Abstract

Background:

Soy milk replacement in the diet might have beneficial effects on waist circumference and cardiovascular risk factors for overweight and obese subjects. Therefore, we are going to determine the effects of soy milk replacements on the waist circumference and cardiovascular risk factors among overweight and obese female adults.

Methods:

In this crossover randomized clinical trail, 24 over weight and obese female adults were on a diet with soy milk or the diet with cow's milk for four weeks. In the diet with soy milk only one glass of soy milk (240 cc) was replaced instead of one glass of cow's milk (240 cc). Measurements were done according to the standard protocol.

Results:

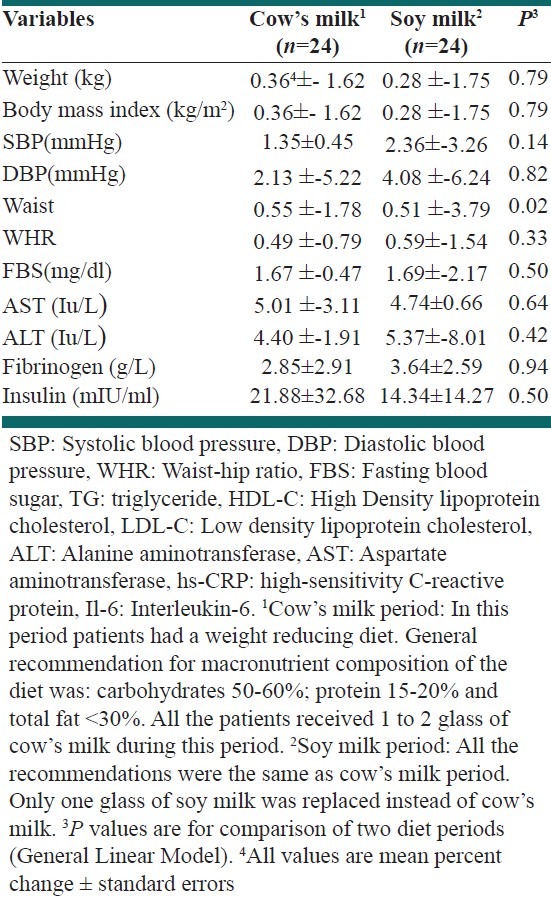

Waist circumference reduced significantly following soy milk period (mean percent change in soy milk period for waist circumference: -3.79 ± 0.51 vs. -1.78 ± 0.55 %; P = 0.02 in the cow's milk period). Blood pressure, weight, liver enzymes and glycemic control indices did not changed significantly after soy milk period compared to the cow's milk period.

Conclusion:

Among over weight and obese patients, soy milk can play an important role in reducing waist circumference. However, soy milk replacement had no significant effects on weight, glycemic control indices, liver enzymes, fibrinogen and blood pressure in a short term trial.

Keywords: Obese, overweight, soymilk

INTRODUCTION

One of the major health concerns worldwide is obesity and overweight.[1] Prevalence of obesity and central adiposity has increased both in developed[2] and in developing countries.[3–5] Obesity can result in other chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases.[1] There is a close relationship between obesity, overweight and cardio-metabolic risks.[6] In addition, obesity causes chronic inflammation disorder and increment of blood fibrinogen level and it results in insulin resistance development and cardiovascular diseases.[7,8] Serum levels of aminotransferases also are elevated among overweight and obese patients and are associated with the development of cardiovascular risk and glycemic control abnormalities.[9] Recent studies have shown that elevated levels of liver enzymes are correlated with diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.[9]

There are several environmental factors associated to central and general obesity.[10,11] Dietary intakes is one of the important associates of overweight and both central and general adiposity.[12] Different diet therapies are recommended regarding the treatment of overweight and obesity.[13,14] Soy products contain some components which affect on some cardiovascular risks.[15–17] Major researches had focused on the effects of soy beans or soy proteins or soy nuts and few of them had considered the soy milk. Recent published papers show that whole soy consumption is better than only soy components.[18] Soy milk is one of the soy products which contains all the useful components of soy. Soymilk components such as isoflavones, essential fatty acids, phytosterols, good fats, inositols might have beneficial effects on weight control and blood pressure management.[18,19] However, few studies focused on the effects of soy milk on weight reduction or cardiovascular risks. A recent clinical trial revealed that soy milk consumption had the lowest effect on weight reduction compared to cow's milk or calcium supplements.[20] There are few studies regarding the effects of soymilk consumption on fibrinolytic factors, glycemic control and the liver enzymes level among non-postmenopausal female adults. Previous studies are mostly focus on postmenopausal, premenopausal women and patients but there are few studies on young female adults and overweight or obese subjects. Therefore, we are going to determine the effects of soymilk consumption on the waist circumference and cardiovascular risks among non-menopausal overweight and obese female adults.

METHODS

Participants

Patients in the age range of 20 to 50 years diagnosed with overweight and obese were eligible for the present study. Having allergy to soy product or cow's milk, occurrence of chronic or critical diseases which make patients not to follow the research protocol or initiating to consume the medications and also not following the research protocol were the exclusion criteria. Of the patients invited to participate, 2 patients did not meeting inclusion criteria and 3 subjects refused to participate. In total, 30 patients enrolled in the study.

The sample size of the research was calculated based on the formula suggested for cross-over trials[21]: n= [(Z(1-α) + Z(1-β))2. S]/2Δ2; where α (type 1 error) was 0.05, β (type 2 error) was 0.10, S (the variance of CRP) was 0.1 and Δ (the difference in mean of CRP) was 0.2. We considered CRP as the principal variable. The research by Azadbakht et al.[21] was used to calculate the mean and variance of CRP: n = [(1.96 + 1.28)2. (2)2]/2 (1)2 = 13. Therefore, according to the formula, 13 patients were needed for sufficient power.

30 subjects were volunteers, to take part in the study. It was found that all of subjects had BMI more than 25 kg/m2, after measuring weight and height and calculating BMI. They had all of the initiate criteria and no specific problem was found in their biochemical blood test records. Informed written consent was signed by all the participants. This research was supported by the research council and ethics committee of Food Security Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Nutrition Department, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Science in Iran. This research has been registered in the http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (ID number NCT01253876) and http://www.irct.ir (ID number IRCT201107052839N3). We followed the consort statement in writing this clinical trial.

Study procedures

This was a cross-over randomized clinical trial, which was conducted on non-menopausal overweight or obese females. After two weeks run-in, subjects were randomly chosen to consume a diet containing cow's milk or a diet containing soy milk. The trial phase was four weeks for each one. For classified females in different group, random sequencing generated in SPSS was used. As this was a dietary intervention, it was not blind. Patients were prescribed to consume diet with soy milk in one period of trial and use diet with cow's milk in another period. Each subject had two diets. Each patient spent two weeks of wash-out period. All patients were on a weight reducing diet. The diet was prescribed for patients and they prepared their own meals. Only soy milks and cow's milk were prepared for each subject. All the patients were asked not to change their usual physical activity during the study.

Diets

Two diets were given to each patient: 1) diet with cow's milk and 2) diet with soy milk. Both diets consisted of macronutrient composition as 50-60% carbohydrates, 15-20% protein, <30% total fat.

The suggested equations by Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board were used to calculate the required calorie of each female adults.[22] We reduced 200 to 500 kcal/day for each patient considering her BMI range in both periods. In diet with soy milk, one glass of soy milk (240 cc) was replaced instead of one glass of cow's milk (240 cc). We gave each patient an individual diet and an exchange list for using during the study period. Then subjects recorded their food intake.

Patients were visited every two weeks and their adherence was checked by analysis of the three-day food diaries at baseline and end of each trial. Macronutrients and servings of different food group intake separately in each dietary period measurement. We did not find any differences between the prescribed amount and reported dietary intake of the five food groups.

Measurements

We measured subject's weight by digital scales to the nearest 0.1 kg with minimal cloths and without any shoes. Height was measured in a standing position, without shoes, using a measuring tape. Waist circumference (WC) was measured to the nearest 0.1, in the place where the waist was narrowest over light clothing by a non-stretchable tape measure, without applying pressure to the body surface. Hip circumference was measured in the largest part of the hip over light clothing. Blood pressure was measured three times after the participants sat for 15 min. Then, we reported the mean of the three times measurement. Blood samples were collected after 12h of fasting overnight. We used two separate tubes for storing sodium citrate buffers for plasma and serum. We centrifuged the tubes at 4°C and 500 × g for 10 min. We did the test at the same day and for impossible test, plasma samples were frozen promptly (-70°C). We measured fasting blood sugar by an enzymatic colorimetric method. In this measurement, we used kit of Pars Azmoon, Iran. Insulin and serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured by commercially available enzymatic reagents (Pars Azmoon, Iran) on a BT-3000 (Biotechinica) autoanalyzer. Inter-and intra-assay coefficients of variation were both <5%. We used standard and control solutions and standard curves were plotted for all of standardized measurements. Clauss method[23] was considered for measuring plasma fibrinogen level, which quantitatively determines the concentration of fibrinogen by adding thrombin and recording the rate of fibrinogen conversion to fibrin. We made lad blinded for all treatment status.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the dietary intake with N4. For comparing means of the all variables at the end of the two different diet periods we used paired t-tests. The percent change for each variable was calculated by the formula (E-B/B) ×100. E was the end of treatment value and B was the baseline value. By using paired t test analyses the percent changes of all variables were compared between two groups. By using the appropriate General Linear Model period effect and treatment order effects were tested.

All results were significant if the two-tailed P value was <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS for Windows (version 13.0 SPSS), Chicago IL.

RESULTS

Of the 30 participants, 24 overweight and obese female adults completed the entire cross-over study. During the study, two patients could not continue the study due to case of digestive problem. One of them envisages a problem in blood testing. Three females did not follow the protocol and thus, their data were not available.

The mean age and BMI of the patients were 37.7 ± 1.3 years and 30.8 ± 0.8 kg/m2, respectively. No one was smoker and none of them on specific medications.

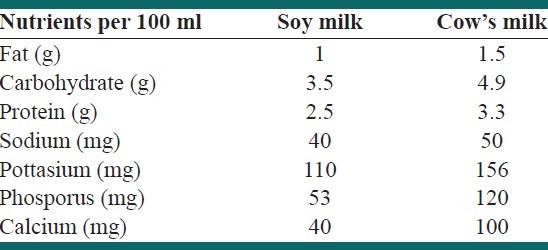

Composition of soy milk and cow's milk consumed by the participants of the present study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of soy milk and cow's milk consumed by the participants of the present study

Macronutrients and servings of different food group intake in each dietary period were analyzed. It is shown in Table 2. They did not changed significantly after soy milk period compared to the cow's milk period.

Table 2.

Macronutrients and servings of different food group intake separately in each dietary period

Participant's activity levels remained the same during the entire study period. The baseline and end of trial values regarding cardiovascular risk factors are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison the baseline and end of trial between two groups regarding waist circumference and cardiovascular risk factors

Except the end values of the two groups for waist circumference (P = 0.02) there were no significant differences between two groups regarding other cardiovascular risk factors at baseline and at the end of the study.

Mean percent changes in waist circumference and cardiovascular risk factors are presented in Table 4. No significant changes were appeared regarding the cardiovascular variables. Waist circumference reduced significantly after soy milk replacement in the diet.

Table 4.

Mean percent changes in waist circumference and cardiovascular risk factors level separately by each trial period (Cow's milk and Soy milk)

DISCUSSION

The results of the present research which was conducted on non-menopausal overweight and obese female adults, showed a reduction in waist circumference following four weeks consumption of soy milk. We found that soy milk replacement in the diet had no significant effect on weight, blood pressure, liver enzymes, glycemic control and serum fibrinogen level among overweight or obese female adults. Previous studies regarding the effects of soy had focused on premenopausal and post menopausal women or patients. However, few studies are available on the female adults or overweight or obese subjects.

Soy milk replacement did not enhance weight loss but provided waist circumference reduction. Previous researches showed no significant changes on weight with different soy products in Iran.[24–27] Therefore, the beneficial components in soy products could be effective on cardiometabolic and cardiorenal abnormalities independent of weight change.[24–27] A six weeks trial by soy drinks showed beneficial effects on weight and waist circumference reduction in 90 overweight and obese subjects.[28] The results of this short time trial was same as some study which had not shown beneficial effects of soy product on weight. Most researches which shown positive effects in this regard worked on animals or larger number of subjects in longer time trials.[28–32] In this study, waist circumference reduction may be related to soy milk phytoesterogen content and soy milk protein which may play an important role on reducing fat accumulation.[33] This might be related to a soy protein like Beta conglycinin.[34] The results of this study is similar to Sites study. In both two researches waist circumference reduced without any changes in weight.[17]

Some soy contents like polyphenols have beneficial influences on controlling blood pressure.[19] Following soy product consumption, serum nitric oxide level increases and blood pressure reduces.[35] Some studies showed no relation between soy product consumption and blood pressure.[15] Soy isoflavones had beneficial effects on blood pressure in hypertensive subjects but no significant result in normotensive subjects.[36] Soy isoflavones might act like estrogens, especially in postmenopausal women who have low endogenous estrogen levels.[37] In this study, soy milk replacement did not affect on blood pressure. This result may be related to conducting research on normotensive and non-menopausal subjects.

We were unable to find significant differences between diet with soy milk and diet with cow's milk with regard to glucose and insulin metabolism in our study. Similar to our findings, Villa and colleagues found no difference in glycemic control indices between genistein and placebo[38] In contrast, Jayagopal and colleagues reported that in postmenopausal type 2 diabetics, soy supplementation resulted in significant decreases in insulin.[39] It is possible that the effects of soy isoflavones on glycemic control indices vary depending on the glycemic status of the individual.[40]

Fibrinogen is a glycoprotein, the plasma component of which is synthesized in the liver. Fibrinogen is changed by thrombin to output fibrin monomers that are the primary constituent of the fibrin clot.[41] Increased plasma fibrinogen levels have been clearly connected with an increase in risk of cardiovascular disease, including ischemic heart disease, stroke, and other thromboembolic events, because increased fibrinogen levels enhance thrombus forming by altering the kinetics of the coagulation cascade, resulting in increased fibrin forming, increased platelet aggregation, and increased plasma stickiness.[42–44] There is no evidence for the effects of soy milk on Fibrinogen in previous studies. We did not find any effect of soy milk on fibrinogen levels in this study.

Comparing the two diets with soy milk and cow's milk showed that serum ALT and AST had no significant reduction during the diet with soy milk. Previous studies have shown that higher liver enzyme levels are related to higher risk of cardiovascular diseases.[9] Furthermore, serum liver enzyme levels are considered as new cardiovascular risk factors and they are associated with glycemic control abnormalities.

Most studies have focus on only some components of soy and there are few researches on all parts of the soy and whole soy. Recent researches indicate higher positive effects from complete forms such as soybean[45] and soy milk.[18] It sound that combination of soy protein, fatty acids, and phytoestrogens together are more effective than the isolated soy, purified phytoestrogens and protein alone.[46]

A positive point of this research was cross-over design for conducting this trial. Our trial should have good external validity, since this study was conducted on a sample of non-menopausal overweight or obese female adults with no special disorder.

Limitations of the study

We did not prepare food for each patient except soy milk and cow's milk. This limitation should be considered in explaining the results. What the female adults ate was controlled by analyzing the dietary intake of patients’ food records. The results indicated that soy milk could have beneficial effects on waist circumference, despite the diet in our study may not be followed as carefully as the trials which prepared food was available.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Food Security Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences supported this research. The writers appreciate the cooperation of Cardiovascular Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for providing facilities to do the biochemical experiments. We also respect the cooperation of all the female adults of this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin LG, Schoeni RF, Andreski PM. Trends in health of older adults in the United States: Past, present, future. Demography. 2010;47:S17–40. doi: 10.1353/dem.2010.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murakami Y, Miura K, Ueshima H. Comparison of the trends and current status of obesity between Japan and other developed countries. Nippon Rinsho. 2009;67:245–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azizi F, Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P. Trends in overweight, obesity and central fat accumulation among Tehranian adults between 1998-1999 and 2001-2002: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Ann Nutr Metab. 2005;49:3–8. doi: 10.1159/000084171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janghorbani M, Amini M, Willett WC, Mehdi Gouya M, Delavari A, Alikhani S, et al. First nationwide survey of prevalence of overweight, underweight, and abdominal obesity in Iranian adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2797–808. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Shiva N, Azizi F. General obesity and central adiposity in a representative sample of Tehranian adults: Prevalence and determinants. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2005;75:297–304. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.75.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Parise H, Sullivan L, Meigs JB. Metabolic Syndrome as a Precursor of Cardiovascular Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation. 2005;112:3066–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.539528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L. Increased levels of inflammation among women with enlarged waist and elevated triglyceride concentrations. Ann Nutr Metab. 2010;57:77–84. doi: 10.1159/000318588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen XM, Lane J, Smith BR, Nguyen NT. Changes in inflammatory biomarkers across weight classes in a representative US population: A link between obesity and inflammation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1205–12. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0904-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato KK, Hayashi T, Nakamura Y, Harita N, Yoneda T, Endo G, et al. Liver enzymes compared with alcohol consumption in predicting the risk of type 2 diabetes: The Kansai Healthcare Study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1230–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostrowska L, Karczewski J, Szwarc J. Dietary habits as an environmental factor of overweight and obesity. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2007;58:307–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagou V, Liu G, Zhu H, Stallmann-Jorgensen IS, Gutin B, Dong Y, et al. Lifestyle and Socioeconomic-Status Modify the Effects of ADRB2 and NOS3 on Adiposity in European-American and African-American Adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:595–603. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A. Dietary and non-dietary determinants of central adiposity among Tehrani women. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:528–34. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bol’shova OV, Malinovs’ka TM. Diet therapy of obesity in children and adolescents. Lik Sprava. 2008;(7-8):70–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szyguła Z, Pilch W, Borkowski ZL, Bryła A. The influence of diet and physical activity therapy on the body's composition of medium obesity women and men. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2006;57:283–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthan NR, Jalbert SM, Ausman LM, Kuvin JT, Karas RH, Lichtenstein AH. Effect of soy protein from differently processed products on cardiovascular disease risk factors and vascular endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:960–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nasca MM, Zhou JR, Welty FK. Effect of soy nuts on adhesion molecules and markers of inflammation in hypertensive and normotensive postmenopausal women. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:84–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sites CK, Cooper BC, Toth MJ, Gastaldelli A, Arabshahi A, Barnes S. Effect of a daily supplement of soy protein on body composition and insulin secretion in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:1609–17. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinwald S, Akabas SR, Weaver CM. Whole versus the piecemeal approach to evaluating soy. J Nutr. 2010;140:2335S–43. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.124925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galleano M, Pechanova O, Fraga CG. Hypertension, nitric oxide, oxidants, and dietary plant polyphenols. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2010;11:837–48. doi: 10.2174/138920110793262114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faghih S, Abadi AR, Hedayati M, Kimiagar SM. Comparison of the effects of cows’ milk, fortified soy milk, and calcium supplement on weight and fat loss in premenopausal overweight and obese women. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;21:499–503. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azadbakht L, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Esmaillzadeh A, Hu FB, Willett WC. Soy consumption, markers of inflammation, and endothelial function: A cross-over study in postmenopausal women with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:967–73. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trumbo P, Schlicker S, Yates AA, Poos M. Institute of Medicine, Food and nutrition board. Dietary Reference intake for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids, Washington DC. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1621–30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azadbakht L, Surkan PJ, Esmaillzadeh A, Willett WC. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension eating plan affects C-reactive protein, coagulation abnormalities, and hepatic function tests among type 2 diabetic patients. J Nutr. 2011;141:1083–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.136739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azadbakht L, Atabak S, Esmaillzadeh A. Soy protein intake, cardiorenal indices, and C-reactive protein in type 2 diabetes with nephropathy: A longitudinal randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:648–54. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azadbakht L, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Esmaillzadeh A, Hu FB, Willett WC. Dietary soya intake alters plasma antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in postmenopausal women with the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:807–13. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507746871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azadbakht L, Shakerhosseini R, Atabak S, Jamshidian M, Mehrabi Y, Esmaillzadeh A. Beneficiary effect of dietary soy protein on lowering plasma levels of lipid and improving kidney function in type II diabetes with nephropathy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:1292–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A. Effect of soy consumption on the serum leptin level among postmenopausal women. J Res Med Sci. 2010;15:317–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheik NC, Rossi EA, Guerra RL, Tenório NM, Oller do Nascimento CM, Viana FP, et al. Effects of a ferment soy product on the adipocyte area reduction and dyslipidemia control in hypercholesterolemic adult male rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frigolet ME, Torres N, Uribe-Figueroa L, Rangel C, Jimenez-Sanchez G, Tovar AR. White adipose tissue genome wide-expression profiling and adipocyte metabolic functions after soy protein consumption in rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22:118–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torre-Villalvazo I, Gonzalez F, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Tovar AR, Torres N. Dietary soy protein reduces cardiac lipid accumulation and the ceramide concentration in high-fat diet-fed rats and ob/ob mice. J Nutr. 2009;139:2237–43. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.109769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaughn N, Rizzo A, Doane D, Beverly JL, Gonzalez de Mejia E. Intracerebroventricular administration of soy protein hydrolysates reduces body weight without affecting food intake in rats. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2008;63:41–6. doi: 10.1007/s11130-007-0067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.König D, Deibert P, Frey I, Landmann U, Berg A. Effect of meal replacement on metabolic risk factors in overweight and obese subjects. Ann Nutr Metab. 2008;52:74–8. doi: 10.1159/000119416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cederroth CR, Nef S. Soy, phytoestrogens and metabolism: A review. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;304:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez-Villaluenga C, Bringe NA, Berhow MA, Gonzalez de Mejia E. Beta-conglycinin embeds active peptides that inhibit lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:10533–43. doi: 10.1021/jf802216b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simão AN, Lozovoy MA, Simão TN, Dichi JB, Matsuo T, Dichi I. Nitric oxide enhancement and blood pressure decrease in patients with metabolic syndrome using soy protein or fish oil. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;54:540–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302010000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu XX, Li SH, Chen JZ, Sun K, Wang XJ, Wang XG, et al. Effect of soy isoflavones on blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;22:463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagata C, Shimizu H, Takami R, Hayashi M, Takeda N, Yasuda K. Association of blood pressure with intake of soy products and other food groups in Japanese men and women. Prev Med. 2003;36:692–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villa P, Costantini B, Suriano R, Perri C, Macrì F, Ricciardi L, et al. The Differential Effect of the Phytoestrogen Genistein on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Postmenopausal Women: Relationship with the Metabolic Status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;94:552–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jayagopal V, Albertazzi P, Kilpatrick ES, Howarth EM, Jennings PE, Hepburn DA, et al. Beneficial effects of soy phytoestrogen intake in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1709–14. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christie DR, Grant J, Darnell BE, Chapman VR, Gastaldelli A, Sites CK. Metabolic effects of soy supplementation in postmenopausal Caucasian and African American women: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:153.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chandler WL, Rodgers GM, Sprouse JT, Thompson AR. Elevated hemostatic factor levels as potential risk factors for thrombosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:1405–14. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-1405-EHFLAP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Visser MC, Poort SR, Vos HC, Rosendaal FR, Bertina RM. Factor X levels, polymorphisms in the promotor region of factor X, and the risk of venous thrombosis. Thrmob Haemost. 2001;85:1011–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frishman WH. Biologic markers as predictors of cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 1998;104:18S–27. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kannel WB. Overview of hemostatic factors involved in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Lipids. 2005;40:1215–20. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1488-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shidfar F, Ehramphosh E, Heydari I, Haghighi L, Hosseini S, Shidfar S. Effects of soy bean on serum paraoxonase 1 activity and lipoproteins in hyperlipidemic postmenopausal women. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2009;60:195–205. doi: 10.1080/09637480701669463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cassidy A, Brown JE, Hawdon A, Faughnan MS, King LJ, Millward J, et al. Factors affecting the bioavailability of soy isoflavones in humans after ingestion of physiologically relevant levels from different soy foods. J Nutr. 2006;136:45–51. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]