Abstract

Background:

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) is a commonly used food additive and there is growing concern that this may play a critical role in the aethiopathogenesis of anovulatory infertility.

Objectives:

The effect of monosodium glutamate (MSG) used as food additive on the ovaries of adult Wistar rat was investigated.

Methods:

Adult female Wistar rats (n=24) weighing between 182 to 186grams were randomly assigned into three groups A, B and C of (n=8) in each group. The treatment groups (A and B) were given 0.04mg/kg body weight and 0.08mg/kg of monosodium glutamate thoroughly mixed with the grower's marsh, respectively on a daily basis. The control group (C); received equal amount of feeds (Growers’ mash) without monosodium glutamate added for fourteen days. The grower's mash was obtained from Edo Feeds and Flour Mill Ltd, Ewu, Edo State and the rats were given water liberally. The rats were sacrificed on day fifteen of the experiment. The ovaries were carefully dissected out and quickly fixed in 10% formal saline for routine histological procedures.

Results:

The histological findings in the treated groups showed evidence of cellular hypertrophy, degenerative and atrophic changes with more severe changes in the group that received 0.08mg/kg of MSG.

Conclusion:

These findings indicate that MSG may have some deleterious effects on the oocytes of the ovaries of adult Wistar rats at higher doses and by extension may contribute to the causes of female infertility. It is recommended that further studies aimed at corroborating these findings be carried out.

Keywords: Monosodium glutamate, histological effect, oocytes, female infertility, vacuolations, ovaries: Wistar rats

Introduction

Pathological processes frequently involve the body's normal responses to abnormal environmental influences. Such harmful peripheral influences as pathogenic micro organisms, trauma, dietary deficiencies and hereditary factors acting alone or in a multifarious interaction with environmental factors, cause diseases.1 A variety of environmental chemicals, industrial pollutants and food additives have been implicated as causing harmful effects.2 Most food additives act either as preservatives, or enhancer of palatability. One such food additive is Monosodium Glutamate (MSG). It is sold in most open market stalls and stores in Nigeria as “Ajinomoto” marketed by West African Seasoning Company Limited; as “Vedan” or “White Maggi” marketed by Mac and Mei (Nig) Limited.

Locally and globally, much controversy has been generated concerning the safety of this product.3 In Nigeria, most communities and individuals often use MSG as a bleaching agent and there is a growing trepidation that its excellent bleaching properties could be harmful to humans and may induce life-threatening ailment in consumers. Despite indication of pessimistic consumer retort to MSG, reputable international organizations and nutritionist have continued to preserve MSG usage, reiterating that it has no undesirable effects in humans.4 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States reports that Monosodium glutamate is harmless and that it should be kept on the “Generally Recognised as Safe” (GRAS)-list of foods. MSG is thus permitted not to be dangerous food additive. As a consequence, it requires no specified daily intake, or an upper limit intake requirement.

The toxic effect of MSG on male reproductive system was substantiated by a study done on the testis of male wistar rats. It was established that it induces oligospermia and increases abnormal sperm morphology in a dose-dependent fashion .4 Furthermore, it has also been documented that MSG causes testicular haemorrhage, degeneration and alteration of sperm cell population and morphology.5

Through its stimulation of the orosensory receptors and by improving the palatability of meals, MSG influences the appetite positively, and induces weight gain.6 Despite its taste stimulation and improved appetite enhancement, reports indicate that MSG is toxic to human and experimental animals.7 Indeed Monosodium glutamate has been implicated in the aetiology of several ailments including epilepsy stroke and depression.8,9

The ovary is a paired, egg-producing reproductive organ found in female organisms. The ovaries also functions in the production of various steroid and peptide hormones like oestrogen and progesterone which sub serve many functions in the reproductive system.10 Abnormality in ovarian function usually leads to anovulatory infertility which constitute a major problem in the contemporary Nigerian society. About 15% of cases of female infertility investigation will show no abnormality. In these cases abnormalities are likely to be present but not detected by current methods.11

This work was carried out to investigate some probable histological effects of MSG on the ovary and its likely involvement in female infertility in Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult female Wistar rats (n=24) weighing between 182 to 186grams were randomly assigned into three groups A, B and C of (n=8) in each group. Groups A and B serve as treatment while C was the control. The rats were obtained and maintained in the Animal Holdings of the Department of Anatomy, School of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Benin, Benin city, Nigeria. They were fed with grower's marsh obtained from Edo feed and flour mill limited, Ewu, Edo state and given water liberally. The rats gained maximum acclimatisation for four weeks before actual commencement of the experiment. The Monosodium glutamate (3g/ sachet containing 99+% of MSG) was obtained from Kersmond grocery stores, Uselu, Benin city.

Monosodium Glutamate Administration

The rats in the treatment groups (A and B) were given 0.04mg/kg body weight and 0.08mg/kg of monosodium glutamate thoroughly mixed with the growers′ mash, respectively on a daily basis. The control group (C); received equal amount of feeds (Growers′ mash) without monosodium glutamate added for fourteen days. The rats were sacrificed on the fifteenth day of the experiment. The ovaries were quickly dissected and fixed in 10% formal saline for routine histological techniques. The 0.04mg/kg and 0.08mg/kg MSG doses were chosen and extrapolated in this experiment based on the the previous work done with the additive.12,13,14 The two doses were thoroughly mixed with fixed amount of feeds (550g-arrived at during the pilot study) in each group.

Histological Study

The tissue were dehydrated in an ascending grade of alcohol (ethanol), cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin wax. Serial sections of 7 microns thick were obtained using a rotatory microtome. The deparaffinised sections were stained routinely with haematoxylin and eosin. Photomicrographs of the desired results were obtained using digital research photographic microscope in the University of Benin research laboratory.

Results

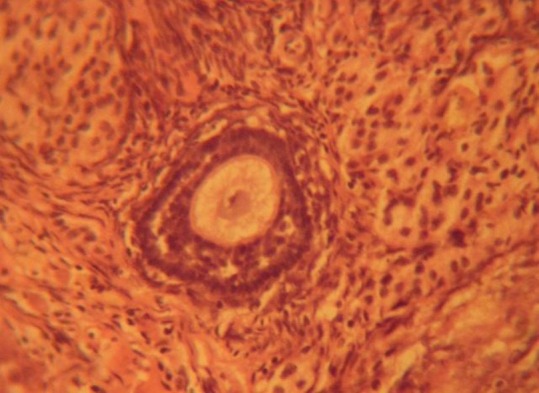

The ovaries of the control group showed normal histological features, illustrating a well defined zona granulosa surrounding the oocyte and compact theca folliculi and the presence of some primordial follicles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Control section of the ovary (Mag. ×400).

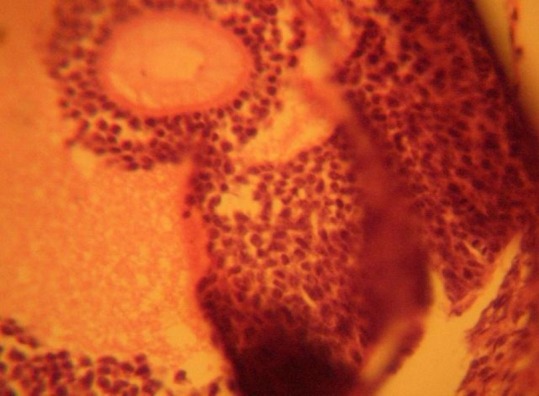

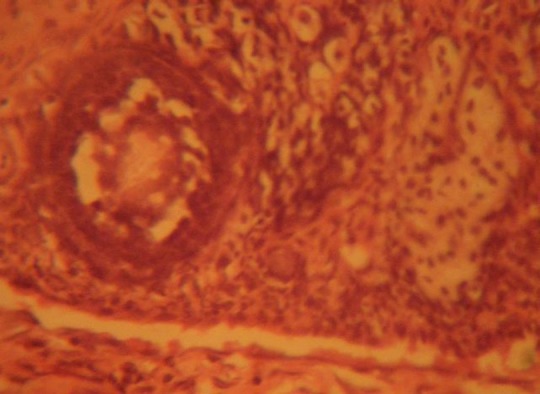

The ovaries of the treated groups showed some cellular hypertrophy of the theca folliculi, complete distortion/destruction of the basement membrane separating the theca folliculi from the zona granulosa. Degenerative and atrophic changes were observed in the oocyte and zona granulosa; these were more pronounced in those that had 0.08mg/kg of MSG mixed in their feed. There were marked vacuolations appearing in the stroma cells (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Treatment section of the ovary that received 0.04mg/kg MSG (Mag. ×400).

Figure 3.

Treatment section of the ovary that received 0.08mg/kg MSG (Mag. ×400)

Discussion

The results of the haematoxylin and eosin staining (H & E) reactions showed some cellular hypertrophy of the theca folliculi, complete distortion/destruction of the basement membrane separating the theca folliculi from the zona granulosa. Degenerative and atrophic changes were observed in the oocyte and zona granulosa; these were more pronounced in those that had 0.08mg/kg of MSG. There were marked vacuolations appearing in the stroma cell.

The increase in cellular hypertrophy of the theca folliculi in the treatment groups as reported in this study may have been as a result of cellular proliferation caused by the improved intake of food which MSG influences.6,7,8 This corroborates the fact that MSG causes an increase in appetite and thereby leading to increase in weight and obesity.8 The vacuolation probably indicates the presence of mucous. Degenerative and atrophic changes which were observed in the oocyte and zona granulosa were more pronounced in the groups treated with higher dose 0.08mg/kg of MSG.

It may be inferred from the present results that higher dose of MSG resulted in degenerative and atrophic changes observed in the ovaries. Degenerative changes have been reported to result in cell death, which is of two types, namely apoptotic and necrotic cell death. These two types differ morphologically and biochemically.12 Pathological or accidental cell death is regarded as necrotic and could result from extrinsic insults to the cell such as osmotic, thermal, toxic and traumatic effects.13 In this experiment MSG could have acted as toxins to the oocyte and follicular cells of the ovaries. The process of cellular necrosis involves disruption of membrane's structural and functional integrity which was also a landmark of this experiment. In cellular necrosis, the rate of progression depends on the severity of the environmental insults.

The greater the severity of insults, the more rapid it is the progression of neuronal injury.14 The principle holds true for toxicological insults to the brain and other organs.15 It may be inferred from the present results that intake of MSG resulted in variable toxic effects on the ovaries with that of higher dose more marked.

This study is limited by the fact that the actual quantity of MSG consumed per day by each rat in the various group could not be actually ascertained, since the substance was mixed with their feeds. Some rats could have consumed more of the MSG than others and this could vary the pathology seen. Another factor was the duration of study (acute) as opposed to chronic which could have yielded more light on the pathology.

The results obtained in this study following the administration of MSG to adult wistar rats demonstrate a dose dependent deleterious effect on the ovaries. Thus MSG may be implicated in the aetiology of anovulatory infertility. It is recommended that further studies, including hormonal assay be carried out to corroborate these findings.18

References

- 1.Allen GH. General pathology. New York: Churchill Livingstone Medical Division Longman; 1987. The genetic basis of diseases; p. 35056. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore KL. Developing Humans. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co. Ltd; 2003. Congenital malformations due to environmental; pp. 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zerasky K. Nutrition and healthy eating; monosodium glutamate: Is it harmful.? [Assessed on 23/12/2010]; Available http://mayoclinic.com . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onakewhor JUE, Oforofuo IAO, Singh SP. Chronic Administration of Monosodium glutamate Induces Oligozoospermia and glycogen Accumulation in Wister rat testes. Africa J Reprod Health. 1998;2(2):190–197. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oforofuo IAO, Onakewhor JUE, Idaewor PE. The effect of Chronic Admin. Of MSG on the histology of the Adult Wister rat Testes. Bioscience Research Communications. 1997;9(2):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers PP, Blundell JE. Umani and appetite: Effects of Monosodium glutamate on hunger and food intake in human subjects. Physiol Behav. 1990;486:801–804. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belluardo M, Mudo G, Bindoni M. Effect of early Destruction of the mouse arcuate nucleus by MSG on age Dependent natural killer activity. Brain Res. 1990;534:225–333. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90132-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samuels A. The Toxicity/Safety of MSG; A study in suppression of information. Accountability in Research. 1999;6(4):259–310. doi: 10.1080/08989629908573933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mozes S, Sefcikova Z. Obesity and changes of alkaline phosphatase activity in the small intestine of 40 and 80-day old rats subjected to early postnatal overfeeding of monosodium glutamate. Physiol Res. 2004;53(2):177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ovary: From Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia. 2007. Jun 8, [Assessed on 12/04/2010]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ovary. 03:04 .

- 11.Infertility. American Society for Reproductive Medicine. [Assessed on 12/04/2010]. Available from: http://www.asrm.org/Patients/faqs.html. (FAQ)

- 12.Eweka AO, Om’Iniabohs FAE. Histological studies of the effects of monosodium glutamate on the small intestine of adult Wistar rat. Electron J Biomed. 2007;2:14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eweka AO, Om ’Iniabohs FAE, Adjene JO. Histological studies of the effects of monosodium glutamate on the stomach of adult Wistar rats. Ann Biomed Sci. 2007;6:45–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eweka AO, Om’Iniabohs FAE. Histological studies of the effects of monosodium glutamate on the Liver of adult Wistar rats. The Internet Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;6 available http://www.ispub.com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_gastroenterology/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyllie AH. Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated and endogenous endonuclease activation. Nature. 1980;284:555–556. doi: 10.1038/284555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farber JL, Chein KR, Mittnacht S. The pathogenesis of irreversible cell injury in ischemia. American Journal of Pathology. 1981;102:271–281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito U, Sparts M, Walker JT, Warzo S. Experimental Cerebral Ischemia in Magolian Gerbils (1). Light microscope observations. Acta Neuropathology. 1975;32:209–223. doi: 10.1007/BF00696570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martins LJ, Deobler JA, Shih T, Anthony A. Cytophotometric analysis of thalami neuronal RNA in some intoxicated rats. Lif Sci. 1984;35:1593–1600. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90358-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]