PR, Krasevec J, FitzGerald S. A review of the effectiveness of agriculture interventions in improving nutrition outcomes. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:599–609. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchett H. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among British primary schoolchildren: a reivew. Heal Educ. 2003;103(2):99–109. doi: 10.1108/09654280310467726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K, Waters E, O'Meara S, Summerbell C. Interventions for preventing obesity in childhood. A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2001;2(3):149–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SA, Stables G. Environmental interventions to promote vegetable and fruit consumption among youth in school settings. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 part 1):593–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings G, Stead M, McDermott L, Forsyth A, MacKintosh A, Rayner M. Review of Research on the Effects of Food Promotion to Children. Glasgow, Scotland: Food Standards Agency by the Centre for Social Marketing, the University of Strathclyde; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hingle MD, O'Connor TM, Dave JM, Baranowski T. Parental involvement in interventions to improve child dietary intake: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2010;51(2):103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howerton MW, Bell BS, Dodd KW, Berrigan D, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Nebeling L. School-based nutrition programs produced a moderate increase in fruit and vegetable consumption: Meta and pooling analyses from 7 studies. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(4):186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC. Fruit and vegetable availability: a micro environmental mediating variable? Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(7):681–689. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007441441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaime PC, Lock K. Do school based food and nutrition policies improve diet and reduce obesity? Prev Med. 2009;48(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepson R, Harris F, MacGillivray S, Kearney N, Rowa-Dewar N. A review of the Effectiveness of Interventions, Approaches and Models at Individual, Community and Population Level that are Aimed at Changing Health Outcomes Through Changing Knowledge Attitudes and Behaviour. London: NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence); 2006. pp. 1–218. [Google Scholar]

- Knai C, Pomerleau J, Lock K, McKee M. Getting children to eat more fruit and vegetables: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2006;42(2):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremers SPJ, de Bruijn GJ, Droomers M, van Lenthe F, Brug J. Moderators of environmental intervention effects on diet and activity in youth. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(2):163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissau I. Prevention of overweight in the school arena. Acta Paediatrica. 2007;96(Supplement 454):12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur DB. Heart healthy eating behaviors of children following a school-based intervention: a meta-analysis. Issues Compr Pediatric Nurs. 1998;21(1):35–48. doi: 10.1080/01460869808951126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd J, Burns C, Lucas P, Haikerwal A, Waters E. The effectiveness of nutrition interventions on dietary outcomes by relative social disadvantage: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(7):573–579. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.066357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Escamilla R, Hromi-Fiedler A, Vega-Lopez S, Bermudez-Millan A, Segura-Perez S. Impact of peer nutrition education on dietary behaviors and health outcomes among Latinos: a systematic literature review. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40(4):208–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau J, Lock K, Knai C, McKee M. Effectiveness of Interventions and Programmes Promoting Fruit and Vegetable Intake in Individuals of all Ages. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. pp. 1–133. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-O'Brien R, Story M, Heim S. Impact of garden-based youth nutrition intervention programs: a review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe L, Hunt P, Bradshaw H, Rayner M. Health promotion interventions to promote healthy eating in the general population: a review. Health Promot Eff Rev. 1997;6:198. [Google Scholar]

- Sahay TB, Ashbury FD, Roberts M, Rootman I. Effective components for nutrition interventions: a review and application of the literature. Heal Promot Pract. 2006;7(4):418–427. doi: 10.1177/1524839905278626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J, Harden A, Rees R, Brunton G, Garcia J, Oliver S, Oakley A. Young people and healthy eating: a systematic review of research on barriers and facilitators. Heal Educ Res. 2006;21(2):239–257. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerbell CD, Waters E, Edmunds LD, Kelly S, Brown T, Campbell KJ. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005; (3):CD001871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H, Ciliska D, Micucci S, Wilson-Abra J, Dobbins M. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Enhancement and Obesity Prevention Program in Children and Youth. Hamilton: Effective Public Health Practice Project; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van Cauwenberghe E, Maes L, Spittaels H, van Lenthe FJ, Brug J, Oppert JM, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Effectiveness of school-based interventions in Europe to promote healthy nutrition in children and adolescents: systematic review of published and 'grey' literature. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(6):781–797. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall J, Mhurchu CN, Blakely T, Rodgers A, Wilton J. Effectiveness of monetary incentives in modifying dietary behavior: a review of randomized, controlled trials. Nutr Rev. 2006;64(12):518–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Thompson D, Buday R, Jago R, Griffith MJ, Islam N, Nguyen N, Watson KB. Video game play, child diet, and physical activity behavior change: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, Cullen KW, Thompson DI, Nicklas T, Zakeri IF, Rochon J. The Fun, Food, and Fitness Project (FFFP): The Baylor GEMS pilot study. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13(1 SUPPL. 1):S30–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech BM, Klesges RC, Kumanyika SK, Murray DM, Klesges L, McClanahan B, Slawson D, Nunnally C, Rochon J, McLain-Allen B, Pree-Cary J. Child- and parent-targeted interventions: the Memphis GEMS pilot study. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13(1 Suppl 1):S40–S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Weiss S, Heyman MB, Cooper B, Lustig RH. The efficacy of the web-based childhood obesity prevention program in chinese american adolescents (web abc study) J Adolesc Heal. 2011;49(2):148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.11.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBar LL, Ritenbaugh C, Aickin M, Orwoll E, Elliot D, Dickerson J, Vuckovic N, Stevens VJ, Moe E, Irving LM. Youth: a health plan-based lifestyle intervention increases bone mineral density in adolescent girls. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160(12):1269–1276. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.12.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(3):171–178. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Rose E, Matz PE, Pietrobelli A, Epstein LH. Co-twin control designs for testing behavioral economic theories of child nutrition: methodological note. Int J Obes. 2006;30(10):1501–1505. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis M, Nichols SSD, Dalrymple N. The effects of a school-based intervention programme on dietary intakes and physical activity among primary-school children in Trinidad and Tobago. Public Health Nutrition. 2010;13(5):738–747. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Rydell S, Kubik MY, Lytle L, Boutelle K, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Dudovitz B, Garwick A. Healthy home offerings via the mealtime environment (HOME): feasibility, acceptability, and outcomes of a pilot study. Obesity. 2010;18(SUPPL. 1):S69–S74. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton L, Povey R, Clark-Carter D. Promoting children's fruit and vegetable consumption: interventions using the Theory of Planned Behaviour as a framework. Br J Heal Psychol. 2007;12(4):639–650. doi: 10.1348/135910706X171504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy HM, Williams KE, Camise TS. "Kids Choice" school lunch program increases children's fruit and vegetable acceptance. Appetite. 2005;45:250–263. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaime PC, Machado FM, Westphal MF, Monteiro CA. Nutritional education and fruit and vegetable intake: a randomized community trial. Revista De Saude Publica. 2007;41(1):154–157. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102006005000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston CA, Palcic JL, Tyler C, Stansberry S, Reeves RS, Foreyt JP. Increasing vegetable intake in mexican-american youth: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(5):716–720. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPorte MR, Gibbons CC, Cross E. The effects of a cancer nutrition education program on sixth grade students. School Food Service Research Review. 1989;13(2):124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Callister R, Collins CE. Effects of integrating pedometers, parental materials, and E-mail support within an extracurricular school sport intervention. J Adolesc Heal. 2009;44(2):176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie J, Dixon LB, Smiciklas-Wright H, Mitchell D, Shannon B, Tershakovec A. Change in nutrient intakes, number of servings, and contributions of total fat from food groups in 4- to 10-year-old children enrolled in a nutrition education study. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:865–873. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihas C, Mariolis A, Manios Y, Naska A, Arapaki A, Mariolis-Sapsakos T, Tountas Y. Evaluation of a nutrition intervention in adolescents of an urban area in Greece: short- and long-term effects of the VYRONAS study. Public Health Nutrition. 2010;13(5):712–719. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick K, Calfas KJ, Norman GJ, Zabinski MF, Sallis JF, Rupp J, Covin J, Cella J. Randomized controlled trial of a primary care and home-based intervention for physical activity and nutrition behaviors: PACE + for adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160(2):128–136. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick K, Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Lydston DD, Calfas KJ, Zabinski MF, Wilfley DE, Saelens BE, Brown DR. A multicomponent program for nutrition and physical activity change in primary care: PACE + for adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155(8):940–946. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.8.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson N, Atkin AJ, Biddle SJ, Gorely T. A family-based intervention to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in adolescents: a pilot study. Public Health Nutrition. 2010;13(6):876–885. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queral C. The impact of a Nutrition Education Program on Nutrition Knowledge and Attitudes, as well as Food Selection, in a Cohort of Migrant and Seasonal Farm Worker Children. United States: Touro University International; 2007. p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg DE, Norman GJ, Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Patrick K. Covariation of adolescent physical activity and dietary behaviors over 12 months. J Adolesc Heal. 2007;41(5):472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story M, Sherwood NE, Himes JH, Davis M, Jacobs DR Jr, Cartwright Y, Smyth M, Rochon J. An after-school obesity prevention program for African-American girls: the Minnesota GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(1 Suppl 1):S54–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talvia S, Rasanen L, Lagstrom H, Pahkala K, Viikari J, Ronnemaa T, Arffman M, Simell O. Longitudinal trends in consumption of vegetables and fruit in Finnish children in an atherosclerosis prevention study (STRIP) Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(2):172–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Cooke LJ, Gibson EL, Sapochnik M, Sheiham A, Lawson M. Increasing children's acceptance of vegetables; a randomized trial of parent-led exposure. Appetite. 2003;40(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6663(02)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JM, Henry CJK, Lightowler HJ, Bradshaw SM, Perwaiz S. Evaluation of a pilot school programme aimed at the prevention of obesity in children. Heal Promot Int. 2003;18(4):287–296. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dag402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werch C, Bian H, Carlson J, Moore M, DiClemente C, Huang I, Ames S, Thombs D, Weiler R, Pokorny S. Brief integrative multiple behavior intervention effects and mediators for adolescents. J Behav Med. 2011;34(1):3–12. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9281-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auld GW, Romaniello C, Heimendinger J, Hambidge C, Hambidge M. Outcomes from a school-based nutrition education program using resource teachers and cross-disciplinary models - Duplicate of Ref ID 90062. J Nutr Educ. 1998;30(5):268–280. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(98)70336-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates NJ. An Evaluation of a Stage of Change Nutrition Intervention in Latino Families with Young Children. United States: University of Illinois at Chicago, Health Sciences Center, School of Public Health; 2001. p. 353. [Google Scholar]

- Bell CG, Lamb MW. Nutrition education and dietary behavior of fifth graders. J Nutr Educ. 1973;5:196–199. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(73)80086-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boaz A, Ziebland S, Wyke S, Walker J. A 'five-a-day' fruit and vegetable pack for primary school children. Part II: controlled evaluation in two Scottish schools. Heal Educ J. 1998;57(2):105–116. doi: 10.1177/001789699805700203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cade J, Lambert H. Evaluation of the effect of the removal of the family income supplement (FIS) free school meal on the food intake of secondary schoolchildren. J Public Health Med. 1991;13(4):295–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casazza K. A Computer Based Approach to Improve the Dietary and Physical Activity Patterns of a Diverse Group of Adolescents. United States: Florida International University; 2006. p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- Craven K, Moore J, Swart A, Keene A, Kolasa K. School-based nutrition education intervention: effect on achieving a healthy weight among overweight ninth-grade students. J Public Health Manag Pract JPHMP. 2011;17(2):141–146. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181df0db4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covelli MM. PhD thesis. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL; 2000. Efficacy of a School-Based Intervention on Blood Pressure and Cortisol Levels of African American Adolescents; p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KW, Watson K, Baranowski T, Baranowski JH, Zakeri I. Squire's quest: intervention changes occurred at lunch and snack meals. Appetite. 2005;45(2):148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KW, Zakeri I. Fruits, vegetables, milk, and sweetened beverages consumption and access to a la carte/snack bar meals at school. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):463–467. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.3.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S, Petticrew M, Higgins C, Findlay A, Sparks L. Large scale food retailing as an intervention for diet and health: quasi-experimental evaluation of a natural experiment. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(12):1035–1040. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day LL, Rodriguez EC. Impact of a field trip to a health museum on children's health-related behaviors and perceived control over illness. Am J Heal Educ. 2002;33(2):94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Di Noia J, Contento IR, Prochaska JO. Computer-mediated intervention tailored on transtheoretical model stages and processes of change increases fruit and vegetable consumption among urban African-American adolescents. Am J Health Promot AJHP. 2008;22(5):336–341. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.5.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CS, Hermann JR. Piloting a cooperative extension service nutrition education program on first-grade children's willingness to try foods containing legumes. J Ext. 2011;49(1):Article 1IAW3. (Epublication) [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen K, HaraldsdC³ttir J, Pederson R, Flyger HV. Effect of a fruit and vegetable subscription in Danish schools. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6(1):57–63. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlman MM, Dake JA, McCaughtry N, Martin J. A pilot study to examine the effects of a nutrition intervention on nutrition knowledge, behaviors, and efficacy expectations in middle school children. J Sch Heal. 2008;78(4):216–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerster SB, Gregson J, Beall DL, Hudes M, Magnuson H, Livingston S, Davis MA, Joy ABJ, Garbolino T. The California children's 5 a Day Power Play! Campaign: evaluation of a large-scale social marketing initiative. Fam Commun Health. 1998;21(1):46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Friel S, Kelleher C, Campbell P, Nolan G. Evaluation of the Nutrition Education at Primary School (NEAPS) programme. Public Health Nutr. 1999;2(4):549–555. doi: 10.1017/s1368980099000737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou C. The Effect of Nutrition Education on Third Graders' School Lunch Consumption in a School Offering Food Pyramid Choice Menus. Oregon: Oregon State Department of Education, Salem.Child Nutrition Division; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gortmaker SL, Cheung LWY, Peterson KE, Chomitz G, Cradle JH, Dart H, Fox MK, Bullock RB, Sobol AM, Colditz G, Field AE, Laird N. Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children: eat well and keep moving. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(9):975–983. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosliner WA, James P, Yancey AK, Ritchie L, Studer N, Crawford PB. Impact of a worksite wellness program on the nutrition and physical activity environment of child care centers. Am J Health Promot AJHP. 2010;24(3):186–189. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.08022719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble LS, Falciglia G, Davis AM, Couch SC. A curriculum based on social learning theory emphasizing fruit exposure and positive parent child-feeding strategies: a pilot study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(1):100–103. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy HM, Williams KE, Camise TS. Kid's Choice Program improves weight management behaviors and weight status in school children. Appetite. 2011;56(2):484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott J, Wiesmann D. In: The Impact of Conditional cash Transfer Programs on Food Consumption in Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua. Adato M, Hoddinott J, editor. Edited by Adato M, Hoddinott J. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hollar D, Messiah SE, Lopez-Mitnik G, Hollar TL, Almon M, Agatston AS. Healthier options for public schoolchildren program improves weight and blood pressure in 6- to 13-year-olds. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(2):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne PJ, Tapper K, Lowe CF, Hardman CA, Jackson MC, Woolner J. Increasing children's fruit and vegetable consumption: a peer-modelling and rewards-based intervention. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(12):1649–1660. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T. Evaluation of Food and Fun for Everyone: A Nutrition Education Program for Third and Fourth Grade Students. United States: Oklahoma State University; 2009. p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Jamelske E, Bica LA, McCarty DJ, Meinen A. Preliminary findings from an evaluation of the USDA fresh fruit and vegetable program in Wisconsin schools. Wis Med J. 2008;107(5):225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez MM, Receveur O, Trifonopoulos M, Kuhnlein H, Paradis G, Macaulay AC. Comparison of the dietary intakes of two different groups of children (grades 4 to 6) before and after the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(9):1191–1194. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(03)00980-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelder S, Hoelscher DM, Barroso CS, Walker JL, Cribb P, Hu S. The CATCH Kids Club: a pilot after-school study for improving elementary students' nutrition and physical activity. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(2):133–140. doi: 10.1079/phn2004678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liquori T, Koch PD, Contento IR, Castle J. The cookshop program: outcome evaluation of a nutrition education program linking lunchroom food experiences with classroom cooking experiences. J Nutr Educ. 1998;30(5):302–313. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(98)70339-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long JD. PhD thesis. University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX; 2001. The Effects of a School-Based Nutrition Education Intervention on self-efficacy for Healthy Eating, Usual Food Choices, Dietary Knowledge, and Fruit, Vegetable, and Fat Consumption in Adolescents; p. 202. [Google Scholar]

- Long JD, Stevens KR. Using technology to promote self-efficacy for healthy eating in adolescents. J Nurs Scholarsh Off Publ Sigma Theta Tau Int Honor Soc Nurs Sigma Theta Tau. 2004;36(2):134–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manios Y, Moschandreas J, Hatzis C, Kafatos A. Health and nutrition education in primary schools of Crete: changes in chronic disease risk factors following a 6-year intervention programme. B J Nutr. 2002;88:315–324. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matvienko O. Impact of a nutrition education curriculum on snack choices of children ages six and seven years. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(5):281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAleese JD, Rankin LL. Garden-based nutrition education affects fruit and vegetable consumption in sixth-grade adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(4):662–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan PJ, Warren JM, Lubans DR, Saunders KL, Quick GI, Collins CE. The impact of nutrition education with and without a school garden on knowledge, vegetable intake and preferences and quality of school life among primary-school students. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(11):1931–1940. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvera N, Bush JA, Sharma SV, Knox B, Scherer RL, Butte NF. BOUNCE: a community-based mother-daughter healthy lifestyle intervention for low-income Latino families. Obesity. 2010;18(Suppl 1):S102–S104. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CL, Zauner M, Oakes JM, Taylor G, Bishop DB. Evaluation of a theater production about eating behavior of children. J Sch Heal. 2002;72(6):256–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb07339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunatha Rao D, Vijayapushpam T, Subba Rao GM, Antony GM, Sarma KVR. Dietary habits and effect of two different educational tools on nutrition knowledge of school going adolescent girls in Hyderabad, India. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61(9):1081–1085. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe MM, Merrigan KA, Rogers BL, Goldberg JP. The effects of school garden experiences on middle school-aged students' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors associated with vegetable consumption. Heal Promot Pract. 2011;12(1):36–43. doi: 10.1177/1524839909349182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ CR, Tate DF, Whiteley JA, Winett RA, Winett SG, Pfleger J. The effects of an innovative WWW-based health behavior program on the nutritional practices of tenth grade girls: preliminary report on the Eat4Life Program. J Gend Cult Heal. 1998;3(2):121–128. doi: 10.1023/A:1023234515776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schagen S, Blenkinsop S, Schagen I, Scott E, Teeman D, White G, Ransley J, Cade J, Greenwood D. Evaluation of the School Fruit and Vegetable Pilot Scheme: final report. Big Lottery Fund: University of Leeds; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MB. The influence of a verbal prompt on school lunch fruit consumption: A pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4(6): . doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-6. (Epublication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Hamre R, Dietz WH, Wasserman RC, Slora EJ, Myers EF, Sullivan S, Rockett H, Thoma KA, Dumitru G, Resnicow KA. Office-based motivational interviewing to prevent childhood obesity - A feasibility study. Arch Pediat Adolesc Med. 2007;161(5):495–501. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon B, Graves K, Hart M. Food behavior of elementary school students after receiving nutrition education. J Am Diet Assoc. 1982;81(4):428–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Parcel GS, Baranowski T, Forthofer R, O'Hara NM. Promoting physical activity and a healthful diet among children: results of a school-based intervention study. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(8):986–991. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.81.8.986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal N, Misra A, Shah P, Gulati S. Effects of controlled school-based multi-component model of nutrition and lifestyle interventions on behavior modification, anthropometry and metabolic risk profile of urban Asian Indian adolescents in North India. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(4):364–373. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A, Duhe S, Evans A, Condrasky M. Using student-produced media to promote healthy eating - A pilot study on the effects of a media and nutrition intervention. Sci Commun. 2008;30(1):108–125. doi: 10.1177/1075547008319435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tak NI, te Velde SJ, Brug J. Long-term effects of the Dutch Schoolgruiten Project–promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among primary-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(8):1213–1223. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ICDS, Sichieri R, Sandre-Pereira G, da Veiga GV. Evaluation of an obesity prevention program in adolescents of public schools. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(1):59–68. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102011000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JL. The Relationship of Parent and Child Food Choices: Influences of a Supermarket Intervention. United States: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; 1991. p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CM, Dannhauser A, Joubert G. Impact of a nutrition education programme on nutrition knowledge and dietary practices of lower socioeconomic communities in the Free State and Northern Cape. South Afr J Clin Nutr. 2003;16(3):89–95. [Google Scholar]

- White G. Evaluation of the school fruit and vegetable pilot scheme. Educ Heal. 2006;24(4):62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JE. Social Support and Adolescent Nutrition Behaviors in African-American Families. United States: University of South Carolina; 2004. p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Agozzino E, Esposito D, Genovese S, Manzi E, Russo Krauss P. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a nutrition education intervention performed by primary school teachers. Ital J Public Health. 2007;4(4):131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Ashfield-Watt P, Stewart EA, Scheffer JA. A pilot study of the effect of providing daily free fruit to primary-school children in Auckland, New Zealand. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(5):693–701. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro S, Viggiano A, Di Costanzo A, Madeo I, Baccari ME, Marchitelli E, Raia M, Viggiano E, Deepak S, Monda M, De Luca B. Kaledo, a new educational board-game, gives nutritional rudiments and encourages healthy eating in children: a pilot cluster randomized trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165(9):630–635. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A, Hetherington M, Adamson A, Porteous LEG, Higgins C, Foster E. The Development and Evaluation of a Novel School Based Intervention to Increase Fruit and Vegetable Intake in Children. London: Food Standards Agency; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AS, Porteous LE, Foster E, Higgins C, Stead M, Hetherington M, Ha MA, Adamson AJ. The impact of a school-based nutrition education intervention on dietary intake and cognitive and attitudinal variables relating to fruits and vegetables. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(6):650–656. doi: 10.1079/phn2004721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelopoulos PD, Milionis HJ, Grammatikaki E, Moschonis G, Manios Y. Changes in BMI and blood pressure after a school based intervention: the CHILDREN study. Eur J Public Health. 2009;19(3):319–325. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ask AS, Hernes S, Aarek I, Vik F, Brodahl C, Haugen M. Serving of free school lunch to secondary-school pupils - a pilot study with health implications. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(2):238–244. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009990772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auld GW, Romaniello C, Heimendinger J, Hambidge C, Hambidge M. Outcomes from a school-based nutrition education program alternating special resource teachers and classroom teachers. J Sch Heal. 1999;69(10):403–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1999.tb06358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Cullen KW, DeMoor C, Rittenberry L, Hebert D. 5 a day achievement badge for African-American Boy Scouts: pilot outcome results. Prev Med. 2002;34(3):353–363. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Cullen KW, Marsh T, Islam N, Zakeri I, Honess-Morreale L, DeMoor C. Squire's Quest! Dietary outcome evaluation of a multimedia game. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(1):52–61. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Davis M, Resnicow K, Baranowski J, Doyle C, Lin LS, Smith M, Wang DT. Gimme 5 fruit, juice, and vegetables for fun and health: outcome evaluation. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2000;27(1):96–111. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates HM. Promoting Healthy Eating and Active Living in Schools: A Pilot Study. Canada: University of Alberta; 2010. p. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Bere E. Fruits and Vegetables make the Mark. Oslo: Institute for Research, University of Oslo; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bere E, Veierod MB, Bjelland M, Klepp KI. Outcome and process evaluation of a Norwegian school-randomized fruit and vegetable intervention: Fruits and Vegetables Make the Marks (FVMM) Heal Educ Res. 2006;21(2):258–267. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bere E, Veierod MB, Klepp KI. The Norwegian School Fruit Programme: evaluating paid vs. no-cost subscriptions. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bere E, Veierod MB, Klepp KI. Free school fruit - Sustained effect three years later. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4(1):5–10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum AS, Lytle LA, Story M, Perry CL, Murray DM. Are differences in exposure to a multicomponent school-based intervention associated with varying dietary outcomes in adolescents? Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2002;29(4):427–443. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom-Hoffman J, Kelleher C, Power TJ, Leff SS. Promoting healthy food consumption among young children: evaluation of a multi-component nutrition education program. J Sch Psychol. 2004;42(1):45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2003.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blom-Hoffman J, Wilcox KR, Dunn L, Leff SS, Power TJ. Family involvement in school-base health promotion: bringing nutrition information home. Sch Psychol Rev. 2008;37(4):567–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd-Bredbenner C, O'Connell LH, Shannon B. Junior high home economics curriculum: its effect on students' knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Home Econ Res J. 1982;11(2):123–133. doi: 10.1177/1077727X8201100202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coates TJ, Barofsky I, Saylor KE. Modifying the snack food consumption patterns of inner city high school students: the Great Sensations study. Prev Med. 1985;14(2):234–247. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(85)90039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contento IR, Koch PA, Lee H, Calabrese-Barton A. Adolescents demonstrate improvement in obesity risk behaviors after completion of choice, control & change, a curriculum addressing personal agency and autonomous motivation. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(12):1830–1839. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke LJ, Chambers LC, Anez EV, Croker HA, Boniface D, Yeomans MR, Wardle J. Eating for pleasure or profit: the effect of incentives on children's enjoyment of vegetables. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(2):190–196. doi: 10.1177/0956797610394662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett SJ, Mullis R, Perry CL, Luepker RV. Parent education in youth-directed nutrition interventions. Prev Med. 1989;18(4):475–491. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(89)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KW, Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS. Girl Scouting: an effective channel for nutrition education. J Nutr Educ. 1997;29(2):86–91. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(97)70160-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KW, Smalling A, Thompson D, Watson KB, Reed D, Konzelmann K. Creating healthful home food environments: results of a study with participants in the expanded food and nutrition education program. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(6):380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day ME, Strange KS, McKay HA, Naylor P. Action schools! BC – healthy eating: effects of a whole-school model to modifying eating behaviours of elementary school children. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(4):328–331. doi: 10.1007/BF03403766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domel SB, Baranowski T, Davis H, Thompson WO, Leonard SB, Riley P, Baranowski J, Dudovitz B, Smyth M. Development and evaluation of a school intervention to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among 4th and 5th grade students. J Nutr Educ. 1993;25(6):345–349. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(12)80224-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Welk G, Hill J, Milliken G, Karteroliotis K, Johnston JA. Healthy youth places: A randomized controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of facilitating adult and youth leaders to promote physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption in middle schools. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2009;36(3):583–600. doi: 10.1177/1090198108314619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatohy IM, Mounir GM, Mahdy NH, El-Deghedi BM. Improving students' knowledge, attitude and practice towards cancer prevention through a health education program. Part II. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1998;73(5–6):755–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerster SB, Gregson J. The California Children's 5 a Day Power Play! Campaign: Evaluation Study of Activities in the School Channel. Sacremento: California Department of Health Services and California Public Health Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty AW, Antoniak M, Venn AJ, Davies L, Goodwin A, Salfield N, Stocks J, Britton J, Lewis SA. Does participation in a population-based dietary intervention scheme have a lasting impact on fruit intake in young children? Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(5):1080–1085. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster GD, Sherman S, Borradaile KE, Grundy KM, Vander Veur SS, Nachmani J, Karpyn A, Kumanyika S, Shults J. A policy-based school intervention to prevent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e794–e802. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, French SA, Story M, Nelson H, Hannan PJ. Promotions to increase lower-fat food choices among students in secondary schools: description and outcomes of TACOS (Trying Alternative Cafeteria Options in Schools) Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(5):665–674. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile DA, Welk G, Eisenmann JC, Reimer RA, Walsh DA, Russell DW, Callahan R, Walsh M, Strickland S, Fritz K. Evaluation of a multiple ecological level child obesity prevention program: Switch what you Do, View, and Chew. BMC Med. 2009;7:49. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-49. 1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German MJ, Pearce J, Wyse BW, Hansen RG. A nutrition component for high school health education curriculums. J Sch Heal. 1981;51(3):149–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1981.tb02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Dixit S, Fox MK, Laird N. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(4):409–418. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govula C. Culturally Appropriate Nutrition Lessons Increased Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in American Indian Children. United States: South Dakota State University; 2007. p. 54. [Google Scholar]