Abstract

Study design: Systematic review.

Study rationale: While magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used as the diagnostic gold standard for cauda equina syndrome (CES), many MRI scans obtained from patients presenting with signs and/or symptoms of CES do not reveal concordant pathology. As a result, the role of the history and physical examination remains unclear when determining which patients require emergent MRI.

Objective or clinical question: Are there elements from the history or physical examination that are associated with CES as established by MRI?

Methods: A systematic review of the literature was undertaken for articles published through April 13, 2011. PubMed, Cochrane, National Guideline Clearinghouse Databases, and bibliographies of key articles were searched. Two independent reviewers reviewed articles. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were set and each article was subject to a predefined quality-rating scheme.

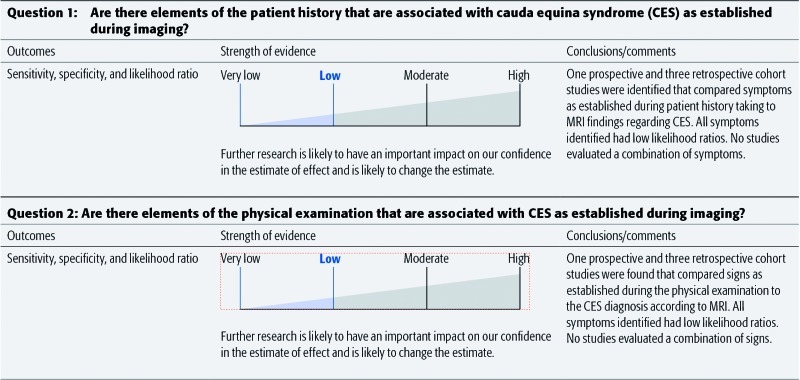

Results: We identified four articles meeting our inclusion criteria. All studies evaluated patients with symptoms suggestive of CES and compared symptoms and/or signs with findings at MRI. The mean prevalence of CES as diagnosed by MRI ranged from 14%–48% of patients. No symptoms or signs reported by more than one study showed high sensitivity and specificity, and all likelihood ratios were low. Symptoms included back/low back pain, bilateral sciatica, bladder retention, bladder incontinence, frequent urination, decreased urinary sensation, and bowel incontinence; signs included saddle numbness and reduced anal tone.

Conclusions: There is low evidence that individual symptoms or signs from the patient history or clinical examination, respectively, can be used to diagnose CES. Additional prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether any single and/or combination of symptoms are associated with a positive diagnosis of CES.

Study Rationale and Context

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is often defined by a broad range of symptoms and physical examination findings: back pain, leg pain, weakness, numbness, and bowel or urinary changes. However, many of these symptoms may also be caused by medications, nonspinal pathology, or by spine diseases that can be treated nonemergently.

Cauda equina syndrome is one of the most commonly litigated diagnoses with medicolegal concerns regarding the impact of a missed or delayed diagnosis. Given the lack of clearly defined symptoms and signs as well as the legal risks associated with perceived delays in diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is frequently obtained in patients presenting with these symptoms.

While MRI, coupled with patient history and examination, remains the diagnostic gold standard, it comes at a high cost with many patients demonstrating no concordant pathology. Given the need to accurately diagnose CES while balancing the cost of diagnosis, the role of patient history and physical examination needs to be clarified.

There is a problem of “true diagnosis” here in that CES is only really established when treatment has failed. At presentation with symptoms and signs of CES, not all subjects have CES (perhaps 40% in terms of MRI). At investigation (usually MR) a judgment has to be made if there is cauda equina decompression that might be relieved by surgery. Surgical success is if there are no residual symptoms, but there cannot be complete certainty that this would not have happened by natural resolution. Surgical failure is CES. We have chosen to use MR as the gold standard since it is at this stage that a surgical solution has to be planned and executed.

Clinical Question

Are there elements of the patient history or physical examination that are associated with CES as established during imaging?

Methods

Study design: Systematic review.

Sampling: PubMed, Cochrane Collaboration Database, bibliographies of key articles. Dates searched: through April 13, 2011.

Inclusion criteria: (1) adults presenting with clinical features suggestive of CES; (2) diagnostic studies evaluating elements from patient history (symptoms) and/or from the physical examination (signs); (3) diagnostic imaging (MRI, CT, or myelography) or findings at surgery as the gold standard.

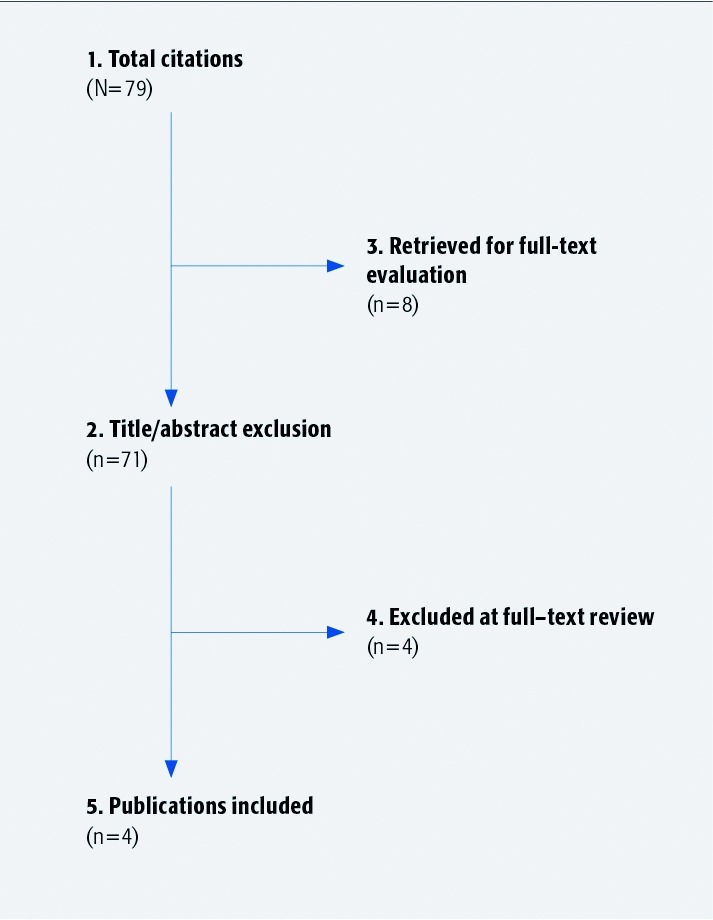

Exclusion criteria (Fig. 1): (1) patients < 18 years old; (2) patients with trauma, inflammatory cause, spondylolisthesis, Paget disease, osteochondrosis, congenital malformation, visceral diseases, or cancer; (3) confirmed CES in all patients; (4) gold standard used is composite of surgery or imaging with index test; and (5) therapeutic studies.

Fig. 1.

Results of literature search.

Elements from history and physical examination:

Symptoms

Back pain

Leg pain/sciatica

Neurological symptoms (weakness; bowel or bladder)

Aggravating factors

Alleviating factors

Signs

Neurological examination (motor or sensory)

Reflexes

Rectal tone

Outcomes:

Prevalence of CES according to MRI findings

Summary of sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios for symptoms and signs reported by more than one study

Analysis: Prevalence, sensitivities, specificities, and likelihood ratios were recorded or calculated from the available data. Overall strength of the evidence was assessed using GRADE criteria.

Additional methodological and technical details are provided in the Web Appendix at www.aospine.org/ebsj

Results

From 77 citations, 8 underwent full-text review. Four1,2,3,4 met the inclusion criteria (Table 1): 1 prospective (LoE-III)2 and 3 retrospective (LoE-IV) studies.1,3,4 (See Table 2 of the Web Appendix).

Patients with suspected CES underwent diagnostic MRI (Table 1, Web appendix), mean prevalence CES: 14%–48% (Tables 3–4, Web Appendix).1,2,3,4

Table 1. Patient and treatment characteristics of included studies investigating diagnostic accuracy of elements of patient history or physical examination compared with imaging or findings at surgery.*.

| Author | Study design (LoE) | Demographics | Symptoms/patient history | Signs/physical examination | Reference standard; criteria positive CES diagnosis | Study objective; inclusion/exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Balasubramanian et al;1 (2010) Domen et al,3 (2009) |

Retrospective diagnostic study | N = 80 Male: NR Mean age: NR (range, 21–90 y) (57% in 4th and 5th decades) |

|

|

MRI Details of lumbar MRI scans:

|

Objective

|

| Bell et al2 (2007); Balasubramanian et al1 (2010) | Prospective diagnostic study | N = 23 Male: 61% Mean age: 39 (range, 17–59) y |

|

|

MRI Details of lumbar MRI scans:

|

Objective

|

| Domen et al3(2009); Bell et al,2 2007 | Retrospective diagnostic study | N = 58 Male: NR Mean age: NR |

|

|

MRI Details of lumbar MRI scans:

|

Objective

|

| Rooney et al4 (2009); Domen et al3 (2009) | Retrospective diagnostic study | N = 98† Male: 27% (18/66)† Mean age: 43 y |

|

|

MRI Details of lumbar MRI scans:

|

Objective

|

CES indicates cauda equina syndrome; NR, not reported; and MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Complete records available for 66 of 98 patients, the remaining 22 were excluded; all data reported for n = 66 patients with complete records.

Symptoms (Table 3)

Back pain and bowel incontinence1,2,3,4 had high sensitivities, low specificities, and low LRs.1,3,4

Bilateral sciatica had lower sensitivity, higher specificity, and low LRs1,2,3,4

Bladder incontinence, bladder retention, decreased urinary sensation, and frequent urination had varying sensitivities and specificities and low LRs.1,2,3,4

Signs (Table 4)

Clinical Guidelines

None found.

Illustrative Case

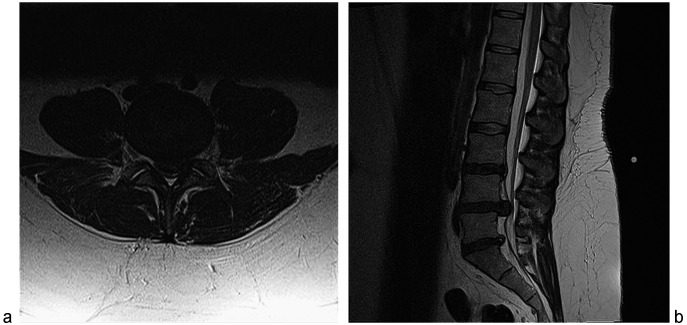

A 37-year-old woman had acute onset of low back pain while lifting at work. During 4 days she experienced pain down her legs, bilateral foot weakness, and perineal numbness. She could no longer sense when her bladder was full and began to wear a diaper. On presentation, strength testing revealed plantar flexion, dorsiflexion, and extensor hallicus longus 0/5 on the right, dorsiflexion and hallucis longus (EHL) 4/5 and plantar flexion 5/5 on the left. She had saddle anesthesia, diminished rectal tone, and more than1000 cc of retained urine upon placing a urinary catheter.

Emergent MRI revealed a massive L4–5 disc herniation causing cauda equina compression (Fig. 2). Despite the delay in referral, she was taken urgently to the operating room for laminectomy and disc excision. She made a full-motor recovery over 2 years but she still has sacral numbness and manually expresses her bladder, although she no longer needed a catheter.

Fig. 2 .

a Axial (left); b sagittal (right). T2 magnetic resonance imaging reveals a massive disc extrusion from the L4–5 level associated with signs and symptoms of cauda equina syndrome.

Discussion

Limitations

Small number of poor studies available (three studies are level IV; one level III).

No indication in any study whether the reference test (MRI) was interpreted in a manner that was blind to the results of the patient history and physical examination.

None of the studies provided sufficient details for replication of both the tests and MRI.

None of the symptoms or signs reported had a likelihood ratio with a magnitude that would suggest ruling in or out CES given the pretest probability of disease.

The literature did not define objective, reliable clinical criteria for the diagnosis of CES.

There are insufficient data in the literature to determine the relationship between signs and symptoms of CES and the timing or severity (ie, complete vs incomplete) of the disease.

While MRI is considered the standard in the diagnosis of CES, the literature reveals a lack of an objective, reliable system of classifying MRI findings. Furthermore, the subjective MRI findings reported in the literature may not be specific to CES.

Insufficient data is present in the literature to identify signs or symptoms that correlated with either negative or positive MRI studies.

Prospective studies evaluating larger cohorts of patients are needed to more definitively determine whether any individual or combination of signs and/or symptoms is associated with CES.

Prospective studies should comprise objective, reliable definitions for CES, including timing and severity of disease, as well as a reliable classification of MRI findings.

Evidence Summary

Editorial Perspective

The subject of cauda equina syndrome (CES) continues to provide ample controversy to all involved in care of spine patients, scientific study, and education. This includes the responses of our reviewers who were split about the best way to approach the subject and then interpret the available literature and what conclusions to draw from the findings. All agree on the following:

CES is a description of a neural deficit best to be avoided in the first place as it describes an ongoing neurological deficit.

CES can be defined as the sudden loss of function of the lumbar and lumbosacral plexus below the conus medullaris due to a number of conditions, such as massive disc herniation, tumor, trauma, and by other forms of neural canal compromise.

The traditional findings of acute loss of bowel and bladder control function, sexual dysfunction, lower extremity weakness, and numbness in the perianal region and lower extremities describe an active process of neurological damage underway for which recovery is unpredictable. Recognition of an immanent CES is clearly preferable to waiting for actual manifestations of CES to occur.

CES remains a major challenge regarding best pathway to timely diagnosis due to a plethora of presentations and large number of confounding factors.

Lumbar MRI remains the preferred diagnostic modality to identify neural space compromise.

In the era of attempting to develop pathways for use of lumbar neural imaging for patients with low back pain based on their clinical presentations, the possibility of missing an evolving CES remains a real challenge. A review of the physical examination findings reported in this systematic review by Fairbanks et al clearly show the main constant of physical findings with patients who ended up experiencing CES was ‘low back pain’. A smaller number of patients presented with bilateral leg pain. All other physical examination findings pretty much described an ongoing evolving CES—the condition all agreed that should be avoided in the first place. The authors clearly found that there was a dearth of reliable patient complaints or physical examination findings in the literature to use as a ‘red flag’ in the development of diagnostic pathways for low back pain. There also appears to be poor correlation of the amount of canal compromise and the evolution as well as severity of neurological deficits.

In conclusion, we can all agree on some points:

CES as a worst-case scenario for a number of conditions, such as disc herniation, clearly begs for further prospective investigation with quality-data collection and analysis.

The neurophysiological basis of CES would benefit from further basic science study.

Low back pain continues to present a major challenge to simplified diagnostic and care pathways due to its highly nonspecific nature.

EBSJ thanks Fairbank and colleagues for tackling this controversial subject and providing a welcome foundation for further investigation.

Footnotes

This systematic review was funded by AOSpine.

References

- 1.Balasubramanian K, Kalsi P, Greenough C G. et al. Reliability of clinical assessment in diagnosing cauda equina syndrome. Br J Neurosurg. 2010;24(4):383–386. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2010.505987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell D A, Collie D, Statham P F. Cauda equina syndrome: what is the correlation between clinical assessment and MRI scanning? Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21(2):201–203. doi: 10.1080/02688690701317144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domen P M, Hofman P A, Santbrink H van. et al. Predictive value of clinical characteristics in patients with suspected cauda equina syndrome. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(3):416–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rooney A, Statham P F, Stone J. Cauda equina syndrome with normal MR imaging. J Neurol. 2009;256(5):721–725. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5003-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]