Summary

Roughly half of all animal somatic cell spindles assemble by the classical prophase pathway, in which the centrosomes separate ahead of nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD). The remainder assemble by the prometaphase pathway, in which the centrosomes separate following NEBD. Why cells use dual pathway spindle assembly is unclear. Here, by examining the timing of NEBD relative to the onset of Eg5-mEGFP loading to centrosomes, we show that a time window of 9.2 ± 2.9 min is available for Eg5-driven prophase centrosome separation ahead of NEBD, and that those cells that succeed in separating their centrosomes within this window subsequently show >3-fold fewer chromosome segregation errors and a somewhat faster mitosis. A longer time window would allow more cells to complete prophase centrosome separation and further reduce segregation errors, but at the expense of a slower mitosis. Our data reveal dual pathway mitosis in a new light, as a substantive strategy that increases both the speed and the fidelity of mitosis.

Introduction

The mitotic spindle is a dynamic, self-assembling protein machine whose main task in the cell is to segregate sister chromatids accurately. Every animal somatic cell spindle assembles by one of two possible pathways: the classical prophase pathway, in which the centrosomes migrate to opposite sides of the nucleus ahead of nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD), or the prometaphase pathway, in which the centrosomes separate after NEBD by a more complex process that includes contributions from kinetochore and cortex-mediated mechanisms (Rattner and Berns, 1976; Rosenblatt, 2005; Rosenblatt et al., 2004; Toso et al., 2009; Waters et al., 1993; Whitehead et al., 1996).

The prophase and prometaphase pathways are not arbitrary points on a continuum of spindle assembly pathways, but are topologically and temporally distinct and genetically separable. In the prophase pathway, the centrosomes migrate to opposite sides of the nucleus ahead of NEBD, so that when rupture of the nuclear membrane occurs, the basic bipolarity of the spindle is already set up, with the chromatid pairs sandwiched between the equivalent poles. In the prometaphase pathway, this is not so: the centrosomes are both on the same side of the chromatin at NEBD, and different mechanisms must be used to assemble a bipolar spindle under conditions in which the component microtubules of the spindle are already interacting with the chromosome arms and the kinetochores. Mechanisms specific to the prometaphase pathway include kinetochore-based mechanisms (Toso et al., 2009), actomyosin-dependent pulling of the poles towards the cell cortex (Rosenblatt, 2005) and chromatin-induced microtubule nucleation (the Ran pathway) (Caudron et al., 2005).

To classify cells as following the prophase or prometaphase pathways, we used a previously-established criterion (Toso et al., 2009) which asks simply, do the chromosomes lie between the two poles at the moment of NEBD? This simple classification serves our present purpose well, because it establishes a prophase pathway population that can be formally compared with all remaining cells, which we classify collectively as prometaphase pathway. Our classification will if anything underestimate any benefits deriving from prophase centrosome separation (see later), because the population of prometaphase pathway cells contains cells with a broad range of intermediate stages of centrosome separation, including for example those that have not begun to separate their centrosomes, and those in which the centrosomes are well separated but in which both centrosomes are nonetheless on the same side of the chromatin at NEBD.

It is clear that mitotic progression is not entirely dependent on centrosome separation, because mitosis, and indeed full development, still occurs in flies lacking centrosomes (Basto et al., 2006). In mammalian somatic cells also, laser ablation of the centrosomes in prophase has been shown not to inhibit bipolar spindle formation (Khodjakov et al., 2000). Nonetheless, centrosome migration in prophase serves to establish the bipolar geometry of the spindle ahead of nuclear envelope breakdown, and it is important to find out why cells do this. We were therefore keen to explore the question, do mitotic progression and mitotic outcome differ between the prophase and prometaphase pathways? Here we have addressed this question by direct live cell imaging of a large number of individual cells.

Results and Discussion

To compare progression and outcomes along the prophase and prometaphase pathways, we established live-cell imaging of a stable HeLa cell line expressing mCherry-α-tubulin (to mark microtubules) and transiently transfected it with full-length human Eg5 (a kinesin-5) tagged with monomeric EGFP (mEGFP) under the control of a low-expressing SV40 promoter. Control measurements from live-cell movies established that ectopic expression of tagged Eg5 does not perturb mitotic progression or bipolar spindle assembly and anaphase onset compared to an empty vector control (Fig. S1). This system allows us to visualise both spindle assembly and the dynamics of Eg5. High resolution live cell imaging shows that Eg5-mEGFP is loaded on to the centrosomes (the incipient spindle poles) in early prophase (Fig. 1A). The loading of Eg5-mEGFP to the centrosomes not only equips them to separate by motor-driven microtubule sliding, but also marks a point in mitotic time very close to the start of the mechanical programme of mitotic spindle assembly. Previous studies using immunofluorescence have shown that the loading of myc-tagged human and Xenopus Eg5 onto centrosomes requires it to be phosphorylated by Cdk1-CyclinB (Blangy et al., 1995; Sawin and Mitchison, 1995). Treatment with roscovitine, a small molecule inhibitor of Cdk1, confirms that both the loading of Eg5-mEGFP to the centrosome, and its continued presence there, are controlled by a roscovitine-sensitive mitotic kinase (Fig. S2). It follows that the instant at which Eg5-mEGFP begins to load to the centrosomes provides a fiducial point in mitotic time, giving us a defined start-point for the process of Eg5-driven centrosome separation, as well as an opportunity to index the timing of subsequent events in mitotic progression, including NEBD. Time lapse tracking of the Eg5-mEGFP signal, subsequent to this start point, reports both the fractional population of Eg5 at the centrosomes, and the position and velocity of the centrosomes as prophase progresses.

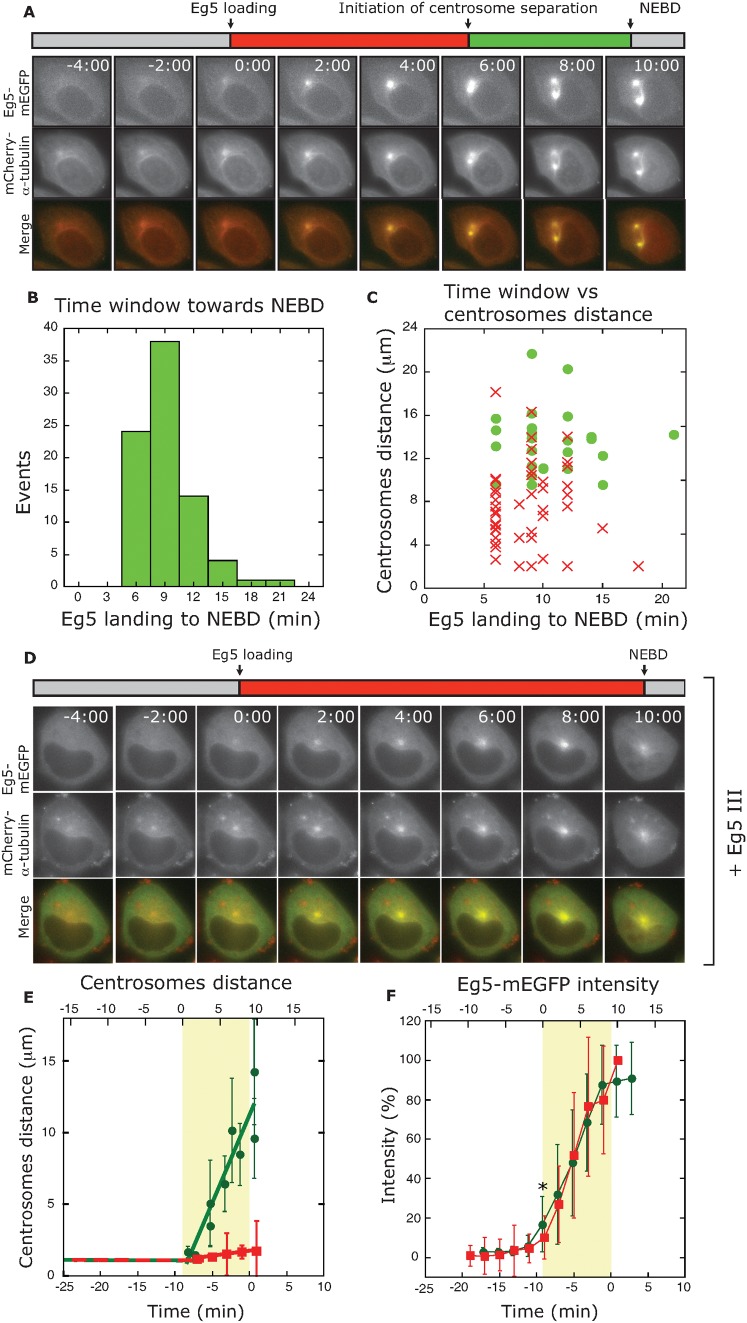

Fig. 1. Eg5 loading to centrosomes indexes the mitotic clock.

(A) Successive views of an mCherry-α-tubulin HeLa cell, transiently expressing Eg5-mEGFP. Images were acquired every 2 min. T=0 is assigned as the first frame in which Eg5 loading becomes detectable. Internal consistency was checked by averaging all sequences, and showed that the corresponding frame in the averaged time-course was the first frame in which the Eg5-mEGFP signal was statistically significantly (P’<0.01) brighter than that in the preceding frame (asterisks in Figure 1A & 1F). Lag time is that between T=0 and initiation of centrosome separation. Translocation time is that between initiation of centrosome separation and NEBD. NEBD, the moment of nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD), delineating the end of prophase, is defined as the first frame in which mCherry-α−tubulin fluorescence is apparent inside the nuclear volume. This cell used the prometaphase pathway; see supplementary video 2. (B) Time window between the onset of Eg5-loading and NEBD. The mean is 9.2±2.9 min (n=82). (C)’Time window duration and centrosomes interdistance are uncorrelated in both the prophase (filled circles) and prometaphase (open circles) pathways, showing that an NEBD countdown timer operates independently of centrosome separation distance. (D) Eg5 loading to centrosomes in the presence of an Eg5-specific small molecule inhibitor (1 µM EI III; conditions as in (A)); see supplementary video 3. Centrosome separation is blocked. (E) Centrosome separation distance versus time in the absence (filled circles) and in the presence (open squares) of EI III. (F) Normalised Eg5-mEGFP intensity on the centrosomes in the absence (filled circles) and presence (open squares) of EI III. All values are shown as mean ± SD. The time window for prophase centrosome separation (yellow boxes) operates identically in the presence of absence of EI III.

Plots of the distance between centrosomes at the time point immediately before NEBD showed no correlation with NEBD onset time (Fig. 1C), strongly suggesting that the mitotic clock controlling NEBD indeed runs entirely independently of Eg5-driven centrosome separation. As a more direct test, we used EI III, an Eg5-specific small molecule inhibitor (dimethylenastron). EI III specifically inhibits the motor domains of Eg5, driving them, like monastrol (Crevel et al., 2004), into a motor. ADP state that binds only weakly to microtubules (Cochran et al., 2005; Crevel et al., 2004; DeBonis et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2004). In wild type cells, and in our stable mCherry-α−tubulin HeLa cell line also, treatment with 1 µM EI III blocks centrosome separation, producing, as expected from previous studies (Gartner et al., 2005; Mayer et al., 1999; Tanenbaum et al., 2008), mono-astral spindles (Fig. 1D,E). Quantitation reveals that whilst 1 µM EI III substantially reduces the total amount of EGFP-Eg5 that loads to the centrosomes (Fig. 1B), it does not affect either the normalized kinetics of loading, or the duration of the interval between the start-point of Eg5 loading and NEBD (Fig. 1F, yellow box). These data confirm that in mitotic Hela cells, the timing of NEBD is uncoupled from the process of Eg5-driven centrosome separation.

Our data indicate that the interlude between the start of Eg5 loading and NEBD is 9.2 ± 2.9 min (mean ± SD; n=82; Fig. 1B). The existence of this time window for kinesin-5-driven centrosome separation suggested to us that cells race to complete centrosome separation ahead of NEBD, and that prophase pathway cells are those that succeed, whilst prometaphase pathway cells are those that fail. To examine which factors determine success or failure, we next asked whether in cells that lose the race to complete prophase centrosome separation (those that go on to use the prometaphase pathway), any individual process in centrosome separation is especially slow and potentially limiting. We measured three parameters, the time-lag between the start of Eg5 loading and the start of centrosome motion (the lag time), the mean duration of centrosome motion (the translocation time), and the mean velocity of centrosome motion.

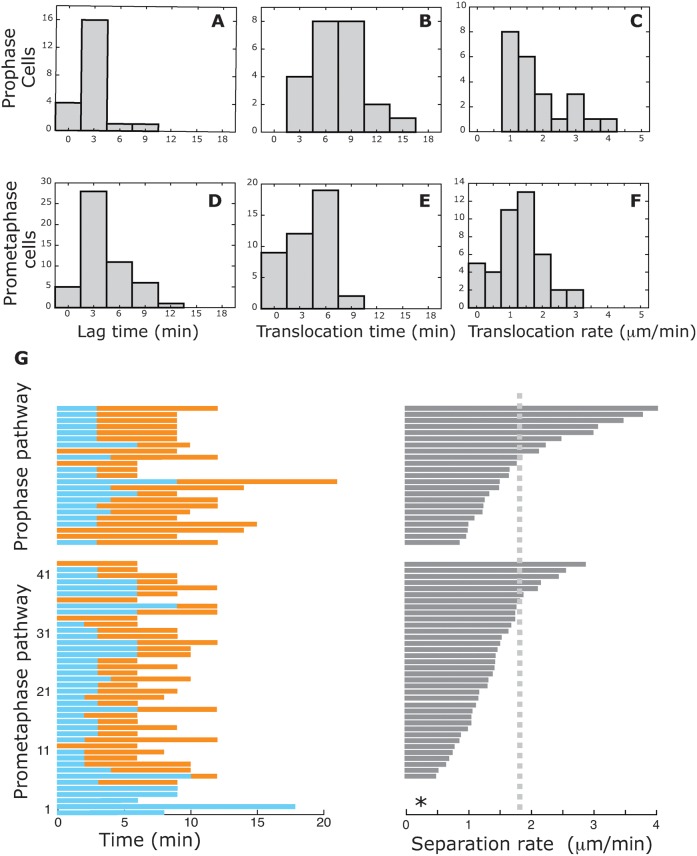

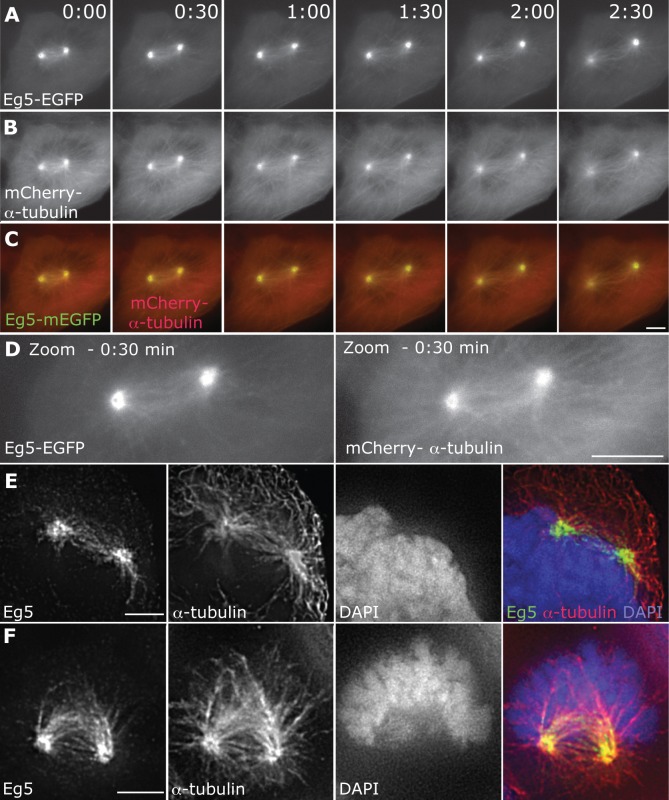

The initial lag reduces the time available for centrosome translocation. The mean initial lag is not significantly different (p<0.01) between prophase (3.0±2.0 min, Fig. 2A) and prometaphase pathway cells (4.1±2.8 min, Fig. 2D). It is possible that this initial lag represents the time required for Eg5 to establish active crosslinks between microtubules issuing from opposite poles. Imaging between the nucleus and the substrate allows visualisation of the evolving antiparallel array of sliding microtubules and supports this idea, in that Eg5-mEGFP is seen to enrich specifically to the overlapped region (Fig. 3A to D; supplementary video 1). Immunofluorescent imaging with anti-Eg5 antibodies and anti-α-tubulin confirm that endogenous Eg5 shows the same localisation pattern (Fig. 3E and F). The translocation time, the mean duration of centrosome migration in prophase, is significantly longer in prophase pathway cells than in prometaphase pathway cells (Fig 2B,E, p<0.0001) . The mean velocity of centrosome separation is also significantly increased in prophase pathway cells (Fig. 2C,F, p<0.01). Individual cell histories (Fig. 2G) reveal no obvious correlations between the lag period, the translocation time and the centrosome velocity, indicating that no individual process is dominantly rate-limiting, but rather that cells that fail to complete prophase pole separation tend to show a longer lag, a lower velocity of centrosome separation and a shorter translocation time.

Fig. 2. Centrosome movement in the prophase and prometaphase pathways.

Lag time (A and D), translocation time (B and E) and centrosome separation rate (C and F) for prophase (A to C) and prometaphase pathways (D to F). Centrosome separation rate was measured only whilst the two centrosomes were moving within the optical plane corresponding to the underside of the nucleus. In the prophase pathway, the mean lag time, translocation time and separation rate are 3.0±2.0 min SD (n=22), 7.4±3.0 min (n=22) and, 1.8±0.9 µm/min (n=23), respectively. In the prometaphase pathway, these parameters are 4.1±2.8 min (n=51), 4.1±2.6 min (n=42) and 1.3±0.7 µm/min (n=43). (G) Individual cell histories for prophase pathway (above) and prometaphase pathway (below) cells. Each horizontal bar represents one cell. Lag time (cyan bar), translocation time (orange bar) and centrosome separation rate (grey bar) are plotted for each cell. The records are shown sorted in order of separation rate. The dotted line shows the average velocity (1.8 µm/min) of prophase pathway cells. Data are mean ± SD.

Fig. 3. Eg5 localizes to anti-parallel microtubules that bridge between the two centrosomes in early prophase.

(A to C) Time course of centrosome separation in an mCherry-α-tubulin HeLa cell transiently transfected with mEGFP-Eg5. Images shown are 30s apart. (A) Eg5-mEGFP, (B) mCherry-α–tubulin and (C) merge. The cell used the prophase pathway. (D) Enlarged views of Eg5-mEGFP and mCherry-α–tubulin at 0:30 min; see supplementary video 4. (E and F) Representative images of HeLa cells in early prophase, fixed and stained with anti-Eg5 antibodies, anti-α –tubulin and DAPI.

Given that centrosome separation in prophase is apparently dispensable, why do cells do it? One possibility is that prophase centrosome separation produces a speed-gain during the subsequent stages of mitosis. Using the initiation of Eg5 loading to the centrosomes as a marker in mitotic time, we find, consistent with previous work (Toso et al., 2009) that prophase pathway cells form bipolar spindles 3–4 min more quickly than prometaphase pathway cells (Fig. 4A). This small time advantage, in a total of ∼30 minutes, might provide a drive towards the prophase pathway. But we suspected a second possibility, that prophase centrosome separation improves the overall fidelity of mitotic chromosome segregation.

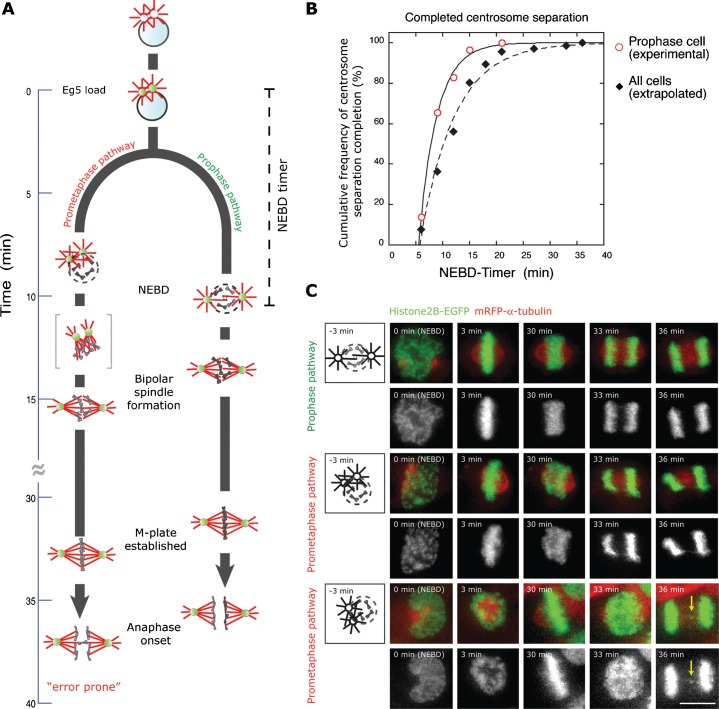

Fig. 4. (A) Schematic of dual-pathway mitosis. The onset of Eg5 loading marks the opening, and NEBD the closure, of a ∼9 minute time window.

Prophase pathway cells succeed in completing centrosome separation within this window; prometaphase pathway cells do not. Prophase pathway cells achieve bipolar spindle formation 3-4 minutes faster than prometaphase pathway cells because they avoid the need to resolve a transient monopolar state (brackets). Prophase pathway cells make at least 3-fold fewer segregation errors than prometaphase pathway cells (B) Cumulative completion of centrosome separation. Open symbols: prophase pathway cells. Centrosome separation completes exponentially, with a rate constant of 0.30 ± 0.02 min−1. Filled symbols: all cells. Centrosome separation completes exponentially with a rate constant of 0.16 ± 0.01 min−1. Data at later time points were calculated by extrapolating a time for completion of centrosome separation based on the measured velocity of centrosome separation prior to NEBD (see Methods). A longer time window would allow more cells to complete prophase centrosome separation, and further reduce segregation errors, but would delay mitosis. A shorter window would drive all cells through the prometaphase pathway, producing more errors. (C) Successive frames from live-cell movies of HeLa cells expressing Histone2B–EGFP/mRFP-α-tubulin that follow either the prophase pathway or prometaphase pathway. Schematic in first column indicates the position of centrosomes at the time point before nuclear envelope breakdown (−3 min). Yellow arrows indicate a lagging chromosome in a prometaphase pathway cell (bottom two rows). Scale bar is 10 µm.

Previous work has shown that if cells are blocked in a monopolar state with Eg5 inhibitors, and then released, there is a concurrent increase in the incidence of segregation errors (Mailhes et al., 2004; Thompson and Compton, 2008), seen as lagging chromosomes during anaphase (Bakhoum et al., 2009). This increased error rate is thought to be a consequence of an increased number of merotelic microtubule-kinetochore attachments, that in turn are caused by the monopolar spindle geometry. However, inhibition-release experiments do not test whether the transient monopolar state (bracketed state in Fig. 4A) that occurs during normal, unperturbed, bipolar spindle formation via the prometaphase pathway also causes an increase in anaphase segregation errors. To test this possibility, we followed mitosis by live cell imaging in a large number of cells and determined firstly whether each cell used the prophase pathway or prometaphase pathway and secondly whether each subsequently made a segregation error (seen as one or more lagging chromosomes) during anaphase. In 3 independent experiments on a total of 1388 mitotic HeLa cells, we found a total of 21 lagging chromosomes (see representative movie frames in Fig. 4C). Of these, a total of 5/685 prophase pathway cells (∼0.7%) showed a lagging chromosome and a total of 16/703 prometaphase pathway cells (∼2.3%) showed a lagging chromosome. These data reveal, crucially, that prophase centrosome separation indeed increases the fidelity of chromosome segregation.

Since prophase centrosome separation increases the fidelity of mitosis, and helps thereby to maintain genome stability, why not send all cells along the prophase pathway? Our data (Fig. 4B) show that prophase centrosome migration completes with roughly exponential kinetics (rate constant = 0.16 min−1, half time = 4.3 mins) so that for 90% of cells to complete centrosome separation before NEBD would require ∼20 minutes, and for 99% to complete, ∼35 minutes. Clearly, improving the success-rate for prophase centrosome separation is desirable, but to do so, cells would need to spend considerably more time waiting for prophase centrosome separation to complete. We speculate that there is an evolutionary drive tending to minimise the overall time spent in mitosis. If so, cells face a dilemma: they can either allow more time for prophase centrosome separation, thereby reducing the mitotic error-rate, or they can reduce the time spent in prophase centrosome separation, tolerate a slightly higher error rate, and complete mitosis faster. As we have shown, cells solve this potential dilemma by requiring that prophase centrosome separation races against a 9.2 minute countdown clock. By using this mechanism, the cell population is split approximately 50∶50 between the prophase and prometaphase pathways and the cells thereby achieve both a substantial overall improvement in the fidelity of chromosome segregation and an appreciable overall acceleration of mitosis (see schematic in Fig. 4A). Were less time to be allocated to prophase centrosome separation, fewer cells would succeed in separating their centrosomes in prophase, and the error rate would increase. Were more time to be allocated to prophase centrosome separation, the error rate would decrease, but the overall time spent in mitosis would be increased. Our data reveal dual-pathway mitosis as a substantive biological strategy that improves both the speed and fidelity of mitosis, thereby reducing the risk of cancer and other genetic diseases.

Materials and Methods

Human HeLa cells were grown as described previously (McAinsh et al., 2006). To generate stable cell lines a pIRESpuro2 vector (Clontech Labratories, Inc) containing mCherry-α-tubulin was constructed (pMC206) and transfected into HeLa cells. Stable clones were selected with 0.4 µg/ml puromycin. To generate mEGFP-tagged Eg5, a PCR fragment of full-length human Eg5 was ligated into pcDNA5/FRT in frame with a carboxy-terminal FLAG-mEGFP epitope tag, under the control of a low-expressing SV40 promotor (pMC207). For live-cell imaging experiments, the mCherry-α-tubulin stable cell line was transiently transfected with this vector and imaged after 24 hours. Live-cell imaging was performed in chambers (Lab-Tek II; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with Leibovitz L-15 medium (Invitrogen) + 10% FCS at 37°C on a wide field Deltavision RT microscope (Applied Precision, LLC) equipped with a CoolSNAP HQ camera (Roper Scientific) with a Sedat filter set (Chroma). For Fig.1 and supp Fig. S2, 3 × 0.7 µm image stacks in 2 colours (FITC / TRITC) were acquired every 2 or 3 mins with a 100× oil NA 1.4 objective. For data in Fig.4 and supp Fig.1, 7 × 2.0 µm image stacks were acquired every 3 mins with a 40 × oil NA 1.3 objective. For imaging at high spatiotemporal resolution (for Fig. 3), two-colour (FITC/TRITC) image stacks (3 × 0.7 µm) were captured every 15 secs for 5 mins.

Immunofluorescence images in 3 colours (DAPI/FITC/TRITC) from fixed HeLa cells (methanol) were acquired with a 100 × oil NA 1.4 objective and deconvolved using SoftWoRx (Applied Precision, LLC). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-Eg5 (1∶1000; Novus Bio) and mouse anti-α-tubulin (1∶1000; Sigma-Aldrich). Secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit-alexa488; 1∶400 and goat anti-mouse-RedX; 1∶400) were from Molecular Probes.

Fluorescent pixel intensity of Eg5-mEGFP was measured using SoftWoRx Explorer (Applied Precision, LLC). Data sets were all normalized to the highest value in a given cell. Data sets were then synchronized using T=0 (the time point at which Eg5–mEGFP was first observed at the centrosome). Pixel intensities for each time point were then averaged and plotted ± standard deviation (S.D.).

To determine velocities of centrosome separation, we used maximum intensity projections of labelled centrosomes, effectively projecting the 3D (geodesic) motions of the centrosomes into a 2D plane. This simplification provides only a rough estimate of the 3D velocities of kinesin-5-driven centrosome migration, but is sufficient to allow us to compare progress and outcomes along the prophase and prometaphase pathways.

Acknowledgments

We thank Frank Kozielski for the kind gift of a human Eg5 cDNA and Patrick Meraldi for the pcDNA5-FRT-FLAG-mEGFP construct. We also thank Catarina Samora and Shona Moore for experiments measuring the error rate in the prophase/prometaphase pathways. We are grateful to Anne Straube for critical reading of the manuscript. Research in the Cross (R.A.C and K.K.) and McAinsh laboratories (A.D.M) is supported by Marie Curie Cancer Care.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Bakhoum S. F., Genovese G., Compton D. A. (2009). Deviant kinetochore microtubule dynamics underlie chromosomal instability. Curr Biol. 19, 1937–1942 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basto R., Lau J., Vinogradova T., Gardiol A., Woods C. G., Khodjakov A., Raff J. W. (2006). Flies without centrioles. Cell. 125, 1375–1386 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blangy A., Lane H. A., d'Herin P., Harper M., Kress M., Nigg E. A. (1995). Phosphorylation by p34cdc2 regulates spindle association of human Eg5, a kinesin-related motor essential for bipolar spindle formation in vivo. Cell. 83, 1159–1169 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90142-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudron M., Bunt G., Bastiaens P., Karsenti E. (2005). Spatial coordination of spindle assembly by chromosome-mediated signaling gradients. Science. 309, 1373–1376 10.1126/science.1115964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran J. C., Gatial J. E., 3rd, Kapoor T. M., Gilbert S. P. (2005). Monastrol inhibition of the mitotic kinesin Eg5. J Biol Chem. 280, 12658–12667 10.1074/jbc.M413140200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crevel I. M., Alonso M. C., Cross R. A. (2004). Monastrol stabilises an attached low-friction mode of Eg5. Curr Biol. 14, R411–412 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBonis S., Simorre J. P., Crevel I., Lebeau L., Skoufias D. A., Blangy A., Ebel C., Gans P., Cross R., Hackney D. D., Wade R. H., Kozielski F. (2003). Interaction of the mitotic inhibitor monastrol with human kinesin Eg5. Biochemistry. 42, 338–349 10.1021/bi026716j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner M., Sunder-Plassmann N., Seiler J., Utz M., Vernos I., Surrey T., Giannis A. (2005). Development and biological evaluation of potent and specific inhibitors of mitotic Kinesin Eg5. Chembiochem. 6, 1173–1177 10.1002/cbic.200500005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodjakov A., Cole R. W., Oakley B. R., Rieder C. L. (2000). Centrosome-independent mitotic spindle formation in vertebrates. Curr Biol. 10, 59–67 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)00276-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Carson J. D., Dhanak D., Jackson J. R., Huang P. S., Lee Y., Sakowicz R., Copeland R. A. (2004). Mechanism of inhibition of human KSP by monastrol: insights from kinetic analysis and the effect of ionic strength on KSP inhibition. Biochemistry. 43, 15258–15266 10.1021/bi048282t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailhes J. B., Mastromatteo C., Fuseler J. W. (2004). Transient exposure to the Eg5 kinesin inhibitor monastrol leads to syntelic orientation of chromosomes and aneuploidy in mouse oocytes. Mutat Res. 559, 153–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer T. U., Kapoor T. M., Haggarty S. J., King R. W., Schreiber S. L., Mitchison T. J. (1999). Small molecule inhibitor of mitotic spindle bipolarity identified in a phenotype-based screen [see comments]. Science. 286, 971–974 10.1126/science.286.5441.971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh A. D., Meraldi P., Draviam V. M., Toso A., Sorger P. K. (2006). The human kinetochore proteins Nnf1R and Mcm21R are required for accurate chromosome segregation. EMBO J. 25, 4033–4049 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattner J. B., Berns M. W. (1976). Centriole behavior in early mitosis of rat kangaroo cells (PTK2). Chromosoma. 54, 387–395 10.1007/BF00292817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt J. (2005). Spindle assembly: asters part their separate ways. Nat Cell Biol. 7, 219–222 10.1038/ncb0305-219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt J., Cramer L. P., Baum B., McGee K. M. (2004). Myosin II-dependent cortical movement is required for centrosome separation and positioning during mitotic spindle assembly. Cell. 117, 361–372 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00341-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawin K. E., Mitchison T. J. (1995). Mutations in the kinesin-like protein Eg5 disrupting localization to the mitotic spindle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 92, 4289–4293 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenbaum M. E., Macurek L., Galjart N., Medema R. H. (2008). Dynein, Lis1 and CLIP-170 counteract Eg5-dependent centrosome separation during bipolar spindle assembly. EMBO J. 27, 3235–3245 10.1038/emboj.2008.242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S. L., Compton D. A. (2008). Examining the link between chromosomal instability and aneuploidy in human cells. J Cell Biol. 180, 665–672 10.1083/jcb.200712029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toso A., Winter J. R., Garrod A. J., Amaro A. C., Meraldi P., McAinsh A. D. (2009). Kinetochore-generated pushing forces separate centrosomes during bipolar spindle assembly. J Cell Biol. 184, 365–372 10.1083/jcb.200809055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters J. C., Cole R. W., Rieder C. L. (1993). The force-producing mechanism for centrosome separation during spindle formation in vertebrates is intrinsic to each aster. J Cell Biol. 122, 361–372 10.1083/jcb.122.2.361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead C. M., Winkfein R. J., Rattner J. B. (1996). The relationship of HsEg5 and the actin cytoskeleton to centrosome separation. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 35, 298–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]