Abstract

Grand fir (Abies grandis Lindl.) has been developed as a model system for the study of wound-induced oleoresinosis in conifers as a response to insect attack. Oleoresin is a roughly equal mixture of turpentine (85% monoterpenes [C10] and 15% sesquiterpenes [C15]) and rosin (diterpene [C20] resin acids) that acts to seal wounds and is toxic to both invading insects and their pathogenic fungal symbionts. The dynamic regulation of wound-induced oleoresin formation was studied over 29 d at the enzyme level by in vitro assay of the three classes of synthases directly responsible for the formation of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes from the corresponding C10, C15, and C20 prenyl diphosphate precursors, and at the gene level by RNA-blot hybridization using terpene synthase class-directed DNA probes. In overall appearance, the shapes of the time-course curves for all classes of synthase activities are similar, suggesting coordinate formation of all of the terpenoid types. However, closer inspection indicates that the monoterpene synthases arise earlier, as shown by an abbreviated time course over 6 to 48 h. RNA-blot analyses indicated that the genes for all three classes of enzymes are transcriptionally activated in response to wounding, with the monoterpene synthases up-regulated first (transcripts detectable 2 h after wounding), in agreement with the results of cell-free assays of monoterpene synthase activity, followed by the coordinately regulated sesquiterpene synthases and diterpene synthases (transcription beginning on d 3–4). The differential timing in the production of oleoresin components of this defense response is consistent with the immediate formation of monoterpenes to act as insect toxins and their later generation at solvent levels for the mobilization of resin acids responsible for wound sealing.

Many conifer species respond to bark beetle invasion by secreting oleoresin (pitch) at the attack sites (Johnson and Croteau, 1987; Raffa, 1991; Nebeker et al., 1993). This defensive secretion is composed of roughly equal amounts of turpentine (largely a mixture of monoterpenes [C10] with some sesquiterpenes [C15]) and rosin (diterpene [C20] resin acids). Oleoresin seals wounds and is toxic to both invading insects and their associated fungal pathogens (Croteau and Johnson, 1985; Raffa et al., 1985). Constitutive oleoresin is accumulated in specialized secretory structures of the stem, such as resin ducts and blisters, whereas induced oleoresin originates in nonspecialized cells adjacent to the site of injury (Cheniclet, 1987; Fahn, 1988; Raffa, 1991; Blanchette, 1992; Yamada, 1992). That both constitutive and localized, inducible terpenoid-based defense mechanisms seem to have been selected in this ancient and highly adaptable group of plants is unusual.

A number of inducible terpenoid defensive compounds (phytoalexins) from angiosperm species are well known (Stoessl et al., 1976; Threlfall and Whitehead, 1991). These include both sesquiterpenoid types (Facchini and Chappell, 1992; Zook et al., 1992; Back and Chappell, 1995; Chen et al., 1995) and diterpenoid types (West et al., 1989; Mau and West, 1994). Like phytoalexin production, induced oleoresinosis in conifers resembles a phase 2 plant-defense response (Hahlbrock et al., 1995) in that it is localized to the wound site and is proportional in amount to the severity of the wound (Lewinsohn et al., 1991a). However, it differs in a number of features. Unlike phytoalexin production, oleoresin is synthesized constitutively in significant amounts (Lewinsohn et al., 1991b), the wound response requires a much longer time to reach maximum (7–14 d) (Gijzen et al., 1992), and, in addition to antibiosis, oleoresin plays an important role in wound sealing by the solidification of resin acids following the evaporation of turpentine (Croteau and Johnson, 1985). Most significantly, oleoresinosis involves the coordinated production of three distinct classes of terpenoids: monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes.

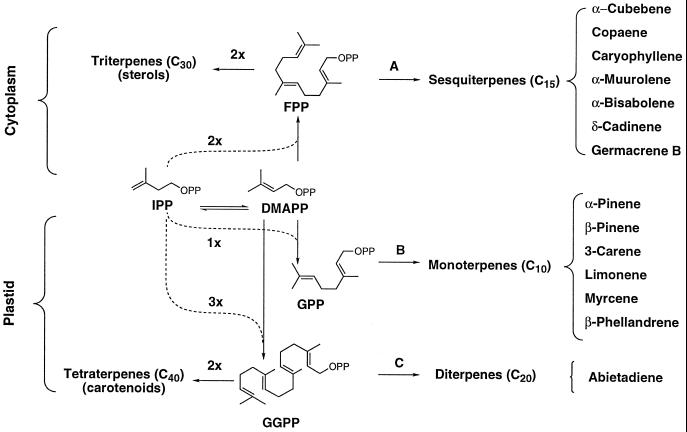

Grand fir (Abies grandis Lindl.) has been developed as a model system for the study of induced oleoresin production in conifers. The monoterpene fraction (85%) and the sesquiterpene fraction (15%) of grand fir stem turpentine consists of very complex mixtures of olefins formed directly from geranyl diphosphate and farnesyl diphosphate by the action of plastidial monoterpene synthases and cytosolic sesquiterpene synthases, respectively (Lewinsohn et al., 1992; Gershenzon and Croteau, 1993; Chappell, 1995; McGarvey and Croteau, 1995). The diterpene fraction (approximately 20% of total resin by weight in grand fir [Lewinsohn et al., 1993b]) is comprised largely of abietic acid derived by oxidative modification of the olefin abietadiene, which is formed by cyclization of geranylgeranyl diphosphate in plastids (Funk and Croteau, 1994; LaFever et al., 1994) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Organization of terpenoid biosynthesis from isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) via dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), geranyl diphosphate (GPP), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP). The reactions catalyzed by sesquiterpene synthases (A), monoterpene synthases (B), and diterpene synthases (C) are indicated, and the major products of the monoterpene, sesquiterpene, and diterpene pathways that constitute the oleoresin of grand fir are listed.

Preliminary studies based on in vitro enzyme assays have suggested that monoterpene and diterpene resin acid biosynthesis in grand fir are coordinately induced upon wounding, and investigations based on immunoblotting have indicated that the increase in monoterpene synthase activity in stem tissue is proportional to the increase in enzyme protein in the induced response (Gijzen et al., 1992; Funk et al., 1994). The lack of molecular tools has thus far prevented examination of oleoresinosis at the level of gene expression.

Recently, a cDNA encoding the principal diterpene synthase of grand fir, abietadiene synthase, was isolated (Stofer Vogel et al., 1996). Also recently isolated from this species were two cDNA clones encoding sesquiterpene synthases (Steele et al., 1998) and three encoding monoterpene synthases, including (−)-pinene synthase, which produces both (−)-α- and (−)-β-pinene (Bohlmann et al., 1997). In this paper, we describe induced oleoresinosis at the level of steady-state transcript abundances for the three relevant classes of terpene synthases that produce oleoresin in grand fir.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials, Substrates, and Reagents

Two-year-old grand fir (Abies grandis Lindl.) saplings were purchased (Silver Seed Co., Roy, WA) and grown as previously described (Lewinsohn et al., 1991b). The source of seed was the Sears Creek area of the south fork of the Clearwater River drainage near Harpster, Idaho, elevation 1.1 to 1.4 km, which provides much of the material for grand fir replantation in the Pacific northwest. The saplings were grown for at least 6 weeks past bud break to minimize the influence of flushing on induced oleoresinosis (Steele et al., 1995), and were grouped into uniform size populations to minimize developmental variation within experiments. Saplings used for the daily time-course experiments ranged in height from 10 to 36 cm, with an average of 15 cm, whereas the population used for the hourly time-course experiments ranged in height from 7 to 12 cm, averaging about 9 cm.

The syntheses of [1-3H]geranyl diphosphate (250 Ci/mol) (Croteau et al., 1994), [1-3H]farnesyl diphosphate (125 Ci/mol) (Dehal and Croteau, 1988), and [1-3H]geranylgeranyl diphosphate (120 Ci/mol) (LaFever et al., 1994) have been described previously. [α-32P]dATP (3000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from DuPont/NEN, and dNTPs were purchased from Gibco-BRL. Hepes, Tris, Mops, and 2-Mercaptoethanol were purchased from Research Organics (Cleveland, OH), and thiourea was purchased from Aldrich. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise specified.

Stem Wounding and Enzyme and RNA Extraction

For the daily time-course experiments, eight saplings were wounded for each day, and a time point consisted of trees from 2 d combined (16 total). For hourly time-course experiments, 10 saplings were wounded for each time point. Saplings were wounded with a razor blade using a standard protocol (Gijzen et al., 1991), approximately every 3 mm along the entire stem on opposite sides. At the appropriate times, saplings were harvested, the primary growth was removed, and the stem was cut into 4- to 6-cm segments and frozen in liquid N2. After removing any needles, the frozen stem sections were ground to a powder using a chilled no. 1 Wiley mill (Thomas Scientific).

For enzyme extraction (Lewinsohn et al., 1991a), a small portion of the still-frozen powder (approximately 1.0 g) was added to a 50-mL conical tube containing 30 mL of chilled protein-extraction buffer (50 mm Hepes, pH 7.3, 20 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% [w/v] glycerol, and 1% [w/v] each PVP and PVPP). This preparation was mixed on ice for 30 min and then clarified by centrifugation at 5000g for 20 min. Aliquots of the supernatant were then assayed independently for monoterpene, sesquiterpene, and diterpene synthase activity. Protein concentration of the extract was determined by the Bradford (1976) method using the Bio-Rad procedure with BSA as a standard.

For RNA extraction the remaining powder (approximately 50 g) was added to a 1-L centrifuge bottle containing 175 mL of chilled RNA-extraction buffer (200 mm Tris, pH 8.5, 300 mm LiCl, 10 mm DTT, 10 mm Na-EDTA, 5 mm thiourea, 1 mm aurintricarboxylic acid, and 1% [w/v] each PVP and PVPP) and was purified using a published protocol (Lewinsohn et al., 1994).

Enzyme Assays

For the monoterpene synthase assay (Gijzen et al., 1991), 0.1-mL aliquots of the enzyme extract in microcentrifuge tubes were adjusted to 100 mm KCl and 1.0 mm MnCl2 and then overlaid with 1 mL of hexane to trap volatile monoterpene products before initiation of the reaction by the addition of 20 μm [1-3H]geranyl diphosphate. For the sesquiterpene synthase assay (Steele et al., 1998), 0.4-mL aliquots of the enzyme extract in microcentrifuge tubes were adjusted to 10 mm MgCl2 before the addition of 20 μm [1-3H]farnesyl diphosphate to initiate the reaction.

For the diterpene synthase assay (LaFever et al., 1994), 0.5-mL aliquots of the enzyme preparation in 10-mL glass screw-capped tubes were adjusted to 2.5 mm MgCl2 and 25 μm MnCl2 before the addition of 20 μm [1-3H]geranylgeranyl diphosphate to initiate the reaction. All assays were incubated for 1 h at 31°C, and then the reaction was terminated by the addition of excess EDTA to chelate the divalent metal ion cofactor. The reaction products were next extracted with hexane, and the monoterpene and sesquiterpene olefin fractions were isolated by batch elution from silica gel (type 60Å, Mallinckrodt, Chesterfield, MO) for aliquot counting of tritium by liquid scintillation spectrometry (counting efficiency, 40%); diterpene olefins were similarly isolated by elution from MgSO4/silica gel before aliquot counting. Each assay was run in triplicate for each time point and the averaged values ± se are reported.

Radio-GLC analysis of labeled monoterpenes has been previously described (Croteau and Cane, 1985; Satterwhite and Croteau, 1988). For determining the level and distribution of monoterpene synthase activities in individual saplings, a recently developed, nondestructive sampling technique was employed along with a microscale assay method (Katoh and Croteau, 1997).

Terpene Synthase Class-Directed DNA Probe Construction and Evaluation

Class-directed probes for transcripts encoding either monoterpene, sesquiterpene, or diterpene synthases were designed based on comparison of the corresponding cDNA sequences for these enzymes. The probe for monoterpene synthases was based on the (−)-pinene synthase cDNA (bp 1372–1707) that represents one of the major inducible monoterpene synthases of grand fir (Bohlmann et al., 1997). The probe for sesquiterpene synthases was based on the δ-selinene synthase cDNA (bp 373–733) that represents one of two presently defined constitutive sesquiterpene synthases of grand fir (Steele et al., 1998), and the probe for diterpene synthases was based on the abietadiene synthase cDNA (bp 235–530) that represents the major (> 90%) constitutive and inducible diterpene synthase of this species (LaFever et al., 1994; Stofer Vogel et al., 1996).

The probes were generated via PCR with specific primers, separated on a low-melting-temperature agarose gel (Gibco-BRL), and purified using a gel nebulizer and Micropure separators (Amicon) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The monoterpene synthase probe was labeled using a random-priming protocol (Sambrook et al., 1989), except that the sequence-specific antisense primer was substituted for the hexamers. The sesquiterpene synthase and diterpene synthase probes used in RNA-blot hybridization were labeled via PCR according to the manufacturer's (Gibco-BRL) protocol. A cDNA insert encoding soybean (Glycine max) ubiquitin was labeled using random hexamers and was employed for monitoring constitutive gene expression.

Plasmid DNA slot-blot analyses were conducted to assess the class selectivity of the probes. The (−)-pinene synthase probe easily recognized the cDNAs encoding (−)-limonene synthase and myrcene synthase, with a signal strength 50 to 70% of that of the (−)-pinene synthase cDNA itself; (−)-pinene synthase, (−)-limonene synthase, and myrcene synthase represent three of the major inducible monoterpene synthases of grand fir from a family comprised of approximately five constitutive and six inducible forms (Gijzen et al., 1991; Bohlmann et al., 1997).

The (−)-pinene synthase probe did not cross-hybridize under these conditions with either of the cDNAs encoding the recently defined sesquiterpene synthases δ-selinene synthase and γ-humulene synthase (Steele et al., 1998), or with the cDNA representing the principal diterpene synthase of grand fir, abietadiene synthase (Stofer Vogel et al., 1996). In similar fashion, the sesquiterpene synthase probe based on δ-selinene synthase efficiently recorded the cDNA encoding γ-humulene synthase (comparative signal strength > 50%), the only other presently defined, constitutive sesquiterpene synthase of grand fir, which contains at least six constitutive and two inducible sesquiterpene synthases (Steele et al., 1998). The δ-selinene synthase-based probe did not cross-hybridize with any of the three cDNAs encoding monoterpene synthases of grand fir or the cDNA encoding abietadiene synthase. Finally, the diterpene synthase probe based on abietadiene synthase did not detectably hybridize with any of the three cDNAs encoding monoterpene synthases or the two cDNAs encoding sesquiterpene synthases. Thus, given the limited number of target genes now available from grand fir for testing, the probes do appear to be selective for the respective terpene synthase classes.

RNA Blotting and Analysis

Total RNA was separated under denaturing conditions using formaldehyde in a 1.2% agarose gel and was transferred by capillary action to nitrocellulose (Optitran, Schleicher & Schuell) using standard protocols (Ausubel et al., 1991). The hybridization buffer consisted of 6× SSPE, 2× Denhardt's solution, 0.5% SDS, and 100 mm EDTA at 65°C, and the blots were washed using 3× SSPE and 0.5% SDS at 65°C. The resulting labeled blots were exposed to an imaging screen (Bio-Rad) and analyzed with a molecular imaging system (GS-525 system and Molecular Analyst software, version 2.1, Bio-Rad). Following analysis, each of the three separate blots (for monoterpene, sesquiterpene, and diterpene synthases) was stripped and reprobed with the soybean ubiquitin cDNA as a constitutively expressed gene marker to correct for loading and blotting variations between samples.

RESULTS

Wound-Induced Terpenoid Synthesis

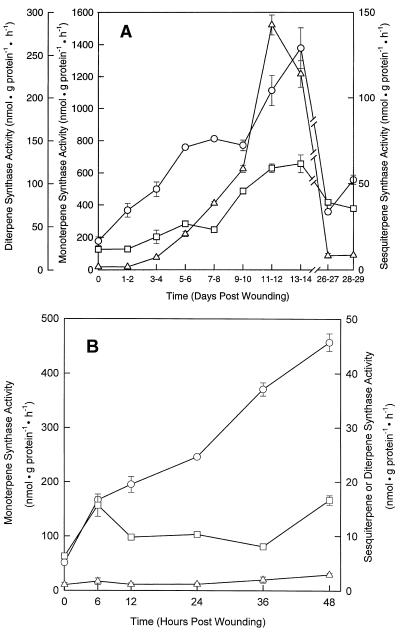

The capacity for monoterpene, sesquiterpene, and diterpene biosynthesis in wounded grand fir was examined over a period of 4 weeks by cell-free assay of the corresponding monoterpene, sesquiterpene, and diterpene synthase activities in stem extracts. Upon wounding, all three classes of synthases appear to be induced with a roughly similar time course of increase (Fig. 2A). The monoterpene synthase activity exceeded the sesquiterpene and diterpene synthase activities by a factor of roughly 10 and 5, respectively; this higher apparent capacity for monoterpene biosynthesis has been observed previously and is reflective of the terpenoid distribution of the oleoresin.

Figure 2.

Changes in the activities of the synthase enzymes of oleoresin biosynthesis in grand fir sapling stems in response to wounding. Total enzyme activities for the monoterpene synthases (○), sesquiterpene synthases (□), and diterpene synthases (▵) are plotted as a function of time after wounding. Details of the assays for the daily (A) and hourly (B) time courses are provided in Methods. Assays were performed in triplicate and the data are reported as means ± se. Where error bars are not indicated, the range lies within the symbol.

The relative activity ratios of the different types of terpenoid synthases are known to vary somewhat with the genetic background, age, and physiological condition of the sapling (Lewinsohn et al., 1993a; Steele et al., 1995). A study of the quantitative and qualitative variation in the monoterpene synthase activities of grand fir was recently completed and seven chemotypes were defined (Katoh and Croteau, 1997). The monoterpene synthase activities also show a faster initial response to wounding, with a 2-fold increase on d 1 to 2, when no detectable change is observable for the sesquiterpene or diterpene synthases.

This more rapid response in monoterpene biosynthesis has appeared in previous time-course studies (Lewinsohn et al., 1991a; Gijzen et al., 1992; Funk et al., 1994), but was never examined further to our knowledge. Therefore, a second, abbreviated time-course analysis was carried out over a 2-d period (Fig. 2B). The monoterpene synthase activities increased 3-fold by 6 h after wounding and showed about a 10-fold increase by 48 h after wounding (these higher differences compared with the initial time course are the result of differences in the zero-time controls; the absolute activity levels are comparable). The sesquiterpene synthase and diterpene synthase activities showed very little change during this period.

Radio-GLC analysis of the monoterpenes produced by the induced synthases 24 h (principally limonene) and 7 d (primarily α- and β-pinene) after wounding a set of 10 saplings using a recently developed protocol (Katoh and Croteau, 1997) suggested the immediate up-regulation of a constitutive activity for the production of 1 of the more repellent and toxic of the monoterpenes (Bordasch and Berryman, 1977; Raffa et al., 1985). This was followed later by an increase in those monoterpenes (pinenes) most notable for their solvent properties in dissolving resin acids (Kelly and Rohl, 1989). This indicates that at least two different monoterpene synthase genes are modulated during this time interval.

Wound-Induced Terpenoid Synthase Genes

The regulation of terpenoid synthase gene expression was examined by RNA-blot analysis of total RNA isolated from the same grand fir saplings employed in the above time-course experiments. To examine expression of each class of terpenoid synthase, DNA probes were designed from the appropriate coding regions to hybridize to RNAs for monoterpene, sesquiterpene, or diterpene synthases. Evaluation of the probes by plasmid DNA slot-blot analysis (data not shown) showed that the probes did cross-hybridize between gene types within each synthase class (e.g. the pinene synthase probe to the similarly induced limonene synthase), but did not cross-hybridize between representatives of the other gene classes (e.g. the monoterpene synthase probe to either sesquiterpene or diterpene synthases).

Traditionally, gene-specific probes are constructed based on 3′-untranslated sequences, but this approach was not feasible in the present case (for class-selective probes) because several of the monoterpene synthase (Bohlmann et al., 1997) and sesquiterpene synthase (Steele et al., 1998) cDNA isolates had divergent 3′-untranslated regions but were 99% identical in the respective coding sequence.

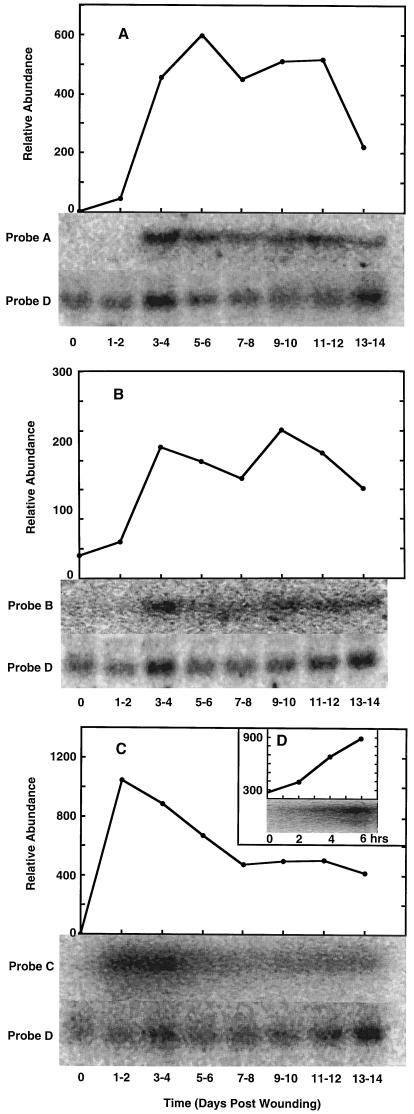

Although no cross-hybridization was observed between gene classes, a complete set of terpene synthase sequences is not yet available, so the selectivity of the probes cannot be determined with certainty. However, RNA-blot analysis (Fig. 3, A and B) using the sesquiterpene and diterpene synthase-selective probes suggested the coordinated regulation of induced biosynthesis of these two terpenoid classes, with corresponding mRNA accumulation beginning at d 3 to 4, followed by a rise to a constant steady-state level through d 11 to 12, and then a decline that returned to background levels by d 29 (data not shown). However, consistent with the time course of the change in monoterpene synthase activities, the monoterpene synthase genes are not regulated in concert with the sesquiterpene and diterpene synthase genes. The respective mRNA transcripts accumulate more rapidly, peaking at d 1 to 2 and declining steadily to about one-half-maximum before leveling off at d 7 to 8. This is followed by a final slow decline (Fig. 3C) and a return to background level by d 29 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Changes in terpenoid synthase mRNA steady-state levels in grand fir sapling stems in response to wounding. For each time point, total RNA was isolated, separated on an agarose gel (20 μg/lane), blotted, and hybridized to radiolabeled DNA probes directed toward diterpene synthases (A, Probe A), sesquiterpene synthases (B, Probe B), or monoterpene synthases (C and D, Probe C). The induction profile was normalized using a DNA probe specific for constitutively expressed ubiquitin (Probe D), and the RNA blots are illustrated by images digitized using a molecular imaging system (Bio-Rad).

To examine the rapidity of the monoterpene synthase response following wounding, an RNA blot from an abbreviated time course (2–6 h) was probed with the monoterpene synthase-directed DNA fragment. These results (Fig. 3D) indicated that the monoterpene synthase transcripts are detectable by 2 h after wounding, with a linear increase through 6 h. Since the control RNA blots (nonwounded stem) lacked detectable signal in all cases, it can be concluded that the apparent wound induction of all three classes of terpenoid synthases (for the formation of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes) represents primarily the transcriptional activation of the respective genes and immediate translation of the messages to the corresponding enzymes. Based on the activity time courses (Fig. 2) and on previous immunoblot analysis of the monoterpene synthases over this period (Gijzen et al., 1992), the terpene synthases appear to be stable.

DISCUSSION

Grand fir has been established as a model system for the study of wound-induced oleoresin formation in conifers (Lewinsohn et al., 1991a, 1993a, 1993b; Gijzen et al., 1992; Funk et al., 1994), a process that involves the biosynthesis of three families of terpenoids: monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes. The regulation of induced oleoresinosis was examined by monitoring changes in enzyme activity levels and steady-state transcript abundances for the monoterpene, sesquiterpene, and diterpene synthases over a 29-d time course following stem wounding.

The in vitro assays of synthase activity suggested that all three enzyme classes were induced, with the monoterpene synthases showing a faster response than the sesquiterpene and diterpene synthases, which increased more slowly in a coordinate manner (Fig. 2). Analysis of RNA blots for the same time course (Fig. 3) confirmed the differential regulation of the monoterpene synthases versus the sesquiterpene and diterpene synthases, and indicated that the onset of mRNA accumulation for each synthase class slightly precedes the increase in the corresponding enzyme activity, as expected. Furthermore, enzyme activity continued to rise beyond the point at which constant steady-state levels of message were reached (d 5–6 through 11–12), suggesting that the synthase proteins (as judged by activity) are stable in vivo.

The mRNA profile from an abbreviated time course (Fig. 3D) demonstrated that transcripts for monoterpene synthases were detectable as early as 2 h after stem wounding. The time frame for this early response is comparable to that of elicitor-induced terpenoid phytoalexin production (Facchini and Chappell, 1992; Back and Chappell, 1995; Chen et al., 1995). It is of interest to compare elicited phytoalexin formation in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) with wound-induced oleoresinosis in grand fir. In the former, induction of the sesquiterpene synthase required for phytoalexin biosynthesis is coordinated with the down-regulation of squalene synthase required for triterpene biosynthesis (Threlfall and Whitehead, 1988; Vögeli and Chappell, 1988), whereas in the latter, the production of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes is transcriptionally up-regulated (however, the timing for the induction of monoterpene synthase activity is earlier than for the other two terpenoid classes). Preliminary studies indicate that the complement of monoterpene synthases induced at the initial stage of the response (24 h) is different from that which appears later (7 d). This evidence and the current results suggest that two monoterpene synthase gene sets may exist, one induced early and the second induced late, possibly in coordination with the sesquiterpene and diterpene synthase genes.

The rapid induction of monoterpene biosynthesis, especially that of limonene, is consistent with the role of turpentine as a mix of toxins and antixenosis compounds, so the immediate deployment of this material in stem defense is easily rationalized. The duration of transcriptional activity for monoterpene synthase genes, accompanied by a continual increase in monoterpene synthase activity (especially for pinenes), is also consistent with the ultimate production of large amounts of turpentine required to solubilize and transport the diterpene resin acids to the wound site for the purpose of wound sealing (Croteau and Johnson, 1985; Johnson and Croteau, 1987). The differential regulation of monoterpene biosynthesis and diterpene biosynthesis can therefore also be rationalized.

The role(s) of the sesquiterpenes and the reason for delayed timing of sesquiterpene biosynthesis in the process of induced oleoresinosis are not as obvious. Wound-inducible sesquiterpene synthases produce E-α-bisabolene and δ-cadinene as major products (Steele et al., 1998). δ-Cadinene is the most widely distributed sesquiterpene in plants (Bordoloi et al., 1989) and serves as the precursor of a range of oxygenated phytoalexins in angiosperms (Stoessl et al., 1976; Threlfall and Whitehead, 1991), perhaps suggesting a role for conifer sesquiterpenes in antibiosis.

Oxygenated derivatives of δ-cadinene (torreyol) and bisabolene (atlantone) have been isolated from conifer resin, and both todomatuic acid (a bisabolane-type keto carboxylic acid) and its methyl ester (juvabione, the “paper factor” possessing insect juvenile hormone activity) have been identified in wood extracts of true fir (Abies) species (Norin, 1972). However, the slower timing of sesquiterpene biosynthesis would seem inconsistent with such a defense function in grand fir, unless this delay represents an adaptive strategy timed to coincide with the construction of egg galleries by the bark beetles, in this instance the fir engraver (Scolytis ventralis), or perhaps with spore germination (and thus increased vulnerability) of the pathogenic fungi vectored by the beetles (Berryman and Ashraf, 1970; Raffa et al., 1985; Gijzen et al., 1993; Nebeker et al., 1993). Conversion of the sesquiterpene olefins of grand fir to bioactive polyoxygenated metabolites could give a clearer indication of the potential defensive function of this family of oleoresin components. An investigation of this possibility is under way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eva Katahira for technical assistance, John Crock for helpful discussion, Thom Koehler for raising the trees, and Joyce Tamura-Brown for typing the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (NRI grant no. 97-35302-4432), by the Tode Foundation, and by project no. 0268 of the Agricultural Research Center, Washington State University, Pullman. J.B. is a Feodor Lynen Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Back K, Chappell J. Cloning and bacterial expression of a sesquiterpene cyclase from Hyoscyamus muticus and its molecular comparison to related terpene cyclases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7375–7381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryman AA, Ashraf M. Effects of Abies grandis resin on the attack behavior and brood survival of Scolytus ventralis (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) Can Entomol. 1970;102:1229–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette RA. Anatomical responses of xylem to injury and invasion by fungi. In: Blanchette RA, Biggs AR, editors. Defense Mechanisms of Woody Plants against Fungi. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann J, Steele CL, Croteau R. Monoterpene synthases from grand fir (Abies grandis): cDNA isolation, characterization and functional expression of myrcene synthase, (−)-4S-limonene synthase and (−)-(1S,5S)-pinene synthase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21784–21792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordasch RP, Berryman AA. Host resistance to the fir engraver beetle, Scolytus ventralis (Coleoptera:Scolytidae). 2. Repellency of Abies grandis resins and some monoterpenes. Can Entomol. 1977;109:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bordoloi M, Shukla VS, Nath SC, Sharma RP. Naturally occurring cadinenes. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:2007–2037. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of nanogram quantities of protein using the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell J. Biochemistry and molecular biology of the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Mol Biol. 1995;46:521–547. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X-Y, Chen Y, Heinstein P, Davisson VJ. Cloning, expression, and characterization of (+)-δ-cadinene synthase: a catalyst for cotton phytoalexin biosynthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;324:255–266. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheniclet C. Effects of wounding and fungus inoculation on terpene producing systems of maritime pine. J Exp Bot. 1987;38:1557–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Croteau R, Alonso WR, Koepp AE, Johnson MA. Biosynthesis of monoterpenes: partial purification, characterization, and mechanism of action of 1:8-cineole synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;309:184–192. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau R, Cane DE. Monoterpene and sesquiterpene cyclases. Methods Enzymol. 1985;110:383–405. [Google Scholar]

- Croteau R, Johnson MA. Biosynthesis of terpenoid wood extractives. In: Higuchi T, editor. Biosynthesis and Biodegradation of Wood Components. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 379–439. [Google Scholar]

- Dehal SS, Croteau R. Partial purification and characterization of two sesquiterpene cyclases from sage (Salvia officinalis) which catalyze the respective conversion of farnesyl pyrophosphate to humulene and caryophyllene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;261:346–356. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facchini PJ, Chappell J. Gene family for an elicitor-induced sesquiterpene cyclase in tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11088–11092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.11088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn A. Secretory tissues in vascular plants. New Phytol. 1988;108:229–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1988.tb04159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk C, Croteau R. Diterpenoid resin acid biosynthesis in conifers: characterization of two cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenases and an aldehyde dehydrogenase involved in abietic acid biosynthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;308:258–266. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk C, Lewinsohn E, Stofer Vogel B, Steele CL, Croteau R. Regulation of oleoresinosis in grand fir (Abies grandis). Coordinate induction of monoterpene and diterpene cyclases and two cytochrome P450-dependent diterpenoid hydroxylases by stem wounding. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:999–1005. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.3.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershenzon J, Croteau R (1993) Terpenoid biosynthesis: the basic pathway and formation of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes and diterpenes. In TS Moore Jr, ed, Lipid Metabolism in Plants. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 339–388

- Gijzen M, Lewinsohn E, Croteau R. Characterization of the constitutive and wound-inducible monoterpene cyclases of grand fir (Abies grandis) Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;289:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90471-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijzen M, Lewinsohn E, Croteau R. Antigenic cross-reactivity among monoterpene cyclases from grand fir and induction of these enzymes on stem wounding. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;294:670–674. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90740-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijzen M, Lewinsohn E, Savage TJ, Croteau RB. Conifer monoterpenes: biochemistry and bark beetle chemical ecology. In: Teranishi R, Buttery RG, Sugisawa H, editors. Bioactive Volatile Compounds from Plants. ACS Symposium Series 525. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1993. pp. 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hahlbrock K, Scheel D, Logemann E, Nürnberger T, Parniske M, Reinold S, Sachs WR, Schmelzer E. Oligopeptide elicitor-mediated defense gene activation in cultured parsley cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4150–4157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Croteau R. Biochemistry of conifer resistance to bark beetles and their fungal symbionts. In: Fuller G, Nes WD, editors. Ecology and Metabolism of Plant Lipids. ACS Symposium Series 325. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1987. pp. 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh S, Croteau R. Individual variation in constitutive and induced monoterpene biosynthesis in grand fir (Abies grandis) Phytochemistry. 1997;47:577–582. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Rohl AE (1989) Pine oil and miscellaneous uses. In DF Zinkel, J Russell, eds, Naval Stores: Production, Chemistry, Utilization. Pulp Chemicals Association, New York, pp 560–572

- LaFever RE, Stofer Vogel B, Croteau R. Diterpenoid resin acid biosynthesis in conifers: enzymatic cyclization of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate to abietadiene, the precursor of abietic acid. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;313:139–149. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn E, Gijzen M, Croteau R. Defense mechanisms of conifers. Differences in constitutive and wound-induced monoterpene biosynthesis among species. Plant Physiol. 1991a;96:44–49. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn E, Gijzen M, Croteau R. Regulation of monoterpene biosynthesis in conifer defense. In: Nes WD, Parish EJ, Trzaskos JM, editors. Regulation of Isopentenoid Metabolism. ACS Symposium Series 497. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1992. pp. 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn E, Gijzen M, Muzika RM, Barton K, Croteau R. Oleoresinosis in grand fir (Abies grandis) saplings and mature trees. Modulation of this wound response by light and water stresses. Plant Physiol. 1993a;101:1021–1028. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.3.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn E, Gijzen M, Savage TJ, Croteau R. Defense mechanisms of conifers. Relationship of monoterpene cyclase activity to anatomical specialization and oleoresin monoterpene content. Plant Physiol. 1991b;96:38–43. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn E, Savage TJ, Gijzen M, Croteau R. Simultaneous analysis of monoterpenes and diterpenoids of conifer oleoresin. Phytochem Anal. 1993b;4:220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn E, Steele CL, Croteau R. Simple isolation of functional RNA from woody stems of gymnosperms. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1994;12:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mau CJD, West CA. Cloning of casbene synthase cDNA: evidence for conserved structural features among terpenoid cyclases in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8497–8501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey D, Croteau R. Terpenoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1015–1026. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moesta P, West CA. Casbene synthetase: regulation of phytoalexin biosynthesis in Ricinus communis L. seedlings. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;238:325–333. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebeker TE, Hodges JD, Blance CA. Host response to bark beetle and pathogen colonization. In: Schowalter TD, Filip GM, editors. Beetle-Pathogen Interactions in Conifer Forests. London: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 158–173. [Google Scholar]

- Norin T. Some aspects of the chemistry of the order pinales. Phytochemistry. 1972;11:1231–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Raffa KF (1991) Induced defenses in conifer-bark beetle systems. In DW Tallamy, MJ Raupp, eds, Phytochemical Induction by Herbivores. Academic Press, New York, pp 245–276

- Raffa KF, Berryman AA, Simasko J, Teal W, Wong BL. Effects of grand fir monoterpenes on the fir engraver, Scolytus ventralis (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), and its symbiotic fungus. Environ Entomol. 1985;14:552–556. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp 10.16–10.17

- Satterwhite DM, Croteau R. Applications of gas chromatography to the study of terpenoid metabolism. J Chromatogr. 1988;452:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)81437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CL, Crock J, Bohlmann J, Croteau R. Sesquiterpene synthases from grand fir (Abies grandis): comparison of constitutive and wound-induced activities, and cDNA isolation, characterization, and bacterial expression of δ-selinene synthase and γ-humulene synthase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2078–2089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CL, Lewinsohn E, Croteau R. Induced oleoresin biosynthesis in grand fir as a defense against bark beetles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4164–4168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoessl A, Stothers JB, Ward EB. Sesquiterpenoid stress compounds of the Solanaceae. Phytochemistry. 1976;15:855–872. [Google Scholar]

- Stofer Vogel B, Wildung M, Vogel G, Croteau R. Abietadiene synthase from grand fir (Abies grandis): cDNA isolation, characterization and bacterial expression of a bifunctional diterpene cyclase involved in resin acid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23262–23268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfall DR, Whitehead IM. Co-ordinated inhibition of squalene synthetase and induction of enzymes of sesquiterpenoid phytoalexin biosynthesis in cultures of Nicotiana tabacum. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:2567–2580. [Google Scholar]

- Threlfall DR, Whitehead IM. Terpenoid phytoalexins: aspects of biosynthesis, catabolism and regulation. In: Harborne JB, Tomas-Barberan FA, editors. Ecological Chemistry and Biochemistry of Plant Terpenoids. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1991. pp. 159–208. [Google Scholar]

- Vögeli U, Chappell J. Induction of sesquiterpene cyclase and suppression of squalene synthetase activities in plant cell cultures treated with fungal elicitor. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:1291–1296. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.4.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West CA, Lois AF, Wickham KA, Ren Y (1989) Diterpenoid phytoalexins: biosynthesis and regulation. In GHN Towers, HA Stafford, eds, Biochemistry of the Mevalonic Acid Pathway to Terpenoids. Plenum Press, New York, pp 219–248

- Yamada T. Biochemistry of gymnosperm xylem responses to fungal invasion. In: Blanchette RA, Biggs AR, editors. Defense Mechanisms of Woody Plants against Fungi. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 147–184. [Google Scholar]

- Zook MN, Chappell J, Kuc JA. Characterisation of elicitor-induction of sesquiterpene cyclase activity in potato tuber tissue. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:3441–3445. [Google Scholar]