Abstract

Background

The most frequent behavioral manifestations in Parkinson's disease (PD) are attributed to the dopaminergic dysregulation syndrome (DDS), which is considered to be secondary to the iatrogenic effects of the drugs that replace dopamine. Over the past few years some cases of patients improving their creative abilities after starting treatment with dopaminergic pharmaceuticals have been reported. These effects have not been clearly associated to DDS, but a relationship has been pointed out.

Methods

Case study of a patient with PD. The evolution of her paintings along medication changes and disease advance has been analyzed.

Results

The patient showed a compulsive increase of pictorial production after the diagnosis of PD was made. She made her best paintings when treated with cabergolide, and while painting, she reported a feeling of well-being, with loss of awareness of the disease and reduction of physical limitations.

Conclusions

Dopaminergic antagonists (DA) trigger a dopaminergic dysfunction that alters artistic creativity in patients having a predisposition for it. The development of these skills might be due to the dopaminergic overstimulation due to the therapy with DA, which causes a neurophysiological alteration that globally determines DDS.

Key words: Dopamine dysregulation, Parkinson's disease, Art

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is characterized by motor alterations, bradykinesia, resting tremors, cogwheel rigidity, postural changes, a progressive course, good response to the treatment with dopaminergic drugs [1] and psychological and behavioral symptoms [2, 3]. Some of them, like the depressive symptoms, are seen in 61% of the patients [2] and others, such as the manifestations of impulse control, are less frequent and generally appear in patients with early-onset PD and in patients treated with dopaminergic agonists (DA) [4, 5]. It is believed that depressive symptoms may be due to a serotoninergic dysfunction, although they have also been associated to the dopamine deficit [6]. The most frequent behavioral manifestations in PD, such as stereotypies, impulse control disorders, pathological gambling, hypersexuality, compulsive shopping and/or compulsive eating disorders are attributed to the dopaminergic dysregulation syndrome (DDS), which is considered to be secondary to the iatrogenic effects of the drugs that replace dopamine. DDS has been seen mainly in patients who use high doses of dopaminergic drugs over extended periods of time, and it is believed that they may be conditioned by genetic causes, personality traits and diseases associated to PD [7].

Although the modification of artistic attitudes and skills seen in some patients with PD have not been clearly associated to DDS, over the past few years, cases have been seen who, after starting treatment with dopaminergic drugs, improve their creative abilities, patients who have developed poetic skills [8], who have shown a compulsive increase of pictorial production [9, 10, 11] and who, while carrying out the artistic activity, state they perceive a feeling of well-being, with loss of awareness of the disease or even of their physical limitations [10]. In this sense, we present the case of a patient who has shown artistic skills and these feelings.

Clinical Course

We describe the case of a patient who is a nursing assistant, right-handed, without any medical history of interest, who has been a painting enthusiast since her youth, and whom we have followed for 20 years. At 54, she presented difficulty in writing and tremor in her right lower limb and was diagnosed with PD. She began an antiparkinsonian pharmacological treatment and remained nearly asymptomatic for seven years. After turning 61, her tremor increased and she began noting gait instability. At 62 she began falling down and started presenting with dyskinesia. At 63, her clinical symptoms worsened and she started presenting with difficulty walking, her dyskinesia increased and she suffered on/off episodes. From the age of 67, the ‘off’ moments caused great discomfort, and the changes in the pharmacological treatment did not control her discomfort, which is why she was finally forced to use a walker. In spite of the consecutive pharmacological changes, the motor difficulties worsened, the degree of dependence increased and she had to be admitted to a nursing home, which did not stop her from continuing painting.

In her early 70s, the motor disorders and the rigidity had increased, and six months later, dystonic movements appeared in her right lower limb. Pharmacological changes were carried out, with the introduction of rotigotine transdermal patches, and her clinical presentation continued worsening, with greater gait instability, dyskinesia and dystonic movements. The patient alternated using a walker and a wheelchair. At the age of 72, her dyskinesia continued and the rotigotine patches were replaced with ropirinole. Throughout the year, she fell down several times and frequently used the wheelchair to move around. At midyear, the doses of levodopa/carbidopa plus entacapone and ropirinole were reduced due to a lack of efficacy.

Currently, the patient continues living at the nursing home with the described limitations, without any tremors except at specific moments, with generalized rigidity, dystonic movements in the limbs, especially on the right limb, gait alterations and great instability. She uses the walker and the wheelchair. She continues painting, although less diligently. Table 1 shows the modification to the drugs and the evolution of her painting.

Table 1.

Medication (mg/24 h) of the patient from the age of 54 to 74 years

| Age | Benserazide/levodopa | Levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone | Amantadine | Selegiline | Ropirinole | Cabergoline | Rotigotine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54–60 | 125/500 | 5 | |||||

| 61 | 150/600 | 10 | |||||

| 62 | 150/600 | ||||||

| 63–65 | 150/600 | 300 | 6 | ||||

| 66 | 150/600 | 300 | 2 | ||||

| 67 | 125/500 | 2 | |||||

| 68–69 | 450/112.5/600 | 10 | |||||

| 70–71 | 75/300 | 450/112.5/600 | 8 | ||||

| 72 | 75/300 | 450/112.5/600 | 100 | 8 | |||

| 73–74 | 200/50/800 | 100 | 4 |

Assessment of the Creative Aspects of Her Work

Before the disease appeared, the patient produced works with a small format which were mostly drawings made with coloring pencils. During the first years of the disease, she was not intensely devoted to painting and only made drawings. From the age of 60, a greater interest awoke in her for artistic expression, and she became passionate for drawing, and later for painting. Painting relaxed her, and when she painted, she felt she was free from the disease. She stopped trembling and her motor control was excellent. She felt fulfilled and painted three or four days a week, for several hours. As her disease progressed, her artistic activity increased; drawing and painting brought great relief to her and, little by little, painting became her life's illusion. At first, it was difficult for her and her works were simple, mainly drawings with fine and regular strokes, without tremor, with clear lines and proportionate shadowing of little depth. The drawings were generally pencil drawings in which she emphasized on the first planes and neglected the background. In all of these, confident, neat, decisive strokes are noted, without tremors and with the same overall thickness. When she painted with colors, there was balance in the works and the figures were proportionate (fig. 1). As time went on, she progressively drifted from drawing and delved into other pictorial techniques, such as pastel, oil and water color. At the age of 63, 9 years after the diagnosis of the disease (treatment with ropirinole), her figures and her painting improved, the strokes were confident, without tremors, with vivacious and harmonious colors, although she was no longer concerned with perspective (fig. 2). Between 65 and 68 years of age (treatment with cabergolide), in spite of the disease worsening, it was probably the best artistic time of her life, the pictorial technique was more elaborate, and she used water colors only occasionally, now mainly painting with oil paints. Her works were simple, with great luminosity and well-contrasted colors and figures that easily attract the spectator. Her drawing style was still precise, using lines of different thicknesses, and she drew to highlight the essential features of the works that were, on occasions, carried out with great detail. From the age of 70, in spite of her condition worsening, she continued to maintain an interest for drawing and painting, and she painted, although with greater difficulty (she was being treated with rotigotine). The topics were simple, the tones were milder and she had the tendency to use warmer colors (fig. 3). During the years that followed, drawing predominated in her work, with irregular strokes that on occasions reflected tremor; the colors became less lively and the size of her pictures became smaller. Currently, in spite of the motor difficulties and the tremor that seriously affect her, she maintains her enthusiasm for painting, for finding that spiritual space that isolates her from her disease.

Fig. 1.

Painting 1 (1997; 60 years). Crayon drawing. Steady and sure hand, with no tremor. Colors are well balanced, and the figure is well proportioned. Close-up drawing, neglecting the background.

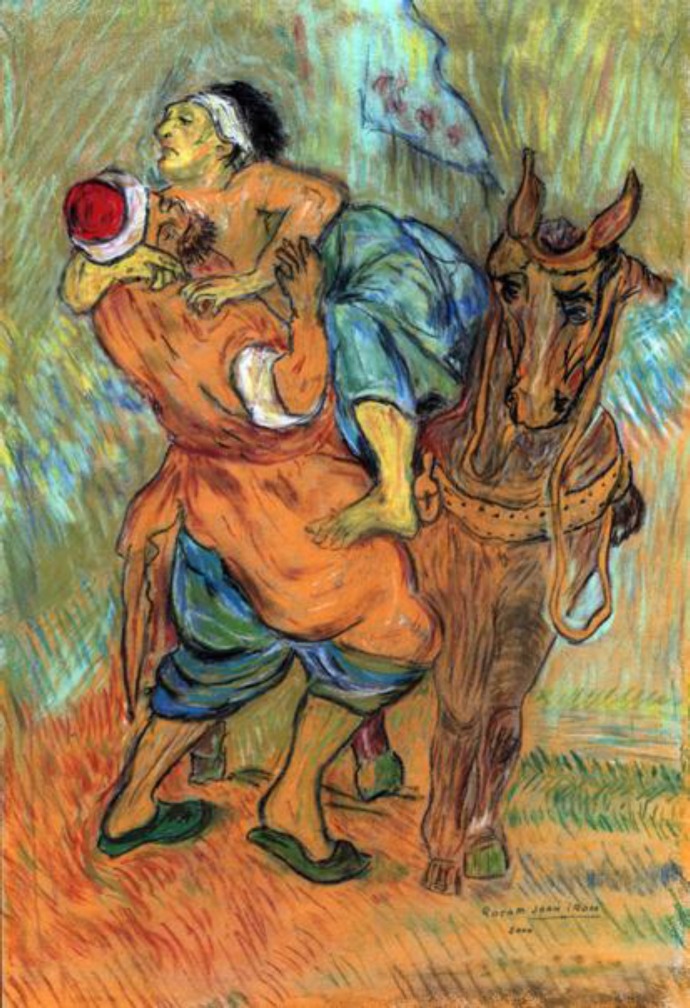

Fig. 2.

Painting 2 (2000; 63 years). Drawing in pastel. The figures appear outlined, with harmony in the colors used. Steady and sure hand, with no tremor.

Fig. 3.

Painting 3 (2009; 72 years). Watercolor. Different colors are used on a white background, regardless of the depth or the perspective of the figure.

Discussion

Our patient, as was the case with other painters who suffered PD, in spite of the tremor, the rigidity and the bradykinesia that affected her, especially the right side of her body, drew and painted, always with the right hand, and although her work varies in style, some of it is inspired in the work by other painters, such as Paul Gauguin or Salvador Dalí [10]. During the first years of the disease, she carried out mainly drawings of human figures, in pencil or charcoal, in which the neatness of the strokes, without retracing, the confidence in the lines that are never trembly, and the uniformity in the thickness and in the decisiveness stand out; these are qualities that remained throughout later work and that began to diminish after 15 years of disease. From that moment on, although the quality of the drawing was maintained, the confidence in the lines started dwindling, and occasional signs of tremor appeared, while the color palette was reduced and she kept to two or three tonalities that were denser and more obscure. Unlike what happened with other painters with PD, the style of her paintings was always realistic [10].

Throughout twenty years of disease, she remained in contact with painting ateliers, and even at moments of greater physical difficulty, she sought the way of commuting to these centers to be able to continue drawing and painting. Given the motor limitations of PD starting 10 years after the disease was diagnosed, the patient went to live at a nursing home, from which she commuted to the painting atelier in an electric wheelchair. The patient stated that when she drew or painted, she ‘felt she was drifting away from the world and had the feeling of setting herself free from the physical and psychic burdens of the disease’. This feeling of personal achievement, of release and physical and emotional control, is similar to the one described by another painter with PD, who stated that while she painted, she had the feeling of entering a Zen state, ‘being in front of a white paper and material that was prepared for painting induced in her a state of mental calmness that overcame the imperfections of her personal life and produced a sensation of spiritual peace she noted in herself, and that she perceived was transmitted to the people who were with her’. Both patients developed their pictorial activity from the beginning of the symptoms of the disease, and they asked themselves if having started painting foretold the onset of PD, or if it were possible that their disease and the drugs had contributed to the artistic creativity that they manifested throughout the process.

Artistic creativity is not exclusively a technical or theoretical matter, but rather, it expresses the way in which the author conceives and executes his/her work in the context of his/her personality and sensitivity [11]. In most cases described of patients with PD who are painters, the disease modified the artistic activity and their work acquired a greater relevance in a certain period of their lives. Our patient was more prolific between the age of 63 and 72 years, and her paintings improved in color and balance. At 66, she had an exhibit of the work she produced between 63 and 66 years of age, the period of greatest artistic activity that coincided with pharmacological changes, although the treatment with benserazide/levodopa was not modified, and the dopaminergic agonist that she had been taking since the beginning of the disease was replaced, leaving selegiline for ropirinole. Different authors have described changes in the artistic activity of patients with PD in which, after having introduced or modified regimens with dopaminergic agonists, they considered there was an improvement in their artistic skills, the quality and the amount of works. The therapy with dopaminergic agonists has been considered responsible for achieving a regulation in the dopaminergic stimulation that would give rise to the emotional changes that would, in turn, allow these patients an improved perception of the visual-perceptive ability; this would explain the changes in the painting styles seen that translate into a better technique and a better balance of the tonality and luminosity of the works [10].

As for our patient, albeit not as evidently as with other cases, from the moment in which the dopaminergic agonist medication was administered, and during the time she took it, she modified her interest for painting, which became her primordial activity; it modified her emotional state and her creative skills, manifesting a change in the perceptive ability and in artistic skills, going from figurative compositions to nature paintings, and modifying the luminosity and coloring of her work.

Our patient's creativity was not associated to levodopa, as her best years of creativity arose with the introduction of dopamine agonists, while we believe that the progressive loss in creative aspects and in the quality of her work over the last few years was more associated to the condition worsening than to the effect of these drugs. In any case, we do not rule out the possibility of the progressive loss of creative skills over the past few years, which contrasts the creative emergence of the start of the treatment with agonist medications and that could have stimulated her to paint, may have been lost over time, being in great measure due to the doses of the agonist drugs in these past few years being very reduced. Therefore, it is possible that, as other authors have noted, the loss of artistic skills is due to the medication doses being inadequate to maintain creative stimulation, and that in our patient, they had already been reduced from the start to avoid producing dyskinesia and hallucinations.

The creative activity seen in some patients with PD has been associated to an increase in dopamine levels in frontal-subcortical circuits that connect the medial prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, the limbic system and the ventral striatal system [12]. This may be true; however, in order to explain cases as that of our patient, there must be an individual attitude that we have also seen in another patient who we followed for several years who kept a great artistic activity throughout the course of the disease, and when he was treated with rotigotine or pramipexol, at very low doses, he showed behavioral changes and compulsive gambling, a fact that coincided with an improvement in the pictorial activity and quality [13].

Like other authors, we think that in some cases, patients with PD who are administered dopaminergic drugs may suddenly develop a creative activity they had not had before, because they already had a predisposition for it (painting, modelling, sculpturing, writing novels or poetry). These drugs trigger a dopaminergic dysfunction that conditions the development of not only the artistic activity, but also the way they conceive other aspects of their daily life. The artistic skills after the dopaminergic treatment, as occurred in our patient, are developed based on a prior individual substrate for artistic dexterities that was already established and that started to emerge when the dopaminergic overstimulation, secondary to the therapy with dopaminergic drugs, was produced [14]. The similarity of this activity in our patient with that seen among patients with artistic skills and in others with other types of psychological behavioral manifestations that were seen after administering DA, lead us to think that the development of these skills is due to the neurophysiological alteration itself that globally conditions DDS [15].

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the generous collaboration of the patient Rosa Ma Joan i Rosa, and her family.

References

- 1.Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go CL, Rosales RL, Joya-Tanglao M, Fernández HH. Untreated depressive symptoms among cognitively-intact, community dwelling Filipino patients with Parkinson disease. Int J Neurosci. 2011;121:137–141. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2010.537414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piacentini S, Versaci R, Romito L, Ferré F, Albanese A. Behavioral and personality features in patients with lateralized Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:772–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambermoon P, Carter A, Hall WD, Dissanayaka NN, O'Sullivan JD. Impulse control disorders in patients with Parkinson's disease receiving dopamine replacement therapy: evidence and implications for the addictions field. Addiction. 2011;106:283–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bharmal A, Lu C, Quickfall J, Crockford D, Suchowersky O. Outcomes of patients with Parkinson disease and pathological gambling. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:473–477. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100010489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beucke JC, Uhl I, Plotkin M, Winter C, Assion HJ, Endrass T, Amthauer H, Kupsch A, Juckel G. Serotonergic neurotransmission in early Parkinson's disease: a pilot study to assess implications for depression in this disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11:781–787. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2010.491127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Sullivan SS, Evans AH, Lees AJ. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome: an overview of its epidemiology, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:157–170. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schrag A, Trimble M. Poetic talent unmasked by treatment of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1175–1176. doi: 10.1002/mds.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker RH, Warwick R, Cercy SP. Augmentation of artistic productivity in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21:285–286. doi: 10.1002/mds.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chatterjee A, Hamilton RH, Amorapanth PX. Art produced by a patient with Parkinson's disease. Behav Neurol. 2006;17:105–108. doi: 10.1155/2006/901832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laneyrie-Dagen N: Leer la pintura. Editorial Larousse, 2006; pág. X-XI.

- 12.Lawrence AD, Evans AH, Lees AJ. Compulsive use of dopamine replacement therapy in Parkinson's disease: reward systems gone awry? Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:595–604. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00529-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López-Pousa S. Creatividad pictórica en la demencia asociada a la enfermedad de Parkinson. Alzheimer Real Invest Demenc. 2012;50:20–29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canesi M, Rusconi ML, Isaias IU, Pezzoli G. Artistic productivity and creative thinking in Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:468–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwingenschuh P, Katschnig P, Saurugg R, Ott E, Bhatia KP. Artistic profession: a potential risk factor for dopamine dysregulation syndrome in Parkinson's disease? Mov Disord. 2010;25:493–496. doi: 10.1002/mds.22936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]