Abstract

Iatrogenic pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS) is a known, yet rare, complication of atrial radiofrequency ablation. Alterations in pulmonary perfusion may mimic massive pulmonary embolism on a ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scintigraphy. This is particularly important due to the overlap in presenting clinical symptoms. The present case illustrates the functional significance of PVS and the changes in perfusion in response to angioplasty.

Keywords: Pulmonary embolism, pulmonary perfusion, pulmonary vein stenosis, Radiofrequency ablation, V/Q scan

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS) is a rare clinical condition with bimodal age distribution.[1] While congenital abnormalities represent the leading cause of PVS in childhood, various etiologies such as fibrosing mediastinitis, sarcoidois, and neoplastic processes were more commonly encountered in adults.[1] Recently, with the advent of the radiofrequency ablation (RFA) as a treatment for atrial fibrillation, iatrogenic causes have become the leading cause of PVS in adults.[1] The clinical manifestations of PVS include dyspnea, cough, and hemoptysis. We present this case due to the similarity of the imaging findings of PVS with massive pulmonary embolism which could potentially lead to misdiagnosis and mismanagement.

CASE REPORT

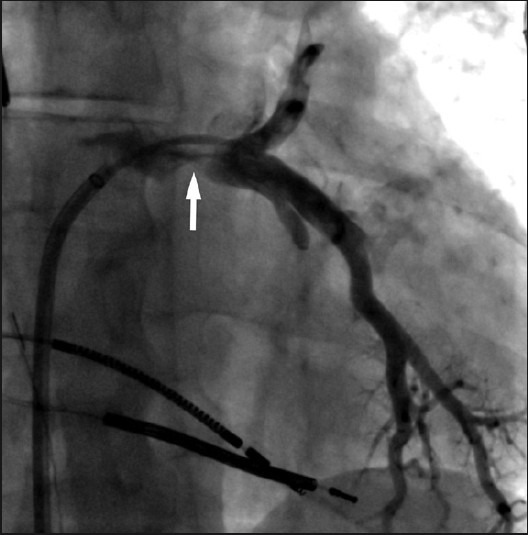

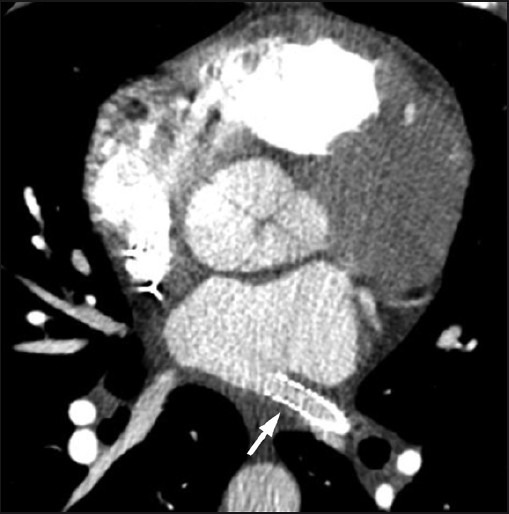

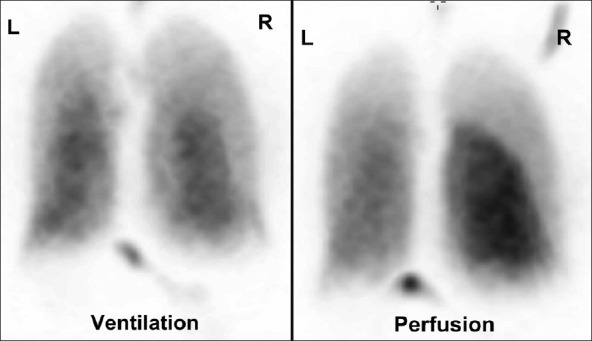

A 39-year-old male with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial, and ventricular arrhythmias underwent multiple RFA procedures for atrial fibrillation. Following the ablations, he developed progressive dyspnea and was found to have mild right superior and significant left pulmonary veins stenosis on a cardiac computed tomography (CT) [Figure 1]. A quantitative ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan demonstrated diffusely decreased perfusion to the left lung compared to the right with differential perfusion estimated at 16% and 84%, respectively [Figure 2]. There was preferential perfusion to the right lower lobe compared to the right middle and upper lobes [Figure 3]. No ventilation defects were identified. Although the pattern of mismatched perfusion defects mimics a high probability scan for pulmonary embolism, these findings were attributed to the clinically known PVS.

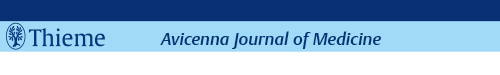

Figure 1.

Axial CT image at the level of the left atrium demonstrates a high-grade ostial stenosis involving the left superior pulmonary vein (arrow).

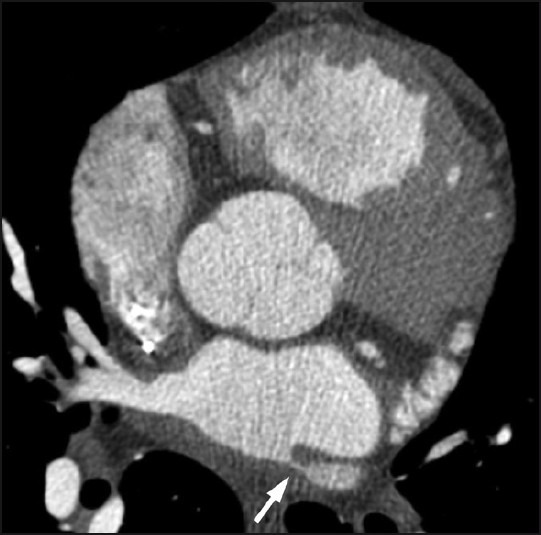

Figure 2.

Posterior projection of a ventilation/perfusion scan. The perfusion scan shows diffusely decreased uptake in the left lung and the right upper lobe. The ventilation scan shows homogenous symmetric uptake with no defects.

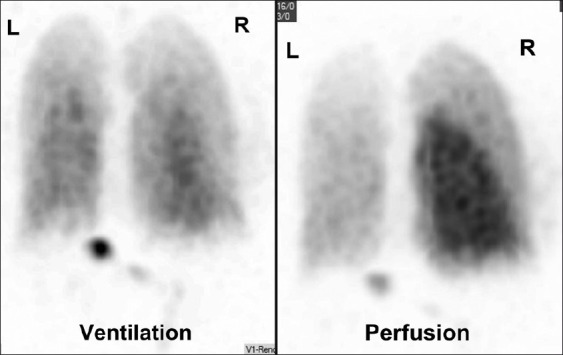

Figure 3.

Sagittal image through the right lung of a Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography of the V/Q scan shows the preferential perfusion to the right lower lobe and decreased flow to the right upper lobe due to the known right superior PVS. Radiotracer uptake is normal on the ventilation scan. This large lobar V/Q mismatch mimics a high probability V/Q scan.

Via trans-septal access, the patient underwent pulmonary vein angiography which showed high-grade stenosis at the left pulmonary venoatrial confluence [Figure 4]. Simultaneous balloon angioplasty of the left superior and inferior pulmonary venoatrial confluence was performed using 6 mm × 40 mm balloons. Subsequently, two 8 mm × 29 mm Palmaz® balloon-expandable stents (Cordis Corporation, Miami, USA) were deployed simultaneously. CT venography after 4 months revealed widely patent stents with no intrastent stenosis [Figure 5]. Quantitative V/Q scan revealed improvement in perfusion to the left lung to 36.5%. However, the preferential perfusion to the right lower lobe remained unchanged due to the untreated right upper lobe PVS [Figure 6].

Figure 4.

Pulmonary venogram via a trans-septal access. The left superior and inferior pulmonary veins are jointly draining into the left atrium with evidence of a high-grade stenosis at the ostium (arrow). This was successfully treated with placement of kissing balloon expandable stents (not shown).

Figure 5.

Axial image of a CT angiography shows a widely patent left pulmonary vein stent (arrow).

Figure 6.

Posterior planar projection of a V/Q scan post pulmonary vein stenting shows interval improvement of the left pulmonary perfusion with persistent decrease uptake in the right upper lobe due the untreated right superior pulmonary vein stenosis. The ventilation scan remains normal.

DISCUSSION

Iatrogenic PVS, as a known complication of atrial RFA, can occur days or months after the procedure.[2–5] Mild and moderate degrees of PVS which do not significantly impair pulmonary flow are usually asymptomatic. However, severe PV stenosis or occlusion can lead to severe symptoms at presentation.[3]

The clinical manifestations of PVS including dyspnea, cough, chest pain, and hemoptysis overlap with other pulmonary and cardiac diseases and may lead to occasional misdiagnosis.[1–4,6,7] Furthermore, the imaging findings can also be confused with pneumonia on chest radiographs or pulmonary embolism on a V/Q scan.[3,7] Di Biase et al., in a series of 16 patients with total PV occlusion, reported a correlation between the lung findings on CT and the severity of symptoms mimicking pulmonary embolism and lung cancer leading to unnecessary interventions such as filter placement and partial lung resection, respectively.[3]

PVS can be anatomically evaluated using echocardiography, magnetic resonance (MR), or multislice CT angiography.[3,4,6]

Although MR imaging can be reliable in depicting the stenotic lesions and the related perfusion abnormalities, it remains limited by the long acquisition times and the motion and respiration artifacts.[4] Multislice CT scan with optimized protocol for visualization of the pulmonary veins has become the study of choice in most patients owing to the fast acquisition times and the adequate spatial and temporal resolutions.[6] The functional impact of PVS can be assessed using MR perfusion or perfusion scintigraphy with high reported sensitivity and specificity.[4,5] Quantitative perfusion scintigraphy is frequently used to assess the differential pulmonary perfusion secondary to PVS and assess the response to endovascular treatment. Substantial perfusion reduction was reported when the diameter of the pulmonary vein is ≤6 mm.[4]

Angiography remains the gold standard in diagnosis of PVS. This can be performed by pulmonary artery injections or via trans-septal access which allows for optimal opacification of the veins and measurements of pressure gradients across the stenotic lesions for hemodynamic assessment of the stenosis.

Treatment has been primarily with balloon angioplasty in majority of cases with reasonably good short-term results.[1,3–5] However, restenosis is observed in approximately 50% of patients within 1 year. Stenting has been associated with a better medium-term prognosis. Nonetheless, follow-up imaging to evaluate intrastent restenosis is advocated and repeat interventions may be required to maintain patency.[1]

This case illustrates the functional significance of PVS as a complication of atrial ablation and the subsequent alterations in pulmonary perfusion which may mimic pulmonary embolism on V/Q scan. Awareness of this condition and its imaging findings is important to avoid misdiagnosis and mismanagement as previously reported.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Latson LA, Prieto LR. Congenital and acquired pulmonary vein stenosis. Circulation. 2007;115:103–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.646166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baman TS, Jongnarangsin K, Chugh A, Suwanagool A, Guiot A, Madenci A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of complications of radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:626–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Biase L, Fahmy TS, Wazni OM, Bai R, Patel D, Lakkireddy D, et al. Pulmonary vein total occlusion following catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: Clinical implications after long-term follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2493–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kluge A, Dill T, Ekinci O, Hansel J, Hamm C, Pitschner HF, et al. Decreased pulmonary perfusion in pulmonary vein stenosis after radiofrequency ablation: Assessment with dynamic magnetic resonance perfusion imaging. Chest. 2004;126:428–37. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saad EB, Rossillo A, Saad CP, Martin DO, Bhargava M, Erciyes D, et al. Pulmonary vein stenosis after radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation: Functional characterization, evolution, and influence of the ablation strategy. Circulation. 2003;108:3102–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000104569.96907.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgstahler C, Trabold T, Kuettner A, Kopp AF, Mewis C, Kuehlkamp V, et al. Visualization of pulmonary vein stenosis after radio frequency ablation using multi-slice computed tomography: Initial clinical experience in 33 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2005;102:287–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W, Zhou JP, Wu LQ, Gu G, Shi GC. Pulmonary-vein stenosis can mimic massive pulmonary embolism after radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. Respir Care. 2011;56:874–7. doi: 10.4187/respcare.00975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]