Abstract

We report a case of trigeminal neuralgia caused by persistent trigeminal artery (PTA) associated with asymptomatic left temporal cavernoma. Our patient presented unstable blood hypertension and the pain of typical trigeminal neuralgia over the second and third divisions of the nerve in the right side of the face. The attacks were often precipitated during physical exertion. MRI and Angio-MRI revealed the persistent carotid basilar anastomosis and occasionally left parietal cavernoma. After drug treatment of blood hypertension, spontaneous recovery of neuralgia was observed and we planned surgical treatment of left temporal cavernoma.

Keywords: Persistent trigeminal artery, Trigeminal neuralgia, Cavernoma

Introduction

Persistent trigeminal artery (PTA) originates just before or at the point where internal carotid artery enters the cavernous sinus. As PTA leaves the carotid, it runs extradurally below the oculomotor and trochlear nerves and medial to ophthalmic branch of trigeminal nerve. Finally, PTA passes under petroclinoidal ligament or perforates the dura near the clivus to join the basilar artery between superior or anterior inferior cerebellar artery. Otherwise, the PTA can get in the posterior fossa either from Meckel’s cave or from an isolated dural foramen, directly supplying the cerebellum vascularization without anastomoses with the basilar artery [15]. These relationships may explain the reported cranial syndromes related to PTA persistence. Anatomical and angiographic studies suggested that trigeminal neuralgia and abducens nerve palsy might result from anomalous PTA [1, 10, 16]. We report a case of trigeminal neuralgia caused by PTA associated with asymptomatic left parietal cavernoma. After drug treatment of blood hypertension, we observed spontaneous recovery of trigeminal neuralgia suggesting that transient increase of the flow of the vessel carried out neuralgia.

Case report

A 56-year-old woman was admitted to the Department of Neurosurgery of Second University of Naples presenting typical trigeminal neuralgia over the second and third branches of the nerve in the right side. The neuralgia started during unstable blood hypertension and the attacks were precipitated during physical exertion. The neurological examination was normal. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and angio-MRI (MRA) showed a right PTA characterized by a moderate ectasia in its proximal tract and an occasionally left parietal cavernoma. From its origin, PTA was first positioned lower and then reached the basilar artery. The posterior communicating artery was not visible. PTA presented a lateral course, originating from the posterolateral aspect of the intracavernous portion of the internal carotid artery; it ran underneath the auditory nerve and continued caudally between the trigeminal nerve and abducens nerve to join the distal basilar artery. The course of the trigeminal nerve was obtained from volumetric sequence T2: the superior cerebellar artery was observed without conflict, while the PTA was adjacent to the right side of the trigeminal nerve. Moreover, an occasionally left parietal cavernoma was observed, presenting typical findings with a rim of gliosis with haemosiderin deposit surrounding it following previous bleeding (Figs. 1, 2).

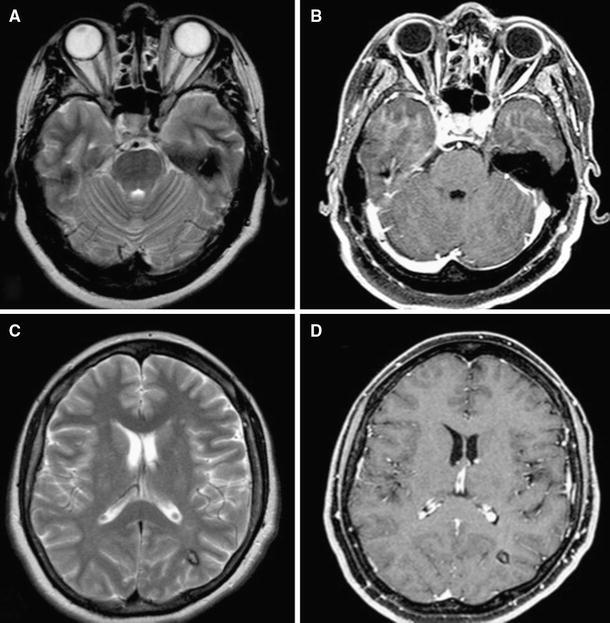

Fig. 1.

a MRI showed the course of the trigeminal nerve by sequence T2, PTA was adjacent to the trigeminal nerve, b on gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image, PTA presented lateral course, c on T2-weighted image, left parietal cavernoma with typical rim haemosiderin deposit, d on gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image, high-intensity mass of left parietal cavernoma

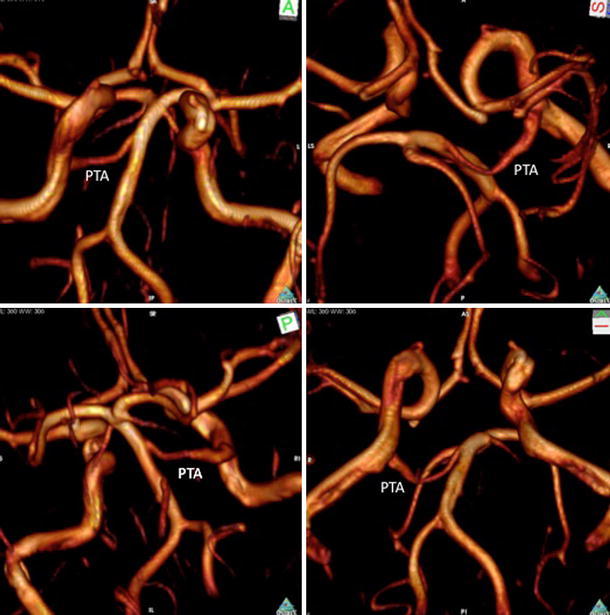

Fig. 2.

MRA showed PTA with lateral course, originating from the posterolateral aspect of the intracavernous portion of the internal carotid artery, it ran underneath the auditory nerve and continued caudally between the trigeminal nerve and abducens nerve to join the distal basilar artery

We considered short history of unstable blood hypertension; therefore, the patient was treated with calcium antagonist for about 1 week. After drug treatment of blood hypertension, spontaneous recovery of neuralgia was observed and we planned surgical treatment of the left parietal cavernoma. At 3 years of follow-up, she remains pain free.

Discussion

Embryologically, during the 4-mm embryo stage, the carotid arteries via four important arterial anastomoses supply the paired longitudinal neural arteries: the trigeminal artery, the otic artery, the hypoglossal artery and the proatlantal intersegmental artery. During the 5–6-mm embryo stage, an anastomosis forms between the distal internal carotid artery and the corresponding longitudinal neural artery, which becomes the posterior communicating artery. Subsequently, the presegmental arteries and proatlantal intersegmental arteries regress and obliterate. If there is incomplete regression, or if the ipsilateral posterior communicating artery does not develop properly, a persisting caroticobasilar anastomosis, such as the PTA, may result [4]. The incidence of a PTA was reported to be between 0.1 and 0.6% and Uchino reported a PTA on MR angiography using the three-dimensional time of flight (3D-TOF) technique at a rate of 0.76% in a series of 523 patients screened for cerebrovascular disease [14]. In 1969, Kempe described three different carotid basilar anastomoses. These were persistent primitive trigeminal, persistent primitive acoustic, and persistent primitive hypoglossal arteries. All three patients gave a history of cranial nerve root irritation consisting respectively of tic douloureux, hemifacial spasm with neuralgia of the nerve of Wrisberg, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia [6]. Other authors described a case of PTA which was a large vessel in close proximity to the trigeminal nerve as it curves around the petrous bone into Meckel’s cave. It can also be dilated and this can result in a more severe compression of the trigeminal nerve. Therefore, they affirmed that in patients with a PTA, neurovascular compression even outside the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve can result in the clinical features of trigeminal neuralgia. The prevalence of a PTA in patients presenting with trigeminal neuralgia was 2.2%. They concluded that with respect to the clinical significance, a PTA has to be considered in trigeminal neuralgia and diagnosis can easily be made in a non-invasive way using MRI/MRA [4]. Chidambaranathan affirmed that MRI showed the origin of PTA to be arising from the postero-lateral aspect of the posterior bend of cavernous segment of right internal carotid artery; it coursed postero-laterally and inferiorly around the dorsum sellae and communicated with basilar artery in the prepontine cistern. In its lateral course, it compressed and distorted the root entry zone of right trigeminal nerve [2]. The PTA can take a lateral or medial course. When originating from the posterolateral aspect of the intracavernous portion of the internal carotid artery, it runs underneath the auditory nerve and continues caudally between the trigeminal nerve and abducens nerve to join the distal basilar artery. When it arises from the posteromedial aspect of the intracavernous portion of the internal carotid artery, it runs caudally through the sella turcica, and pierces the clival dura at the dorsum sellae to join the basilar artery. Although cranial nerve dysfunction is less likely to occur in the second variant, its significance is crucial in planning transsphenoidal surgery [5].

We reported a case of PTA with lateral course in a patient with unstable blood hypertension and trigeminal neuralgia associated with a left parietal cavernoma. As Sindou and Pollock [9, 12], we considered that, although no procedure is best for patients affected by trigeminal neuralgia, posterior fossa exploration is associated with better facial pain outcomes. In this case, our therapeutic strategy must consider the cavernoma and the neurovascular conflict; during drug treatment of blood hypertension, spontaneous recovery of neuralgia was observed. Spontaneous recovery of cranial disorder due to the vascular compression has occasionally been encountered. In such cases, cranial nerve dysfunction could be caused by the transient increase in the flow of the vessel [1]. In our patient, history of unstable hypertension may favor this hypothesis.

We observed occasionally left temporal cavernoma which was supratentorial and asymptomatic. However, Talanovet described a 16-year-old boy with arteriovenous malformation (AVM) of septum pellucidum in combination with left side PTA, emphasizing the interest for two reasons. The first is the possibility of increased pressure in the afferent arteries of AVM. It was illustrated by distinctive displacement of the zones of the hemodynamical balance around the circle of Willis. The raised pressure in conditions of shunting can be explained using principles of the constant shear stress in the vascular system. The second is the features of venous system that may be causative for PTA. These features included the presence of the large anastomotic vein between petrosal and cavernous sinuses, enlargement of petrosal sinuses and shrinking of transverse sinus ipsilateral to PTA [13]. Ohatakara described one case of trigeminal neuralgia in patient with AVM and analyzed 23 cases reported in literature; he affirmed that embryonic maldevelopment might have resulted in these independently uncommon conditions and that the course of PTA was medial and distant from the trigeminal nerve based on 3D-CT angiography. The neuralgia was probably due to direct damage of hematoma [8]. Cloft affirmed that there is no increased prevalence of intracranial aneurysms in patients with PTA [3]. Other authors reported PTA aneurism with cerebellar hemangioblastoma and affirmed that simple coincidence might account for this case [7]. A rare case of trigeminal neuralgia caused by tentorial meningioma associated with PTA was reported. A left cerebello-pontine angle meningioma was found associated with a right PTA connecting the proximal portion of the cavernous internal carotid artery with the basilar artery, supplying the bilateral superior cerebellar arteries; the tumor was totally removed via the suboccipital approach, relieving the pain completely [11].

To our knowledge, this is first reported case in the literature of trigeminal neuralgia caused by PTA associated with asymptomatic left temporal cavernoma.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Bosco D, Consoli D, Lanza PL, Plastino M, Nicoletti F, Ceccotti C. Complete oculomotor palsy caused by persistent trigeminal artery. Neurol Sci. 2010;31:657–659. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chidambaranathan N, Sayeed ZA, Sunder K, Meera K. Persistent trigeminal artery: a rare cause of trigeminal neuralgia—MR imaging. Neurol India. 2006;54:226–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cloft HJ, Razack N, Kallmes DF. Prevalence of cerebral aneurysms in patients with persistent primitive trigeminal artery. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:865–867. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.5.0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bondt BJ, Stokroos R, Casselman J. Persistent trigeminal artery associated with trigeminal neuralgia: hypothesis of neurovascular compression. Neuroradiology. 2007;49:23–26. doi: 10.1007/s00234-006-0150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalidindi RS, Balen F, Hassan A, Al-Din A. Persistent trigeminal artery presenting as intermittent isolated sixth nerve palsy. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:515–519. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kempe LG, Smith DR. Trigeminal neuralgia, facial spasm, intermedius and glossopharyngeal neuralgia with persistent carotid basilar anastomosis. J Neurosurg. 1969;31:445–451. doi: 10.3171/jns.1969.31.4.0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murai Y, Kobayashi S, Tateyama K, Teramoto A. Persistent primitive trigeminal artery aneurysm associated with cerebellar hemangioblastoma. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2006;46:143–146. doi: 10.2176/nmc.46.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohtakara K, Kuga Y, Murao K, Kojima T, Taki W, Waga S. Posterior fossa arteriovenous malformation associated with persistent primitive trigeminal artery—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2000;40:169–172. doi: 10.2176/nmc.40.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollock BE, Stein KJ. Surgical management of trigeminal neuralgia patients with recurrent or persistent pain despite three or more prior operations. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poyatos C. Persistent trigeminal artery and isolated sixth cranial nerve. Rev Neurol. 2007;45:128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato M, Kondo A, Otsuka S, Tanabe H, Matsuura N, Hasegawa K, Chin M, Saiki M. Trigeminal neuralgia: association with tentorial meningioma and persistent primitive trigeminal artery. Fukushima J Med Sci. 1995;41:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sindou M. Trigeminal neuralgia: a plea for microvascular decompression as the first surgical option. Anatomy should prevail. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010;152:361–364. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0506-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talanov AB, Filatov Iu M, Eliava S, Novikov AE, Kulishova Ia G (2009) [Arteriovenous malformation of septum pellucidum in combination with persistent trigeminal neuralgia]. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko 50–53 (discusion 53–54) [PubMed]

- 14.Uchino A, Kato A, Takase Y, Kudo S. Persistent trigeminal artery variants detected by MR angiography. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1801–1804. doi: 10.1007/s003300000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uchino A, Sawada A, Takase Y, Kudo S. MR angiography of anomalous branches of the internal carotid artery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1409–1414. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.5.1811409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamada Y, Kondo A, Tanabe H. Trigeminal neuralgia associated with an anomalous artery originating from the persistent primitive trigeminal artery. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2006;46:194–197. doi: 10.2176/nmc.46.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]