Summary

Vertebrate immune systems are understood to be complex and dynamic, with trade-offs among different physiological components (e.g., innate and adaptive immunity) within individuals and among taxonomic lineages. Desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii) immunised with ovalbumin (OVA) showed a clear trade-off between levels of natural antibodies (NAbs; innate immune function) and the production of acquired antibodies (adaptive immune function). Once initiated, acquired antibody responses included a long-term elevation in antibodies persisting for more than one year. The occurrence of either (a) high levels of NAbs or (b) long-term elevations of acquired antibodies in individual tortoises suggests that long-term humoral resistance to pathogens may be especially important in this species, as well as in other vertebrates with slow metabolic rates, concomitantly slow primary adaptive immune responses, and long life-spans.

Key words: Tortoise, Ectothermic, Innate immunity, Adaptive immunity, Natural antibodies, Epitope masking

Introduction

Trade-offs among components of the vertebrate immune system are a common phenomenon and occur when one portion of the immune system is up-regulated while another portion is down-regulated. Examples of such trade-offs include cell-mediated versus humoral immunity and more generally, innate versus adaptive immunity (Norris and Evans, 2000; Janeway et al., 2005). Factors such as stage of development, reproductive status, and seasonality in behaviour often cause such trade-offs in which one component of the immune system functionally compensates for the loss or reduction of another component. (Norris and Evans, 2000; Salvante, 2006). Recently, Ujvari and Madsen showed that increases in natural antibodies (henceforth NAbs) in water pythons appear to compensate for the immunosenescence of the adaptive immune system due to ageing (Ujvari and Madsen, 2011). Interestingly, such patterns in compensatory trade-offs are usually species specific, and therefore are often not considered in studies of the ecological immunology of non-model organisms (Norris and Evans, 2000; Matson et al., 2006; Salvante, 2006). This failure to take trade-offs into consideration is mostly due to a simple lack of knowledge of the myriad of potential and complex interactions in a species' immune system (Norris and Evans, 2000). However, failure to measure such compensatory interactions may lead to erroneous conclusions in studies of ecological immunology, health, epidemiology of diseases, and evolution of host–pathogen relationships in wild vertebrate populations.

Here, we focus on humoral immunity, or antibody responses, of the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) (Cooper, 1863), because for this species and other threatened and endangered species of testudines (turtles, terrapins, and tortoises), antibody-testing has served as a proxy for infection-status (Herbst et al., 1998; Herbst et al., 2008; Coberley et al., 2001; Jacobson and Origgi, 2007; Sandmeier et al., 2009). In the Mojave population of the desert tortoise, tests for acquired antibodies to one particular pathogen (Mycoplasma agassizii) (Brown et al., 1994) influence important conservation decisions, including prioritising habitat for preservation and the fate of translocation programs (Sandmeier et al., 2009; U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Revised Recovery Plan for the Mojave Population of the Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii), 2011 (http://ecos.fws.gov/tess_public/TESSWebpageRecovery?sort = 1)).

Recent studies in ecological immunology have stressed the importance of examining “innate”, or constitutive, immunity, in addition to acquired immunity in vertebrates (Matson, 2006; Salvante, 2006; Martin et al., 2008). Constitutive immune mechanisms may be more important to ectothermic vertebrates due to their slow metabolic rates and their relatively slow acquired immune responses of low magnitude (Hsu, 1998; Bayne and Gerwick, 2001; Chen et al., 2007). Importantly, the nature of trade-offs between constitutive and acquired components of the immune system may differ between ectothermic and endothermic lineages of vertebrates.

Here, we consider the influence of one component of constitutive immunity, NAbs, on the production of acquired antibodies in desert tortoises. Desert tortoises have recently been shown to have relatively high levels of NAbs to M. agassizii, and levels of these NAbs to this pathogen appear to vary significantly among individuals (Hunter et al., 2008; Sandmeier et al., 2009). Unlike acquired antibodies, NAbs are encoded in the genome (Kantor and Herzenberg, 1993; Baccala et al., 1989; Casali and Notkins, 1989; Baumgarth et al., 2005), are mainly of the IgM isotype (Casali and Schettino, 1996; Baumgarth et al., 2005), and are thought to be an important component of innate immunity against infectious agents (Briles et al., 1981; Szu et al., 1983; Ochsenbein et al., 1999; Baumgarth et al., 2000; Baumgarth et al., 2005; Sinyakov et al., 2002).

As in other species, NAbs in tortoises historically have been ignored as “non-specific background noise” in immunological assays (Schumacher et al., 1993; Brown et al., 1994; Sandmeier et al., 2009). However, NAbs may either enhance acquired immune responses (Ehrenstein et al., 1998; Boes, 2000; Ochsenbein and Zinkernagel, 2000) or in other cases, reduce acquired immune response through the process of epitope masking (Madsen et al., 2007; Parmentier et al., 2008; Ujvari and Madsen, 2011).

Here, we describe the humoral response in the desert tortoise to immunisation with ovalbumin (OVA). OVA is an immunogenic protein of moderate size, known to stimulate B-cells and produce strong antibody responses in vertebrates (Parslow, 2001). We were able to quantify levels of NAbs to OVA by measuring levels of antibody prior to OVA-exposure, as all tortoises have some level of NAbs that bind to OVA (F.C. Sandmeier, Immunology and Disease in the Mojave Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii), PhD thesis, University of Nevada, Reno, 2009). Specifically, we assessed (1) levels of NAbs to OVA of individual tortoises with respect to season and gender, (2) the interaction between levels of natural and acquired antibodies upon immunisation with OVA, and (3) long-term elevations in acquired antibodies more than a year after the animals' exposure to OVA.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

Twenty captive, adult desert tortoises were used in this experiment. All tortoises had been reared in captivity for 15–20 years, and all had neither any known infections nor exposure to wild tortoises. Sixteen tortoises were each given two 0.5 ml intradermal injections (one in each forelimb) of OVA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) in Ribi's adjuvant (Ribi ImmunoChem Research, Inc., Hamilton, Montana, USA). Because brumation, or winter dormancy in reptiles, is known to influence immunisation in testudines (Ambrosius, 1976), eight tortoises were immunised in November 2005 prior to brumation (winter-immunised group), and eight were immunised in April 2006 after brumation (spring-immunised group). Treatment groups in both winter and spring had equal numbers of females and males. A blood sample was taken from each animal prior to treatment to establish each individual's NAb titre and to calculate relative increases in each animal's acquired antibodies. Hence, these samples were used as individual controls in statistical analyses.

As a procedural control, an additional four tortoises were treated equivalently, except they were given injections of sterile saline solution in lieu of OVA/Ribi's adjuvant. Due to this small sample size, constrained by the availability of adult (>10 years in age), captive-raised tortoises, these procedural controls are only depicted visually in our results, and are not included in statistical analyses.

Animal husbandry and sampling

Tortoises were housed at the University of Nevada, Reno (USA), were fed a diet of alfalfa and green vegetables several times weekly, and once weekly offered water for hydration in a tub of shallow water. Brumation (at 13°C) was gradually induced in December, and animals were allowed to brumate for one and a half months. One spring-immunised female was removed from the experiment during the course of treatments due to a decline in health. Two additional animals were not available for blood collection one year later.

Blood samples (2 ml) were drawn from the subcarapacial sinus (Hernandez-Divers et al., 2002) prior to immunisation in November 2005. After immunisation, 0.5–1.0 ml of blood was taken every two weeks until September 2006 (for the winter-immunised group), and until November 2006 (for the spring-immunised group). A final blood sample was taken from all animals approximately one year after the last immunisation treatment, in August 2007, 16 and 14 months after immunisation for the winter and spring immunised groups, respectively. All blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes and centrifuged, and plasma was frozen at −30°C. All work was conducted in accordance with permits issued by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (A06/07-49) and the Nevada Division of Wildlife (S33080). Because the tortoise antibody response was consistently slower than we had estimated at the outset of the experiment, only the pre-immunisation, 27-week post-immunisation, and 12/14 months post-immunisation samples were used in statistical analyses of humoral responses. However, we used a subset of known positive and negative samples from across the time-frame of the experiment to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA titres are both a measure of the amount of antibody and its affinity for the antigen, OVA. OVA-specific antibody titres present in frozen blood plasma samples were assayed using a slightly modified version of the polyclonal ELISA, described in detail by Hunter et al. (Hunter et al., 2008). Briefly, Immulon IB 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) were coated with 50 µl per well of OVA in PBS (10 µg/µl). Plates were incubated overnight at 4°C and washed four times with PBS. Wells were blocked with 200 µL of a 5% non-fat dry milk PBS solution and incubated for 2 hr at 4°C. Plates were washed four times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T). Subsequent washes were performed in the same manner. 1:10, 1:100, 1:1,000, and 1:10,000 dilutions of tortoise plasma were made in PBS-T, 50 µl of which was added to each well, and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed and 50 µl of a 1:10,000 dilution of polyclonal rabbit anti-tortoise Ig reagent (heavy and light chain reactive) (Hunter et al., 2008) were added to each well and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Plates were washed, and 50 µL of goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Zymed, San Francisco, California, USA) was added at a 1:5,000 dilution to each well and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Plates were washed, and 50 µL of the TMB Microwell Peroxidase Substrate System (KPL, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA) was added to each well. Plates were incubated for 20–25 min at room temperature, and 50 µL of 1 N hydrochloric acid was added to each well to stop the reaction. Optical density was read at 405 nm using a Spectra-Max micro-ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, Hercules, California, USA). End-point titres (at a cut-off value of 1.0) were calculated for each sample by plotting dilution versus absorbance (OD) using a best-fit line to approximate the linear portion of each resultant curve at a cut-off value of 1.0 OD.

To adjust for the small variability among ELISA plates, one standard sample of tortoise plasma, serially diluted to match experimental samples, was run on each ELISA plate. Additional controls to test for cross-reactivity of the reagents (anti-tortoise polyclonal rabbit antibody and anti-tortoise goat antibody) were run on each plate. Neither reagent interacted with the OVA antigen under the conditions of the assay.

Statistical analyses

To standardize our results with those from previous studies on reptilian immunology (i.e., the rule-of-thumb of using a 3-fold increase as a positive antibody response (Origgi, 2007)), we primarily ran our analyses on proportional responses in OVA-specific antibodies (Ab titre/NAb titre of that animal). However, to avoid spurious results due to comparing two ratios (Packard and Boardman, 1999), in those analyses we instead used the increase in antibody titres (Ab titre – NAb titre of that animal). Non-parametric statistics (Mann-Whitney U tests and Spearman rank-correlations) were used because our samples had unequal variances, likely exacerbated by unavoidably small sample sizes. We used a significance level of α = 0.05, and all statistical analyses were run in Aabel (Aabel 3, Gigawiz Ltd. Co.).

Results

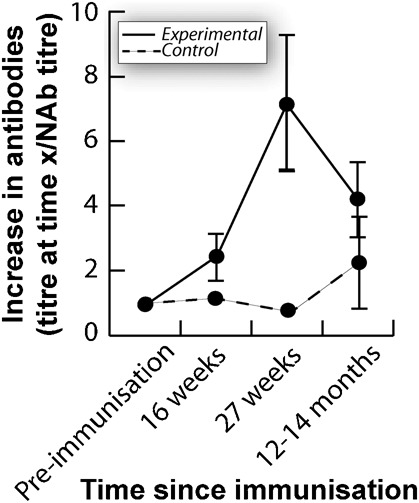

All tortoises exhibited a minimum lag time of four weeks in exhibiting any increase in antibody titres (Ab titre post-treatment/NAb of that animal) and only produced consistent, maximum antibody titres at 27 weeks post-treatment (Fig. 1). In addition, there was no measurable drop in antibody titres during the year (spring through fall, 2006) in which the experiment was run (Fig. 1). We calculated a sensitivity of 0.94 and specificity of 0.98, based on other known positive and negative samples from these same animals.

Fig. 1. Mean proportional increases in OVA-specific antibody titres versus time after primary immunisation.

Standard deviations around the mean are shown for both experimentally-immunised tortoises (n = 16) and procedural control animals (n = 4). Due to variable levels of pre-immunisation NAbs to OVA among animals, the proportional increase in antibodies for each animal is (Ab titre at time x)/(pre-immunisation NAb titre).

All tortoises had relatively high levels of NAbs to OVA. NAb titres in the winter were significantly lower than NAb titres in the spring (n = 8) (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U: Z = −1.890; p = 0.029). Gender did not influence NAb titres (males (n = 8), females (n = 8); two-tailed Mann-Whitney U: Z = −0.105; p>0.5).

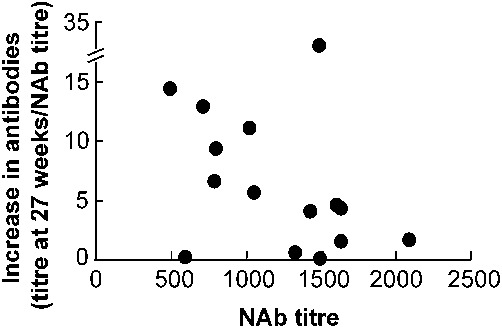

Maximum titres of acquired antibodies were significantly elevated over pre-immunisation NAb titres (n = 15; one-tailed Mann-Whitney U: Z = −2.883; p = 0.002) (Fig. 1). A significant, negative relationship existed between an animal's NAb titres and its maximum, acquired antibody response (n = 14; minus outlier) (Spearman's rank correlation: rs = −0.52, p (one-tailed) = 0.028) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Relationship between each tortoise's maximum, increase in OVA-specific antibody titres at week 27 [(Ab titre at week 27)/( NAb titre pre-immunisation)] versus the animal's NAb titre pre-immunisation.

Animals with high NAb titres showed significantly smaller increases in antibodies due to immunisation (minus outlier: rs = −0.52, p = 0.028).

Antibody titres more than one year post-treatment (n = 14) were significantly higher than pre-immunisation antibody titres (one-tailed Mann-Whitney U: Z = −2.895; p = 0.002) (Fig. 1). Maximum increases in antibody titre (antibody titre at 27 weeks post-immunisation – NAb titres; n = 14) were positively correlated with titre increases one year post-treatment (antibody titres 12 or 14 months post-immunisation – NAb titres) (Spearman's rank correlation (minus outlier): rs = 0.725; p (one-tailed) = 0.003). Of these re-sampled tortoises, seven out of nine tortoises still tested positive for acquired antibodies to OVA 12–14 months after immunisation.

Discussion

We found three prominent patterns not previously described in desert tortoises. Some of these patterns, mainly the negative relationship between NAbs and the acquired antibody response, have only been described in a small number of other species (e.g., Parmentier et al., 2008; Ujvari and Madsen, 2011). These patterns included (1) high levels of NAb to OVA, with high variability among individuals (Fig. 2), (2) a negative relationship between NAb titres and the production of acquired antibodies (Fig. 2), and (3) a prolonged time period during which acquired antibody levels remained elevated (Fig. 1).

Interestingly, titres of NAbs to OVA were not equally high in all tortoises, and even within our sample of 16 tortoises there was a large amount of individual variation in NAb titres. Large individual variation in ecologically-significant levels of NAbs also have been reported in humans, mice, birds, and fish (Ben-Aissa-Fennira et al., 1998; Sinyakov et al., 2002; Parmentier et al., 2004; Kachamakova et al., 2006). Due to the inherent polyspecificity of NAbs, we hypothesise that high NAb levels to OVA in tortoises may indicate high levels of NAbs to actual pathogens and greater resistance to pathogenic disease (Gonzalez et al., 1988; Flajnik and Rumfelt, 2000; Baumgarth et al., 2005). For example, chickens with high titres of NAbs to an artificial antigen (sheep red blood cells) tended to have high titres to a variety of other antigens (Parmentier et al., 2004). Combined with the (often) protective nature of NAbs against pathogens (Briles et al., 1981; Cartner et al., 1998; Baumgarth et al., 2000; Sinyakov et al., 2002), the individual variation in NAbs measured in this study could very well be important in ecological and evolutionary dynamics of disease in wild tortoise populations. However, with the exclusion of M. agassizii (Hunter et al., 2008), little is known about the reactivity of the desert tortoise NAb repertoire to a variety of pathogens.

The negative relationship between NAb titres and the magnitude of the acquired antibody response (Fig. 2) suggests that NAbs may have had a biological effect through epitope masking. Epitope masking refers to the binding of antigen (the substance recognized as “foreign” by the immune system) by constitutive molecules, such as NAbs, which then reduce the amount of “free” antigen and the magnitude of the subsequent acquired response (Janeway et al., 2005). For example, in fish, there appears to be a general negative relationship between levels of NAbs and levels of acquired antibody produced in response to vaccinations (Sinyakov et al., 2002; Sinyakov et al., 2006; Sinyakov and Avtalion, 2009). The failure of water pythons (Liasis fuscus) to make an acquired antibody response to immunisations was attributed to such a masking function of NAbs (Madsen et al., 2007). Furthermore, water pythons showed an increase in NAbs with age, which correlated with a reduction in the acquired immune response with age, also attributed to the effect of epitope masking (Ujvari and Madsen, 2011). Thus, NAbs may provide protection against pathogens, with high levels lowering the need for the acquired immune system to mount a response.

Just as the tortoises' acquired antibody titres to OVA remain conspicuously elevated for over a year, likewise persistent antibody responses have been observed in other vertebrates and may be an especially common phenomenon in ectothermic vertebrates. For example, Herbst et al., observed a long-lived antibody response in two individuals of green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), which had elevated IgY levels for at least 20 months after experimental infection with chelonid fibropapillomatosis-associated herpes virus (Herbst et al., 2008). Long-lived, antibody-secreting cells have been observed in the bone marrow of mammals and the anterior kidney of fish and function to produce antibodies for months to years (Slifka et al., 1995; Slifka and Ahmed, 1996; Manz et al., 1998; Kaattari et al., 2005). For example, in rainbow trout (Oncorhyncus mykiss), long-lived B-cells are activated by antigen, migrate to the anterior kidney, and produce all or most of the circulating levels of antibody present in the late humoral response (Bromage et al., 2004; Kaattari et al., 2005).

Kaattari et al. suggest that long-lived, antibody-secreting plasma cells may be responsible for the arithmetic (versus geometric) increases in antibody titre often observed upon secondary exposure to antigens in fish (Kaattari et al., 2005). Arithmetic increases in antibody titre are also commonly observed in reptiles (Ambrosius, 1976; Jacobson and Origgi, 2007; Origgi, 2007) and also may be associated with long-lived, antibody-secreting plasma cells. While desert tortoises may possess long-lived plasma cells that produce antibodies for extended periods, the half-lives of desert tortoise immunoglobulins have not, to our knowledge, been evaluated or reported. Therefore, the persistence of high titres of acquired antibodies could also be due to persistent antibody molecules with extremely long half-lives in addition to, or instead of, long-lived plasma cells.

It is likely advantageous to ectothermic vertebrates with low metabolic rates and slow humoral immune responses to retain persistent antibodies to ensure some resistance to previously encountered pathogens. Indeed, reptiles are known to have very slow primary humoral responses, which develop within four to six weeks instead of the four to six days typical of mammalian responses (Zimmerman et al., 2010; Janeway et al., 2005). Such a slow response calls into question its efficacy, given the potential for the growth of pathogens to out-pace the immune system. However, persistent antibodies provide insurance of protection against secondary exposure to a pathogen, much like NAbs provide protection against common pathogens that an individual is likely to encounter in its lifetime. We hypothesize that both long-term, acquired antibodies and NAbs provide reptiles with necessary protection from infections without the need for the animal to wait for the protection provided by a secondary, or even a primary, humoral response.

In addition, once the reptile mounts a primary humoral response, it tends to be of a relatively low magnitude in comparison to mammalian responses (Hsu, 1998). For example, our immunisation of tortoises with OVA produced a maximum, primary humoral response of a 20- to 30-fold increase in antibody titres (Fig. 1). In contrast, mammals usually respond to such an immunisation with OVA with 100-fold increase in antibody titres (Leishman et al., 1998; Parslow, 2001). However, the true value of the slow, low-magnitude antibody response of reptiles may be in the protection it provides against the same pathogen in the future.

Our findings also have practical implications for the conservation of Testudines that likely can be expanded to other ectothermic vertebrates. Most species of Testudines (especially those in the Testudinidae; tortoises) are considered to warrant special conservation concern and protection, as many populations are declining globally; see the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, version 2012.1 (http://www.iucnredlist.org), downloaded on 20 August 2012. Diseases of Testudines are often cryptic, and serological tests for quantifying pathogen-specific antibodies have been widely used to indicate the disease-status of both individuals and populations (Herbst et al., 1998; Herbst et al., 2008; Coberley et al., 2001; Jacobson and Origgi, 2007; Sandmeier et al., 2009). Levels of NAbs or long-term elevations in acquired antibodies due to past exposure have seldom been considered in these assessments (but see Hunter et al., 2008). Given our results demonstrating a potential trade-off between NAb levels and acquired humoral immune responses, NAb titres should be included in analyses of acquired antibody titres to assess whether epitope-masking might be reducing the acquired response.

The quantification of NAbs is needed to expand our knowledge of the immune system of the tortoises, other ectothermic vertebrates, and other vertebrates in general. Understanding the interactions between constitutive and acquired immunity (as well as possibly interacting factors such as the roles played by seasonality, ambient temperature, gender, breeding condition, and metabolic rates), will lead to a better understanding of the biology and ecology of host-pathogen interactions in ectothermic vertebrates. Furthermore, a more complete understanding of the full array of constitutive, and acquired, parameters in the reptilian immune system would allow for increased accuracy in diagnosing levels of pathogen exposure as well as host resistance in natural populations. The evolutionary significance of a greater reliance on constitutive versus acquired immune parameters in reptiles has not been adequately explored, but such research will likely provide insights into current and past pathogen pressures, life history trade-offs in reptiles, and the evolution of the vertebrate immune system.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Gray for his invaluable assistance, both with the collection of blood samples and various technical and logistic aspects of this project. We also thank Michael Teglas, four anonymous reviewers, and the UNR EECB peer review group for revisions on an earlier draft of this manuscript. The work was conducted under a protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Nevada, Reno (IACUC A06/07-49). Supplementary data are available upon request from F.C. Sandmeier. This work was funded by a grant from the Desert Conservation Program of Clark County, Nevada (2005-UNR-567-P).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Ambrosius H. (1976). Immunoglobulins and antibody production in reptiles. Comparative Immunology (ed. Marchalonis J J.), pp. 298–334 New York: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Baccala R., Quang T. V., Gilbert M., Ternyck T., Avrameas S. (1989). Two murine natural polyreactive autoantibodies are encoded by nonmutated germ-line genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 4624–4628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarth N., Herman O. C., Jager G. C., Brown L. E., Herzenberg L. A., Chen J. (2000). B-1 and B-2 cell-derived immunoglobulin M antibodies are nonredundant components of the protective response to influenza virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 192, 271–280 10.1084/jem.192.2.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarth N., Tung J. W., Herzenberg L. A. (2005). Inherent specificities in natural antibodies: a key to immune defense against pathogen invasion. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 26, 347–362 10.1007/s00281-004-0182-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayne C. J., Gerwick L. (2001). The acute phase response and innate immunity of fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 25, 725–743 10.1016/S0145-305X(01)00033-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben–Aissa–Fennira F., Ben Ammar–El Gaaied A., Bouguerra A., Dellagi K. (1998). IgM antibodies to P1 cytoadhesin of Mycoplasma pneumoniae are part of the natural antibody repertoire expressed early in life. Immunol. Lett. 63, 59–62 10.1016/S0165-2478(98)00053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes M. (2000). Role of natural and immune IgM antibodies in immune responses. Mol. Immunol. 37, 1141–1149 10.1016/S0161-5890(01)00025-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briles D. E., Nahm M., Schroer K., Davie J., Baker P., Kearney J., Barletta R. (1981). Antiphosphocholine antibodies found in normal mouse serum are protective against intravenous infection with type 3 streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Exp. Med. 153, 694–705 10.1084/jem.153.3.694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromage E. S., Kaattari I. M., Zwollo P., Kaattari S. L. (2004). Plasmablast and plasma cell production and distribution in trout immune tissues. J. Immunol. 173, 7317–7323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. B., Schumacher I. M., Klein P. A., Harris K., Correll T., Jacobson E. R. (1994). Mycoplasma agassizii causes upper respiratory tract disease in the desert tortoise. Infect. Immun. 62, 4580–4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartner S. C., Lindsey J. R., Gibbs–Erwin J., Cassell G. H., Simecka J. W. (1998). Roles of innate and adaptive immunity in respiratory mycoplasmosis. Infect. Immun. 66, 3485–3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali P., Notkins A. L. (1989). CD5+ B lymphocytes, polyreactive antibodies and the human B-cell repertoire. Immunol. Today 10, 364–368 10.1016/0167-5699(89)90268-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali P., Schettino E. W. (1996). Structure and function of natural antibodies. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 210, 167–179 10.1007/978-3-642-85226-8_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Cuijuan N., Pu L. (2007). Effects of stocking density on growth and non-specific immune responses in juvenile soft-shelled turtle Pelodiscus sinensis. Aquaculture Research 38, 1380–1386 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2007.01813.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coberley S. S., Herbst L. H., Ehrhart L. M., Bagley D. A., Hirama S., Jacobson E. R., Klein P. A. (2001). Survey of Florida green turtles for exposure to a disease-associated herpesvirus. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 47, 159–167 10.3354/dao047159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J. G. (1863). Description of Xerobates agassizii. Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci. 2, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenstein M. R., O'Keefe T. L., Davies S. L., Neuberger M. S. (1998). Targeted gene disruption reveals a role for natural secretory IgM in the maturation of the primary immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10089–10093 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flajnik M. F., Rumfelt L. L. (2000). Early and natural antibodies in non-mammalian vertebrates. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 252, 233–240 10.1007/978-3-642-57284-5_24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R., Charlemagne J., Mahana W., Avrameas S. (1988). Specificity of natural serum antibodies present in phylogenetically distinct fish species. Immunology 63, 31–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst L. H., Greiner E. C., Ehrhart L. M., Bagley D. A., Klein P. A. (1998). Serological association between spirorchidiasis, herpesvirus infection, and fibropapillomatosis in green turtles from Florida. J. Wildl. Dis. 34, 496–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst L. H., Lemaire S., Ene A. R., Heslin D. J., Ehrhart L. M., Bagley D. A., Klein P. A., Lenz J. (2008). Use of baculovirus-expressed glycoprotein H in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay developed to assess exposure to chelonid fibropapillomatosis-associated herpesvirus and its relationship to the prevalence of fibropapillomatosis in sea turtles. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15, 843–851 10.1128/CVI.00438-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez–Divers S. M., Hernandez–Divers S. J., Wyneken J. (2002). Angiographic, anatomic and clinical technique descriptions of a subcarapacial venipuncture site for chelonians. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 12, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu E. (1998). Mutation, selection, and memory in B lymphocytes of exothermic vertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 162, 25–36 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1998.tb01426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter K. W., Jr, Dupré S. A., Sharp T., Sandmeier F. C., Tracy C. R. (2008). Western blot can distinguish natural and acquired antibodies to Mycoplasma agassizii in the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii). J. Microbiol. Methods 75, 464–471 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson E. R., Origgi F. C. (2007). Serodiagnostics. Infectious Diseases And Pathology Of Reptiles (ed. Jacobson E R.), pp. 381–394 New York: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Janeway C. A., Jr, Travers P., Walport M., Schlomick M. J. (2005). Immunobiology: The Immune System In Health And Disease, 6th edition. New York: Garland Science. [Google Scholar]

- Kaattari S., Bromage E., Kaattari I. (2005). Analysis of long-lived plasma cell production and regulation: implications for vaccine design for aquaculture. Aquaculture 246, 1–9 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.12.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kachamakova N. M., Irnazarow I., Parmentier H. K., Savelkoul H. F. J., Pilarczyk A., Wiegertjes G. F. (2006). Genetic differences in natural antibody levels in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 21, 404–413 10.1016/j.fsi.2006.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor A. B., Herzenberg L. A. (1993). Origin of murine B cell lineages. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11, 501–538 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.002441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leishman A. J., Garside P., Mowat A. M. (1998). Immunological consequences of intervention in established immune responses by feeding protein antigens. Cell. Immunol. 183, 137–148 10.1006/cimm.1998.1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen T., Ujvari B., Nandakumar K. S., Hasselquist D., Homdahl R. (2007). Do “infectious” prey select for high levels of natural antibodies in tropical python? Evol. Ecol. 21, 271–279 10.1007/s10682-006-9004-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manz R. A., Löhning M., Cassese G., Thiel A., Radbruch A. (1998). Survival of long-lived plasma cells is independent of antigen. Int. Immunol. 10, 1703–1711 10.1093/intimm/10.11.1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L. B., Weil Z. M., Nelson R. J. (2008). Seasonal changes in vertebrate immune activity: mediation by physiological trade-offs. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 321–339 10.1098/rstb.2007.2142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson K. D. (2006). Are there differences in immune function between continental and insular birds? Proc. Biol. Sci. 273, 2267–2274 10.1098/rspb.2006.3590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson K. D., Cohen A. A., Klasing K. C., Ricklefs R. E., Scheuerlein A. (2006). No simple answers for ecological immunology: relationships among immune indices at the individual level break down at the species level in waterfowl. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273, 815–822 10.1098/rspb.2005.3376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris K., Evans M. R. (2000). Ecological immunology: life history trade-offs and immune defense in birds. Behav. Ecol. 11, 19–26 10.1093/beheco/11.1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsenbein A. F., Zinkernagel R. M. (2000). Natural antibodies and complement link innate and acquired immunity. Immunol. Today 21, 624–630 10.1016/S0167-5699(00)01754-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsenbein A. F., Fehr T., Lutz C., Suter M., Brombacher F., Hengartner H., Zinkernagel R. M. (1999). Control of early viral and bacterial distribution and disease by natural antibodies. Science 286, 2156–2159 10.1126/science.286.5447.2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Origgi F. C. (2007). Reptile immunology. Infectious Diseases And Pathology Of Reptiles (ed. Jacobson E R.), pp. 381–394 New York: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Packard G. C., Boardman T. J. (1999). The use of percentages and size-specific indices to normalize physiological data for variation in body size: wasted time, wasted effort? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 122, 37–44 10.1016/S1095-6433(98)10170-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier H. K., Lammers A., Hoekman J. J., De Vries Reilingh G., Zaanen I. T. A., Savelkoul H. F. K. (2004). Different levels of natural antibodies in chickens divergently selected for specific antibody responses. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 28, 39–49 10.1016/S0145-305X(03)00087-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier H. K., De Vries Reilingh G., Lammers A. (2008). Decreased specific antibody responses to α-Gal-conjugated antigen in animals with preexisting high levels of natural antibodies binding α-Gal residues. Poult. Sci. 87, 918–926 10.3382/ps.2007-00487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parslow T. G. (2001). Immunogens, antigens, and vaccines. Medical Immunology, 10th edition (ed. Parslow T G, Stites D P, Terr A I, Imboden J B.), pp. 72–81 New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division. [Google Scholar]

- Salvante K. G. (2006). Techniques for studying integrated immune function in birds. Auk 123, 575–586 10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[575:TFSIIF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandmeier F. C., Tracy C. R., DuPré S., Hunter K. (2009). Upper respiratory tract disease (URTD) as a threat to desert tortoise populations: a reevaluation. Biol. Conserv. 142, 1255–1268 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher I. M., Brown M. B., Jacobson E. R., Collins B. R., Klein P. A. (1993). Detection of antibodies to a pathogenic mycoplasma in desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii) with upper respiratory tract disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31, 1454–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinyakov M. S., Avtalion R. R. (2009). Vaccines and natural antibodies: a link to be considered. Vaccine 27, 1985–1986 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinyakov M. S., Dror M., Zhevelev H. M., Margel S., Avtalion R. R. (2002). Natural antibodies and their significance in active immunization and protection against a defined pathogen in fish. Vaccine 20, 3668–3674 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00379-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinyakov M. S., Dror M., Lublin–Tennenbaum T., Salzberg S., Margel S., Avtalion R. R. (2006). Nano- and microparticles as adjuvants in vaccine design: success and failure is related to host natural antibodies. Vaccine 24, 6534–6541 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifka M. K., Ahmed R. (1996). Long-term humoral immunity against viruses: revisiting the issue of plasma cell longevity. Trends Microbiol. 4, 394–400 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10059-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifka M. K., Matloubian M., Ahmed R. (1995). Bone marrow is a major site of long-term antibody production after acute viral infection. J. Virol. 69, 1895–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szu S. C., Clarke S., Robbins J. B. (1983). Protection against pneumococcal infection in mice conferred by phosphocholine-binding antibodies: specificity of the phosphocholine binding and relation to several types. Infect. Immun. 39, 993–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujvari B., Madsen T. (2011). Do natural antibodies compensate for humoral immunosenescence in tropical pythons? Funct. Ecol. 25, 813–817 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2011.01860.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman L. M., Vogel L. A., Bowden R. M. (2010). Understanding the vertebrate immune system: insights from the reptilian perspective. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 661–671 10.1242/jeb.038315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]