Abstract

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare disease characterized by progressive inflammation and destruction of cartilaginous structures such as ears, nose, and tracheolaryngeal structures. As a result, tracheolaryngeal involvement makes anesthetic management a challenge. Anesthetic management of a patient with relapsing polychondritis may encounter airway problems caused by severe tracheal stenosis. We present the case of a 60-year-old woman with relapsing polychondritis who underwent wedge resection of the stomach under epidural analgesia. Thoracic epidural blockade of the T4-10 dermatome was achieved by epidural injection of 7 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine and 50 µg of fentanyl. The patient was tolerable during the operation. We suggest that epidural analgesia may be an alternative to general anesthesia for patients with relapsing polychondritis undergoing upper abdominal surgery.

Keywords: Epidural analgesia, Relapsing polychondritis

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare disorder of uncertain etiology. It is characterized by recurrent inflammation and progressive destruction of cartilaginous structures [1,2]. Ears, nose, and tracheolaryngeal support structures are frequently involved. Recurrent inflammation of the tracheobronchial structure can lead to airway stricture and deformity, by which respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea and orthopnea may occur. Due to these problems, the appropriate airway management thereof is a significant challenge to anesthesiologists. We present a recent case and discuss the anesthetic management of a patient with relapsing polychondritis.

Case Report

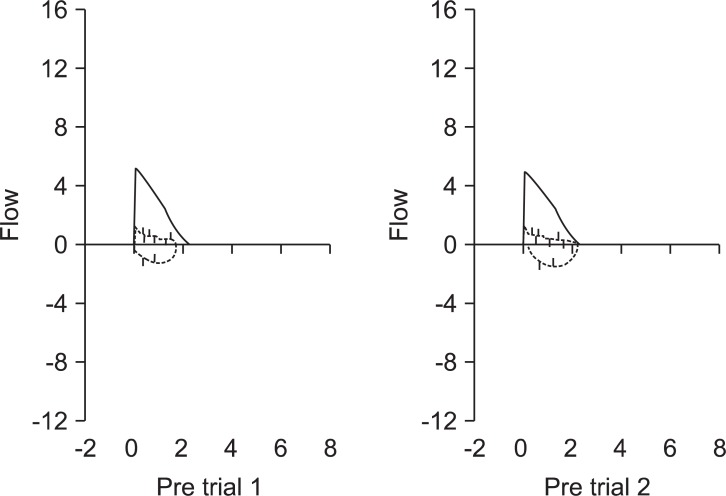

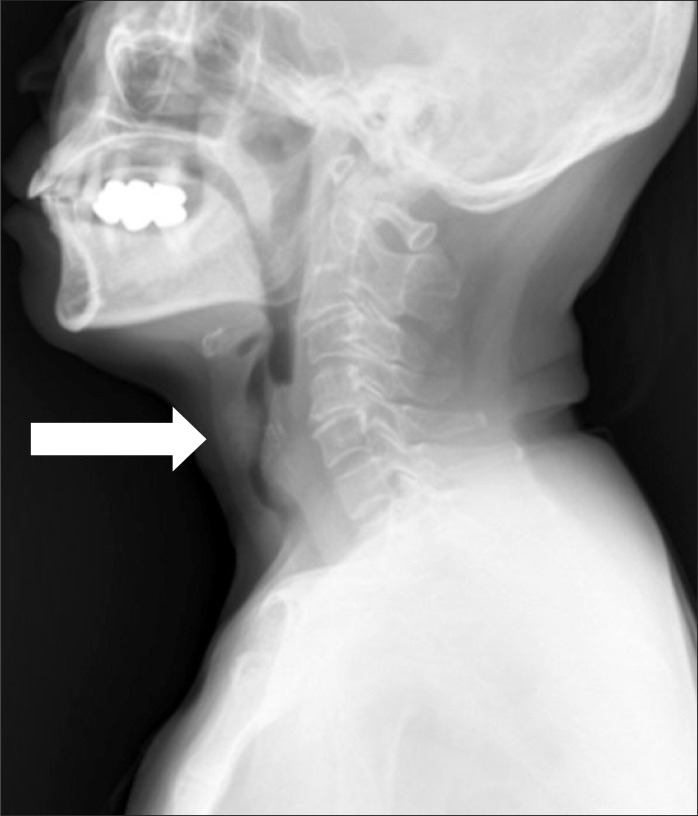

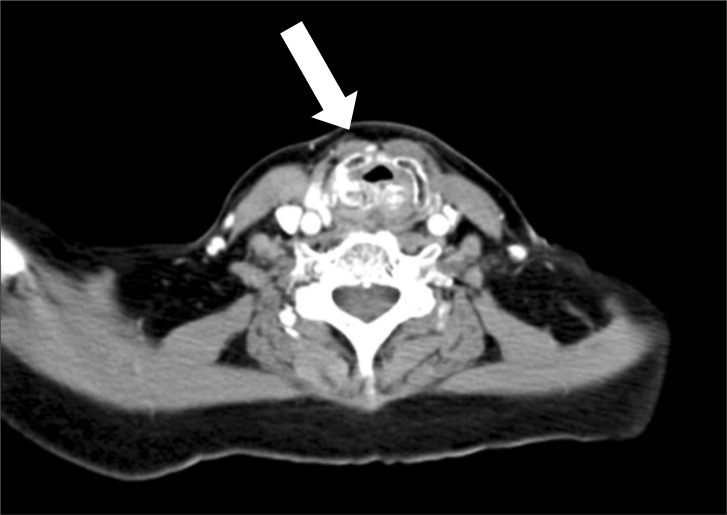

A 60-year-old Asian woman, weighing 48 kg with a height of 147 cm, was scheduled for laparoscopic wedge resection of the stomach due to a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). She had suffered from relapsing polychondritis for fifteen years and had been controlled with steroid therapy. She had hoarseness for fourteen years. Recently she presented aggravated dyspnea on exertion and had difficulty lying on her back because of orthopnea for a few of months. Forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and FEV1/FVC were 2.23 L (94% of predicted), 0.69 L (40% of predicted), and 31%, respectively. Her flow-volume loop showed severe airway obstruction (Fig. 1). A radiographic lateral view of the neck showed subglottic tracheal stenosis (Fig. 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck also showed narrowing of the trachea at C5-6 level (approximately 5.75 mm in maximal diameter) (Fig. 3). An arterial blood gas test showed a pH 7.41, PaCO2 37 mmHg, PaO2 69 mmHg, SaO2 94%, and HCO3- 24 mEq/L in room air. Other laboratory findings were in the normal range.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative pulmonary function test shows severe obstructive respiratory pattern.

Fig. 2.

Radiographic lateral view of the neck shows remarkable tracheal stenosis (6 mm in narrowest diameter).

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography (CT) demonstrates expansion with fragmentation of laryngeal cartilages and diffuse wall thickening with narrowing of trachea (approximately 5.75 mm in narrowest diameter).

Owing to potential risks of airway compromise during intubation and/or extubation of an endotracheal tube under general anesthesia, the operation was converted from a laparoscopic surgery to an open laparotomy under epidural analgesia one day before operation. Without premedication, the patient was reassured with sufficient explanation on the procedures and anesthetic technique. In the operating room, non-invasive blood pressure, electrocardiography, and pulse oxymetry were monitored. After placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, an 18 gauge Tuohy epidural needle was inserted between the seventh and eighth thoracic vertebrae. The epidural space was identified by the loss of the resistance technique. An epidural catheter was inserted in the epidural space through a needle and advanced 5 cm toward the cephalic direction. After a test dose injection of 3 ml of 2% lidocaine containing 1 : 200,000 epinephrine, neither an increase in heart rate nor adverse symptoms of spinal anesthesia were detected. After a catheter was fixed, 7 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine and 50 µg of fentanyl was injected. The level of sensory block was tested by pin-prick every five minutes. The sensory block of the T4-10 level was achieved in fifteen minutes. She was comfortable and did not complain of pain in the upper abdomen when the surgeon performed a midline skin incision above the umbilicus. Intraoperative vital signs were relatively stable with a blood pressure of 105-120/60-75 mmHg and a heart rate of 70-80 beats/min. During the operation, the stomach was pulled taut to resect the tumor because a mass was located at the posterior wall of the fundus. As the surgeon pulled on the stomach, she complained of nausea and discomfort. Being so, we infused remifentanil at 0.03-0.06 µg/kg/min and SpO2 slowly decreased to 95% from 98%. After applying a face mask at 5 L/min, SpO2 was maintained at 96-97% throughout the rest of the operation. After the operation, the patient was transferred to the post-anesthetic care unit and her vital signs including saturation were within acceptable ranges in room air. The rest of the postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was discharged on the sixth day after the operation without any airway complications.

Discussion

Relapsing polychondritis is a disorder that has a variety of clinical manifestations and is considered an autoimmune disease resulting in cartilage breakdown [2]. The disorder is usually presented with episodes of erythema, pain, and swelling of the ears, nose, and joints. Symptomatic tracheobronchial involvement implies a poor prognosis. Laryngotracheal symptoms are present in approximately 25% of the patients in the initial course of the disease, however, airway symptoms eventually occur in 50% of all patients with relapsing polychondritis [3]. The disorder causes airway obstruction by two mechanisms. The first is a stricture due to inflammatory swelling or scar formation in the glottic and subglottic areas. The second is dynamic airway collapse during respiration due to destruction of tracheal cartilage [4]. Accordingly, radiographic and bronchoscopic examinations may provide incorrect information for determining the degree of tracheal obstruction, as dynamic airway collapse occurs during respiration. However, inspiratory and expiratory flow-volume loops are useful in predicting the functional degree of intrathoracic and extrathoracic obstruction [5]. In this case, the patient demonstrated severe airway obstruction on flow-volume loop that was well-correlated with her severe respiratory symptoms, including orthopnea.

The most common causes of death among patients with relapsing polychondritis are infection, airway compromise, and cardiac complications [1,2]. Deaths from infection are frequently associated with laryngotracheal disease and pneumonia as well as corticosteroid therapy. Cardiovascular involvement, such as valvular disorders, aneurysmal dilatation of the great vessels and systemic vasculitis has been reported with relapsing polychondritis. Unfortunately, valve replacement surgery does not offer good prognosis because of the progression of underlying connective tissue degeneration [5]. There are a number of treatments available for relapsing polychondritis. Immunosuppression including steroid medication and chemotherapy with drugs is considered the primary option. Physiotherapy has a favorable effect on mucociliary clearance and may be useful for conditioning patients before elective surgical interventions. A tracheostomy or surgical interventions, such as airway stenting, are indicated for patients with aggravated tracheobronchial symptoms. Airway stenting leads to considerable improvement in airflow, particularly during expiration if the collapsing segment can be broadened by a stent [6].

The anesthetic management of patients with relapsing polychondritis is challenging due to airway compromise, which is also one of the most causes of death in this disease. During induction of anesthesia, airway compromise may be induced by collapse of supporting airway structures. Furthermore, after extubation, the potential for laryngeal obstruction may increase due to swelling, edema, and tissue injury of tracheal cartilage. Tanaka et al. [7] reported a case of relapsing polychondritis that underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy under general anesthesia. The patient was intubated with a 5.5 mm internal diameter endotracheal tube smoothly. After extubation, the patient showed no respiratory complications and was discharged a few days later. However, there was a distinct difference in the severity of disease between this case and Tanaka's case, as the patient in Tanaka's case had only mild dyspnea on exertion and no tracheal stenosis on the CT scan. The patient in this report, in contrast, suffered from orthopnea for a few months and a CT scan revealed narrowing of the subglottic area of which the diameter was approximately 5.75 mm. Flow-volume loop also corresponded to a severe obstructive pattern. In this case, we had to consider the possibility of failure of intubation and/or extubation of the endotracheal tube due to airway compromise. Even if intubation was able to be done, the risks of respiratory failure and reintubation after extubation were also high. Due to the risk of glottal or subglottal mucosal swelling induced by endotracheal intubation, local and regional anesthesia may be considered safer for patients with relapsing polychondritis than general anesthesia. However, local anesthesia does not always prevent airway problems [8]. Therefore, the possible side effects of endotracheal intubation should be weighed against its advantages and the expected procedure. In this case, the operation was converted from a laparoscopic surgery to an open laparotomy and was performed under epidural anesthesia after discussion with surgeon.

Continuous epidural analgesia has been suggested to have many benefits over conventional general anesthesia. These have included a reduction in neurohormonal response to surgical stimuli, preservation of spontaneous breathing and airway reflexes, decreased blood loss and postoperative pain, a reduced risk of thromboembolism, and a more rapid recovery of gastrointestinal motility [9]. Many studies have evaluated the usefulness of continuous epidural analgesia as the predominant anesthetic technique in abdominal surgery [10-12]. Other studies demonstrated that the postoperative deterioration of respiratory function and pulmonary complications decreased with thoracic epidural analgesia compared to general anaesthesia in abdominal or breast surgery [13,14]. In this case, thoracic epidural blockade provided appropriate analgesia. The patient felt sensations of nausea, discomfort or pain only when surgeons pulled on the mesentery or palpated the diaphragmatic surfaces of intraabdominal organs. This could be avoided with intravenous sedatives such as midazolam [15]. Instead, we infused remifentanil at a low rate instead of a sedative bolus in order to avoid respiratory depression and this was effective in reducing discomfort and pain.

Awareness of relapsing polychondritis, as a rare disorder, is significantly critical to conventional general anesthesia because dynamic airway collapse can occur. We were able to put a patient with severe relapsing polychondritis for wedge resection of stomach under thoracic epidural analgesia and found no specific complications as a result thereof. Thus, we present that thoracic epidural analgesia can be safely utilized as an anesthetic technique for patients undergoing upper abdominal surgery with airway difficulties, reduced pulmonary function, or weak respiratory muscles due to neuromuscular disease.

References

- 1.McAdam LP, O'Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976;55:193–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michet CJ, Jr, McKenna CH, Luthra HS, O'Fallon WM. Relapsing polychondritis. Survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:74–78. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-1-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayward AW, al-Shaikh B. Relapsing polychondritis and the anaesthetist. Anaesthesia. 1988;43:573–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1988.tb06692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krell WS, Staats BA, Hyatt RE. Pulmonary function in relapsing polychondritis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133:1120–1123. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.6.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgess FW, Whitlock W, Davis MJ, Patane PS. Anesthetic implications of relapsing polychondritis: a case report. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:570–572. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199009000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzmaurice BG, Brodsky JB, Kee ST, Foppiano LE, McNutt J. Anesthetic management of a patient with relapsing polychondritis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1999;13:309–311. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(99)90269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka TT, Furutani HF, Harioka TH. Anaesthetic management of a patient with relapsing polychondritis undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34:372–374. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0603400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biro P, Rohling R, Schmid S, Matter C, Lang M. Anesthesia in a patient with acute respiratory insufficiency due to relapsing polychondritis. J Clin Anesth. 1994;6:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(94)90121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norlander O. Combined epidural and general anesthesia for abdominal operations--a good technique. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 1988;39:203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blomberg S, Emanuelsson H, Kvist H, Lamm C, Pontén J, Waagstein F, et al. Effects of thoracic epidural anesthesia on coronary arteries and arterioles in patients with coronary artery disease. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:840–847. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeager MP, Glass DD, Neff RK, Brinck-Johnsen T. Epidural anesthesia and analgesia in high-risk surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 1987;66:729–736. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198706000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parthasarathy S, Ravishankar M, Aravindan U. Total radical gastrectomy under continuous thoracic epidural anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:358–359. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.68385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendolin H, Lahtinen J, Länsimies E, Tuppurainen T, Partanen K. The effect of thoracic epidural analgesia on respiratory function after cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1987;31:645–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1987.tb02637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groeben H, Schäfer B, Pavlakovic G, Silvanus MT, Peters J. Lung function under high thoracic segmental epidural anesthesia with ropivacaine or bupivacaine in patients with severe obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing breast surgery. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:536–541. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koltun WA, McKenna KJ, Rung G. Awake epidural anesthesia is effective and safe in the high-risk colectomy patient. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:1236–1241. doi: 10.1007/BF02257788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]