Abstract

We present a rare case of mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) with a typical presentation of mental retardation and absence of corneal clouding. The purpose of presenting this case report is to highlight the distinctive manifestation of MPS (Hunter's disease) and to provide a concise report of Hunter's disease for medical practitioners with the hope that such information will help identify boys earlier in the course of their disease. This report is of a 7-year-old boy who presented to the children outpatient through a referral with a history of inability to grasp objects, inability to express self, and coarse skin, which started 5 years ago. On examination, he was short statured, with a big head, protruding abdomen, coarse skin, swollen wrist joints, and clubbed fingers. There was mild mental retardation. Investigations revealed mucopolysaccharides in urine ad radiographic findings were in keeping with diagnosis. Based on the clinical features and radiological findings, one can diagnose a case of MPS. However, careful and critical approach is necessary to exactly diagnose the type of MPS as enzymatic studies are not available in most centers.

Keywords: Mucopolysaccharidosis, Children, Distinctive features

Introduction

We present a rare case of mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS). The purpose of presenting this case is to note the distinctive manifestation of MPS type II (Hunter's syndrome).

MPS is a group of metabolic disorders caused by absence or malfunctioning of the lysosomal enzymes needed to break down molecules called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs).[1] Children with MPs either do not produce enough of one of the two enzymes required to break down the sugar chains into proteins and simpler molecules. Over a long period, this GAGs collect in the cells, blood, and connective tissue.[2] They cause permanent progressive cellular damage which affects the appearance of the individual, causing facial dysmorphism, organomegaly, joint stiffness, contractions, pulmonary dysfunction, myocardial enlargement, and neurological impairment. This could result in impaired intelligence.[2]

As there is no effective therapy for MPS type II (Hunter's syndrome), treatment has been mainly palliative.[3] However, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with recombinant humaniduronate-2-sulfatase has been introduced.[3]

We report this typical case of Hunter's syndrome because of its rarity and highlight the distinctive features.

The only known case reported in Nigeria was that of Ogubiyi et al.[4] in Ibadan in 2006 of a 14-year-old male. This condition is a rare one, with a prevalence of 1 in 170,000 cases.[5]

Case Report

A 7-year-old boy presented with inability to hold materials, inability to express self, and coarse skin, 5 years ago. The patient was apparently well until about 5 years ago when he was noticed not to be able to hold materials due to stiffening of the wrist fold. He was also unable to express “self needs” (toilet needs). There was also the problem of talking incoherently and other problems such as protrusion of abdomen and poor height.

The patient then presented to University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) where he was seen and some investigations were demanded. He was later managed in Lagos where the investigations were done.

He was born of an uneventful pregnancy. There was no history of drug ingestion during pregnancy by the mother. Delivery was by spontaneous vertex and he cried immediately after birth. He sat with support at 3 months, crawled at 7 months, walked at 1 year, and cannot express himself even till now, but can say mama and papa. He still bed wets and barely attains bowel control. Still, at this age, the patient cannot bid bye-bye and separate his fingers. Currently, he has not yet enrolled in school. He has received all immunizations to date.

He is the only child in a separated family and is currently staying with his aunt.

On examination, he had a short stature (1 m), with a low upper to lower segment ratio of 1.2 (expected for age is 1.7), big head, protruding abdomen, coarse skin, swollen wrist joints, and clubbed fingers, and he was mildly pale, anicteric, acyanosed, and mildly dehydrated.

Systemic examination showed a distended abdomen, and his liver was 16 cm from xiphisternum which was tender with occipito-frontal circumference of 59 cm (macrocephaly), ridging of the sutures, widened nasal bridge, frontal bossing, capud quadratum, widely spaced teeth, coarse facies, skin thickening, claw and shortened fingers (bradydactyly) with painless nodules.

Other findings showed pectus carinatum and transmitted breath sound with no cardiovascular anomaly.

The clinical photograph of the patient and plain radiographs of patient's vertebrae is shown in Figures 1–5.

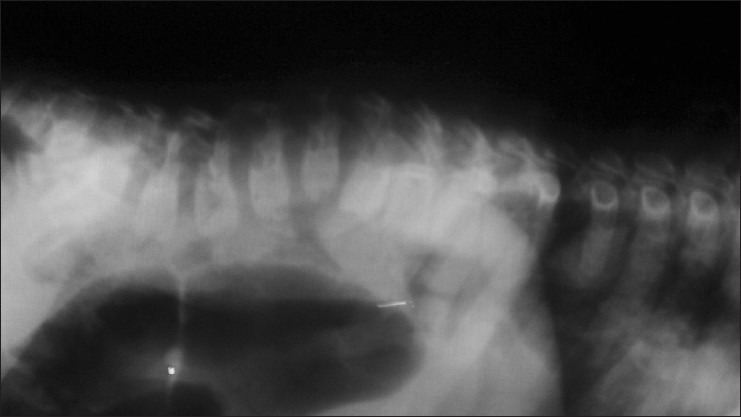

Figure 1.

Radiograph of part of cervical and thoraco-lumbar vertebrae of our patient showing the following: Anterior wedge collapse in the C3 and C4 vertebral bodies; the cervical spine is normal in alignment and density; the disc spaces are within normal limits; spondylolisthesis of the L1 vertebrae over the L2 vertebrae with gibbus formation; anterior wedge collapse of the L2 vertebral body; anterior beaking is noted in the L1–L3 vertebral bodies; and the density of the vertebrae and disc spaces are normal

Figure 5.

Disproportionate short trunk and thick skin

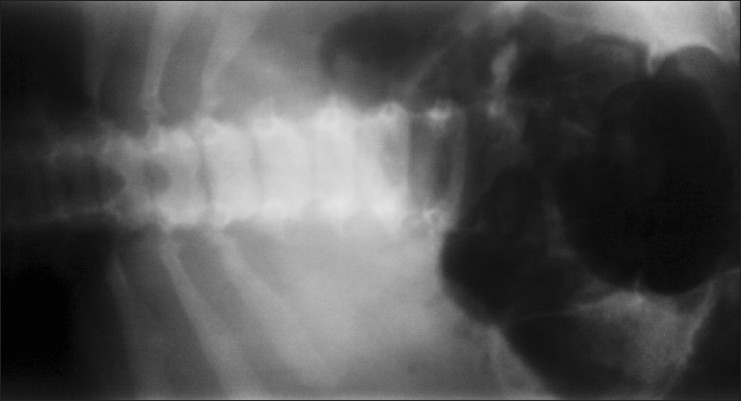

Figure 2.

Radiograph of iliac vertebrae showing tapering of iliac spine with sclerosis (shown by irregular shadows)

Figure 3.

Coarse facies, protuberant abdomen, absence of corneal clouding, and swollen eye lids

Figure 4.

Clawed and short fingers, with nodules on the wrist

Gait was noted to be clumsy and stiff. Range of motion in all extremities was limited, and the arms and legs were slightly flexed.

Intelligence quotient, as determined by “draw a man test,” was in the mild (mental retardation) range.

Investigations revealed the following

Full blood count (FBC) and Serum electrolyte, urea and creatinine (SEUCR) (except for urea) were within normal range for age.

Blood film : Anisopoikilocytosis, microcytosis, hypochromia with pencil cells (showing iron deficiency).

SEUC; urea: 20 mg/dl (2.5–6.4 mg/dl).

Chemistry

Analine exposure

Urinary creatinine: 8.48 mmol/l

Oligosaccharide was present in urine

Urate:creatinine ratio – 0.48 (0.27–0.91)

Urinary mucopolysaccharide – 12.1 mg (0.0–12.9 mg)

Methylene blue analysis was normal in the urine sample.

Discussion

The first case of Hunter's syndrome was reported by Ogubiyi et al.[4] in Ibadan in 2006 of a 14-year-old male who was first seen in dermatology clinic with complaints of bumps and coarse skin. In our study, all the clinical features like short stature, organomegaly, short neck, coarse facial (a feature similar to that reported by Ogubiyi et al.) features, large head, small stubby fingers, mild mental retardation, radiological correlates such as breaking of vertebrae, proximal tapering of metacarpal bones, j-shaped sella turcica, as well as developmental milestone history were all suggestive of Hunter's syndrome.

MPS was first described by Charles Hunter, a Canadian physician, who, in 1917, described a rare disease found in two brothers.[6]

All MPSs are autosomal recessive except Hunter's syndrome which is X-linked recessive.[7] Individuals with this problem have undegraded or partially degraded GAG which accumulates within the lysosomes and is excreted in urine.[7] This accumulation of GAGs in various organs makes the individuals to have a characteristic appearance and are thus called “gargoyles.”[4]

MPS II (Hunter's syndrome) is a rare X-linked disorder caused by a deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme, iduronate-2-sulfatase which catalyzes a step in the catabolism of GASs.[8] This accumulates within tissues and organs, contributing to signs and symptoms of the disease. The accumulated metabolites can also deposit in the renal tubules, leading to obstructive uropathies. This may have attributed to the increase in serum creatinine and urea in our patient. The liver tenderness in our patient could be explained by the fatty degeneration and enzymatic degradation of accumulated mucopolysaccharides in the liver. This is akin to what happens in glycogen storage disease where degeneration of excess glycogen in the liver can cause tender hepatomegaly.[8]

It has a prevalence of 1 in 170,000 males live births.[5] In Nigeria, however, there is no known study to depict the prevalence of Hunter's disease. MPS type II could be mild (type II HB) or severe (Type IIa) depending on the length of survival and the presence or absence of central nervous system (CNS) symptoms.[9] Severe forms occur between 2 and 4 years of age, while the mild form occurs before the age of 10 years.[9] Based on the age of presentation and presence of CNS manifestation, our case is likely of the mild form.

In the milder form, there is mild mental retardation but intelligence is normal, stature is near normal, and clinical features are less obvious.[9] Our patient likely belongs to the mild forms as evidenced by an intelligent quotient of 64% elicited by draw a man test.[10]

Cutaneous features are peculiar to this syndrome and may be the initial manifestation in the mild disease, although patients in both groups may have skin involvement. These findings were ascertained by Demistsu and colleagues[11] and corroborated elsewhere by Ogubuiyi[4] who noted four nodules and bumps in a 14-year-old male with Hunter's disease. Our patient also had bumps and nodules on the wrist.

Rick et al.[12] in Missouri, in their first reported case of Hunter's disease, noted distinct diastolic murmurs. Cardiovascular features like incompetence of the valves, mitral valve prolapse, ischemic heart disease, and cadiomegaly resulting in heart failure were noted in one case by Sonino and co-workers.[13] It is noteworthy that our patient had no cardiac anomaly on careful cardiovascular examination, though this cannot be proven since 2-D echo was not done due to financial constraint.

Another feature that we noted in our patient was sensorineural deafness, determined by examination of the cranial nerve. This finding is very common in almost all cases of Hunter's disease. Young et al.[14] noted sensorineural deafness in majority of their cases.

Diagnosis of the disease is usually by clinical presentation and skeletal survey.[15] This was also highlighted in our patient.

Subjects with Hunter's disease are known to have respiratory problems such as airway obstruction, respiratory failure, and obstructive sleep apnea. These could be explained by the deposition of GAGs in soft tissues.[4] Our patient complained of occasional stridor.

Ophthalmological findings are common in patients with Hunter's disease, though corneal clouding is absent; retinitis pigmentosa, papilledema, and optic atrophy have been noted in some cases.[16] We could not really do a fundoscopy in this patient due to the very brief stay in hospital.

Analysis of GAGs (heparin and dermatan sulfate) is a screening test for mucopolysaccharodisis (MPS) type II; however, this is not diagnostic.[15] Confirmatory diagnosis is by enzyme assay in leukocytes, fibroblasts, or dried blood spots using substrates specific for 12S.[15] Absent or low 12S activity in males is diagnostic of Hunter's syndrome.

Enzyme assay was not done in our patient due to lack of facility, but careful history and prudent physical examination backed with a good radiological investigation will help in making a diagnosis.

ERT using idursulfase, a recombinant human 12S produced in the human cell line, has been reported. Weekly intravenous infusion is given over 3 h at a dose 0.5 mg/kg, diluted in saline.[1]

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT) and umbilical cord blood transplantation (UCBT) are a definitive treatment for MPS.[1] Reports showed reversal of skin changes, hepatomegaly, and cardiovascular complications after transplantation in children, but skeletal changes are irreversible.[4]

Physiotherapy and daily exercise may improve mobility of joints. Our patient did not receive ERT or BMT because of lack of facility.

Consent

A written consent was granted by the care giver.

Limitations

Enzyme assay in leukocytes would help make a definite diagnosis; however, this was not done due to lack of facility. BMT would help the patient to lead a better life; this was not given to our patient due to financial constraint in sending the patient abroad as we do not have such facility here.

Conclusions

MPS is a multisystem disorder which presents with several clinical manifestations. Careful and thorough approach is needed to diagnose the exact type in a low-income country as enzymatic studies are not available. A lot can be done to help individuals with Hunter disease, especially in a resource-poor country like ours, by enrolling them in special schools and physiotherapy and not just neglecting them and leaving them to fate. Again multidisciplinary approach will go a long way to manage the patient wholistically.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the doctors and nurses, who work at the children outpatient clinic, for their cooperation. Our gratitude also extends to the care giver and patient, who were very cooperative. Finally, we thank the almighty god whose assistance and ideas through the course of this work is priceless.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The financial involvements from the conception of this paper to its publication are our responsibility. We have no sponsors.

Conflict of Interest: The authors hereby declare that we have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wraith JE, Scarpa M, Beck M, Bodamer OA, De Meirleir L, Guffon N, et al. Mucopolysacharidosis type II: A clinical review and recommendation for treatment in the era of enzyme replacement therapy. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:267–77. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0635-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin R, Bek M, Eng C, Giughari R, Harmetz P, Mufioz V, et al. Recognition and diagnosis of mucopolysacharidosis II. Pediatrics. 2008;121:377–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gauri S, Tania M, Subodh S. Atypical clinical presentation of mucopolysacharidosis type II: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:154. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogunbiyi A, Adeyinka O, Ogah S, Baiyeroju A. Hunter syndrome: Case report and review of literature. West Afr J Med. 2006;2:169–72. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v25i2.28272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuschi K, Gal A, Paschke E, Kircher S, Bodamer OA. Mucopolysacharidosis type II in females: A case report and review of literature. Pediatr Neuro. 2005;35:270–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter CA. A rare disease in two brothers. Proc R Soc Med. 1917;10:104–16. doi: 10.1177/003591571701001833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarek B. Mucopolysaharidosis. Obtainable at e medicine specialties. [Last assessed on 2011 July 29th] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jurgen S. Mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman EM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadephia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 620–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniele A, Natale P. Hunter syndrome: Presence of material cross reacting with antibodies against idorinate sulfatase. Hum Genet. 1987;75:234–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00281065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alikor AD. Growth and development problem. In: Azubuike JC, Nkanginieme KE, editors. Paediatrics and child health in a tropical region. 2nd ed. Owerri: African Educational Services; 2007. pp. 76–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demistsu T, Kakurai M, Okubo T. Skin eruption as a presenting sign of hunter syndrome. Clin Exp Dematol. 1999;24:179–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.1999.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rick M, Beck M, Roberto G, Paul H, Veronica M, Joseph M. Recognition and diagnosis of mucopolysacharidosis. Am J Pediatr. 2008;121:377–86. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonino V, Sekarski N, Matthieu M, Payout M. Mitral vaive prolapse and type II mucopolysacharidosis. Report of two familial cases. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2001;94:518–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young ID, Harper PS. The natural history of severe form of Hunter's disease: A study based on fifty two cases. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1983;25:481–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1983.tb13794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben S, Bash G, Ziotogora J, Abehovich D. Combined enzymatic and linkage analysis for heterozygote detection in hunters syndrome. Identification of an apparent case of germinal mosaicism. Am J Med Gennet. 1993;47:837–42. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320470608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danis P, Toussant D. Retinal pigmentary changes in mucopolysacharidoses of hunters type. Bull Soc Belg Ophthalmol. 1971;157:365–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]