Abstract

Head and neck cancer is a significant health problem worldwide. Early detection and prediction of prognosis will improve patient survival and quality of life. The aim of this study was to identify genes differentially expressed between laryngeal cancer and the corresponding normal tissues as potential biomarkers. A total of 36 patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma were recruited. Four of these cases were randomly selected for cDNA microarray analysis of the entire genome. Using semi-quantitative RT-PCR and western blot analysis, the differential expression of genes and their protein products, respectively, between laryngeal cancer tissues and corresponding adjacent normal tissues was verified in the remaining 32 cases. The expression levels of these genes and proteins were investigated for associations with clinicopathological parameters taken from patient data. The cDNA microarray analysis identified 349 differentially expressed genes between tumor and normal tissues, 112 of which were upregulated and 237 were downregulated in tumors. Seven genes and their protein products were then selected for validation using RT-PCR and western blot analysis, respectively. The data demonstrated that the expression of SENP1, CD109, CKS2, LAMA3, ITGAV and ITGB8 was increased, while LAMA2 was downregulated in laryngeal cancer compared with the corresponding normal tissues. Associations between the expression of these genes and clinicopathological data from the patients were also established, including age, tumor classification, stage, differentiation and lymph node metastasis. Our current study provides the first evidence that these seven genes may be differentially expressed in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma and also associated with clinicopathological data. Future study is required to further confirm whether detection of their expression can be used as biomarkers for prediction of patient survival or potential treatment targets.

Keywords: cDNA microarray, gene expression, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Head and neck cancer is the sixth most common type of cancer in the world, accounting for more than 540,000 new cases and 271,000 mortalities each year (1). These cancers occur in the lips, oral cavity, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, pharynx and larynx, 90% of which are squamous cell carcinomas. They significantly affect long-term survival and the quality of life of patients. The development of novel strategies is required for prevention and early detection, to reduce cancer incidence and overcome problems associated with treatment of late-stage tumors. Improved prediction of outcome will lead to treatment decisions that prolong patients’ survival and quality of life.

Predictions concerning the outcome of head and neck cancers are currently based mostly on clinicopathological features, including tumor stage, differentiation, size and regional lymph node or distant metastasis. However, increasing numbers of studies utilize aberrant gene expression and genomic and epigenetic alterations to predict prognosis.

It has been established that tobacco smoke and alcohol consumption are the most significant risk factors for head and neck cancers. They contribute to these cancers through multiple genetic alterations, including the silencing of tumor suppressor genes and oncogene activation (2). A large body of knowledge has accumulated regarding gene alterations that are associated with the development of this deadly disease. However, greater understanding of the links between gene alteration and head and neck cancer development and progression is required.

DNA microarray profiling is an innovative technology that facilitates analysis of a great number of genes simultaneously. In this study, we performed an analysis of nearly the entire human genome in order to detect altered gene expression between primary laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) and adjacent normal tissues. We identified 349 genes that are differentially expressed between normal and malignant tissues, a number of which have not previously been associated with LSCC. Thus, we selected specific tumor-related genes from microarray data, which have not been reported in LSCC before. We then verified the differential expression of the seven genes in another set of LSCC tissues. In the future, these genes may be further evaluated as biomarkers or potential therapeutic targets for LSCC.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Between October 2007 and March 2010, tissue biopsy specimens (tumor and matched adjacent normal tissues) were collected from 36 patients (Table I) with LSCC at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Drum Tower Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University School of Medicine (Nanjing, China). Pathological analyses confirmed the diagnosis of each patient. The tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Our institutional Human Ethics Committee approved the study. Informed consent was obtained either from the patient or the patient’s family.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of LSCC cases studied.a

| Case no. | Age (years) | Tobacco use | Alcohol use | Tumor classification | Tumor differentiation | TNM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSCC-001 | 71 | Yes | No | Supra-GC | M | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-002 | 62 | Yes | No | SGC | M | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-003 | 61 | Yes | Yes | SGC | W | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-004 | 63 | Yes | No | GC | W | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-005 | 52 | Yes | Yes | Supra-GC | M | T4N0M0 |

| LSCC-006 | 75 | Yes | No | Supra-GC | P | T3N1M0 |

| LSCC-007 | 74 | Yes | No | GC | W | T4N0M0 |

| LSCC-008 | 59 | Yes | No | GC | W | T4N0M0 |

| LSCC-009 | 59 | Yes | Yes | GC | P | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-010 | 68 | No | No | GC | M | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-011 | 57 | Yes | Yes | Supra-GC | W | T2N0M0 |

| LSCC-012 | 84 | No | No | Supra-GC | P | T4N2M0 |

| LSCC-013 | 66 | Yes | No | Supra-GC | M | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-014 | 74 | No | No | Supra-GC | M | T3N2M0 |

| LSCC-015 | 49 | Yes | No | Supra-GC | P | T3N1M0 |

| LSCC-016 | 54 | Yes | Yes | GC | W | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-017 | 73 | No | No | Sub-GC | M | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-018 | 53 | Yes | No | GC | W | T4N0M0 |

| LSCC-019 | 54 | Yes | No | Supra-GC | P | T4N1M0 |

| LSCC-020 | 70 | Yes | No | Supra-GC | P | T4N2M0 |

| LSCC-021 | 58 | Yes | Yes | Supra-GC | M | T4N2M0 |

| LSCC-022 | 63 | Yes | Yes | Supra-GC | M | T2N0M0 |

| LSCC-023 | 54 | Yes | Yes | Supra-GC | M | T1N0M0 |

| LSCC-024 | 60 | Yes | Yes | Supra-GC | P | T3N2M0 |

| LSCC-025 | 53 | Yes | No | Sub-GC | M | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-026 | 59 | Yes | Yes | GC | W | T4N0M0 |

| LSCC-027 | 60 | Yes | Yes | GC | W | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-028 | 75 | Yes | Yes | Supra-GC | M | T3N1M0 |

| LSCC-029 | 57 | Yes | Yes | GC | W | T1N0M0 |

| LSCC-030 | 63 | Yes | No | GC | W | T1N0M0 |

| LSCC-031 | 66 | Yes | Yes | Supra-GC | W | T2N0M0 |

| LSCC-032 | 52 | Yes | Yes | Supra-GC | M | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-033 | 40 | Yes | No | GC | M | T3N0M0 |

| LSCC-034 | 75 | No | No | GC | P | T1N0M0 |

| LSCC-035 | 73 | Yes | Yes | GC | M | T1N0M0 |

| LSCC-036 | 70 | Yes | Yes | GC | M | T2N0M0 |

All subjects were male. GC, glottic carcinoma; Sub-GC, subglottic carcinoma; Supra-GC, supraglottic carcinoma. P, poorly differentiated; M, moderately differentiated; W, well-differentiated. LSCC, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

RNA isolation and microarray analysis

To isolate RNA from the tissue specimens, both tumor and normal mucosae were put into liquid nitrogen and ground into powder in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using a rotor-stator homogenizer. Total RNA was then isolated following the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of the RNA was verified by visual inspection after 1% agarose gel electrophoresis; the 28S ribosomal RNA band intensity was two times that of the 18S ribosomal RNA band (3). Sample purity was ensured by an OD260/OD280 ratio >1.8, measured with a spectrophotometer.

For DNA microarray analysis, biotinylated probes were prepared using 2 μg of total RNA. Briefly, the total RNA obtained from tumor and normal tissues was mixed with 100 pmol of T7-oligo(dT)24 primer and denatured at 70°C for 10 min, then chilled on ice. The first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and the second-strand with DNA Polymerase I, E. coli DNA ligase and RNase H. The biotinylated probes were then prepared from the entire cDNA reaction using an ENZO Bioarray High Yield RNA Transcript Labeling kit (ENZO Diagnostics, Toronto, Canada).

The purified probes were incubated with 1X fragmentation buffer at 95°C for 35 min to reduce the average probe length. Hybridization was performed at 45°C for 20 h with biotinylated probes on the microarrays. The non-specific binding of these probes was removed by low stringency washes (10 times) and high stringency washes (4 times) using a GeneChip Fluidics Station 400 wash station (Agilent, San Diego, CA, USA). The positive signal was detected by incubating the microar-rays with streptavidin phycoerythrin (Molecular Probes, Camarillo, CA, USA) and scanned with a GeneArray Scanner (Hewlett-Packard, San Diego, CA, USA). The scanned data were analyzed with GeneChip Analysis Suite 3.3 (Agilent).

Semi-quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

To confirm the differential gene expression of laryngeal cancer revealed during cDNA microarray analysis, we used a 2-step method of semi-quantitative RT-PCR starting with tissues from 32 cases of laryngeal cancer and matched normal adjacent tissues. Briefly, total RNA was first reverse transcribed into cDNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) and then amplified in a programmable Applied Biosystems 2720 thermal cycler (Singapore). For each reaction, a 50-μl PCR mixture containing 200 μM dNTPs, 1.25 units Taq polymerase in 10X Taq polymerase buffer (Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan), and corresponding concentrations of primers (Table II) was set to an initial denaturing at 95°C for 5 min and then appropriate PCR cycles for different genes of 94°C for 1 min, annealing temperature (Table II) for 1 min, 72°C for 30 sec and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min in a programmable 2720. The PCR reactions were performed in triplicate.

Table II.

Primer sequences and PCR conditions.

| Gene | Primer sequences | Annealing temperature (°C) | No. PCR cycles | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SENP1 | 5′-ACCCACCTCCTGCCACAAAC-3′ | 60 | 36 | 424 |

| 5′-TTCGACGACATGAACCACTCCA-3′ | ||||

| CD109 | 5′-AAGCCTTTGATTTAGATGTTGC-3′ | 60 | 36 | 445 |

| 5′-GAGTGATGATGGGAGCCTGA-3′ | ||||

| CKS2 | 5′-CAAGCAGATCTACTACTCGG-3′ | 56 | 36 | 222 |

| 5′-TGGAAGAGGTCGTCTAAAGA-3′ | ||||

| LAMA3 | 5′-TTCATGGGATACAGAGAGGT-3′ | 58 | 36 | 446 |

| 5′-TTGGAGAAACAAGGACAGAG-3′ | ||||

| LAMA2 | 5′-AATTTACCTCCGCTCGCTAT-3′ | 60 | 36 | 424 |

| 5′-CCTCCAATGTACTTTCCACG-3′ | ||||

| ITGAV | 5′-CTGGGATTGTGGAAGGAGGG-3′ | 60 | 36 | 462 |

| 5′-TGCTGTAAACATTGGGGTCG-3′ | ||||

| ITGB8 | 5′-TGGGCCAAGGTGAAGACAAT-3′ | 60 | 36 | 456 |

| 5′-ATGAGCCAAATCCAAGACGA-3′ | ||||

| β-actin | 5′-TCGACAACGGCTCCGGCAT-3′ | 56 | 28 | 241 |

The PCR-amplified gene products were visualized in a 2% (w/v) agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Images of resulting gels were captured with LabWorks45 (UVP, Upland, CA, USA). The genes detected by PCR were SENP1, CD109, CKS2, LAMA2, LAMA3, ITGAV, ITGB8 and β-actin (Table II). β-actin was used as the loading control and normalizing reference for each gene in these tissue samples. The primers were designed according to their GenBank sequences using the Primer 3 online tool.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Both LSCC and the matched adjacent normal tissues were homogenized for total cellular protein extraction using a commercial protein kit from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL, USA). The protein concentration of the homogenates was determined by a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Shenergy Biocolor, Shanghai, China).

Equal amounts of the protein samples (50 μg) were separated via 10–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), followed by electrophoretic transfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). These membranes were incubated with 5% non-fat milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 2 h and then with the primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies CKS2 (#ab54658) and SENP1 (#ab3656) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). CD109 (#SC33115) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The next day, the membranes were washed with PBS 3 times and then incubated with an anti-goat or anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The immunoreactive signals were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce Biotechnology) and quantified with a densitometer (Kodak Digital Science 1D Analysis Software, Rochester, NY, USA).

Statistical analysis

DNA microarray data were analyzed using the Agilent GeneChip Analysis Suite 3.3 and summarized as fold changes. The data from semi-quantitative RT-PCR and western blot analysis were summarized as percentages of controls. The differential expression levels of genes between the tumor and normal tissues were statistically analyzed with paired-sample t-tests using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The association of gene expression levels with clinicopathological data was statistically analyzed with an independent-samples t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Detection of differentially expressed genes between the primary LSCC and corresponding normal tissues

In this study, we first randomly selected 4 pairs of primary laryngeal cancer and corresponding normal tissues for DNA microarray analysis. We then isolated RNA from the frozen tissues and performed DNA microarray analysis in Agilent chips. We identified that 10,909 genes were differentially expressed between laryngeal cancer and the matched normal tissues in case 1; 10,223 genes in case 2; 5,730 genes in case 3; and 14,665 genes in case 4. Among these differentially expressed genes, there were 349 that were identified in all four cases, of which 112 were significantly upregulated with intensity ratios up 2.0, while 237 were downregulated with ratios down 0.5 (Table III).

Table III.

Differentially expressed genes between primary laryngeal cancer and corresponding normal tissues.

| GenBank accession no. | Gene name | Gene symbol | Potential functions | Fold changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK091217 | Amine oxidase (flavin containing) domain 1 | AOF1 | Transcription | 4.157 |

| AB037807 | Ankyrin repeat and IBR domain containing 1 | ANKIB1 | Signaling | 3.332 |

| NM_019862 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 1 | ABCC1 | Signaling | 3.012 |

| AL834478 | CD109 antigen (Gov platelet alloantigens) | CD109 | Signaling | 3.448 |

| NM_001274 | CHK1 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) | CHEK1 | Cell cycle | 4.564 |

| NM_001827 | CDC28 protein kinase regulatory subunit 2 | CKS2 | Cell cycle | 3.336 |

| NM_018098 | Epithelial cell transforming sequence 2 oncogene | ECT2 | Signaling | 5.918 |

| NM_000165 | Gap junction protein, α 1, 43 kDa (connexin 43) | GJA1 | Signaling | 5.305 |

| NM_005329 | Hyaluronan synthase 3 | HAS3 | Metabolism | 5.493 |

| NM_002210 | Integrin, α V (vitronectin receptor) | ITGAV | Adhesion | 3.778 |

| BC002630 | Integrin, β 8 | ITGB8 | Adhesion | 5.953 |

| X85108 | Laminin, α 3 | LAMA3 | Cell structure | 2.707 |

| NM_022045 | Mdm2, transformed 3T3 cell double minute 2 | Mdm2 | Apoptosis | 4.994 |

| BC004887 | LanC lantibiotic synthetase component C-like 2 | LANCL2 | Transcription | 2.667 |

| NM_014554 | SUMO1/sentrin specific protease 1 | SENP1 | Transcription | 2.688 |

| AF061512 | Tumor protein p73-like | TP73L/P63 | Cell cycle | 5.089 |

| NM_000667 | Alcohol dehydrogenase 1A (class I) | ADH1A | Metabolism | 0.109 |

| NM_000669 | Alcohol dehydrogenase 1C (class I) | ADH1C | Metabolism | 0.045 |

| NM_032827 | Atonal homolog 8 (Drosophila) | ATOH8 | Transcription | 0.216 |

| NM_006763 | BTG family, member 2 | BTG2 | Transcription | 0.274 |

| NM_175709 | Chromobox homolog 7 | CBX7 | Transcription | 0.305 |

| NM_005064 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 23 | CCL23 | Signaling | 0.219 |

| NM_006274 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 19 | CCL19 | Signaling | 0.215 |

| NM_005756 | G protein-coupled receptor 64 | GPR64 | Signaling | 0.074 |

| M65062 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 | IGFBP5 | Signaling | 0.253 |

| L36531 | Integrin, α 8 | ITGA8 | Adhesion | 0.395 |

| NM_138284 | Interleukin 17D | IL17D | Signaling | 0.123 |

| NM_000426 | Laminin, α 2 | LAMA2 | Cell structure | 0.293 |

| NM_005924 | Mesenchyme homeo box 2 | MEOX2 | Transcription | 0.136 |

| AK090729 | Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type II, β | SCN2B | Signaling | 0.163 |

| NM_003256 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 4 | TIMP4 | Growth factors | 0.2 |

Validation of microarray data using semi-quantitative RT-PCR or western blot analysis

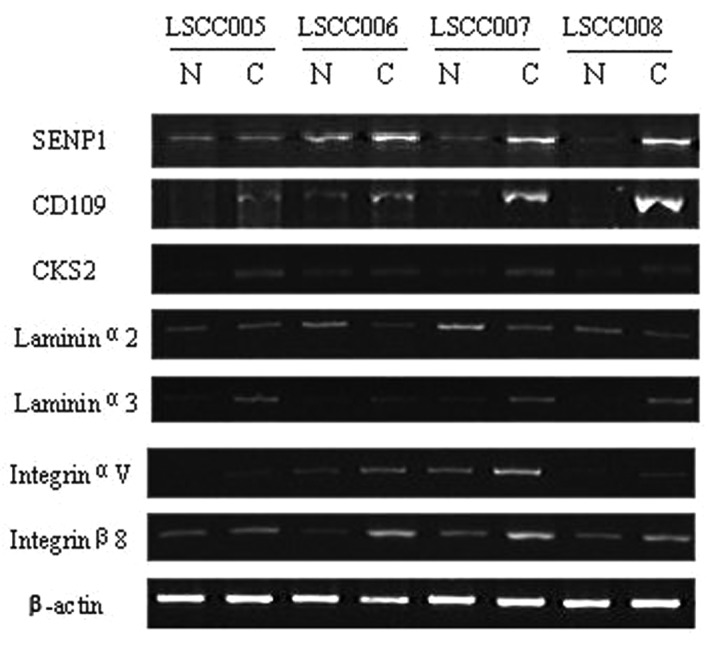

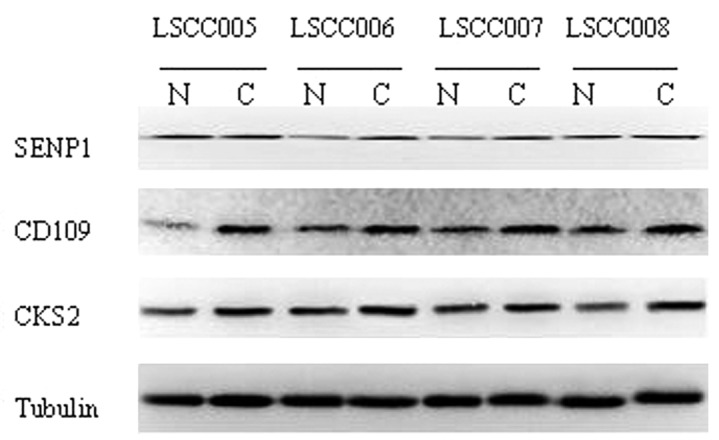

From the microarray data we chose 7 genes whose differential status was validated with semi-quantitative RT-PCR or western blot analysis, using source material from 32 cases of laryngeal cancer and the corresponding normal tissues. The results demonstrated that expression of these 7 genes were in accordance with the microarray data (Figs. 1 and 2). Expression levels of SENP1, CD109, CKS2, LAMA3, ITGAV and ITGB8 mRNA were all increased compared with the normal tissues, while LAMA2 mRNA was significant decreased in tumor tissues compared with normal tissues. As shown in Table IV, of the 32 laryngeal cancers, compared with normal epithelial tissues mRNA expression of SENP1 was significantly elevated in 22 cases (68.8%), LAMA3 in 23 (71.9%), CD109 in 26 (81.3%), CKS2 in 25 (78.1%), ITGAV in 22 (68.8%) and ITGB8 in 20 (62.5%), while LAMA2 was significantly less in 18 (56.3%). Western blot data showed that of these 32 laryngeal cancer tissues, compared with the corresponding normal tissues, SENP1 protein levels were markedly higher in 21 cases (65.6%), CD109 in 24 (75%) and CKS2 in 23 (71.9%; Table V).

Figure 1.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of differential gene expression in 32 cases of LSCC and matched normal tissue specimens. Total RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-PCR analysis. LSCC, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; N, normal tissues; C, tumor tissues.

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of selected gene expression in 32 cases of LSCC and the matched normal tissue specimens. Total cellular protein was extracted and subjected to western blot analysis. LSCC, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma; N, normal tissues; C, tumor tissues.

Table IV.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of gene expression.

| Gene | LSCC tissues | Related adjacent normal tissues | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SENP1 | 0.540±0.248 | 0.395±0.327 | 0.013 |

| CD109 | 0.941±0.452 | 0.293±0.294 | 0.000 |

| CKS2 | 13.895±4.787 | 10.351±4.297 | 0.000 |

| LAMA2 | 7.085±4.382 | 11.967±7.298 | 0.000 |

| LAMA3 | 6.276±3.922 | 2.849±3.723 | 0.002 |

| ITGAV | 1.013±0.478 | 0.759±0.468 | 0.019 |

| ITGB8 | 1.736±1.385 | 1.227±0.936 | 0.033 |

RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; LSCC, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Table V.

Western blot analysis of SENP1, CD109 and CKS2 protein expression in laryngeal cancer and the corresponding adjacent normal tissues.

| Protein | LSCC tissues | Related adjacent normal tissues | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SENP1 | 0.987±0.257 | 0.775±0.237 | 0.003 |

| CD109 | 1.827±0.676 | 1.606±0.746 | 0.021 |

| CKS2 | 0.827±0.389 | 0.628±0.252 | 0.013 |

LSCC, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Association of the expression of three genes with patient clinicopathological data

Statistical analysis revealed that protein levels of the three genes SENP1, CD109 and CKS2 were significantly different between tumor and corresponding normal tissues (P≤0.05). We examined their expression levels for associations with clinicopathological data, including age and tumor classification, stage, differentiation and lymph node metastasis (Table VI). SENP1 expression differed between stage I+II and III+IV tumors. CKS2 expression differed with tumor classification, tumor differentiation and lymph node metastasis. CD109 expression differed between glottic carcinoma and subglottic carcinoma.

Table VI.

Table IV. Association of SENP1, CD109 and CKS2 expression levels with patient clinicopathological data.

| SENP1

|

CKS2

|

CD109

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | No. | Mean ± SD | P-value | Mean ± SD | P-value | Mean ± SD | P-value |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| ≤62 | 17 | 1.000±0.246 | 0.793 | 0.862±0.325 | 0.472 | 1.868±0.619 | 0.612 |

| >62 | 15 | 1.020±0.156 | 0.770±0.392 | 1.968±0.450 | |||

| Tumor classification | |||||||

| Supra-GC | 16 | 1.012±0.154 | 0.989a | 0.938±0.441 | 0.040a | 1.906±0.573 | 0.523a |

| GC | 14 | 1.013±0.263 | 0.792b | 0.674±0.177 | 0.158b | 2.029±0.447 | 0.028b |

| Sub-GC | 2 | 0.959±0.290 | 0.678c | 0.882±0.260 | 0.866c | 1.187±0.524 | 0.112c |

| Tumor differentiation | |||||||

| Well | 10 | 1.030±0.257 | 0.857d | 0.626±0.256 | 0.068d | 1.906±0.671 | 0.679d |

| Moderate | 14 | 1.020±0.148 | 0.690e | 0.900±0.394 | 0.906e | 2.004±0.353 | 0.378e |

| Poor | 8 | 0.980±0.244 | 0.656f | 0.919±0.329 | 0.049f | 1.770±0.665 | 0.674f |

| Tumor stage | |||||||

| I+II | 9 | 0.920±0.102 | 0.047 | 0.689±0.493 | 0.212 | 2.063±0.457 | 0.339 |

| III+IV | 23 | 1.050±0.227 | 0.870±0.282 | 1.857±0.568 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | |||||||

| Yes | 9 | 1.030±0.193 | 0.750 | 1.039±0.358 | 0.026 | 1.935±0.504 | 0.897 |

| No | 23 | 1.000±0.214 | 0.733±0.322 | 1.907±0.564 | |||

Compared with glottic carcinoma.

Compared with subglottic carcinoma.

Compared with supraglottic carcinoma.

Compared with moderately differentiated.

Compared with poorly differentiated.

Compared with well-differentiated. GC, glottic carcinoma; Sub-GC, subglottic carcinoma; Supra-GC, supraglottic carcinoma.

Discussion

A profile of the genes that were differentially expressed between laryngeal cancers and corresponding normal mucosae was created using cDNA microarray analysis. A total of 349 differentially expressed genes were identified in four patients, of which 112 were significantly upregulated and 237 were downregulated. We also identified certain genes that were altered in LSCC, including P63 and Mdm2. We also found other genes that were altered in human cancers, but which have not been identified before in LSCC. Thus, we selected 7 genes to study the differential mRNA and protein expression in LSCC using semi-quantitative RT-PCR and western blot analysis, respectively. The data demonstrated that, compared with the normal mucosae, 6 of the 7 genes were upregulated in laryngeal cancer and 1 was downregulated.

Associations between these genes and clinicopathological data from the patients were identified. For example, the expression of SENP1 was associated with tumor stage, while CKS2 was associated with tumor classification, differentiation and lymph node metastasis. These results imply that the detection of elevated levels of expression of SENP1 and CKS2 should be further evaluated as tumor markers for early detection or prognosis of laryngeal cancer.

The identification of genes differentially expressed between normal and malignant tissues is the first step to understanding how altered expression may contribute to tumorigenesis. These genes are likely to represent critical points of alteration in pathways that regulate the cell cycle, cell-cell adhesion and cell motility. Our current data identified a large number of genes differentially expressed in tumor tissues compared with normal tissues of the larynx. Specifically, in 4 cancer cases there were 10,909, 10,223, 5,730 and 14,665 differentially expressed genes. Only 349 genes were identified to be differentially expressed in all 4 cases. These data indicate that each patient has an individualized profile with genes that may be targeted for personalized medical treatment in future studies. However, there are also genes that are commonly altered in laryngeal cancer that may be evaluated as biomarkers for early detection and prediction of prognosis of laryngeal cancer.

Of the genes whose expression is commonly elevated in laryngeal cancer, the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) is involved in numerous cellular processes, including nuclear-cytosolic transport, transcriptional regulation, apoptosis, protein stability, response to stress and progression through the cell cycle (4). The family of sentrin/SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs) is one of a group of enzymes that process newly synthesized SUMO1s into the conjugate form and catalyze the deconjugation of SUMO-containing species to regulate the function of the SUMO protein. SENP1, a member of the SENP family, has been reported to be overexpressed in colon cancer tissues (5) and has been demonstrated to regulate androgen receptor transactivation by targeting histone deacetylase I, and induce c-Jun activity through de-SUMOylation of p300 (6). Previous studies have demonstrated that SENP1 was able to transform normal prostate epithelium into a dysplasia, and also directly modulate several oncogenic pathways in prostate cells (7,8). However, it remains unknown whether and how the expression of SENP1 plays a role in laryngeal cancer.

In the present study, we identified that SENP1 mRNA and protein were highly expressed in laryngeal cancer tissues. SENP1 expression was also statistically different between stage I+II and III+IV tumors. Together, these findings indicate that SENP1 may play a role in tumorigenesis and progression of laryngeal cancer.

CD109 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked glycoprotein which belongs to the α2 macroglobulin/C3/C4/C5 family of thioester-containing proteins. A previous study revealed that CD109 was a useful diagnostic marker for basal-like breast carcinoma (9). Another study identified that CD109 may be involved in bladder tumorigenesis and might be a potential target for cancer immunotherapy (10). Zhang et al (11) detected CD109 expression in half of lung squamous cell carcinomas cases investigated, but not in lung adenocarcinomas, large cell carcinomas or small cell carcinoma. In addition, CD109 expression was found to be upregulated in approximately 50% of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cases. In the present study, we identified that CD109 was highly expressed in laryngeal cancer tissues, and CD109 expression differed between glottic carcinoma and subglottic carcinoma. However, the number of cases of subglottic carcinoma in this study were too few to make a definitive statement; these data require confirmation with additional studies with larger sample sizes.

CKS2, an essential component of cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase complexes, contributes to cell cycle progression. Earlier studies identified CKS2 as a transcriptional target that was downregulated by the tumor suppressor p53 (12). Other studies demonstrated that expression of CKS1 and CKS2 were elevated in prostate cancer, while knockdown of CKS2 expression induced programmed cell death and inhibited tumorigenicity (13). Another study demonstrated that CKS2 was significantly expressed in metastasized tumors (14). Using oligomicroarray analysis and qRT-PCR, Uchikado et al (15) identified CKS2 as a gene associated with the lymph node metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. The present study also revealed that CKS2 was highly expressed in laryngeal cancer and associated with tumor classification, tumor differentiation and lymph node metastasis.

Laminin, a basement membrane protein consisting of α, β and γ chains, plays a critical role in the maintenance of tissue structures (16). Laminin expression is a prerequisite for normal embryonic development (17). Abnormal expression of LAMA332 and its integrin receptors is a hallmark of certain types of tumor and is considered to promote the invasion of colon, breast and skin cancer cells (18). Our present study confirmed these previous findings, although its role in laryngeal cancer requires further study.

Integrins are a group of cell adhesion molecules that regulate a wide variety of dynamic cellular processes, including cell migration, phagocytosis, growth and embryonic development. The interaction of integrins with extracellular ligands is regulated from inside the cell through the short cytoplasmic α- and β-integrin tails, and transmits biochemical and mechanical signals to the cytoskeleton to change cell shape, behavior and fate (19). ITGAVB6 has a role in the inhibition of colon cancer cell apoptosis through targeting the mitochondrial pathway (20). Another study (21) demonstrated that antisense ITGAV and ITGB3 inhibited tumor vascularization and growth, but enhanced the apoptosis of tumor cells. Antisense ITGAV suppressed tumor growth more markedly than antisense ITGB3. Loss of the ITGB8 subunit resulted in abnormal blood vessel development in the yolk sac, placenta and brain (22); animals lacking the ITGB8 gene die either at mid-gestation (due to insufficient vascularization of the placenta and yolk sac) or shortly after birth with severe intra-cerebral hemorrhage (22). Our present study also demonstrated altered expression of these integrins in laryngeal cancer.

In conclusion, our study provides the first evidence that SENP1, CD109, CKS2, LAMA2, LAMA3, ITGAV and ITGB8 are differentially expressed in laryngeal cancer tissue specimens. Further study of these seven genes may aid the understanding of the multistep process of laryngeal tumorigenesis, and evaluate them as tumor biomarkers for early detection or prediction of prognosis of laryngeal cancer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr J.D. Wu of Nanjing Medical University for his helpful advice and Mr. J.Y. Shen and Mr. L. Zhang for their technical assistance. This study was supported in part by grants from the Nanjing Technology Development Project Fund (No. 200702075), the Medical Science and Technology Development Foundation, Nanjing Department of Health (No. YKK10175), and the BenQ Medical Center Research Fund (No. SRD20100001).

References

- 1.Stewart BW, Kleihues P, editors. World Cancer Report. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Geneva: 2003. pp. 232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehrotra R, Yadav S. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: etiology, pathogenesis and prognostic value of genomic alterations. Indian J Cancer. 2006;43:60–66. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.25886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor S, Wakem M, Dijkman G, Alsarraj M, Nguyen M. A practical approach to RT-qPCR-publishing data that conform to the MIQE guidelines. Methods. 2010;50:S1–S5. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay RT. SUMO-specific proteases: a twist in the tail. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu Y, Li J, Zuo Y, Deng J, Wang LS, Chen GQ. SUMO-specific protease 1 regulates the in vitro and in vivo growth of colon cancer cells with the upregulated expression of CDK inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 2011;309:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng J, Kang X, Zhang S, Yeh ET. SUMO-specific protease1 is essential for stabilization of HIF1a during hypoxia. Cell. 2007;131:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bawa-Khalfe T, Yeh ET. SUMO losing balance: SUMO proteases disrupt SUMO homeostasis to facilitate cancer development and progression. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:748–752. doi: 10.1177/1947601910382555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bawa-Khalfe T, Cheng J, Wang Z, Yeh ET. Induction of the SUMO-specific protease 1 transcription by the androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37341–37349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa M, Moritani S, Murakumo Y, Sato T, Hagiwara S, Suzuki C, Mii S, Jijiwa M, Enomoto A, Asai N, Ichihara S, Takahashi M. CD109 expression in basal-like breast carcinoma. Pathol Int. 2008;58:288–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagikura M, Murakumo Y, Hasegawa M, Jijiwa M, Hagiwara S, Mii S, Hagikura S, Matsukawa Y, Yoshino Y, Hattori R, Wakai K, Nakamura S, Gotoh M, Takahashi M. Correlation of pathological grade and tumor stage of urothelial carcinomas with CD109 expression. Pathol Int. 2010;60:735–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang JM, Hashimoto M, Kawai K, Murakumo Y, Sato T, Ichihara M, Nakamura S, Takahashi M. CD109 expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Pathol Int. 2005;55:165–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rother K, Dengl M, Lorenz J, Tschöp K, Kirschner R, Mössner J, Engeland K. Gene expression of cyclin-dependent kinase subunit Cks2 is repressed by the tumor suppressor p53 but not by the related proteins p63 or p73. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1166–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lan Y, Zhang Y, Wang J, Lin C, Ittmann MM, Wang F. Aberrant expression of Cks1 and Cks2 contributes to prostate tumorigenesis by promoting proliferation and inhibiting programmed cell death. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:543–551. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Lin YM, Hasegawa S, Shimokawa T, Murata K, Kameyama M, Ishikawa O, Katagiri T, Tsunoda T, Nakamura Y, Furukawa Y. Genes associated with liver metastasis of colon cancer, identified by genome-wide cDNA microarray. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uchikado Y, Inoue H, Haraguchi N, Mimori K, Natsugoe S, Okumura H, Aikou T, Mori M. Gene expression profiling of lymph node metastasis by oligomicroarray analysis using laser microdissection in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:1337–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kariya Y, Mori T, Yasuda C, Watanabe N, Kaneko Y, Nakashima Y, Ogawa T, Miyazaki K. Localization of laminin alpha3B chain in vascular and epithelial basement membranes of normal human tissues and its down-regulation in skin cancers. J Mol Histol. 2008;39:435–446. doi: 10.1007/s10735-008-9183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malan D, Reppel M, Dobrowolski R, Roell W, Smyth N, Hescheler J, Paulsson M, Bloch W, Fleischmann BK. Lack of laminin gamma1 in embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes causes inhomogeneous electrical spreading despite intact differentiation and function. Stem Cells. 2009;27:88–99. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuruta D, Kobayashi H, Imanishi H, Sugawara K, Ishii M, Jones JC. Laminin-332-integrin interaction: a target for cancer therapy? Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:1968–1975. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnaout MA, Goodman SL, Xiong JP. Structure and mechanics of integrin-based cell adhesion. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao-Yang Z, Ke-Sen X, Qing-Si H, Wei-Bo N, Jia-Yong W, Yue-Tang M, Jin-Shen W, Guo-Qiang W, Guang-Yun Y, Jun N. Signaling and regulatory mechanisms of integrin alphavbeta6 on the apoptosis of colon cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Tan H, Dong X, Xu Z, Shi C, Han X, Jiang H, Krissansen GW, Sun X. Antisense integrin alphaV and beta3 gene therapy suppresses subcutaneously implanted hepatocellular carcinomas. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proctor JM, Zang K, Wang D, Wang R, Reichardt LF. Vascular development of the brain requires beta8 integrin expression in the neuroepithelium. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9940–9948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]