Abstract

This overview is intended to give a general outline about the basics of Cytopathology. This is a field that is gaining tremendous momentum all over the world due to its speed, accuracy and cost effectiveness. This review will include a brief description about the history of cytology from its inception followed by recent developments. Discussion about the different types of specimens, whether exfoliative or aspiration will be presented with explanation of its rule as a screening and diagnostic test. A brief description of the indications, utilization, sensitivity, specificity, cost effectiveness, speed and accuracy will be carried out. The role that cytopathology plays in early detection of cancer will be emphasized. The ability to provide all types of ancillary studies necessary to make specific diagnosis that will dictate treatment protocols will be demonstrated. A brief description of the general rules of cytomorphology differentiating benign from malignant will be presented. Emphasis on communication between clinicians and pathologist will be underscored. The limitations and potential problems in the form of false positive and false negative will be briefly discussed. Few representative examples will be shown. A brief description of the different techniques in performing fine needle aspirations will be presented. General recommendation for the safest methods and hints to enhance the sensitivity of different sample procurement will be given. It is hoped that this review will benefit all practicing clinicians that may face certain diagnostic challenges requiring the use of cytological material.

Keywords: Cytology, fine needle aspiration

INTRODUCTION

The art and science of cytology and cytopathology has been implemented and recognized as early as the 18th and 19th centuries.[1–5] However the progress and the standardization of this branch of pathology were not founded completely until the late years of the 20th century. The first American Board of Examination in cytopathology was undertaken in 1989. Europeans, especially north Scandinavian countries, were able to utilize this technique even before the World War II.[1,4] The science of cytopathology is currently well standardized with two major branches, exfoliative and aspiration biopsy.

George Papanicolaou, after whom the famous Papanicolaou (Pap) smear and Pap stain was named, was one of the initial pioneers who drove the attention to the science of the ability to make a diagnosis looking at slides with a smear of cells in the period between 1917 and 1928.[1] The initial North American scientific papers describing tumor diagnosis by cytological examination was published in 1930 from New York Memorial Hospital by Drs. Martin and Ellis followed by a publication by Dr. Stewart in 1933.[6,7] After this the scientific and the medical community started paying attention and aggressively pursuing this sub specialized field of pathology.

The first examination of American Board of Cytopathology was held in 1989 after standardization of this branch of pathology.[8] Currently, one-year fellowship of Cytopathology in an accredited program is needed to be eligible for this exam. In addition, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the agency that accredits residency training programs in pathology in the United States of America (USA) currently mandated documentation of fine needle aspiration (FNA) performance training for both residents and cytopathology fellows.[9]

TISSUE BIOPSY VERSUS CYTOLOGICAL MATERIAL

Although there are still few limitations for making the initial diagnosis merely on the basis of cytological material, these limitations are shrinking day by day and the role that cytopathology play as an initial diagnostic tool is currently a standard procedure.[10–16]

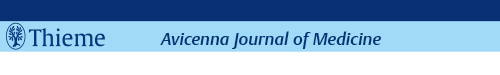

The difference between surgical biopsy and cytopathology material, including fine needle aspiration biopsy is shown in the Table 1. Now, it is well recognized that using cytology including FNA is cost effective, simple, accurate and a safe procedure for making a specific diagnosis that dictates management decisions by the treating clinicians.[17–26]

Table 1.

Comparison between tissue biopsy and fine needle aspiration as a diagnostic tool

UTILIZATION OF CYTOPATHOLOGY

The following are the ultimate objectives from utilization of most cytological specimen and the wide range of diagnostic categories are illustrated in Figures 1–4:

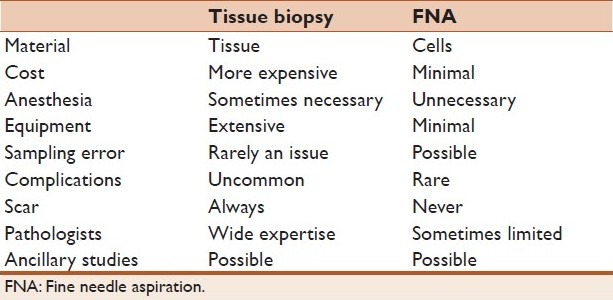

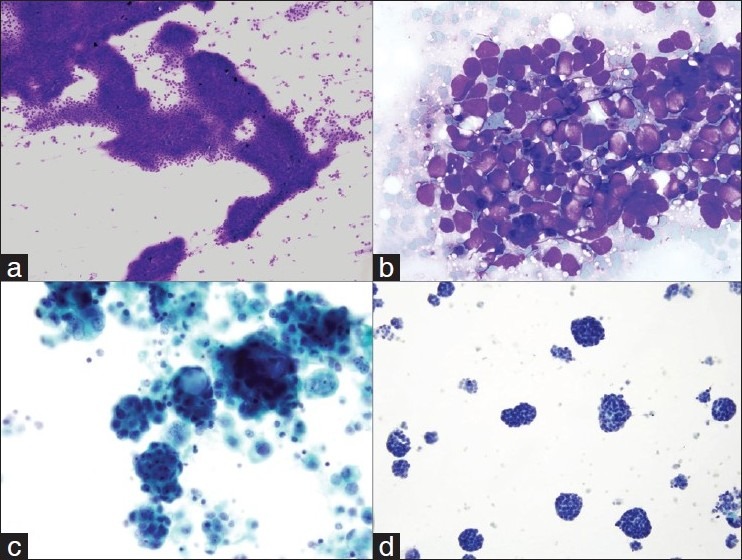

Figure 1.

(a) Aspirate smear of an inguinal lymph node showing poorly formed granuloma with neutrophils. Combining the cytology and serological result, the diagnosis of cat scratch disease was made (Papanicolaou stain, ×400). (b) Bronchoalveolar lavage specimen with Strongyloides in an immunocompromised patient (Papanicolaou stain, ×600). (c) Scrape cytology smear of a non-healing ulcer on the hand of a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. The smear showed fungal hyphae characteristic of Mucor species (Hematoxylin and Eosin, ×400). (d) Bronchoalveolar lavage specimen showing the characteristic “fluffy” clusters of Pneumocystis jiroveci in a patients with AIDS (Papanicolaou stain, ×600).

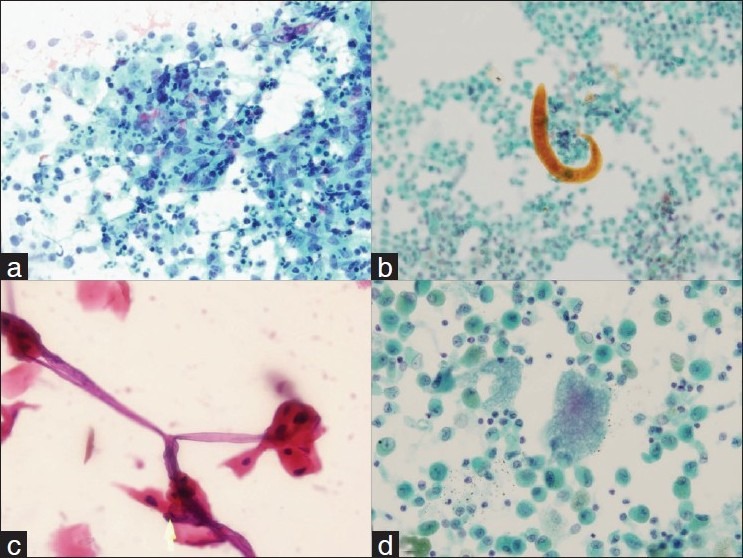

Figure 4.

A case of Hodgkin's lymphoma that was diagnosed by FNA. (a and b) showing the cell block of this case that contains few Reed-Sternberg cells. The cells were immunoreactive for CD 15 (c) and CD 30 (d) and were negative for CD 45 and CD 20, confirming the diagnosis.

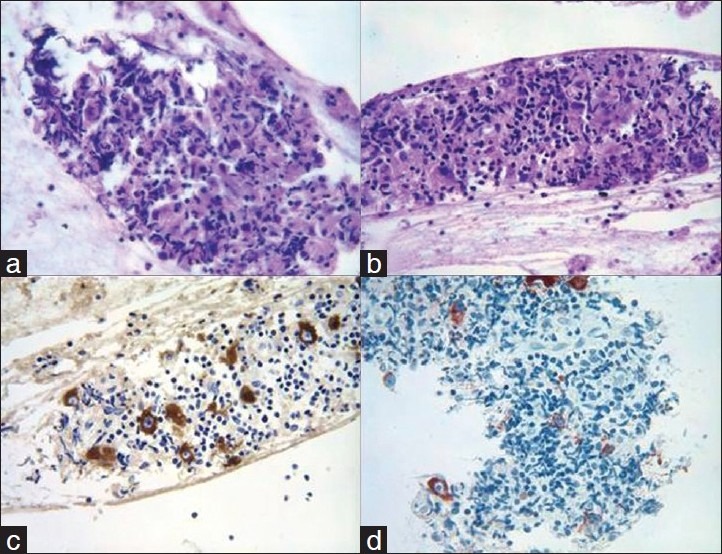

Figure 2.

(a) Low power view of aspirate smear of a solitary liver mass in a patient with chronic history of hepatitis C showing the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (Diff Quik stain, ×100). (b) High power view of metastatic small cell carcinoma to adrenal gland from the lung primary, diagnosis made through computed tomography-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) (Diff Quik stain, ×600). (c) Pleural fluid cytology from a patient with ovarian adenocarcinoma showing the characteristic metastases (Papanicolaou stain, ×600). (d) Pleural fluid cytology from a patient with pleural-based mass diagnosed with mesothelioma. The diagnosis was confirmed by characteristic immunohistochemical stains on pleural fluid material (Papanicolaou stain, ×600).

The optimum goal is to reach a definitive diagnosis

This objective is the ultimate goal. Clinicians, patients, and pathologists are all interested to reach a definitive specific diagnosis utilizing single diagnostic test. It is well recognized now that the utilization of different cytological examinations from different organs provides sufficient diagnostic information that drives treatment decisions.[27–38]

As a screening tool

The success story of utilizing Papanicolaou smears in detecting early precursor lesions of cervical cancer is well known in the developed word. Rates of cancer death due to cervical cancer dropped tremendously after the 1960s when the Papanicolaou smears screening programs had started.[39–43]

As a follow-up for different diseases

Cytological examinations of specimens taken from different sites as a follow-up after establishing the initial diagnosis is a routine procedure. Sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, and bronchial brushings are frequent samples that are used as follow-up for patients with a previous diagnosis of pulmonary carcinoma. Additional common samples that can be used include: pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, discharge samples, cerebrospinal fluid, and FNA from any palpable or non-palpable deep-seated new lesions that appear during the follow-up period.

For determination of different prognostic factors in neoplasia diagnosis

This is usually achieved as part of staging or using the cytological samples to perform ancillary studies, such as Her-2Neu analysis on breast mass aspirates.

ADVANTAGES OF USING CYTOLOGY

The advantages of utilizing cytological examination over traditional tissue are well known, the most important of which are:

Safe

The procedures that are used to get cytological samples are extremely safe. Complications are very rare and when they occur they are relatively mild. Hematomas and pneumothoraces are among those. The most serious complication that may occur and had been reported is the development of pneumothorax during FNA of lung lesions. However, less than 5% of those are serious and require insertion of chest tube.[44–47] In addition, if the procedure is done under image guidance, immediate evacuation using the same needle is now recommended and had been successfully achieved.[45] Paying attention to the risk factors for the development of pneumothorax may decrease their rate. Hematomas are observed more frequently in patients who have coagulopathies.[48–51] Prevention of such complications is easily achieved by applying gentle pressure for longer periods after the procedure. It is also recommended to consult with the hematologist in the institution to prepare those patients who suffer from bleeding disorders or are on anticoagulation therapy. Pain and patient discomfort are relatively mild and can be prevented by appropriate preparation of patients and by applying local anesthesia, if necessary. Infections are extremely rare and can be avoided by following the international safety guidelines and sterile techniques.[52–54]

Simple

It is well known that getting most cytological samples is simple. With increasing familiarity of different sampling techniques, currently almost all institutions and health care providers are aware of the technology and it is part of routine investigative and diagnostic patient work up. Description of different types of samples will follow.

Quick

The procedure is very quick and diagnostic answers can be provided immediately at the time of procedure, if needed, or within the next 24-48 hours.[55–61]

Cost effective

The cost effectiveness of cytological examination is well documented in the literature, a feature that is becoming very critical given the current high health care costs. Compared to surgical biopsies, the amount of savings is substantial.[62–68]

WHAT IS NEEDED TO HAVE AN EFFECTIVE CYTOPATHOLOGY SERVICE?

The most important principle is to have a simple clear communication between pathologists and clinicians with the basic understanding of teamwork. In addition, using a common clear language of communication is absolutely critical to avoid mismanagement. This includes a clear understanding of the terminology, which is used in the cytopathology final report. It is always desirable to communicate with clinicians at any time. Pathologists who are trained and familiar with cytopathology are obliged to establish bridges of communications with radiologists and clinicians. This can be achieved by one on one personal contact or through tumor board settings and clinicopathological correlation conferences. This, in many times, will have a positive impact in patient care since a diagnosis based on cytological examination will not be made in vacuum. The technical aspects of establishing a cytology and aspiration services are described below.

BRANCHES OF CYTOPATHOLOGY

Exfoliative cytology

The samples represent cells that exfoliate from superficial or deep serosal or mucosal surfaces. This includes:

Gynecological samples: Papanicolaou smears are the first samples that started the exponential revolution of the cytopathology field. Recently, almost all health care providers are moving a way from the conventional Papanicolaou smears and moving to what is called fluid-based technology that can provide more accurate interpretation and allows for molecular testing for the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) infection.[69–72]

Respiratory/exfoliative cytology, which includes bronchial washing, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, and bronchial brushing cytology. Those are commonly used to detect pulmonary infections and malignancies.

Urinary cytology: Urine cytology, bladder washing, and brushing cytology. The urinary cytology field is passing through tremendous research recently. So, in addition to cytomorphological examination, the utilization of urine samples for detection of common chromosomal aberrations in urothelial neoplasms has been recently refined. Commercial kits utilizing the Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH) are already available and in use.[73–77]

Body fluid cytology: Common samples include pleural fluid, pericardial fluid, peritoneal fluid, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology. Similar to respiratory samples, those are also used mainly to detect malignancies and infections.

Gastrointestinal Tract: Sampling the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract is becoming a routine procedure during endoscopy. Brushing samples are used to detect viral and fungal infections, and neoplasia with its precursor lesions.

Discharge cytology: Discharge from any anatomic location can be easily examined to investigate infections and malignancies. The most common sample is breast nipple discharge that is used as a screening method for detection of mammary carcinoma.[78,79]

Scrape cytology: This technique is very simple and can be performed by either clinicians or pathologists at the bedside or in the clinic. Detection of infections and cancer cells at any surface (skin or mucosa) can be quick and accurate.[80–84]

Aspiration cytology

Different names are used to describe this expanding technique. The most famous ones are FNA, fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), and needle aspiration biopsy cytology (NABC). All of them mean the same thing; aspirating cellular material using a fine needle to make a diagnosis. This technique has been used from any lesion in the body which includes two major areas:

Palpable lesions: Palpable lesions can be targeted by a clinician and preferably by an experienced cytopathologist. The advantages of having a cytopathologist performing or at least be available to confirm material adequacy are well studied in the literature (see below).

Non-palpable lesions: The non-palpable lesions are usually done with the help of image analysis (CT scan-guided, ultrasound-guided, fluoroscopy-guided, and recently endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration).

The benefits of having a pathologist/cytopathologist performing or available at the time of fine needle aspiration are well documented.[62,63,85,86] They are summarized as follows:

Making sure that the material is adequate for making specific diagnosis. This needs the use of immediate stains on smears with microscopic evaluation.

The ability to triage the case at that time. This means that after the initial evaluation of the smears the pathologist/cytopathologist will decide if additional material is needed to do ancillary studies such as cultures, molecular pathology studies, cytogenetic analysis, and immunophenotypic analysis by flow cytometry.[87–89]

The pathologist will be able to see the patient, note history, and perform quick physical examination. This will allow the pathologist to have a feeling and understanding of the clinical condition of the patient and formulate a clinically based differential diagnosis.

TECHNICAL ASPECTS OF CYTOLOGY

The initial smears are usually stained by a quick stain (stains, which needs approximately one minute to perform) such as Diff Quick (DQ) stain, a modified Romanowsky stain. This type of stain is done on slides with material after air-drying and this is why they are also called air-dried based stains. The other set of slides are fixed in basic ethanol-based solution (preferable 95% ethanol) for different type of stain, the Papanicolaou stain. In addition to the previous smears which are prepared at the time of the fine needle aspiration, the rest of the material is usually flushed in a ethanol or formalin-based solution after which the material is centrifuged and a small mini biopsy is created from the concentrated cellular material at the bottom of the tube; this is known as the cell block. The slides from the cell block are usually stained by a regular Hematoxylin and Eosin (HandE) stain. These three types of stains are commonly used in different laboratories. Each one of those has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, DQ stain is good for microorganisms, cytoplasm, and background material staining. In the meantime, Papanicolaou stain is more superior for demonstrating the nuclear details, which are the most important and specific in making the diagnosis of malignancy. The HandE stain combines the advantages of both Papanicolaou and DQ stains and gives the pathologist a chance to evaluate tissue-like stains similar to routine biopsies.

Different types of smear preparations are utilized in the cytopathology laboratory, which includes:

Direct smears as described above.

Cytocentrifuge smears, which are prepared using the cytocentrifuge method. This method concentrates the material and is especially advantageous when few cells are present in a large amount of fluid, such as pleural or peritoneal fluids.

Centrifuge smears using membrane filters. This method utilizes the use of paper filter with very small pores to trap contaminating material. It is becoming obsolete since the slide cellular morphology is usually compromised.

Monolayer liquid-based cytology. This technology is now the standard method that is used to prepare Papanicolaou smears. The smears are superior to their conventional counterparts and also allow testing for Human Papilloma Virus DNA particles.[69–72] The cells are laid on the slide in a monolayer fashion and the background is clean

The last groups of slides are those prepared using the Cellblock technique, as described above. Those slides are prepared utilizing formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. The availability of such material provides the pathologist with material that can be used to do special necessary stains. Microorganisms and immunohistochemical stains are the most commonly used.[90,91]

FINE NEEDLE ASPIRATION TECHNIQUE

There is still no agreed upon standard for the best aspiration technique in cytopathology. However, all FNA experts agree on one thing, every aspirator have to get comfortable with one method and modify it as more experience is gained. The bottom line is to get enough diagnostic cells from the area of interest. The gauges of the needles used vary, however, 21-25 French gauge needles are the most frequent. Whether to use a gun (syringe holder) or not when negative pressure is utilized, is left for the level of comfort of the aspirator. Some believe that using the gun provides more control and more cells. The most common techniques [Figures 5 and 6] that are used include:

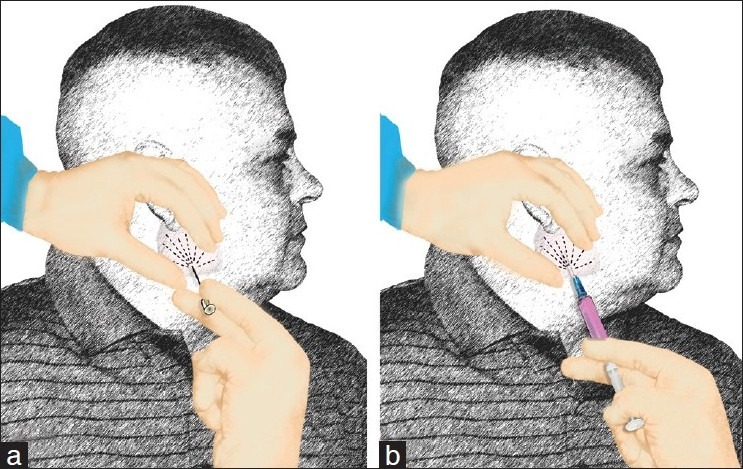

Figure 5.

Diagram demonstrating the techniques we use to perform FNA. (a) we prefer to start with aspiration using a needle without syringe or suction (also known as the French technique or Zajdela technique). The advantage of this technique is providing a nice thin smear with less crush artifacts enabling the interpreter of optimum cytological morphology to proceed with appropriate triage. (b) the following passes can be used using a syringe with suction using negative pressure to increase cellularity. The aspiration can be done with or without commercially available “guns” depending on the aspirator preference (reprinted with permission from Al-Abbadi, Editor, Salivary Gland Cytology: A Color Atlas, Wiley-Blackwell 2011).

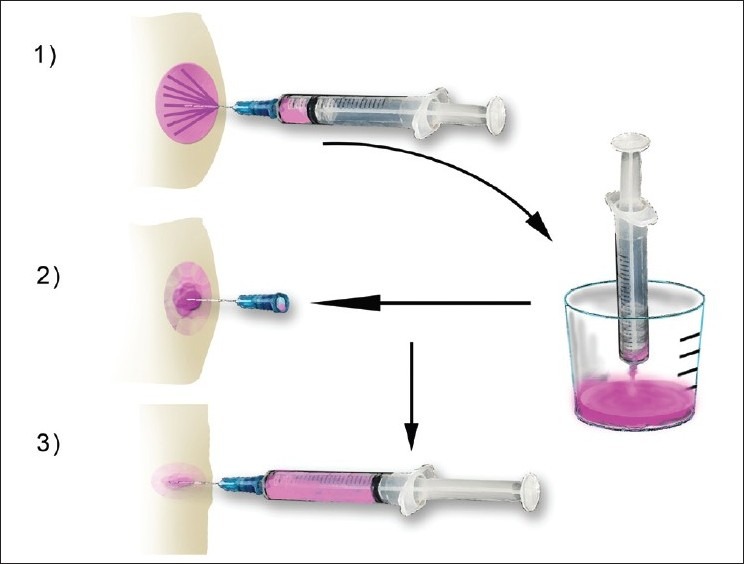

Figure 6.

Diagram showing the steps that are used when aspirating a cystic mass. Re-aspiration of cystic lesions while keeping the needle of the first pass inside the mass is a very helpful trick that helps sample the wall of the lesion and believed to increase sensitivity (reprinted with permission from Al-Abbadi, Editor, Salivary Gland Cytology: A Color Atlas, Wiley-Blackwell 2011).

Aspiration using a fine needle (gauge range 21-25) without negative pressure or a syringe. This technique is also known as “the French technique” and clinicians, radiologists and pathologists who use this method believe that it is less traumatic than the others and yield enough diagnostic cells by the mere capillary pressure.

Aspiration using a syringe and needle without negative pressure. This method allows the aforementioned capillary pressure to push cells in the hub of the needle avoiding the trauma of negative pressure. It is believed that adding the syringe will allow collection of fluids if the lesion turned to be cystic.

Aspiration using a syringe and needle with utilization of negative pressure. The amount of negative pressure varies; however, 2-3 cm. of negative pressure in a 10 ml syringe is commonly used. This is the method that the author uses without a gun and inserting the needle in a circular way to sample the whole area of the lesion.

WHAT ARE THE ANCILLARY STUDIES WHICH COULD BE USED ON CYTOLOGICAL MATERIAL?

Basically all ancillary studies can be done using cellular material obtained either from exfoliative or FNA technique. These include:

Simple special stains such as stains for microorganisms.

Immunohistochemistry [Figure 4].

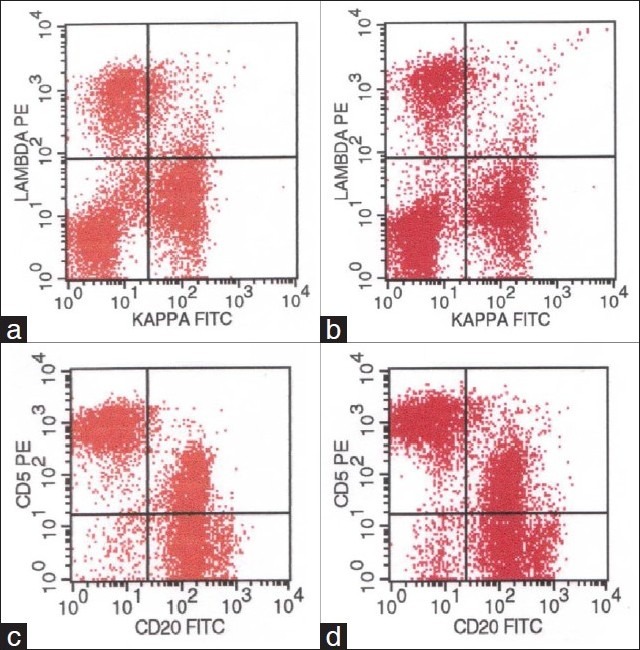

low cytometry [Figure 3].

Cytogenetic analysis.

Molecular pathology studies.

Electron microscopy

Figure 3.

Flow cytometry dot blot images from a submental lymph node. The panels on the left side are from the FNA material using the CRAT method and the panels on the right are from the same patient after the node was excised surgically. Both panels are identical demonstrating the efficiency of the “CRAT” method.

THE CYTOPATHOLOGY REPORT

To have an informative final cytopathology report after doing the procedure and making the appropriate studies to make a specific diagnosis, it is very important that it expresses few important components.

Adequacy

It is recommended that a statement describing if the material was adequate to make an interpretation is inserted in the final report. This becomes critical if the material is inadequate and the final message is to re-evaluate and/or re-investigate. As mentioned before, the presence of a pathologist or performance of the procedure by a pathologist is highly recommended in order to increase the adequacy rate.

Diagnosis

A specific diagnosis is always desired when possible. Sometimes the diagnosis is broad, such as “positive for malignant cells” and then this will be followed by descriptive diagnosis and a comment entailing a differential diagnosis to help the clinicians. In some cases, not all the diagnostic criteria are present or the atypical cells are very few; in these circumstances a “suspicious for malignancy” diagnostic category can be used. This has to be interpreted so that a second diagnostic approach is necessary.

Descriptive diagnosis (microscopic description)

Sometimes descriptive diagnosis and microscopic description of the smears may be helpful for the clinicians to make a therapeutic decision. For example, if a nipple discharge was submitted on two smears from the clinician's office and sent to pathology department and those smears contained numerous macrophages but no mammary epithelial cells are seen for evaluation. Although no epithelial cells are present in this case, the features are most likely consistent with a benign process since the increased number of macrophages and the lack of epithelial cells. In this circumstance, writing a simple microscopic descriptive diagnosis is of a great help to the clinician.

Comment

In certain circumstances a comment is needed to clarify or add some information that may harbor clinical importance.

Recommendations

Sometimes we need to call the clinicians and discuss the case with him either face to face or over the telephone.

FACTORS THAT AFFECT ADEQUACY

The presence of a pathologist/cytopathologist at the time obtaining material, especially in fine needle aspiration biopsy procedures, is highly recommended and saves a lot of effort and money in making one procedure diagnostic and cost effective. However, sometimes the material is non-diagnostic or acellular, and this should be conveyed in the final cytopathology report. So careful reading of the final cytopathology report is mandatory so that no misunderstanding or miscommunication can occur. Sometimes the material is sub optimal due to multiple factors, the most frequent are:

Air drying artifacts (leaving the smears for too long before staining). This will sometimes give false impressions of enlargement of the cells and nuclei, which in inexperienced hands may increase the incidence of false positive diagnosis.

Marked acute and chronic inflammation. The presence of marked inflammation sometime obscure diagnostic cellular details. Paying attention to this is very important. Taking into consideration the history and the clinical scenario of the patient should alert the cytopathologist from making a false/negative diagnosis. A comment in the report indicating that there is marked inflammation obscuring cellular details may be a necessity and this process should always be conveyed to the clinician to make sure that appropriate patient triage is carried out.

Sometime the material contains too many blood elements, especially red blood cells. These cells which are usually characteristic of certain organs (such as thyroid and liver) have to be interpreted with caution and thorough screening of the slides is mandatory so that abnormal/malignant cells can be detected and interpreted appropriately.

CYTOLOGICAL FEATURES OF MALIGNANCY

There is no single feature that is diagnostic of malignancy. It is the constellation of multiple factors that vary depending on the tissue aspirated, the collection technique and the smear preparation method. It is very important to be aware of these variables before attempting to make a final cytological diagnosis. The general features of malignancy in cytological slides are high cellularity, cellular enlargement, increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear hyperchromasia, discohesiveness of cells, prominent and large nucleoli, abnormal distribution of nuclear chromatin, increased mitotic activity and specially the presence of abnormal ones, nuclear membrane abnormalities, cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, and background tumor necrosis (also known as tumor diathesis). Ultimately, we are all responsible for providing an accurate cytological diagnosis.

Problems can arise anytime anywhere from the time the patient is seen until the time the final report is transcribed and faxed or sent to the clinician. Trouble shooting is very important to identify problems, which can arise anytime.

DIAGNOSTIC PITFALLS

Diagnostic pitfalls can still occur and are usually due to:[92–94]

Poor collection technique: This can occur when the appropriate slides or containers with appropriate fixatives are not used at the time of the procedure. This can be resolved by consulting with the pathology/cytopathology department for help.

Poor fixation: This is sometimes seen when there is no experience with cytopathology material preparation and collection. Communication with your pathologist is recommended.

Inflammatory changes: As described before, sometime extensive inflammation may obscure cellular details and prevent appropriate interpretation. To avoid this problem, treating the patient and repeating the procedure afterwards is recommended.

Cellular changes related to radiation and/or chemotherapy: This issue comes up if the patient had already been diagnosed with malignancy and was treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. Certain changes are induced by these treatment modalities. To decrease the pitfalls from these changes, appropriate and detailed history should be given by clinicians and awareness of the changes by the pathologist should be taken into consideration.

Atypical cellular changes related to hemorrhage, infarction, or necrosis can be problematic. Awareness of these changes by the cytopathologist is very helpful to prevent both false positive and false negative diagnosis. Having a pathologist/cytopathologist at the time of the procedure or performance of the procedure by a pathologist will help alert the pathologist to these changes.

FALSE NEGATIVE AND FALSE POSITIVE DIAGNOSIS

Despite efforts to be as accurate as possible, both false negative[95–99] and positive[100–103] diagnosis can still occur. False negative diagnoses are most commonly related to:

Desmoplasia: This is defined as the presence of fibrosis which is induced by certain tumors due to secretion of fibrogenic materials. Many tumors can cause fibrosis around the malignant cells. The most notorious are mammary, pancreatic and billiary tree carcinomas in addition to nodular sclerosing Hodgkin's lymphoma. Applying negative pressure and multiple passes during the FNA procedure can help.

Well-differentiated tumor cells: Certain tumors are extremely well-differentiated and they resemble their original cells. For example, well differentiated thyroid follicular carcinoma and well differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma can be deceiving. Awareness of these tumors and appropriate understanding of limitations of cytology is recommended. In these circumstances, making the final diagnosis on tissue sections probably is more appropriate.

Sampling problems: Sometimes the needle is not in the appropriate lesion of interest. This can be resolved by having an experienced aspirator and judicious utilizing of image guidance.

The presence of inflammation, radiation, and chemotherapy changes sometime can be over interpreted. Applying strict cytological criteria in these situations is very helpful.

On the other hand, false positive diagnosis is usually caused by:

Pregnancy: Pregnancy sometimes can increase cell size in Papanicolaou smears. Awareness by the pathologist and providing appropriate history is recommended.

Contamination: Contamination can occur either through the needle tract or during processing. Awareness of this potential problem and being diligent regarding following the safety protocols between cases is very important and will decrease the impact of this issue.

Inflammation and inflammatory changes, radiation and chemotherapy effects sometimes will lead to false positive diagnosis. Awareness and applying strict criteria after receiving accurate history is the key to avoid this diagnostic trap.

The presence of hemorrhage and infarction sometimes induce atypical changes in the cells. Awareness of this issue, which includes the presence of necrotic material and blood elements, should alert the pathologist to avoid false positive diagnosis.

Inexperience by the pathologist may induce false positive diagnosis. To eliminate this issue, consultation with other colleagues in the department of pathology is always helpful. As part of routine quality control and quality assurance in the cytopathology laboratories, it is highly recommended to have two pathologists co-sign any new diagnosis of malignancy.[104,105]

DIFFICULT AND TOUGH DIAGNOSIS

Each organ has its own diagnostic limitation by cytology. However, common examples are provided in this list:

Well-differentiated tumors (in particular liver and thyroid adenocarcinomas.

A reactive mesothelial cell versus well differentiated mesothelioma is sometimes difficult. Correlation with the clinical and radiological picture is always helpful.

Reactive conditions in the CSF have to be interpreted with extreme caution.

Glandular lesions on Pap smears. Those are sometimes difficult, and communication with a gynecologist in the same situation to establish a common language and triaging protocols are very helpful.

Breast: Ductal carcinoma in situ versus invasive ductal carcinoma is difficult to do on cytology. In addition, lobular lesions are sometime easily missed on cytology material. Awareness of these lesions and common language communication with the clinician is very helpful.

Respiratory lesions: Small cell carcinomas cells in sputum cytology sometimes are missed due to their small size and marked degeneration. Well-differentiated carcinomas in general are not easy to diagnosis. Awareness and correlation of the clinical, radiological, and bronchoscope picture is very helpful.

Urinary cytology: Low grade transitional cell lesions are difficult to diagnose by urine cytology. Communication with the urologist and correlation with the cystoscopic picture is of optimum importance.

Lymph nodes: The diagnosis of low-grade lymphoproliferative disorders is difficult based on cytology alone. To eliminate this issue, using the ancillary studies with immunophenotypic analysis either by immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry is very critical.

Soft tissue: Low grade neoplasms are sometime difficult. Awareness of the clinical and radiological picture with appropriate sampling and excellent communication with the clinicians is very helpful.

Prostate: There is a consensus agreement that FNA of the prostate is not recommended since differentiation between prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive carcinoma is practically impossible based on cytomorphology alone.[106–108]

Pancreas: FNA of pancreatic lesions, especially if there is pancreatitis, may give rise to false positive diagnosis. Awareness of the patient's history and the presence of calcification on radiological images are very helpful clues. In addition, cystic neoplasms are difficult to further be specified based on cytological examination alone.

Central nervous system: As it is difficult on surgical biopsies, separating low grade gliomas from gliosis is also difficult on cytomorphology. When screening CSF samples or contents aspirated from brain reservoirs, awareness about tumors that shed cells is very helpful.

CONCLUSIONS

Utilizing the science of cytopathology whether exfoliative or FNA is cost effective, fast, simple and accurate. With the recent improvements in technical aspects and the appearance of cell block technique in cytopathology, the old gold standard of “must have tissue to make an accurate diagnosis” is rapidly changing.

Team work emphasizing excellent communication skills is very important between pathologists and clinicians.

All the information about the patient should be given to the pathologist in order to decrease the frequency of pitfalls that were described.

Encouragement of clinical pathologic correlation conferences and tumor boards is very helpful to establish common language and protocols with appropriate guidelines for diagnostic utilization of cytology materials.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frable WJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy: A review. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:9–28. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(83)80042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frable WJ. Integration of surgical and cytopathology: A historical perspective. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;13:375–8. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840130504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demay RM. The Art and Science of Cytopathology. 1st ed 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cibas ES, Ducatman BS. Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 2nd ed 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geisinger KR, Stanley MW, Raab SS, Silverman JF, Abati A. Modern Cytopathology. 1st ed 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin HE, Ellis EB. Biopsy by needle puncture and aspiration. Ann Surg. 1930;92:169–81. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193008000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart FW. The diagnosis of tumors by aspiration biopsy. Am J Pathol. 1933;9:801–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ameican Board of Pathology. 2005. Available from: http://www.abpath.org .

- 9.American Council of Graduate Medical Education. 2005. Available from: http://www.acgme.org . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Rangdaeng S, Ya-In C, Settakorn J, Chaiwun B, Bhothirat C, Sirivanichai C, et al. Cytological diagnosis of lung cancer in Chiang Mai, Thailand: Cyto-histological correlation and comparison of sensitivity of various methods. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85:953–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez LV, Mishra G, Forsmark C, Draganov PV, Petersen JM, Hochwald SN, et al. Role of endoscopic ultrasound and EUS-guided fine needle aspiration in the diagnosis and treatment of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2002;25:222–8. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Sriram PV, Topalidis T, Jaeckle S, Thonke F, et al. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytodiagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:534–40. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.109589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas JO, Adeyi D, Amanguno H. Fine-needle aspiration in the management of peripheral lymphadenopathy in a developing country. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21:159–62. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199909)21:3<159::aid-dc2>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison AC, Jayasundera T. Mycobacterial cervical adenitis in Auckland: Diagnosis by fine needle aspirate. N Z Med J. 1999;112:7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dajani YF, Kilani Z. Role of testicular fine needle aspiration in the diagnosis of azoospermia. Int J Androl. 1998;21:295–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1998.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merchant WJ, Thomas SM, Coppen MJ, Prentice MG. The role of thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology in a District General Hospital setting. Cytopathology. 1995;6:409–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.1995.tb00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T, Nagira K, Marui T, Akisue T, Hitora T, Nakatani T, et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the initial diagnosis of bone lesions. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:793–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edoute Y, Malberger E, Tibon-Fishe O, Assy N. Non-imaging-guided fine-needle aspiration of liver lesions: A retrospective study of 279 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:98–102. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amedee RG, Dhurandhar NR. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1551–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorda M, Rey L, Hanly A, Ganjei-Azar P. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of bone: Accuracy and pitfalls of cytodiagnosis. Cancer. 2000;90:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gharib H. Changing concepts in the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1997;26:777–800. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gharib H. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules: Advantages, limitations, and effect. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:44–9. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Texter JH, Jr, Neal CE. Current applications of immunoscintigraphy in prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:549–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta AK, Nayar M, Chandra M. Reliability and limitations of fine needle aspiration cytology of lymphadenopathies. An analysis of 1,261 cases. Acta Cytol. 1991;35:777–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Celle G, Savarino V, Biggi E, Mansi C, Ceppa P, Cicio GR, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytodiagnosis: A simple and safe procedure for cancer of the pancreas. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1986;10:545–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider KL, Schreiber K, Silver CE. The initial evaluation of masses of the neck by needle aspiration biopsy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984;159:450–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caddy G, Conron M, Wright G, Desmond P, Hart D, Chen RY. The accuracy of EUS-FNA in assessing mediastinal lymphadenopathy and staging patients with NSCLC. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:410–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00092104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kontzoglou K, Moulakakis KG, Konofaos P, Kyriazi M, Kyroudes A, Karakitsos P. The role of liquid-based cytology in the investigation of breast lesions using fine-needle aspiration: A cytohistopathological evaluation. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:75–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Centeno BA, Szydlo T, Regan S, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: A report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dodd LG, Scully SP, Cothran RL, Harrelson JM. Utility of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of primary osteosarcoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:350–3. doi: 10.1002/dc.10196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oertel YC. Fine-needle aspiration in the evaluation of thyroid neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 1997;8:215–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02738788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Javadzadeh B, Finley J, Williams HJ. Fine needle aspiration cytology of mammary duct ectasia: Report of a case with novel cytologic and immunocytochemical findings. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:1027–31. doi: 10.1159/000328349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sturgis CD, Silverman JF, Kennerdell JS, Raab SS. Fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis of primary epithelial tumors of the lacrimal gland and ocular adnexa. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;24:86–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0339(200102)24:2<86::aid-dc1016>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chhieng D, Cohen JM, Waisman J, Fernandez G, Cangiarella J. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of hemangiopericytoma: A report of five cases. Cancer. 1999;87:190–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990825)87:4<190::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taneri F, Poyraz A, Tekin E, Ersoy E, Dursun A. Accuracy and significance of fine-needle aspiration cytology and frozen section in thyroid surgery. Endocr Regul. 1998;32:187–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shabb NS, Fahl M, Shabb B, Haswani P, Zaatari G. Fine-needle aspiration of the mediastinum: A clinical, radiologic, cytologic, and histologic study of 42 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;19:428–36. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199812)19:6<428::aid-dc5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renshaw AA, Granter SR, Cibas ES. Fine-needle aspiration of the adult kidney. Cancer. 1997;81:71–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith MB, Katz R, Black CT, Cangir A, Andrassy RJ. A rational approach to the use of fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the evaluation of primary and recurrent neoplasms in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1245–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doorbar J, Cubie H. Molecular basis for advances in cervical screening. Mol Diagn. 2005;9:129–42. doi: 10.1007/BF03260081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turkistanli EC, Sogukpinar N, Saydam BK, Aydemir G. Cervical cancer prevention and early detection--the role of nurses and midwives. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2003;4:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor LA, Sorensen SV, Ray NF, Halpern MT, Harper DM. Cost-effectiveness of the conventional papanicolaou test with a new adjunct to cytological screening for squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix and its precursors. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:713–21. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chi DS, Gemignani ML, Curtin JP, Hoskins WJ. Long-term experience in the surgical management of cancer of the uterine cervix. Semin Surg Oncol. 1999;17:161–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199910/11)17:3<161::aid-ssu4>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stanley K, Stjernsward J, Koroltchouk V. Women and cancer. World Health Stat Q. 1987;40:267–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mullan CP, Kelly BE, Ellis PK, Hughes S, Anderson N, McCluggage WG. CT-guided fine-needle aspiration of lung nodules: Effect on outcome of using coaxial technique and immediate cytological evaluation. Ulster Med J. 2004;73:32–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shantaveerappa HN, Mathai MG, Byrd RP, Jr, Karnad AB, Mehta JB, Roy TM. Intervention in patients with pneumothorax immediately following CT-guided fine needle aspiration of pulmonary nodules. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:CR401–4. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byrd RP, Jr, Fields-Ossorio C, Roy TM. Delayed chest radiographs and the diagnosis of pneumothorax following CT-guided fine needle aspiration of pulmonary lesions. Respir Med. 1999;93:379–81. doi: 10.1053/rmed.1999.0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia Rio F, Diaz Lobato S, Pino JM, Atienza M, Viguer JM, Villasante C, et al. Value of CT-guided fine needle aspiration in solitary pulmonary nodules with negative fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Acta Radiol. 1994;35:478–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rios A, Rodriguez JM, Martinez E, Parrilla P. Cavernous hemangioma of the thyroid. Thyroid. 2001;11:279–80. doi: 10.1089/105072501750159732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bousamra M, 2nd, Clowry L., Jr Thoracoscopic fine-needle aspiration of solitary pulmonary nodules. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1191–3. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell SC, Novick AC, Herts B, Fischler DF, Meyer J, Levin HS, et al. Prospective evaluation of fine needle aspiration of small, solid renal masses: Accuracy and morbidity. Urology. 1997;50:25–9. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bardales RH, Stanley MW. Subcutaneous masses of the scalp and forehead: Diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;12:131–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840120208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee LS, Saltzman JR, Bounds BC, Poneros JM, Brugge WR, Thompson CC. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic cysts: A retrospective analysis of complications and their predictors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:231–6. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ryan AG, Zamvar V, Roberts SA. Iatrogenic candidal infection of a mediastinal foregut cyst following endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2002;34:838–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grandval P, Picon M, Coste P, Giovannini M, Thomas P, Lafon J. Infection of submucosal tumor after endosonography-guided needle biopsy. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:566–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kramer H, Groen HJ. Current concepts in the mediastinal lymph node staging of nonsmall cell lung cancer. Ann Surg. 2003;238:180–8. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000081086.37779.1a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mazza E, Maddau C, Ricciardi A, Falchini M, Matucci M, Ciarpallini T. On-site evaluation of percutaneous CT-guided fine needle aspiration of pulmonary lesions. A study of 321 cases. Radiol Med (Torino) 2005;110:141–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nayak S, Puranik SC, Deshmukh SD, Mani R, Bhore AV, Bollinger RC. Fine-needle aspiration cytology in tuberculous lymphadenitis of patients with and without HIV infection. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:204–6. doi: 10.1002/dc.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krane JF, Renshaw AA. Relative value and cost-effectiveness of culture and special stains in fine needle aspirates of the lung. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:305–11. doi: 10.1159/000331608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martinez-Parra D, Nevado-Santos M, Melendez-Guerrero B, Garcia-Solano J, Hierro-Guilmain CC, Perez-Guillermo M. Utility of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of granulomatous lesions of the breast. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;17:108–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199708)17:2<108::aid-dc5>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lapuerta P, Martin SE, Ellison E. Fine-needle aspiration of peripheral lymph nodes in patients with tuberculosis and HIV. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;107:317–20. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/107.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lau SK, Wei WI, Hsu C, Engzell UC. Efficacy of fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of tuberculous cervical lymphadenopathy. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104:24–7. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100111697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eedes CR, Wang HH. Cost-effectiveness of immediate specimen adequacy assessment of thyroid fine-needle aspirations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:64–9. doi: 10.1309/XLND-TE28-9WAQ-YK0Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nasuti JF, Gupta PK, Baloch ZW. Diagnostic value and cost-effectiveness of on-site evaluation of fine-needle aspiration specimens: Review of 5,688 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:1–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chaiwun B, Settakorn J, Ya-In C, Wisedmongkol W, Rangdaeng S, Thorner P. Effectiveness of fine-needle aspiration cytology of breast: Analysis of 2,375 cases from northern Thailand. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:201–5. doi: 10.1002/dc.10067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aabakken L, Silvestri GA, Hawes R, Reed CE, Marsi V, Hoffman B. Cost-efficacy of endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration vs.mediastinotomy in patients with lung cancer and suspected mediastinal adenopathy. Endoscopy. 1999;31:707–11. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vetto J, Schmidt W, Pommier R, Ditomasso J, Eppich H, Wood W, et al. Accurate and cost-effective evaluation of breast masses in males. Am J Surg. 1998;175:383–7. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mui S, Li T, Rasgon BM, Hilsinger RL, Rumore G, Puligandla B, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of multihole fine-needle aspiration of head and neck masses. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:759–64. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199706000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown LA, Coghill SB. Cost effectiveness of a fine needle aspiration clinic. Cytopathology. 1992;3:275–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.1992.tb00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schiller CL, Nickolov AG, Kaul KL, Hahn EA, Hy JM, Escobar MT, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus detection: A split-sample comparison of hybrid capture and chromogenic in situ hybridization. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:537–45. doi: 10.1309/13NM-AK8J-3N1Y-JXU1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matthews-Greer J, Rivette D, Reyes R, Vanderloos CF, Turbat-Herrera EA. Human papillomavirus detection: Verification with cervical cytology. Clin Lab Sci. 2004;17:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yarkin F, Chauvin S, Konomi N, Wang W, Mo R, Bauchman G, et al. Detection of HPV DNA in cervical specimens collected in cytologic solution by ligation-dependent PCR. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:450–6. doi: 10.1159/000326549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Quddus MR, Zhang S, Sung CJ, Liu F, Neves T, Struminsky J, et al. Utility of HPV DNA detection in thin-layer, liquid-based tests with atypical squamous metaplasia. Acta Cytol. 2002;46:808–12. doi: 10.1159/000327051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Degtyar P, Neulander E, Zirkin H, Yusim I, Douvdevani A, Mermershtain W, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization performed on exfoliated urothelial cells in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Urology. 2004;63:398–401. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sarosdy MF, Schellhammer P, Bokinsky G, Kahn P, Chao R, Yore L, et al. Clinical evaluation of a multi-target fluorescent in situ hybridization assay for detection of bladder cancer. J Urol. 2002;168:1950–4. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64270-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sokolova IA, Halling KC, Jenkins RB, Burkhardt HM, Meyer RG, Seelig SA, et al. The development of a multitarget, multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization assay for the detection of urothelial carcinoma in urine. J Mol Diagn. 2000;2:116–23. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60625-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Halling KC, King W, Sokolova IA, Meyer RG, Burkhardt HM, Halling AC, et al. A comparison of cytology and fluorescence in situ hybridization for the detection of urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2000;164:1768–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Inoue T, Nasu Y, Tsushima T, Miyaji Y, Murakami T, Kumon H. Chromosomal numerical aberrations of exfoliated cells in the urine detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization: Clinical implication for the detection of bladder cancer. Urol Res. 2000;28:57–61. doi: 10.1007/s002400050011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamamoto D, Shoji T, Kawanishi H, Nakagawa H, Haijima H, Gondo H, et al. A utility of ductography and fiberoptic ductoscopy for patients with nipple discharge. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;70:103–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1012990809466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fujii M, Ishii Y, Nagao M, Wakabayashi T, Fukahori S, Goto A, et al. A cytologic diagnosis of breast secretions--application of cytology to the mass survey of breast cancer. Gan No Rinsho. 1988;34:174–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khunamornpong S, Siriaunkgul S. Scrape cytology of the ovaries: Potential role in intraoperative consultation of ovarian lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:250–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.10273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tohnosu N, Nabeya Y, Matsuda M, Akutsu N, Watanabe Y, Sato H, et al. Rapid intraoperative scrape cytology assessment of surgical margins in breast conservation surgery. Breast Cancer. 1998;5:165–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02966689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Linehan JJ, Melcher DH, Strachan CJ. Rapid outpatient detection of rectal cancer by gloved digital scrape cytology. Acta Cytol. 1983;27:146–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kobayashi TK, Kaneko C, Sugishima S, Kusukawa J, Kameyama T. Scrape cytology of oral pemphigus. Report of a case with immunocytochemistry and light, scanning electron and transmission electron microscopy. Acta Cytol. 1999;43:289–94. doi: 10.1159/000330996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Garcia Canton JA, Navarrete Ortega M, Rafael Ribas E. Herpes simplex and herpes varicella-zoster. Cytological and ultrastructural study. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1980;8:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Layfield LJ, Bentz JS, Gopez EV. Immediate on-site interpretation of fine-needle aspiration smears: A cost and compensation analysis. Cancer. 2001;93:319–22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Silverman JF, Lannin DR, O’Brien K, Norris HT. The triage role of fine needle aspiration biopsy of palpable breast masses. Diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:731–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sigstad E, Dong HP, Davidson B, Berner A, Tierens A, Risberg B. The role of flow cytometric immunophenotyping in improving the diagnostic accuracy in referred fine-needle aspiration specimens. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:159–63. doi: 10.1002/dc.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Henrique RM, Sousa ME, Godinho MI, Costa I, Barbosa IL, Lopes CA. Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry of fine needle aspirates in the diagnosis of lymphoproliferative disorders: A retrospective study. J Clin Lab Anal. 1999;13:224–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1999)13:5<224::AID-JCLA6>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Caraway NP. Strategies to diagnose lymphoproliferative disorders by fine-needle aspiration by using ancillary studies. Cancer. 2005;105:432–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rader AE, Avery A, Wait CL, McGreevey LS, Faigel D, Heinrich MC. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors using morphology, immunocytochemistry, and mutational analysis of c-kit. Cancer. 2001;93:269–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Han J, Kim MK, Nam SJ, Yang JH. E-cadherin and cytokeratin subtype profiling in effusion cytology. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:826–33. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.6.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Katz RL. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of fine-needle aspiration of lymph nodes. Monogr Pathol. 1997:118–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Goellner JR. Problems and pitfalls in thyroid cytology. Monogr Pathol. 1997:75–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Koss LG. Errors and pitfalls in cytology of the lower urinary tract. Monogr Pathol. 1997:60–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ustun M, Risberg B, Davidson B, Berner A. Cystic change in metastatic lymph nodes: A common diagnostic pitfall in fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:387–92. doi: 10.1002/dc.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Young NA, Mody DR, Davey DD. Misinterpretation of normal cellular elements in fine-needle aspiration biopsy specimens: Observations from the College of American Pathologists Interlaboratory Comparison Program in Non-Gynecologic Cytopathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:670–5. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0670-MONCEI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bakhos R, Selvaggi SM, DeJong S, Gordon DL, Pitale SU, Herrmann M, et al. Fine-needle aspiration of the thyroid: Rate and causes of cytohistopathologic discordance. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;23:233–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0339(200010)23:4<233::aid-dc3>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Layfield LJ, Dodd LG. Cytologically low grade malignancies: An important interpretative pitfall responsible for false negative diagnoses in fine-needle aspiration of the breast. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;15:250–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(199609)15:3<250::AID-DC15>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bhatia A. Fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of mass lesions of the salivary gland. Indian J Cancer. 1993;30:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ritter JH, Wick MR, Reyes A, Coffin CM, Dehner LP. False-positive interpretations of carcinoma in exfoliative respiratory cytology. Report of two cases and a review of underlying disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;104:133–40. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/104.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wong MP, Yuen ST, Collins RJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of pilomatrixoma: Still a diagnostic trap for the unwary. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10:365–9. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Greenberg ML, Middleton PD, Bilous AM. Infarcted intraduct papilloma diagnosed by fine-needle biopsy: A cytologic, clinical, and mammographic pitfall. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;11:188–91. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840110216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pinedo F, Vargas J, de Agustin P, Garzon A, Perez-Barrios A, Ballestin C. Epithelial atypia in gynecomastia induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. A possible pitfall in fine needle aspiration biopsy. Acta Cytol. 1991;35:229–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stelow EB, Bardales RH, Stanley MW. Pitfalls in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and how to avoid them. Adv Anat Pathol. 2005;12:62–73. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000155053.68496.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tan KB, Chang SA, Soh VC, Thamboo TP, Nilsson B, Chan NH. Quality indices in a cervicovaginal cytology service: Before and after laboratory accreditation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:303–7. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-303-QIIACC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Palmer LS, Laor E, Skinner WK, Tolia BM, Reid RE, Freed SZ. Prostate cancer screening using fine-needle aspiration cytology prior to open prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 1995;27:96–8. doi: 10.1159/000475136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schmidt JD. Clinical diagnosis of prostate cancer. Cancer. 1992;70:221–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1+<221::aid-cncr2820701308>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Juusela H, Ruutu M, Permi J, Jauhiainen K, Talja M. Can fine needle aspiration biopsy detect incidental prostatic carcinoma (T1) prior to TUR? Eur Urol. 1992;21:131–3. doi: 10.1159/000474818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]