Abstract

Background

Clinical decision rules have been developed and validated for the evaluation of patients presenting with suspected pulmonary embolism (PE) to the emergency department (ED).

Objectives

To assess the percentage of computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CT-PA) which could have been avoided by use of the Wells score coupled with D-dimer testing (Wells/D-dimer) or Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC) in ED patients with suspected PE.

Methods

The authors conducted a prospective cohort study of adult ED patients undergoing CT-PA for suspected PE. Wells score and PERC were calculated. A research blood sample was obtained for D-dimer testing for subjects who did not undergo testing as part of their ED evaluation. The primary outcome was PE by CT-PA or 90-day follow-up. Secondary outcomes were ED length of stay (LOS) and CT-PA time as defined by time from order to initial radiologist interpretation.

Results

Of 152 suspected PE subjects available for analysis (mean age 46.3±15.6 years, 74% female, 59% black or African American, 11.8% diagnosed with PE), 14 (9.2%) met PERC, none of whom were diagnosed with PE. A low-risk Wells score (≤4) was assigned to 110 (72%) subjects, of whom only 38 (35%) underwent clinical D-dimer testing (elevated in 33/38). Of the 72 subjects with low-risk Wells scores who did not have D-dimers performed in the ED, archived research samples were negative in 16 (22%). All 21 subjects with low-risk Wells scores and negative D-dimers were PE-negative. CT-PA time (median 160 minutes) accounted for more than half of total ED LOS (median 295 minutes).

Conclusions

In total, 9.2% and 13.8% of CT-PA could have been avoided by use of PERC and Wells/D-dimer, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a common and potentially lethal disease. Emergency physicians must assess patients with nonspecific symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, or palpitations, and decide whether testing for PE is warranted. Algorithms incorporating clinical prediction rules and/or D-dimer testing have been developed to guide the evaluation of patients presenting with suspected PE. Two such algorithms, the Wells score coupled with D-dimer testing (Wells/D-dimer), and the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC), have demonstrated high negative predictive value (NPV) in large prospective emergency department (ED) studies.1,2 With the dichotomized Wells score, patients with scores ≤ 4 are classified as low-risk and are recommended to undergo D-dimer testing.3 A normal D-dimer suggests no further testing for PE is indicated, while an elevated D-dimer warrants further evaluation with imaging. Patients deemed to be low probability for PE by clinician gestalt who do not meet any of the PERC are low-risk, and require no further testing for PE.

Implementation of these algorithms in clinical practice is inconsistent.4 As a result, low-risk patients may be subjected to unnecessary imaging leading to increased ED length of stay (LOS), preventable health care expenditures, and in the case of contrast-enhanced computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CT-PA), avoidable health risks of radiation exposure and contrast-related complications.

The purpose of our study was to assess the proportion of CT-PA that could have been avoided by use of Wells/D-dimer or PERC in patients presenting with suspected PE to a large, urban, academic ED.

METHODS

Study Design

We performed a prospective cohort study of patients undergoing CT-PA for suspected PE. The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Study Setting and Population

This study was conducted from December 2009 to May 2010 at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, an urban, academic ED with a yearly ED census of approximately 62,000 patients during the study period.

Trained research assistants, present in the ED from 7AM to midnight 7 days a week, identified and enrolled a convenience sample of patients aged 18 years or older who underwent CT-PA for suspected PE as part of their ED evaluations. We excluded patients with diagnoses of acute PE or deep vein thrombosis (DVT) within four weeks of presentation to the ED; patients who did not provide contact home, cell, or work phone numbers for the 90-day follow-up; and patients unable to provide informed consent.

Study Protocol

Research assistants used standardized data collection forms to record patient contact information, demographics (age, sex, race, and ethnicity), triage vital signs, CT-PA results, and final disposition. ED LOS was defined as the time between room placement in the treatment area and disposition time (time of bed request order for admitted subjects or time of ED discharge for discharged subjects). CT-PA time was defined as time between CT-PA order placement and time of initial radiology interpretation. All times were determined by electronic time stamp from the electronic medical record (EMR). CT-PA was performed using a 64-slice multidetector CT scanner. All CT-PA results were verified by one of the authors using the EMR. CT-PA interpretation was provided by sub-specialty certified chest radiologists Monday through Friday between 8am and 5pm, and by resident or fellow physicians during off-hours, with on-call chest radiologists available for questions. Results of D-dimer assays performed as part of the ED evaluation or as an outpatient in the health system within 24 hours of ED presentation were also recorded.

Treating physicians recorded patients’ clinical information, including features of the history and physical examination needed to calculate the Wells score and evaluate the PERC. The data collection sheets were completed before the results of CT-PA were known. The treating physicians determined all evaluation and management decisions independent of the study or study investigators.

D-dimer Testing

A whole blood sample was drawn from each subject into an evacuated tube buffered with 3.2% sodium citrate (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at the time of enrollment. Platelet-poor plasma was prepared and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis. For those subjects not receiving D-dimer testing as part of their clinical evaluations in the ED, D-dimers were performed on the archived plasma at a later date. All D-dimer tests were performed using the same high-resolution assay (Vidas D-Dimer Exclusion, bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) in the same clinical laboratory. In accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, a result >0.5 µg/ml was considered positive. Treating physicians were unaware of the purpose of the research blood sample, and did not have access to the D-dimer result obtained from the research sample.

Clinical Follow-up

Patients with CT-PAs negative for PE were contacted by telephone 90 days after enrollment to assess whether they had been diagnosed with PE since their initial ED visits. If a patient could not be contacted, the health system EMR was queried to determine if that patient had been given a new diagnosis of PE during the 90-day follow-up period. In addition, the EMR and the social security death index were checked 6 months after the index visit to determine if a patient was deceased at 90-day follow-up and, when possible, a cause of death was obtained via the medical record.

The Wells score was calculated and the PERC criteria were evaluated for each patient. The primary outcome was PE. A patient was considered to have met the primary outcome if he or she had a positive CT-PA at the time of enrollment, or had a new diagnosis of PE at the 90-day follow-up. Secondary outcomes included ED LOS and CT-PA time.

Data Analysis

Continuous variables are presented with means and standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed results or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for skewed distributions. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages. The sensitivity, specificity, NPV, positive predictive value (PPV), negative likelihood ratio, and positive likelihood ratio, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), were calculated for the Wells/D-dimer and PERC. For all analyses, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant with no adjustment for multiple comparisons. To determine differences between PE-negative and PE-positive patients regarding individual Wells criteria, Fisher’s exact test was used. Analyses were performed using StatXact, Version 9.0 (Cytel Software Corporation, Cambridge, MA).

RESULTS

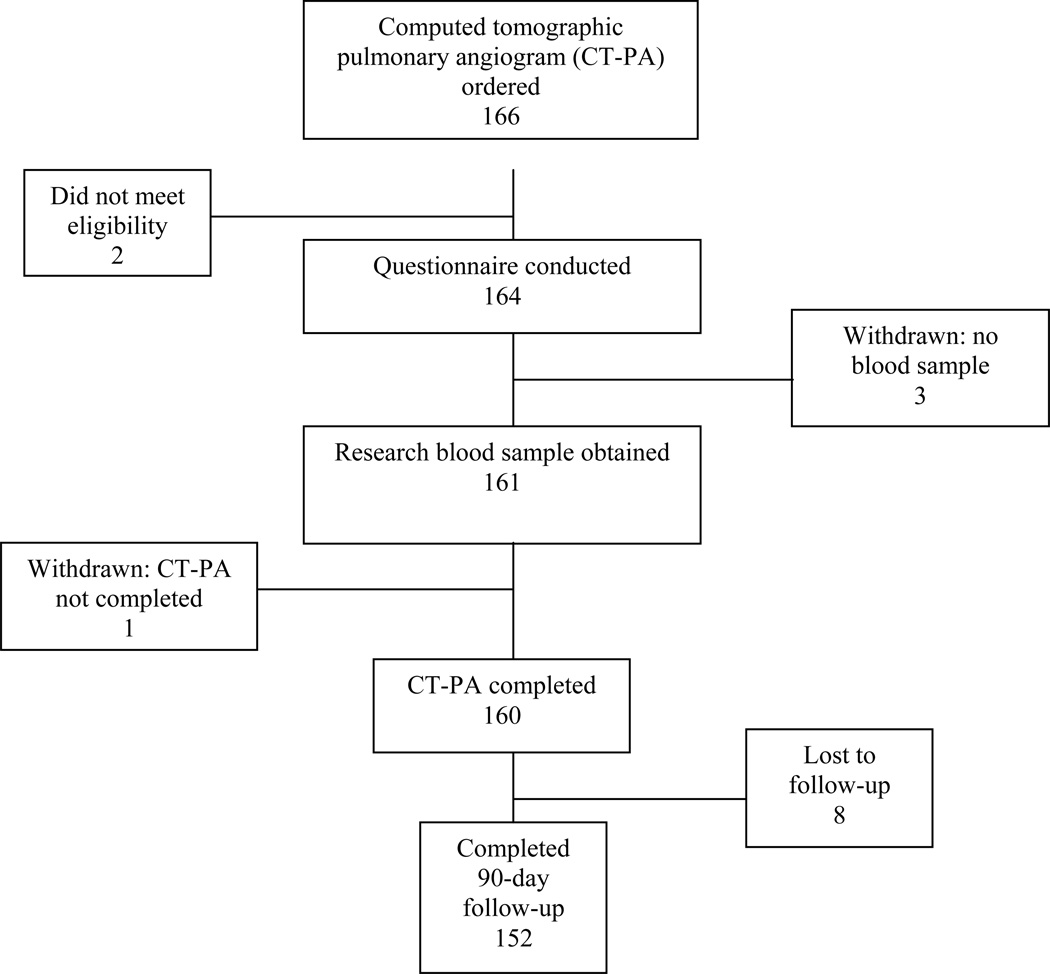

During the study period, 166 patients were enrolled. Two patients were found not to meet eligibility criteria (one had acute DVT in the prior four weeks, one met all eligibility criteria but had an uninterpretable CT-PA and was treated presumptively for PE), three patients had no blood sample collected, one patient had no CT-PA performed, and eight patients were lost to follow-up, leaving 152 patients for analysis (Figure 1). Of the 152 patients, 11 (7.2%) received their follow-up via the EMR, and four (2.6%) via the social security death index. The remainder were contacted by telephone at 90 days.

Figure 1.

Study protocol

Patient characteristics, including demographics, pertinent past medical history, thrombotic risk factors, and presenting signs and symptoms, are listed in Table 1. The patients in the study were predominantly middle aged and female. A number of patients had risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE), including a history of prior DVT or PE, active malignancy, recent surgery or trauma, immobilization, or exogenous estrogen use. The most common presenting signs and symptoms were shortness of breath (77%), chest pain (74.3%), and lower extremity pain or swelling (44.1%). Of the 152 patients, 18 (11.8%) were PE-positive, all of whom were diagnosed by CT-PA on the initial ED visit. No additional PE-positive patients were identified on 90-day follow-up.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Suspected PE n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 152 |

| Demographics | |

| Age (mean ±SD) years | 46.3 ± 15.6 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 40 (26.3) |

| Female | 112 (73.7) |

| Race | |

| Black or African American | 90 (59.2) |

| White | 57 (37.5) |

| Asian or Asian Islander | 2 (1.3) |

| North American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (0.6) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6) |

| Medical history and thromobotic risk factors | |

| Previous pulmonary embolism | 29 (19.1) |

| Previous deep vein thrombosis | 23 (15.1) |

| Active cancer | 31 (20.4) |

| Coronary artery disease | 8 (5.3) |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | 10 (6.6) |

| Pregnant | 3 (2.0) |

| Surgery or bedrest > 3 days duration within past six weeks | 44 (28.9) |

| Trauma within past 6 weeks | 3 (2.0) |

| Lower extremity immobilization (cast, brace, boot) within past six weeks | 9 (5.9) |

| On anticoagulation | 22 (14.5) |

| Exogenous hormone therapy | 12 (7.9) |

| Signs and symptoms | |

| Shortness of breath | 117 (77.0) |

| Chest pain | 113 (74.3) |

| Hemoptysis | 9 (5.9) |

| Lower extremity pain or swelling | 67 (44.1) |

| Localized tenderness along deep venous system | 9 (5.9) |

SD = standard deviation

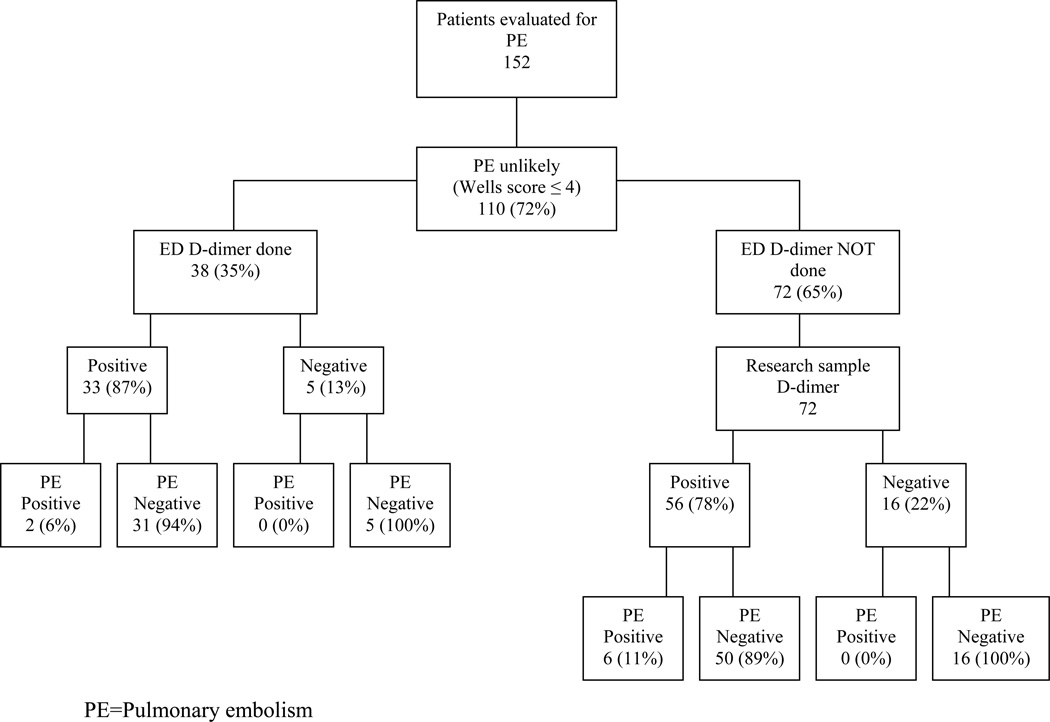

The PERC are listed in Table 2 for the study population. Fourteen (9.2%) patients met all eight PERC, all of whom were PE-negative. Wells score characteristics of PE-positive and PE-negative patients are shown in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups. Of the 152 patients, 110 (72%) had Wells scores ≤ 4 and were classified as “PE Unlikely/Low Risk.” D-dimer testing was performed in the ED in 38 (35%) of these patients and was positive in 33 (Figure 2). Seventy-two (65%) patients with low-risk Wells scores did not have D-dimer testing as part of their ED evaluations. D-dimer studies performed on archived research samples were negative in 16 (22%) of these patients. All 21 subjects with low-risk Wells scores and negative D-dimers were PE-negative (Figure 2). Operating characteristics of PERC and Wells/D-dimer are summarized in Table 4. Both showed NPVs of 100%. Median ED LOS was 295 minutes (IQR 213 to 405.25 min). Median CT-PA time was 160 minutes (IQR 113 to 224 min).

Table 2.

Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC)1 (Total N=152)

| Criteria | Answer of “no” to PERC criterion n (%) |

Patients who met specific criterion who were PE-positive n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Is the patient older than 49 years of age? | 84 (55.3) | 6 (7.1) |

| Is the pulse rate above 99 beats/min? | 100 (65.8) | 8 (8.0) |

| Is the pulse oximetry reading <95% while patient breathes room air? | 131(86.2) | 14 (10.7) |

| Is there a present history of hemoptysis? | 143 (94.1) | 17 (11.9) |

| Is the patient taking exogenous estrogen? | 130 (85.5) | 15 (11.5) |

| Does the patient have a prior diagnosis of venous thromboembolism? | 114 (75) | 14 (12.3) |

| Has the patient had recent surgery or trauma? (requiring endotracheal intubation or hospitalization in the previous 4 weeks) | 123 (80.9) | 11 (8.9) |

| Does the patient have unilateral leg swelling? (visual observation of asymmetry of the calves) | 113 (74.3) | 12 (10.6) |

If the answer is NO to all of these questions, the patient is considered to have met PERC.

Table 3.

Wells Criteria2 and distribution of characteristics (Total N=152)

| Wells Criteria | PE-negative patients (n = 134) |

PE-positive patients (n = 18) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected DVT | 3 (2.2) | 2 (11.1) | 0.107 |

| An alternative diagnosis is less likely than PE | 41 (30.6) | 8 (44.4) | 0.285 |

| Heart rate >100 beats/minute | 40 (29.9) | 9 (50) | 0.108 |

| Immobilization or surgery in the previous 4 weeks | 36 (26.9) | 8 (44.4) | 0.165 |

| Previous DVT/PE | 35 (26.1) | 4 (22.2) | 1.0 |

| Hemoptysis | 8 (6.0) | 1 (5.6) | 1.0 |

| Malignancy (on treatment, treated in the last 6 months, or palliative) | 28 (20.9) | 3 (16.7) | 1.0 |

Data reported as n (%)

DVT = deep vein thrombosis; PE = pulmonary embolism

Figure 2.

Evaluation by D-dimer and outcomes of patients with low-risk Wells score

Table 4.

Operating Characteristics of Algorithms

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | +LR | −LR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERC | 1.00 (0.78–1.00) | 0.10 (0.06–0.17) | 0.13 (0.08–0.20) | 1.00 (0.73–1.00) | 1.12 (1.05–1.18) | 0 |

| Wells/D-dimer | 1.00 (0.78–1.00) | 0.16 (0.10–0.23) | 0.14 (0.09–0.21) | 1.00 (0.81–1.00) | 1.19 (1.10–1.28) | 0 |

PERC = Pulmonary embolism rule out criteria; PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value; +LR = positive likelihood ratio; −LR = negative likelihood ratio

95% Confidence Intervals are shown in parentheses

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to assess the percentage of CT-PA that could have been avoided by use of validated algorithms for the evaluation of patients presenting to the ED with suspected PE. We found that use of PERC or Wells/D-dimer would have safely reduced the number of CT-PA performed by 9.2% and 13.8%, respectively.

Fourteen (9.2%) of the subjects in our study population met PERC and all were PE-negative. These findings are similar to those of prior prospective evaluations of PERC demonstrating high sensitivities. A multicenter study of over 8,000 patients with a 6.9% prevalence of VTE demonstrated PERC to have a sensitivity of 94.7% in low-risk patients.1 A smaller study of 120 ED patients with suspected PE and a 12% prevalence of PE demonstrated a sensitivity of 100%.5 Use of the PERC is recommended in patients with a low pretest probability for suspected PE by clinical gestalt. Not all patients who meet PERC are considered low-risk by clinical gestalt, and the rule’s applicability to this patient group is unknown. As all patients underwent imaging in our study, it may be that gestalt assessment was not considered to be low-risk by the treating physician.

When applying the Wells score to our study population, 72% of patients were classified as “PE Unlikely/Low Risk” based on scores ≤ 4. Per the Wells score algorithm, these patients should have undergone D-dimer testing before receiving CT-PA. Of the 110 low-risk patients by Wells score, only 35% underwent D-dimer testing in the ED. A possible explanation for clinicians’ reluctance to order a D-dimer may be the high frequency of false-positive results. Of the 110 low-risk patients in our study, 81% had elevated D-dimer results, of whom only eight of 89 (9.0%) met the primary outcome of PE. Nevertheless, 21 of the 110 low-risk patients had normal D-dimers, and could have avoided imaging; none of these patients met the primary outcome of PE. Our results are similar to those of previous prospective studies evaluating the dichotomized Wells score. In a multicenter study of 3,306 patients, 1,057 were classified as “PE unlikely” and had negative D-dimer results, with five patients (0.5%) receiving diagnoses of VTE on three-month follow-up, with no deaths.6

A criticism of the Wells score is that it is not entirely objective, as the algorithm contains the subjective variable “an alternative diagnosis is less likely than PE.” This may allow for clinician judgment to enter into the decision rule, placing the patient into a higher or lower risk category given the three-point value to this variable. In addition, other variables may be more predictive for PE than those that are currently included in validated algorithms. A recent multi-center study of almost 8,000 patients showed that in symptomatic patients being considered for possible PE, non-cancer-related thrombophilia, pleuritic chest pain, and family history of VTE increased the probability of PE or deep vein thrombosis.7 None of these variables are part of the Wells score or PERC.

Overuse of CT-PA is likely to have important economic and medical consequences. As a secondary outcome, we evaluated ED LOS and CT-PA time. We found that the median CT-PA time (160 minutes) comprised a substantial fraction of overall median ED LOS (295 minutes). However, whether avoidance of CT-PA in low-risk patients reduces LOS cannot be determined from our study, due to the absence of an appropriate comparison group. Time waiting for potentially unnecessary imaging may contribute to crowding, which has been associated with poor care in the ED, including delays in medications and increased mortality rates.8–11 CT-PA also contributes to increased health care expenditures.12

The use of CT has increased dramatically in the United States over the past two decades, and approximately 14% of all emergency patients now undergo CT scans during their ED visits.13 This not only increases resource use, financial costs, and LOS, but also increases patient exposure to contrast media and radiation exposure risks. The median effective dose for chest CT for suspected pulmonary embolism is 10 mSv.14 An increased risk of cancer has been demonstrated among long-term survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs, who received exposures of 10 to 100 mSv.15–17 Contrast-induced nephropathy is another recognized adverse consequence from contrast-enhanced imaging, and leads to increased morbidity and mortality. A recent study of ED patients receiving intravenous contrast for CT demonstrated an 11% rate of contrast-induced nephropathy.18 Other unintended consequences of contrast-enhanced imaging, such as significant allergic reactions and extravasation of contrast, are rare but clinically important.

Validated clinical decision rules have the potential to reduce unnecessary CT-PA and its associated adverse consequences. However, such rules were underutilized in our study and in other settings.4 One potential barrier to use of these rules is that physicians may feel that clinical gestalt is similar or superior. Several studies have compared clinical gestalt assessment to the Wells score and have found comparable results in assessing pretest probability.19–21 Moreover, some clinicians may err on the side of ordering unnecessary CT-PA in low-risk patients for fear of litigation. Runyon et al. demonstrated that only half of physicians who are familiar with commonly used clinical decision rules use them in more than half of appropriate patients. In addition, the physicians’ spontaneous recall of the rules was low to moderate.4

More work is needed to understand the barriers to implementation of decision rules for PE in the ED and to formulate strategies for overcoming these barriers. Future investigations are needed to evaluate the ability of electronic clinical decision support to aid in the assessment of pretest probability. Larger studies showing a significant benefit of decision rules over gestalt for suspected PE are also likely needed, to persuade physicians of the worth of these diagnostic tools.

LIMITATIONS

Our study population was confined to ED patients undergoing CT-PA for the evaluation of suspected PE, and did not include patients evaluated for PE who did not have imaging, or underwent an alternative imaging modality such as ventilation/perfusion scanning. Consequently, our study does not provide an estimate of the overall frequency of use of decision rules in the management of patients with suspected PE. In addition, treating clinicians were not questioned as to their clinical gestalt or pretest probability for PE, nor to their reasoning for whether or not to use a clinical decision rule. However, since a significant percentage of the patients undergoing CT-PA in the study were classified as “PE unlikely/low risk,” we feel that there is room for improvement.

The study was conducted at one ED, so the results may not be generalizable to other EDs in other settings. In addition, the sample size of the study population was small. While we examined the use of two common clinical decision rules, Wells score and PERC, there are other commonly used scores such as the Geneva score and Pisa model, which were not evaluated. The integrity of the blood sample is maintained despite storage. Nine patients each received an ED D-dimer and a research D-dimer. Results were not significantly different by paired t-test (p = 0.16). There was also perfect concordance with respect to classification. Eight subjects with positive ED D-dimers also had positive research D-dimers. The remaining subject tested negative by both ED and research D-dimer assay.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that a clinically meaningful percentage of computed tomography pulmonary angiography in patients presenting to the ED with suspected pulmonary embolism could have been potentially avoided through use of validated clinical decision rules.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by grant K12HL087064 of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (A.Cuker).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest for further funding disclosures to report.

Presentations: Society for Academic Emergency Medicine annual meeting, Boston MA, June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kline JA, Courtney DM, Kabrhel C, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(5):772–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(2):98–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83(3):416–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Runyon MS, Richman PB, Kline JA. Emergency medicine practitioner knowledge and use of decision rules for the evaluation of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: variations by practice setting and training level. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(1):53–57. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf SJ, McCubbin TR, Nordenholz KE, Naviaux NW, Haukoos JS. Assessment of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria rule for evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(2):181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Belle A, Buller HR, Huisman MV, et al. Effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and computed tomography. JAMA. 2006;295(2):172–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtney DM, Kline JA, Kabrhel C, et al. Clinical features from the history and physical examination that predict the presence or absence of pulmonary embolism in symptomatic emergency department patients: results of a prospective, multicenter study. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(4):307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills AM, Baumann BM, Chen EH, et al. The impact of crowding on time until abdominal CT interpretation in emergency department patients with acute abdominal pain. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(1):75–81. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.01.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills AM, Shofer FS, Chen EH, Hollander JE, Pines JM. The association between emergency department crowding and analgesia administration in acute abdominal pain patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:603–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pines JM, Hollander JE. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust. 2006;184(5):213–216. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States Government Accountability Office. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office; 2008. Medicare part B imaging services: rapid spending growth and shift to physician offices indicate need for CMS to consider additional management practices; pp. 1–55. GAO-08–452. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kocher KE, Meurer WJ, Fazel R, Scott PA, Krumholz HM, Nallamothu BK. National trends in use of computed tomography in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(5):452–462. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2078–2086. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenner DJ, Doll R, Goodhead DT, et al. Cancer risks attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: assessing what we really know. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(24):13761–13766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235592100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierce DA, Preston DL. Radiation-related cancer risks at low doses among atomic bomb survivors. Radiat Res. 2000;154(2):178–186. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)154[0178:rrcral]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preston DL, Ron E, Tokuoka S, et al. Solid cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors: 1958–1998. Radiat Res. 2007;168(1):1–64. doi: 10.1667/RR0763.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell AM, Jones AE, Tumlin JA, Kline JA. Immediate complications of intravenous contrast for computed tomography imaging in the outpatient setting are rare. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:1005–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabrhel C, Mark Courtney D, Camargo CA, Jr, et al. Potential impact of adjusting the threshold of the quantitative D-dimer based on pretest probability of acute pulmonary embolism. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Runyon MS, Webb WB, Jones AE, Kline JA. Comparison of the unstructured clinician estimate of pretest probability for pulmonary embolism to the Canadian score and the Charlotte rule: a prospective observational study. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:587–593. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanson BJ, Lijmer JG, Mac Gillavry MR, Turkstra F, Prins MH, Buller HR. Comparison of a clinical probability estimate and two clinical models in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. ANTELOPE-Study Group. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83(2):199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]