Summary

Myocardial progenitor development involves the migration of cells to the anterior lateral plate mesoderm (ALPM) where they are exposed to the necessary signals for heart development to proceed. Whether the arrival of cells to this location is sufficient, or whether earlier signaling events are required, for progenitor development is poorly understood. Here we demonstrate that in the absence of Aplnr signaling, cells fail to migrate to the heart-forming region of the ALPM. Our work uncovers a previously uncharacterized cell-non-autonomous function for Aplnr signaling in cardiac development. Furthermore, we show that both the single known Aplnr ligand, Apelin, and the canonical Gαi/o proteins that signal downstream of Aplnr are dispensable for Aplnr function in the context of myocardial progenitor development. This novel Aplnr signal can be substituted for by activation of Gata5/Smarcd3 in myocardial progenitors, suggesting a novel mechanism for Aplnr signaling in the establishment of a niche required for the proper migration/development of myocardial progenitor cells.

Keywords: Myocardial Progenitors, Apelin Receptor, Gastrulation, Zebrafish

Introduction

A key step to organogenesis is the proper recruitment and differentiation of progenitors that form the mature cell types needed for organ development and function. Cardiovascular progenitor cells (CPCs) are the building blocks of the heart, and have the potential to form cardiomyocytes, endocardium and smooth muscle cells (Kattman et al., 2006; Moretti et al., 2006). CPCs are among the first to migrate during gastrulation, ultimately reaching bilateral regions of the anterior lateral plate mesoderm (ALPM) (Wu et al., 2008). Fate mapping studies in multiple vertebrate models have shown that CPCs arise from a fixed location in the pregastrulation embryo (reviewed in (Evans et al., 2010)). In zebrafish, cells fated to become cardiomyocytes arise from bilateral regions within the first few tiers of cells at the embryonic margin of the 4–6 hours post-fertilization (hpf) embryo, displaced 60–140° relative to the dorsal side of the embryo (Keegan et al., 2004; Stainier et al., 1993). Localization of cells to this “heart field” region of the pregastrula embryo can instruct later myocardial fate, as donor cells transplanted to this area can form cardiomyocytes in vivo (Lee et al., 1994). Upon arrival at the ALPM, multiple signals lead to initiation of cardiogenesis (reviewed in (Evans et al., 2010)), with expression of Nkx2.5, encoding an NK-class homeodomain transcription factor, being the earliest marker of myocardial progenitors in zebrafish and other vertebrates (Chen and Fishman, 1996; Komuro and Izumo, 1993; Lints et al., 1993; Tonissen et al., 1994).

It is apparent that myocardial progenitor cells arise from a specific location in the embryo and migrate during gastrulation to the ALPM, where they receive signals necessary for differentiation into cardiomyocytes. However, it remains to be determined whether cells fated to form the myocardium require additional signals during gastrulation to effectuate proper heart development, or if it is sufficient that cells reach the ALPM. Explant experiments, primarily done in the chick embryo, have yielded conflicting results on this question (reviewed in (Yutzey and Kirby, 2002)). Whereas some studies argue that cells exist in the early gastrula that are capable of forming cardiomyocytes regardless of later location in the embryo (Auda-Boucher et al., 2000; Lopez-Sanchez et al., 2009), others suggest that ultimate localization to the ALPM is sufficient for cardiac differentiation (Inagaki et al., 1993; Tam et al., 1997). A lack of mutants that specifically affect early myocardial progenitor development, and markers to isolate and characterize these cells, has hindered progress on this key question of early heart development. Members of the Mesp basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family are essential for cardiogenesis in mouse and Ciona intestinalis, and can promote myocardial differentiation in embryonic stem cells (reviewed in (Bondue and Blanpain, 2010)). Mesp function in mice is required for proper migration of cardiac progenitors during gastrulation. Perturbations in BMP, FGF, Wnt (both canonical and non-canonical), and Nodal signaling prior to and during gastrulation lead to later deficits in development of Nkx2.5-expressing myocardial progenitors (Reifers et al., 2000; Reiter et al., 2001; Ueno et al., 2007). However, as embryos exhibit gross developmental defects when these pathways are manipulated, it is difficult to uncouple function in myocardial progenitor development from general patterning defects. Nevertheless, these results suggest that CPC potential and behaviour is influenced during gastrulation.

Our group has previously described a zebrafish mutant, grinch (grn), in which there is a striking and specific deficit in myocardial progenitors (Scott et al., 2007). Characterization of the mutant showed that there was a decrease in, or in the most severe cases a loss of, nkx2.5-expressing cells. The grn mutation was mapped to the gene encoding Angiotensin II receptor-like 1b (aplnrb, apj, msr1, agtrl1b; referred to as aplnrb in this study), a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). Both loss of aplnrb and overexpression of apelin (which encodes the only known Aplnr ligand (Tatemoto et al., 1998)) during early gastrulation resulted in a heartless phenotype in zebrafish (Scott et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2007). Aplnrb shares functional properties with chemokine receptors (Zou et al., 2000), and has been shown to promote angiogenesis in several contexts (Cox et al., 2006; Kasai et al., 2004; Sorli et al., 2007). The loss of heart following Apelin overexpression therefore suggested a chemotactic role for Aplnr/Apelin signaling to guide migration of myocardial progenitor cells to the ALPM during gastrulation. Both apelin overexpression and morpholino-mediated knockdown has been shown to affect migration of cells during gastrulation (Scott et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2007). However, knockdown of apelin did not fully recapitulate the grn/aplnrb heartless phenotype. This suggested that Aplnrb may not simply act via Apelin signaling in cardiac progenitor development, and left as an open question the mechanism of the aplnrb heartless phenotype.

In this study we carried out a detailed analysis of the aplnrb loss-of-function phenotype to elucidate the mechanism through which Aplnr signaling regulates vertebrate heart development. We find defects in a specific region of the aplnrb mutant ALPM, coincident with the site of cardiac development. By tracking cells as they migrate from the heart field region of the early embryo, we find that these cells fail to reach the ALPM in the absence of aplnrb function due to a defect in the initiation of migration, resulting in the complete absence of cells in the heart-forming region. Unexpectedly, via transplantation analysis we find that Aplnrb function is required non-autonomously, in cells not destined to form cardiomyocytes, for proper myocardial progenitor development. This occurs independently of classic heterotrimeric G-protein signaling downstream of the GPCR Aplnrb. Finally, initial work suggests the activation of the cardiac chromatin remodeling complex, cBAF, in cardiac progenitors as a consequence of Aplnr signaling. This study therefore identifies a novel, non-autonomous function for Aplnr signaling to support proper myocardial progenitor development. Interestingly, this signal may provide a niche for proper CPC development and migration.

Results

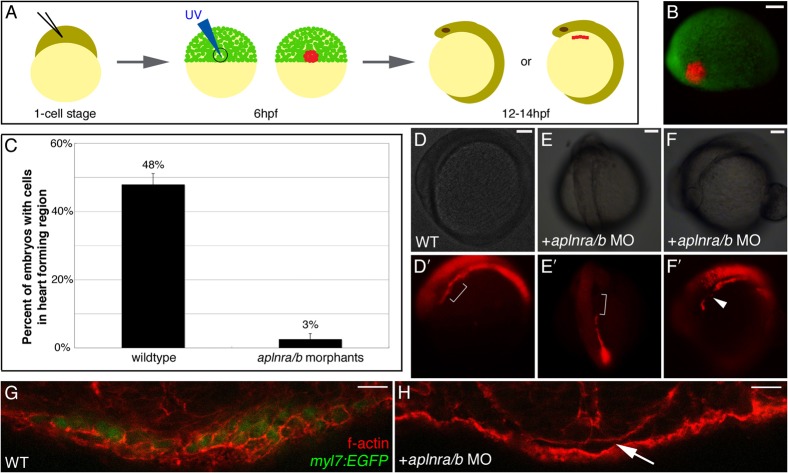

Cells from the pregastrula heart field fail to reach the ALPM in aplnra/b morphant embryos

Our previous analysis suggested defects in ALPM formation in aplnrb morphants (morpholino-injected embryos) and mutants (Scott et al., 2007). To further characterize ALPM development, expression of additional ALPM markers was examined in aplnrb mutants. RNA in situ hybridization analysis demonstrated that, along with loss of nkx2.5 expression, there is a decrease in expression of spi1 and the more posterior domains of fli1 and tal1 in the ALPM, marking myeloid and presumed endocardial progenitors, respectively (supplementary material Fig. S1). This decrease in gene expression in aplnrb mutants may reflect a failure of cells to reach the APLM during development. Alternatively, cells may reach the ALPM but fail to differentiate into the proper cell types. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we performed lineage tracing to determine whether cells from the lateral embryonic margin migrate to the ALPM. For these experiments, the photoconvertible protein KikGR was employed. KikGR normally fluoresces with spectral characteristics similar to EGFP, however after exposure to UV light undergoes a permanent change in its fluorophore such that it fluoresces as a red fluorescent protein (Hatta et al., 2006). To obtain a more complete loss of Aplnr activity, we employed morpholinos (MOs) to inhibit aplnrb along with its paralog aplnra (Tucker et al., 2007). We have previously found that co-injection of these MOs results in a robust heartless phenotype and recapitulates loss of gene expression observed in the ALPM of aplnrb mutants (Scott et al., 2007; supplementary material Fig. S2). One-cell stage wildtype and aplnra/aplnrb MO-injected embryos were co-injected with mRNA encoding KikGR. At 6hpf, a cluster of about 50 cells at the lateral embryonic margin (displaced 900 from the shield) was photoconverted via exposure to UV light (Fig. 1B). Embryos were subsequently scored at 12–14hpf (6–10 somite stage) for the presence of photoconverted cells that had migrated to the heart-forming region of the ALPM (Fig. 1A). In 48% of wildtype embryos, cells from the lateral margin were found as a continuous stripe throughout the lateral plate mesoderm, beginning at the ALPM and extending posterior to the level of the anterior somites (Fig. 1D,D′). Photoconversion of lateral margin cells in aplnra/b morphant embryos similarly often resulted in a lateral stripe of cells being evident on one side of the embryo. However, we found a striking and significant difference (p = 0.001) between wildtype and aplnra/b morphant embryos in the presence of photoconverted cells in the heart-forming region of the ALPM. In aplnra/b morphants, cells were rarely evident in this area (brackets in Fig. 1E′ compared to wildtype in Fig. 1D′). In some cases, cells were found both anterior and posterior to this area but were missing specifically form the heart-forming region (arrowhead in Fig. 1F′). In the few instances that cells were found in the ALPM, their organization into a stripe was highly disrupted (supplementary material Fig. S3). Contribution of photoconverted cells to the heart-forming region of the ALPM was thus markedly reduced in morphant embryos (27/57 in wildtype versus 3/104 in aplnra/b morphants, Fig. 1C). These data demonstrate that the deficit in myocardial progenitor development in aplnra/b morphants reflects the failure of cells from the lateral embryonic margin to reach the ALPM.

Fig. 1. Cells from the lateral embryonic margin fail to reach the heart-forming region in aplnra/b morphants.

(A) Schematic of photoconversion method. mRNA encoding KikGR is injected at the 1-cell stage. Cells at the lateral embryonic margin (90° from dorsal, anatomically marked by the shield) are photoconverted by UV light at 6hpf. Embryos are scored at 12–14hpf for the presence of cells in the heart-forming region of the ALPM. (B) Merged fluorescent views of 6hpf embryo following photoconversion of lateral margin cells. (C) Graph of percentage of embryos with photoconverted cells that reach the heart-forming region. In wildtype embryo labeled cells are found in the lateral plate mesoderm (D′), including the heart-forming region (bracket in D′). In aplnra/b morphants labeled cells are found in the lateral plate mesoderm but fail to extend anteriorly to the heart-forming region (bracket in E′) or are excluded from the heart-forming region (arrowhead in F′) while cells are found both and anterior and posterior to this region. (D–F) are bright field images of embryos in (D′-F′). (D,F) lateral views with anterior to the left, (E) dorsal view with anterior to the top. For (C) N = 3, n = 57 for WT; N = 4, n = 104 for aplnra/b morphants; p = 0.001. (G,H) cross-sections through the ALPM of 20hpf wildtype (WT) and aplnra/b morphant myl7:EGFP embryos, respectively, stained with rhodamine-phalloidin to visualize cells. EGFP+ cardiac progenitors are present in wildtype embryos (G) while there is and absence of cells in the heart-forming region in aplnra/b morphants (arrow in H). See also supplementary material Fig. S3. Scale bars represent 100μm (B, D/D′, E/E′ and F/F′), 17μm (G) and 12μm (H).

Portions of the ALPM are absent in aplnra/b morphants

To determine whether cells are present in the heart-forming region of the ALPM in aplnra/b morphants, we sectioned cardiomyocyte-specific myl7:EGFP (Huang et al., 2003) transgenic embryos at 20hpf and imaged cross-sections stained for filamentous Actin. Given the failure of lateral margin cells to reach the heart-forming region of the ALPM following loss of Aplnr signaling, it is possible that cells from other regions of the early embryo migrate to this area in their place. At 20hpf, the bilateral fields of cardiac mesoderm are folded epithelial sheets that have begun their migration to the midline (Trinh and Stainier, 2004). Sections were selected for analysis based on the absence of head structures (such as brain ventricles) and the notochord to demarcate anterior and posterior ALPM boundaries, respectively. In wildtype embryos the expected folded epithelial sheet and cardiac-specific myl7:EGFP signal was observed (Fig. 1G). In contrast, there was a marked absence of cells in the ALPM of aplnra/b morphants (Fig. 1H). These data suggest that in aplnra/b morphants, and aplnrb mutants, there are no cells in the region of the ALPM that typically forms cardiac tissue.

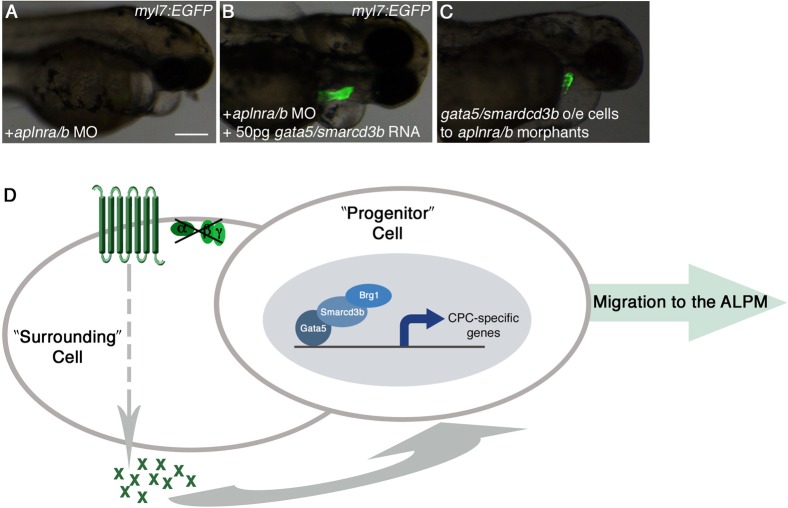

Lateral margin cells exhibit early migration defects

To explore further the migration defect seen in the absence of Aplnr signaling, we performed time-course analysis of wildtype and aplnra/b morphant embryos. Cells were photoconverted as described above and embryos were imaged over time from shield stage (6hpf) to bud stage (10hpf), when gastrulation movements have been largely completed (Warga and Kimmel, 1990). Upon gross observation we saw the typical migration pattern in wildtype embryos with a streak of cells moving toward the animal pole (arrow in Fig. 2A,B). In aplnra/b morphant embryos, we found the leading cells of the migrating group to be absent (arrow in Fig. 2D,E). Importantly, cells in the leading streak are those that will form the ALPM (Sepich et al., 2005; Yin et al., 2009) and are found in the appropriate location in wildtype embryos (arrowhead in Fig. 2C) but not in aplnra/b morphants (arrowhead in Fig. 2F) at bud stage. We next examined this in more detail to determine when defects in migration are first apparent in aplnra/b morphants. By imaging embryos at higher magnification and at more frequent time intervals, we found that labeled cells exhibited a delay in the initiation of migration toward the animal pole in aplnra/b morphants. In contrast to wildtype embryos in which migration is well underway by 70% epiboly (Fig. 2G), cells in aplnra/b morphant embryos do not start migrating until roughly 85% epiboly (Fig. 2J; supplementary material Fig. S4), a lag of 1.0 to 1.5 hours. Our data therefore suggest that cells from the lateral embryonic margin in aplnra/b morphants fail to reach the ALPM due to a defect or delay in the initiation of migration towards the animal pole of the embryo.

Fig. 2. Cells from the lateral embryonic margin display a defect in the initiation of migration.

(A–F) Embryos injected with KikGR RNA were photoconverted at shield stage to mark cells in the lateral margin. Representative images of wildtype and aplnra/b morphant embryos at 70% epiboly (7.5hpf), 80% epiboly (8.5hpf), and bud (10hpf) stages. Arrows indicate leading streak of migrating cells in wildtype embryos and their absence in morphant embryos. Arrowheads indicate cells in the heart-forming region of wildtype embryos and absence of cells in morphants. (G–L) Time-lapse image of one wildtype and one aplnra/b morphant embryo during gastrulation demonstrating a delay in the initiation of migration of morphant cells. Corresponding images of the embryos are shown in (G′-L′) for each fluorescent image. Scale bar represents 100μm (A).

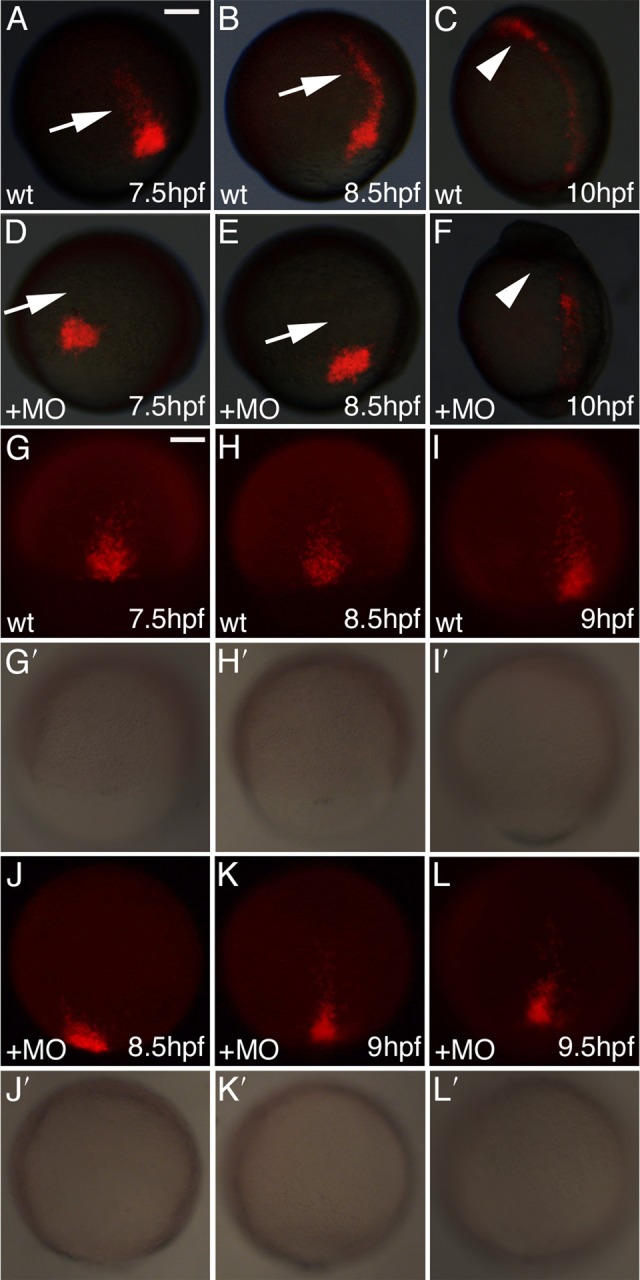

Aplnr signaling functions cell-non-autonomously in the development of cardiomyocytes

We next performed transplantation analysis to determine whether Aplnr signaling functions cell-autonomously or cell-non-autonomously in the development of cardiomyocytes. It has been suggested that Aplnr signaling modulates a chemotactic cue that attracts cardiac progenitors to the heart-forming region of the ALPM (Scott et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2007). If this were the case, a cell-autonomous role for aplnrb would be expected. While we have previously shown a decreased ability of aplnrb morphant cells to contribute to the heart (Scott et al., 2007), a possible non-autonomous role for this gene was not evaluated in these studies.

Cells from wildtype or aplnra/b MO-injected donor embryos harboring a myl7:EGFP transgene were transplanted into the embryonic margin of wildtype or aplnra/b morphant host embryos. Transplant embryos were then scored at 48hpf for EGFP-positive cells, which would indicate donor cells that have formed cardiomyocytes. In control (wildtype donor to wildtype host) transplants, differentiated cardiomyocytes were evident in 19% of host embryos, in agreement with previously published work (Scott et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2008; Fig. 3A,E). As expected, aplnra/b morphant cells had a greatly reduced capacity to differentiate into cardiomyocytes when placed in morphant host embryos (1% of tranplants were EGFP+, Fig. 3B,E), recapitulating the aplnra/b phenotype. Surprisingly, wildtype donor cells were rarely able to differentiate into cardiomyocytes in aplnra/b morphant hosts (2% of tranplants were EGFP+, n = 190, Fig. 3C,E), whereas aplnra/b morphants cells had the capacity to differentiate into cardiomyocytes in wildtype hosts, albeit to a lesser extent than wildtype donor cells (13% of transplants were EGFP+, n = 190; Fig. 3D,E). Our results demonstrate an unappreciated cell-non-autonomous role for Aplnr signaling in cardiomyocyte development.

Fig. 3. Aplnr signaling functions cell-non-autonomously in the development of cardiomyocytes.

Transplantation of wildtype (WT) or aplnra/b MO-injected (+MO) myl7:EGFP donor embryos to the margin WT or aplnra/b MO-injected host embryos was carried out at 4hpf. (A–D) Representative host embryos at 2dpf following transplantation; lateral view, anterior to left. (C) wildtype cells are unable to contribute to the heart in aplnra/b morphant host embryos, whereas aplnra/b morphant cells are able to contribute to the heart in wildtype hosts (D). (E) Graph of percentage of host embryos with contribution from myl7:EGFP donor cells. N = 5, n = 236 for wildtype donors and hosts; N = 4, n = 130 for aplnra/b morphant donors and hosts; N = 4, n = 190 for wildtype donors and aplnra/b morphant hosts; N = 3, n = 190 for aplnra/b morphant donors and wildtype hosts. Views in (A–D) are lateral views, with anterior to the left. Scale bar represents 200μm (A).

We next wished to confirm that the non-autonomous function seen in aplnra/b morphants is specific to Aplnr activity and not secondary to a host embryo heartless phenotype. We utilized gata5/6 morphants, in which myocardial differentiation is fully compromised (Holtzinger and Evans, 2007). When transplants were performed as described above we found that Gata5/6 activity is required cell-autonomously in cardiomyocyte development. Wildtype cells were able to contribute to heart in 18% of wildtype and 11% of gata5/6 morphant hosts, whereas gata5/6 morphant cells were unable to contribute to the heart in wildtype embryos (0/83 hosts) (data not shown). These data confirm that the non-autonomous function seen in aplnra/b morphants is specific to the loss of Aplnr activity, and not a general consequence of an absence of host cardiac progenitors.

Role of Apelin in Aplnr signaling during cardiac progenitor development

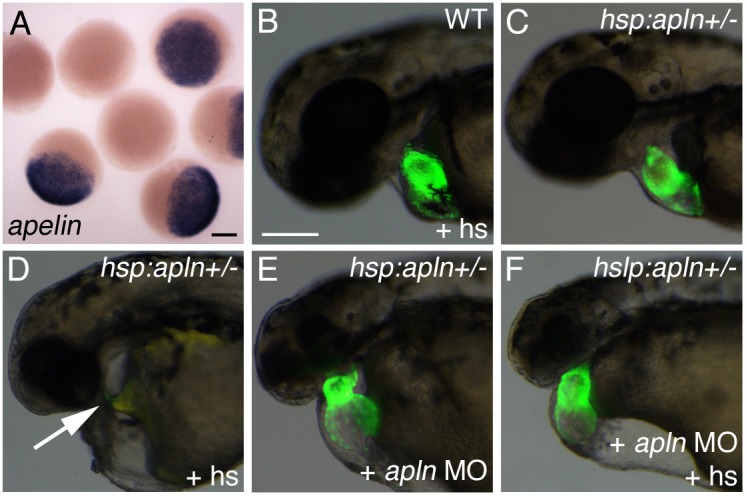

With our data revealing a non-autonomous role for Aplnr in cardiomyocyte development, we decided to revisit the role of the Apelin ligand in this process. While injection of aplnra/b MO leads to embryos lacking cardiac tissue, injection of apelin MO fails to recapitulate this heartless phenotype, with only a reduced heart size evident in the most severe cases ((Zeng et al., 2007), Fig. 4E). A trivial explanation for this discrepancy could be that the apelin MOs used do not fully inhibit Apelin function. To determine if this may be the case, we injected apelin MO into hsp:apelin transgenic embryos and compared the phenotype of the embryos with or without the induction of apelin over-expression. Heat-shock of hsp:apelin embryos prior to 6hpf greatly increased apelin expression compared to wildtype siblings (Fig. 4A). As we have previously found, hsp:apelin embryos heat-shocked at 4hpf resulted in a heartless phenotype (Scott et al., 2007; Fig. 4D). Injection of apelin MO resulted in a slight reduction in the size of the heart (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, when hsp:apelin transgenic embryos injected with apelin MO were heat-shocked, they re-capitulated the apelin morphant phenotype (small heart) rather than the apelin over-expression (heartless) phenotype (Fig. 4F). As the hsp:apelin transgene expresses, by RNA in situ hybridization, greatly elevated levels of apelin, this strongly suggested that the amount of apelin MO injected was sufficient to suppress the endogenous apelin transcript levels. Therefore, in wildtype embryos injection of apelin MO likely results in a complete knockdown of endogenous Apelin, and lends further support to the model that Apelin may not be the functional ligand for Aplnr signaling during myocardial progenitor development.

Fig. 4. Apelin is not necessary for the development of cardiomyocytes.

(A) Embryos produced from crossing hsp70:apln+/- and wildtype fish showing robust up-regulation of apelin expression by RNA in situ hybridization following heat shock in embryos carrying the hsp70:apln transgene. (B) Wildtype fish are unaffected by heat-shock (+hs). (C) Unshocked hsp70:apln+/- embryos are phenotypically wildtype. (D) Overexpression of apelin leads to a loss in cardiac tissue (arrow shows empty cardiac region). (E) Injection of apelin MO leads to a heart that is present, but dismorphic. (F) Injection of apelin MO followed by heat shock of hsp70:apln embryos results in phenocopy of the apelin morphant heart phenotype. Scale bars represent 200μm (A and B, B scale bar is for images B–F).

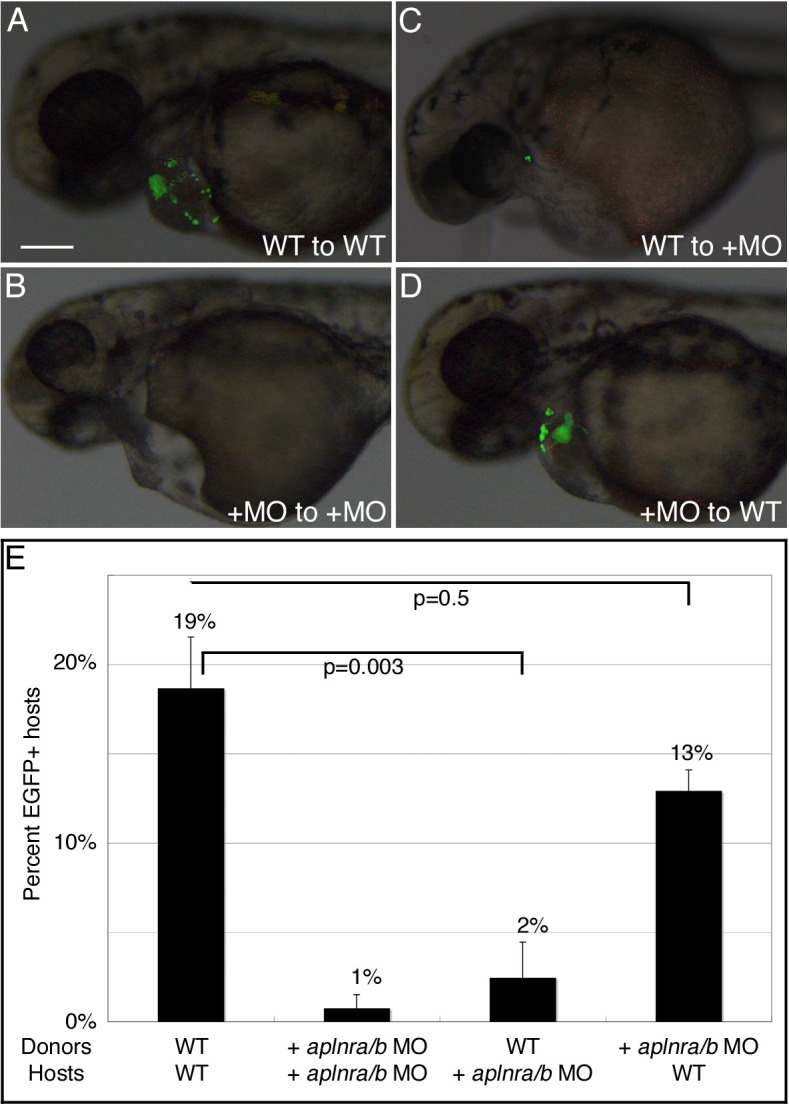

Aplnra/b signaling is Gαi/o protein-independent in cardiomyocyte development

The demonstration of a potential Apelin-independent role of Aplnrb in cardiac progenitor development next led us to examine the nature of Aplnrb signaling. In vitro, the human APLNR has been shown to signal in a classical heterotrimeric G-protein mediated fashion via the Gαi/o class of Gα proteins (Masri et al., 2002). We sought to determine whether Aplnr signaling functions through Gαi/o proteins in the development of cardiomyocytes in vivo. Pertussis toxin (PTX) is a potent inhibitor of Gαi/o signaling and acts by uncoupling Gαi/o proteins, and presumably their βγ subunits, from associated GPCRs (Codina et al., 1983). We first injected RNA encoding PTX at the 1-cell stage to globally inhibit Gαi/o-mediated signaling. Global over-expression of PTX recapitulated the aplnra/b morphant embryo heartless phenotype (Fig. 5B,C). However, Gαi/o proteins both act downstream of multiple GPCRs and have been shown to regulate aspects of Hedgehog and Wnt signaling (Ogden et al., 2008; Slusarski et al., 1997). We could therefore not conclude from these results that the loss of cardiac tissue following PTX overexpression was specifically due to inhibition of Gαi/o-mediated Aplnr signaling.

Fig. 5. Aplnr activity is independent of Gαi/o proteins in cardiomyocyte development.

(A–C) Bright field images of wildtype (WT), aplnra/b morphant, and PTX overexpressing myl7:EGFP embryos at 2dpf. (A′–C′) Fluorescent images of embryos in (A–C), (A″–C″) are overlays of (A–C) and (A′–C′). Overexpression of PTX (C) recapitulates the aplnra/b morphant (B) cardiac phenotype. (D–F) Transplantation of myl7:EGFP donor cells from WT or PTX overexpressing cells to WT or PTX overexpressing host embryos at 4hpf was carried out. Hosts were subsequently scored at 2dpf for EGFP +′ve donor cells in the heart. (D–E) PTX overexpressing cells are able to contribute to the heart in wildtype embryos (D), and wildtype cells are able to contribute to the heart in PTX overexpressing host embryos (E), suggesting that Gαi/o proteins are not downstream of Aplnr signaling in cardiomyocyte development. (F) Graph showing percentage of host embryos with contribution from myl7:EGFP donor cells in transplants performed. N = 5, n = 236 for wildtype donors and hosts; N = 2, n = 80 for PTX O/E donors and hosts; N = 3, n = 158 for wildtype donors and PTX O/E hosts; N = 3, n = 216 for PTX O/E donors and wildtype hosts. O/E = overexpressing. (G,H) Cross sections through the ALPM of 20hpf myl7:EGFP wildtype and PTX overexpressing embryos. The ALPM is evident at the level of the heart-forming region following PTX addition (arrow in H) but cells fail to differentiate into cardiomyocytes as noted by the absence of EGFP +′ve cells. (A–E) are lateral views, with anterior to the left. Scale bars represent 200μm (A and D), 17μm (G) and 22μm (H).

To further examine whether Gαi/o proteins are the major effectors of the Aplnr signaling pathway, we performed transplant analyses as described above using wildtype and PTX over-expressing embryos as both donors and hosts. In control experiments where PTX RNA-injected donor cells and host embryos were used, we observed no EGFP+ donor cells (n = 80). Transplantation of PTX over-expressing cells to wildtype host embryos revealed a minor cell-autonomous role for Gαi/o-mediated signaling in cardiac differentiation, with a reduction in transplant embryos with EGFP-positive cells being observed (EGFP+ cells in 13% of hosts, n = 216, Fig. 5D,F). Surprisingly, and in contrast to aplnra/b morphant transplant experiments, we found that wildtype cells were able to differentiate into cardiomyocytes after being transplanted into PTX over-expressing host embryos (EGFP+ cells in 12% of hosts, n = 158, Fig. 5E,F). These data suggest that the cell-non-autonomous effect of Aplnr signaling in cardiomyocyte development is independent of, or at least not fully dependent upon, signaling through Gαi/o proteins. In addition, we found that wildtype cells were able to contribute to heart in host embryos in which Gβγ subunit activity was inhibited by injection of RNA encoding the C-terminal fragment of GRK2 (Koch et al., 1994). In these experiments, EGFP+ cells were evident in 12% of hosts (n = 75; data not shown), further supporting a Gαi/o protein-independent mechanism for Aplnr signaling.

Given the differences in the autonomy of Aplnr and Gαi/o function, we next sectioned myl7:EGFP embryos over-expressing PTX at 20hpf to examine the ALPM. Unlike what was observed in aplnra/b morphants, cells were present in the ALPM at the level of the heart-forming region in embryos injected with PTX RNA. However, these cells were unable to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, as noted by the absence of EGFP+ cells in myl7:EGFP transgenic embryos (arrow in Fig. 5H). Therefore, while global inhibition of Gαi/o protein signaling blocks differentiation of cells into cardiomyocytes, the autonomy and ultimate cause of this phenotype differs from that seen following aplnra/b knockdown. Taken together, these data suggest that Aplnr signaling acts via a mechanism independent of Gαi/o proteins in cardiac progenitor development (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6. Gata5/smarcd3b function downstream of Aplnr signaling to direct cells to the heart-forming region.

(A,B) Overexpression of gata5 and smarcd3b is able to rescue the aplnra/b morphant cardiac phenotype in myl7:EGFP embryos. (C) Cells from myl7:EGF embryos overexpressing gata5 and smarcd3b can contribute to the heart when transplanted into aplnra/b morphant embryos. (D) Working model for Aplnr signaling in cardiac progenitor development. Aplnr activity functions independently of Gαi/o proteins in the production of extracellular factor(s)/cue(s). These factor(s)/cue(s) act cell-non-autonomously upon neighboring cells in the lateral embryonic margin, wherein gata5/smarcd3b, as part of the cBAF complex, functions cell-autonomously, facilitating their migration to the ALPM for development into cardiac progenitors. Aplnr activity is not required in progenitor cells. o/e: overexpressing. Scale bar represents 200μm (A).

Aplnr signaling functions upstream of the cardiac BAF complex

Recent work published by our lab demonstrated that overexpression of gata5 and smarcd3b, two factors in a cardiac-specific chromatin remodeling complex (cBAF) effectively directed the migration of non-cardiogenic cells to the ALPM and their subsequent contribution to various cardiovascular lineages (Lou et al., 2011). As both Aplnr signaling and the cBAF complex influence the migration of cells to the heart-forming region of the ALPM, we investigated the relationship between these two activities. When gata5 and smarcd3b were overexpressed in aplnra/b morphant embryos in a myl7:EGFP transgenic background, we were able to rescue the aplnra/b heartless phenotype as demonstrated through the presence of EGFP+ cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6B). Additionally, when cells from myl7:EGFP embryos overexpressing gata5 and smarcd3b were transplanted into aplnra/b morphant host embryos, the cells were able to differentiate into cardiomyoctyes in a cell autonomous manner (Fig. 6C), with GFP+ cells in 18% (19/107) of host embryos. Taken together, these data suggest that the non-autonomous effects of Aplnr signaling may lead to the activation of the cBAF complex, which acts cell-autonomously ((Lou et al., 2011), this study) to guide the migration of cells to the heart-forming region of the zebrafish embryo (Fig. 6D).

Discussion

In previous studies of Aplnr signaling in zebrafish, a role for the migration of cells during gastrulation was inferred based on analysis of knockdown and global over-expression of Apelin (Scott et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2007). Here, we have conducted a detailed analysis of ALPM development in the absence of Aplnr signaling. Our data demonstrate a role for Aplnrb signaling in the migration of cells from the lateral embryonic margin to the heart-forming region of the embryo, likely through the activity of cBAF (Fig. 6D). In the absence of Aplnrb signaling, a discrete domain of the ALPM, which overlaps with the site of nkx2.5 expression, is devoid of cells. This effect on a confined region of the ALPM likely explains the cardiac specificity of the aplnrb mutant phenotype. Interestingly, we report here an unexpected cell-non-autonomous function for Aplnr signaling in heart development. Further, we show here that Aplnrb function in the context of cardiac progenitor development occurs via a Gαi/o protein-independent mechanism that is not dependent on the canonical Apelin ligand. The previous chemotactic model of Aplnrb function, in which it guides migrating cardiac progenitors to the ALPM via response to an Apelin gradient, therefore clearly must be revised.

It remains unclear why, despite the broad expression of aplnrb in gastrulating mesendoderm (Scott et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2007), migration of cardiac progenitors (and presumably their neighbours in the ALPM) is specifically affected in aplnrb mutants. Cells contributing to cranial vasculature, circulating blood, pectoral fin mesenchyme and pharyngeal pouches have been shown to arise from overlapping regions of the ALPM (Keegan et al., 2004). However, the pectoral fin and cranial vasculature form normally in aplnrb mutants (this study and (Scott et al., 2007)). Thus Aplnr function appears to be necessary for specific cell populations that are found in a mixed progenitor pool at the lateral embryonic margin. Our photoconversion analysis demonstrated that cells from the lateral embryonic margin fail to migrate to the ALPM in the absence of Aplnr signaling. This may be due to a delay in the initiation of migration of “leading edge” mesoderm towards the animal pole (“anterior” of the embryo). While we did observe the eventual migration of cells toward the animal pole in aplnra/b morphants, the nature and fate of these cells remains unclear. They may represent myocardial progenitors that have initiated migration at a later time than in a wildtype embryo. Alternatively, they may be more posterior LPM progenitors that are initiating migration at the correct time. In this latter scenario, myocardial progenitors may have never been specified and/or failed to gastrulate, instead accumulating at the embryonic margin or moving passively with neighboring cells. From this perspective it is interesting to note that myocardial progenitors are among the first cell types to involute during vertebrate gastrulation (Garcia-Martinez and Schoenwolf, 1993; Parameswaran and Tam, 1995). The timing of this event may be essential for later heart development by allowing migration to the ALPM or rendering myocardial progenitors competent to initiate cardiogenesis. In this regard, the ability of Gata5/Smarcd3 to rescue myocardial differentiation in aplnra/b morphants is instructive (see below).

Many signals affecting cardiac progenitor migration to the midline, after the onset of nkx2.5 expression, have been described, with perturbations resulting in cardia bifida (2 hearts, (Chen et al., 1996; Saga et al., 1999)). In the case of Aplnr signaling, mis-regulation of migration appears specific to a subset of gastrulating cells: those destined to reach the heart-forming region. This result is intriguing, as the molecular mechanisms regulating the migration of cardiac progenitors to the ALPM are poorly understood. Wnt3a/Wnt5a signaling has been shown to affect the path of cardiac progenitor migration in chick embryos, but not to affect cardiac progenitor specification (Sweetman et al., 2008; Yue et al., 2008). The non-canonical Wnt/planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling pathway regulates convergence and extension of the gastrulating vertebrate embryo (reviewed in (Roszko et al., 2009)). However, while perturbation of PCP leads to cardiac morphological defects (Phillips et al., 2007), even severe zebrafish PCP mutants, such as MZtri mutants (where maternal and zygotic vangl2 are mutated) form a heart (data not shown). Accumulation of cells at the embryonic margin may also suggest failed regulation of cellular properties such as cell-shape changes or regulation of adhesion molecules, critical regulatory mechanisms for gastrulation (Speirs et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2009). Early patterning in the zebrafish embryo by a dorsoventral (DV) gradient of Bmp signaling has been shown regulate a gradient of Cadherin-based cell adhesion, in turn resulting in differential migratory behaviours for subsets of mesodermal populations along the DV axis (von der Hardt et al., 2007).

In the mouse, Mesp1 and Mesp2 are required for migration of cranio-cardiac mesoderm. In Mesp1/2 mutants, presumptive cardiac progenitors fail to migrate from the primitive streak and as a consequence accumulate there, resulting in heartless embryos (Kitajima et al., 2000). However, we have not observed changes in mespa/b expression in aplnrb mutant embryos (data not shown).

The non-autonomous function of aplnrb in cardiac progenitor migration was unexpected, and provides further insight into the mechanism of Aplnrb function. In general, autonomous versus non-autonomous roles of Aplnr signaling have not been closely examined. In the context of angiogenesis, the receptor is expressed in endothelial cells, suggesting a cell-autonomous mechanism of action (Cox et al., 2006; Del Toro et al., 2010), however this has not been tested formally. The temporal requirement for Aplnr signaling in early heart development is not known, however use of a hsp:apelin transgene has shown that apelin overexpression prior to (but not after) 6hpf results in a heartless phenotype (Scott et al., 2007). We therefore favour at present a non-autonomous “niche” function for Aplnr signaling. The ultimate output of this signal is likely modulation of cell-cell contacts or ECM composition that results in an alteration of cardiac progenitor migration. It is interesting to note that a role for Aplnr/Apelin signaling in embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation to cardiomyocytes was recently described (D'Aniello et al., 2009). In this study, Aplnr and Apelin were shown, via a PTX-sensitive mechanism, to act downstream of Nodal signaling to prevent neural differentiation at the expense of cardiomyocytes. It is unclear if this ES cell mechanism is fully conserved in vivo: in ES cells a Gαi/o signal is used, mediated by the Apelin ligand, which we do not observe in the context of zebrafish heart development. Further, the autonomy of Aplnr function in ES cells was not examined.

Numerous studies, both in vitro and in vivo, have described roles for Aplnr signaling in adult cardiovascular function (Ashley et al., 2005; Chandrasekaran et al., 2008; Charo et al., 2009; Szokodi et al., 2002). In these studies, a prerequisite role for Apelin, the only known Aplnr ligand (Tatemoto et al., 1998) in Aplnr function has been assumed. In vitro, PTX-sensitive signaling pathways downstream of Aplnr are activated by Apelin administration (Masri et al., 2002). Indeed, many in vivo studies of Aplnr function have relied on addition of Apelin ligand as a proxy for pathway activation. We were surprised to find that Aplnr signaling apparently acts independently of Apelin during early cardiac development in zebrafish. However, this result is consistent with aplnrb and apelin gene expression patterns, as apelin transcripts are not evident until 10hpf (Scott et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2007), by which time cardiac progenitors have largely reached their target location in the ALPM. Obviously, our negative MO results for apelin with respect to heart formation cannot alone absolutely prove that Aplnrb is acting independently of Apelin. It is interesting to note, however, that analysis of Apelin and Aplnr mutant mice has in some cases noted discrepancies in what would be expected to be identical phenotypes (Charo et al., 2009; Ishida et al., 2004; Kuba et al., 2007). Notably, murine Aplnr -/- mutants exhibited cardiac developmental defects while Apelin -/- mutants did not. This led the authors to suggest that the Aplnr may act in an Apelin-independent manner in some contexts (Charo et al., 2009). Future evaluation of endogenous Aplnr function should therefore be careful to consider not only ectopic addition of Apelin, but also loss of Aplnr function.

Interestingly, our results strongly argue for a Gαi/o-independent mechanism of Aplnr activity in the context of cardiac progenitor migration to the ALPM. While both loss of aplnrb and overexpression of PTX result in heartless embryos, this appears to be due to distinct mechanisms. Aplnrb was absolutely required in a non-autonomous fashion for heart development, whereas PTX did not show strict autonomous or non-autonomous functions. Further, embryos lacking Aplnr signaling did not contain cells in the heart-forming region of the ALPM, suggesting a failure of cells to reach this location. In contrast, inhibition of Gαi/o signaling via PTX did not affect the migration of cells to the ALPM. Instead, PTX-treated embryos had cells in the ALPM that could not initiate myocardial differentiation. An effect on cardiomyocyte development following global inhibition of Gαi/o proteins is not unexpected. Gαi/o proteins have been shown to be effectors of Hh signaling through their coupling to Smoothened (Riobo et al., 2006) and it was recently shown in zebrafish that Hh signaling functions cell-autonomously in the development of cardiomyocytes (Thomas et al., 2008). Gαi/o proteins also act downstream of Fzd1 in the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway, and are implicated in patterning of the zebrafish embryo, likely through a cell-non-autonomous mechanism (Slusarski et al., 1997). G-protein independent signaling by GPCRs has become appreciated as a critical component of many signaling events (Shenoy et al., 2006). In the absence of a G-protein mediated (and perhaps Apelin/Aplnr-mediated) signal, Aplnrb may be functioning in a number of ways. Signaling may be via recruitment of β-arrestin, and may occur following receptor internalization (Shenoy et al., 2006). Aplnrb may dimerize with other GPCRs, affecting their response to ligands, nature or strength of downstream signaling pathways (Han et al., 2009; Maurice et al., 2010; Monnier et al., 2011). Finally, signaling may occur via Aplnrb ligand(s) that remain to be discovered. Recent work suggests that the hypotensive effects of Apelin/Aplnr signaling in the vasculature may occur independently of Gαi/o-mediated cAMP inhibition (Iturrioz et al., 2010). The mechanisms through which Apelin/Aplnr signaling regulates many described aspects of development, homeostasis and disease (Barnes et al., 2010; Carpene et al., 2007; Quazi et al., 2009) therefore requires further investigation.

Due to the specific involvement of both Aplnr signaling and cBAF activity in the migration of myocardial progenitor cells to the ALPM, and subsequent differentiation into cardiomyocytes, we investigated the relationship between the two. Interestingly, our results suggest that cBAF functions downstream of Aplnr signaling, in a cell-autonomous manner, to mediate the migration of cells to the heart-field region of the developing embryo. The extracellular factor(s) activated downstream of Aplnr is yet to be determined. However, in our hands activation of signaling pathways critical for early heart development (Fgf, Nodal, Bmp, canonical Wnt, and Shh) were not sufficient to rescue the aplnra/b morphant phenotype (results not shown). The relationship between Aplnr signaling and cBAF function requires future study. However, it is tempting to speculate that the Aplnr signaling may allow for formation of an active form of a Gata5 associated with Smarcd3-containing BAF complex. As neither the effectors of Aplnr signaling in cardiac progenitor migration nor the regulators of cBAF activity have been elucidated, the link between the two is an important connection that requires further investigation.

In summary, our work shows that Aplnr signaling regulates the migration of cardiac progenitor cells from the lateral embryonic margin to the ALPM (Fig. 6D), a step essential for cardiomyocyte development. The non-autonomous nature of Aplnr signaling in this context suggests that Aplnr supports a niche that cardiac progenitors require for their proper differentiation or migration. As a key early step in cardiac progenitor development has been postulated to involve changes in migratory behaviour (Christiaen et al., 2008; Tam et al., 1997), Aplnr signals may be instructive or permissive for this event. Inducers and effectors of this pathway remain to be elucidated, and their identification will be critical to understanding the earliest events of cardiac progenitor development. Further, this will likely aid future work in the differentiation and growth of cardiomyocyte populations from various stem cell populations for cell therapy, preclinical drug screening and disease mechanism study applications.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish Strains and Embryo Maintenance

Zebrafish embryos were grown at 28°C in embryo medium following standard procedures (Westerfield, 1993). grns608 mutants, which harbour a mutation in aplnrb, as well as tp53zdf1, Tg(myl7:EGFP)twu34 and Tg(hsp:apelin)hsc1 zebrafish lines have been previously described (Berghmans et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2007).

Microinjection

MOs used to target translation of aplnra/agtrl1a (5′ – cggtgtattccggcgttggctccat – 3′), aplnrb/agtrl1b (5′ – cagagaagttgtttgtcatgtgctc – 3′), and apelin (5′ – gatcttcacattcatttctgctctc – 3′) have been previously described (Scott et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2007) and were purchased from Gene Tools (Oregon, USA). For embryos injected with aplnra/b MO, 1 ng of aplnra and 0.5 ng of aplnrb MO was injected. 8 ng of apelin MO was injected. MOs targeting splicing of gata5 (5′ – tgttaagatttttacctatactgga – 3′) and translation of gata6 (5′ – agctgttatcacccaggtccatcca – 3′) were used as previously described (Peterkin et al., 2003; Trinh et al., 2005), with 2 ng of gata5 MO and 0.5 ng of gata6 MO co-injected into one-cell stage embryos. An 800 bp fragment of the PTX coding sequence was PCR amplified from pSP64T-Ptx (Hammerschmidt and McMahon, 1998) and subcloned into pCS2+. pCS2+ mypaCterm-GRK2, encoding the C-terminal portion of GRK2 fused to C-terminal palmitoylation and myristoylation sites, was constructed by Stephane Angers (University of Toronto). pCS2+-Gata5 and Smarcd3b constructs have been previously described (Lou et al., 2011). PTX, mypaCterm-GRK2, gata5 and smarcd3b mRNA was prepared from linearized plasmids using an mMessage mMachine kit (Applied Biosystems). 100 pg of PTX or 25 pg of mypaCterm-GRK2 mRNA was injected into each one-cell stage embryo. For rescue experiments, 50 pg each of gata5 and smarcd3 b mRNA was injected into each one-cell stage embryo.

RNA In Situ Hybridization and Histology

RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) was carried out as previously described (Thisse and Thisse, 2008) using riboprobes specific for apelin, fli1, gata1, gata5, nkx2.5, myl7, spi1, and tal1. DNA fragments for all probes were amplified by RT-PCR (sequences available upon request). ISH images were taken on a Leica MZ16 microscope at a magnification of 115X. Sectioning of embryos (embedded in 4% low-melt agarose) was performed on a Leica VT1200S Vibratome with a speed of 0.7 mm/s, amplitude of 3.0 mm, and section width of 150 µM. Images were taken on a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Photoconversion

The KikGR coding sequence (purchased from MBL International, Japan) was amplified by PCR and subcloned into pCS2+. KikGR mRNA was made using the mMessage mMachine kit (Applied Biosciences) from a linearized pCS2+ KikGR template. 150 pg of KikGR mRNA was injected at the one-cell stage into wildtype embryos either with or without aplnra/b MO. Cells of the lateral embryonic margin (displaced 90° from the shield at 6hpf) were photoconverted on a Zeiss AxioImager M1by closing the fluorescence diaphragm such that only the cells of interest were visible. This region of the embryo was exposed to UV light (through the DAPI filter) for a period of one minute. Images of embryos were taken on a Zeiss AxioImager M1 microscope using either the 5X or 10X objective.

Transplantation

Transplantation was carried out as previously described (Scott et al., 2007). Donor and host embryos were injected with appropriate amounts of aplnra/b MO or PTX RNA as specified above. 10–20 cells from myl7:EGFP donor embryos were transplanted into the embryonic margin of unlabeled wildtype hosts. Hosts were scored at 48hpf for the presence of donor-derived EGFP+ cardiomyocytes in the heart. Images of embryos were taken on a Leica M205FA microscope at a magnification of 175X.

Statistics

For transplantation and photoconversion data, statistics were performed using an unpaired T-test with unequal variances.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Scott lab for insightful discussion, suggestions and technical assistance. Thanks to Angela Morley and Sasha Fernando for zebrafish care and facility maintenance. Thanks to Stephane Angers, Jason Berman and Matthias Hammerschmidt for kindly providing pCS2+ mypaC-term GRK2, tp53zdf1 fish and pSP64T-Ptx, respectively. S.P. was supported in part by Restracomp, an award from the Research Training Center at the Hospital for Sick Children. This work was supported in part by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research to I.C.S. (Funding Reference Number 86663).

References

- Ashley E. A., Powers J., Chen M., Kundu R., Finsterbach T., Caffarelli A., Deng A., Eichhorn J., Mahajan R., Agrawal R. et al. (2005). The endogenous peptide apelin potently improves cardiac contractility and reduces cardiac loading in vivo. Cardiovasc. Res. 65, 73–82 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auda-Boucher G., Bernard B., Fontaine-Perus J., Rouaud T., Mericksay M., Gardahaut M. F. (2000). Staging of the commitment of murine cardiac cell progenitors. Dev. Biol. 225, 214–225 10.1006/dbio.2000.9817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G., Japp A. G., Newby D. E. (2010). Translational promise of the apelin--APJ system. Heart 96, 1011–1016 10.1136/hrt.2009.191122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghmans S., Murphey R. D., Wienholds E., Neuberg D., Kutok J. L., Fletcher C. D., Morris J. P., Liu T. X., Schulte-Merker S., Kanki J. P. et al. (2005). tp53 mutant zebrafish develop malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 407–412 10.1073/pnas.0406252102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondue A., Blanpain C. (2010). Mesp1: a key regulator of cardiovascular lineage commitment. Circ. Res. 107, 1414–1427 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpene C., Dray C., Attane C., Valet P., Portillo M. P., Churruca I., Milagro F. I., Castan-Laurell I. (2007). Expanding role for the apelin/APJ system in physiopathology. J. Physiol. Biochem. 63, 359–373 10.1007/BF03165767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran B., Dar O., McDonagh T. (2008). The role of apelin in cardiovascular function and heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 10, 725–732 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charo D. N., Ho M., Fajardo G., Kawana M., Kundu R. K., Sheikh A. Y., Finsterbach T. P., Leeper N. J., Ernst K. V., Chen M. M. et al. (2009). Endogenous regulation of cardiovascular function by apelin-APJ. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H1904–H1913 10.1152/ajpheart.00686.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. N., Fishman M. C. (1996). Zebrafish tinman homolog demarcates the heart field and initiates myocardial differentiation. Development 122, 3809–3816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. N., Haffter P., Odenthal J., Vogelsang E., Brand M., van Eeden F. J., Furutani-Seiki M., Granato M., Hammerschmidt M., Heisenberg C. P. et al. (1996). Mutations affecting the cardiovascular system and other internal organs in zebrafish. Development 123, 293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiaen L., Davidson B., Kawashima T., Powell W., Nolla H., Vranizan K., Levine M. (2008). The transcription/migration interface in heart precursors of Ciona intestinalis. Science 320, 1349–1352 10.1126/science.1158170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codina J., Hildebrandt J., Iyengar R., Birnbaumer L., Sekura R. D., Manclark C. R. (1983). Pertussis toxin substrate, the putative Ni component of adenylyl cyclases, is an alpha beta heterodimer regulated by guanine nucleotide and magnesium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80, 4276–4280 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C. M., D'Agostino S. L., Miller M. K., Heimark R. L., Krieg P. A. (2006). Apelin, the ligand for the endothelial G-protein-coupled receptor, APJ, is a potent angiogenic factor required for normal vascular development of the frog embryo. Dev. Biol. 296, 177–189 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aniello C., Lonardo E., Iaconis S., Guardiola O., Liguoro A. M., Liguori G. L., Autiero M., Carmeliet P., Minchiotti G. (2009). G protein-coupled receptor APJ and its ligand apelin act downstream of Cripto to specify embryonic stem cells toward the cardiac lineage through extracellular signal-regulated kinase/p70S6 kinase signaling pathway. Circ. Res. 105, 231–238 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Toro R., Prahst C., Mathivet T., Siegfried G., Kaminker J. S., Larrivee B., Breant C., Duarte A., Takakura N., Fukamizu A. et al. (2010). Identification and functional analysis of endothelial tip cell-enriched genes. Blood 116, 4025–4033 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S. M., Yelon D., Conlon F. L., Kirby M. L. (2010). Myocardial lineage development. Circ. Res. 107, 1428–1444 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Martinez V., Schoenwolf G. C. (1993). Primitive-streak origin of the cardiovascular system in avian embryos. Dev. Biol. 159, 706–719 10.1006/dbio.1993.1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt M., McMahon A. P. (1998). The effect of pertussis toxin on zebrafish development: a possible role for inhibitory G-proteins in hedgehog signaling. Dev. Biol. 194, 166–171 10.1006/dbio.1997.8796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Moreira I. S., Urizar E., Weinstein H., Javitch J. A. (2009). Allosteric communication between protomers of dopamine class A GPCR dimers modulates activation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 688–695 10.1038/nchembio.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta K., Tsujii H., Omura T. (2006). Cell tracking using a photoconvertible fluorescent protein. Nat. Protoc. 1, 960–967 10.1038/nprot.2006.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzinger A., Evans T. (2007). Gata5 and Gata6 are functionally redundant in zebrafish for specification of cardiomyocytes. Dev. Biol. 312, 613–622 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. J., Tu C. T., Hsiao C. D., Hsieh F. J., Tsai H. J. (2003). Germ-line transmission of a myocardium-specific GFP transgene reveals critical regulatory elements in the cardiac myosin light chain 2 promoter of zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 228, 30–40 10.1002/dvdy.10356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki T., Garcia-Martinez V., Schoenwolf G. C. (1993). Regulative ability of the prospective cardiogenic and vasculogenic areas of the primitive streak during avian gastrulation. Dev. Dyn. 197, 57–68 10.1002/aja.1001970106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida J., Hashimoto T., Hashimoto Y., Nishiwaki S., Iguchi T., Harada S., Sugaya T., Matsuzaki H., Yamamoto R., Shiota N. et al. (2004). Regulatory roles for APJ, a seven-transmembrane receptor related to angiotensin-type 1 receptor in blood pressure in vivo. J Biol Chem 279, 26,274–26,279 10.1074/jbc.M404149200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturrioz X., Gerbier R., Leroux V., Alvear-Perez R., Maigret B., Llorens-Cortes C. (2010). By interacting with the C-terminal Phe of apelin, Phe255 and Trp259 in helix VI of the apelin receptor are critical for internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32,627–32,637 10.1074/jbc.M110.127167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai A., Shintani N., Oda M., Kakuda M., Hashimoto H., Matsuda T., Hinuma S., Baba A. (2004). Apelin is a novel angiogenic factor in retinal endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325, 395–400 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattman S. J., Huber T. L., Keller G. M. (2006). Multipotent flk-1+ cardiovascular progenitor cells give rise to the cardiomyocyte, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle lineages. Dev. Cell 11, 723–732 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan B. R., Meyer D., Yelon D. (2004). Organization of cardiac chamber progenitors in the zebrafish blastula. Development 131, 3081–3091 10.1242/dev.01185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima S., Takagi A., Inoue T., Saga Y. (2000). MesP1 and MesP2 are essential for the development of cardiac mesoderm. Development 127, 3215–3226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch W. J., Hawes B. E., Inglese J., Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (1994). Cellular expression of the carboxyl terminus of a G protein-coupled receptor kinase attenuates G beta gamma-mediated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 6193–6197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro I., Izumo S. (1993). Csx: a murine homeobox-containing gene specifically expressed in the developing heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 8145–8149 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba K., Zhang L., Imai Y., Arab S., Chen M., Maekawa Y., Leschnik M., Leibbrandt A., Makovic M., Schwaighofer J. et al. (2007). Impaired Heart Contractility in Apelin Gene Deficient Mice Associated With Aging and Pressure Overload. Circ. Res. 101, 32–42 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. K., Stainier D. Y., Weinstein B. M., Fishman M. C. (1994). Cardiovascular development in the zebrafish. II. Endocardial progenitors are sequestered within the heart field. Development 120, 3361–3366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lints T. J., Parsons L. M., Hartley L., Lyons I., Harvey R. P. (1993). Nkx-2.5: a novel murine homeobox gene expressed in early heart progenitor cells and their myogenic descendants. Development 119, 419–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Sanchez C., Garcia-Masa N., Ganan C. M., Garcia-Martinez V. (2009). Movement and commitment of primitive streak precardiac cells during cardiogenesis. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53, 1445–1455 10.1387/ijdb.072417cl [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X., Deshwar A. R., Crump J. G., Scott I. C. (2011). Smarcd3b and Gata5 promote a cardiac progenitor fate in the zebrafish embryo. Development 138, 3113–3123 10.1242/dev.064279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masri B., Lahlou H., Mazarguil H., Knibiehler B., Audigier Y. (2002). Apelin (65-77) activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases via a PTX-sensitive G protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290, 539–545 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice P., Daulat A. M., Turecek R., Ivankova-Susankova K., Zamponi F., Kamal M., Clement N., Guillaume J. L., Bettler B., Gales C. et al. (2010). Molecular organization and dynamics of the melatonin MT receptor/RGS20/G(i) protein complex reveal asymmetry of receptor dimers for RGS and G(i) coupling. EMBO J. 29, 3646–3659 10.1038/emboj.2010.236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier C., Tu H., Bourrier E., Vol C., Lamarque L., Trinquet E., Pin J. P., Rondard P. (2011). Trans-activation between 7TM domains: implication in heterodimeric GABAB receptor activation. EMBO J. 30, 32–42 10.1038/emboj.2010.270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti A., Caron L., Nakano A., Lam J. T., Bernshausen A., Chen Y., Qyang Y., Bu L., Sasaki M., Martin-Puig S. et al. (2006). Multipotent embryonic isl1+ progenitor cells lead to cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell diversification. Cell 127, 1151–1165 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden S. K., Fei D. L., Schilling N. S., Ahmed Y. F., Hwa J., Robbins D. J. (2008). G protein Galphai functions immediately downstream of Smoothened in Hedgehog signalling. Nature 456, 967–970 10.1038/nature07459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parameswaran M., Tam P. P. (1995). Regionalisation of cell fate and morphogenetic movement of the mesoderm during mouse gastrulation. Dev. Genet. 17, 16–28 10.1002/dvg.1020170104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterkin T., Gibson A., Patient R. (2003). GATA-6 maintains BMP-4 and Nkx2 expression during cardiomyocyte precursor maturation. EMBO J. 22, 4260–4273 10.1093/emboj/cdg400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips H. M., Rhee H. J., Murdoch J. N., Hildreth V., Peat J. D., Anderson R. H., Copp A. J., Chaudhry B., Henderson D. J. (2007). Disruption of Planar Cell Polarity Signaling Results in Congenital Heart Defects and Cardiomyopathy Attributable to Early Cardiomyocyte Disorganization. Circ. Res. 101, 137–145 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.142406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quazi R., Palaniswamy C., Frishman W. H. (2009). The emerging role of apelin in cardiovascular disease and health. Cardiol. Rev. 17, 283–286 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181b3fe0d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifers F., Walsh E. C., Leger S., Stainier D. Y., Brand M. (2000). Induction and differentiation of the zebrafish heart requires fibroblast growth factor 8 (fgf8/acerebellar). Development 127, 225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter J. F., Verkade H., Stainier D. Y. (2001). Bmp2b and Oep promote early myocardial differentiation through their regulation of gata5. Dev. Biol. 234, 330–338 10.1006/dbio.2001.0259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riobo N. A., Saucy B., Dilizio C., Manning D. R. (2006). Activation of heterotrimeric G proteins by Smoothened. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12,607–12,612 10.1073/pnas.0600880103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roszko I., Sawada A., Solnica-Krezel L. (2009). Regulation of convergence and extension movements during vertebrate gastrulation by the Wnt/PCP pathway. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 986–997 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga Y., Miyagawa-Tomita S., Takagi A., Kitajima S., Miyazaki J., Inoue T. (1999). MesP1 is expressed in the heart precursor cells and required for the formation of a single heart tube. Development 126, 3437–3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott I. C., Masri B., D'Amico L. A., Jin S. W., Jungblut B., Wehman A., Baier H., Audigier Y., Stainier D. Y. R. (2007). The G-Protein Coupled Receptor Agtrl1b Regulates Early Development of Myocardial Progenitors. Dev. Cell 12, 403–413 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepich D. S., Calmelet C., Kiskowski M., Solnica-Krezel L. (2005). Initiation of convergence and extension movements of lateral mesoderm during zebrafish gastrulation. Dev. Dyn. 234, 279–292 10.1002/dvdy.20507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy S. K., Drake M. T., Nelson C. D., Houtz D. A., Xiao K., Madabushi S., Reiter E., Premont R. T., Lichtarge O., Lefkowitz R. J. et al. (2006). beta-arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1261–1273 10.1074/jbc.M506576200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusarski D. C., Corces V. G., Moon R. T. (1997). Interaction of Wnt and a Frizzled homologue triggers G-protein-linked phosphatidylinositol signalling. Nature 390, 410–413 10.1038/37138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorli S. C., Le Gonidec S., Knibiehler B., Audigier Y. (2007). Apelin is a potent activator of tumour neoangiogenesis. Oncogene 26, 7692–7699 10.1038/sj.onc.1210573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speirs C. K., Jernigan K. K., Kim S. H., Cha Y. I., Lin F., Sepich D. S., DuBois R. N., Lee E., Solnica-Krezel L. (2010). Prostaglandin Gbetagamma signaling stimulates gastrulation movements by limiting cell adhesion through Snai1a stabilization. Development 137, 1327–1337 10.1242/dev.045971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stainier D. Y., Lee R. K., Fishman M. C. (1993). Cardiovascular development in the zebrafish. I. Myocardial fate map and heart tube formation. Development 119, 31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetman D., Wagstaff L., Cooper O., Weijer C., Munsterberg A. (2008). The migration of paraxial and lateral plate mesoderm cells emerging from the late primitive streak is controlled by different Wnt signals. BMC Dev. Biol. 8, 63 10.1186/1471-213X-8-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szokodi I., Tavi P., Foldes G., Voutilainen-Myllyla S., Ilves M., Tokola H., Pikkarainen S., Piuhola J., Rysa J., Toth M. et al. (2002). Apelin, the novel endogenous ligand of the orphan receptor APJ, regulates cardiac contractility. Circ. Res. 91, 434–440 10.1161/01.RES.0000033522.37861.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam P. P., Parameswaran M., Kinder S. J., Weinberger R. P. (1997). The allocation of epiblast cells to the embryonic heart and other mesodermal lineages: the role of ingression and tissue movement during gastrulation. Development 124, 1631–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatemoto K., Hosoya M., Habata Y., Fujii R., Kakegawa T., Zou M. X., Kawamata Y., Fukusumi S., Hinuma S., Kitada C. et al. (1998). Isolation and characterization of a novel endogenous peptide ligand for the human APJ receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251, 471–476 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C., Thisse B. (2008). High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat. Protoc. 3, 59–69 10.1038/nprot.2007.514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas N. A., Koudijs M., van Eeden F. J., Joyner A. L., Yelon D. (2008). Hedgehog signaling plays a cell-autonomous role in maximizing cardiac developmental potential. Development 135, 3789–3799 10.1242/dev.024083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonissen K. F., Drysdale T. A., Lints T. J., Harvey R. P., Krieg P. A. (1994). XNkx-2.5, a Xenopus gene related to Nkx-2.5 and tinman: evidence for a conserved role in cardiac development. Dev. Biol. 162, 325–328 10.1006/dbio.1994.1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh L. A., Stainier D. Y. (2004). Fibronectin regulates epithelial organization during myocardial migration in zebrafish. Dev. Cell 6, 371–382 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00063-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh L. A., Yelon D., Stainier D. Y. (2005). Hand2 regulates epithelial formation during myocardial diferentiation. Curr. Biol. 15, 441–446 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker B., Hepperle C., Kortschak D., Rainbird B., Wells S., Oates A. C., Lardelli M. (2007). Zebrafish Angiotensin II Receptor-like 1a (agtrl1a) is expressed in migrating hypoblast, vasculature, and in multiple embryonic epithelia. Gene Expr. Patterns 7, 258–265 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S., Weidinger G., Osugi T., Kohn A. D., Golob J. L., Pabon L., Reinecke H., Moon R. T., Murry C. E. (2007). Biphasic role for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiac specification in zebrafish and embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9685–9690 10.1073/pnas.0702859104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Hardt S., Bakkers J., Inbal A., Carvalho L., Solnica-Krezel L., Heisenberg C. P., Hammerschmidt M. (2007). The bmp gradient of the zebrafish gastrula guides migrating lateral cells by regulating cell-cell adhesion. Curr. Biol. 17, 475–487 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warga R. M., Kimmel C. B. (1990). Cell movements during epiboly and gastrulation in zebrafish. Development 108, 569–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. (1993). The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish Danio (Brachydanio) rerio. Oregon: University of Oregon Press [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. M., Chien K. R., Mummery C. (2008). Origins and fates of cardiovascular progenitor cells. Cell 132, 537–543 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C., Ciruna B., Solnica-Krezel L. (2009). Convergence and extension movements during vertebrate gastrulation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 89, 163–192 10.1016/S0070-2153(09)89007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Q., Wagstaff L., Yang X., Weijer C., Munsterberg A. (2008). Wnt3a-mediated chemorepulsion controls movement patterns of cardiac progenitors and requires RhoA function. Development 135, 1029–1037 10.1242/dev.015321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutzey K. E., Kirby M. L. (2002). Wherefore heart thou? Embryonic origins of cardiogenic mesoderm. Dev. Dyn. 223, 307–320 10.1002/dvdy.10068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X. X., Wilm T. P., Sepich D. S., Solnica-Krezel L. (2007). Apelin and its receptor control heart field formation during zebrafish gastrulation. Dev. Cell 12, 391–402 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou M. X., Liu H. Y., Haraguchi Y., Soda Y., Tatemoto K., Hoshino H. (2000). Apelin peptides block the entry of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). FEBS Lett. 473, 15–18 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01487-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.