Abstract

Inflammation plays key roles at various stages of tumor development, including invasion and metastasis. In mice, the angiopoietin-like protein (ANGPTL2) gene has been implicated in inflammatory carcinogenesis. ANGPTL2 mRNA expression was investigated by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay using LightCycler in surgically treated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases. In total, 110 surgically resected NSCLC cases were used for mRNA level analyses. The ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA levels were not significantly different between lung cancer (1598.481±6465.781) and adjacent normal lung tissues (2116.639±8337.331, P=0.5453). The tumor/normal (T/N) ratio of ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA levels was not different between gender, age, smoking status and pathological stages. The T/N ratio of ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA levels was significantly higher in lymph node metastasis-positive cases (2.173±3.151) compared with lymph node metastasis-negative cases (1.212±1.778, P=0.0464). However, ANGPTL2 mRNA status was not correlated with tumor invasion status. Thus, ANGPTL2 may drive metastasis and provide a candidate for blockade of its function as a strategy to antagonize the metastatic process in NSCLC.

Keywords: ANGTL2, angiopoietin, lung cancer, metastasis, LightCycler

Introduction

Lung cancer is a major cause of mortality from malignant disease, due to its high incidence, malignant behavior and lack of major advancements in treatment strategy (1). Lung cancer was the leading indication for respiratory surgery (47.5%) in 2009 in Japan (2) and more than 30,000 patients underwent surgery for lung cancer at Japanese institutions in the same year (2). The clinical behavior of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is largely associated with its stage. NSCLC is only cured by surgery in cases that are in the early stages of the disease (3).

Recently, the theory that chronic inflammation plays a significant role in cancer development, including carcinogenesis, invasion and metastasis, has been proposed (4). It is well known that inflammation induced by environmental exposure, including tobacco smoking and inhaled pollutants (silica or asbestos), increase cancer risk (5–7). It has also been reported that chronic and subclinical levels of inflammation, for example, obesity-induced inflammation, may increase cancer risk (8). Angiopoietin-like protein 2 (ANGPTL2) is a causative mediator of chronic inflammation in obesity and its related metabolic abnormalities (9). ANGPTL2 is secreted by adipose tissue and the expression is increased during hypoxia and endoplasmic reticulum stress (9). The stress is commonly induced in cancer tissues in progression and metastasis (10). A previous study suggested that ANGPTL2 increased inflammatory carcinogenesis in a chemically induced skin squamous cell carcinoma mouse model (11). ANGPTL2 protein expression has also been reported in certain tumor cell types, including ovarian cancer (12), lung cancer (13) and sarcoma (14). Although the role of ANGPTL2 is controversial, ANGPTL2 may be a critical factor in cancer development.

The current study investigated ANGPTL2 mRNA expression in NSCLC and adjacent normal lung tissues using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using LightCycler (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) (15) in surgically treated cases. The findings were compared with the clinocopathological features of the NSCLC and ANGPTL2 gene status.

Patients and methods

Patients

The study group included NSCLC patients who had undergone surgery at the Department of Surgery, Nagoya City University Hospital between 2007 and 2009. All tumor samples were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C until assayed. The clinical and pathological characteristics of the 110 NSCLC patients for ANGPTL2 mRNA gene analyses were as follows: 70 (63.6%) were male, 40 were female; 89 cases (80.9%) were diagnosed as adenocarcinomas and 18 were diagnosed as squamous cell carcinomas; 69 (62.7%) were smokers, 41 were non-smokers and 73 (66.4%) were pathological stage I.

PCR assay for ANGPTL2 gene

Total RNA was extracted from NSCLC and adjacent normal lung tissues using an Isogen kit (Nippon gene, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration was determined by Nano Drop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Nano Drop Technologies Inc., Rockland, DE, USA). Approximately 10 cases were excluded in each assay as there were too few tumor cells to sufficiently extract tumor RNA. RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using a First strand cDNA synthesis kit with 0.5 μg oligo (dT)16 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction mixture was incubated at 25°C for 15 min, 42°C for 60 min, 99°C for 5 min and then at 4°C for 5 min. The cDNA concentration was determined by Nano Drop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer. Approximately 200 ng of each cDNA was used for PCR analysis. To ensure the fidelity of mRNA extraction and reverse transcription, all samples were subjected to qPCR amplification with a β-actin primers kit (Nihon Gene Laboratory, Miyagi, Japan) using LightCycler-FastStart DNA Master HybProbe kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH). The ANGTL2 qPCR assay reactions were performed using LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) in a 20-μl reaction volume. The primer sequences for the ANGPTL2 gene were as follows: forward primer, 5′-GCCACCAAGTGTCAGCCTCA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGGACAGTACCAAACATCCAACATC-3′ (134 bp). The cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 sec, 57°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 6 sec.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Student’s t-test for unpaired samples and Wilcoxon’s signed rank test for paired samples. Correlation coefficients were determined by rank correlation using Spearman’s test. The overall survival rate of lung cancer patients was examined by the Kaplan-Meier methods and differences were examined by the Log-rank test. All analyses were performed using the Stat-View software package (Abacus Concepts Inc. Berkeley, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant result.

Results

ANGPTL2 mRNA status in Japanese lung cancer patients

The ANGPTL2 gene status was quantified for 110 NSCLC samples and adjacent normal lung tissues. The ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA levels were not significantly different between lung cancer (1598.481±6465.781) and adjacent normal lung tissues (2116.639±8337.331, P=0.5453). The tumor/normal (T/N) ratio of the ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA level was not correlated with gender (male vs. female, P= 0.4284), age (age≤65 vs. >65, P= 0.8290) or smoking status (smoker vs. non-smoker, P=0.8879). The T/N ratio of the ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA level was not correlated with pathological stages and pathological subtypes (adenocarcinoma vs. others, P=0.2652). The T/N ratio of the ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA level was significantly higher in lymph node metastasis cases (2.173±3.151) when compared with the lymph node metastasis negative cases (1.212±1.778, P=0.0468) (Table I).

Table I.

Clinicopathological data of 110 lung cancer patients.

| Factors | No. of patients (%) | T/N ratio of ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA levels (mean ± SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | |||

| I | 73 (66.4) | 1.271±1.841 | NS |

| II | 16 (14.5) | 1.853±3.02 | |

| III–IV | 21 (19.1) | 1.893±2.895 | |

| Tumor status | |||

| T1 | 50 (45.5) | 1.285±2.070 | NS |

| T2 | 45 (40.9) | 1.603±2.283 | |

| T3 | 3 (2.7) | 3.867±5.077 | |

| T4 | 12 (10.9) | 1.182±2.046 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| Negative | 80 (72.7) | 1.212±1.778 | 0.0468 |

| Positive | 30 (27.3) | 2.173±3.151 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤65 | 53 (48.2) | 1.425±2.154 | 0.8290 |

| >65 | 57 (51.8) | 1.519±2.376 | |

| EGFR mutation | |||

| Positive | 29 (26.4) | 1.168±1.708 | 0.3976 |

| Negative | 81 (73.6) | 1.584±2.429 | |

| Smoking | |||

| BI=0 | 41 (37.3) | 1.434±1.991 | 0.8879 |

| BI>0 | 69 (62.7) | 1.498±2.422 | |

| Pathological subtypes | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 89 (80.9) | 1.413±2.037 | 0.5653 |

| Non-adenocarcinoma | 21 (19.1) | 1.731±3.089 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 70 (63.6) | 1.344±2.176 | 0.4284 |

| Female | 40 (36.4) | 1.701±2.417 |

T/N, tumor/normal; NS, not significant; BI, Brinkman index. The mean age of the 110 patients was 66.7±9.0 years.

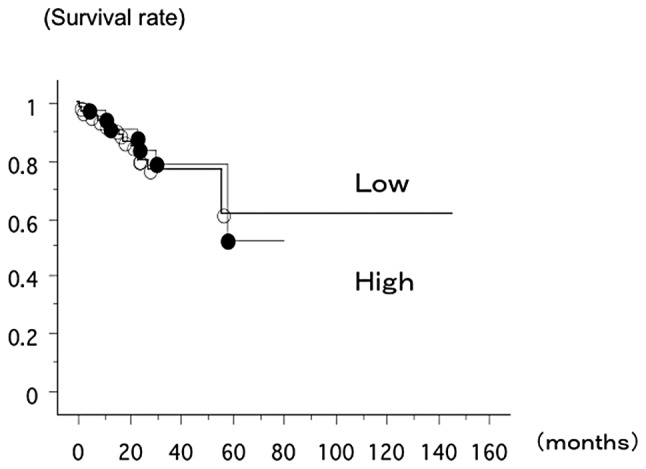

The overall survival rate of 110 lung cancer patients from Nagoya City University, with a follow up until August 31 2011, was studied in reference to the ANGPTL2 gene status. The survival rate of the patients with the T/N ratio of ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA level>1 (n=39, 7 had succumbed) and the patient within the T/N ratio of ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA level <1 (n=71, 13 had succumbed) was not significantly different (log-rank test, P=0.7564; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The overall survival rate of 110 lung cancer patients from Nagoya City University, with follow-up until August 31 2011, was studied in reference to the ANGPTL2 gene status. The survival rate of the patients with a T/N ratio of ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA level>1 (n=39, 7 had succumbed; ●) and patients with a T/N ratio of ANGPTL2/β-actin mRNA level <1 (n=71, 13 had succumbed; ○) was not significantly different (log-rank test, P=0.7944). T/N, tumor/normal.

Discussion

The current study focused on chronic inflammation (16) and the angiogenesis-related gene, ANGPTL2 (17). ANGPTL2 mRNA expression was correlated with lymph node metastasis in surgically resected NSCLC using LightCycler.

The increased accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen intermediates caused by chronic inflammation may inactivate DNA repair enzymes (18). Previous studies have suggested that the chronic inflammation status and ROS levels were positively correlated with ANGPTL2 expression levels (11). ANGPTL2 expression was highly correlated with the frequency of carcinogenesis in a chemically induced skin squamous cell carcinoma in mice (11).

The ANGPTL2 gene has been reported to act as a tumor suppressor in ovarian cancer (4). Decreased ANGPTL2 expression was associated with a worse prognosis in stage I and II disease, whereas ANGPLT2 positivity was significantly associated with a worse survival rate in stage III and IV disease (4). Thus, ANGPTL2 may also act as a molecule for tumor progression and metastasis in advanced stage disease. In a xenograft mouse model, tumor cell-derived ANGPTL2 accelerated metastasis and shortened the survival rate, whereas attenuating ANGPTL2 expression in tumor cells inhibited metastasis and extended the survival rate (13). ANGPTL2 expression was high and homogeneous in tumor cells within metastasized tumor sites (13). In our analysis, ANGPTL2 expression correlated with metastasis but not tumor invasion. The tumor cells expressing ANGPTL2 may exhibit high metastatic potential.

A recent study has reported that the ANGPTL2 gene promoted vascular inflammation (19) and enhanced endothelial cell migration (20). The expression of cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (21), interlukin-6 and interleukin-1β, were found to be increased in ANGPTL2 transgenic mice (19). The ANGPTL2-null mice survived and grew normally. Thus it is predicted that the suppression of ANGPTL2 signaling has few side-effects. Therefore the suppression of ANGPLT2 signaling as a therapeutic strategy is likely to be beneficial (20).

However, if the study were expanded, it would not be possible to perform qPCR in the majority of patients since the availability of tumor samples in the cohort was limited. The majority of patients with advanced stage NSCLC had only small tissue samples and the samples were mostly used for clinical diagnosis, leaving limited residual samples for molecular diagnosis. ANGPTLs have a signal sequence in the N-terminals for protein secretion (20). ANGPTL2 is predominantly secreted from adipose tissue and the heart (22). Cells transfected with expression vectors encoding ANGPTLs secreted ANGPTLs proteins into culture supernatants (23,24). ANGPTLs have been detected in the systemic circulation (23,24), suggesting that the detection of ANGPTL2 in blood samples may be useful for cancer patients. Thus, the development and validation of strategies to improve effective identification of the patient population with strategies incorporating immunohistochemistry (IHC) or other techniques are important and likely to assume a place in clinical practice. A prospective study is required to compare the usage of RT-PCR, IHC and detection from blood samples.

In summary, ANGPTL2 may drive metastasis and provide a candidate for blockade of its function as a strategy to antagonize the metastatic process. The result of RT-PCR was validated in a limited number of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Yuka Toda for her excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS, Nos, 24592097, 23659674) and a grant for cancer research of Program for developing the supporting system for upgrading the education and research (2009) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

- 1.Ginsberg RJ, Kris MK, Armstrong G, editors. Cancer of the lung In: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 4th edition. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1993. pp. 673–682. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakata R, Fujii Y, Kuwano H. Thoracic and cardiovascular surgery in Japan during 2009: annual report by the Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;59:636–667. doi: 10.1007/s11748-011-0838-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Postmus PE. Chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: the experience of the Lung Cancer Cooperative Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Chest. 1998;113:28S–31S. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.1_supplement.28s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Martel C, Franceschi S. Infections and cancer: established associations and new hypotheses. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;70:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi H, Takahashi I, Honma M, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Japanese psoriasis patients. J Dermatol Sci. 2010;57:143–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Destert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, et al. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kant P, Hull MA. Excess body weight and obesity-the link with gastrointestinal and hepatobilliary cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:224–238. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabata M, Kadomatsu T, Fukuhara S, et al. Angiopoietin-like protein 2 promotes chronic adipose tissue inflammation and obesity-related systemic insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;10:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bi M, Naczki C, Koritzinsky M, et al. ER stress-regulated translation increases torelance to extreme hypoxia and promotes tumor growth. EMBO J. 2005;24:3470–3481. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoi J, Endo M, Kadomatsu T, et al. Angiopoietin-like protein 2 is an important facilitator of inflammatory carcinogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7502–7512. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kikuchi R, Tsuda H, Kozaki K, et al. Frequent inactivation of a putative tumor suppressor, angiopoietin-like protein 2, in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5067–5075. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endo M, Nakano M, Kadomatsu T, et al. Tumor cell-derived angiopoietin-like protein ANGPTL2 is a critical driver of metastasis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1784–1794. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teicher BA. Searching for molecular targets in sarcoma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wittwer CT, Ririe KM, Andrew RV, et al. The LightCycler: a microvolume multi sample fluorimeter with rapid temperature control. Biotechniques. 1997;22:176–181. doi: 10.2144/97221pf02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogata A, Endo M, Aoi J, et al. The role of angiopoietin-like protein 2 in pathogenesis of dermatomyositis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418:494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tazume H, Miyake K, Tian Z, et al. Macropage-derived angiopoietin-like protein 2 accelerates development of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1400–1409. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.247866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1073–81. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadomatsu T, Tabata M, Oike Y. Angiopoietin-like proteins: emerging targets for treatment of obesity and related metabolic disease. FEBS J. 2011;278:559–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabata M, Kadomatsu T, Fukuhara S, et al. Angiopoietin-like protein 2 promotes chronic adipose tissue inflammation and obesity-related systemic insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;10:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng JY, Zou JT, Wang WZ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α a increases angiopoietin-like 2 gene expression by activating Foxo1 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;339:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitazawa M, Nagono M, Masumoto KH, et al. Angiopoietin-like 2, a circadian gene, improves type 2 diabetes through potentiation of insulin sensitivity. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2558–2567. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim I, Moon SO, Koh KN, et al. Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of angiopoietin-related protein. Angiopoietin-related protein induces endothelial cell spouting. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26523–26528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oike Y, Ito Y, Maekawa H, et al. Angiopoietin-related growth factor (AGF) promotes angiogenesis. Blood. 2004;103:3760–3765. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]