Abstract

The G-protein coupled receptor family of glutamate receptors, termed metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), are implicated in numerous cellular mechanisms ranging from neural development to the processing of cognitive, sensory, and motor information. Over the last decade, multiple mGluR-related signal cascades have been identified at excitatory synapses, indicating their potential roles in various forms of synaptic function and dysfunction. This review highlights recent studies investigating mGluR5, a subtype of group I mGluRs, and its association with a number of developmental, psychiatric, and senile synaptic disorders with respect to associated synaptic proteins, with an emphasis on translational pre-clinical studies targeting mGluR5 in a range of synaptic diseases of the brain.

Keywords: mGluR5, scaffolding proteins, synaptic disease

Introduction

The metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), a sub-family of glutamate receptors, are G-protein coupled and share a common molecular morphology with other G-protein-linked receptors. Expression is widespread throughout the mammalian nervous system, including the cerebral cortex (Lopez-Bendito et al., 2002), cerebellar neurons (Berthele et al., 1999), striatal neurons, and the spinal cord (Aronica et al., 2001). Functionally, mGluRs have been implicated as essential mediators of neural development (Zirpel et al., 2000; Di Giorgi Gerevini et al., 2004; Di Giorgi-Gerevini et al., 2005; Jo et al., 2006; Castiglione et al., 2008) and more broadly as important regulators of synaptic strength in the adult brain (Jong et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2012).

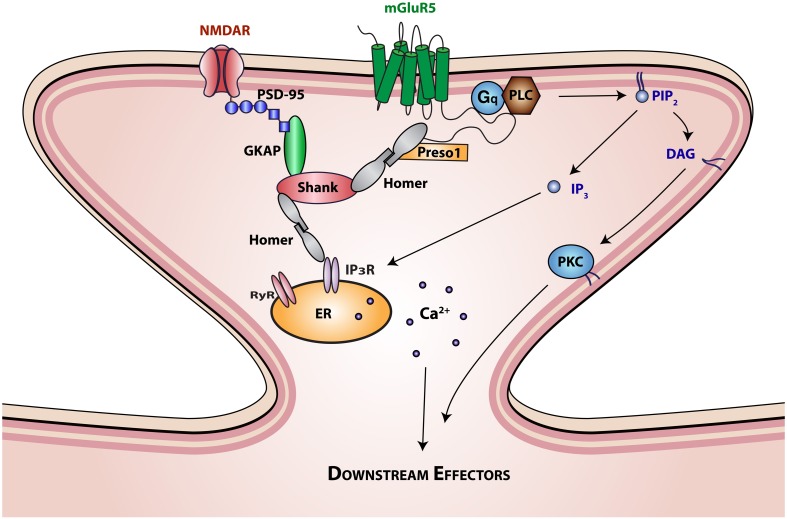

Metabotropic glutamate receptors can be subdivided into group I (mGluR 1 and 5), group II (mGluR 2 and 3), and group III (mGluR 4, 6, 7, and 8), according to G-protein coupling and mode of signal transduction. Group I receptors, which are expressed in the periphery of the postsynaptic densities of asymmetrical synapses, activate Gq/G11-phospholipase C mediated signaling via inositol phosphate hydrolysis and second messenger production (Figure 1; Berridge and Irvine, 1984). These second messengers are capable of initiating a myriad of cellular responses through their effects on intracellular Ca2+ stores and key enzymes, such as protein kinase C (Berridge and Irvine, 1984). In contrast to group I mGluRs, group II, and III mGluRs are distributed presynaptically. These receptors modulate cAMP signaling via the Gi/Go intracellular pathway (Anwyl, 1992; Shigemoto et al., 1997; Cartmell and Schoepp, 2000).

Figure 1.

Interaction of mGluR5 with scaffolding proteins and signaling molecules. The SH3-multiple ankyrin domain-containing protein (Shank) is a prototypical PDZ scaffolding protein. The PDZ domain of Shank interacts with the c terminus of guanylate kinase-associated protein (GKAP), which is in turn associated with the ionotropic glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-PSD95 complex. The proline rich domain of Shank interacts with the EVH domain of Homer proteins. Homer proteins form multimers through interactions of their coiled-coil domain and link Shank to mGluR5 and inositol triphosphate (IP3) or ryanodine receptors. Homer interactions with mGluR5 are further regulated by Preso1 scaffolding proteins. mGluR5 activation by glutamate initiates Gq protein signaling that regulates the function of phospholipase C (PLC). Activation of PLC results in the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to release the second messengers 1,2-Diacylglycerol (DAG) and IP3. DAG is the physiological activator of protein kinase C (PKC), which in turn activates various intracellular signaling cascades. IP3 binds to intracellular IP3 receptors (IP3R) on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane initiating Ca2+ release from the ER lumen into the cytoplasm, generating complex Ca2+ concentration-dependent signals, including temporal oscillations, and propagating waves.

Group I mGluRs have been a major focus of investigation, particularly mGluR5, which is further subdivided into two structurally different receptor isoforms, named mGluR5a and mGluR5b (Minakami et al., 1993; Joly et al., 1995). mGluR5 is found in almost all brain regions, where through development mGluR5a is the predominant isoform during the early postnatal period, and mGluR5b is more highly expressed in the adult (Minakami et al., 1993; Romano et al., 1996). During development, mGluR5 is present in cells surrounding the lateral ventricle of the embryonic brain, as well as the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the postnatal brain (Di Giorgi Gerevini et al., 2004; Di Giorgi-Gerevini et al., 2005). Here, during these early developmental stages, mGluR5 function is involved in both synaptogenesis and the patterning of neural circuits (Catania et al., 1994; Park et al., 2007; Wijetunge et al., 2008). Importantly, the activity of mGluR5 is influenced by a number of postsynaptic proteins, such as the scaffolding proteins Homer and Shank, which also have significant developmental roles (Tu et al., 1999; Giuffrida et al., 2005; Ronesi et al., 2012).

Given that mGluR5 regulates various mechanisms implicated in neurogenesis and synaptic maintenance, it is interesting to note emerging evidence suggesting that aberrant regulation of mGluR5 leads to mental disorders with strong developmental and synaptic origins. These include Fragile X syndrome (FXS; Dolen and Bear, 2008; Levenga et al., 2011), autism spectrum disorder (Silverman et al., 2010; Mehta et al., 2011; Won et al., 2012), and schizophrenia (Liu et al., 2008; Vardigan et al., 2010; Carlisle et al., 2011). mGluR5 dysregulation in the aged brain is now also emerging as a key mediator of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology, in which synaptic maintenance is strongly impaired (Lee et al., 1995, 2004; Li et al., 2009). Here we shall discuss the role of mGluR5 in synaptic diseases and review the increasing number of candidate drugs targeting the receptor for efficacious treatment in a range of developmental and synaptic diseases.

mGluR5 and Associated Postsynaptic Proteins

Metabotropic glutamate receptors are tightly regulated by their association with scaffolding proteins. Homer, a member of a postsynaptic family of scaffolding proteins, has been shown to interact with group I mGluRs (Brakeman et al., 1997). Homer proteins exert effects on both the localization and signaling of mGluRs (Thomas, 2002). Specifically, Homer can reduce mGluR5 coupling to postsynaptic effectors, such as the IP3 receptor (IP3R; Kammermeier and Worley, 2007) and regulate mGluR-mediated protein synthesis (Ronesi and Huber, 2008). Understanding the mechanisms underlying the association between scaffold proteins and mGluRs has now become an area of significant interest. A recent study suggests that mGluR5 regulation by proline-directed kinases, such as cyclin-dependent kinase-5 (cdk-5), leads to enhanced mGluR5-Homer binding. This in turn leads to a reduction in mGluR5-induced cytosolic Ca2+ increase, manifesting in a reduction in mGluR coupling to voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Hu et al., 2012). The authors identified that the novel scaffolding protein Preso1 also served to mediate this mechanism; as a multidomain scaffolding protein, Preso1 localized mGluR, Homer and proline-directed kinases, promoting the phosphorylation of mGluR, and subsequent binding of Homer (Hu et al., 2012).

Shank, a family of postsynaptic proteins that function as part of the NMDA receptor (NMDAR)-associated PSD-95 complex, is another mGluR5 regulating scaffolding protein thought critical in mGluR function. Shank clusters mGluR5 and mediates the co-clustering of Homer with PSD-95/GKAP. Thus, Shank may cross-link Homer and PSD-95 complexes in the postsynaptic density and play a role in the signaling mechanisms of both mGluR5 and NMDARs (Tu et al., 1999). Indeed, synergistic interactions between mGluR5 and NMDARs have previously been identified, whereby activation of mGluR5 enhances NMDAR function (Gregory et al., 2011; Won et al., 2012). Additionally, mGluR5 has been shown to drive experience dependent changes in NMDAR subunit composition (Matta et al., 2011). It has also been revealed that an interaction between Shank1B and Homer1b is required for mGluR5-mediated IP3 generation and ensuing Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (Sala et al., 2005), suggesting a further complexity to the regulation of mGluR5 function by multiple coordinating scaffolding proteins.

mGluR5 and Synaptic Disease

mGluR5 has been studied as a fine regulator in both embryonic and postnatal neurogenesis (Di Giorgi Gerevini et al., 2004; Di Giorgi-Gerevini et al., 2005; Castiglione et al., 2008). mGluR5 function is therefore critical for synapse formation during brain development, suggesting that dysregulation of mGluR5 signaling might lead to developmental synaptic disorders. Accordingly, the modification of particular mGluR5 scaffolding proteins has been implicated in synaptic diseases and psychiatric disorders (Box 1). It has recently been suggested that dysregulation of Shank could be involved in schizophrenia-induced signaling cascades (Grabrucker et al., 2011). Studies have revealed that two de novo mutations in Shank3 are present in a subset of schizophrenia patients (Gauthier et al., 2010) and a Shank1 promoter variant leads to significant working memory deficits in schizophrenia (Durand et al., 2012; Lennertz et al., 2012), suggesting common Shank variants may contribute to neuropsychological dysfunctions in schizophrenia. Furthermore, limited studies also suggest mice lacking mGluR5 show schizophrenia-related behaviors including abnormal locomotor patterns, reduced pre-pulse inhibition (PPI), and deficits on performance of a short-term spatial memory task on the Y-maze (Gray et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2010), suggesting that positive modulation of mGluR5 function would be a viable target for schizophrenia therapeutics. However, to date, research into the aberrant signaling mechanisms underlying the etiology of schizophrenia have not identified synergistic roles for scaffolding proteins and mGluR5 activity, and further studies are required to elucidate any molecular coupling of these pathways.

Box 1. Translational concepts through targeting mGluR5.

Excessive mGluR5 activation has already been alluded to as a potential contributing factor in synaptic disorders, and a number of studies are currently testing the therapeutic potential of drugs that modify mGluR5 signaling through inhibition (Dolen et al., 2010). For these reasons, the development of mGluR5 ligands to combat synaptic diseases has become a highly attractive therapeutic area to pursue (Table 1).

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Iossifov et al. (2012) recently described overlap between autism susceptibility genes and the FMR1 gene, involved in FXS, after performing genetic sequencing of autistic children. Among the 59 new autism genes discovered, 14 were associated with fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), which is associated with both FXS and regulation of the gene encoding mGluR5 (Sokol et al., 2011). Therefore, given the supposed role of mGluR5 in FXS and autism, the receptor provides an attractive target for drug discovery in these disorders and a number of candidate compounds including mGluR5 negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) have progressed through to Phase II/III clinical trials.

Epilepsy

Although no significant clinical trials targeting mGluR5 in epilepsy have so far been performed, group I mGluRs, have been implicated in the disease, a common neurological disorder that occurs more frequently in children than in adulthood (Hauser and Hersdorffer, 1990). Epilepsy is also the most common neurological abnormality in FXS, occurring in approximately 20% of cases, presenting as seizures and EEG abnormalities (Musumeci et al., 1988). Agonists of group I mGluRs act as convulsants (Conn and Pin, 1997), and selective group I mGluR antagonists block seizures in rodent models of epilepsy (Chapman et al., 2000; Yan et al., 2005). It is thought that mGluR1 activation plays a role in sustaining the expression of prolonged bursts, whereas mGluR5 activation may be a contributor to the induction process underlying the epileptogenesis (Stoop et al., 2003). Therefore, blockade of mGluR5 receptors may also be worth exploring as adjunctive strategies for the treatment of seizures.

Schizophrenia

There is a growing indication of a specific involvement of mGluR5 in schizophrenia. Recent therapeutic strategies for the treatment of schizophrenia focus on the pharmacological interaction between mGluR5 and NMDA receptors (NMDARs; Homayoun et al., 2004; Stefani and Moghaddam, 2010), as it is well established that mGluR5 synergistically facilitates NMDAR function to alleviate the cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia (Awad et al., 2000; Attucci et al., 2001; Pisani et al., 2001; Rosenbrock et al., 2010). Moreover, activation of mGluR5 receptors with an agonist or positive allosteric modulator (PAM), such as CDPPB, ADX47273, MPPA, VU0092273, VU0360172, or ADX63365 has shown anti-psychotic-like properties, potentially providing therapeutic efficacy (Conn et al., 2009; Krystal et al., 2010; Niswender and Conn, 2010).

In summary, a number of neurological disorders of developmental origin are promising candidates for mGluR5-targeted therapeutics. Clearly, the balance of mGluR5 activation and inhibition is a critical parameter for healthy formation of neural circuits during development. This concept also extends into the aged brain, where dysregulation of mGluR5 function can have detrimental effects upon synaptic maintenance.

Table 1.

mGluR5 modulators in clinical trials.

| Compound | Mechanism | Indication | Clinical T phase | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFQ056 | mGluR5 NAM | Fragile X syndrome/PD-LID/Huntington’s chorea/GERD | II/III in fragile X syndrome; II in PD-LID; II in Huntington’s chorea (halted); IIb in GERD (halted) | Novartis |

| RO4917523 | mGluR5 antagonist | Depression/fragile X syndrome | IIa in depression; II in fragile X syndrome | Roche |

| ADX48621 | mGluR5 NAM | PD-LID, focal dystonia | II in PD-LID, focal dystonia | Addex |

| ADX63365 | mGluR5 PAM | Schizophrenia, cognition | Pre-clinical trial in schizophrenia | Addex, Merck and Co |

| STX107 | mGluR5 antagonist | Fragile X syndrome | II in fragile X syndrome | Seaside therapeutics |

| AZD2516 | mGluR5 antagonist | Chronic neuropathic pain/major depression | I/II in healthy volunteers | AstraZeneca |

| Fenobam | mGluR5 antagonist | Fragile X syndrome/pain | II/pre-clinical in bladder pain | Neuropharm |

Deletion of Shank proteins including Shank1 and 2 is believed to produce autism spectrum disorder-like phenotypes (Sato et al., 2012; Won et al., 2012). Recent reports using Shank2 knockout mice, which exhibit an autistic phenotype, showed increased mGluR5 activity and a subsequent decrease in AMPAR synaptic transmission and excessive synapse silencing, further supporting the importance of mGluR5 regulation by scaffolding proteins in synaptogenesis and synaptic disease (Won et al., 2012).

Excessive signaling of mGluR5 is also thought to account for multiple cognitive and syndromic features of FXS, the most common inherited form of mental retardation and autism (Dolen and Bear, 2008). A fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) knockout model of FXS induces excessive mGluR5 activation through an increased interaction between mGluR5 and the short Homer isoform, Homer 1a (Ronesi et al., 2012). Furthermore, genetic deletion of Homer 1a, which enhances mGluR5 association with long Homer isoforms, corrected several phenotypes in the FMRP knockout model of FXS, although mGluR-dependent long-term depression (LTD) was not rescued (Ronesi et al., 2012). These findings support the hypothesis that aberrant regulation of mGluR5 can lead to developmental synaptic disorders.

mGluR5 and Aβ: Convergence in Synaptic Dysfunction

It is widely accepted that certain forms of oligomeric amyloid-beta (Aβ) cause neurotoxicity and contribute to the pathogenesis of AD (Huang and Mucke, 2012). For example, it is now well established that Aβ oligomers, the primary pathology-inducing peptide of AD, can cause synaptic dysfunction, manifesting in the inhibition of long-term potentiation (LTP; Walsh et al., 2002; Shankar et al., 2008; Jo et al., 2011) and the enhancement of LTD (Hsieh et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009). These two forms of synaptic plasticity, exhibited in response to differential neural activity patterns, are believed by many to be the cellular mechanism of learning and memory, the loss of which is a major symptom in AD (Shankar et al., 2008).

Interestingly, it is now known that mGluR5 plays an important role in synaptic plasticity. This is the result of extensive research dedicated to elucidating the involvement of mGluR5 in LTP (Bashir et al., 1993; Bortolotto and Collingridge, 1993) and LTD (Oliet et al., 1997; Bellone et al., 2008). In line with this, recent data confirms positive modulation of mGluR5 induces an enhancement of learning and memory in the normal state as well as in the NMDAR dysfunction-induced amnesic state (Homayoun and Moghaddam, 2010; Rosenbrock et al., 2010; Stefani and Moghaddam, 2010; Menard and Quirion, 2012).

Although limited data directly associates mGluR5 signaling with AD, studies have shown potential mechanistic interactions between AD-associated molecules and mGluR5. Groups focused on molecular pathways in Autism and FXS suggest that activation of mGluR5 removes the repressive effect of the FMRP on amyloid precursor protein (APP) mRNA translation and stimulates secretion of APP (Sokol et al., 2011), the precursor to Aβ peptide generation. Inhibitors of mGluR5 have been shown to reduce Aβ production and to have positive effects upon disease phenotypes in rodent models of FXS and AD (Malter et al., 2010). Together, this suggests aberrant mGluR5 activation may positively regulate the processing of Aβ oligomers leading to disease pathology.

Recent translational studies have also shown that Aβ-mediated impairment of LTP can be attenuated by co-treatment with the mGluR5 antagonist, MPEP (Wang et al., 2004; Rammes et al., 2011), suggesting mGluR5 may be an efficacious target for the treatment of AD. However, although MPEP is characterized as an effective mGluR5 antagonist, a non-specific action as a non-competitive NMDAR antagonist could potentially provide the observed neuroprotective effects (O’Leary et al., 2000).

Evidence for a direct mechanistic interaction between mGluR5 and Aβ was identified by Renner et al. (2010) using quantum dot tagged oligomers of Aβ to show that clustering of Aβ at the membrane greatly reduced the ability of mGluR5 to laterally diffuse from the synapse, resulting in facilitation of mGluR5-mediated signaling. Additionally, Aβ binding to the neuronal surface of hippocampal cultured neurons from mGluR5 knockout mice was greatly reduced, suggesting that mGluR5 may play a reciprocal role in “scaffolding” Aβ oligomer clusters to the synapses. Together these findings hint at a synergistic interaction between Aβ and mGluR5, resulting in the over-activation of mGluR5 with subsequent pathological effects upon NMDAR function and Ca2+ homeostasis (Renner et al., 2010).

Finally, Aβ-mediated activation of mGluR5 may inhibit the function of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChR) leading to cholinergic hypofunction, a hallmark of AD pathogenesis closely linked to Aβ and Tau neuropathologies (Fisher, 2012). Indeed, aberrant expression of mGluR5 leads to the inhibition of mAChR-mediated long-term synaptic depression in the perirhinal cortex (Jo et al., 2006) and acute nicotine-mediated enhancement of LTP in the rat dentate gyrus can be inhibited by MPEP (Welsby et al., 2006). Thus, mGluR5 dysregulation has been proposed as a key step in AD pathology, marking mGluR5 as a possible target to tackle synaptic dysfunction in AD. However, more effort to shed light on the mechanism of action of mGluR5 will be required prior to the effective development of receptor-based treatments for AD.

Concluding Remarks

In the past several years, significant progress has been made into the understanding of mGluR5 receptor function in health and disease. Studies suggest that the mGluR5 receptor has an important role in synaptogenesis and the regulation of synaptic plasticity. Thus, it seems aberrant mGluR5 regulation and signaling may play a part in a number of synaptic disorders, including a novel role in AD. Therapeutic treatments are slowly coming to the fore in many of these disorders. However, more research into the underlying involvement of this promiscuous receptor in synaptic-related disorders will ensure more efficacious treatments can be developed in the future.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Anwyl R. (1992). Metabotropic glutamate receptors: electrophysiological properties and role in plasticity. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 217–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronica E., Catania M. V., Geurts J., Yankaya B., Troost D. (2001). Immunohistochemical localization of group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptors in control and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis human spinal cord: upregulation in reactive astrocytes. Neuroscience 105, 509–520 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00181-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attucci S., Carla V., Mannaioni G., Moroni F. (2001). Activation of type 5 metabotropic glutamate receptors enhances NMDA responses in mice cortical wedges. Br. J. Pharmacol. 132, 799–806 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad H., Hubert G. W., Smith Y., Levey A. I., Conn P. J. (2000). Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 has direct excitatory effects and potentiates NMDA receptor currents in neurons of the subthalamic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 20, 7871–7879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir Z. I., Bortolotto Z. A., Davies C. H., Berretta N., Irving A. J., Seal A. J., et al. (1993). Induction of LTP in the hippocampus needs synaptic activation of glutamate metabotropic receptors. Nature 363, 347–350 10.1038/363347a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellone C., Luscher C., Mameli M. (2008). Mechanisms of synaptic depression triggered by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2913–2923 10.1007/s00018-008-8263-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J., Irvine R. F. (1984). Inositol trisphosphate, a novel second messenger in cellular signal transduction. Nature 312, 315–321 10.1038/312315a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthele A., Platzer S., Laurie D. J., Weis S., Sommer B., Zieglgansberger W., et al. (1999). Expression of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype mRNA (mGluR1-8) in human cerebellum. Neuroreport 10, 3861–3867 10.1097/00001756-199912160-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotto Z. A., Collingridge G. L. (1993). Characterisation of LTP induced by the activation of glutamate metabotropic receptors in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 32, 1–9 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90123-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakeman P. R., Lanahan A. A., O’Brien R., Roche K., Barnes C. A., Huganir R. L., et al. (1997). Homer: a protein that selectively binds metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature 386, 284–288 10.1038/386284a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle H. J., Luong T. N., Medina-Marino A., Schenker L., Khorosheva E., Indersmitten T., et al. (2011). Deletion of densin-180 results in abnormal behaviors associated with mental illness and reduces mGluR5 and DISC1 in the postsynaptic density fraction. J. Neurosci. 31, 16194–16207 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1097-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartmell J., Schoepp D. D. (2000). Regulation of neurotransmitter release by metabotropic glutamate receptors. J. Neurochem. 75, 889–907 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750889.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione M., Calafiore M., Costa L., Sortino M. A., Nicoletti F., Copani A. (2008). Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors control proliferation, survival and differentiation of cultured neural progenitor cells isolated from the subventricular zone of adult mice. Neuropharmacology 55, 560–567 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania M. V., Landwehrmeyer G. B., Testa C. M., Standaert D. G., Penney J. B., Jr., Young A. B. (1994). Metabotropic glutamate receptors are differentially regulated during development. Neuroscience 61, 481–495 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90428-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman A. G., Nanan K., Williams M., Meldrum B. S. (2000). Anticonvulsant activity of two metabotropic glutamate group I antagonists selective for the mGlu5 receptor: 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), and (E)-6-methyl-2-styryl-pyridine (SIB 1893). Neuropharmacology 39, 1567–1574 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00242-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. H., Stoker A., Markou A. (2010). The glutamatergic compounds sarcosine and N-acetylcysteine ameliorate prepulse inhibition deficits in metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor knockout mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 209, 343–350 10.1007/s00213-010-1802-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn P. J., Lindsley C. W., Jones C. K. (2009). Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors as a novel approach for the treatment of schizophrenia. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 30, 25–31 10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn P. J., Pin J. P. (1997). Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 37, 205–237 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giorgi Gerevini V. D., Caruso A., Cappuccio I., Ricci Vitiani L., Romeo S., Della Rocca C., et al. (2004). The mGlu5 metabotropic glutamate receptor is expressed in zones of active neurogenesis of the embryonic and postnatal brain. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 150, 17–22 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giorgi-Gerevini V., Melchiorri D., Battaglia G., Ricci-Vitiani L., Ciceroni C., Busceti C. L., et al. (2005). Endogenous activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors supports the proliferation and survival of neural progenitor cells. Cell Death Differ. 12, 1124–1133 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolen G., Bear M. F. (2008). Role for metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) in the pathogenesis of fragile X syndrome. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 586, 1503–1508 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.150722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolen G., Carpenter R. L., Ocain T. D., Bear M. F. (2010). Mechanism-based approaches to treating fragile X. Pharmacol. Ther. 127, 78–93 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand C. M., Perroy J., Loll F., Perrais D., Fagni L., Bourgeron T., et al. (2012). SHANK3 mutations identified in autism lead to modification of dendritic spine morphology via an actin-dependent mechanism. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 71–84 10.1038/mp.2011.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A. (2012). Cholinergic modulation of amyloid precursor protein processing with emphasis on M1 muscarinic receptor: perspectives and challenges in treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 120(Suppl. 1), 22–33 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07507.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier J., Champagne N., Lafrenière R. G., Xiong L., Spiegelman D., Brustein E., et al. (2010). De novo mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 in patients ascertained for schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7863–7868 10.1073/pnas.0906232107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida R., Musumeci S., D’Antoni S., Bonaccorso C. M., Giuffrida-Stella A. M., Oostra B. A., et al. (2005). A reduced number of metabotropic glutamate subtype 5 receptors are associated with constitutive homer proteins in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 25, 8908–8916 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0932-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabrucker A. M., Schmeisser M. J., Schoen M., Boeckers T. M. (2011). Postsynaptic ProSAP/Shank scaffolds in the cross-hair of synaptopathies. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 594–603 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray L., van den Buuse M., Scarr E., Dean B., Hannan A. J. (2009). Clozapine reverses schizophrenia-related behaviours in the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 knockout mouse: association with N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor up-regulation. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 12, 45–60 10.1017/S1461145709009961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory K. J., Dong E. N., Meiler J., Conn P. J. (2011). Allosteric modulation of metabotropic glutamate receptors: structural insights and therapeutic potential. Neuropharmacology 60, 66–81 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser W., Hersdorffer D. (1990). Epilepsy: Frequency, Causes and Consequences. New York: Demos [Google Scholar]

- Homayoun H., Moghaddam B. (2010). Group 5 metabotropic glutamate receptors: role in modulating cortical activity and relevance to cognition. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 639, 33–39 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homayoun H., Stefani M. R., Adams B. W., Tamagan G. D., Moghaddam B. (2004). Functional interaction between NMDA and mGlu5 receptors: effects on working memory, instrumental learning, motor behaviors, and dopamine release. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1259–1269 10.1038/sj.npp.1300417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H., Boehm J., Sato C., Iwatsubo T., Tomita T., Sisodia S., et al. (2006). AMPAR removal underlies Abeta-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron 52, 831–843 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J. H., Yang L., Kammermeier P. J., Moore C. G., Brakeman P. R., Tu J., et al. (2012). Preso1 dynamically regulates group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 836–844 10.1038/nn.3103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Mucke L. (2012). Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell 148, 1204–1222 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iossifov I., Ronemus M., Levy D., Wang Z., Hakker I., Rosenbaum J., et al. (2012). De novo gene disruptions in children on the autistic spectrum. Neuron 74, 285–299 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J., Ball S. M., Seok H., Oh S. B., Massey P. V., Molnar E., et al. (2006). Experience-dependent modification of mechanisms of long-term depression. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 170–172 10.1038/nn1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J., Whitcomb D. J., Olsen K. M., Kerrigan T. L., Lo S. C., Bru-Mercier G., et al. (2011). Abeta(1-42) inhibition of LTP is mediated by a signaling pathway involving caspase-3, Akt1 and GSK-3beta. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 545–547 10.1038/nn.2785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly C., Gomeza J., Brabet I., Curry K., Bockaert J., Pin J. P. (1995). Molecular, functional, and pharmacological characterization of the metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5 splice variants: comparison with mGluR1. J. Neurosci. 15, 3970–3981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong Y. J., Kumar V., O’Malley K. L. (2009). Intracellular metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) activates signaling cascades distinct from cell surface counterparts. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35827–35838 10.1074/jbc.M109.046276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammermeier P. J., Worley P. F. (2007). Homer 1a uncouples metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 from postsynaptic effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 6055–6060 10.1073/pnas.0608991104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal J. H., Mathew S. J., D’Souza D. C., Garakani A., Gunduz-Bruce H., Charney D. S. (2010). Potential psychiatric applications of metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists and antagonists. CNS Drugs 24, 669–693 10.2165/11533230-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Fahey P. G., Jong Y. J., Ramanan N., O’Malley K. L. (2012). Activation of intracellular metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in striatal neurons leads to up-regulation of genes associated with sustained synaptic transmission including Arc/Arg3.1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 5412–5425 10.1074/jbc.M111.313619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. G., Ogawa O., Zhu X., O’Neill M. J., Petersen R. B., Castellani R. J., et al. (2004). Aberrant expression of metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 in the vulnerable neurons of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 107, 365–371 10.1007/s00401-004-0820-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. K., Wurtman R. J., Cox A. J., Nitsch R. M. (1995). Amyloid precursor protein processing is stimulated by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 8083–8087 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennertz L., Wagner M., Wolwer W., Schuhmacher A., Frommann I., Berning J., et al. (2012). A promoter variant of SHANK1 affects auditory working memory in schizophrenia patients and in subjects clinically at risk for psychosis. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 262, 117–124 10.1007/s00406-011-0233-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenga J., Hayashi S., de Vrij F. M., Koekkoek S. K., van der Linde H. C., Nieuwenhuizen I., et al. (2011). AFQ056, a new mGluR5 antagonist for treatment of fragile X syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 42, 311–317 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Hong S., Shepardson N. E., Walsh D. M., Shankar G. M., Selkoe D. (2009). Soluble oligomers of amyloid beta protein facilitate hippocampal long-term depression by disrupting neuronal glutamate uptake. Neuron 62, 788–801 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Grauer S., Kelley C., Navarra R., Graf R., Zhang G., et al. (2008). ADX47273 [S-(4-fluoro-phenyl)-{3-[3-(4-fluoro-phenyl)-[1,2,4]-oxadiazol-5-yl]-piperidin-1-yl}-methanone]: a novel metabotropic glutamate receptor 5-selective positive allosteric modulator with preclinical antipsychotic-like and procognitive activities. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 327, 827–839 10.1124/jpet.108.141051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bendito G., Shigemoto R., Fairen A., Lujan R. (2002). Differential distribution of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors during rat cortical development. Cereb. Cortex 12, 625–638 10.1093/cercor/12.6.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malter J. S., Ray B. C., Westmark P. R., Westmark C. J. (2010). Fragile X syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease: another story about APP and beta-amyloid. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 7, 200–206 10.2174/156720510791050957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta J. A., Ashby M. C., Sanz-Clemente A., Roche K. W., Isaac J. T. (2011). mGluR5 and NMDA receptors drive the experience- and activity-dependent NMDA receptor NR2B to NR2A subunit switch. Neuron 70, 339–351 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta M. V., Gandal M. J., Siegel S. J. (2011). mGluR5-antagonist mediated reversal of elevated stereotyped, repetitive behaviors in the VPA model of autism. PLoS ONE 6, e26077. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard C., Quirion R. (2012). Successful cognitive aging in rats: a role for mGluR5 glutamate receptors, homer 1 proteins and downstream signaling pathways. PLoS ONE 7, e28666. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakami R., Katsuki F., Sugiyama H. (1993). A variant of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5: an evolutionally conserved insertion with no termination codon. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 194, 622–627 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci S. A., Colognola R. M., Ferri R., Gigli G. L., Petrella M. A., Sanfilippo S., et al. (1988). Fragile-X syndrome: a particular epileptogenic EEG pattern. Epilepsia 29, 41–47 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb05096.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender C. M., Conn P. J. (2010). Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 50, 295–322 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary D. M., Movsesyan V., Vicini S., Faden A. I. (2000). Selective mGluR5 antagonists MPEP and SIB-1893 decrease NMDA or glutamate-mediated neuronal toxicity through actions that reflect NMDA receptor antagonism. Br. J. Pharmacol. 131, 1429–1437 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliet S. H., Malenka R. C., Nicoll R. A. (1997). Two distinct forms of long-term depression coexist in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Neuron 18, 969–982 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80336-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H., Varadi A., Seok H., Jo J., Gilpin H., Liew C. G., et al. (2007). mGluR5 is involved in dendrite differentiation and excitatory synaptic transmission in NTERA2 human embryonic carcinoma cell-derived neurons. Neuropharmacology 52, 1403–1414 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A., Gubellini P., Bonsi P., Conquet F., Picconi B., Centonze D., et al. (2001). Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 mediates the potentiation of N-methyl-D-aspartate responses in medium spiny striatal neurons. Neuroscience 106, 579–587 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00297-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammes G., Hasenjager A., Sroka-Saidi K., Deussing J. M., Parsons C. G. (2011). Therapeutic significance of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors and mGluR5 metabotropic glutamate receptors in mediating the synaptotoxic effects of beta-amyloid oligomers on long-term potentiation (LTP) in murine hippocampal slices. Neuropharmacology 60, 982–990 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner M., Lacor P. N., Velasco P. T., Xu J., Contractor A., Klein W. L., et al. (2010). Deleterious effects of amyloid beta oligomers acting as an extracellular scaffold for mGluR5. Neuron 66, 739–754 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano C., van den Pol A. N., O’Malley K. L. (1996). Enhanced early developmental expression of the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 in rat brain: protein, mRNA splice variants, and regional distribution. J. Comp. Neurol. 367, 403–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronesi J. A., Collins K. A., Hays S. A., Tsai N. P., Guo W., Birnbaum S. G., et al. (2012). Disrupted Homer scaffolds mediate abnormal mGluR5 function in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 431–440, S431. 10.1038/nn.3033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronesi J. A., Huber K. M. (2008). Homer interactions are necessary for metabotropic glutamate receptor-induced long-term depression and translational activation. J. Neurosci. 28, 543–547 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5019-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbrock H., Kramer G., Hobson S., Koros E., Grundl M., Grauert M., et al. (2010). Functional interaction of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 and NMDA-receptor by a metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 positive allosteric modulator. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 639, 40–46 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala C., Roussignol G., Meldolesi J., Fagni L. (2005). Key role of the postsynaptic density scaffold proteins Shank and Homer in the functional architecture of Ca2+ homeostasis at dendritic spines in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 25, 4587–4592 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4822-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato D., Lionel A. C., Leblond C. S., Prasad A., Pinto D., Walker S., et al. (2012). SHANK1 deletions in males with autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 879–887 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G. M., Li S., Mehta T. H., Garcia-Munoz A., Shepardson N. E., Smith I., et al. (2008). Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 14, 837–842 10.1038/nm1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R., Kinoshita A., Wada E., Nomura S., Ohishi H., Takada M., et al. (1997). Differential presynaptic localization of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 17, 7503–7522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. L., Tolu S. S., Barkan C. L., Crawley J. N. (2010). Repetitive self-grooming behavior in the BTBR mouse model of autism is blocked by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 976–989 10.1038/npp.2009.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol D. K., Maloney B., Long J. M., Ray B., Lahiri D. K. (2011). Autism, Alzheimer disease, and fragile X: APP, FMRP, and mGluR5 are molecular links. Neurology 76, 1344–1352 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166dc7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani M. R., Moghaddam B. (2010). Activation of type 5 metabotropic glutamate receptors attenuates deficits in cognitive flexibility induced by NMDA receptor blockade. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 639, 26–32 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoop R., Conquet F., Pralong E. (2003). Determination of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes involved in the frequency of epileptiform activity in vitro using mGluR1 and mGluR5 mutant mice. Neuropharmacology 44, 157–162 10.1016/S0028-3908(02)00377-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas U. (2002). Modulation of synaptic signalling complexes by Homer proteins. J. Neurochem. 81, 407–413 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00869.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu J. C., Xiao B., Naisbitt S., Yuan J. P., Petralia R. S., Brakeman P., et al. (1999). Coupling of mGluR/Homer and PSD-95 complexes by the Shank family of postsynaptic density proteins. Neuron 23, 583–592 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80810-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardigan J. D., Huszar S. L., McNaughton C. H., Hutson P. H., Uslaner J. M. (2010). MK-801 produces a deficit in sucrose preference that is reversed by clozapine, D-serine, and the metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor positive allosteric modulator CDPPB: relevance to negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia? Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 95, 223–229 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D. M., Klyubin I., Fadeeva J. V., Cullen W. K., Anwyl R., Wolfe M. S., et al. (2002). Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416, 535–539 10.1038/416535a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Westin L., Nong Y., Birnbaum S., Bendor J., Brismar H., et al. (2009). Norbin is an endogenous regulator of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 signaling. Science 326, 1554–1557 10.1126/science.1177627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Walsh D. M., Rowan M. J., Selkoe D. J., Anwyl R. (2004). Block of long-term potentiation by naturally secreted and synthetic amyloid beta-peptide in hippocampal slices is mediated via activation of the kinases c-Jun N-terminal kinase, cyclin-dependent kinase 5, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase as well as metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5. J. Neurosci. 24, 3370–3378 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3727-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsby P., Rowan M., Anwyl R. (2006). Nicotinic receptor-mediated enhancement of long-term potentiation involves activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors and ryanodine-sensitive calcium stores in the dentate gyrus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24, 3109–3118 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05187.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijetunge L. S., Till S. M., Gillingwater T. H., Ingham C. A., Kind P. C. (2008). mGluR5 regulates glutamate-dependent development of the mouse somatosensory cortex. J. Neurosci. 28, 13028–13037 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2600-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won H., Lee H. R., Gee H. Y., Mah W., Kim J. I., Lee J., et al. (2012). Autistic-like social behaviour in Shank2-mutant mice improved by restoring NMDA receptor function. Nature 486, 261–265 10.1038/nature11208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q. J., Rammal M., Tranfaglia M., Bauchwitz R. P. (2005). Suppression of two major fragile X syndrome mouse model phenotypes by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropharmacology 49, 1053–1066 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirpel L., Janowiak M. A., Taylor D. A., Parks T. N. (2000). Developmental changes in metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated calcium homeostasis. J. Comp. Neurol. 421, 95–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]