BACKGROUND

Since the Syrian conflict began over one year ago, the Government of Turkey has kept its borders open to individuals who have fled the turmoil. According to latest official figures; total of 40,807 Syrian citizens have fled into Turkey of whom 17,796 have returned back to Syria leaving 22,960 refugees in Turkish camps as of May 4, 2012.[1,2] These refugees are being hosted at nine sites including eight tented sites in Hatay and Gaziantep, and one container city in Kilis [Figure 1].[2] As of 29-30 April, the number of Syrian refugees by region is as follows: 7,148 individuals in Hatay; 6,161 individuals in Islahiye; 9,988 individuals in Kilis; and 860 individuals in Ceylanpinar.[3] Due to the rapid influx of Syrians fleeing the violence into the Turkish borders, concerns evolve about the adequate preparation and immediate humanitarian and medical needs for this emergency situation. According to information available to the Helsinki Citizens Assembly (HCA) about the camps and reports by several international visiting delegations, the camps appear to be well-equipped in terms of providing the basic needs of the displaced Syrians however the adequacy of providing necessary needs particularly health care services to the Syrians in the new camps is not well known.

Figure 1.

Sites of Syrian refugee camps in Turkey

OBJECTIVES

To assess the current situation of health at the main refugee camps and to provide a prospective strategic assessment with a view to identifying practical options, in order to facilitate the continued funding of (parallel) health services, and evaluate the need of extra Syrian physicians to assist in health care delivery at the camps.

METHODOLOGY

The scope of the evaluation covered the three main refugee campuses in Turkey for Syrian refugees. The evaluation has been carried out by a team of three consultants of the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS). The field visits were facilitated by different local officials, advisors and consultants from Ministry of Health and Ministry of Foreign affairs. A field trip which took place from April 26 to 29, 2012 and included field visits to three refugee camps (located in Altinözü, Islahyie and Kilis) with interviews of the camp committees and beneficiaries whenever feasible, data collection about current number of refugees, available services including medical personnel, and discussions with concerned Provincial and Districts Health Offices, as well as with the referral hospitals.

RESULTS

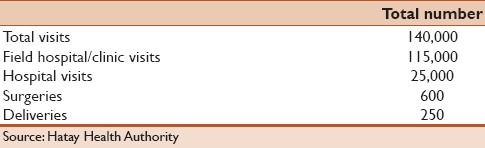

The Turkish health system is quite well developed and remarkably equitable. The ministry of health has been involved in direct health care provision inside the camps and through the referral of refugees to the Turkish hospitals. The health department directorate was visited where description of health care services and statistics were discussed with the director of health department. Table 1 reveals the total number of clinic visits, hospital admissions, surgeries and deliveries that have been conducted since the start of the conflict. Immunization was delivered to more than 95% of children aged 18 years or less.

Table 1.

Clinic and hospital visits data

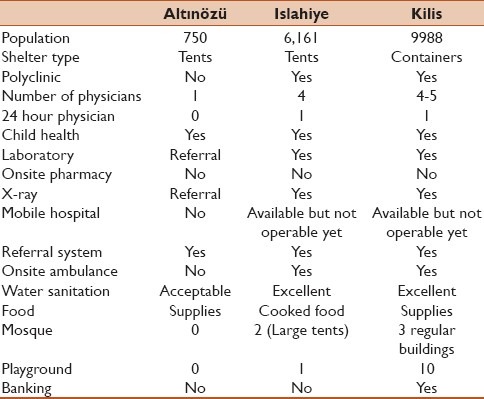

The three camps that were visited differed in shelter type, size, health and other support services. Islahyie camp [Figure 2a] that was established as a tent camp 6 weeks ago; has 6000 refugees (2000 children age 0-2 years) and has capacity of 10,000. It has a polyclinic that is staffed with four physicians (general practitioner, Ob/Gyn, pediatrician and psychiatrist), these physicians are generally present from 8 AM to 5 PM on weekdays except for the psychiatrist who is available once a week, and there is one on call physician between 5 PM and 8 AM and on weekends. There are also two ambulances and one regular car to transport cases to the local hospital. At Kilis camp [Figure 2b], health care services are delivered similarly as in Islahiye with a polyclinic that is staffed with 4-5 physicians and in addition to the onsite availability of subspecialty clinics such as ENT, plastic surgery, general surgery, urology and psychiatry). At Altinözü camp; it was reported that one general practitioner is supposed to be available daily from 8 AM to 5 PM but interruption of services have been recorded. Number of visits to the polyclinics averages around 250 visits per day with average of 50-80 visits per physician which is higher than the recommended number by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), (<50 visits/clinician), with average number of monthly visits of 3000 cases. At Islahiye there were more than 5000 medical evaluations with more than 20 births since its establishment 6 weeks ago. Cases are screened in the polyclinic at a primary level and referrals are being made to subspecialties or local hospitals based on the complexity of the cases. Onsite laboratory was present at both Islahiye and Kilis with the ability to perform most of the urgent care tests such as CBC, Chemistry 12, pregnancy test, and urinalysis in addition to quick point of care tests. Pharmacy is planned to be available at the site and currently the prescription is written and medications are dispensed in the afternoon or the next day. X-ray and Ob/Gyn ultrasound services are available along with x-ray technicians at both Islahiye and Kilis [Table 2]. Daily records are kept be in the form of a log book or tally sheets and record the patient's name, age, sex, clinical and laboratory diagnosis and treatment.

Figure 2.

Islahiye camp (a), Kilis camp (b)

Table 2.

Comparison of services provided at the three visited camps

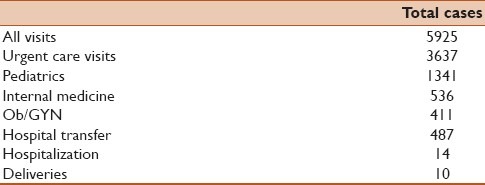

Based on the information provided from Islahiye field hospital statistics [Table 3], the average number of daily visits to the field hospital is 220 visits, with average of 78.8 visits to pediatrics, 33.1 visits to internal medicine, 28.1 to Ob/Gyn and 122.7 to urgent care. The hospital referral rate is 8.2% of the visit and the hospitalization rate is 0.24%. The utilization rate of health care services at the camp was assessed based on the provided figures for the month of April with total of 4850 consultations per month and a rate of 9.7 consultations per person per year.

Table 3.

Health care utilization statistics and Islahiye camp between March 15 and April 26, 2012

Notwithstanding the above mentioned achievements, a number of concerns must be listed, which have impacted on the effectiveness of health care delivery in the camps:

Number of cases seen by a clinician on a single day may exceed the recommended number by the NHCR at <50 visits/day/clinician especially in pediatrics.

The language barrier in addition to some unrealistic expectations, rumors, counteracts of some local individual physicians and to some extent a low level of sectarianism play a significant role in creating tension and friction between the refugees and the health care providers as wells the camp authorities. It also poses significant challenges for the treating physicians that may impact the overall quality of health care delivery.

The socioeconomic status and the low health awareness play major role in the perception of the provided health care services and difficulty in understanding a referral-based system that may lead to loss of trust to some extent with the Turkish physicians and may result in seeking heath care outside the campus or sometimes returning to Syria.

Delay in dispensing medication for more than 24 hours in some cases might be responsible for the dissatisfaction of the refugees

The abuse of the health system by the refugees with chronic problems, disabilities or congenital abnormalities that were present and unsolved for long time in their original locations put extra burden on the health care sector.

Deficiency in some of the important support services for certain cases such as rehabilitation, child psychology and some specialized services.

Lack of adequate awareness of refugees to the psychological trauma.

DISCUSSION

New arrivals are rapidly settled at the newly established tent sites, prepared by the Turkish authorities and set up by the Turkish Red Crescent. Syrian citizens living in Turkey were provided with uninterrupted services of lodging, food, health services, security, social activities, education, religious services, translation services, safety, banking and communication.[4] An emergency response plan should offer a structured approach towards improving predictability and quality of response; provide resources and capabilities to respond quickly and effectively and clarify a process for avoiding and filling gaps in the humanitarian response. The importance of coordination and collaboration among Health, Water Sanitation Hygiene (WASH) and Nutrition clusters of field staff is paramount during emergency operations.[5–9] Uddin Khan and Shahidullah (1982) documented that in one refugee camp in Bangladesh where sanitation facilities had been provided the cholera rate was 1.6 per 1,000, whereas in the two camps without facilities the rates were 4.0 and 4.3 per 1,000.[7]

There are two main components of health service delivery that affect the impact of clinical health services in conflict-affected population; the adequacy of health care services and the effectiveness of these services. Certain indicators may be used to measure these components such as outpatient consultation rate, proportion of illness episodes for which appropriate care was sought and average delay in seeking health care.[10]

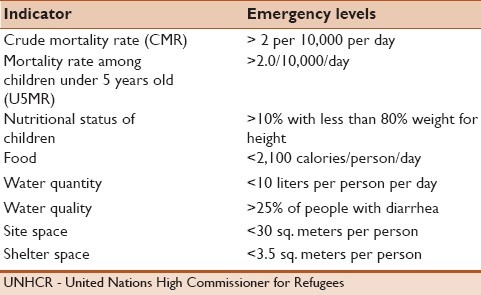

The health care services provided by the local Turkish authorities are in general adequate and appropriate, the available data and the direct observation generally indicate a satisfactory health condition in all the refugee camps over the period. There were no reported cases of measles, severe respiratory infections, severe diarrhea, malaria, or tuberculosis at the visited sites. There is a need to access detailed and specific statistics such as crude mortality rate (CMR), mortality rate among children under 5 years old, case fatality ratio among specific diseases, diagnostic accuracy rate, health worker treatment quality, delay in seeking health care or other health statistics to compare to standard reference indicators [Table 4].

Table 4.

UNHCR indicators[10]

Infection control and outbreak surveillance program needs to be enforced and certain clinical indicators are required to be monitored to assure the quality of the provided services.

The lack of adequate awareness of refugees to the psychological is one of the important observations that we found. The language barrier and cultural differences are great obstacles in addressing this important problem that may carry significant consequences such as somatization, escalation of violence and/or suicide.

It is obvious that some of the raised concerns can be solved if an organized team of Syrian physicians who speak the same language of the refugees and have a better understanding of their background and culture work very closely with Turkish physicians in collaboration with the Turkish authorities and with a clear procedure and objectives. A specialized team of psychiatrists and counselors who speak Arabic language is critically needed to accommodate the large number of cases that need special psychiatric evaluation and treatment and a training program under the supervision of experts is recommended. Special cost-effective educational programs should be delivered with the aim of intensifying actions based on priorities and coordinating needed responses. Highly complicated surgical cases that require special surgical expertise can be coordinated through a liaison office and services can be provided on case to case basis. Long term structured programs can be implemented for specific medical condition based on their prevalence and the available services. Although some regional non-governmental organizations recommended the creation of parallel health services, we did not see the need of such services based on the current level of the responses from the Turkish authorities. We recommend directing efforts to other refugee areas outside Turkey after a thorough evaluation and assessment. The situation needs to be reevaluated in case there was a remarkable increase in the number of refugees. There is a need for a dedicated medical team to coordinate and asses the emerging needs for these camps in collaboration with the Turkish authorities and health ministry.

CONCLUSION

The emergency response of the Turkish authorities has demonstrated a high level of responsibility and accountability of these clusters based on direct observation, available data and statistics. This situation logically reflects the effectiveness of health structures which have been organized to the best of the partners’ abilities with adequate funding over a protracted period, despite a number of constraints. We do not recommend funding of parallel health care services but we support building special support programs that can increase health awareness in Syrian refugees or address the language and culture differences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Government of Turkey (Briefing Kit for Turkey and News and Press Release). Uninterrupted humanitarian aid is continuing for Syrian citizens. [Last Accessed on 2012 Jun 28]. Available from: http://www.afetacil.gov.tr/Ingilizce_Site/haber_ing/haber_detay.asp?haberID=234 .

- 2.Fact Sheet, Office of the Spokesperson, US Department of Stat. [Last Accessed on 2012 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2012/04/188261.htm .

- 3.Update No. 3, Syria Regional Refugee Response, UNHCR. [Last accessed on 2012 May 3]. Available from: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees .

- 4.Syria Report Humanitarian Aid Operation, Disaster Management Center - Department of Corporate Communication, Turkish Red Crescent Society. [Last Accessed on 2012 Jun 28]. Available from: http://www.kizilay.org.tr/dosyalar/1309847893__040711_ENG_SURIYE_KRIZ_FAALIYET_RAPORU.GENEL.pdf .

- 5.Cronin AA, Shrestha D, Cornier N, Abdalla F, Ezard N, Aramburu C. A review of water and sanitation provision in refugee camps in association with selected health and nutrition indicators – the need for integrated service provision. J Water Health. 2008;6:1–13. doi: 10.2166/wh.2007.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noji , EK , Toole MJ. The historical development of public health responses to disaster. Disasters. 1997;21:366–76. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan MU, Shahidullah M. Role of water and sanitation in the incidence of cholera in refugee camps. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1982;76:373–7. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(82)90194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cronin AA, Shrestha D, Spiegel P, Gore F, Hering H. Quantifying the burden of disease associated with inadequate provision of water and sanitation in selected sub-Saharan refugee camps. J Water Health. 2009;7:557–68. doi: 10.2166/wh.2009.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Custer Coordination Guidance: Guidance for FAO staff working at country level in humanitarian and early recovery operations Publication of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations: Rome. 2010. [Last Accessed on 2012 Jun 28]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/tc/tce/pdf/FAO_Cluster_Coordination_Guidance.pdf .

- 10.3rd ed. Geneva: United Nations Higher Commissioner for Refugees; 2007. Feb, [Last Accessed on 2012 Jun 28]. Handbook of Emergencies. Available from: http://reliefweb.int/node/23398 . [Google Scholar]