Abstract

The modes of transmission model has been widely used to help decision-makers target measures for preventing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The model estimates the number of new HIV infections that will be acquired over the ensuing year by individuals in identified risk groups in a given population using data on the size of the groups, the aggregate risk behaviour in each group, the current prevalence of HIV infection among the sexual or injecting drug partners of individuals in each group, and the probability of HIV transmission associated with different risk behaviours. The strength of the model is its simplicity, which enables data from a variety of sources to be synthesized, resulting in better characterization of HIV epidemics in some settings. However, concerns have been raised about the assumptions underlying the model structure, about limitations in the data available for deriving input parameters and about interpretation and communication of the model results. The aim of this review was to improve the use of the model by reassessing its paradigm, structure and data requirements. We identified key questions to be asked when conducting an analysis and when interpreting the model results and make recommendations for strengthening the model’s application in the future.

Résumé

Le modèle de modes de transmission a été largement utilisé pour aider les décideurs à cibler les mesures empêchant l'infection par le virus d'immunodéficience humaine (VIH). Le modèle estime le nombre de nouvelles infections par le VIH au cours de l'année suivante, contractées par des individus appartenant aux groupes à risque identifiés d’une population donnée, en utilisant des données sur la taille des groupes, le comportement à risque global de chaque groupe, la prévalence actuelle de l'infection par le VIH entre partenaires sexuels ou d'injection de drogues de chaque groupe, et la probabilité de transmission du VIH associée aux divers comportements à risque. La force du modèle réside dans sa simplicité, permettant de synthétiser des données provenant d'une variété de sources, ce qui donne une meilleure caractérisation de l'épidémie du VIH dans certains contextes. Toutefois, des problèmes ont été relevés concernant les hypothèses qui sous-tendent la structure du modèle, les limites des données disponibles pour obtenir les paramètres d'entrée, ainsi que l'interprétation et la communication des résultats du modèle. L’objectif de la présente étude était d'améliorer l'utilisation du modèle en réévaluant son paradigme, sa structure et ses exigences en termes de données. Nous avons identifié les principales questions à poser lors de l'analyse et de l'interprétation des résultats du modèle, et nous faisons des recommandations visant à renforcer l'application du modèle à l'avenir.

Resumen

El modelo de los modos de transmisión se ha empleado de manera generalizada para ayudar a los responsables de la toma de decisiones a dirigir las medidas para la prevención de la infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH). El modelo calcula el número de infecciones por VIH nuevas adquiridas durante el año subsiguiente por individuos en grupos de riesgo identificados en una población dada empleando datos acerca del tamaño de los grupos, el comportamiento de riesgo conjunto en cada grupo, la prevalencia actual de la infección por VIH entre las parejas sexuales o personas que comparten jeringuillas para el consumo de drogas de los individuos de cada grupo y la probabilidad de trasmitir el VIH asociada a los diferentes comportamientos de riesgo. El punto fuerte del modelo es su sencillez, que permite sintetizar datos de fuentes variadas, de lo que resulta una caracterización más exacta de la epidemia del VIH en algunos entornos. No obstante, han surgido dudas acerca de las suposiciones que subyacen a la estructura del modelo, las limitaciones de los datos disponibles para derivar de ellos parámetros de entrada y la interpretación y comunicación de los resultados del modelo. El objeto de este examen fue el de mejorar el uso del modelo volviendo a examinar su paradigma, su estructura y los requisitos de los datos. Identificamos los puntos clave que deben cuestionarse durante la realización de un análisis y la interpretación de los resultados del modelo y formulamos recomendaciones para consolidar la aplicación del modelo en el futuro.

ملخص

تم استخدام أنماط نموذج سريان العدوى على نطاق واسع بغية مساعدة صناع القرار في استهداف التدابير الرامية لتوقي عدوى فيروس العوز المناعي البشري (HIV). ويقدر النموذج عدد الأمراض الجديدة لفيروس العوز المناعي البشري التي سيكتسبها الأفراد على مدار العام التالي في الفئات المعرضة للخطر المحددة في سكان معينين باستخدام البيانات المعنية بحجم الفئات، والسلوك المنطوي على المخاطر المتراكمة في كل فئة، ومعدل الانتشار الحالي لعدوى فيروس العوز المناعي البشري بين القرناء في العلاقة الجنسية أو من يتعاطون المخدرات عن طريق الحقن من الأفراد في كل فئة، واحتمالية سريان عدوى فيروس العوز المناعي البشري المرتبطة بالسلوكيات المختلفة المنطوية على مخاطر. وتتمثل قوة النموذج في بساطته التي تتيح استخلاص البيانات من مصادر متعددة، مما يسفر عن تحديد سمات أوبئة فيروس العوز المناعي البشري في بعض المواقع على نحو أفضل. ومع ذلك، أثير قلق بشأن الافتراضات التي تتضمنها بنية النموذج، وبشأن القيود في البيانات المتاحة لاشتقاق بارامترات المدخلات، وبشأن تفسير نتائج النموذج والإبلاغ عنه. وكان هدف هذا الاستعراض تحسين استخدام النموذج من خلال إعادة تقييم هيكله وبنيته ومتطلبات بياناته. وقمنا بتحديد أسئلة رئيسية من المقرر طرحها عند إجراء تحليل وعند تفسير نتائج النموذج وإصدار التوصيات من أجل تعزيز تطبيق النموذج في المستقبل.

摘要

传播模式模型已被广泛用来帮助决策者确定防止艾滋病毒(HIV)感染的措施。该模型使用群体规模、每个群体中的总计风险行为、每个群体中个人的性或注射毒品伙伴之间的HIV感染的当前流行度和不同风险行为相关的HIV传播可能性的数据来估计在给定人口中识别出的高危人群中的个体在次年的新发HIV感染数。模型的优点在于它的简单性,这样就能将各种来源的数据综合,在某些环境中得到对HIV流行的更好表征。然而,人们对支持模型结构的假设、获取输入参数的可用数据的限制和模型结果的解释和沟通提出疑虑。本综述的目的是通过重新评估其范例、结构和数据的要求来改善模型的使用情况。我们确定了进行分析和解释模型的结果时要问的关键问题,并提出了加强模型未来应用的建议。

Резюме

Формы модели передачи широко используются для помощи ответственным органам в планировании мер по предотвращению заражения вирусом иммунодефицита человека (ВИЧ). Модель оценивает число новых ВИЧ-инфекций, которые будут приобретены в течение последующего года лицами в установленных группах риска в данной популяции, с помощью данных о численности групп, совокупному рискованному поведению в каждой группе, текущей распространенности ВИЧ-инфекции среди сексуальных партнеров или употребляющих инъекционные наркотики в каждой группе и вероятности передачи ВИЧ-инфекции, связанной с различным рискованным поведением. Преимуществом данной модели является ее простота, которая позволяет объединить данные, полученные из различных источников, что дает лучшее представление об эпидемиях ВИЧ в определенных условиях. Тем не менее, возникли вопросы в отношении допущений, лежащих в основе структуры модели, ограниченности доступных данных для формирования входных параметров, а также интерпретации и представления результатов моделирования. Целью данного обзора являлось улучшение использования модели посредством повторной оценки ее парадигм, структуры и требований к данным. Нами были определены ключевые вопросы, которые необходимо ставить при проведении анализа и интерпретации результатов модели, а также предложены рекомендации по совершенствованию применения модели в будущем.

Introduction

In the current global financial climate, it is more important than ever that effective resource allocation for the control of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is based on informed, strategic decision-making. Planning HIV prevention programmes requires up-to-date information on the likely sources of new infections and mathematical modelling provides a framework for understanding epidemic patterns and for highlighting priority areas for prevention. Various models of HIV epidemics, in particular the modes of transmission (MOT) model recommended by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS),1 are used to increase understanding and to assist national planning.2–10

When constructing a model, it is important to include adequate detail to address the questions posed. Superfluous detail reduces the transparency of the model and can make it more difficult to estimate model parameters reliably, whereas excluding important details can lead to erroneous conclusions. The MOT model was developed in 2002 and was designed to focus on identifying who is at risk of infection rather than on the broad categorization of the type of epidemic (i.e. low-level, concentrated, generalized or hyperendemic).11 Its aim was to provide better information for strategic planning of disease prevention.

Unlike models that are region-specific (e.g. the Asian Epidemic Model)12 or country-specific (e.g. the Actuarial Society of South Africa model,13 used primarily in South Africa but also in other countries in southern Africa), the MOT model was designed to be easy to use and can be applied in any epidemic setting. It differs from other approaches, such as the Estimation and Projection Package14 curve-fitting approach embedded within the Spectrum modelling software,15 which estimates and projects HIV prevalence and incidence from surveillance data and does not aim to take mechanisms of infection into account.

Use of the MOT model at the country level was recommended in 2008 as part of a synthesis process supported by UNAIDS and the World Bank Global HIV/AIDS Monitoring and Evaluation Team in southern and eastern Africa,16,17 consistent with the UNAIDS “know your epidemic, know your response” strategy.18 This approach emphasizes the importance of understanding, at the local level, which subpopulations are most at risk of HIV infection and which risk behaviours may facilitate transmission and of using this information to tailor national responses.

When evaluating the performance of a model that is widely used to assist countries in decision-making, it is important to consider the perspective and experience of individuals involved in the modelling process, including those involved in developing and implementing the model, those who rely on the model results for decision-making and the normative agencies that help support the modelling process. In April 2011, the HIV Modelling Consortium (participants are listed in the acknowledgements section) gathered together stakeholders involved in different stages of the modelling process to review both the methods used for estimating sources of HIV infection and the MOT process.19 The impetus for this manuscript originated from discussions at this meeting; one outcome of the meeting was a manuscript that described the strengths and limitations of the MOT process.

Our intention was to strengthen future use of the MOT model by reviewing its principle features in detail and by summarizing feedback from previous applications. Specifically, we aimed to clarify the model paradigm, to review the model structure and data requirements and to propose questions that can be used to guide interpretation of the model results.

Modes of transmission model

The MOT model uses information on the current distribution of prevalent infections in a population and assumptions about patterns of risk behaviour within different risk groups to calculate the expected distribution of new adult HIV infections in the following year in terms of the mode of exposure. The inputs to the model, which are based on a comprehensive review of available epidemiological and behavioural information, are:

the proportion of the adult male and female population that belongs to each of several risk groups, which are precisely defined by each country, including: sex workers and their clients, injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, individuals with multiple heterosexual sex partners in the last year, the spouses of individuals with higher-risk behaviour and individuals in stable heterosexual relationships (i.e. generally married or cohabiting couples with one monogamous heterosexual partner in the last year; these individuals were previously referred to as “low risk”);

the prevalence of HIV infection and of a generic sexually transmitted infection (STI) within each risk group;

the average number of sexual or injecting partners per year and the average number of exposures per partner, taking into account the average level of protective behaviour (e.g. condom use or the use of clean needles), for individuals in each risk group;

the probability of HIV transmission per exposure act in each risk group, taking into account the effect of STIs and the prevalence of male circumcision.

The model estimates the number of new adult HIV infections that will occur over the ensuing year in each risk group from the number of HIV-susceptible individuals, the number of contacts each had with HIV-positive individuals and the probability of HIV transmission associated with each type of contact. Taken together, this provides an estimate of the distribution of new infections in adults according to the population risk structure defined by each country.

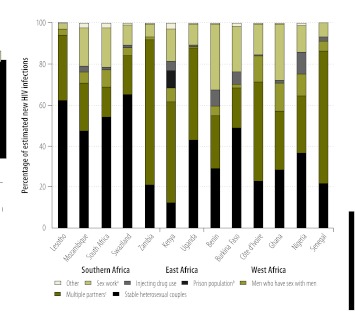

By the end of 2012, over 40 countries with a diverse range of HIV epidemics will have completed or begun an MOT analysis (Table 1, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/11/12-102574). The results of model analyses conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 1) show that the majority of new infections were expected to occur in the general heterosexual population, either in serodiscordant couples or as a result of having multiple sexual partners. Although there is substantial uncertainty, the estimated proportion of new infections that occur in men who have sex with men and in injecting drug users in many countries in this region is larger than acknowledged before the advent of the MOT framework.

Table 1. Countries using the modes of transmission model to estimate the source of new HIV infections, by region, 2005–2013.

| Region and country | Year model analysis completed | Year model analysis started or planned to start |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||

| Angola | 2012–2013 | |

| Benin | 2009 | |

| Burkina Faso | 2009 | |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 2009 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 2012–2013 | |

| Ethiopia | 2012 | |

| Ghana | 2009 | |

| Kenya | 2005 and 2008 | |

| Lesotho | 2008 | |

| Malawi | 2012–2013 | |

| Mozambique | 2008 | |

| Nigeria | 2009 | |

| Rwanda | 2009 | |

| Senegal | 2009 | |

| South Africa | 2010 | |

| Swaziland | 2008 | |

| Uganda | 2008 | |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 2012 | |

| Zambia | 2008 | |

| Zimbabwe | 2011 | |

| Middle East and northern Africa | ||

| Djibouti | 2012 | |

| Islamic Republic of Iran | 2011 | |

| Morocco | 2010 | |

| Tunisia | 2012 | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | ||

| Brazil | 2012 | |

| Costa Rica | 2012 | |

| Dominican Republic | 2009–2010 | |

| El Salvador | 2012 | |

| Guatemala | 2012 | |

| Guyana | 2012 | |

| Jamaica | 2012 | |

| Mexico | 2012 | |

| Nicaragua | 2012 | |

| Panama | 2012 | |

| Peru | 2009 | |

| Eastern Europe and central Asia | ||

| Armenia | 2011 | |

| Belarus | 2012 | |

| Georgia | 2012 | |

| Republic of Moldova | 2011 | |

| Asia and Pacific | ||

| Indonesia | 2011 | |

| Myanmar | 2011 | |

| Nepal | 2011 | |

| Philippines | 2011 | |

| Thailand | 2005 |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Fig. 1.

Sources of new HIV infections estimated by the modes of transmission model in sub-Saharan Africa, 2008–2010

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a Sex work refers to new infections in sex workers, their clients and the regular or stable partners of clients.

b Assessed only in Kenya.

c Multiple partners refers to both individuals who have more than one partner and the regular or stable partners of those with multiple partners.

Benefits

The MOT analysis forms part of a multistage process that typically includes: (i) a comprehensive review and synthesis of epidemiological and behavioural data; (ii) use of the MOT model to estimate the distribution of new infections; (iii) a review of existing or proposed HIV prevention planning and resource allocation for treatment and prevention; (iv) a comparison of resource allocation and the modelled distribution of sources of infection, and (v) a national stakeholder consensus meeting to discuss the model results and formulate key recommendations. This process provides a framework for countries to interpret and evaluate their data, to assess data availability and quality, and to identify gaps in data collection. It can help consolidate knowledge of the current situation, but can also expose gaps in information about specific risk behaviours. In addition, the model results could be used to raise awareness for groups that may not previously have received enough attention, to highlight areas for improvement in prevention and to identify areas for further research. Although the concept of the MOT analysis has gained broad support, important questions have been raised about the simplicity of the model, its use of data and how the results are interpreted.

Limitations

The limitations of the MOT model and its assumptions can be divided into three categories relating to the model structure, the data used in the model and the interpretation of the results.

Model structure

The MOT model is a static model representing risk in a single year. It has a simple structure that does not incorporate many of the complexities of HIV epidemiology. It assumes that the populations in each risk group are mutually exclusive and that the risk of infection is homogenous within each group. This means, for example, that all men who have sex with men are assumed to have the same risk of infection. Moreover, the assumption of homogeneity would not capture details such as the clients of sex workers only visiting a particular type of sex worker or an injecting drug user sharing injecting equipment only within a specific cluster. These factors could influence the model results if there are important differences among those classified as belonging to the same risk group. However, the model offers the flexibility to disaggregate a subpopulation if there is enough evidence of heterogeneity in risk and sufficient data are available to characterize the different subgroups within a subpopulation, but generally suitable data are not available.

In the model, individuals must be assigned to a single risk group and are, consequently, assumed to be at risk of infection from only one source. Those at risk of infection from more than one source are classified according to the behaviour associated with the highest probability of HIV transmission. For example, a sex worker who also injects drugs is classified as an injecting drug user. This assumption implies that eliminating that source of risk will avert infection. An analysis that looked at the effect of modifying the model structure to allow for an individual’s risk of infection from more than one source found that assuming a single source could result in overestimating the potential impact of interventions targeting that source.20 Conversely, the effect of interventions targeting a less risky behaviour could be underestimated if the size of the risk group is underestimated because that behaviour ranks lower in the hierarchy of risk. For example, the model assumes that sex workers who are also injecting drug users and who would be classified as such would not benefit from a successful intervention among sex workers.

The probabilities of HIV transmission for different exposure acts and the parameter used to modify these probabilities when an STI is present are derived from published data, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies.21–23 While these sources represent the best available evidence, they may not capture potential variability of transmission in different geographical settings.23,24 Additionally, it is assumed that there is no variation in transmission probability by stage of HIV infection and the model does not allow temporal patterns of sexual contacts, such as concurrent sexual partnerships, to influence transmission. Previous MOT analyses have not allowed for the effect of antiretroviral therapy on transmission, but this has been incorporated in the latest revision of the model.

In the model, the size of the “low-risk” or “stable heterosexual” subpopulation is sometimes calculated as a residual after the sizes of other groups are entered to ensure the summed size of the groups matches the total population size. This creates a dependency between the sizes of the different risk groups, so that, if the summed size of the high-risk groups is underestimated, the importance of the low-risk group will be overestimated. Thus, poor data quality for a single risk group can result in biased estimates and misinterpretation of the relative importance of the low-risk group.

While the MOT model calculates the cumulative number of incident cases of HIV infection in 1 year, it does not capture secondary HIV transmission arising from onward transmission within that year. Further, the MOT model assumes that the population is closed and defined by country borders and a defined age range. The estimates obtained are for new HIV infections that arise within a country and do not account for exogenous HIV exposures, which may contribute to a considerable fraction of HIV infections in some countries, in the Middle East and northern Africa, for example.25,26 As epidemics mature, the contribution of older adults, outside the age range of 15 to 49 years that is typically used in the MOT model, to new HIV transmissions may increase.27 The model can be adapted to incorporate older age groups if data are available.

Data inputs

The MOT model requires detailed, up-to-date information on the size of risk groups and on the prevalence of HIV infection and of other STIs and precise descriptions of sexual behaviour in each risk group. Often this exceeds the data available, particularly when describing hidden or stigmatized populations, but also when describing the general population in countries where national survey data are not available. Standard survey instruments do not collect specific information on the detailed inputs required by the MOT model and most other models, including the average number of sex acts per partnership, injecting behaviour and the prevalence of HIV and STI in each risk group. It is unlikely that all the information needed to characterize a specific group can be obtained from a single study. Instead, estimates are often based on data from several sources that were collected at different times within a prespecified period, typically 5 years, using different study designs.

The quality of the model results depends on the quality of the input data and the MOT model is highly sensitive to the size of subpopulations28 and to behaviour within risk groups. Although guidelines exist for estimating population size,29 the methods used are often complex and of uncertain precision, particularly for hidden or hard-to-reach populations such as men who have sex with men in Africa.30 Consistently defining the risk of HIV infection is not straightforward in certain populations, for example, women who occasionally sell sex in informal settings but do not self-identify as sex workers. These factors contribute to the use of different estimation methods, producing substantially varying population size estimates which could affect the model results.31

The patterns of risk behaviour ascribed to high-risk groups may be subject to bias in self-reported measures of behaviour. National household surveys, such as the Demographic and Health Survey, are often used as a source for sensitive information on, for example, individuals who engage in casual heterosexual sex or the clients of sex workers. Increasing evidence suggests that higher-risk behaviour may be substantially underreported in these surveys.32–34 Other sources of HIV prevalence and behavioural data for hard-to-reach, hidden or stigmatized populations may not be representative. Such data generally come from surveillance or behavioural studies in capital cities or urban centres (often via convenience samples) and may be difficult to extrapolate to national-level estimates.

Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that the MOT model requires fewer data than many dynamic models, which have the same data limitations, but still aims to capture the mechanisms of infection.

Interpreting and communicating results

The major misunderstanding of the model results comes from a misapprehension of the question addressed by the model analysis. The model calculates the estimated distribution of new infections in 1 year; it does not take into account the number of secondary infections that will result from new infections in a risk group. It is important to distinguish between identifying among whom new infections are predicted to occur in the short term, which the model does, and the types of risk behaviour that sustain the epidemic (i.e. the epidemic drivers).31 For example, although a large proportion of new HIV infections may occur among individuals in serodiscordant, stable, monogamous partnerships, the index HIV-positive partners in these couples may have previously acquired the infection through higher-risk behaviour, such as commercial sex. Currently, both partners would be classified as part of the low-risk population, but the essential driver of HIV transmission between the partners is previous sexual contact within commercial sex networks. This is an important distinction, particularly when the model results are used for planning prevention programmes, which may then underallocate resources for prevention in commercial sex settings. Allocating resources for prevention to match the predicted distribution of new infections identified in the MOT analysis implicitly focuses prevention efforts on reducing the risk of acquisition among susceptible individuals. However, in some cases, it may be more effective or efficient to target prevention efforts towards the individuals who contribute most to onward transmission.31

One difficulty with the communication of the results of the MOT model is that concise pie or bar charts (Fig. 1) do not represent uncertainties in input data, which can be substantial. Users of the MOT model can conduct a simple uncertainty analysis based on specifying plausible ranges for key input variables. Then, a large number of parameter combinations from the specified plausibility bounds are independently and uniformly sampled and outputs are calculated for each combination of parameters. During this process, the prevalence of HIV infection in the total population is maintained by adjusting the size of the low-risk group and the prevalence in that group. While this method gives some notion of how uncertainty in input data could affect the model outputs, it does not take into account systematic bias or correlated errors between model inputs. The results can also vary substantially depending on the plausible ranges specified by the user and the use of plausibility ranges for model parameter values does not take account of the intrinsic uncertainty caused by the simplified model structure. In addition, use of the low-risk group as a “catch-all” for maintaining internal consistency neglects the fact that countries with good surveillance of HIV infection in the general population may have more robust data on the low-risk group than on less surveyed, high-risk groups.

Nevertheless, even simple demonstration of how uncertainties in certain model inputs translate into uncertainties in outputs is helpful. Representation of uncertainty is a strength and an important consideration in decision-making. If recommendations do not change when uncertainty is taken into account, decision-makers can have more confidence in the use of the model results. However, if the implications are more ambiguous, decisions about resource allocation based on the model results should reflect this and priority should be given to improving knowledge about parameters that contribute most to uncertainty. Box 1 lists questions that should be considered when conducting an MOT analysis and interpreting the model results. Responses to these questions can help in forming a cautious, nuanced analysis of the model results that will ultimately strengthen its contribution to decision-making.

Box 1. Questions to ask when conducting a modes of transmission analysis and interpreting the results of the modes of transmission model.

How complete is and what is the quality of the data available for model inputs and model validation?

How robust are data on the size of population subgroups, particularly subgroups that may be stigmatized?

Could the size of key population subgroups at an increased risk of HIV infection be underestimated or overestimated?

Could risk behaviour (e.g. number of sexual partners or sex acts) or protective behaviour (e.g. use of clean needles or condoms) be underestimated or overestimated?

Could the number of new infections in a high-risk group or the low-risk group be underestimated or overestimated as a result of the way the model represents these groups?

Is it possible to have a substantial contribution of new infections from outside the borders of the geographical region or outside the age group under study that are not captured?

Are the model results consistent with other epidemiological information?

Are the uncertainties in model inputs and the limitations of the model structure fully reflected in the communication of the results?

How should estimates of the distribution of new infections in the short term be used?

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

The way forward

Mathematical modelling can be used to inform health policy and focus decision-making on key issues, for example, in the design and allocation of resources for HIV prevention programmes. However, translating model outputs into policy decisions should be done carefully and within the local context. In addition, the results need to be interpreted considering the underlying structure of the model, the sensitivity of outputs to variations in model parameters and the potential deficiencies in data quality or availability. Recently, UNAIDS developed a toolkit to help countries assess the availability, completeness and quality of the epidemiological data before application of the MOT model.

Box 2 contains a list of recommendations for improving the use of the MOT model. Viewing the modelling exercise as a process rather than an endpoint and using it as a tool to identify key data needs and to understand which aspects of the data or the model structure affect results will ensure more constructive use of the model. This will enable those advising policy-makers on the basis of modelling to help distinguish between decisions that can be recommended robustly and decisions on which the model is unable to provide clear guidance. A way to increase confidence in the model findings is to test whether the model can be corroborated with other independent data or epidemiological information.

Box 2. Recommendations for improving the use of the modes of transmission model for estimating the source of new HIV infections.

Synthesize and triangulate available data. Conduct a comprehensive review of all data available on HIV infection, STIs, size estimates for risk groups, and sexual and injecting behaviours before beginning the MOT analysis to identify the best available data for model input parameters. Attempt to build a coherent picture of the epidemiology of HIV infection through synthesis and triangulation of the different data sources available.

Emphasize the use of the MOT model as a process. If no other modelling results or data are available for comparison or if the model is insufficiently informed, use the model as a process rather than a means of deriving hard outcomes. Complete the analysis as a way of evaluating the data available with less emphasis on generating an end result and more focus on understanding gaps in knowledge about the epidemic, behaviour, the different risk groups, the validity and reliability of the data available and the gaps in data collection.

Improve the consideration given to data quality. It is important that the data used are representative. Good quality data are essential for estimates of the size of the risk groups in a population and the prevalence of HIV infection in each group. Biases in population estimates in one group can lead to biased estimates about the contribution of other groups.

Adopt a bottom-up approach. Identify the data available to parameterize the model and identify the questions to be answered before tailoring the model to the local level. Where epidemiological information indicates that there are key distinctions in risks of infection within groups or patterns of mixing between groups, consider representing this in the model, if sufficient data are available.

Validate the model results. Compare the results of the MOT model with epidemiological evidence and with findings from data synthesis and triangulation. Explain any differences. The model results may be compared with surveillance data, survey data, case reports and results from other models, including dynamic transmission models.

Establish minimum conditions for conducting the MOT analysis. Define minimum data requirements and identify the conditions under which it is advisable to carry out an analysis using the MOT model. The analysis is intended to increase understanding of an HIV epidemic but some countries may already have robust surveillance and empirical data and a good understanding. Conversely, too much data may be missing for the analysis to be considered worthwhile.

Strengthen the uncertainty analysis. Allow for correlated errors in input data. Extend the uncertainty analysis to examine, where possible, the influence of key modelling assumptions on, for example, patterns of mixing between groups and heterogeneities in risk within groups. Ensure that uncertainty estimates are reflected in the presentation of results.

Be clear about what the model results mean. The MOT model estimates the distribution of new HIV infections in the short term, which does not necessarily reflect the most important drivers of the epidemic.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MOT, modes of transmission; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

One strength of the MOT model is that it has been designed to acknowledge and evaluate potential sources of infection in a range of settings. In some countries with particularly strong epidemiological surveillance, country-specific models or modified versions of the MOT that expand the model structure to disaggregate subpopulations and incorporate multiple sources of risk20 may offer a better balance between model complexity and data availability and provide more actionable information, but will require additional effort, expense and time to develop.

Looking at new infections over 1 year may not highlight the underlying factors that drive an epidemic and, if the contribution of high-risk groups to the epidemic is underestimated in static, short-term modelling, then a portfolio of interventions based on these results may be sub-optimal for long-term control.28 Comparing the short-term predictions of the MOT model with dynamic transmission models could suggest how decision-making may have differed if it was based on determinants of long-term epidemic spread. One such comparison, in two distinct epidemics, illustrated how the MOT model can overestimate the contribution of low-risk groups and underestimate the contribution of commercial sex, thereby underestimating the longer-term preventive potential of targeted interventions for commercial sex workers.35

Moving forward, the current MOT process can be strengthened by better understanding of the limitations of the model and the data, by some modifications to the model structure and assumptions, and by careful and considered interpretation and application of its results.

Acknowledgements

We thank participants of the HIV Modelling Consortium: Rifat Atun, Imperial College London; Bertran Auvert, University of Versailles Saint Quentin en Yvelines; Nicolas Bacaer, IRD and University of Paris 6; Till Barnighausen, Harvard School of Public Health and University of KwaZulu–Natal; Anna Bershteyn, Intellectual Ventures; Marie-Claude Boily, Imperial College London; Wim Delva, South African Centre for Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis and Ghent University; Philip Eckhoff, Intellectual Ventures; Anna Foss, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; Janneke Heijne, University of Bern; Daniel J Klein, Intellectual Ventures; Nicola Low, University of Bern; Catherine M. Lowndes, Health Protection Agency, London; Sharmistha Mishra, Imperial College London; Carel Pretorius, Futures Institute; Alex Welte, South African Centre for Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis; Peter White, Imperial College London and Health Protection Agency, London; Brian Williams, South African Centre for Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis; David Wilson, The World Bank; David P Wilson, University of New South Wales; Basia Zaba, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; and Holly Prudden, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Competing interests:

Co-authors of this manuscript have acted as consultants for UNAIDS. The HIV Modelling Consortium is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through a grant to Imperial College London. The secretariat of the UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates, Modelling and Projections is funded by UNAIDS through a grant to Imperial College London.

References

- 1.Gouws E, White PJ, Stover J, Brown T. Short term estimates of adult HIV incidence by mode of transmission: Kenya and Thailand as examples. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(Suppl 3):iii51–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zambia HIV prevention response and modes of transmission analysis Lusaka: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS & The World Bank Global HIV/AIDS Program; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelmon L, Kenya P, Oguya F, Cheluget B, Haile G. Kenya HIV prevention response and modes of transmission analysis Nairobi: National AIDS Control Council; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khobotlo M, Tshehlo R, Nkonyana J, Ramoseme M, Khobotle M, Chitoshia A et al. Lesotho: HIV prevention response and modes of transmission analysis Maseru: National AIDS Commission; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.HIV modes of transmission model: analysis of the distribution of new HIV infections in the Dominican Republic and recommendations for prevention Santo Domingo: Consejo Presidencial del SIDA, Dirección General de Control de las Infecciones de Transmisión Sexual y Sida & Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mumtaz G, Hilmi N, Zidouh A, El Rhilani H, Alami K, Bennani A et al. HIV modes of transmission analysis in Morocco Rabat: Kingdom of Morocco Ministry of Health and National STI/AIDS Programme, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) & Weill Cornell Medical College Qatar; 2010.

- 7.Mngadi S, Fraser N, Mkhatshwa H, Lapidos T, Khumalo T, Tsela S et al. Swaziland HIV prevention response and modes of transmission analysis Mbabane: National Emergency Response Council on HIV and AIDS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wabwire-Mangen F, Kisitu DW. Uganda HIV modes of transmission and prevention response analysis Kampala: Uganda National AIDS Commission; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.New HIV infections by mode of transmission in West Africa: a multi-country analysis Dakar: UNAIDS Regional Support Team for West and Central Africa; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alarcón Villaverde JO. Modos de transmisión del VIH en América Latina: resultados de la aplicación del modelo Lima: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2009. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pisani E, Garnett GP, Grassly NC, Brown T, Stover J, Hankins C, et al. Back to basics in HIV prevention: focus on exposure. BMJ. 2003;326:1384–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown T, Peerapatanapokin W. The Asian epidemic model: a process model for exploring HIV policy and programme alternatives in Asia. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(Suppl 1):i19–24. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.010165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Actuarial Society of South Africa Aids Committee [Internet]. Models. Cape Town: ASSA; 2011. Available from: http://aids.actuarialsociety.org.za/404.asp?pageid=3145 [accessed 7 August 2012].

- 14.Brown T, Bao L, Raftery AE, Salomon JA, Baggaley RF, Stover J, et al. Modelling HIV epidemics in the antiretroviral era: the UNAIDS Estimation and Projection package 2009. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(Suppl 2):ii3–10. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.044784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Futures Institute [Internet]. Spectrum. Glastonbury: FI; 2012. Available from: http://futuresinstitute.org/Pages/spectrum.aspx [accessed 7 August 2012].

- 16.Colvin M, Gorgens-Albino M, Kasedde S. Analysis of HIV prevention response and modes of HIV transmission: the UNAIDS-GAMET-supported synthesis process Johannesburg: UNAIDS Regional Support Team Eastern and Southern Africa; 2008. Available from: http://www.unaidsrstesa.org/sites/default/files/modesoftransmission/analysis_hiv_prevention_response_and_mot.pdf [accessed 27 August 2012]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.How GAMET helps countries to improve their HIV response through epidemic, response and policy syntheses. In: HIV/AIDS M&E – getting results Washington: The World Bank Global HIV/AIDS Program; 2007. Available from: http://gametlibrary.worldbank.org/files/1602_GAMET_Synthesis.pdf [accessed 17 August 2012].

- 18.Practical guidelines for intensifying HIV prevention: towards universal access Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.HIV Modelling Consortium [Internet]. Sources of infections and national intervention impact projections. In: Report of meeting on surces of infections and national intervention impact projections, Montreux, 28–29 April 2011 Available from: http://www.hivmodelling.org/events/sources-infections-and-national-intervention-impact-projections [accessed 27 August 2012].

- 20.Foss AM, Prudden H, Mehl A, Zimmerman C, Ashburn K, Trasi R, et al. The UNAIDS modes of transmission model: a useful tool for decision making? Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:A167. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050108.160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Brookmeyer R, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2001;357:1149–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boily MC, Baggaley RF, Wang L, Masse B, White RG, Hayes RJ, et al. Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:118–29. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powers KA, Poole C, Pettifor AE, Cohen MS. Rethinking the heterosexual infectivity of HIV-1: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:553–63. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70156-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abu-Raddad L, Akala FA, Semini I, Riedner G, Wilson D, Tawil O. Characterizing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: time for strategic action: Middle East and North Africa HIV/AIDS epidemiology synthesis project Washington: The World Bank; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abu-Raddad LJ, Hilmi N, Mumtaz G, Benkirane M, Akala FA, Riedner G, et al. Epidemiology of HIV infection in the Middle East and North Africa. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 2):S5–23. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386729.56683.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hontelez JA, Lurie MN, Newell ML, Bakker R, Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, et al. Ageing with HIV in South Africa. AIDS. 2011;25:1665–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834982ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mishra S, Sgaier SK, Thompson L, Moses S, Ramesh BM, Alary M, et al. Revisiting HIV epidemic appraisals for assisting in the design of effective HIV prevention programs. In: 19th International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research Conference, Quebec City, 10–13 July 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guidelines on estimating the size of populations most at risk to HIV Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cáceres C, Konda K, Pecheny M, Chatterjee A, Lyerla R. Estimating the number of men who have sex with men in low and middle income countries. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(Suppl 3):iii3–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.019489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishra S, Sgaier SK, Thompson LH, Moses BM, Ramesh M, Alary JF. HIV epidemic appraisals for assisting in the design of effective prevention programmes: shifting the paradigm back to basics. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowndes CM, Jayachandran AA, Banandur P, Ramesh BM, Washington R, Sangameshwar BM, et al. Polling booth surveys: a novel approach for reducing social desirability bias in HIV-related behavioural surveys in resource-poor settings. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1054–62. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fenton KA, Johnson AM, McManus S, Erens B. Measuring sexual behaviour: methodological challenges in survey research. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:84–92. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.2.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips AE, Gomez GB, Boily MC, Garnett GP. A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative interviewing tools to investigate self-reported HIV and STI associated behaviours in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1541–55. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra S, Pickles M, Vickerman P, Blanchard JF, Moses S, Boily MC. Estimating the sources of infection in concentrated and generalized HIV epidemics: a comparative modeling analysis. Symposium on key populations and their role in STD/HIV transmission dynamics. In: 19th International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research Conference, Quebec City, 10–13 July 2011 [Google Scholar]