Abstract

We present here a 25-year-old woman with genetically confirmed (p.R276L mutation in the GFAP gene) juvenile-onset AxD. Episodic vomiting appeared at age nine, causing anorexia and insufficient growth. Brain MRI at age 11 showed a small nodular lesion with contrast enhancement in the left dorsal portion of the cervicomedullary junction. Her episodic vomiting improved spontaneously at age 13, and she became neurologically asymptomatic. The enhancement of the lesion disappeared simultaneously, although the plaque remained. Longitudinal MRI observations, however, revealed insidiously progressive cervicomedullary atrophy without a signal change. This case broadens our knowledge of AxD: (1) molecular analysis of the GFAP gene is warranted in patients with MRI evidence of tumor-like lesions in the brainstem, particularly if they present with isolated episodic vomiting and/or anorexia; (2) the disease can be self-remitting for at least 12 years; (3) cervicomedullary atrophy, characteristic of the adult form, can be insidiously progressive without a signal change before the clinical symptoms appear.

Keywords: Alexander disease, GFAP, Vomiting, Anorexia nervosa, Remission, Cervicomedullary atrophy

Introduction

Typical Alexander disease (AxD) (OMIM #203450) is a lethal infantile leukoencephalopathy with frontal predominance characterized by Rosenthal fiber deposition in astrocytes (reviewed in [1]). The discovery that mutations in the gene coding glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) are responsible for AxD has led to the identification of both juvenile (age at onset: 2–12 years) and adult (age at onset: over 12 years) forms of the disease. Each subtype is characterized by specific MRI findings: in the juvenile form, tumor-like nodular and/or swollen lesions in the brainstem [2, 3]; in the adult form, a distinctive tadpole-like brainstem atrophy, consisting of severe atrophy of the medulla oblongata and cervical spinal cord, with an intact pontine base [4, 5]. The reason for the age-related variability of the lesions in AxD remains unclear.

We present here a novel case of genetically confirmed AxD. The patient’s episodic vomiting improved spontaneously and she became neurologically asymptomatic, although longitudinal observations for more than 12 years revealed insidiously progressive cervicomedullary atrophy.

Case report

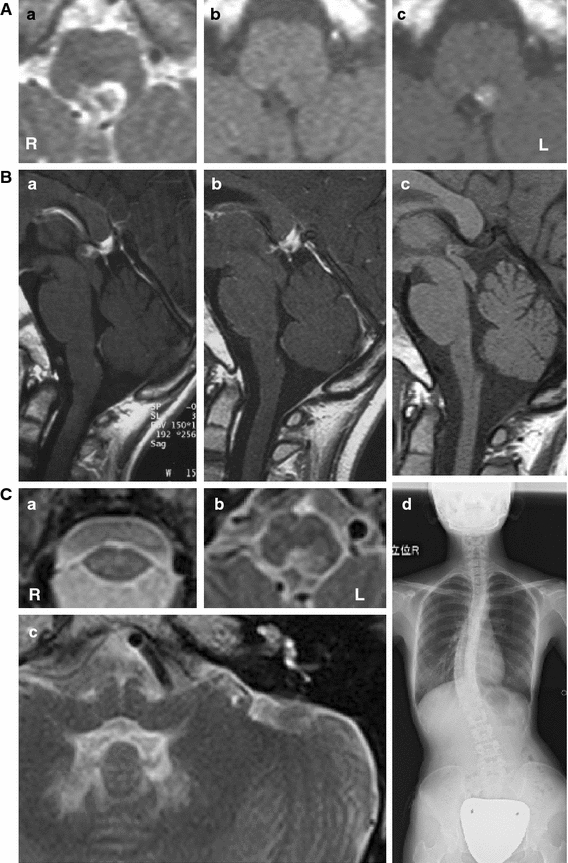

The patient, a 25-year-old Japanese woman, the second child of non-consanguineous healthy parents, was born after 39 weeks of gestation with no prenatal or perinatal problems. Her early developmental milestones were normal, except for two episodes of febrile seizures at 1 year of age, which never recurred. From the age of three, her food intake was relatively small, and malnutrition delayed her physical growth, but her mental development was normal. From the age of nine, she suffered from episodic vomiting after eating, which caused anorexia. At the age of 11, she was referred to our hospital for further investigation of progressive weight loss (−1.4 kg/year). Her height was 123 cm (−3.0 SD) and she weighed 18.6 kg (−2.5 SD). She had normal intelligence and no neurological deficits, except for episodic postprandial vomiting. Detailed physical investigations showed no significant abnormalities, except for scoliosis. Gastrointestinal, metabolic, endocrinological and psychological disorders were ruled out. No neurophysiological examinations were performed, although, brain MRI revealed a 7-mm-sized lesion in the posterior dorsal portion of the cervicomedullary junction, which was enhanced with Gd-DTPA (Fig. 1A). Signal changes were also detected bilaterally in the dentate nuclei without enhancement. No other signal abnormalities were noted. During follow-up on MRIs, taken twice a year, the enhancement of the lesion disappeared after 2 years, although the plaque remained. Her episodic vomiting also vanished almost simultaneously. Her growth stopped at the age of 17. At age 25, she is frail 140 cm/33.4 kg with scoliosis. She has normal intelligence and is asymptomatic. A tiny plaque without enhancement, the same size as before, is still visible in the dorsal part of medulla oblongata (Fig. 1C), although cervicomedullary atrophy without a signal change has advanced (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Serial radiological studies. A First MRI of the medulla oblongata (at age 11): axial T2-weighted image (T2-WI) (a), T1-WI (b), and T1-WI with gadolinium enhancement (c) of axial sections. The lesion is 7 mm in size, hyper-intense, but hypo-intense inside on T2-WI (a), iso- to hypo-intense on T1-WI (b), with contrast enhancement (c). Except for the bilateral hilus of the dentate nucleus (same as 14 years later; C-c), no other signal abnormalities were noted (data not shown). The enhancement disappeared 2 years later (data not shown), although, the plaque remains. B Chronological sagittal section of the brainstem MRI at age 11 (a), 16 (b) and 25 (c). Brainstem atrophy is unremarkable at age 11 (a), although, with time, progressive atrophy of medulla oblongata is seen (b, c). The anterior–posterior diameter at the middle of the medulla oblongata was 11.7 mm at age 11 (a), but only 8.8 mm at age 25 (c). C Radiological study at age 25. Axial T2-WI (a–c). Moderate atrophy of cervical spinal cord (a) and medulla (b) are seen. A small plaque in the dorsal part of medulla oblongata (b) without contrast enhancement (data not shown) remains, although its size has not changed since age 11 (A-a). The hilus of the dentate nucleus is hyper-intense bilaterally without enhancement (data not shown), although, no other signal change is detected in the brainstem (c). No pontine or midbrain atrophy, abnormalities in the basal ganglia, “ventricular garlands” or leukodystrophy in deep white matter were observed (data not shown). Mild scoliosis was also observed in this patient (d)

Sequencing of the GFAP gene with informed consent revealed a heterozygous missense mutation in exon 5 (c.827G>T), causing a change of arginine to leucine at amino acid position 276 (p.R276L). The mutation was not found in her mother. The father, who died in traffic accident in his forties, could not be investigated. This mutation has already been described as responsible for pathologically proven hereditary [4] and sporadic [5] cases of adult-onset AxD. According to an interview, there was no relationship between the present patient and the families previously reported, although they originated from the same region of Japan.

Discussion

We present a Japanese patient with genetically confirmed juvenile-onset AxD. Episodic vomiting, which was the only sign of bulbar dysfunction, caused malnutrition and weight loss, probably related to a tiny lesion seen by MRI in dorsal part of medulla oblongata, presumably involving the “area postrema”, which plays an essential role in the system controlling feeding [6]. Similar cases have already been reported [7, 8], but the patients in the literature also had additional bulbar symptoms, such as dysphagia and dysphonia. This case indicates that a molecular analysis of the GFAP gene is warranted in patients with MRI evidence of even tiny tumor-like lesions in the brainstem, particularly if they present with isolated episodic vomiting and/or anorexia.

It is noteworthy that the bulbar symptom of this patient regressed spontaneously. She is now 25 years old, and is absolutely free of neurological symptoms, except for short stature with scoliosis, presumably a sign of AxD [9]. This case suggests that the symptoms of AxD can be self-remitting, unlike those of other neurodegenerative disorders, and that the prognosis might not necessarily be unfavorable. To our knowledge, no other AxD patient whose symptoms vanished for such a long period of time has been reported in the literature. Very recently, a case of adult-onset AxD with remission and relapse was reported, but the remission was only partial and lasted less than 5 years [10]; atypical AxD has been mistaken for remitting–relapsing multiple sclerosis [1]. Because the cervicomedullary atrophy continues to progress in our patient (Fig. 1B), she might still develop an adult form of the disease in the future.

The longitudinal observation of progressive cervicomedullary atrophy, which is characteristic of the adult AxD [4, 5], is interesting. It has been speculated that brainstem atrophy in the adult form of AxD might result from tissue damage related to the contrast enhanced nodular and/or swollen lesions usually observed in the juvenile form of the disease. A recent report of a patient with progressive medullary atrophy has reinforced this hypothesis [11]. The 20-year-old patient had an expanded cervicomedullary lesion with patchy contrast enhancement; progressive atrophy was observed 5.5 years later [11].

Our case differs, however, in that the medullary lesion was confined to a tiny portion of the dorsal region, and seems too small to be responsible for expansion of the cervicomedullary lesion, suggesting that the latter, which is reminiscent of chronic progressive neuro-Behçet’s disease, results from a different pathological process. [12]. In neuro-Behçet’s disease, subacute brainstem encephalitis, which is the most common in parenchymal involvement, shows hypertense T2 lesion with contrast enhancement. Spontaneous self-remission without therapy has been reported, although, some patients develop a slowly progressive disease with insidiously advancing brainstem atrophy [12].

Observation of our patient for over 14 years, allowed us to demonstrate, for the first time, that the marked cervicomedullary atrophy characteristic of adult-onset AxD might result from an insidiously progressive process. More patients will be needed to determine whether a nodular lesion with contrast enhancement, however small, is essential to trigger the cervicomedullary atrophy or whether the mutation in the GFAP gene is sufficient.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Alexander disease research grants from the Intractable Disease Research Grants, from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of the government of Japan. We are very grateful to Dr. Merle Ruberg for critical reading of this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Brenner M, Goldman JE, Quinlan RA, Messing A. Alexander disease: a genetic disorder of astrocytes, chap 24. In: Parpura V, Haydon PG, editors. Astrocytes in (patho)physiology of the nervous system. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 591–647. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Knaap MS, Salomons GS, Li R, Franzoni E, Gutiérrez-Solana LG, Smit LME, Robinson R, Ferrie CD, Cree B, Reddy A, Thomas N, Banwell B, Barkhof F, Jakobs C, Johnson A, Messing A, Brenner M. Unusual variants of Alexander’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:327–338. doi: 10.1002/ana.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Knaap MS, Ramesh V, Schiffmann R, Blaser S, Kyllerman M, Gholkar A, Ellison DW, van der Voorn JP, van Dooren SJM, Jakobs C, Barkhof F, Salomons GS. Alexander disease. Ventricular garlands and abnormalities of the medulla and spinal cord. Neurology. 2006;66:494–498. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000198770.80743.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namekawa M, Takiyama Y, Aoki Y, Takayashiki N, Sakoe K, Shimazaki H, Taguchi T, Tanaka Y, Nishizawa M, Saito K, Matsubara Y, Nakano I. Identification of GFAP gene mutation in hereditary adult-onset Alexander’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:779–785. doi: 10.1002/ana.10375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Namekawa M, Takiyama Y, Honda J, Shimazaki H, Sakoe K, Nakano I (2010) Adult-onset Alexander disease with typical “tadpole” brainstem atrophy and unusual bilateral basal ganglia involvement: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Neurology10:21. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-10-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Price CJ, Hoyda TD, Ferguson AV. The area postrema: a brain monitor and integrator of systemic autonomic state. Neuroscientist. 2008;14:182–194. doi: 10.1177/1073858407311100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franzoni E, van der Knaap MS, Errani A, Colonnelli MC, Bracceschi R, Malaspina E, Moscano FC, Garone C, Sarajlija J, Zimmerman RA, Salomons GS, Bernardi B. Unusual diagnosis in a child suffering from juvenile Alexander disease: clinical and imaging report. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:1075–1080. doi: 10.1177/7010.2006.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niinikoski H, Haataja L, Brander A, Valanne L, Blaser S. Alexander disease as a cause of nocturnal vomiting in a 7-year-old girl. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:872–875. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozturk C, Tezer M, Karatoprak O, Hamzaoglu A. A rare cause of neuromuscular scoliosis: Alexander disease. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76:195–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayaki T, Shinohara M, Tatsumi S, Namekawa M, Yamamoto T. A case of sporadic adult Alexander disease presenting with acute onset, remission and relapse. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:1292–1293. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.178079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romano S, Salvetti M, Ceccherini I, De Simone T, Savoiardo M. Brainstem signs with progressing atrophy of medulla oblongata and upper cervical spinal cord. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:562–570. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Araji A, Kidd DP. Neuro-Behçet’s disease: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:192–204. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]