Abstract

AIM: To study if the angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) losartan counteracts pancreatic hyperenzymemia as measured 24 h after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

METHODS: A triple-blind and placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was performed at two Swedish hospitals in 2006-2008. Patients over 18 years of age undergoing ERCP, excluding those with current pancreatitis, current use of ARB, and severe disease, such as sepsis, liver and renal failure. One oral dose of 50 mg losartan or placebo was given one hour before ERCP. The relative risk of hyperenzymemia 24 h after ERCP was estimated using multivariable logistic regression, and expressed as odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), including adjustment for potential remaining confounding.

RESULTS: Among 76 participating patients, 38 were randomized to the losartan and the placebo group, respectively. The incidence rates of hyperenzymemia and acute pancreatitis among all 76 participating patients were 21% and 12%, respectively. Hyperenzymemia was detected in 9 and 7 patients in the losartan and placebo group, respectively. There were no major differences between the comparison groups regarding cannulation difficulty, findings, or proportion of patients requiring drainage of the bile ducts. There were, however, more pancreatic duct injections, a greater extent of pancreatography, and more biliary sphincterotomies in the losartan group than in the placebo group. Losartan was not associated with risk of hyperenzymemia compared to the placebo group after multi-varible logistic regression analysis (odds ratio 1.6, 95%CI 0.3-7.8).

CONCLUSION: In this randomized trial 50 mg losartan given orally had no prophylactic effect on development of hyperenzymemia after ERCP.

Keywords: Renin-angiotensin system, Pancreatitis, Prophylaxis, Placebo-controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis is a serious complication after endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) affecting 1%-10% of the patients[1-5]. Elevation of pancreatic enzymes in serum (hyperenzymemia) is linked with pancreatitis, and occurs in 25%-40% of the patients after ERCP[1,2,6,7]. Known risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis include female sex, previous pancreatitis, and procedure-related factors, including pancreatic duct injection, cannulation difficulties, and use of sphincterotomy[3-5]. Several agents have been evaluated in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis in clinical trials. Some groups of medications have not been associated with convincing effects, e.g., anti-secretary drugs[6,8-15], protease inhibitors[1,2,6,16-21], heparin[22], and other anti-inflammatory drugs[7,23-25]. Other drugs, however, have shown promising effects, e.g., interleukin 10[26], glyceryl trinitrate[27], and antibiotics[28]. To date, however, there is no established medical prophylaxis against pancreatitis after ERCP. There is support for the new hypothesis that angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers (ARB) prevent the development of pancreatitis or pancreatic hyperenzymemia after ERCP. Acute pancreatitis activates a local pancreatic renin-angiotensin system as well as the circulating renin-angiotensin system[29,30]. Experimental research has shown that the angiotensin II type receptor and angiotensinogen are highly expressed in inflamed pancreatic tissue, and that administration of angiotensin II increases the secretion of pancreatic enzymes[31]. This increased secretion can in turn be blocked by the ARB losartan (Cozaar®)[31,32]. Moreover, losartan can prevent induced acute pancreatitis in rats[32-34]. Furthermore, a recent case-control study by our group indicated a decreased risk of acute pancreatitis among patients treated with ARB[35]. We have therefore conducted a clinical trial to test whether losartan prevents pancreatic hyperenzymemia after ERCP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A triple-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial was performed at two Swedish hospitals, Karolinska University Hospital and Kalmar County Hospital, during the study period May 1, 2006 through October 31, 2008. There was a temporary intermission in the inclusion of patients during the period October 31, 2007 to May 1, 2008 to allow manufacturing of additional placebo capsules because of a restricted durability. The performing endoscopists recruited study patients. A capsule of 50 mg losartan or an identical capsule of placebo was given orally one hour before the ERCP. The dose was selected to minimize adverse side effects and yet ensure adequate penetration to the pancreatic tissue[36,37]. The capsules were manufactured by Apoteket AB Produktion och Laboratoriers. The primary study outcome was occurrence of hyperenzymemia 24 h after ERCP. Hyperenzymemia was defined as plasma levels of pancreatic amylase or lipase at least three times above the upper reference level. Post-ERCP pancreatitis was a secondary outcome, defined as persistent upper abdominal pain combined with hyperenzymemia 24 h after ERCP.

Patients

Eligible for the study were patients older than 18 years, scheduled for ERCP. The study aimed to investigate first-time ERCP patients, and therefore set an arbitrarily chosen time limit to one year since last ERCP to be included in the study. Other exclusion criteria were: previous ERCP within one year, current elevation of pancreatic amylase or lipase, ongoing acute or chronic pancreatitis, current use of ARB or angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitor, bilateral renal artery stenosis (or unilateral in patients with a single kidney), known hypersensitivity to ARB, pregnancy, breastfeeding, or predefined severe disease (ongoing sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, acute circulatory collapse, severe dehydration, hypovolemia, severe renal insufficiency, or severe liver failure). The participating patients were asked about their medical history and underwent a physical examination. Measurements of blood pressure and heart rate, and assessment of pain on a Visual Analogue Scale were performed at baseline (one hour before the ERCP) and 24 h after the ERCP. Blood pressure and heart rate were also registered hourly until 6 h after the procedure, and later if needed. Blood samples were collected at baseline, and at one, four, and 24 h after the ERCP. In all other respects, the ERCP procedure and ensuing patient care followed the standard clinical routines.

Randomization and blinding

The included patients were randomized to the losartan group or the placebo group by use of consecutive closed study envelopes containing the individual study code, the case report form and the selected capsule. The study coordinator assigned active or placebo drug using computer generated random numbers. The randomization was made in blocks of 10 with equal distribution of active and placebo drugs at the participating centres. The study coordinator, who was not involved either in the patient care or in the analysis of the data, held the key to the study code. The participating patients, the endoscopists performing the ERCP, and the evaluators of the outcome were all kept unaware of the drug used until after the analyses.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

The included patients fasted for 6 h before the ERCP. During the ERCP procedure, the patients received midazolam or diazepam for sedation and ketobemidone (Ketogan®) for analgesia. Glucagon or butylscopolamine (Buscopan®) was given to reduce intestinal motility if needed. Omnipaque [140-240 mgI/mL (GE Healthcare, CA, United States)] was used as contrast medium to visualize the biliary and pancreatic ducts. All participating endoscopists were experienced in ERCP. The endoscopist documented the following data immediately after completing the ERCP: indication for ERCP, degree of cannulation difficulty [easy, medium, difficult (> 15 attempts or > 5 min for deep cannulation after initial cholangio- or pancreatography), or failed], findings, degree of contrast filling of the pancreatic duct, number of contrast injections in the pancreatic duct, endoscopic procedures and interventions performed, and duration of the procedure.

Ethics

All participants signed written informed consent before inclusion. The regional ethical committee in Stockholm and the Medical Products Agency in Sweden approved the study. The trial was registered according to regulation formulated by the European Medicines Agency and Good Clinical Practice[38,39].

Statistical analysis

The sample size was estimated on the basis of the following assumptions: (1) an incidence of hyperenzymemia of 40%; (2) a reduction of hyperenzymemia to 10% in the losartan group; (3) a significance level (alpha) of 0.05; and (4) a power of 80%. Using two-sample comparison of proportions, the corresponding sample size was 38 patients in each group. We evaluated all patients included in the group to which they were randomized, i.e., according to the analytical rule of intention to treat. To assess the impact of missing outcome data, we analyzed the data using the method of last observation carried forward[40]. The Fisher exact test or χ2 test was used for analysis of categorical variables. An analysis of variance or median test was performed for continuous data. To adjust for any imbalance of potentially confounding factors occurring in spite of randomization, we used multivariable logistic regression to estimate the relative risk of hyperenzymemia by calculating odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The following variables were adjusted for in the final multivariable model: sex, age (grouped into < or ≥ 65 years), body mass index (BMI, expressed as kg/m2 and categorized as < 20, 20-25, or > 25), history of pancreatitis (yes or no), study center (Karolinska University Hospital or Kalmar County Hospital), and ERCP duration (continuous variable). Other potential confounders, including degree of technical difficulties during ERCP, sphincterotomy, biliary drainage, and time between drug intake and ERCP, were tested in the regression model, but since they did not influence the risk estimates but only diluted the precision of the estimates they were not included in the final model. The statistical analyses were performed with SAS Statistical Package (version 9.0, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

RESULTS

Study participants and procedures

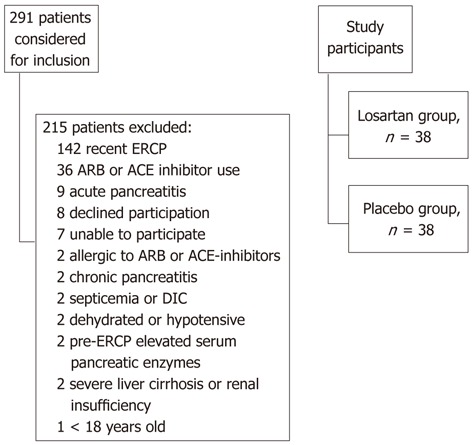

Among 291 patients considered for inclusion, 215 were excluded. The reasons for these exclusions are listed in Figure 1. The most common reason for exclusion was recent ERCP (n = 142). Among the remaining 76 patients, 38 were randomized to the losartan group and 38 to the placebo group. Some characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The distribution of patients between the participating centres was equal in the comparison groups. Men were overrepresented in the losartan group. The distributions by age, BMI, history of pancreatitis, and the indications for the ERCP were equal between the groups, although there were fewer patients with jaundice and cholangitis in the losartan group (Table 1). However, there were no statistically significant differences in between the groups. At baseline the mean arterial blood pressure was the same, 100 mm Hg, in the two groups, but 24 h after the ERCP it was lower in the losartan group than in the placebo group (93 mmHg vs 98 mmHg; P < 0.05). As shown in Table 2, there were no major differences between the comparison groups regarding cannulation difficulty, findings, or proportion of patients requiring drainage of the bile ducts. There were, however, more pancreatic duct injections, a greater extent of pancreatography, and more biliary sphincterotomies in the losartan group than in the placebo group (Table 2). No patient received pancreatic stent. No patients with especially high risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis entered the study, e.g., individuals with sphincter Oddi’s dysfunction, and no high risk procedures, e.g., sphincter Oddi manometry, duct balloon dilatation, or pancreatic sphincterotomy, were performed.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography and were considered for inclusion in the study. DIC: Disseminated intravascular coagulation; ECRP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ARB: Angiotensin II receptor blockers; ACE: Angiotensin I converting enzyme.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 76 participating patients and indications for their endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography n (%)

| Characteristic | Losartan group | Placebo group |

| Total | 38 (100) | 38 (100) |

| Study centre | ||

| Karolinska | 19 (50) | 19 (50) |

| Kalmar | 19 (50) | 19 (50) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 22 (58) | 16 (42) |

| Female | 16 (42) | 22 (58) |

| Age, yr | ||

| < 65 | 13 (34) | 14 (37) |

| ≥ 65 | 25 (66) | 24 (63) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| < 20 | 3 (8) | 2 (5) |

| 20-25 | 14 (37) | 14 (37) |

| > 25 | 7 (18) | 9 (24) |

| Unknown | 14 (37) | 13 (34) |

| Previous pancreatitis | ||

| No | 34 (89) | 35 (92) |

| Yes | 4 (11) | 3 (8) |

| Indication for ERCP1 | ||

| Jaundice without cholangitis | 20 (53) | 21 (55) |

| Jaundice with cholangitis | 7 (18) | 9 (24) |

| Suspected tumour in pancreas or bile ducts | 10 (26) | 13 (34) |

| Suspected benign disease, i.e., biliary lithiasis, stricture or other disease | 20 (53) | 16 (42) |

Since each procedure could have several indications, the sum of percentages could be > 100. ECRP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Table 2.

Distribution of procedure-related findings at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the 76 participating patients n (%)

| Finding/procedure1 | Losartan group | Placebo group |

| Total | 38 (100) | 38 (100) |

| Cannulation of the common bile duct | ||

| Cannulation difficulty2 | ||

| Easy or medium | 27 (71) | 27 (71) |

| Difficult or failed | 10 (26) | 9 (24) |

| Pancreatography | ||

| Number of pancreatic duct injections2 | ||

| None | 21 (55) | 24 (63) |

| 1-3 | 15 (39) | 11 (29) |

| ≥ 4 | 1 (3) | 2 (5) |

| Extent of pancreatography2 | ||

| None | 21 (55) | 24 (63) |

| Main duct | 12 (31) | 11 (29) |

| First branch, second branch, and acinarisation | 4 (11) | 2 (5) |

| Procedure-related findings in bile ducts2 | ||

| Normal | 5 (13) | 3 (8) |

| Gallstone | 13 (34) | 14 (37) |

| Suspected cancer | 6 (16) | 8 (21) |

| Dilatation, benign or undetermined stricture, or anomaly | 14 (37) | 10 (26) |

| Procedure-related findings in pancreas2 | ||

| Not contrast-fille | 21 (55) | 24 (63) |

| Normal | 13 (34) | 10 (26) |

| Suspected cancer | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Dilatation | 3 (8) | 1 (3) |

| Endoscopic procedure | ||

| Biliary sphincterotomy | ||

| No | 11 (29) | 14 (37) |

| Yes | 27 (71) | 24 (63) |

| Biliary stenting | ||

| No | 24 (63) | 23 (61) |

| Yes | 14 (37) | 15 (39) |

| ERCP time, min2 | ||

| < 30 | 13 (34) | 10 (26) |

| ≥ 30 | 22 (58) | 26 (68) |

| Time between intake of losartan or placebo capsule and ERCP, min | ||

| < 60 | 9 (24) | 7 (18) |

| ≥ 60 | 29 (76) | 31 (82) |

The endoscopist assessed degree of technical difficulty;

The total number of participants was 38 patients in each variable, and a sum < 38 indicate missing values between n = 2-5. ECRP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Pancreatic enzyme levels

The incidence rates of hyperenzymemia and acute pancreatitis among all 76 participating patients were 21% and 12%, respectively. In total, 9 patients in the losartan group and 7 patients in the placebo group showed hyperenzymemia 24 h after ERCP (P = 0.51) (Table 3). No decreased risk of hyperenzymemia was found in the losartan group compared to the placebo group in the multivariable adjusted regression model (OR 1.6, 95%CI 0.3-7.8). The median serum amylase concentration at baseline was similar in the two groups (0.44 in the losartan group and 0.46 in the placebo group; P = 0.64). No significant differences in the amylase or lipase values one hour post-ERCP in the comparison groups were seen (data not shown). There was no statistically significant difference in median serum amylase between the groups 24 h after ERCP (0.62 in the losartan group and 0.82 in the placebo group, P = 0.33). Hyperamylasemia occurred in 8 patients in the losartan group and in 4 patients in the placebo group (P = 0.53) (Table 3). Similarly, there was no substantial difference in serum lipase value between the groups either at baseline (0.53 and 0.48 in the losartan and placebo groups, respectively, P = 0.47) or 24 h after ERCP (0.77 and 1.07 in the losartan and placebo groups, respectively, P = 0.62). Eight patients had hyperlipasemia 24 h after ERCP in the losartan group, and 7 in the placebo group (P = 0.89) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Serum pancreatic enzyme levels, abdominal pain, and pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography among 76 participating patients1 n (%)

| Pancreatic enzyme level in serum | Losartan group | Placebo group | P value |

| Amylase (microkat/L), median, (interquartile range) | |||

| At baseline | 0.44 (0.3) | 0.46 (0.4) | 0.64 |

| 4 h after ERCP | 0.75 (2.5) | 0.68 (1.0) | 0.81 |

| 24 h after ERCP | 0.62 (2.3) | 0.82 (1.0) | 0.33 |

| Hyperamylasemia2 24 h after ERCP, number (%) | 8 (24) | 4 (13) | 0.53 |

| Missing data | 5 (13) | 6 (16) | |

| Lipase (microkat/L), median, (interquartile range) | |||

| At baseline | 0.53 (0.3) | 0.48 (0.5) | 0.47 |

| 4 h after ERCP | 1.02 (5.9) | 0.76 (1.4) | 0.47 |

| 24 h after ERCP | 0.77 (1.1) | 1.07 (1.5) | 0.62 |

| Hyperlipasemia2 24 h after ERCP, number (%) | 8 (21) | 7 (18) | 0.89 |

| Missing data | 5 (13) | 7 (18) | |

| Hyperenzymemia3 24 h after ERCP, number (%) | 9 (24) | 7 (18) | 0.51 |

| Missing data | 4 (11) | 3 (8) | |

| Abdominal pain 24 h after ERCP, number (%) | 8 (23) | 9 (26) | 0.93 |

| Missing data | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | |

| Acute pancreatitis (hyperenzymemia and abdominal pain after 24 h), number (%) | 5 (13) | 4 (11) | 0.57 |

| Missing data | 7 (18) | 4 (11) | |

1In all analyses missing values were included as a separate category; P-values refer to overall differences between groups;

Defined as 3 times higher than the normal reference value;

Occurrence of hyperamylasemia or hyperlipasemia. ECRP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

The evaluation of the effect of missing outcome data using the enzyme levels 4 h after ERCP in patients with missing 24-h values did not change the main results (data not shown). Acute pancreatitis occurred in 5 patients in the losartan group and 4 in the placebo group (P = 0.57) (Table 3). All cases of pancreatitis were mild as defined according to the Atlanta criteria[41]. Among the cases of pancreatitis the losartan treated group had more difficult cannulations compared to the placebo group, while there was no difference regarding degree of contrast filling.

DISCUSSION

This study provided no support for the hypothesis that losartan has a protective effect against the development of pancreatic hyperenzymemia after ERCP.

The randomized design, the blinding of all patients, clinical staff and evaluators, the use of identical capsules for losartan and placebo, and the objective outcome measurement, i.e., assessment for predefined pancreatic enzyme levels 24 h after the intervention, are among the strengths of the study. There are, however, several weaknesses to consider. The large number of patients found not to be eligible for inclusion extended the study period. The limited sample size meant that it was not possible to detect weak associations, which meant that type 2 errors could have occurred. The sample size estimation was, however, deliberately carried out with the purpose of detecting a strong decrease in hyperenzymemia only. Despite the randomization, the limited sample size could have introduced confounding if important covariates were not evenly distributed between the comparison groups. The distribution of the evaluated potential confounding factors was, however, fairly equal. Moreover, to avoid confounding due to any remaining imbalances, we analyzed the data using multivariable regression with adjustment for several covariates. Hyperenzymemia was used as a surrogate marker for increased risk of acute post-ERCP pancreatitis. This was justified by the strong link between these conditions[42]; further, hyperenzymemia has previously been used as a marker for pancreatic damage and pancreatitis after ERCP[1,16,26,27]. Since the occurrence of hyperenzymemia is markedly more common than pancreatitis, such a surrogate marker provided an opportunity to have a more limited sample size. If the results of the present study had indicated a prophylactic effect of losartan on hyperenzymemia, we had intended to expand the study to comprise a sufficient number of patients to address the outcome acute pancreatitis. The rate of post-ERCP pancreatitis was somewhat higher than expected, partly due to detection bias. Also, the study is small and therefore the high reported incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis could be due to chance.

Experimental and clinical findings suggest that ARB’s will protect against development of acute pancreatitis[31-33,35], but our study did not support this hypothesis. Apart from a true lack of effect, our negative results could have been due to several other factors: The tested dose (50 mg) of losartan might have been too low to have any preventive effect, and earlier administration of losartan could have been more beneficial, since a peak plasma concentration is obtained 4-6 h after an oral dose. The dose was predefined, however, and chosen on the basis of an experimental report of a protective effect on cerulein induced acute pancreatitis using 0.2 mg/kg in rats[32]. Moreover, losartan did decrease the blood pressure, suggesting that the dosage was at least sufficient to affect peripheral vasoconstriction. To date, the tissue concentration of losartan in the pancreas remains unknown. Thus, the study hypothesis cannot be dismissed on the basis of the present trial only. Before considering another randomized trial, e.g., with a longer pre-treatment latency and a higher dose of ARB, we suggest further observational investigations of the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis among ARB users.

In conclusion, one oral capsule of 50 mg of the ARB losartan given one hour before ERCP did not prevent pancreatic hyperenzymemia after the ERCP procedure in this randomized, blinded and placebo-controlled clinical trial.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Eja Fridsta contributed to building the study database and designed the case reports form. Neither of the funding bodies influenced the scientific content of the study.

COMMENTS

Background

This experimental randomized trial based on experimental research, which have shown beneficial effects on pancreatitis using angiotensin receptor blockers. Also, clinical evidence exists from an epidemiological study showing reduced risk of acute pancreatitis in hypertensive patients in a primary care setting in United Kingdom. Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography is usually successful, e.g., removing gallstones and accessing bile ducts for other therapeutic purposes. However, there exist a small risk of the potential lethal complication of acute pancreatitis. This is the reason they are investigating the potential lowering risk of losartan on the risk of development of hyperenzymemia.

Research frontiers

Many different approaches both pharmacological and intervention-related have been tried to reduce the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis. Promising results have been seen pharmacologically with drugs, e.g., gabexate and ulinastatin, and with increased use of pancreatic stenting have also been successful in some studies. Still the need for better prophylactic strategies is large to reduce a potential life-threatening complication like pancreatitis.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In general, losartan, which belongs to the pharmacological class of angiotensin receptor blockers, are used broadly to treat high blood pressure, and heart failure. Experimentally, a role for angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) is suggested in conditions such as inflammation, and cancer. Previously, experimental animal research have tested ARB on pancreatic inflammation with promising results, but the authors aimed to investigate this in humans, with the effect on pancreatic enzymatic secretion, in turn potentially leading to pancreatic inflammation.

Applications

This study suggests no benefit of losartan on the development of hyperenzymemia after ERCP. However, due to limited sample size, larger well-designed controlled trials could evaluate this question further to rule out an unseen effect so far.

Terminology

Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography is an investigation using a flexible endoscope accessing the bile ducts allowing both therapeutic and diagnostic interventions. Losartan is anti-hypertensive drug acting on the renin-angiotensin system, which has effects on blood pressure, inflammation and salt balance.

Peer review

This is a well-designed randomized double-blind study, which examines the effect of the well-known anti-hypertensive drugs. Advantages include the strict randomized design, the identical capsules used for placebo and active drugs, objective outcome measurement using pancreatic enzymes, and strict adherence to intention-to-treat principle while analyzing the results. Disadvantages include sample-size, because a larger study would make the results more reliable and also possible to analyze the effect on acute pancreatitis, rather than the proxy variable hyperenzymemia.

Footnotes

Supported by The Swedish Society of Medicine, The Lisa and Johan Grönberg Foundation

Peer reviewers: Mohammad Al-Haddad, MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, Director, Endoscopic Ultrasound Fellowship Program, Indiana University School of Medicine, 550 N. University Blvd, Suite 4100, Indianapolis, IN 46202, United States; Viktor Ernst Eysselein, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, 1000 W. Carson Street, Box 483, Torrance, CA 90509, United States

S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Tsujino T, Komatsu Y, Isayama H, Hirano K, Sasahira N, Yamamoto N, Toda N, Ito Y, Nakai Y, Tada M, et al. Ulinastatin for pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:376–383. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00671-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoo JW, Ryu JK, Lee SH, Woo SM, Park JK, Yoon WJ, Lee JK, Lee KH, Hwang JH, Kim YT, et al. Preventive effects of ulinastatin on post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in high-risk patients: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pancreas. 2008;37:366–370. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31817f528f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotton PB, Garrow DA, Gallagher J, Romagnuolo J. Risk factors for complications after ERCP: a multivariate analysis of 11,497 procedures over 12 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman ML. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: patient and technique-related risk factors. JOP. 2002;3:169–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andriulli A, Leandro G, Federici T, Ippolito A, Forlano R, Iacobellis A, Annese V. Prophylactic administration of somatostatin or gabexate does not prevent pancreatitis after ERCP: an updated meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng M, Bai J, Yuan B, Lin F, You J, Lu M, Gong Y, Chen Y. Meta-analysis of prophylactic corticosteroid use in post-ERCP pancreatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poon RT, Yeung C, Liu CL, Lam CM, Yuen WK, Lo CM, Tang A, Fan ST. Intravenous bolus somatostatin after diagnostic cholangiopancreatography reduces the incidence of pancreatitis associated with therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedures: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2003;52:1768–1773. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poon RT, Yeung C, Lo CM, Yuen WK, Liu CL, Fan ST. Prophylactic effect of somatostatin on post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:593–598. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70387-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arcidiacono R, Gambitta P, Rossi A, Grosso C, Bini M, Zanasi G. The use of a long-acting somatostatin analogue (octreotide) for prophylaxis of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Endoscopy. 1994;26:715–718. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kisli E, Baser M, Aydin M, Guler O. The role of octreotide versus placebo in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:250–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li ZS, Pan X, Zhang WJ, Gong B, Zhi FC, Guo XG, Li PM, Fan ZN, Sun WS, Shen YZ, et al. Effect of octreotide administration in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis and hyperamylasemia: A multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomopoulos KC, Pagoni NA, Vagenas KA, Margaritis VG, Theocharis GI, Nikolopoulou VN. Twenty-four hour prophylaxis with increased dosage of octreotide reduces the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang FY, Guo WS, Liao TM, Lee SD. A randomized study comparing glucagon and hyoscine N-butyl bromide before endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:283–286. doi: 10.3109/00365529509093278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silvis SE, Vennes JA. The role of glucagon in endoscopic cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1975;21:162–163. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(75)73837-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavallini G, Tittobello A, Frulloni L, Masci E, Mariana A, Di Francesco V. Gabexate for the prevention of pancreatic damage related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gabexate in digestive endoscopy--Italian Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:919–923. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masci E, Cavallini G, Mariani A, Frulloni L, Testoni PA, Curioni S, Tittobello A, Uomo G, Costamagna G, Zambelli S, et al. Comparison of two dosing regimens of gabexate in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2182–2186. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueki T, Otani K, Kawamoto K, Shimizu A, Fujimura N, Sakaguchi S, Matsui T. Comparison between ulinastatin and gabexate mesylate for the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a prospective, randomized trial. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1986-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng M, Chen Y, Yang X, Li J, Zhang Y, Zeng Q. Gabexate in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brust R, Thomson AB, Wensel RH, Sherbaniuk RW, Costopoulos L. Pancreatic injury following ERCP. Failure of prophylactic benefit of Trasylol. Gastrointest Endosc. 1977;24:77–79. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(77)73457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujishiro H, Adachi K, Imaoka T, Hashimoto T, Kohge N, Moriyama N, Suetsugu H, Kawashima K, Komazawa Y, Ishimura N, et al. Ulinastatin shows preventive effect on post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in a multicenter prospective randomized study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1065–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabenstein T, Roggenbuck S, Framke B, Martus P, Fischer B, Nusko G, Muehldorfer S, Hochberger J, Ell C, Hahn EG, et al. Complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy: can heparin prevent acute pancreatitis after ERCP? Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:476–483. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.122616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Palma GD, Catanzano C. Use of corticosteriods in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: results of a controlled prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:982–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.999_u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherman S, Blaut U, Watkins JL, Barnett J, Freeman M, Geenen J, Ryan M, Parker H, Frakes JT, Fogel EL, et al. Does prophylactic administration of corticosteroid reduce the risk and severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a randomized, prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:23–29. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray B, Carter R, Imrie C, Evans S, O’Suilleabhain C. Diclofenac reduces the incidence of acute pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1786–1791. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devière J, Le Moine O, Van Laethem JL, Eisendrath P, Ghilain A, Severs N, Cohard M. Interleukin 10 reduces the incidence of pancreatitis after therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:498–505. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moretó M, Zaballa M, Casado I, Merino O, Rueda M, Ramírez K, Urcelay R, Baranda A. Transdermal glyceryl trinitrate for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: A randomized double-blind trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:1–7. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Räty S, Sand J, Pulkkinen M, Matikainen M, Nordback I. Post-ERCP pancreatitis: reduction by routine antibiotics. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:339–345; discussion 345. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenstein RJ, Krakoff LR, Felton K. Activation of the renin system in acute pancreatitis. Am J Med. 1987;82:401–404. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90437-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung PS, Chan WP, Nobiling R. Regulated expression of pancreatic renin-angiotensin system in experimental pancreatitis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;166:121–128. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsang SW, Cheng CH, Leung PS. The role of the pancreatic renin-angiotensin system in acinar digestive enzyme secretion and in acute pancreatitis. Regul Pept. 2004;119:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsang SW, Ip SP, Leung PS. Prophylactic and therapeutic treatments with AT 1 and AT 2 receptor antagonists and their effects on changes in the severity of pancreatitis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:330–339. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oruc N, Ozutemiz O, Nart D, Yuce G, Celik HA, Ilter T. Inhibition of renin-angiotensin system in experimental acute pancreatitis in rats: a new therapeutic target? Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2010;62:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan YC, Leung PS. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-dependent nuclear factor-kappaB activation-mediated proinflammatory actions in a rat model of obstructive acute pancreatitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:10–18. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.124891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sjöberg Bexelius T, García Rodríguez LA, Lindblad M. Use of angiotensin II receptor blockers and the risk of acute pancreatitis: a nested case-control study. Pancreatology. 2009;9:786–792. doi: 10.1159/000225906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dickstein K, Gottlieb S, Fleck E, Kostis J, Levine B, DeKock M, LeJemtel T. Hemodynamic and neurohumoral effects of the angiotensin II antagonist losartan in patients with heart failure. J Hypertens Suppl. 1994;12:S31–S35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gottlieb SS, Dickstein K, Fleck E, Kostis J, Levine TB, LeJemtel T, DeKock M. Hemodynamic and neurohormonal effects of the angiotensin II antagonist losartan in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1993;88:1602–1609. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gottlieb SS Lakemedelsverket. Lakemedelsverkets foreskrifter och allmanna rad om klinisk provning av lakemedel for humant bruk. Lakemedelsverket: Director General Gunnar Alvan; 2003. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 39.European Medical Agency. Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. London: European Medical Agency; 2006. p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 40.European Medical Agency. Guideline on missing data in confirmatory clinical trials. London: European Medical Agency; 2009. p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradley EL. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586–590. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170122019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunicardi CAD, Billiar T, Dunn D, Hunter J, Matthews J, Pollock R. Schwartz's Principles of Surgery. 9th ed. Pancreas: McGraw-Hill; 2009. [Google Scholar]