Abstract

Background:

Burden of treatment refers to the workload of health care as well as its impact on patient functioning and well-being. We set out to build a conceptual framework of issues descriptive of burden of treatment from the perspective of the complex patient, as a first step in the development of a new patient-reported measure.

Methods:

We conducted semistructured interviews with patients seeking medication therapy management services at a large, academic medical center. All patients had a complex regimen of self-care (including polypharmacy), and were coping with one or more chronic health conditions. We used framework analysis to identify and code themes and subthemes. A conceptual framework of burden of treatment was outlined from emergent themes and subthemes.

Results:

Thirty-two patients (20 female, 12 male, age 26–85 years) were interviewed. Three broad themes of burden of treatment emerged including: the work patients must do to care for their health; problem-focused strategies and tools to facilitate the work of self-care; and factors that exacerbate the burden felt. The latter theme encompasses six subthemes including challenges with taking medication, emotional problems with others, role and activity limitations, financial challenges, confusion about medical information, and health care delivery obstacles.

Conclusion:

We identified several key domains and issues of burden of treatment amenable to future measurement and organized them into a conceptual framework. Further development work on this conceptual framework will inform the derivation of a patient-reported measure of burden of treatment.

Keywords: conceptual framework, patient-centered, medication therapy management, adherence, questionnaire, minimally disruptive medicine

Introduction

Patients with chronic health conditions experience burden not only from their illness, but also from their ever-expanding health care regimens that can include medication-taking, keeping medical appointments, monitoring health, diet, and exercise.1,2 Excessive health care burden can trigger a spiral of negative consequences. Burdened patients may struggle with adhering to prescribed treatments and care.3–7 Nonadherence to necessary care can lead to more hospitalizations and higher mortality.8,9 The physician’s response to poor patient outcome is often to intensify treatment,1 and this can result in an increased regimen burden, as already burdened patients are asked by their physicians to do more. This treatment burden can also lead to poor quality of life, as patients spend more of their time, energy, and resources on staying well.10–12

Part of the solution to the problem of treatment burden may lie in what May et al have termed “minimally disruptive medicine”.1 Minimally disruptive medicine refers to forms of effective treatment and service provision designed to advance patient’s health care goals with the least health care burden. A critical step to achieving this is establishing the weight of treatment burden on the patient. To do this, sound and reliable measurement must be available.

We define “burden of treatment” as the workload of health care and its impact on patient functioning and well-being. “Workload” includes the demands made on a patient’s time and energy due to treatment for a condition(s) as well as other aspects of self-care (eg, health monitoring, diet, exercise).1,2,13 “Impact” includes the effect of the workload on the patient’s behavioral, cognitive, physical, and psychosocial well-being.11,14–17 Some studies have developed measures of burden of treatment for specific health conditions like diabetes,10,11 heart failure,15 cancer,14 and end-stage renal disease.18 While useful in the single-disease context, these measures are less appropriate for patients with multiple comorbidities because they specify issues reflecting experience with a particular disease (eg, the inconvenience of insulin for diabetes, the side effects of chemotherapy for cancer, the psychosocial consequences of kidney dialysis for renal disease). A more comprehensive understanding of burden of treatment, one not restricted to the problems manifest in any single disease, is needed if we are to comprehend fully how burden of treatment is experienced by the patient with multiple and complex health conditions.1 Meeting this need today is paramount as the proportion of people suffering from multiple and complex health conditions continues to grow.19

We plan to build a general, multi-domain, patient-reported measure of burden of treatment with wide applicability across diseases and treatments. Developing a self-report measure is an iterative process that involves qualitative and quantitative methods.20–22 Articulation of a conceptual measurement framework using qualitative methods and direct patient input is an important first step.20 A conceptual framework can justify development of a new or modified measure and serve as a “content road map” identifying the issues to address in the final measure. Currently, there is no conceptual framework for burden of treatment applicable to patients with multiple and complex chronic health conditions.

In this study, we conducted semistructured qualitative interviews with patients to achieve the following objectives: identify issues (ie, themes and subthemes) illustrative of burden of treatment from the perspective of the complex patient and inform derivation of a general, patient-reported measure of burden of treatment flexible enough for application across any disease or treatment regimen.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants in this study were medical outpatients newly enrolled in a pharmacist-led medication therapy management program at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. In medication therapy management, patients collaborate with a pharmacist who advises them on optimal ways to manage a drug regimen to maximize therapeutic outcome. These patients were well suited for studying burden of treatment because all were involved in a complex regimen of self-care including taking multiple medications, monitoring health, diet, and exercise, and were coping with one or more chronic conditions. Patients had to be at least 18 years old and able to travel to the clinic for the study.

Procedure

The medication therapy management program coordinator identified eligible patients who were then mailed an introductory letter and contacted by phone to gauge interest in participating. Interested patients were scheduled for an interview that was conducted in a private clinic room. Interviewers received formal training from a qualitative methodologist experienced in semistructured interviewing procedures. Most interviews were completed in under 90 minutes (mean 51 minutes). Patients received $30 compensation. The Mayo Clinic institutional review board approved the study and all participants provided their written informed consent and authorized the use and disclosure of their health information (IRB 09-006014 00). The interviews were conducted between January 2010 and October 2011.

Interview protocol

The interview featured a series of open-ended questions (see Supplementary data file 1 for the interview schedule). Prior studies of treatment impact and satisfaction10,11,23 and May et al’s normalization process theory2,24 informed the questions. Normalization process theory has been used to understand the “work” involved in sickness careers.25 It explains how the work of enacting a collection of practices is accomplished through the operation of four basic mechanisms, ie, coherence (sense-making work), cognitive participation (relationship work), collective action (enacting work), and reflexive monitoring (appraisal work). A qualitative methodologist inspected and refined the questions, then organized them into a logical flow from broad to specific. A few questions were modified (eg, wording simplified) or added during the course of the study to clarify important content arising in earlier interviews. For instance, we added questions tapping the impact of treatment and self-care on the patient’s life, social relationships, and finances, as well as a question on personal means of coping with self-management since these issues spontaneously emerged in the early interviews. Other questions queried patients about their health conditions, required treatments and self-care, relationships with health care providers, and support from others. Participants provided basic descriptive information (eg, age, education, race/ethnicity, and marital and occupational status) at the end of the interview. Interviews were recorded and professionally transcribed for later thematic analysis.

Analysis

Ritchie and Lewis’ framework analysis was used to synthesize themes from the interview transcripts.26 The first and second author independently reviewed transcripts from the first five interviews to identify key themes and subthemes (ie, patterns within the narrative data), then developed a coding scheme through discussion and consensus. The scheme provided a “framework” which was systematically applied to code themes in later interview transcripts. Narrative text illustrating a coded theme or subtheme was indexed. We reviewed the framework after an additional 10 interviews, updating it to reflect newly revealed themes and subthemes (ie, meaningful content not apparent in earlier interviews). Hence, data collection and data analysis were concurrent. The process continued until thematic content saturation was reached (ie, the point at which no new themes emerged from the narrative data).20 Saturation was reached after 25 interviews; however, seven more interviews were conducted because they had already been scheduled. Using the themes and subthemes emerging from the narrative data, we outlined a conceptual framework of burden of treatment. This strategy is consistent with best practices for establishing content validity of patient-reported measures.20,27

Results

We contacted 52 patients, 32 of whom agreed to be interviewed (ie, a 62% response rate). Of the 20 patients who declined, most (60%) cited lack of time or interest. Participant demographic and medical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most patients were female (63%), white (97%), educated (84% at least some college), and married or living with a partner (69%). Almost half were full-time or part-time employed (44%). Patients self-reported experiencing 1–16 health conditions (median 5). Overall, a total of 50 different health conditions were reported, with the most frequently reported conditions being gastrointestinal problems, hypertension, arthritis/joint pain, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, hyperlipidemia, back/neck problems, eye problems, and sleeping problems.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and medical characteristics (n = 32)

| Age | Median 59.5 years |

| Range 26–85 years | |

| Gender | Female, 20 (63%) |

| Male, 12 (38%) | |

| Race | White, 31 (97%) |

| African-American, 1 (1%) | |

| Education | Some college/technical degree, 11 (34%) |

| College graduate, 9 (28%) | |

| Advanced college degree, 7 (22%) | |

| High school graduate or less, 5 (16%) | |

| Marital status | Married or living with partner, 22 (69%) |

| Not married, 10 (31%) | |

| Employment status | Retired/unemployed, 13 (41%) |

| Full-time employed, 10 (31%) | |

| Part-time employed, 4 (13%) | |

| On disability or leave, 4 (13%) | |

| Homemaker, 1 (3%) | |

| Number of self-reported health conditions | Median 5 |

| Range 1–16 | |

| Types of health conditions (top 10 most reported) | Gastrointestinal problems: 15 (eg, reflux, irritable bowel, constipation) |

| Hypertension, 14 | |

| Arthritis/joint pain, 13 | |

| Diabetes, 12 | |

| Cardiovascular disease, 10 | |

| Depression, 10 | |

| Hyperlipidemia, 8 | |

| Back/neck problems, 8 | |

| Eye problems, 8 (eg, glaucoma, cataracts) | |

| Sleeping problems, 7 (eg, insomnia, apnea) |

Burden of treatment: major themes and subthemes

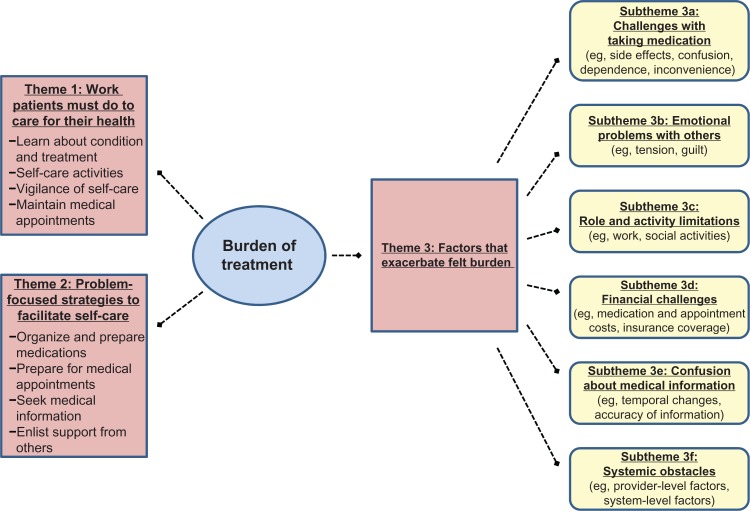

We identified the following three broad themes of burden of treatment: the work patients must do to care for their health, problem-focused strategies and tools to facilitate the work of self-care, and factors that exacerbate perceived treatment burden. The third theme encompasses several subthemes. Each of these themes and subthemes are explained below and illustrated using quoted passages from the interviews (with additional quotes appearing in Supplementary data file 2). A measurement framework incorporating these themes and subthemes appears in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Measurement framework of burden of treatment.

Theme 1: work patients must do to care for their health

All patients (100%) described doing a number of things to manage their conditions optimally and stay as well as possible. For instance, the following diabetic patient described having to learn about his condition and its treatment, including learning and developing the skills to manage it:

The diabetes with the needles and injecting myself was a pretty big step because I was scared to death of needles… now it doesn’t bother me… but you know you have to do it so you know [how] to do it. And I guess, the main thing with that is that I had to find a place where I wouldn’t bruise, because I bruise easily… that was something to figure out

(52-year-old white male).

Several patients described how self-care is ever present in their lives, involving constant vigilance in both action and thought. For instance, this woman described her ongoing struggle to cope with anxiety, depression, and seasonal affective disorder.

Dealing with these things is an everyday battle… it is something I think about every day and how I’m going to cope and if I run into situations how am I going to deal with it?

(46-year-old white female).

A 36-year-old man described how ruminating about his chronic back pain affects him.

It affects me because I’m constantly thinking I have to do something… If I’m sitting on the couch – oh, I should probably be up stretching my back or I should probably be icing or I should probably be walking around

(36-year-old white male).

The most frequently mentioned self-care activities included taking medications as recommended, monitoring health, dieting, and exercising. Many participants spoke of the need to take medications every day, as illustrated in the following quotes by a man with atrial fibrillation and a woman with reactive airway disease:

I’m on pills three times a day to reduce the incidence of atrial fibrillation

(63-year-old white male).

Five inhalers every day! It is either nasal or through the mouth – 5 of them!

(61-year-old white female).

Many diabetic patients are required to track their blood sugar levels and insulin injections as indicated by this woman with type 1 diabetes.

I have to keep daily records of blood sugars and the amount of insulin that I take and if the day was a usual day… And he [the physician] looks at those records

(67-year-old white female).

This same woman was suffering from celiac disease and explained the difficulty of following a gluten-free diet.

It is the most awful thing I have to do every day. It limits choices to the extent that, it really controls where you go and when you look at a menu what you order. I get tired of ordering salads and bringing my gluten-free carbohydrate…

(67-year-old white female).

Finally, patients also described maintaining regular medical appointments and consulting with a variety of health care providers. This 63-year-old obese man with cardiovascular disease and cataracts appears frustrated by the need to see so many different doctors so often.

I have seen more cardiac people in the last 3 years than I ever knew existed… the eye doctor is whoever happens to pull my name when the appointment comes. I am seeing a… I call her the ‘fat’ doctor about twice a year, maybe 3 times a year

(63-year-old white male).

Theme 2: problem-focused strategies and tools to facilitate the work of self-care

Most patients (84%) described using a variety of strategies and tools to facilitate the work of taking care of themselves. While some of these activities may be voluntary, they do require time and energy and arise out of the need to care for a health condition(s). They can add to a patient’s self-care workload and, therefore, the overall sense of treatment burden. Organizing and preparing medicines was frequently mentioned, with several patients reporting use of a pill organizer to help manage the taking of multiple medications, as illustrated by the following quote:

We have pill boxes. We have them Sunday through Saturday pill boxes… I take several different things in the morning and then I take a few things at night and I have two for, you know, I have got them separated and marked for am and pm

(74-year-old white female).

In addition to the work of showing up to scheduled medical appointments (theme 1), some patients also reported doing homework to prepare for appointments. This appears to be particularly helpful prior to appointments with a primary care physician, as illustrated by these remarks from two women coping with a large number of health conditions (9 and 16, respectively).

I have a history that has worked out and I keep that pretty current and so I just go over it carefully… I do my homework a little bit, because otherwise you are going in cold and you don’t get the things accomplished

(85-year-old white female).

I always have a list of something and we talk about any questions or concerns, so I know the date when I started meds or if I had any other things… So I always try to go in organized. Be as organized as I can be, ahead of time to make it easier for him [the doctor] and easier for me

(66-year-old white female).

Many patients also reported seeking information about their health condition(s), including keeping abreast of current research. Popular sources of this information included books, scientific journals, or the Internet. For instance, new diagnoses prompted this woman to seek out information about her conditions from various professional organizations.

Once I found out about it [diagnosis of endometriosis], I started reading up about it, and for years I belonged to the endometriosis association and read quite a few books on it… then the arthritis, I joined the arthritis foundation so I read their stuff

(52-year-old white female).

Finally, patients also reported enlisting support from others to help care for their conditions. This is illustrated in the following quote from a woman with diabetic retinopathy.

I was supposed to look at my feet once a week, but I can’t see my feet because of my poor vision. So, I have a friend come in once a week and she looks, and makes sure there aren’t any cuts or any issues

(54-year-old white female).

Theme 3: factors that exacerbate perceived treatment burden

We identified six global factors that could enhance and promote a feeling of burden with the health care regimen. These include challenges with taking medication, emotional problems with family/friends, role and social activity limitations, financial challenges of health care, confusion about medical information, and systemic obstacles of health care delivery. Each of these is described and illustrated below.

Subtheme 3a: challenges with taking medication

Many patients (75%) identified frustrating consequences of taking medication. Among these were medication side effects, including drug-to-drug interactions, as indicated in the following quotes.

I would like to get rid of the Abilify. It caused me a lot of weight gain, I gained over 30 lbs and I have never had a problem with weight before that

(46-year-old white female).

I just struggle with not feeling really good a lot of the time because of all the meds I’m on and ya know the interaction with one another…

(60-year-old white female).

Some patients also reported being confused about medications (eg, what to take, when to take it, the purpose of the medication). The sheer number of medications that the following patient needed for his cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes led to confusion about when they needed to be taken.

…some of them I was takin’ before meals, and you got to take them after. It just says, ‘take one a day or take one in the morning and one in the evening.’ It didn’t say after or before, so I didn’t know

(64-year-old white male).

Other patients expressed concern about a growing dependence on medication, as illustrated by this woman taking medication for hypothyroidism, depression, and migraine headaches.

It is like, wow, I am so in need of this stuff! Which is scary because what if something happened and you don’t have your meds and… you know? I don’t like being that dependent on them, but then again, what do you do?

(54-year-old white female).

Finally, some patients described a sense of frustration at the inconvenience of medications, especially with how they interfere with daily life or other important routines like travelling.

…that interferes most with my lifestyle. Because of the medication I take, I start taking at 6:00 pm and by 7 pm I’m wasted, just exhausted. I mean it is so many

(58-year-old white female).

Travel is a big issue… making sure I have everything when I go and forgetting something when I get somewhere. It is not real easy to get a prescription transferred

(41-year-old white male).

Subtheme 3b: emotional problems with family/friends

A few patients (28%) remarked that the work of caring for themselves could produce tension or evoke feelings of guilt with close family members, friends, or coworkers. A 52-year-old man whose health forced him to cut back to part-time employment spoke of tension with his spouse.

…I mean a lot of that has been completely on my wife as far as paying the house note and most of the bills through a lot of this, and that’s caused tension, of course… We have been on this kind of rocky road

(52-year-old white male).

A 54-year-old diabetic woman recounted how her self-care demands were negatively affecting her relationship with her mother.

…I think she [patient’s mother] doesn’t want it to be like that. ‘This isn’t fair! Why do their daughters get to come out to see them and why can’t my daughter do what their daughters can do?’ ‘Well, you know mom, I have diabetes and it is bad and this is the way it is’

(54-year-old white female).

Subtheme 3c: role and activity limitations

The health care regimen could also interfere with the performance of important roles, such as paid work, and limit one’s engagement in social activities. Forty-four percent of patients described some role or social activity limitation. For example, some patients described how difficult it can be to schedule medical appointments around work time.

I have appointments that I have to go to, and to get them scheduled on my day off. I do work, 0.8, so I usually have one day off during the week. But, of course, the doctors aren’t always there on the days that you have off

(46-year-old white female).

PTO [paid time off], yah, I got to end up taking time off… yesterday was the first day all week I have been able to go to work

(36-year-old white male).

Caring for a health condition during work can interfere with work capacity, as indicated by this woman coping with recurrent kidney stones:

At work, the main thing would be the straining of the urine [to catch the stone]. And you’re uncomfortable, sometimes you’re in pain while you’re working… it slows you down, I think. You’re not working at your full capacity

(60-year-old white female).

Social limitations voiced by patients reflected concerns with not being able to spend time with family and friends and not having the time to pursue more personally rewarding activities.

…like after work, if I go out with friends, like I might stay out and be like, I have to go home because I need to take my medication

(26-year-old white male).

And, you know, it gets to be a little bit too much. I just think it is… that is all I can say is that the doctors don’t add any more. Just don’t add any more self-care… there are so many other things I’d like to be doing… And eventually, I want to volunteer… I want to do that so bad, but I have either not felt up to it or I haven’t had the time to work it in

(69-year-old white female).

Subtheme 3d: financial challenges of health care

A significant contributor to perceived treatment burden appears to be the financial impact of health care, voiced by 59% of the patients interviewed. Specifically, many patients expressed concern over the high out-of-pocket costs for medications and medical appointments.

The medications are just astronomical when it comes to money, to paying for them. I pay over, I think, $300 a month just on medications

(46-year-old white female).

Am I going to be able to afford my meds? Will I have to work forever? Can I work forever? You know, when you have all these kinds of things, these spendy meds, how’s that gonna play out for me? And that’s a huge worry

(60-year-old white female).

Another frequently mentioned issue was concern about reimbursement, especially for medications. A 60-year-old woman shared her story of an unsuccessful attempt to maintain reimbursement for the only cholesterol lowering medication she could comfortably tolerate.

I got notification from the [insurance company] that they will not pay for Lipitor. So I called the Lipitor people and said I need help, and they said ‘No, you make too much money to get that help. I said you know I’m not gonna go through that whole process of trying all of these meds again when this works wonderful…’ So I’m just self-paying for my Lipitor

(60-year-old white female).

Patients also exhibited apprehension about insurance coverage, as this comment from an 85-year-old retired woman illustrates:

I am under Medicare, but my insurance was Blue Cross/Blue Shield. So I continually have to be on top of that. Sometimes one of them doesn’t pay and then I have to… just that sort of thing, just typical insurance

(85-year-old white female).

Subtheme 3e: confusion about medical information

A few patients (19%) expressed confusion over receiving conflicting and sometimes contradictory medical information. Frustration was apparent in response to temporal changes in medical advice, especially among patients with diabetes.

One diet says I can eat so much of this, one diet says I can’t… all those years of diabetes, they said you can’t eat certain things, and now they say you can’t eat certain things

(54-year-old white male).

The recent thing in diabetes is the drive to understand carbohydrates. It used to be you were told rule out sugar… and they didn’t concentrate on carbohydrates. Now they are. And, so that is a little frustrating

(75-year-old white female).

Subtheme 3f: systemic obstacles of health care delivery

Certain features of health care delivery can negatively influence well-being and lower perceptions of care. These include individual, provider-level, and system-wide factors (reported by 44% of patients). Provider-level factors manifest as a lack of trust or poor communication with one’s health care provider. The quotes below describe the provider-patient relationship, highlighting potential conflicts of interest between provider goals (eg, revenue maximization) and patient goals (eg, wellness).

I was told by one of the doctors that I wasn’t coming often enough because my frequency of visiting him didn’t meet his requirements for getting increased reimbursement from the health plans… so I fired him because he made it about him and not about me

(41-year-old white male).

I don’t like coldness. I want them [the doctors] to listen. And I try for that. I try not to say too much to irritate them because they are busy. But I try to get some kind of a rapport, and if I don’t get it, it is very uncomfortable

(85-year-old white female).

Troublesome organizational or system-wide factors mentioned included lack of care coordination and continuity, as illustrated, respectively, in the following patient quotes:

The patient is in the middle, and the patient is talking to this doctor, and the patient is talking to that doctor and this doctor says this, and this doctor says this, and I don’t have the medical knowledge and I’m like, could you just sit down together and work this out and then tell me what to do?

(52-year-old white female).

I don’t want to have to start from scratch with somebody and explain the whole story or whatever… Yah, my doctor I couldn’t get in on Tuesday so I just took whoever they had and I had never met her before in my life and she doesn’t know what is going on

(36-year-old white male).

Discussion

We developed a conceptual framework of issues defining the burden of treatment in patients with multiple chronic health conditions and complex regimens of self-care using qualitative interviews. A conceptual measurement framework serves as the foundation upon which a patient-reported measure is built. It stipulates the issues and domains that will be represented as items and subscales in the final measure, ensuring its content validity.20,28 This study is a first step in developing a patient-centered, subjective measure of burden of treatment, an important goal of our work.

Developing and validating a sensitive general measure of burden of treatment has potential clinical value. Physicians and other health care providers could use patient feedback about burden to help plan less disruptive treatment regimens. Burden of treatment data could trigger clinical action to alter a treatment regimen that may be exceeding a patient’s capacity. As a recently derived model of patient complexity stipulates, imbalance between workload (ie, the demands of care) and an individual’s capacity (ie, available resources to handle the workload) can lead to disruptions in care and consequently poor clinical outcome.13 Treatment burden information could also facilitate conversations between patients and their providers about the challenges inherent in maintaining a given treatment regimen. It could even signal when an intervention like medication therapy management might be needed. Ultimately, the goal of all of these actions is to promote minimally disruptive medicine. Data from a general measure of burden of treatment could also inform health care and health policy by virtue of its use in randomized trials and analyses of comparative effectiveness.

While we did not set out to test any particular theory of health or behavior formally, some of our interview questions were informed by May’s normalization process theory. This theory has recently been used to describe the treatment and self-care burden of primary care patients living with heart failure in the UK.2 Elements of all four of the basic mechanisms of normalization process theory are apparent in the themes and subthemes of our measurement framework. Sense-making work is characterized in our theme 1 (work patients must do to care for their health) as patients engage in learning about their health condition and the treatment for it. Aspects of relationship work are revealed in our theme 2 (problem-focused strategies to facilitate self-care) in the form of patients enlisting support from others, such as family members and friends. Enacting work or the day-to-day activities and challenges of self-care such as attending medical appointments, taking medications, paying for health care, and interacting with providers and the health care system were apparent in several of our themes and subthemes, including theme 1 (work patients must do), theme 2 (problem-focused strategies), subtheme 3a (challenges with taking medication), subtheme 3d (financial challenges), and subtheme 3f (health care delivery obstacles). Finally, appraisal work or monitoring and tracking treatment effects is embedded in the necessary self-care activities described in our theme 1. Hence, the measurement framework specified in this study appears to converge with the broader theory of normalization process theory. Together, both can help us understand the concept of burden of treatment.

Our study is not without limitations. First, we consider the current version of our measurement framework to be somewhat preliminary because it was based on input from patients affiliated with a single center and a single therapeutic program. Furthermore, lack of socioeconomic and racial/ethnic diversity in the sample may limit representativeness of some findings. We will seek greater representation from economically disadvantaged groups and racial/ethnic minorities as our work continues. Second, we relied on a single method of data collection, the one-on-one interview. Use of a different qualitative method, such as focus groups, could have produced different results. Third, information on patient medical and health conditions was provided by self-report. Medical record review might yield data that are more objectively accurate and reliable. Fourth, certain issues represented in the framework may be unique to the American health care system given that the study sample was made up of US patients. In their study of heart failure patients in the UK, Gallacher et al2 pointed out that differences in health care systems may produce differences in treatment burden. For example, financial constraints and negotiations with insurers may be more of a consideration to US patients than patients in the UK or other countries with socialized health care systems. Finally, several patients declined to participate due to lack of time. Some of these patients may have had high levels of burden.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the limitations mentioned, we have developed a suitable version of a patient-informed conceptual framework of burden of treatment in primary care (see Figure 1). Our future work will build from this foundation and involve further qualitative study with other well defined groups of patients experiencing burden of treatment, including more diverse populations and patients served in other health care settings. This will help to clarify, augment, and confirm the framework, and ultimately guide item writing and drafting of a pilot instrument amenable to testing in large-scale, survey studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Sponsorship Research Board of St Marys Hospital (Rochester, MN) and the Mayo Clinic’s Center for Translational Science Activities through grant number UL1 RR024150 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health. DE, DO, CM, and VM are part of the International Minimally Disruptive Medicine Workgroup. Workgroup members include Victor Montori, Carl May, Nilay Shah, Frances Mair, Sara Macdonald, Nathan Shippee, Katie Gallacher, David Eton, Djenane Oliveira, Kathleen Yost, Robert Stroebel, AnneRose Kaiya, Leona Han, and Amy Bodde.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Supplementary data file 1

Interview schedule

Question 1 Tell me how you’re doing these days. What types of health problems are you dealing with right now?

Question 2 What kinds of things do you have to do to treat or care for your health condition?

Do you monitor your condition(s) on your own (eg, check your blood pressure)? What type of monitoring do you do and how often?

Have you had to learn anything new (eg, new skills) in order to care for yourself?

Question 3 Thinking of all of these things that you have to do to care for your health, how would you say they affect you or your life?

Question 4 Do your treatments or self-care affect your work, or your social and family life? How so? How big a part of your life would you say is made up of activities you do to manage your health and illnesses?

Question 5 Are there times when you find that it is difficult to do all of the things that you have to do to maintain your health? Do you ever cut back on doing things for your health?

Question 6 Tell me a little bit about the relationships that you have with your health care providers? Is communication between you and the providers particularly good or bad? Can you give an example to illustrate this?

Question 7 In caring for your health, do you get support from other people? Who? What kinds of things do they do to help you? Has your health care ever created tension between you and other people?

Question 8 For some people, the personal work of caring for their health condition can be emotionally challenging? Is this true for you? Are there any things that you do to “stay positive” or “keep your spirits up”?

Question 9 Has your health care affected you at all financially?

Question 10 Are there things that you routinely do to make management of your health condition easier?

Question 11 Is there anything else that you would like to tell me about today regarding your health conditions and how they are cared for?

Supplementary data file 2

Additional patient quotes

Theme 1: the work patients must do to care for their health

“I would say it is a full time job [managing diabetes]… So I would consider myself working at least two full time jobs” (41-year-old white male).

“And the days just seem to revolve around, making sure I get the insulin, making sure I get the meals on time… making sure that I am doing all the right things” (67-year-old white female).

Theme 2: problem-focused strategies and tools to facilitate the work of self-care

[Preparing medicines] “At home I have a pill cutter. I should start cutting up a whole week’s worth, but it is just a pain, I don’t do it other than when I have to… It is just time consuming to do” (36-year-old white male).

[Researching condition] “I keep up on all of the clinical studies and all the research that is going on, so I’m pretty up-to-date on that” (41-year-old white male).

“I do a lot of research on the Internet. And I have for this condition [atrial fibrillation], as well” (63-year-old white male).

Theme 3a: challenges with taking medication

[Side effects] “I’m not sleeping as well as I would like because of intolerance to pain medication (for fibromyalgia symptoms)” (61-year-old white female).

“Side effects, side effects, let’s hear side effects!.. the Elavil, I have a dry mouth, constipation, some dizziness… I don’t like being on this higher dose of Atenolol; I feel a little bit like I’m walking in a fog” (52-year-old white female).

[Interference with daily life] “Having to set my alarm is just an annoying daily thing when I don’t even have to get up; I have to set it because I have to take a pill” (26-year-old white male).

Theme 3c: role and activity limitations

[Social activity limitations] “And people wanted me to come and play bridge and to do other things, and I think, on the higher dose of the prednisone I feel tremulous and it is more difficult to concentrate” (66-year-old white female).

Theme 3d: financial challenges of health care

[Reimbursement] “Oh, it is a burden. Last year we used to be able to, anything that was a prescription, or even not a prescription, as long as your doctor said you need to take this; I could get reimbursed from my health care spending account. Now can’t do that anymore, prescription stuff only” (36-year-old white male).

Theme 3f: systemic obstacles of health care delivery

[Negative provider-patient relationship] “My neurologist, at times, asks a question and won’t listen to the answer and asks it again and won’t listen to the answer… so I have told him several times – you need to slow down and listen to me. And I mean that is pretty bold but, I mean he pisses me off ” (58-year-old white female).

References

- 1.May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. Br Med J. 2009;339:b2803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallacher K, May CR, Montori VM, Mair FS. Understanding patients’ experiences of treatment burden in chronic heart failure using normalization process theory. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:235–243. doi: 10.1370/afm.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durso SC. Using clinical guidelines designed for older adults with diabetes mellitus and complex health status. JAMA. 2006;295:1935–1940. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.16.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graves MM, Adams CD, Bender JA, Simon S, Portnoy AJ. Volitional nonadherence in pediatric asthma: parental report of motivating factors. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7:427–432. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes RB, McDonald HP, Garg AX. Helping patients follow prescribed treatment: clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;288:2880–2883. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunt T, Snoek FJ. Barriers to insulin initiation and intensification and how to overcome them. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2009;164:6–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vijan S, Hayward RA, Ronis DL, Hofer TP. Brief report: the burden of diabetes therapy: implications for the design of effective patient-centered treatment regimens. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:479–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1836–1841. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297:177–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson RT, Skovlund SE, Marrero D, et al. Development and validation of the insulin treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Clin Ther. 2004;26:565–578. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brod M, Hammer M, Christensen T, Lessard S, Bushnell DM. Understanding and assessing the impact of treatment in diabetes: the Treatment-Related Impact Measures for Diabetes and Devices (TRIM-Diabetes and TRIM-Diabetes Device) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:83. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pifferi M, Bush A, Di Cicco M, et al. Health-related quality of life and unmet needs in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:787–794. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00051509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, Mair FS, Montori VM. Workload, capacity, and burden: a functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.05.005. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henry DH, Viswanathan HN, Elkin EP, Traina S, Wade S, Cella D. Symptoms and treatment burden associated with cancer treatment: results from a cross-sectional national survey in the US. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett SJ, Milgrom LB, Champion V, Huster GA. Beliefs about medication and dietary compliance in people with heart failure: an instrument development study. Heart Lung. 1997;26:273–279. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(97)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griva K, Jayasena D, Davenport A, Harrison M, Newman SP. Illness and treatment cognitions and health related quality of life in end stage renal disease. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14:17–34. doi: 10.1348/135910708X292355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snoek FJ, Pouwer F, Welch GW, Polonsky WH. Diabetes-related emotional distress in Dutch and US diabetic patients: cross-cultural validity of the problem areas in diabetes scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1305–1309. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy SP, Powers MJ, Jalowiec A. Psychometric evaluation of the Hemodialysis Stressor Scale. Nurs Res. 1985;34:368–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu S, Green A. Projection of Chronic Illness Prevalence and Cost Inflation. Washington, DC: Rand Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1263–1278. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost MH, Reeve BB, Liepa AM, Stauffer JW, Hays RD. What is sufficient evidence for the reliability and validity of patient-reported outcome measures? Value Health. 2007;10(Suppl 2):S94–S105. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner RR, Quittner AL, Parasuraman BM, Kallich JD, Cleeland CS. Patient-reported outcomes: instrument development and selection issues. Value Health. 2007;10( Suppl 2):S86–S93. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, et al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.May CR, Mair F, Finch T, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: normalization process theory. Implement Sci. 2009;4:29. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.May C. Retheorizing the clinical encounter. In: Scambler G, Scambler S, editors. Assaults on the Lifeworld: Directions in the Sociology of Chronic and Disabling Conditions. London, UK: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London, UK: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McColl E. Developing questionnaires. In: Fayers P, Hays RD, editors. Assessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials: Methods and Practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothman ML, Beltran P, Cappelleri JC, Lipscomb J, Teschendorf B. Patient-reported outcomes: conceptual issues. Value Health. 2007;10( Suppl 2):S66–S75. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Interview schedule

Question 1 Tell me how you’re doing these days. What types of health problems are you dealing with right now?

Question 2 What kinds of things do you have to do to treat or care for your health condition?

Do you monitor your condition(s) on your own (eg, check your blood pressure)? What type of monitoring do you do and how often?

Have you had to learn anything new (eg, new skills) in order to care for yourself?

Question 3 Thinking of all of these things that you have to do to care for your health, how would you say they affect you or your life?

Question 4 Do your treatments or self-care affect your work, or your social and family life? How so? How big a part of your life would you say is made up of activities you do to manage your health and illnesses?

Question 5 Are there times when you find that it is difficult to do all of the things that you have to do to maintain your health? Do you ever cut back on doing things for your health?

Question 6 Tell me a little bit about the relationships that you have with your health care providers? Is communication between you and the providers particularly good or bad? Can you give an example to illustrate this?

Question 7 In caring for your health, do you get support from other people? Who? What kinds of things do they do to help you? Has your health care ever created tension between you and other people?

Question 8 For some people, the personal work of caring for their health condition can be emotionally challenging? Is this true for you? Are there any things that you do to “stay positive” or “keep your spirits up”?

Question 9 Has your health care affected you at all financially?

Question 10 Are there things that you routinely do to make management of your health condition easier?

Question 11 Is there anything else that you would like to tell me about today regarding your health conditions and how they are cared for?

Additional patient quotes

Theme 1: the work patients must do to care for their health

“I would say it is a full time job [managing diabetes]… So I would consider myself working at least two full time jobs” (41-year-old white male).

“And the days just seem to revolve around, making sure I get the insulin, making sure I get the meals on time… making sure that I am doing all the right things” (67-year-old white female).

Theme 2: problem-focused strategies and tools to facilitate the work of self-care

[Preparing medicines] “At home I have a pill cutter. I should start cutting up a whole week’s worth, but it is just a pain, I don’t do it other than when I have to… It is just time consuming to do” (36-year-old white male).

[Researching condition] “I keep up on all of the clinical studies and all the research that is going on, so I’m pretty up-to-date on that” (41-year-old white male).

“I do a lot of research on the Internet. And I have for this condition [atrial fibrillation], as well” (63-year-old white male).

Theme 3a: challenges with taking medication

[Side effects] “I’m not sleeping as well as I would like because of intolerance to pain medication (for fibromyalgia symptoms)” (61-year-old white female).

“Side effects, side effects, let’s hear side effects!.. the Elavil, I have a dry mouth, constipation, some dizziness… I don’t like being on this higher dose of Atenolol; I feel a little bit like I’m walking in a fog” (52-year-old white female).

[Interference with daily life] “Having to set my alarm is just an annoying daily thing when I don’t even have to get up; I have to set it because I have to take a pill” (26-year-old white male).

Theme 3c: role and activity limitations

[Social activity limitations] “And people wanted me to come and play bridge and to do other things, and I think, on the higher dose of the prednisone I feel tremulous and it is more difficult to concentrate” (66-year-old white female).

Theme 3d: financial challenges of health care

[Reimbursement] “Oh, it is a burden. Last year we used to be able to, anything that was a prescription, or even not a prescription, as long as your doctor said you need to take this; I could get reimbursed from my health care spending account. Now can’t do that anymore, prescription stuff only” (36-year-old white male).

Theme 3f: systemic obstacles of health care delivery

[Negative provider-patient relationship] “My neurologist, at times, asks a question and won’t listen to the answer and asks it again and won’t listen to the answer… so I have told him several times – you need to slow down and listen to me. And I mean that is pretty bold but, I mean he pisses me off ” (58-year-old white female).