Abstract

Background

Cerebral hypoperfusion accompanies heart failure (HF) and is associated with reduced cognitive performance. Obesity is prevalent in persons with HF and is also a likely contributor to cognitive function, as it has been independently linked to cognitive impairment in healthy individuals. The current study examined the association between obesity and cognitive performance among older adults with HF and whether obesity interacts with cerebral hypoperfusion to exacerbate cognitive impairment.

Methods

Patients with HF (n = 99, 67.46 ± 11.36 years of age) completed neuropsychological testing and impedance cardiography. Cerebral blood flow velocity (CBF-V) measured by transcranial Doppler sonography quantified cerebral perfusion and body mass index (BMI) operationalized obesity.

Results

A hierarchical regression analysis showed that lower CBF-V was associated with reduced performance on tests of attention/executive function and memory. Elevated BMI was independently associated with reduced attention/executive function and language test performance. Notably, a significant interaction between CBF-V and BMI indicated that a combination of hypoperfusion and high BMI has an especially adverse influence on attention/executive function in HF patients.

Conclusions

The current findings suggest that cerebral hypoperfusion and obesity interact to impair cognitive performance in persons with HF. These results may have important clinical implications, as HF patients who are at high risk for cerebral hypoperfusion may benefit from weight reduction.

Key Words: Body mass index, Cerebral perfusion, Cognitive function, Heart failure, Obesity

Introduction

Nearly 6 million Americans currently have heart failure (HF) and an additional 660,000 new cases of HF are diagnosed each year [1]. HF is also the most common reason for recurrent hospitalizations [2] and carries elevated risk of morality [3], reduced functional independence [4], and poor quality of life [5]. HF also increases risk for cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease (AD), vascular dementia, and neuropathological insult [6,7,8]. Milder deficits in attention, executive function, memory, and language are also common and can be found in up to 75% of HF patients [9,10]. Although the mechanisms for cognitive impairment in HF are unclear, it is plausible that it stems from cerebral dysfunction predicated on deterioration of vascular health that causes cerebral hypoperfusion and subsequent ischemia [11]. Extant evidence also indicates that among HF patients, common vascular risk factors, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, depression, and obesity [12,13,14], may exacerbate cognitive dysfunction.

Indeed, obesity is one of the more common vascular risk factor for HF [14] and is found in >40% of HF patients [15]. Obesity in HF and cardiovascular disease populations is associated with numerous adverse outcomes, including increased mortality risk [16], reduced quality of life, poor emotional and physical well-being, and increased depressive symptomatology [17]. Moreover, obesity is also associated with increased risk of AD [18] as well as cognitive dysfunction and neuroimaging abnormalities independent of neurological and cardiovascular disease [19,20,21].

These findings suggest that obesity may exacerbate neuropathology and cognitive dysfunction in HF patients through additive independent influence or even through greater reductions in cerebral perfusion [22]. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to examine the independent effects of body mass index (BMI) on cognitive function among older adults with HF and to determine whether BMI interacts with cerebral perfusion to produce increased cognitive deficits in this population. We hypothesized that reductions in cerebral blood flow (CBF) would be associated with poorer cognitive function and such deficits would be exacerbated by elevated BMI.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 99 consecutive participants with HF who were enrolled in an ongoing study examining neurocognitive function among older adults with HF. Participants were recruited from primary cardiology practices at Summa Health System in Akron, Ohio, and reflect the HF population receiving treatment at that facility. The inclusion criteria were age of 50–85 years, English as a primary language, and a diagnosis of New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II or III at the time of enrollment. NYHA was confirmed by a medical record review. Potential participants were excluded for history of significant neurological disorder (e.g. dementia, stroke, multiple sclerosis, etc.), head injury with >10 min loss of consciousness, severe psychiatric disorder (e.g. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), past or current substance abuse/dependence, and renal failure. Participants averaged 67.46 ± 11.36 SD years of age, were 26.3% female, and 88.9% Caucasian. See table 1 for demographic and medical information.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 99 older adults with HF

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Patients, n | 99 |

| Age, years | 67.46 ± 11.37 |

| Female, % | 26.3 |

| Caucasian, % | 88.9 |

| Education, years | 13.44 ± 2.84 |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| BMI | 29.95 ± 7.23 |

| Cardiac index | 2.74 ± 1.03 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 115.88 ± 16.79 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 65.05 ± 9.73 |

| Diabetes, % | 32.3 |

| Myocardial infarction, % | 59.6 |

| Depression, % | 18.2 |

| Cerebral perfusion | |

| MCA, cm/s | 40.79 ± 11.33 |

| ACA, cm/s | 35.10 ± 10.86 |

| PCA, cm/s | 27.60 ± 8.12 |

| Global CBF-V, cm/s | 103.49 ± 25.73 |

Values are means ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

Measures

Neuropsychological Measures

A brief battery of neuropsychological tests was administered to assess cognitive function across multiple domains. All neuropsychological tests used in the current study exhibit strong psychometric properties, including excellent reliability and validity. The domains and neuropsychological tests administered are as follows:

Global cognitive function: Modified Mini Mental State Examination [23]

Attention/executive function: Trail Making Test B [24], Adaptive Rate Continuous Performance Test Hit Rate [25], Letter Number Sequencing [26], Stroop Color Word Interference Effect [27], Frontal Assessment Battery [28]

Memory: the California Verbal Learning Test-II short delay free recall, long delay free recall, and total hits [29]

Cerebral Blood Flow

We used transcranial Doppler ultrasonography under an expanded Stroke Prevention Trial in Sickle Cell Anemia (STOP) protocol [32] to assess CBF velocity (CBF-V) in the major brain arteries. The insonated arteries included the middle cerebral artery (MCA), the anterior cerebral artery (ACA), posterior cerebellar artery (PCA), intracranial vertebral arteries, basilar artery, terminal internal carotid artery, intracranial internal carotid artery, and ophthalmic artery. For each artery, the measurements provide several indices including mean flow velocity. As the index of global cerebral perfusion, we used the mean CBF-V in the ACA, MCA, and PCA. The CBF-V measures in each artery (i.e. ACA, MCA, and PCA) have high test-retest reliability (i.e. r = 0.90 to r = 0.95) [33].

HF Severity

Cardiac output from a seated resting baseline estimated preservation of cardiac function. Impedance cardiography signals were recorded via a Hutcheson Impedance Cardiograph (Model HIC-3000, Bio-Impedance Technology, Chapel Hill, N.C., USA) using a tetrapolar band-electrode configuration. The electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded from the Hutcheson Impedance Cardiograph using disposable ECG electrodes. The basal thoracic impedance (Zo), the first derivative of the pulsatile impedance (dZ/dt) and the ECG waveforms were processed using specialized ensemble-averaging software (COP, BIT Inc., Chapel Hill, N.C., USA), which was used to derive stroke volume using the Kubicek equation. Following instrumentation, Impedance cardiographic signals were recorded for seven 40-second periods during a 10-min resting baseline. Finally, all cardiac output measurements were divided by body surface area, yielding cardiac index (table 1).

Blood pressure (BP) was measured 7 times during the 10-min resting baseline using an automated oscillometric BP device (Accutor Plus Oscillometric BP Monitor, Datascope Corp., Mahwah, N.H., USA) providing systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressures. Initiating the BP reading triggered a concurrent 40-second impedance cardiography measure. The mean systolic and diastolic BP across the 7 trials served as the indices of systolic and diastolic BP.

Demographic and Medical History

Demographic and medical characteristics were collected through a review of participants’ medical charts and self-report. The summary of these characteristics is in table 1.

Procedures

The local Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures and all participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment. In addition to medical record review, participants completed demographic and medical history self-report measures. Height and weight were measured and used to calculate BMI. Individuals then completed impedance cardiography conducted by a trained research assistant to ascertain cardiac indices. Finally, a brief neuropsychological test battery assessed attention/executive function, memory, and language.

Statistical Analyses

To facilitate clinical interpretation and minimize discrepancy within scales, raw scores of the neuropsychological measures were transformed to T-scores (a distribution with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10) using normative data correcting for age. Memory scores were corrected for gender. Composite scores were computed for attention/executive function, memory, and language that consisted of the mean of the T-scores of neuropsychological measures within each cognitive domain.

Three separate multiple linear hierarchical regression models examined the interactive effect of BMI and CBF-V on each cognitive domain. All continuous predictors were transformed to Z-scores, gender was coded as 1 for males and 0 for females, and medical history was coded as 1 for a positive and 0 for a negative history. For all analyses, demographic and medical variables including age, gender, education, cardiac index, systolic and diastolic BP, and diagnostic history of diabetes, myocardial infarction, and depression were entered into the first block of the model. Medical history covariates were included in the model to account for the variance of common cardiovascular disease factors associated with obesity that influence cognitive function. BMI entered into the second block of the model and global CBF-V entered in the third block. Lastly, an interaction term consisting of the cross product of BMI and global CBF-V entered in the final block. Partial correlation analysis adjusting for medical and demographic characteristics was also conducted to clarify the association between BMI and global CBF-V.

Results

Cognitive Performance and Cerebral Perfusion

The Modified Mini Mental State Examination score was used to assess global cognitive status within the sample. Overall, the sample mean was 93.69 ± 4.59 SD, with 18.2% of the sample scoring <90, 40.4% between 90 and 95, and 41.4% >95 (table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of cognitive test performance (n = 99)

| Raw test performance | T-score | |

|---|---|---|

| Global cognitive function | ||

| 3MS | 93.69 ± 4.59 | – |

| Attention/executive function | ||

| ARCPT | 0.90 ± 0.06 | 53.43 ± 14.53 |

| LNS | 9.21 ± 2.69 | 52.24 ± 9.17 |

| TMTB, s | 116.66 ± 67.27 | 46.37 ± 15.41 |

| Stroop interference effect | 1.48 ± 6.93 | 51.42 ± 6.91 |

| Frontal Assessment Battery | 16.11 ± 2.16 | 44.83 ± 21.13 |

| Memory | ||

| CVLT SDFR | 7.42 ± 3.52 | 47.47 ± 10.48 |

| CVLT LDFR | 7.99 ± 3.69 | 47.58 ± 10.77 |

| CVLT recognition | 13.46 ± 2.40 | 45.00 ± 12.12 |

| Language | ||

| Boston Naming Test | 55.17 ± 3.93 | 52.92 ± 9.40 |

| Animal Fluency | 19.75 ± 5.01 | 55.38 ± 11.37 |

Values are means ± SD. 3MS = Modified Mini Mental State Examination; ARCPT = Adaptive Rate Continuous Performance Test hit rate; LNS = Letter Number Sequencing; TMTB = Trail Making Test B; CVLT = California Verbal Learning Test; SDFR = short delay free recall; LDFR = long delay free recall.

Lower global CBF-V was significantly associated with poorer attention/executive function (β = 0.28, p = 0.02) and memory (β = 0.26, p = 0.04), but not with language functioning (p = 0.85). See table 3 for a summary of hierarchical regression analyses for blocks 1–3.

Table 3.

A summary of hierarchical regressions examining predictors of cognitive function among older adults with HF (n = 99): blocks 1–3

| Variable | Attention/executive function, b (SE b) | Memory b (SE b) | Language b (SE b) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | |||

| Age | −2.05 (1.15) | −1.63 (1.13) | −0.15 (0.91) |

| Gender | −3.91 (2.53) | −3.21 (2.48) | −0.83 (2.01) |

| Education | 2.94 (1.08)** | 2.34 (1.06)* | 2.98 (0.85)** |

| Cardiac index | 0.55 (1.01) | −1.00 (0.99) | 0.05 (0.08) |

| Systolic BP | 0.02 (0.10) | 0.03 (0.10) | 0.06 (0.15) |

| Diastolic BP | −0.02 (0.19) | 0.00 (0.18) | −0.20 (0.15) |

| Diabetes | −1.97 (2.30) | 1.70 (2.25) | −0.32 (1.82) |

| MI | 0.89 (2.18) | −0.07 (2.13) | −2.22 (1.72) |

| Depression | −5.37 (2.91) | −0.39 (2.86) | −3.99 (2.31) |

| R2 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.22 |

| F | 1.68 | 1.04 | 2.54 |

| P | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.01 |

| Block 2 | |||

| BMI | −2.76 (1.18)* | −1.24 (1.19) | −2.24 (0.94)* |

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.27 |

| F for ΔR2 | 5.43 | 1.09 | 5.70 |

| P | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.02 |

| Block 3 | |||

| CBF-V | 2.82* | 2.55 (1.20)* | −0.18 (0.97) |

| R2 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.27 |

| F for ΔR2 | 5.72 | 4.55 | 0.04 |

| P | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.85 |

b = Unstandardized regression coefficients; SE = standard error; MI = myocardial infarction.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Body Mass Index

The HF patients had a mean BMI of 29.95 ± 7.23 SD. According to common categorization, 26.3% of the participants fell within the normal range (BMI 18.5–24.9), 36.4% were overweight (BMI 25–29.9), and 37.4% of the sample exhibited a BMI consistent with obesity (BMI ≥30). The BMI groups did not differ in age (F(2,98) = 0.38, p = 0.69), gender composition (χ2 (2, n = 99) = 5.24, p = 0.07), education (F(2,98) = 1.07, p = 0.35), systolic (F(2,98) = 0.51, p = 0.60) and diastolic (F(2,98) = 0.07, p = 0.93) BP, and frequency of myocardial infarctions (χ2 (2, n = 99) = 0.44, p = 0.80), diabetes (χ2 (2, n = 99) = 5.04, p = 0.08) or depression (χ2 (2, n = 99) = 0.57, p = 0.75). However, across groups, greater BMI was associated with lower cardiac index (F(2,98) = 12.99, p < 0.01). Of note, partial correlation adjusting for age, gender, education, systolic and diastolic BP, and history of diabetes, myocardial infarction, and depression showed that higher BMI was associated with lower mean velocity in the MCA (r(89) = −0.24, p = 0.04).

BMI Is Independently Associated with Cognitive Function

Elevated BMI was associated with reduced attention/executive (β = −0.28, p = 0.02) and language (β = −0.28, p = 0.02) scores after controlling for medical and demographic characteristics. There was no significant association between BMI and memory performance (β = −0.13, p = 0.30). Partial correlations adjusting for age, gender, education, cardiac index, systolic and diastolic BP, and diagnostic history of diabetes, myocardial infarction, and depression showed that higher BMI was associated with poorer performance on the Stroop Color Word Interference (r(88) = −0.25, p = 0.02), Trail Making Test B (r(88) = −0.28, p = 0.01), the Adaptive Rate Continuous Performance Test Hit Rate (r(88) = −0.21, p = 0.047), and Animal Fluency (r(88) = −0.23, p = 0.03).

The Interactive Effects of Elevated BMI and Cerebral Hypoperfusion on Cognitive Function

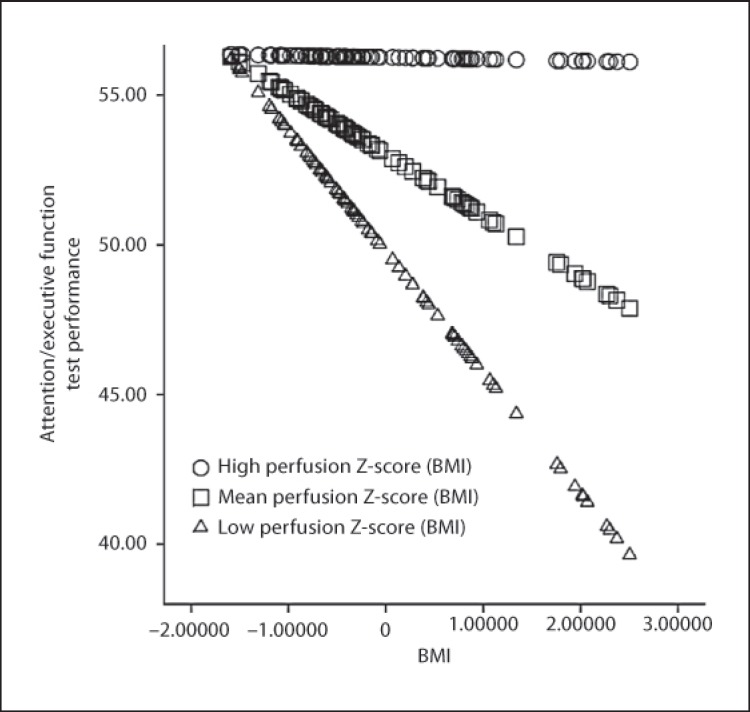

The interaction between BMI and global CBF-V (β = 0.22, ΔR2 = 0.04, p = 0.04) demonstrated predictive validity of attention/executive function after taking into account medical and demographic factors, BMI, and global CBF-V. The combined effect of elevated BMI and cerebral hypoperfusion exacerbated impairments in this domain. Figure 1 illustrates the interaction between BMI and global CBF-V. This pattern did not emerge for memory (p = 0.37) or language (p = 0.98).

Fig. 1.

The interactive effect of cerebral hypoperfusion and elevated BMI on attention/executive function among older adults with HF. Higher scores on the x-axis are reflective of elevated BMI and higher scores on the y-axis represent better test performance.

Discussion

Consistent with the extant literature, we found that obesity was prevalent in the current sample of HF patients. Past work has linked cerebral hypoperfusion and obesity with adverse psychosocial outcomes in persons with HF [17]. The current study extends these findings by demonstrating that in addition to separate effects of reduced CBF and elevated BMI, their combination is associated with additional cognitive deficits in HF.

We observed that elevated BMI and hypoperfusion are associated with reduced cognitive performance independent of comorbid medical conditions. This is consistent with past work linking high BMI with poor neurocognitive outcomes [19,20,21]. The exact mechanisms by which a combination of obesity and hypoperfusion exacerbates cognitive impairment in HF remain unclear. Possible explanations include increased risk for vascular comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension [34,35], or related vascular risk factors such as endothelial dysfunction, poor cardiovascular fitness, and systemic inflammation [36,37,38], which are common in obese persons. Recent research also raises the possibility that circulating biomarkers, including β-amyloid and brain-derived neurotrophic factor [39,40], might also influence neurocognitive outcomes in obese persons. These biomarkers are linked to cognitive performance in patient and healthy samples [41,42,43]. Similarly, genetic factors may also be involved, as recent studies have linked the Fat Mass and Obesity gene (FTO) with increased risk of AD [44]. Future work is needed to elucidate the specific mechanisms by which obesity affects brain functioning above and beyond HF-related pathology.

The pathophysiological effect of reduced CBF has been theorized to underlie cognitive impairment in HF patients [11]. Interestingly, obesity is also independently associated with reduced cerebral perfusion and metabolic activity [22]. It is unclear if vascular abnormalities, including reduced small vessel density, inflammation, arterial stiffness, and/or impaired vasodilation, cause hypoperfusion or reflect independent common causes of cognitive impairment in such persons [45,46]. For instance, cerebral hypoperfusion may help to explain the structural and functional neuroimaging abnormalities found in obese individuals [19]. As reduced cerebral perfusion has also been linked with poorer neurocognitive outcomes among persons with mild cognitive impairment [47], future research should investigate the neurological outcomes in HF patients with and without elevated BMI. In addition to these direct effects, studies should also examine the role of psychosocial risk factors on these outcomes. For example, obese individuals are often sedentary and physical activity is known to provide key benefits among HF patients, including improvements in cerebral hemodynamics [48].

The observed association between hypoperfusion and reduced scores on tests of attention/executive function and memory conforms to the reported sensitivity of these functions to vascular risk and vascular disease [10,11]. In contrast, BMI was associated with performance on attention/executive function and a higher-order language measure but not on memory tasks. Notably, only attention/executive function evidenced a significant CBF-BMI interaction effect. Thus, attention/executive function appears to be vulnerable to both risk factors and to their combined influence. Such sensitivity may reflect the fact that prefrontal brain regions that mediate executive functions are particularly susceptible to adverse effects of ischemia and subsequent structural damage [49]. Similarly, both obesity and HF are associated with impairments on tests of attention and executive function [11,20,21]. In contrast, the literature regarding the effects of obesity on memory is inconsistent [21,50]. Prospective studies are needed to clarify the effects of BMI on memory performance among HF patients, particularly since HF patients are frequently impaired in this domain [10].

The generalizability of the current findings is limited in several ways. First, the cross-sectional design does not inform about the contribution of BMI or cerebral perfusion to cognitive outcomes over time. Similarly, although BMI is a practical and commonly used index of obesity, it is a coarse measure. Future studies employing more detailed assessments such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) may be beneficial through its ability to distinguish between fat and lean mass. More precise and detailed measures of cerebral perfusion (e.g. arterial spin labeling, positron emission tomography) may also provide details of regional variations in CBF that might not be detected using transcranial Doppler. Finally, future studies should also explore the influence of clinical comorbidities common to obese and HF patients (i.e. sleep apnea) on cognitive function, as such factors may also contribute to cerebral hypoperfusion and subsequent cognitive impairment in this population.

In summary, this study demonstrates that cerebral hypoperfusion and obesity are associated with reduced attention/executive function among older adults with HF and that cognitive deficits are exacerbated by a combination of these factors. These findings have important clinical implications, as weight loss may alleviate cognitive dysfunction and remove at least one factor that exacerbates the adverse effects of hypoperfusion that accompanies HF.

Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work included National Institutes of Health grants DK075119 and HLO89311. N.R. is also supported by National Institutes of Health grant R37 AG011230.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2012 update. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalization among patients in Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Hellermann-Homan JP, Killian J, Yawn BP, Jacobsen SJ. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;292:344–350. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alosco ML, Spitznagel MB, Cohen R, Sweet LH, Colbert LH, Josephson R, Waechter D, Hughes J, Rosneck J, Gunstad J. Cognitive impairment is independently associated with reduced instrumental ADLs in persons with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27:44–50. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e318216a6cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett SJ, Oldridge NB, Eckert G, Embree JL, Browning S, Hou N, Chui M, Deer M, Murray MD. Comparison of quality of life measures in heart failure. Nurs Res. 2003;52:207–216. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu C, Winblad B, Marengoni A, Klarin I, Fastbom J, Fratglioni L. Heart failure and risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1003–1008. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roman G. Vascular dementia prevention: a risk factor analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20:91–100. doi: 10.1159/000089361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogels RLC, van der Flier WM, van Harten B, Gouw AA, Scheltens P, Schroeder-Tanka JM, Weinstein HC. Brain magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogels RL, Scheltens P, Schroeder-Tanka JM, Weinstein HC. Cognitive impairment in heart failure: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pressler SJ, Subramanian U, Kareken D, Perkins SM, Gradus-Pizlo I, Suave MJ, Ding Y, Kim J, Sloan R, Jaynes H, Shaw RM. Cognitive deficits in chronic heart failure. Nurs Res. 2010;59:127–139. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181d1a747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferson A, Poppas A, Paul R, Cohen R. Systemic hypoperfusion is associated with executive dysfunction in geriatric cardiac patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alosco ML, Spitznagel MB, van Dulmen M, Raz N, Cohen R, Sweet LH, Colbert LH, Josephson R, Hughes J, Rosneck J, Gunstad J. The additive effects of type-2 diabetes on cognitive function in older adults with heart failure. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:348054. doi: 10.1155/2012/348054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuccala G, Marzetti E, Cesari M, Lo Monaco MR, Antonica L, Cocchi A, Carbonin P, Bernabel R. Correlates of cognitive impairment among patients with heart failure: results of a multicenter survey. Am J Med. 2005;118:406–502. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baena-Diez JM, Byram AO, Grau M, Gomex-Fernandez C, Vidal-Solsona M, Ledesma-Ulloa G, Gonzalez-Casafont I, Vasquez-Lazo J, Subirana I, Schroder H. Obesity is an independent risk factor for heart failure: Zona Franca Cohort study. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:760–764. doi: 10.1002/clc.20837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapoor JR, Heidenrech PA. Obesity and survival in patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function: a U-shaped relationship. Am Heart J. 2010;159:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryu W, Lee S, Kim CK, Kim BJ, Yoon B. Body mass index, initial neurological severity and long-term mortality in ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32:170–176. doi: 10.1159/000328250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evangelista LS, Moser DK, Westlake C, Hamilton MA, Fonarow GC, Dracup K. Impact of obesity on quality of life and depression in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:750–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luchsinger JA, Cheng D, Tang MX, Schupf N, Mayeux R. Central obesity in the elderly is related to late-onset Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:101–105. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318222f0d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunstad J, Paul RH, Cohen RA, Tate DF, Spitznagel MB, Grieve S, Gordon E. Relationship between body mass index and brain volume in healthy adults. Int J Neurosci. 2008;118:1582–1593. doi: 10.1080/00207450701392282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunstad J, Paul RH, Cohen RA, Tate DF, Spitznagel MB, Gordon E. Elevated body mass index is associated with executive dysfunction in otherwise healthy adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunstad J, Lhotsky A, Wendell CR, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB. Longitudinal examination of obesity and cognitive function: results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;34:222–229. doi: 10.1159/000297742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willeumier K, Taylor D, Amen D. Elevated BMI is associated with decreased blood flow in the prefrontal cortex using SPECT imaging in healthy adults. Obesity. 2011;19:1095–1097. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dikmen S, Heaton R, Grant I, Temkin N. Test-retest reliability of the Expanded Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5:346–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen R. The Neuropsychology of Attention. New York: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW. Neuropsychological Assessment. ed 4. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B. The FAB: a frontal assessment battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55:1621–1626. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delis D, Kramer J, Kaplan E, Ober B. California Verbal Learning Test-Second Edition: Adult Version. Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawkins KA, Sledge WH, Orlean JE, Quinlan DM, Rakfeldt J, Huffman RE. Normative implications of the relationship between reading vocabulary and Boston Naming Test performance. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1993;8:525–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris J, Heyman A, Mohs R, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, Mellits ED, Clark C. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bulas D, Jones A, Seibert J, Driscoll C, O'Donnell R, Adams RJ. Transcranial Doppler (TCD) screening for stroke prevention I sickle cell anemia: pitfalls in technique variation. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30:733–738. doi: 10.1007/s002470000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owega A, Klingelhofer J, Sabri O, Kunert HJ, Albers M, Sab H. Cerebral blood flow velocity in acute schizophrenic patients: a transcranial Doppler ultrasonography study. Stroke. 1998;29:1149–1154. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.6.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kodl CT, Seaquist ER. Cognitive dysfunction and diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:494–511. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paglieri C, Bisbocci D, Caserta M, Rabbia F, Bertello C, Canadè A. Hypertension and cognitive function. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2008;30:701–710. doi: 10.1080/10641960802563584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teunissen CE, van Boxtel MP, Bosma H, Bosmans E, Delanghe J, De Bruijn C, Wauters A, Maes M, Jolles J, Steinbusch HW, de Vente J. Inflammation markers in relation to cognition in a healthy aging population. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;134:142–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colcombe S, Kramer AF. Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:125–130. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Umemura T, Kawamura T, Umegaki H, Mashita S, Kanai A, Sakakibara T, Hotta N, Sobue G. Endothelial and inflammatory markers in relation to progression of ischaemic cerebral small-vessel disease and cognitive impairment: a 6-year longitudinal study in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:1186–1194. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.217380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balakrishnan K, Verdile G, Mehta PD, Beilby L, Nolan D, Galvao DA, Newton R, Gandy SE, Martins RN. Plasma AB42 correlates positively with increased body fat in healthy individuals. J Alzheimer Dis. 2005;8:269–282. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krabbe KS, Nielsen AR, Krogh-Madsen R, Plomgaard P, Rasmussen P, Erikstrup C, Fischer CP, Lindegaard B, Petersen AM, Taudorf S, Secher NH, Pilegaard H, Bruunsgaard H, Pedersen BK. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:431–438. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gunstad J, Spitznagel M, Keary T, Glickman E, Alexander T, Karrer J, Stanek K, Reese L, Juvancic-Heitzel J. Serum leptin levels are associated with cognitive function in older adults. Brain Res. 2008;1230:233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leahey TM, Myers TA, Gunstad J, Glickman E, Spitznagel MB, Alexander T, Juvancic-Heltzel J. AB40 is associated with cognitive function, body fat and physical fitness in healthy older adults. Nutr Neurosci. 2007;10:205–209. doi: 10.1080/10284150701676156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laske C, Stransky E, Leyhe T, Eschweiler GW, Wittorf A, Richartz E, Bartels M, Buchkremer G, Schott K. Stage-dependent BDNF serum concentrations in Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm. 2005;113:1217–1224. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0397-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keller L, Xu W, Wang HX, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L, Graff C. The obesity related gene, FTO, interacts with APOE, and is associated with Alzheimer's disease risk: a prospective cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;23:461–469. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arkin JM, Alsdorf R, Bigornia S, Lamisano J, Beal R, Istfan N, Hess D, Apovian CM, Gokce N. Relation of cumulative weight burden to vascular endothelial dysfunction in obesity. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zebekakis PE, Nawrot T, Thijs L, Balkestein EJ, Heijden-Spek J, Van Bortel LM, Struijker-Boudier HA, Safar ME, Staessen JA. Obesity is associated with increased arterial stiffness from adolescence until old age. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1839–1846. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000179511.93889.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, Golob E, Bert A, Nie K, Chu Y, Dick MB, Mandelkern M, Su MY. Alterations in regional brain volume and individual MRI-guided perfusion in normal control, stable mild cognitive impairment, and MCI-AD converter. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;2:35–45. doi: 10.1177/0891988708328212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haykowsky MJ, Liang Y, Pechter D, Jones L, McAlister FA, Clark AM. A meta-analysis of the effect of exercise training on left ventricular remodeling in heart failure patients: the benefit depends on the type of training performed. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2329–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Acker JD. Hypertension and the brain: vulnerability of the prefrontal regions and executive functions. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1169–1180. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corley J, Gow AJ, Starr JM, Deary IJ. Is body mass index in old age related to cognitive abilities. The Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:867–875. doi: 10.1037/a0020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]