Abstract

Introduction:

It has been previously reported that ulcerative colitis (UC) could be associated with cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. There is controversy among different studies; however, this study is conducted in Isfahan. We evaluated the frequency distribution of CMV infection in Iranian patients with active UC comparison to normal individuals.

Materials and Methods:

This case-control study was conducted on 22 patients with active UC and 22 age- and sex-matched controls (F: M = 1). Samples were taken from colonoscopic specimens and tested with sensitive primers of the CMV using the polymerase chain reaction method, the most sensitive method for detecting CMV infection.

Results:

Patients and controls were similar in age (35.9 ± 11.03 years in the case and 40.8 ± 11.3 years in the control group) P=0.153. CMV DNA was found in 13.6% of the subjects in each group; therefore, total percentage of CMV infection was 13.6%. Six cases with CMV infection were three males and three females with age of 38.5 ± 11.02 years (compared to 38.3 ± 11.5 years in noninfected subjects P=0.968).

Conclusion:

In our study, Iranian patients with active UC did not have a higher rate of CMV infection than controls.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, polymerase chain reaction, ulcerative colitis

INTRODUCTION

Infection with cytomegalovirus (CMV), a DNA virus of herpersviridae family, is a prevalent viral infection that can be detected in 40–100% of population.[1,2] Often, CMV infection is asymptomatic or induces mononucleosis-like syndrome, but in immunocompromised patients, it may produce symptomatic gastrointestinal diseases such as gastrointestinal mucosal ulcers followed by hemorrhage.[3] Some previous studies noted that ulcerative colitis (UC) could be associated with CMV infection,[1–14] but there is controversy about the role of CMV infection in UC,[7,15] whether CMV infection is a cause of UC or UC is a predisposing factor for CMV infection.[1]

Several predisposing factors for infection are present in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) including the disease process itself, immunosuppressive therapy leading to leukopenia, surgical interventions, malnutrition, and older age.[16] Some case reports are available on UC accompanied with CMV infection, but a few well-designed studies have been performed in this regard.[1,4] Available evidence comes from studies that have focused on CMV markers in urine or blood of the IBD patients, and there are a few molecular studies about detecting CMV DNA in intestinal tissue samples.[4] Few reports are also available detecting CMV genome in IBD patients using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method, the most sensitive method for detecting CMV infection.[14] Considering the importance of knowledge about the association of CMV infection and IBD and regarding the lack of data, the aim of this study was to evaluate the frequency distribution of CMV infection in Iranian patients with active UC using sensitive diagnostic tests.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting and patients

This case-control study was conducted on 22 patients with active UC and 22 age- and sex-matched controls (F: M = 1) from march 2010 to 2011 in Isfahan, Iran. UC was diagnosed based on the clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic studies. In the UC patients, the disease activity was assessed with the Mayo Disease Activity Index and patients with scores of >2 were considered as in active phase of the disease.[17] Subjects in the control group were included from those who referred with gastrointestinal symptoms, but have a normal colonoscopy and histopathologic results.

CMV investigation

Samples were consisted of formalin fixed paraffin embedded blocks from colonoscopic specimens. The DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the recommended protocol. Then, extracted DNA amplified by the PCR method. The reaction mixture of the PCR was contained: 2.5 μM mgcl2, 0.25 μM of each primers, 0.2 μM of each dNTPs, 0.25 unit/25 μL Tag DNA polymerase, 1X PCR buffer (20 μM Tris- Hcl PH 8.6, 50 μM kcl) and 100 ng template DNA in 25 μL final volume. The PCR mixtures were subjected to amplification at: 95°C 5 min (pre-denaturation), 94°C 50s, 58°C 1 min, 72°C 1 min for 35 cycles and 72°C 5 min (final extension).[18]

In this study, a 406 bp fragment from the Hind III-X fragment of CMV genome was amplified by using two primers. The sequence of forward and reverse primer was 5’-GGA TCC GCA TGG CAT TCA CGT ATG T-3’, 5’-GAA TTC AGT GGA TAA CCT GCG GCG A-3’, respectively.[14,18] These primers have been previously recognized to be very sensitive (94% in symptomatic infection).[14] Positive control consisted of a block of colon biopsy with documented CMV genome as well as negative control, were included in each run of PCR. Then, PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel, stain with ethidium bromide and then were visualized by UV light. Visualization of a 406 bp amplicon defined as positive for CMV DNA.

Data were analyzed with the SPSS software for windows version 16.0 using the chi-square and fisher's exact tests for qualitative and independent t-test for continuous variables.

RESULTS

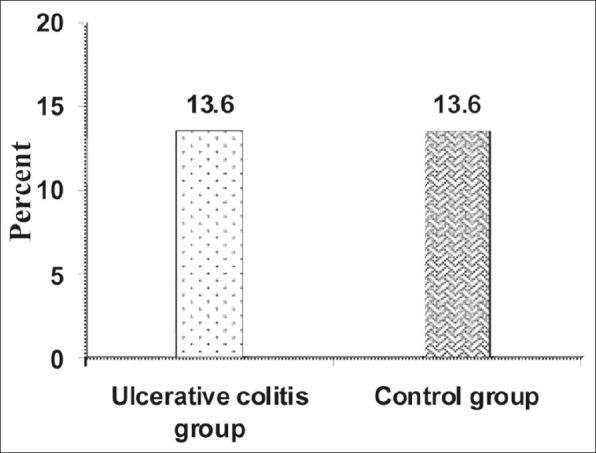

Patients and controls were similar in age (35.9 ± 11.03 years in the case and 40.8 ± 11.3 years in the control group); P=0.153. CMV DNA was found in 13.6% (3/22) of the subjects each group; P=1 [Figure 1]. 3 out of 22 females (13.6%) and also, 3 out of 22 males (13.6%) were CMV positive; P=1. The mean age of CMV positive cases was 38.5 ± 11.02 years comparison to noninfected subjects with mean age 38.3 ± 11.5 years; P=0.968.

Figure 1.

Rate of CMV infection in both groups (P value=1)

DISCUSSION

Since 1961, several studies have showed a relationship between CMV infection and UC.[1] Our experience revealed that there was no significant difference in the frequency distribution of CMV infection between patients with UC and controls. Also, we did not find any correlation between CMV infection and age or sex. These results are in agreement with Lavagna et al. study on colonic specimens from 24 refractory UC patients and 20 controls (colorectal cancer patients). Authors have reported that there was no significant difference between the two groups for CMV infection and suggested that CMV infection is uncommon, despite using PCR that considered to be a highly sensitive method.[19] However, another study by Dimitroulia et al. on 85 IBD patients (58 UC and 27 Crohn's disease) and 42 controls with non inflammatory disease showed that CMV genome in blood and intestinal samples of UC patients was significantly higher than controls.[4] Also, Mariguela et al. studied 14 colorectal cancer and 21 UC patients and showed that UC patients had significantly higher frequency of CMV comparison to colorectal cancer patients.[1]

Reports from previous studies revealed different prevalence rates of active CMV (0.53–36%) in IBD patients.[14] One of the factors that can be related to different results of the studies is the local prevalence of CMV infection. The prevalence of CMV infection is different among countries and even various locations of a country.[19] Prevalence of CMV can be related to the studied patient population and also to prior treatment used.[14] In some studies, cases were collected from UC patients who were refractory to steroid or immunosuppressive therapies. The study by Domenech et al. in patients with UC showed that CMV infection was found in steroid-refractory patients, but not in those who responded to the steroids and those with inactive disease.[8] Higher prevalences of CMV infection in steroid–refractory UC patients have also been reported by Ayre et al.,[6] and Maher et al. studies.[7] In Ayre et al. study, they detected CMV in colonic mucosa of 5–36% steroid-resistant patients and 0–10% patients who responded to the steroid.[6] Maher et al. study was done on 72 active IBD patients of which 23 were steroid-resistant.CMV was found in 8 of 23 steroid-resistant and 1 patient in remaining 31 patients under steroid therapy.[7]

Other factor that may influence the prevalence of CMV among IBD patients is the specimen type.[14] In study by Maconi et al. on 77 UC patients using surgical and preoperative biopsy specimens, CMV was detected in 21% of surgical and 8% of biopsy specimens. They concluded that biopsy specimens can miss CMV infection.[13]

CONCLUSION

In this study, we observed that active UC patients do not have a significant higher rate of CMV infection than controls.

Contribution

MM carried out the design and coordinated the study and helped in writing the manuscript. HT provided advisor for design of the study and helped in writing the manuscript. AR carried out the experiments and gathered the data and wrote the manuscript. RD helped in performing the experiments.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mariguela VC, Chacha SG, Cunha Ade A, Troncon LE, Zucoloto S, Figueiredo LT. Cytomegalovirus in colorectal cancer and idiopathic ulcerative colitis. Rev Inst Med Trop sao Paulo. 2008;50:83–7. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652008000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herfath HH, long MD, Rubinas TC, Sandridge M, Miller MB. Evaluation of a non- invasive method to detect cytomegalovirus (CMV) – DNA in stool samples of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1053–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1146-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minami M, Ohta M, Ohkura T, Ando T, Ohmiya N, Niwa Y, et al. cytomegalovirus infection in severe ulcerative colitis patients undergoing continuous intravenous cyclosporine treatment in japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:754–60. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i5.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimitroulia E, Spanakis N, Konstantinidou AE, Legakis NJ, Tsakris A. frequent detection of cytomegalovirus in the intestine of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:879–84. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000231576.11678.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshino T, Nakase H, Ueno S, Uza N, Inoue S, Mikami S, et al. usefulness of quantitative real- time PCR assay for early detection of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with ulcerative colitis refractory to immunosuppressive therapies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1516–21. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayre K, warren BF, Jeffery K, Travis SP. The role of CMV in steroid- resistant ulcerative colitis: A systematic Review. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maher MM, Nassar MI. Acute cytomegalovirus infection is a risk factor in refractory and complicated inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2456–62. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domenech E, Vega R, Ojanguren I, Hernandez A, Garcia-Planella E, Bernal I, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in ulcerative colitis: A prospective, comparative study on prevalence and diagnostic strategy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1373–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuwabara A, Okamoto H, Suda T, Ajioka Y, Hata keyama K. Clinicopathologic characteristics of clinically relevant cytomegalovirus infection in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:823–9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arevalo Suarez F, Cerrilo Sanchez G, Sandoval Compos J. cytomegalovirus in ulcerative colitis in Hospital Nacional 2 de Mayo. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2007;27:150–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pofelski J, Heluwaert F, Roblin X, Morand P, Gratacap B, Germain E, et al. Cytomegalovirus and cryptogenic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2007;31:292–6. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(07)89376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandiel A, Lashner B. Cytomegalovirus colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2857–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maconi G, Colombo E, Zerbi P, Sampietro GM, Fociani P, Bosani M, et al. prevalence, detection rate and outcome of cytomegalovirus infection in ulcerative colitis patients requiring colonic resection. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:418–23. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kishore J, Ghoshal U, Ghoshal UC, Krishnani N, Kumar S, Singh M, et al. Infection with cytomegalovirus in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Prevalence, clinical significance and outcome. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:1155–60. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baroco Al, Oldfield EC. Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease in the immunocompromised patient. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:409–16. doi: 10.1007/s11894-008-0077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epple HJ. Therapy and non-therapy– dependent infectious complications in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2009;27:555–9. doi: 10.1159/000233297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis JD, Lichtenstein GR, Deren JJ, Sands BE, Hanauer SB, Katz JA, et al. Rosiglitazone for active ulcerative colitis: A randomized placebo- controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:688–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amini Bavil Olyaee S, Sabahi F, Karimi M. PCR optimization: Improving of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) PCR to achieve a highly sensitive detection method. Iran J Biotechnol. 2003;1:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavagna A, Bergallo M, Dapermo M, Sostegni R, Ravarino N, Crocella L, et al. The hazardous burden of Herpesviridae in inflammatory bowel disease: The case of refractory severe ulcerative colitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:887–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]