Summary

Endogenous 24-hour rhythms are generated by circadian clocks located in most tissues. The molecular clock mechanism is based on feedback loops involving clock genes and their protein products. Post-translational modifications, including ubiquitination, are important for regulating the clock feedback mechanism. Previous work has focused on the role of ubiquitin ligases in the clock mechanism. Here we show a role for the rhythmically-expressed deubiquitinating enzyme ubiquitin specific peptidase 2 (USP2) in clock function. Mice with a deletion of the Usp2 gene (Usp2 KO) display a longer free-running period of locomotor activity rhythms and altered responses of the clock to light. This was associated with altered expression of clock genes in synchronized Usp2 KO mouse embryonic fibroblasts and increased levels of clock protein PERIOD1 (PER1). USP2 can be coimmunoprecipitated with several clock proteins but directly interacts specifically with PER1 and deubiquitinates it. Interestingly, this deubiquitination does not alter PER1 stability. Taken together, our results identify USP2 as a new core component of the clock machinery and demonstrate a role for deubiquitination in the regulation of the circadian clock, both at the level of the core pacemaker and its response to external cues.

Key words: Circadian clock, Locomotor activity rhythms, PER1, Ubiquitin, USP2

Introduction

Daily oscillations exist for most behavioral and physiological functions of mammals, reflecting a need to coordinate these functions with recurrent changes in the environment. Such rhythms are generated and maintained by endogenous circadian clocks (Dunlap et al., 2004). The central clock in mammals, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, coordinates with varying degrees of control the clocks found in other brain regions and most peripheral tissues (Cuninkova and Brown, 2008; Okamura, 2007). Two major features characterize clock function: the self-sustainability of the system as revealed by persistent circadian rhythm generation in the absence of environmental cues, and its capacity to respond to cues (such as light, temperature, feeding), which enables synchrony with environmental cycles (Dunlap et al., 2004).

The molecular mechanism underlying these 24 h rhythms is based on transcriptional/translational feedback loops involving clock genes and proteins, and post-translational modifications of the clock proteins (Duguay and Cermakian, 2009; Reppert and Weaver, 2002). Essentially, BMAL1 and CLOCK proteins form a heterodimer that activates the transcription of genes including the Period (Per) 1 and 2 and Cryptochrome (Cry) 1 and 2 genes. The PER and CRY proteins accumulate in the cytoplasm where they are subject to post-translational modifications and subsequently enter the nucleus to repress the activity of CLOCK/BMAL1. Other regulatory loops exist, such as the ones formed by retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor (ROR) and REV-ERB factors that activate and repress Bmal1 transcription, respectively. The net effect of these loops is a rhythmic change in the activity of CLOCK/BMAL1, which serves as a basis for the rhythmic expression of thousands of genes in various tissues and cell types, participating in numerous biological processes, such as cell cycle regulation and metabolism (Sahar and Sassone-Corsi, 2009).

Clock proteins have short half-lives, a feature essential for their daily oscillations in abundance and activity. The ubiquitin-proteasome system appears to play an important role in mediating the rapid turnover of these proteins (Eide et al., 2005). In this pathway, ubiquitin becomes conjugated to target proteins through the sequential action of three types of enzymes – ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin protein ligases (E3) (Glickman and Ciechanover, 2002; Kerscher et al., 2006; Pickart, 2001). E3s number in hundreds and play the critical role of recognizing the substrate for ubiquitination. Formation of polyubiquitin chains on substrates, particularly chains where the C-terminus of the distal ubiquitin moiety is linked to lysine 48 of the more proximal ubiquitin moiety, targets the substrate for recognition and degradation by the proteasome. Mammalian E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes have been shown to specifically regulate the stabilities of PER and CRY proteins. Depletion or mutation of the E3 substrate receptors β-TRCP1/2 results in stabilization of PER proteins and altered circadian rhythms in cultured cells (Grima et al., 2002; Maier et al., 2009; Ohsaki et al., 2008; Reischl et al., 2007; Shirogane et al., 2005). Similarly, loss-of-function mutations in mice of another E3 substrate binding protein, FBXL3, result in stabilization of CRY proteins and lengthening of the free-running period (Busino et al., 2007; Godinho et al., 2007; Siepka et al., 2007), and recent data suggest that other ubiquitin ligases are probably involved in CRY regulation (Dardente et al., 2008; Kurabayashi et al., 2010). E3 ligases involved in REV-ERBα degradation have also recently been identified (Yin et al., 2010).

Similar to other covalent modifications such as protein phosphorylation and methylation, protein ubiquitination is reversible. Deubiquitination is mediated by approximately one hundred deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), belonging to five families (Komander et al., 2009; Sowa et al., 2009). DUBs can remove ubiquitin from target proteins and thereby reverse the effects of ubiquitination. Thus, it is quite conceivable that DUBs could regulate clock proteins through removal of degradation signals attached by β-TRCP1/2, FBXL3 and other ligases. We previously cloned and characterized the DUB ubiquitin specific peptidase 2 (USP2) from rat testis (formerly, UBP-testis) (Lin et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2001). Examination of circadian microarray data reveals that the gene encoding USP2 has a highly rhythmic circadian expression pattern in multiple tissues (Kita et al., 2002; McCarthy et al., 2007; Oishi et al., 2005; Storch et al., 2002; Storch et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2008). This feature is shared with a very limited number of genes, including core clock components (Duffield, 2003; Yan et al., 2008). Furthermore, recombinant ubiquitin specific protease 41 (UBP41, a truncated isoform of USP2) can, in vitro, remove ubiquitin attached to BMAL1 (Lee et al., 2008) and more recently, overexpression of USP2 was observed to stabilize BMAL1 (Scoma et al., 2011). Therefore, we employed gene targeting and cellular studies to define more precisely the in vivo role of USP2 in circadian behavior and light response and its impact on the ubiquitination and regulation of clock proteins. We show that USP2 acts as an integral component of the circadian clock through deubiquitination of PER1, and that Usp2 gene deletion in mice leads to altered circadian behavior and expression of core clock components.

Results

Generation of Usp2 knock-out (KO) mice

The Usp2 gene encodes two isoforms, USP2a and USP2b, 69 kDa and 45 kDa respectively, which share a common core catalytic domain, but have distinct N-termini due to use of alternative promoters. Mice lacking functional USP2 were generated by gene targeting as previously described (Bédard et al., 2011). These mice lack exons 4–6 of Usp2 gene (Ensembl Gene identifier ENSMUSG00000032010), which encode part of the common catalytic domain, including the active site cysteine residue essential for deubiquitination. Following backcrossing for at least 5 generations, heterozygous mice were then bred to generate homozygous Usp2 KO mice and wild-type (WT) littermates, all of them being viable with no apparent disturbances, except that Usp2 KO males were severely subfertile (Bédard et al., 2011).

Altered behavioral rhythms in Usp2 KO mice

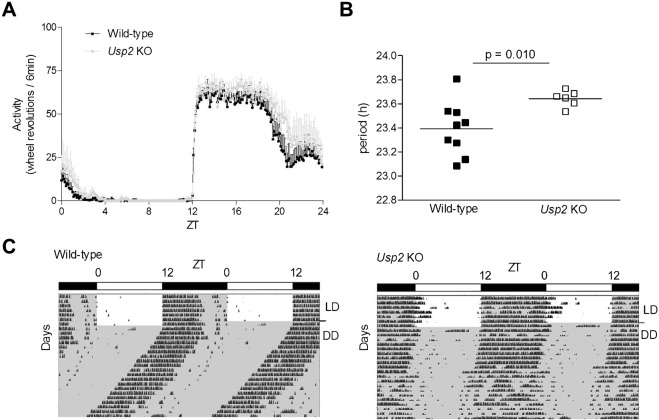

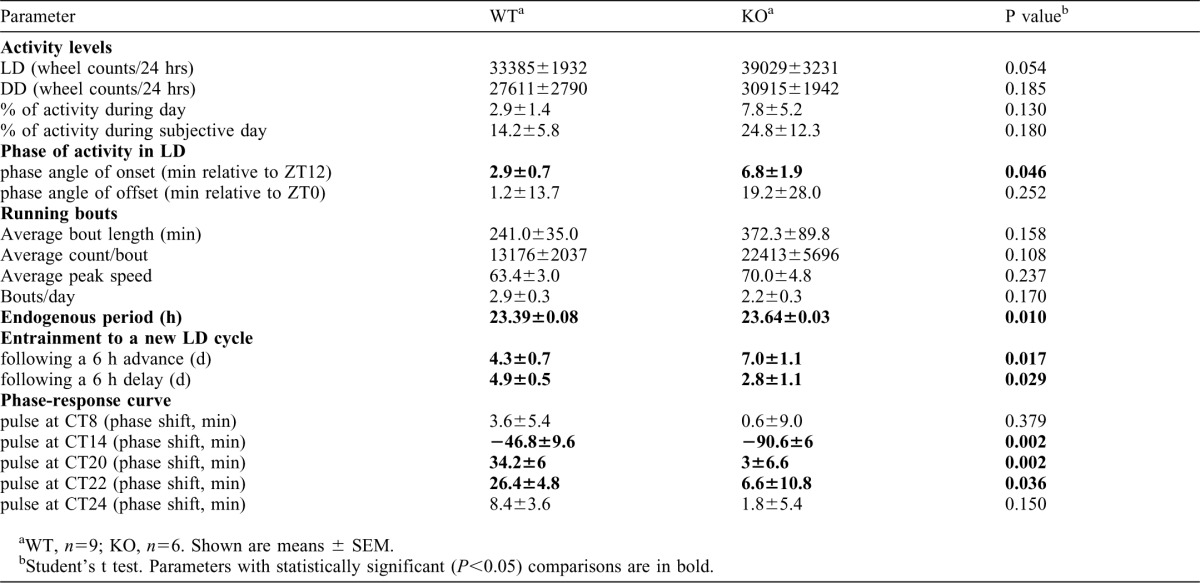

The role of USP2 in the circadian system was first assessed by studying locomotor activity rhythms of Usp2 WT and KO mice in running wheel cages. Mice were first exposed to a 12 h light:12 h dark (LD) cycle followed by constant darkness (DD). Under LD conditions, levels of total daily locomotor activity, percentage of activity recorded during daytime and phase angle of activity offset were not significantly different between genotypes, although mean values of all parameters were slightly increased in Usp2 KO mice (Fig. 1A; Table 1). Under LD cycle conditions, Usp2 KO mice started running significantly later than WT littermates relative to lights off, i.e. the phase angle of activity onset was altered. In DD, Usp2 KO mice retained rhythmicity, normal overall activity levels and percentage of activity during the subjective day (Table 1). However, the free-running period (τ), a key intrinsic characteristic of the central circadian clock, was significantly increased in Usp2 KO mice (Fig. 1B,C; Table 1) (also reproduced in an additional group of mice, data not shown), suggesting the involvement of USP2 in the molecular clockwork.

Fig. 1. Disruption of Usp2 increases mouse free-running period.

(A) Wild-type and Usp2 KO mice were entrained under a 12:12 LD (12 h light, 12 h dark) cycle and their locomotor activity was recorded over 10 d. The average amounts of wheel revolutions over 24 h (Zeitgeber time, ZT0 is the time of lights on) during these 10 d were calculated in 6 min time bins for both genotypes. WT, n = 9; KO, n = 6. (B) Wild-type and Usp2 KO mice were transferred to constant darkness (DD) and locomotor activity recordings from days 3 to 14 in free running conditions were used to assess their internal period length with the Chi2 periodogram analysis. (C) Representative actograms of wild-type and Usp2 KO mice entrained under a 12:12 LD cycle followed by DD. The bar above each actogram represents the lighting regimen in LD (white boxes indicate presence of light, dark boxes indicate nighttime). Transition to DD is indicated by the line on the right of the actograms.

Table 1. Running wheel activity characterization of Usp2 KO mice.

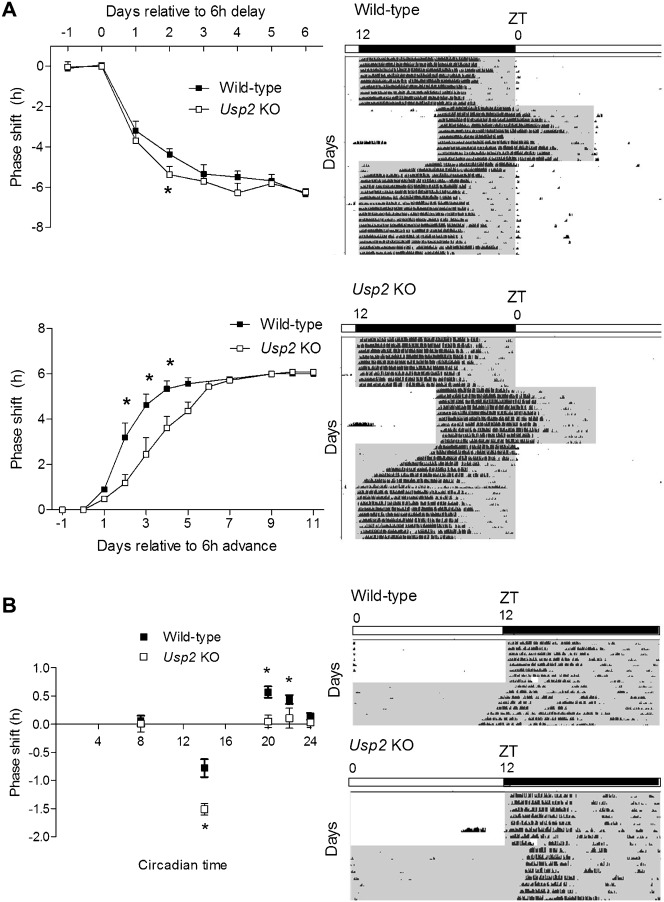

To test whether USP2 is also involved in entrainment of the clock to external cues, we assessed its response to light in Usp2 KO and WT mice. Usp2 KO mice entrained more slowly than WT littermates to a 6 h advance of the LD cycle (i.e. the lights off and lights on occur 6 h earlier in the new LD cycle, mimicking eastward travel; KO, 7.0±1.1 d; WT, 4.3±0.7 d; p = 0.017) (Fig. 2A, lower left panel, and bottom of the actograms), while the same mice showed faster entrainment to a 6 h delay (i.e. the lights off and lights on occur 6 h later in the new LD cycle, mimicking westward travel; KO, 2.8±1.1days; WT, 4.9±0.5 days; p = 0.029) (Fig. 2A, upper left panel, and top of the actograms). Interestingly, when we assessed the responses of Usp2 KO mice to short light pulses across the daily cycle, we observed alterations that were consistent with their behavioral responses to shifts of the LD cycle (Fig. 2B). Indeed, Usp2 KO mice had a significantly increased response to a light pulse in the early night producing a phase delay (Circadian time, CT14), but significantly reduced responses to phase-advancing light pulses in the later part of the night (CT20–24). Similar observations in these parameters were made with another set of animals with a purer genetic background (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that USP2 is required for adequate responses of the clock to photic cues as well as setting clock speed.

Fig. 2. Disruption of Usp2 alters both the entrainment properties of mice and their responses to light pulses.

(A) Entrainment following shifts in the light:dark cycle. Wild-type and Usp2 KO mice were first entrained to a 12:12 LD cycle for 10 d prior to being exposed to a 6 h delay of the LD schedule. Animals were then left to re-entrain to the new schedule. The numbers of days required for entrainment and the phase shift observed every day were evaluated (using the offsets of activity as a marker of phase, because the onsets of activity are likely masked by light). Once fully entrained for several days, animals were exposed to a 6 h phase advance and the same parameters were measured (using the onsets of activity as a marker of phase). Representative actograms for both genotypes are shown on the right. White indicates presence of light, and grey/black indicates lights off. *: P<0.05 (2-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc analysis). (B) Phase-response curves of response to light of wild-type and Usp2 KO mice. For each light pulse administered at different circadian times (CT8, CT14, CT20, CT22, and CT24), animals were entrained to a LD 12:12 cycle for 2 weeks before being released in constant darkness for 10 d. The pulse (∼ 200 lux) was administered on the first night after the end of LD or on the first subjective day in DD, and phase shifts were calculated. Representative actograms for both genotypes exposed to a light pulse at CT14 are shown on the right. *: P<0.05 (t-test between genotypes for each time point).

Altered gene expression rhythms in Usp2 KO mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)

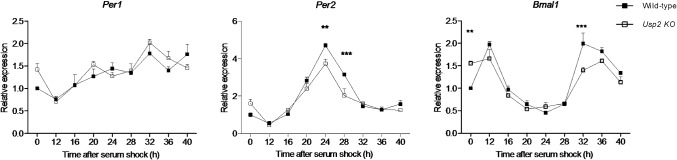

To test if the abnormal circadian behavior found in Usp2 KO mice is associated with changes in the molecular clockwork, we studied clock gene RNA expression in Usp2 KO and WT MEFs synchronized with a serum shock, a typical method used to assess molecular clock function in cultured cells. Rhythmic expression of Per1, Per2 and Bmal1 mRNA was observed in both the WT and KO cells. However, peak Per2 and Bmal1 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in Usp2 KO MEFs (Fig. 3, middle and right panels), while Per1 mRNA levels were not significantly different between genotypes (Fig. 3, left panel).

Fig. 3. Disruption of Usp2 alters the circadian expression of clock genes.

Wild-type and Usp2 KO MEFs were grown to confluence and synchronized with a serum shock. Cells were serum-starved overnight and exposed to 50% horse serum for 2 h, followed by serum-free medium. At the indicated times, cells were processed for RNA extraction and RNA was used in reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR for clock genes Per1, Per2 and Bmal1. Relative expression was normalized to β-actin and calibrated to a time 0 WT sample. n = 4 per time point. Two-way ANOVAs: Per1: time P<0.0001, genotype p = 0.145, interaction p = 0.1454; Per2: time P<0.0001, genotype p = 0.0121, interaction p = 0.0003; Bmal1, time P<0.0001, genotype p = 0.0279, interaction P<0.0001. Post-hoc tests (Bonferroni post-tests): **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. The experiment was done twice, with similar results.

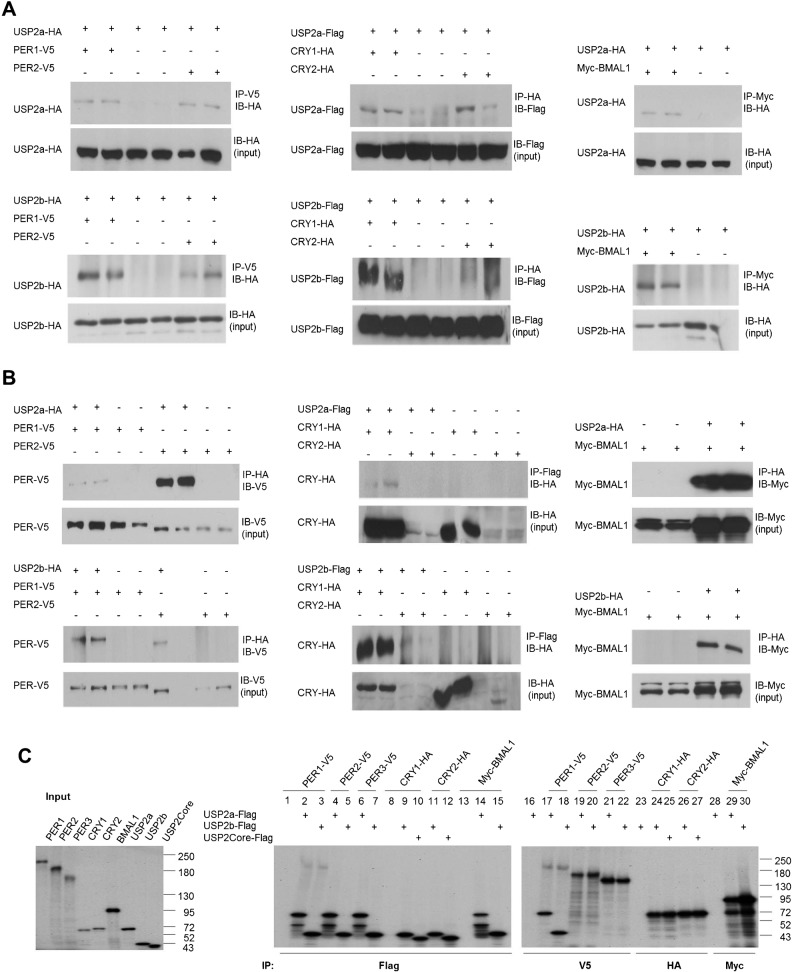

USP2 interacts directly with PER1

The running wheel data and the expression of clock components in MEFs together indicate a role for USP2 in the molecular clockwork. Therefore, we next attempted to define how USP2 could affect the function of clock components. First, we asked whether USP2 could interact with clock proteins. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments performed on transfected cells revealed association of both USP2a and USP2b with PER1, PER2, CRY1, CRY2 and BMAL1 (Fig. 4A,B). Another deubiquitinating enzyme, USP3, did not interact with PER1 (data not shown). Clock proteins are often found in multi-protein complexes (Lee et al., 2001). To test if these interactions were direct, each of the clock proteins was expressed by in vitro translation and incubated with USP2a, USP2b, or USP2 core region. Reciprocal immunoprecipitation of USP2a or USP2b and clock proteins resulted in co-precipitation of USP2a and USP2b with PER1 but none of the other clock proteins (Fig. 4C). Further co-IP experiments found that the common catalytic core region was sufficient for the interaction (data not shown). These findings show that USP2 binds PER1 directly and indicate that the interaction of USP2 with the other clock proteins is indirect and possibly occurring within a complex that contains components known to participate in the main negative feedback loop of the circadian clock, including PER1.

Fig. 4. USP2 interacts directly with PER1 and co-immunoprecipitates with other clock proteins.

(A) HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing PER-V5, CRY-HA or Myc-BMAL1, HA- or Flag-tagged USP2 isoforms, or the corresponding empty vector. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) of the clock protein using anti-tag antibodies, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies to detect the USP2 isoform. Equal transfection of HA- or Flag-tagged USP2 was verified by IB on cell lysates (input). Each experiment was performed in duplicate and repeated twice, with similar results. (B) Reciprocal co-IPs were performed on same set of whole-cell lysates as in (A), using an antibody to precipitate the USP2 isoform followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies against the clock protein. The experiment was performed in duplicate and repeated twice, with similar results. (C) USP2 directly interacts with PER1 in vitro. Clock proteins PER1-3, CRY1-2, BMAL1, and USP2a, 2b and core region were translated in vitro in the presence of 35S-methionine using a reticulocyte lysate system (input). Reciprocal IPs were performed on mixtures of the in vitro translated USP2 and individual clock proteins. USP2 core region was used in IP of CRYs instead of USP2a because USP2a migrates very close to CRYs in SDS-PAGE. The immune complexes were separated by 5–10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed after autoradiography. The experiment was done two or three times with similar results for each pair of proteins.

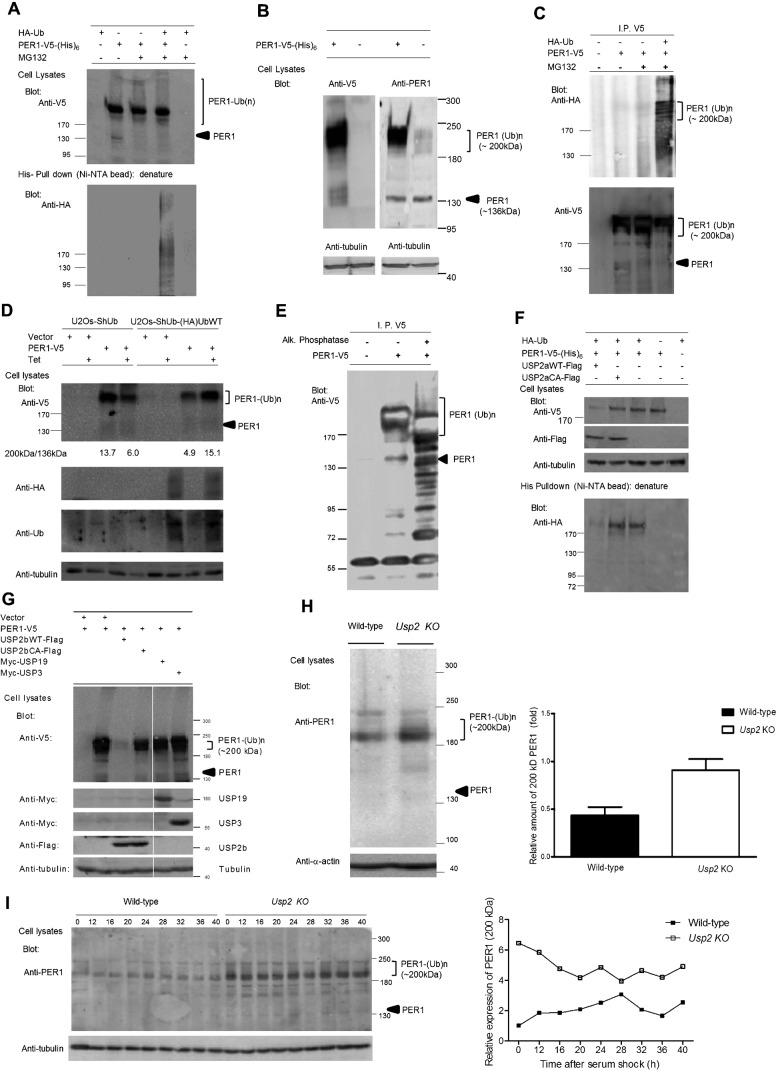

PER1 is ubiquitinated in cells and is a physiological substrate of USP2

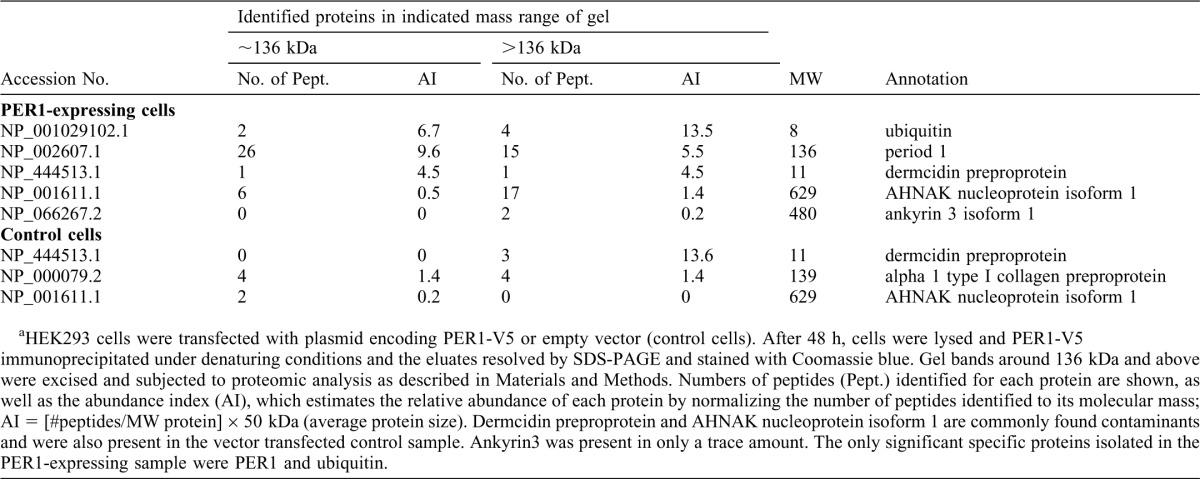

Previous studies have shown that PER1 can be ubiquitinated (Shirogane et al., 2005). We therefore decided to confirm this finding and determine whether USP2 can modulate this ubiquitination. When His-tagged PER1 was expressed in HEK293 cells, immunoblotting of the cell lysate revealed two isoforms of PER1 (Fig. 5A, second lane). The faster migrating isoform corresponded in size to the predicted 136 kDa molecular weight of PER1. However, surprisingly, most of the immunoreactivity migrated as a broad band of approximately 200 kDa (Fig. 5A, lanes 2–4). These bands were observed with antibodies directed against the epitope tag as well as with anti-PER1 antibodies (Fig. 5B) confirming the identity of these bands. In addition, fainter bands of similar size were observed in cells transfected with empty vector, when using the anti-PER1 antibody but not the anti-V5 tag antibody, showing that endogenous PER1 also exists as similar isoforms. To determine whether the larger ∼200 kDa isoform may represent ubiquitinated PER1, the cells were transfected with plasmids expressing both His-tagged PER1 and HA-ubiquitin. The PER1 was affinity isolated with Ni-NTA beads under denaturing conditions and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibodies (Fig. 5A). A strong signal in the ∼200 kDa region confirmed that PER1 is ubiquitinated. Using less concentrated SDS-PAGE to better resolve this high MW region, multiple immunoreactive bands were visible, consistent with ubiquitination of the protein (Fig. 5C). We confirmed this with additional studies using distinct approaches. First, we transfected the PER1 plasmid in a U2Os cell line that can express shRNAs against ubiquitin genes upon exposure to tetracycline (Xu, M. et al., 2009). Upon tetracycline treatment, ubiquitin levels fell as expected and this was associated with a decrease in the level of the 200 kDa PER1 form. Furthermore, re-expressing ubiquitin in these cells increased the levels of this form, arguing that this band indeed represents ubiquitinated PER1 (Fig. 5D). PER1 is also known to be phosphorylated (Akashi et al., 2002; Takano et al., 2004). To confirm that this slower-migrating PER1 is not solely due to phosphorylation, we isolated PER1 from cell lysates by IP and treated it with alkaline phosphatase. This treatment resulted in a decrease in the size of slow-migrating PER1, which nevertheless remains larger than 136 kDa with discrete bands visible (Fig. 5E). Finally, PER1 was isolated under denaturing conditions and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The band at ∼136 kDa and the gel region above were excised separately and subjected to trypsin digestion followed by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometric analysis of the peptides (Table 2). The analysis demonstrated that PER1 and ubiquitin were the most abundant proteins in the samples and were absent in control samples prepared from vector-transfected cells. Peptides identified for the ∼136 kDa form originated from most of the PER1 protein except for the extreme amino and carboxy terminal ends. In addition, the V5 tag used to isolate PER1 for mass spectrometry analysis was located at the C-terminal end. The only region not positively identified in the ∼136 kDa form of PER1 was the first 68 amino acids, making it very unlikely that this form arises simply as a degradation product of the ∼200 kDa form (data not shown). As expected, more ubiquitin was present in the high molecular weight region above the 136 kDa area where ubiquitinated PER1 had been detected by immunoblotting (Table 2). This confirmed the purity of the affinity isolation of PER1 as well as its ubiquitination.

Fig. 5. PER1 is ubiquitinated in cells and is a substrate of USP2.

(A) PER1 is ubiquitinated in cells. PER1-V5(His)6 was co-expressed with HA-Ub in HEK293 cells. Cells were treated without or with proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 6 h to accumulate ubiquitin-conjugated proteins and then lysed under denaturing conditions. His-tagged PER1 was affinity-isolated with Ni-NTA agarose beads and blotted with anti-HA antibody to detect ubiquitinated PER1 (lower panel). A broad band of approximately 200 kDa was found to be the major form of PER1. This experiment was done twice, with similar results. (B) PER1 is expressed in cells as two major isoforms, of ∼136 kDa and ∼200 kDa. HEK293 cells were transfected with empty plasmid or plasmid expressing V5-tagged PER1. Lysates were then analyzed by immunoblotting with either anti-V5 or anti-PER1 antibody. (C) High molecular weight (MW) PER1 contains multiple bands. HEK293 cells were transfected and whole cell lysates were prepared as in (A), PER1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 antibody. The immune complexes were separated by 5% SDS-PAGE to resolve proteins in high molecular weight region, immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody to detect ubiquitinated PER1 (upper panel), and re-blotted with anti-V5 antibody (lower panel). Multiple ubiquitinated PER1 bands were found to migrate in the gel region around 200 kDa. (D) High MW PER1 is regulated by the abundance of ubiquitin in cultured cells. PER1-V5(His)6 was expressed in U2Os-shUb and U2Os-shUb-HAUbWT cells, which were treated with tetracycline to induce expression of the shUb to silence the endogenous ubiquitin genes in both cell lines and simultaneously induce the expression of HA-tagged ubiquitin in the U2Os-shUb-HAUbWT cell line. The ratio of the ubiquitinated to the non-ubiquitinated form of PER1 was determined. This experiment was done twice, with similar results. (E) PER1-V5 was expressed in HEK293 cells and the cells were treated with MG132 for 6 h prior to lysis in the absence of phosphatase inhibitors. PER1-V5 was immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 antibody, incubated with alkaline phosphatase, resolved on 5–10% SDS-PAGE, and blotted with anti-V5 antibody. (F,G) USP2, but not USP3 or USP19, regulates the ubiquitination of PER1 in HEK293 cells. (F) USP2a wild-type (USP2aWT) or inactive mutant (USP2aCA) was co-expressed with PER1-V5(His)6 and HA-Ub in HEK293 cells. PER1-V5(His)6 was isolated and analyzed as in panel (A). The ubiquitinated form of PER1 is decreased in the presence of USP2aWT. This experiment was done twice, with similar results. Note that the ∼200 kDa band is less broad than in other figures due to use of a minigel. (G) PER1-V5(His)6 was expressed in HEK293 cells alone or with HA-tagged USP2b, Myc-tagged USP19 or USP3. Cells were lysed and cellular proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (H,I) Levels of ubiquitinated PER1 accumulate in Usp2 KO embryonic fibroblasts. (H) Lysates from either WT or Usp2 KO MEFs (unsynchronized) were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-PER1 antibodies. The ubiquitinated PER1 protein levels were quantified and normalized to actin. Shown are a representative blot and the mean±SEM from three independent experiments. (I) Lysates were prepared from either WT or Usp2 KO MEFs at the indicated times following synchronization by a serum shock as in Fig. 3 and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-PER1 antibodies. The ubiquitinated PER1 protein levels were quantified, normalized to γ-tubulin and calibrated to the PER1 levels of WT MEF at time 0. The immunoblots from two series of culture wells processed in parallel gave similar results and one series is shown here. The experiment was done twice using two different sets of MEFs prepared from embryos in different backcross backgrounds and similar results were seen in the two separate experiments.

Table 2. Mass spectrometric analysis of PER1a.

We next tested whether USP2 could modulate the ubiquitination of PER1. A first indication of this was that the form of PER1 found to interact with USP2 in the co-IP assays (Fig. 4B) was the slower-migrating form. His-tagged PER1 and HA-tagged ubiquitin were expressed with or without co-expression of USP2a or a catalytically inactive (CA) mutant form (Fig. 5F). Overexpression of USP2a, but not the inactive CA mutant, resulted in lower levels of the ∼200 kDa ubiquitinated form of PER1. This reduction in the ∼200 kDa form in the presence of USP2 is not due to changes in Per1 mRNA levels, as confirmed by RT-PCR analysis (data not shown). Affinity isolation of the PER1 and blotting with anti-HA to detect ubiquitin confirmed again that this ∼200 kDa band was ubiquitinated PER1 and that the expression of USP2a decreased its level (Fig. 5F, compare lane 1 to lane 3). Expression of the USP2b isoform yielded a similar result (Fig. 5G) supporting the conclusion from our co-IP studies (Fig. 4) that recognition of PER1 by USP2 is not dependent on the distinct N-termini. Importantly, two other deubiquitinating enzymes USP19 and USP3, did not decrease levels of the ubiquitinated form of PER1 (Fig. 5G) indicating that this deubiquitinating activity was specific to USP2. Interestingly, this loss of the ∼200 kDa ubiquitinated form of PER1 did not lead to accumulation of the ∼136 kDa form, suggesting that USP2 mediated deubiquitination of PER1 may result in other modifications such as sumoylation or alternative ubiquitination that targets for degradation such as occurs with A20-mediated deubiquitination of the signaling protein RIP (Wertz et al., 2004).

To explore the effect of loss of USP2 on PER1 levels, we examined PER1 protein expression in lysates of unsynchronized MEFs from WT or Usp2 KO mice. Levels of the ∼200 kDa form of PER1 were indeed higher in the Usp2 KO samples and migrated as a broader, slower migrating band consistent with increased ubiquitination (Fig. 5H). These findings argue strongly for a physiological role of USP2 in the deubiquitination of PER1. When the clocks in the MEF cells were synchronized with a serum shock, the KO samples again demonstrated a higher level of PER1 protein, but in addition, the rhythmicity of PER1 expression appeared blunted (Fig. 5I). The increased levels of PER1 protein in the absence of an increase in Per1 mRNA levels (Fig. 3) is also consistent with this effect being due to a post-transcriptional mechanism such as decreased deubiquitination in the absence of USP2.

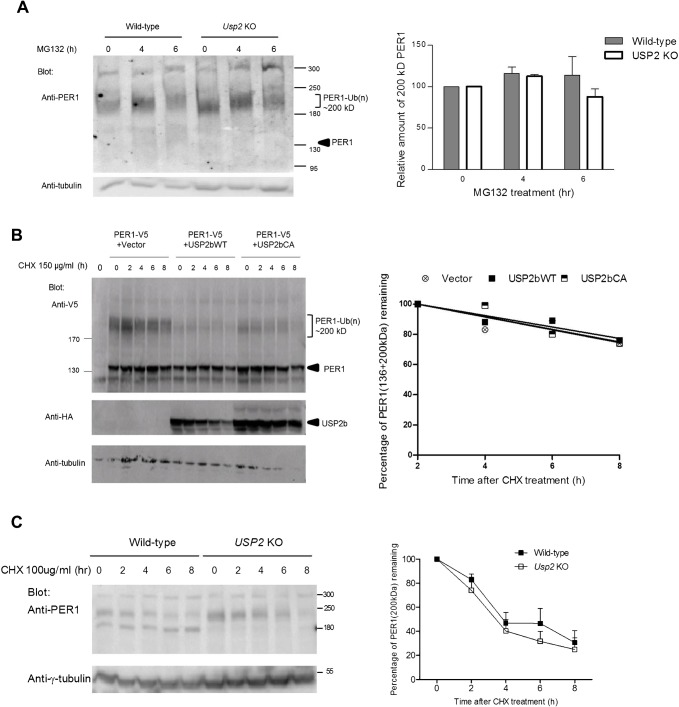

Deubiquitination of PER1 by USP2 does not stabilize it

The large amount of steady state ubiquitinated PER1 suggested that it was not being rapidly degraded. Indeed when Usp2 KO or WT MEFs were exposed to the proteasome inhibitor MG132 for up to 6 h prior to harvesting, the relative amounts of high molecular weight ubiquitinated PER1 did not increase significantly, suggesting that most of the ubiquitinated PER1 is not susceptible to rapid degradation by the proteasome (Fig. 6A). Supporting this, we observed that co-transfecting the HEK293 cells with USP2b or a catalytically inactive mutant isoform did not affect the rate of degradation of the PER1 protein, measured as the rate of disappearance of the protein following inhibition of protein synthesis with cycloheximide (Fig. 6B). This does not appear to be an artifact of overexpression, as loss of USP2 in the Usp2 KO MEF cells also had no effect on the stability of the endogenous PER1 protein (Fig. 6C). Thus, USP2 appears to regulate PER1 ubiquitination without significant effects on its overall stability.

Fig. 6. USP2 does not regulate the stability of PER1.

(A) Wild-type and Usp2 KO MEFs were treated with proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 µM) for the indicated times prior to lysis. Cellular proteins were resolved by 5–10% gradient SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-PER1 antibodies. The high MW ubiquitinated PER1 was quantified, normalized to tubulin and the sample without MG132 treatment was set at 100. Left: Representative immunoblot. Right: Quantification of ubiquitinated PER1 bands from three individual experiments. Shown are mean±SEM. (B) PER1-V5 was expressed alone or with wild-type USP2b or inactive USP2bCA mutant in HEK293 cells. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with cycloheximide (150 µg/mL) and lysed at the indicated times. Cellular proteins were separated by 5–10% gradient SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting (left). Total (136 and 200 kDa bands) PER1 was quantified and its disappearance over time plotted (right). Shown are the means from three independent experiments for each condition. In some studies, PER1 levels increased between the 0 and 2 h time points and therefore the rate of disappearance of PER1 is only shown starting at 2 h. (C) Wild-type and Usp2 KO MEFs were treated with cycloheximide (100 µg/mL) and processed as in (B). The high MW PER1 was quantified, normalized to tubulin and the samples at 0 h set at 100%. Shown are mean±SEM from three independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate a role for deubiquitination in regulation of the circadian clock in vivo. Mice with an inactivated Usp2 gene exhibited a longer free-running period of locomotor activity rhythms (Fig. 1), indicative of a role in defining the speed at which the clock runs. In addition, Usp2 KO mice demonstrated altered light-induced resetting of the clock (Fig. 2), indicating an involvement of USP2 in light-dependent signaling pathways in the SCN. Thus, the USP2 deubiquitinating enzyme modulates the two major features of clock function – its intrinsic circadian rhythm and its capacity to respond to external cues.

A recent report described the circadian characterization of Usp2 KO mice (Scoma et al., 2011). In contrast to our data, the authors found no difference in free-running period of wheel-running rhythms in KO mice compared to WT controls, and only a subtle phenotype in the response of the clock to light treatment (increased phase advances—like in our data—but only after a 4-hour dim light exposure at ZT12, but not later in the night or at higher light irradiances). The difference might be due to the KO strategy (our KO mice lack exons 4 to 6, while the mice described in the other report lack exons 3 and 4). Also, the mice described by Scoma et al. appear to retain low amounts of a shorter form of the USP2b isoform, where the first exon of Usp2b was alternatively spliced in frame to exon 5, which was deleted in our mice. In any case, our description of Usp2 KO mice is novel in that it presents alterations of free-running circadian behavior, of light-response by the clock in both the delaying and advancing parts of the phase response curve, and of clock gene expression in KO cells.

The ability of USP2 to modulate these central functions of the clock suggested that it acts on the molecular clock machinery. Indeed, we observed a reduced amplitude of Per2 and Bmal1 mRNA rhythms and constitutively elevated levels of PER1 protein in serum shock-synchronized Usp2-deficient MEFs, compared to WT cells (Fig. 3, Fig. 5H,I). These high levels of PER1 protein, and in particular of the 200 kDa ubiquitinated form, in KO fibroblasts, indicate a role for USP2 in post-translational regulation of clock proteins.

Accordingly, we found that USP2 was able to interact with core clock proteins – PER1, PER2, CRY1, CRY2, and BMAL1. However, in vitro assays indicated that USP2 could only interact directly with PER1, suggesting that USP2 interacts with the other clock proteins by virtue of their being in a complex with PER1 (Fig. 4). Expression of WT USP2, but not a mutant form or other deubiquitinating enzymes, leads to deubiquitination of PER1 (Fig. 5) and inactivating the Usp2 gene increased levels of the ∼200 kDa ubiquitinated PER1 (Fig. 5H,I), but surprisingly, USP2 did not alter the half-life of PER1 (Fig. 6). This suggests a model where ubiquitination of PER1 and its reversal by USP2-mediated deubiquitination modulate PER1 function rather than its stability. This would be in accordance with Yagita et al.'s model for PER2: they proposed that PER2 is ubiquitinated and then degraded in the cytoplasm, unless retained in the nucleus by a previously undefined mechanism involving CRY proteins (Yagita et al., 2002). In light of the shorter half-life of USP2 (compared to that of PER1) (Fig. 6B) and of its rhythmic expression peaking almost simultaneously with that of PER1 (Oishi et al., 2005; Oishi et al., 2003; Storch et al., 2002; Yan et al., 2008), the deubiquitination of PER1 by USP2 could be restricted to a specific circadian time and therefore be altering the function and/or localization of PER1 to fine tune the molecular clock in physiological conditions. A possible increase of repression by PER/CRY complexes due to constitutively high levels of PER1 (Fig. 5H,I) would be expected to lengthen the circadian cycle, consistent with the longer free-running period of Usp2 KO mice observed in our running-wheel experiments. Also, given the role of PER1 in light-induced phase resetting of the SCN clock, an interesting possibility is that USP2 may participate in phase resetting via its activity on PER1 ubiquination levels.

This non-degradative role of USP2 is somewhat surprising as PER proteins have previously been shown to be substrates of the ubiquitin ligases β-TRCP1/2 and this ubiquitination regulates stability of the PER proteins by targeting them for degradation by the 26S proteasome (Grima et al., 2002; Ohsaki et al., 2008; Reischl et al., 2007; Shirogane et al., 2005). It will be of interest to subsequently determine whether the types of ubiquitin chains found on PER1 are of types other than the classical chains linked via Lys48 residues that target proteins for recognition by the proteasome. It is possible that there is more than one pool of ubiquitinated PER1 with each pool containing distinct types of chain linkages and having a different susceptibility to degradation. The latter scenario has been observed with the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor 3, which is modified by either Lys48 or Lys63 chains, but only molecules modified with Lys48 chains are targeted for degradation (Sliter et al., 2011). In any event, it is clear that USP2 action on PER1 is not simply the reversal of that of the β-TRCP1/2 ligases.

Our work has also provided additional characterization of PER1 isoforms. Although most reports on PER1 have only described a single isoform, we were able, using gradient gel electrophoresis, to confirm the previous report of Akashi et al. describing two isoforms of PER1 (Akashi et al., 2002). In addition, we demonstrate clearly that the slower migrating isoform can arise as a result of ubiquitination and phosphorylation.

Although we have clearly delineated a role for USP2 in modulating the ubiquitination level of PER1, this does not exclude the possibility that USP2 is involved in modulating the clock through additional mechanisms. As we have shown, USP2 can interact indirectly with multiple clock proteins, so it remains possible that USP2 may modulate the ubiquitination and function of these other proteins. Indeed, in some of our studies, expression of USP2 isoforms increased steady state levels of BMAL1 (Fig. 4B, right panels). Accordingly, other investigators have shown that UBP41, a truncated form of USP2, can deubiquitinate BMAL1 in vitro (Lee et al., 2008), and that in the presence of USP2b, BMAL1 appears less ubiquitinated and more stable (Scoma et al., 2011). Such deubiquitination in vivo could lead to lower transactivation potential, as ubiquitination of BMAL1 is correlated with transcriptional activity (Lee et al., 2008), while the stabilization of this protein is correlated with transcriptional repression (Dardente et al., 2007).

Collectively, our studies show that the rhythmically-expressed deubiquitinating enzyme USP2 is an integral component of the clock machinery. By its action on the ubiquitination status of PER1, and possibly other clock proteins it interacts with, USP2 appears to exert a broad function, modulating both SCN central clock function (as seen by effects on both period length and response to photic stimuli) as well as peripheral clocks (as exemplified by our observations in embryonic fibroblasts).

Materials and Methods

Locomotor activity measurements of Usp2 KO mice

WT and Usp2 KO male mice were generated by breeding of heterozygous mice whose genetic backgrounds were 98.4% C57BL/6 (5 backcrosses with C57BL/6, starting from 50:50 C57BL/6:129Sv mice). At 2–3 months of age, the mice were housed in running wheel cages (Actimetrics, Wilmette, IL, USA) and entrained to a 12 h light (∼ 200 lux), 12 h dark (LD 12:12) cycle in a light-proof ventilated cabinet for 2 weeks prior to the start of experiments. Their running activity under the LD 12:12 cycle was recorded over the next 10 d. The following parameters were determined: activity onset and offset phase angle, daily overall activity and percentage of light phase activity. Animals were then transferred in constant darkness (DD) and recordings from days 3 to 14 in free-running conditions were used to define the internal period length, the circadian daily overall activity and the percentage of activity during subjective day. Next, entrainment properties to a jetlag simulation were determined in mice entrained to a LD 12:12 cycle for 10 d and then subjected to a 6 h delay (simulating westward flights) or a 6 h advance (simulating eastward flights). Phase resetting was characterized by the number of days required for full re-entrainment and by the shift (h) observed every day. Lastly, the phase-response curve for light-induced phase shifts was defined for WT and Usp2 KO mice, using an Aschoff type 2 procedure. Briefly, mice were entrained to a LD 12:12 cycle for 2 weeks before release in DD. On the first night after the end of LD or on the first subjective day in DD, a light pulse of 30 minutes was administered at CT8, 14, 20, 22, or 0/24, (circadian time (CT) 0 is the beginning of subjective day and CT12 is the beginning of the subjective night under DD) and the animal was then kept in DD for 10 days. Phase shifts are the difference, on the first day after the pulse, between regression lines fitted through activity onsets before and after the pulse. All data were analyzed using the Clocklab program (Actimetrics, Wilmette, IL, USA). Chi2 periodogram analysis was used for measurement of the free-running period. Procedures involving animals were carried out in accordance with guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Douglas Mental Health University Institute.

Reagents, plasmids and cDNA constructs

Cell culture media and Lipofectamine 2000 were from Invitrogen (Burlington, ON, Canada); proteasome inhibitor MG132 from Boston Biochem (Cambridge, MA, USA); N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), cycloheximide from Sigma (Markham, Ontario, Canada). Protease inhibitors (Mini Cocktail) were from Roche (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-PER1 (described previously) (Fahrenkrug et al., 2006), mouse anti-V5 [SV5-PK1], rabbit anti-V5, rabbit anti-Flag, rabbit anti-Myc (Abcam, Cambridge, MA,USA), mouse anti-Flag (M2), mouse anti-γ-tubulin, mouse anti-α-actin (Sigma), mouse anti-HA.11 (Covance, Montreal, QC, Canada), mouse anti-Myc (9E10) (Upstate, Lake Placid NY. USA), mouse anti-ubiquitin conjugates (FK2, International BioScience, Brighton, East Sussex, UK), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Protein A agarose and protein G plus agarose beads were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Plasmids expressing epitope tagged PERs (pCDNA3.1-mPER-V5-His6) and epitope tagged CRYs (pCDNA3.1-mCRY-HA) were kindly provided by Dr Steven M. Reppert (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA) and Dr Charles J. Weitz (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), respectively. Plasmid expressing Myc-tagged BMAL1 was described previously (Travnickova-Bendova et al., 2002). Plasmids expressing Myc-tagged USP3 (pcDNA3.1-myc-His-Usp3) was kindly provided by Dr. Elisabetta Citterio (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and plasmid expressing Myc-tagged USP19 was described previously (Lu et al., 2009). Oligonucleotides encoding Flag or HA tags were synthesized and subcloned into the EcoRI/BamHI sites or XhoI/HindIII sites of the pRK5 plasmids (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA). cDNAs encoding rat USP2a (AF202453), USP2b (AF202454) or their shared core region (Lin et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2001) were subcloned into the BamHI and XhoI sites of the modified pRK5 to generate the C-terminal Flag- or HA-tagged USP2a, 2b, and USP2 core proteins, respectively. The cysteine residue that is required for the catalytic activity of USP2 was mutated to alanine (rat USP2a C288A, and rat USP2b C67A) using the Quick-Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The HA-tagged ubiquitin expressing plasmid (HA-Ub/pRK5) was from Addgene.

MEFs, serum shock procedure, and quantitative PCR

Embryos derived from matings of heterozygous Usp2 male and female mice were harvested at 13.5 dpc to generate primary MEFs. MEFs were grown in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, GIBCO, Burlington, ON, Canada), 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, in 95% humidity and 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were then synchronized as described (Balsalobre et al., 1998), with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were plated in 6-well plates at 1 × 105 cells/well and grown to confluence. After an overnight serum starvation, cells were exposed to 50% horse serum for 2 h, followed by replacement with serum-free DMEM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. At indicated times, WT and Usp2 KO cells were processed as follows. For RNA analysis, cells from each well were lysed in 1 mL TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the RNA was isolated as per the manufacturer's protocol. For protein analysis, cells from each well were lysed in 10 mM Na phosphate pH 7.2, 1% Nonidet P40, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 200 µM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitor cocktail (CompleteTM Mini; Roche) for 30 min on ice, collected by scraping, centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min at 16,000 × g. The supernatants were kept at −80°C until analysis.

For reverse transcription, 2 µg RNA was transcribed to cDNA using a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative PCR was performed on the real-time cycler ABI Prism 7500 (Applied Biosystems) using Power SYBR Green Master Mix reagent (Applied Biosystems) and either 500 nM (Per1, Per2) or 100 nM (Bmal1, β-actin) of each primer (the sequences of which are: Per1: forward 5′-TTCAAGCTCTCAGGACTCTG-3′, reverse 5′-GGCAGTTTCCTATTGGTTGG-3′; Per2: forward 5′-CAGGAGAAGCTGAAGCTGC-3′, reverse 5′-GGACTGTCTTCCTCATATGG-3′; Bmal1: forward 5′-TGGAAGAAGTTGACTGCCTGGAAGG-3′, reverse 5′-GGCCCAAATTCCCACATCTGAAGTTAC-3′; β-actin: forward 5′-AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3′, reverse 5′-CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT-3′; primer efficiencies were verified using serial dilutions of cDNA) under the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Each PCR reaction was carried out in triplicate. Values were normalized to β-actin and calibrated to WT time 0 data using the ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Cell culture, transfections and immunoblotting

HEK293 and U2Os cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin in 5% CO2 at 37°C. DNA transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacturer's protocol. The indicated cDNA constructs in each experiment were adjusted with empty vectors to a total amount of 0.1 µg DNA/cm2 surface area of culture vessel. Lipofectamine 2000 was mixed with DNA in 3:1 (V:W) ratio and applied to 80–90% confluent cells at the time of transfection. After 48 h, cells were lysed, depending on the experiment, in either TTE (20 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM NaF, 5 mM Na pyrophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF), RIPA (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (V/V) NP-40, 0.5% (W/V) Na deoxycholate, 0.1% (W/V) SDS, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF), or TBS (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) lysis buffer containing 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide and protease inhibitor cocktail as previously described (Lu et al., 2009). Equal amounts of cellular proteins, determined with Micro BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL USA), were analyzed by immunoblotting.

For detection of ubiquitinated PER1, plasmids expressing PER1-V5(His)6 and HA-Ub were co-transfected into HEK293 cells. His-tagged PER1 was purified with Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) under denaturing conditions as described previously (Lu et al., 2009) and then analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA and anti-V5 tag antibodies.

To determine whether the in vivo abundance of ubiquitin regulates the ubiquitination status of PER1, plasmids expressing PER1-V5(His)6 were transfected into two U2Os stable cell lines, U2Os-shUb and U2Os-shUb-HAUbWT (gifts from Dr. Zhijian J. Chen, U. Texas, USA). Tetracycline was then added to the cells (1 µg/mL) to induce expression of the shUb to silence the endogenous ubiquitin genes in both cell lines and simultaneously induce the expression of HA-tagged ubiquitin in the U2Os-shUb-HAUbWT cell line (Xu, M. et al., 2009). The cells were lysed under denaturing conditions in TBS with 1% SDS. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting.

For immunoblotting, protein from cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated with the indicated primary antibodies then incubated with goat anti-mouse/rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to HRP, and finally with chemiluminescent substrate (ECL, Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA or Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and the signals detected with a cooled digital camera and quantified by Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Co-immunoprecipitations

For co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) from transfected cells, cell extracts containing 0.5–1 mg of cellular protein were preabsorbed with 50 µL of 50% protein G plus agarose beads for 1 h. The cell lysates were then incubated and rotated with 1–2 µg of anti-V5, anti-Flag (M2), anti-HA.11, anti-Myc and 30 µL of 50% protein G plus agarose beads for 4 h or overnight at 4°C. After five washes with 1 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer including two washes with high salt (0.5 M NaCl) lysis buffer, the beads were resuspended in Laemmli buffer, boiled and the supernatant processed for immunoblotting.

For co-IPs using in vitro translated proteins, plasmids encoding V5-tagged PER1, PER2 and PER3, HA-tagged CRY1 and CRY2, Myc-tagged BMAL1 and Flag-tagged USP2 isoforms were transcribed/translated in vitro using either TNT T7 or SP6 coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in the presence of 35S-methionine (Perkin Elmer), according to the manufacturer's instructions. To determine whether USP2 directly interacts with these clock proteins in vitro, reciprocal co-IP was performed on mixtures of translated USP2 and individual clock proteins. Five µL of the translated clock proteins and Flag-tagged USP2 isoform were mixed in 200 µL of TTE lysis buffer and immunoprecipitated with 1.5 µg anti-Flag (M2), anti-V5, anti-HA, or anti-Myc antibody. The immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed after autoradiography.

Alkaline phosphatase treatment

PER1-V5 was expressed in HEK293 cells and the cells were treated with MG132 for 6 h prior to lysis in TTE buffer containing 5 mM NEM and protease inhibitors but no phosphatase inhibitors. PER1-V5 was immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 antibody, incubated for 2 h at 37°C in 75 µL of 1× reaction buffer containing 10 U of alkaline phosphatase (Promega), resolved on 5–10% SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-V5 antibody.

Cycloheximide treatment

To determine whether USP2 regulates the stability of PER1, PER1-V5 was expressed alone or with USP2b WT or inactive USP2b CA mutant in HEK293 cells. After 24 h, the transfected cells were treated with cycloheximide (150 µg/mL) and lysed at the indicated times in TTE buffer containing 5 mM NEM and protease inhibitors. To determine whether USP2 regulates the stability of endogenous PER1, Usp2 KO and WT MEFs were treated with cycloheximide (100 µg/mL) and lysed as aforementioned. Cellular proteins were resolved by 5–10% gradient SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

Mass spectrometry analysis

HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmid encoding PER1-V5 or empty vector. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were lysed under denaturing condition in the presence of 1% SDS. PER1-V5 was immunoprecipitated from 120 mg of cellular protein with 30 µg of anti-V5 antibody and processed as previously described (Lu et al., 2009). The eluates from IP pellets were separated in a 5–10% gradient gel by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue G-250. The sample lanes both around and above 136 kDa were excised followed by in-gel trypsin digestion. The digested samples were analyzed by shotgun LC-MS/MS to identify proteins in these gel bands (Xu, P. et al., 2009). Proteins were identified by MS/MS spectra in a composite target/decoy database search (Elias and Gygi, 2007; Peng et al., 2003). Assigned peptides were filtered until all decoy matches were discarded.

Statistics

For wheel-running activity measurements, two-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc tests (Bonferroni post-tests) was used for comparison of kinetics of entrainment to advance and delays of LD cycle, and Student's t test was used for all other comparisons between genotypes. Chi-Squared Goodness-of Fit was used for the changes in PER1 ubiquitination in presence of MG132. Two-way ANOVAs followed by post-hoc tests (Bonferroni post-tests) were also used for analysis of QPCR on MEF RNA extracts. Differences were considered to be significant if P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of N.C.'s and S.S.W.'s laboratories for discussions, and K. Stojkovic for technical help. We are grateful to Dr. S.M. Reppert, Dr. C.J. Weitz, Dr. E. Citterio and Dr. Z.J. Chen for gift of reagents. This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (249731-2006 RGPIN, to N.C.) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP82734 and MOP115106, to S.S.W.). D.D. was supported by a fellowship from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ). N.C. was supported by an FRSQ salary award and a McGill Faculty of Medicine award.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Akashi M., Tsuchiya Y., Yoshino T., Nishida E. (2002). Control of intracellular dynamics of mammalian period proteins by casein kinase I ε (CKIε) and CKIδ in cultured cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1693–1703 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1693-1703.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsalobre A., Damiola F., Schibler U. (1998). A serum shock induces circadian gene expression in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell 93, 929–937 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81199-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bédard N., Yang Y., Gregory M., Cyr D. G., Suzuki J., Yu X., Chian R. C., Hermo L., O'Flaherty C., Smith C. E. et al. (2011). Mice lacking the USP2 deubiquitinating enzyme have severe male subfertility associated with defects in fertilization and sperm motility. Biol. Reprod. 85, 594–604 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busino L., Bassermann F., Maiolica A., Lee C., Nolan P. M., Godinho S. I., Draetta G. F., Pagano M. (2007). SCFFbxl3 controls the oscillation of the circadian clock by directing the degradation of cryptochrome proteins. Science 316, 900–904 10.1126/science.1141194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuninkova L., Brown S. A. (2008). Peripheral circadian oscillators: interesting mechanisms and powerful tools. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1129, 358–370 10.1196/annals.1417.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardente H., Fortier E. E., Martineau V., Cermakian N. (2007). Cryptochromes impair phosphorylation of transcriptional activators in the clock: a general mechanism for circadian repression. Biochem. J. 402, 525–536 10.1042/BJ20060827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardente H., Mendoza J., Fustin J. M., Challet E., Hazlerigg D. G. (2008). Implication of the F-Box Protein FBXL21 in circadian pacemaker function in mammals. PLoS ONE 3, e3530 10.1371/journal.pone.0003530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffield G. E. (2003). DNA microarray analyses of circadian timing: the genomic basis of biological time. J. Neuroendocrinol. 15, 991–1002 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguay D., Cermakian N. (2009). The crosstalk between physiology and circadian clock proteins. Chronobiol. Int. 26, 1479–1513 10.3109/07420520903497575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap J. C., Loros J. J., DeCoursey P. J. (2004). Chronobiology: Biological Timekeeping, p. 406.Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Eide E. J., Woolf M. F., Kang H., Woolf P., Hurst W., Camacho F., Vielhaber E. L., Giovanni A., Virshup D. M. (2005). Control of mammalian circadian rhythm by CKIepsilon-regulated proteasome-mediated PER2 degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 2795–2807 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2795-2807.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias J. E., Gygi S. P. (2007). Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4, 207–214 10.1038/nmeth1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrug J., Georg B., Hannibal J., Hindersson P., Gräs S. (2006). Diurnal rhythmicity of the clock genes Per1 and Per2 in the rat ovary. Endocrinology 147, 3769–3776 10.1210/en.2006-0305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman M. H., Ciechanover A. (2002). The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol. Rev. 82, 373–428 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godinho S. I., Maywood E. S., Shaw L., Tucci V., Barnard A. R., Busino L., Pagano M., Kendall R., Quwailid M. M., Romero M. R. et al. (2007). The after-hours mutant reveals a role for Fbxl3 in determining mammalian circadian period. Science 316, 897–900 10.1126/science.1141138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grima B., Lamouroux A., Chélot E., Papin C., Limbourg-Bouchon B., Rouyer F. (2002). The F-box protein slimb controls the levels of clock proteins period and timeless. Nature 420, 178–182 10.1038/nature01122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher O., Felberbaum R., Hochstrasser M. (2006). Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 159–180 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita Y., Shiozawa M., Jin W., Majewski R. R., Besharse J. C., Greene A. S., Jacob H. J. (2002). Implications of circadian gene expression in kidney, liver and the effects of fasting on pharmacogenomic studies. Pharmacogenetics 12, 55–65 10.1097/00008571-200201000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D., Clague M. J., Urbé S. (2009). Breaking the chains: structure and function of the deubiquitinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 550–563 10.1038/nrm2731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurabayashi N., Hirota T., Sakai M., Sanada K., Fukada Y. (2010). DYRK1A and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta, a dual-kinase mechanism directing proteasomal degradation of CRY2 for circadian timekeeping. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1757–1768 10.1128/MCB.01047-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Etchegaray J. P., Cagampang F. R., Loudon A. S., Reppert S. M. (2001). Posttranslational mechanisms regulate the mammalian circadian clock. Cell 107, 855–867 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00610-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Lee Y., Lee M. J., Park E., Kang S. H., Chung C. H., Lee K. H., Kim K. (2008). Dual modification of BMAL1 by SUMO2/3 and ubiquitin promotes circadian activation of the CLOCK/BMAL1 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 6056–6065 10.1128/MCB.00583-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Keriel A., Morales C. R., Bedard N., Zhao Q., Hingamp P., Lefrançois S., Combaret L., Wing S. S. (2000). Divergent N-terminal sequences target an inducible testis deubiquitinating enzyme to distinct subcellular structures. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 6568–6578 10.1128/MCB.20.17.6568-6578.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Yin L., Reid J., Wilkinson K. D., Wing S. S. (2001). Divergent N-terminal sequences of a deubiquitinating enzyme modulate substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20357–20363 10.1074/jbc.M008761200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Adegoke O. A., Nepveu A., Nakayama K. I., Bedard N., Cheng D., Peng J., Wing S. S. (2009). USP19 deubiquitinating enzyme supports cell proliferation by stabilizing KPC1, a ubiquitin ligase for p27Kip1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 547–558 10.1128/MCB.00329-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier B., Wendt S., Vanselow J. T., Wallach T., Reischl S., Oehmke S., Schlosser A., Kramer A. (2009). A large-scale functional RNAi screen reveals a role for CK2 in the mammalian circadian clock. Genes Dev. 23, 708–718 10.1101/gad.512209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J. J., Andrews J. L., McDearmon E. L., Campbell K. S., Barber B. K., Miller B. H., Walker J. R., Hogenesch J. B., Takahashi J. S., Esser K. A. (2007). Identification of the circadian transcriptome in adult mouse skeletal muscle. Physiol. Genomics 31, 86–95 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00066.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsaki K., Oishi K., Kozono Y., Nakayama K., Nakayama K. I., Ishida N. (2008). The role of beta-TrCP1 and beta-TrCP2 in circadian rhythm generation by mediating degradation of clock protein PER2. J. Biochem. 144, 609–618 10.1093/jb/mvn112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K., Miyazaki K., Kadota K., Kikuno R., Nagase T., Atsumi G., Ohkura N., Azama T., Mesaki M., Yukimasa S. et al. (2003). Genome-wide expression analysis of mouse liver reveals CLOCK-regulated circadian output genes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41519–41527 10.1074/jbc.M304564200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K., Amagai N., Shirai H., Kadota K., Ohkura N., Ishida N. (2005). Genome-wide expression analysis reveals 100 adrenal gland-dependent circadian genes in the mouse liver. DNA Res. 12, 191–202 10.1093/dnares/dsi003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H. (2007). Suprachiasmatic nucleus clock time in the mammalian circadian system. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 72, 551–556 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Schwartz D., Elias J. E., Thoreen C. C., Cheng D., Marsischky G., Roelofs J., Finley D., Gygi S. P. (2003). A proteomics approach to understanding protein ubiquitination. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 921–926 10.1038/nbt849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart C. M. (2001). Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 503–533 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reischl S., Vanselow K., Westermark P. O., Thierfelder N., Maier B., Herzel H., Kramer A. (2007). Beta-TrCP1-mediated degradation of PERIOD2 is essential for circadian dynamics. J. Biol. Rhythms 22, 375–386 10.1177/0748730407303926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert S. M., Weaver D. R. (2002). Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 418, 935–941 10.1038/nature00965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahar S., Sassone-Corsi P. (2009). Metabolism and cancer: the circadian clock connection. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 886–896 10.1038/nrc2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoma H. D., Humby M., Yadav G., Zhang Q., Fogerty J., Besharse J. C. (2011). The de-ubiquitinylating enzyme, USP2, is associated with the circadian clockwork and regulates its sensitivity to light. PLoS ONE 6, e25382 10.1371/journal.pone.0025382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirogane T., Jin J., Ang X. L., Harper J. W. (2005). SCFbeta-TRCP controls clock-dependent transcription via casein kinase 1-dependent degradation of the mammalian period-1 (Per1) protein. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26863–26872 10.1074/jbc.M502862200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siepka S. M., Yoo S. H., Park J., Song W., Kumar V., Hu Y., Lee C., Takahashi J. S. (2007). Circadian mutant Overtime reveals F-box protein FBXL3 regulation of cryptochrome and period gene expression. Cell 129, 1011–1023 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliter D. A., Aguiar M., Gygi S. P., Wojcikiewicz R. J. (2011). Activated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are modified by homogeneous Lys-48- and Lys-63-linked ubiquitin chains, but only Lys-48-linked chains are required for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1074–1082 10.1074/jbc.M110.188383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowa M. E., Bennett E. J., Gygi S. P., Harper J. W. (2009). Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell 138, 389–403 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch K. F., Lipan O., Leykin I., Viswanathan N., Davis F. C., Wong W. H., Weitz C. J. (2002). Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart. Nature 417, 78–83 10.1038/nature744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch K. F., Paz C., Signorovitch J., Raviola E., Pawlyk B., Li T., Weitz C. J. (2007). Intrinsic circadian clock of the mammalian retina: importance for retinal processing of visual information. Cell 130, 730–741 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano A., Isojima Y., Nagai K. (2004). Identification of mPer1 phosphorylation sites responsible for the nuclear entry. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32578–32585 10.1074/jbc.M403433200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travnickova-Bendova Z., Cermakian N., Reppert S. M., Sassone-Corsi P. (2002). Bimodal regulation of mPeriod promoters by CREB-dependent signaling and CLOCK/BMAL1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 7728–7733 10.1073/pnas.102075599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz I. E., O'Rourke K. M., Zhou H., Eby M., Aravind L., Seshagiri S., Wu P., Wiesmann C., Baker R., Boone D. L. et al. (2004). De-ubiquitination and ubiquitin ligase domains of A20 downregulate NF-kappaB signalling. Nature 430, 694–699 10.1038/nature02794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Skaug B., Zeng W., Chen Z. J. (2009). A ubiquitin replacement strategy in human cells reveals distinct mechanisms of IKK activation by TNFalpha and IL-1beta. Mol. Cell 36, 302–314 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P., Duong D. M., Seyfried N. T., Cheng D., Xie Y., Robert J., Rush J., Hochstrasser M., Finley D., Peng J. (2009). Quantitative proteomics reveals the function of unconventional ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation. Cell 137, 133–145 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagita K., Tamanini F., Yasuda M., Hoeijmakers J. H., van der Horst G. T., Okamura H. (2002). Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and mCRY-dependent inhibition of ubiquitylation of the mPER2 clock protein. EMBO J. 21, 1301–1314 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Wang H., Liu Y., Shao C. (2008). Analysis of gene regulatory networks in the mammalian circadian rhythm. PLOS Comput. Biol. 4, e1000193 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L., Joshi S., Wu N., Tong X., Lazar M. A. (2010). E3 ligases Arf-bp1 and Pam mediate lithium-stimulated degradation of the circadian heme receptor Rev-erb alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11614–11619 10.1073/pnas.1000438107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]