Abstract

Background:

There is uncertainty as to whether addition of magnesium sulfate to spinal local anesthetics improves quality and duration of block in the caesarean section. In this randomized double blind clinical trial study, we investigated the effect of adding different doses of intrathecal magnesium sulfate to bupivacaine in the caesarean section.

Materials and Methods:

After institutional approval and obtaining informed patient consent, 132 ASA physical status I-II women undergoing elective cesarean section with spinal anesthesia were randomized to four groups: 1 – 2.5 cc Bupivacaine 0.5%+ 0.2 cc normal saline (group C) 2 – 2.5 cc Bupivacaine 0.5%+ 0.1 cc normal saline+ 0.1 cc magnesium sulfate 50% (group M50) 3– 2.5 cc Bupivacaine 0.5%+ 0.05 cc normal saline+ 0.15 cc magnesium sulfate 50% (group M75) 4– 2.5 cc Bupivacaine 0.5%+ 0.2 cc magnesium sulfate 50% (group M100). Patients and staff involved in data collections were unaware of the patient group assignment. We recorded the following: onset and duration of block, time to complete motor block recovery, and analgesic requirement.

Results:

Magnesium sulfate caused a delay in the onset of both sensory and motor blockade. The duration of sensory and motor block were longer in M75 and M100 groups than group C (P < 0.001). Recovery time was shorter in group C (P < 0.001) and analgesic requirement was more in group C than others (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

In patients undergoing the caesarean section under hyperbaric bupivacaine spinal anesthesia, the addition of 50, 75, or 100 mg magnesium sulfate provides safe and effective anesthesia, but 75 mg of this drug was enough to lead a significant delay in the onset of both sensory and motor blockade, and prolonged the duration of sensory and motor blockade, without increasing major side effects.

Keywords: ASA, bupivacaine, caesarean section magnesium sulfate, local anesthetics, spinal anesthesia

INTRODUCTION

Spinal anesthesia is commonly used for the cesarean section because of avoiding the risks of general anesthesia, allowing a parturient to remain awake and enjoy the birthing experience.[1] The quality and duration of sensory and motor block and decrease post operative pain is important in the caesarean section and patient's content satisfaction. Opioids and other drug such as clonidine and neostigmine added to local anesthetics to this purpose, but significant side effects, such as pruritus, respiratory depression, nausea, and vomiting may limit their use.[2] Central sensitization is an activity-dependent increase in the excitability of spinal neurons and is considered to be one of the mechanisms implicated in the persistence of postoperative pain.[3]

Magnesium sulfate block the N- methyle –D- aspartate (NMDA) channels in a voltage-dependent way to be improve the quality and duration of spinal block.[4] However, the use of magnesium sulfate safety profile has been documented by histopathological analysis in experimental studies.[5] Systemic delivery of magnesium sulfate decrease postoperative opioid requirements.[6,7] In experimental studies, spinal injection of magnesium sulfate reduces the respond to painful stimulus in rats.[8] Magnesium sulfate ordered together with fentanyl in other surgeries with different doses in spinal anesthesia (in human) and delivery painless, but there are no enough studies for the caesarean section.[9]

In one study, the addition of 50 mg intrathecal magnesium sulfate to spinal anesthesia was not desirable in patients undergoing knee arthroscopy.[3] In another previous trials, 100 mg intrathecal magnesium sulfate prolonged the duration of sensory block.[10,11] However, according to our knowledge, no previous study has clearly investigated the effect of different doses of this drug for spinal anesthesia in the caesarean section.

Due to physiologic changes in pregnancy, it may be necessary to adjust the dose of magnesium sulfate such as other drugs in caesarean section surgery.

This prospective randomized double blind clinical study was designed to evaluate different intrathecal doses of magnesium sulfate in parturients undergoing the elective caesarean section.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Following ethics committee approval and informed patient consent, 132 ASA physical status I or II, at term and 18–45-year-old women undergoing elective caesarean section surgery were recruited. This study was performed in the Beheshti Medical Center, Isfahan, Iran, during the period from March 2010 to December 2011.

Exclusion criteria were significant coexisting, hepatorenal, or other end organ disease, twin or complicated pregnancy, obesity (BMI > 38 kg/m2), contraindication to regional anesthesia and sensitivity to local anesthetic drugs.

The operating theatre nurse assistant used randomization protocol to assign participants to their respective groups, and an independent anesthesiologist, who did not participate in the study or data collection, prepared unlabelled syringes containing the study drugs.

All patients were fasted for 8 h preoperatively and infused intravenous preload of 10 cc/kg Ringer's lactate solution before surgery.

Intraoperative monitoring included pulse oximetry, automated blood pressure cuff, lead II electrocardiogram and capnograph.

The patients were randomly allocated to one of four groups of 33 each.

Groups C: the control group received 12.5 mg (2.5 mL) of hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% with 0 .2 mL normal saline without preservative.

Groups M50: received 12.5 mg (2.5 mL) hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% with 50 mg (0.1 mL) magnesium sulfate 50% added to 0.1 mL normal saline without preservative.

Group M75: received 12.5 mg (2.5 mL) hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% with 75 mg (0.15 mL) magnesium sulfate 50% added to 0.05 cc normal saline without preservative.

Group M100: received 12.5 mg (2.5 mL) hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% with 100 mg (0.2 mL) magnesium sulfate 50%.

Subjects were allocated study groups by the computer-generated random number assignment. Both patient and anesthetist were blind to treatment.

Lumbar puncture was performed in the sitting position. A 25 gauge (pencil point, Braun, Melsungen, Germany) spinal needle was introduced into the subarachnoid space at the L3–L4 lumber level midline approach with the needle orifice cephalad. Cerebrospinal fluid was aspirated and the ready fluid hyperbaric bupivacaine (Mylan Co, France) added with magnesium sulfate was injected to subarachnoid space over the period of 15 s, with no barbotage. Patient was set to the left lateral position and after the establishment of T6 block with pin prick test and confirmation of anesthesia, the cesarean section was done.

The study solution prepared by another researcher was not involve in patient care, and then injected immediately afterwards. The spinal needle was withdrawn and patients were repositioned supine with elevation of head (15°–20°). No additional analgesic was administered unless requested by the patient.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP, DBP), heart rate (HR), level of consciousness recorded in the base line and every 15 min. Newborn apgar score checked 1 and 5 min after birth recorded by a anesthetist blinded to the patient groups.

The onset and duration of sensory block, recovery, and duration of spinal anesthesia were also recorded.

The onset of sensory block was defined as the time between injection of the intrathecal anesthetic and the absent of pain at T6 dermatome, assessed by the pin prink test.

Motor block was assessed by the modified bromage score (0: no motorless, 1: inability to flex the hip, 2: inability to flex the knee, 3: inability to flex ankle). Complete motor block recovery was assumed when the modified bromage score was 0. The duration of spinal anesthesia was defined as the period from spinal injection to the first occasion when the patient complained of pain in the postoperative period.

If SBP was<20% below baseline or <100 mmHg, intravenous (IV) ephedrine 5 mg was given incrementally. If the heart rate was less than 50 beats/min 0.5 mg atropine sulfate was administered IV. The incidence of hypotension (mean arterial pressure <20% of baseline), bradycardia (HR<50 beats/min), hypoxemia, excessive sedation, nausea, and vomiting was recorded.

Patients were discharged from the recovery room when the motor block was completely resolved. The discharge criteria for the ward were stable signs (no pains, no nausea and vomiting). Patients were also assessed for the presence of motor or sensory complication on the day after surgery.

Power analysis showed that with power of 0.8 and significance level of 0.05, 33 subject per study group were required. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS 10. Demographic (sex, age, weight, height) and clinical characteristics (onset time, Motor blockade , and time on first analgesic requirement), sedation scores, the incidence of intra- and postoperative adverse events were analyzed with chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis. Value of P<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

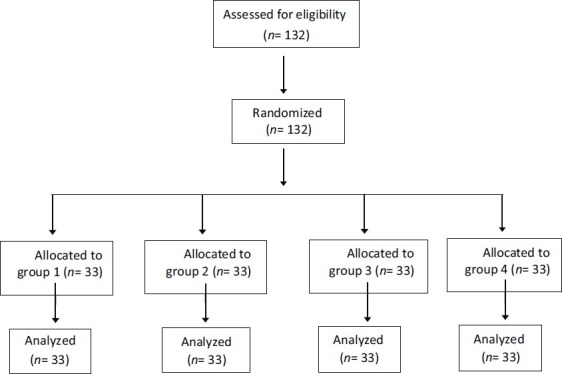

One hundred and thirty two patients completed the study protocol (n=33 in each group) [Figure 1]. The demographic variables of the patients are shown in the Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of enrolled study patients. There was no significant difference among the groups with respect to patient characteristics, age, height, weight, gestational age, and duration of surgery

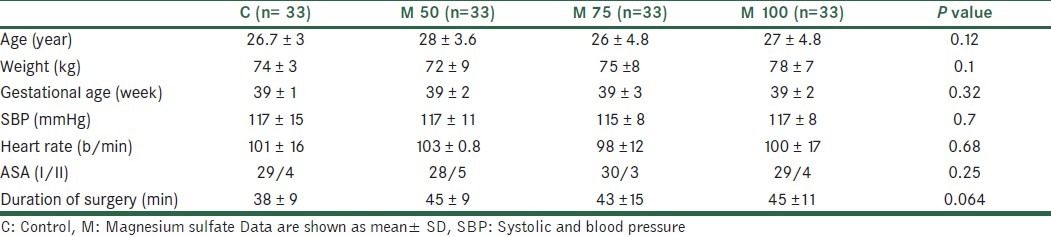

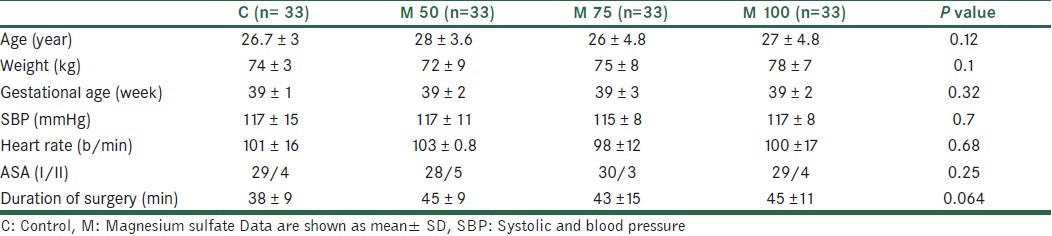

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of parturients (mean ± SD)

There was no significant difference among the groups with respect to patient characteristics, age, height, weight, gestational age, and duration of surgery.

There were differences among groups in the onset time of sensory and motor block, time of resolution of sensory, motor blocks, and recovery time [Table 2].

Table 2.

Characteristics of spinal block (mean ± SD)

Onset time of sensory and motor block was shorter in groups C and M50 than others (P <0.001). Resolution of sensory and motor block was significant longer in M75 and M100 groups than others (P <0.001).

Recovery time was longer in M100 group (65 min) compare with C group (49 min) (P value <0.001).

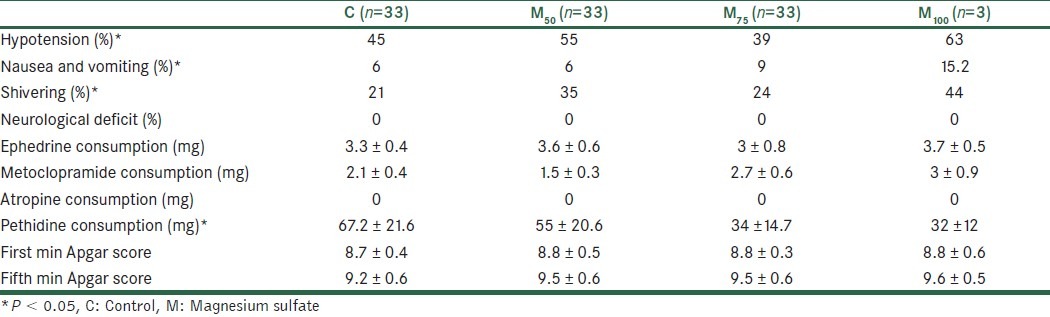

The frequency of Side effects (%), mean drug consumptions (mg) and Apgar scores (mean ± SD) between four groups have shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The frequency of Side effects (%), mean drug consumptions (mg) and Apgar scores (mean ± SD) between four groups

The frequency of complications of intraoperative (hypotension, nausea, and vomiting) was more in M100 group. Hypotension was lower in M75 group (39%) and higher in M100 (63%).

Nausea and vomiting was higher in M100 group (15.2%) and lower in C and M50 groups (6%) [Table 3].

Postoperative complications (hypotension, shivering, nausea. and vomiting) were higher in M100 group and lower in C and M75 groups (P = 0.002) [Table 3]. Respiratory parameters (O2 saturation), puels rate, and temperature value were stable during the perioperative period.

There were no significant difference between the groups with respect to sedation score all the times (P > 0.05).

Perioperative supplemental drugs (ephedrine, metoclopramide, and atropine) requirements had no significant difference between groups.

Apgar score at first and fifth min had no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.84, P = 0.05).

There was a significant difference about Pethidine consumption (mg). It was higher in group C and M50 compared with M100 (P < 0.001).

No neurological deficit or other major complication was observed in any patient receiving magnesium sulfate or saline in the first postoperative week after surgery.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was that in patients undergoing the caesarean section under hyperbaric bupivacaine spinal anesthesia, the addition of 50, 75, or 100 mg magnesium sulfate 50% led to a significant delay in the onset of both sensory and motor blockade, and prolonged the duration of sensory and motor blockade without increasing major side effects. But it seemed that this drug was enough and provide effective anesthesia [Table 2].

In this study, the onset of the sensory and motor block was slower it the M75 and M100 groups than in the M50 and C groups [Table 2]. This finding is similar to previous study in which it has been shown that the addition of intrathecal magnesium sulfate to bupivacaine and fentanyl anesthesia delayed the onset of the sensory and motor blockade but also prolonged the period of anesthesia without additional side effects.[12] It is possible that the solution to which magnesium sulfate was added had a different pH, which might describe our findings. However, we cannot suggest a satisfactory explanation for this delay and further studies and clinical trial are required.

We found that the median duration of sensory and motor blockade was significantly prolonged by 75 mg magnesium sulfate 50% to 124 ± 12 min and 110 ± 80 min and by 100 mg magnesium sulfate 50% to 129 ± 21 min and 111 ± 14 min compared with 92 ± 10 and 98 ± 11 min in group M50 and 96 ± 13 min and 91 ± 12 in group C respectively [Table 2].

Magnesium prolongs the duration of spinal anesthesia, given during labor.[9] This drug is the analgesic and antinociceptive additive drug. When it used with local anesthetic, it resulted in prolongation of analgesia without significant complication.[13] This prolongation of anesthesia is consistent with the experimental synergistic interaction between spinal local anesthetics and NMDA antagonists, like magnesium, which use antinociceptive effects via different mechanisms; hence, the rationale for combining the two. The NMDA receptor channel complex includes binding sites for noncompetitive antagonists such as magnesium sulfate and ketamine. Activation of C-fibers leads to neuronal excitation, which is decreased by NMDA receptor antagonists; hence, the use of magnesium such as an additive drug for spinal block.[14] It acts as an antagonist at a theca NMDA receptor; NMDA receptor antagonists can prevent central sensitization due to peripheral nociceptive stimulation, and can revoke such hypersensitivity once it is established.[4]

The dose of magnesium used in this study was based on data from Buvanendran et al.[9] where 50 mg of spinal magnesium sulfate potentiated fentanyl antinociception. Larger doses have also been used. In 1985, Lejuste[13] described the inadvertent intrathecal injection of 1000 mg of magnesium sulfate, producing a dense motor block followed by complete resolution within 90 min, with no neurological deficit at long-term follow up. Further examination is required to determine whether larger doses of magnesium produce greater potentiation of spinal analgesia without causing any neurological deficit when injected intrathecally.

The efficacy and safety of intrathecal magnesium sulfate reported in rats and human in earlier studies.[8,15] In rats, boluses of magnesium sulfate produced transient motor and sensory block with no opposed clinical or histological results. In a randomized, controlled canine study, no neurological deficit or change in cord histopathology was reported following interathecal magnesium administration (45–60 mg).[16] A recent human study found no harmful effects of IT magnesium on spinal opioid analgesia in labor.[9] Thus, interathecal magnesium sulfate seems to have a good safety profile.

In this study, higher dose (100 mg) of magnesium sulfate might result in increasing some of side effects (hypotention, nausea, and vomiting).

These patients needed to use supplemental drug such as ephedrine or metoclopramide.

Hypotension is a common side effect due to compress vena cava vein by pregnant uterus. Also, it can be caused by sympathectomy of spinal block.

Nausea and vomiting are frequent side effects during the caesarean section due to uterine manipulation and peritoneal closure.[17]

An increased risk of respiratory depression in labor has been reported with magnesium sulfate therapy,[18] and an increased incidence of respiratory depression may be expected when other drugs are combined; however, we did not observe this.

Total analgesic requirements for 24 h following surgery were lower than in patient received higher dose of intrathecal magnesium sulfate (P < 0.001). It is likely that magnesium sulfate can potentiate opioid analgesic effect by both central and peripheral mechanism.[19]

Compared to published data and from the clinical point, the 100 mg magnesium sulfate 50% used in our study does not seem to have more desirable effect than 75 and 50 mg. Although 75 mg magnesium sulfate decrease the postoperative analgesic requirement.

There are several limitations to this study. We did not assess the incidence and intensively of chronic pain after caesarean section surgery that might have revealed the action of magnesium sulfate in modulating wind up and synaptic plasticity.

In conclusion, this randomized double blind clinical study comparing intrathecal magnesium sulfate in different doses of 50, 75, and100 mg with placebo added to hyperbaric bupivacaine for the caesarean section showed all techniques provide safe and effective anesthesia, but 75 mg of this drug increases duration of postoperative analgesia and prolong than sensory and motor block without significant increase in maternal and neonatal side effects.

Authors’ Contributions

Dr. Mitra Jabalameli participated in generating the idea. Both authors designed and conducted the study. Also, they managed the study and prepared the draft of the report then studied and edited the draft and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran (Project No. 83036, IRCT number: IRCT201107112405N8). Authors are thankful to Members of Research Committee of Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for helping in approval processing of this report.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran (Project No. 83036, IRCT number: IRCT201107112405N8).

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yousef AA, Amr YM. The effect of adding magnesium sulphate to epidural bupivacaine and fentanyl in elective Cesarean Section using combined spinal-epidural anesthesia: A prospective double blind randomized study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19:401–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashburn MA, Love G, Pace NL. Respiratory-related critical events with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Clin J Pain. 1994;10:52–6. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dayioglu H, Baykara ZN, Salbes A, Solak M, Toker K. Effects of adding magnesium to bupivacaine and fentanyl for spinal anesthesia in knee arthroscopy. J Anesth. 2009;23:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s00540-008-0677-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ascher P, Nowak L. Electrophysiological studies of NMDA receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1987;10:284–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao WH, Bennet GJ. magnesium suppresses neuropathic pain responses in rat via a spinal site of action. Brain Res. 1994;666:168–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90768-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tramer MR, Schneider J, Marti RA, Rifat K. Role of magnesium sulfate in postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:340–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199602000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz J, Kavanagh BP, Sandler AN, Nierenberg H, Boylan JF, Friedlander M, et al. Preemetive analgesia: Clinical evidence of neuroplasticity contributing to postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:439–46. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroin JS, McCarthy RJ, Von Roenn N, Schwab B, Tuman KJ, Ivankovich AD. Magnesium sulfate potentiates morphine antinociception at the spinal level. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:913–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200004000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buvanendran A, McCarthy RJ, Kroin JS, Leong W, Perry P, Tuman KJ. Intrathecal magnesium prolongs fentanyl analgesia: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:661–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200209000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalili G, Janghorbani M, Sajedi P, Ahmadi G. Effects of adjunct intrathecal magnesium sulfate to bupivacaine for spinal anesthesia: A randomized double-blind trial in patients undergoing lower extremity surgery. J Anesth. 2011;25:892–7. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1227-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghrab BE, Maatoug M, Kallel N, Khemakhem K, Chaari M, Kolsi K, et al. Does Combination of intrathecal magnesium sulfate and morphine improve postcaesarean section analgesia? Ann Fr Anesth Rean. 2009;28:454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arcioni R, Palmisani S, Tigano S, Santorsola C, Sauli V, Romanò S, et al. Combined intrathecal and epidural magnesium sulfate supplementation of spinal anesthesia to reduce post-operative analgesic requirements: A prospective, randomized, double-blinded controlled trial in patients with undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Acta Anesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:482–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lejuste MJ. Inadvertent intrathecal administration of magnesium sulfate. S Afr Med J. 1985;68:367–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickenson AH. NMDA receptor antagonists: Interaction with opioids. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:112–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozalevli M, Cetin TO, Unlugence H. The effect of adding intrathecal magnesium sulphate to bupivacaine-fentanyl spinal anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scan. 2005;49:1514–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson JI, Eide TR, Schiff GA, Clagnaz JF, Hossain I, Tverskoy A, et al. Intrathecal magnesium sulfate protects the spinal cord from ischemic injury during thoracic aortic cross clamping. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:1493–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karaman S, Kocaba M. The Effective of sufentanil or morphine added to hyperbaric bupivacaine in spinal anesthesia for caesarean section. European Journal of Anesthesia. 2006;23:285–91. doi: 10.1017/S0265021505001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witlin AG, Sibai BM. Magnesium sulfate therapy in preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:883–9. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy RJ, Kroin JS, Tuman KJ, Penn RD, Ivankovich AD. Antinociceptive potentiation and attenuation of tolerance by intrathecal co-infusion of magnesium sulfate and morphine in rats. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:830–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]