Abstract

The hemea3/CuB active site of cytochrome c oxidase is responsible for cellular nitrite reduction to nitric oxide; the same center can return NO to the nitrite pool via oxidative chemistry. Here, we show that a partially reduced heme/Cu assembly reduces NO2− ion producing nitric oxide. The heme serves as the reductant while the CuII ion is also required. In turn, a µ-oxo hemeFeIII-O-CuII complex facilitates NO oxidation to nitrite; the final products are the reduced heme and CuII-nitrite complexes.

Nitrogen oxides (NOx) are components of great interest in both biological and environmental sciences. Nitric oxide (NO) is an important cellular signaling molecule and powerful vasodilator involved in many physiological and pathological processes.1 Nitrite (NO2−), is the one-electron oxidized product of endogenous NO metabolism. Recent studies indicate that nitrite plays a critical biological role, by serving as a biochemical circulating reservoir for NO, in particular under conditions of physiologic hypoxia (low O2-tensions, see also below) and ischemia. The nitrite-to-NO conversion represents an important alternative source of NO to the classical oxygen-dependent L-arginine-derived NO generation catalyzed by nitric oxide synthase (NOS).2 Subsequently, suggested conserved roles for the NO2−/NO pool in cellular processes are such as oxygen-sensing and oxygen-dependent modulation of intermediary metabolism.3 It is now considered that in order to stimulate NO signaling, nitrite reductase activity occurs widely, in differing cellular environments, and it is effected by a variety of proteins/enzymes, including hemes, those with molybdenum,4 and what draws our current interest, cytochrome c oxidases (CcO). 3,5

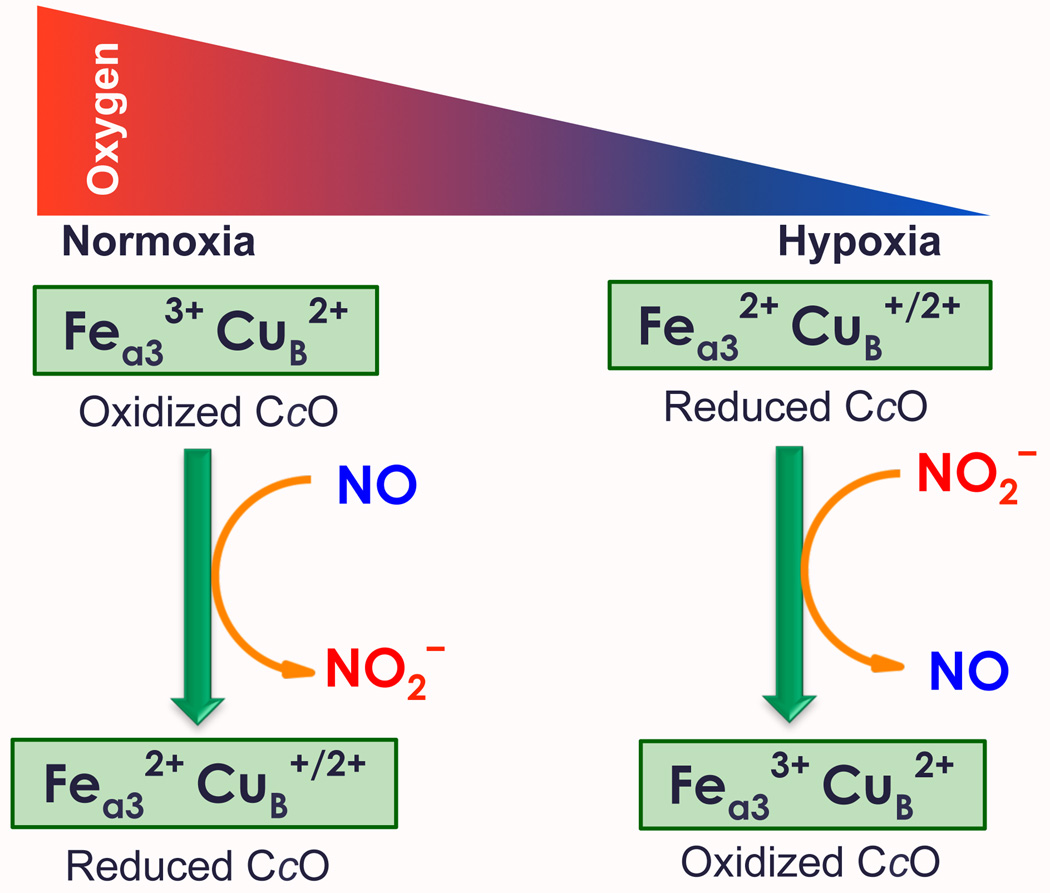

The link between nitrite/NO redox interconversion and O2-sensing is thought to occur in mitochondria at the CcO binuclear hemea3/CuB center; CcO is the terminal enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Here, molecular oxygen consumption (i.e., O2 reduction to water) is down-regulated in hypoxia by increased NO generation via CcO nitrite reductase activity, as reduced heme/Cu centers dominate when the O2 concentration is low.3a,4,6 The NO thus generated inhibits CcO activity by reversibly binding to hemea3, in place of O2, resulting in cellular O2 accumulation (Figure 1). Some of the NO produced also participates in hypoxic signaling, the up-regulation of nuclear genes needed in response to the inherent dangers of low O2 cellular concentrations.3

Figure 1.

Cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) functioning in nitrite (NO2−) and nitric oxide (NO) interconversion, as part of its role in regulation of dioxygen balance. Molecular oxygen availability influences the redox state of the CcO containing (hemea3/CuB) binuclear center.

In turn, in normoxia, high local O2 concentrations do not allow nitrite to compete as an oxidant at the CcO binuclear center; NO/O2 binding is non-competitive7 and hemea3/CuB oxidizes NO back to nitrite (Figure 1), to rejoin the storage pool. NO is thought to first attack oxidized CuB, formally giving CuI-NO+; the latter hydrolyzes to nitrite.8, 9

In this report, we describe a chemical system involving a heme/Cu assembly mediated interconversion of these important nitrogen oxides. A partially reduced/oxidized state, with reduced heme and oxidized copper ion, i.e., FeII..CuII, efficiently converts nitrite to NO. When we employ a fully oxidized FeIII…CuII heme/Cu complex, NO is readily oxidized to nitrite. The overall reactions are represented by equations 1 and 2.

| (1) |

| (2) |

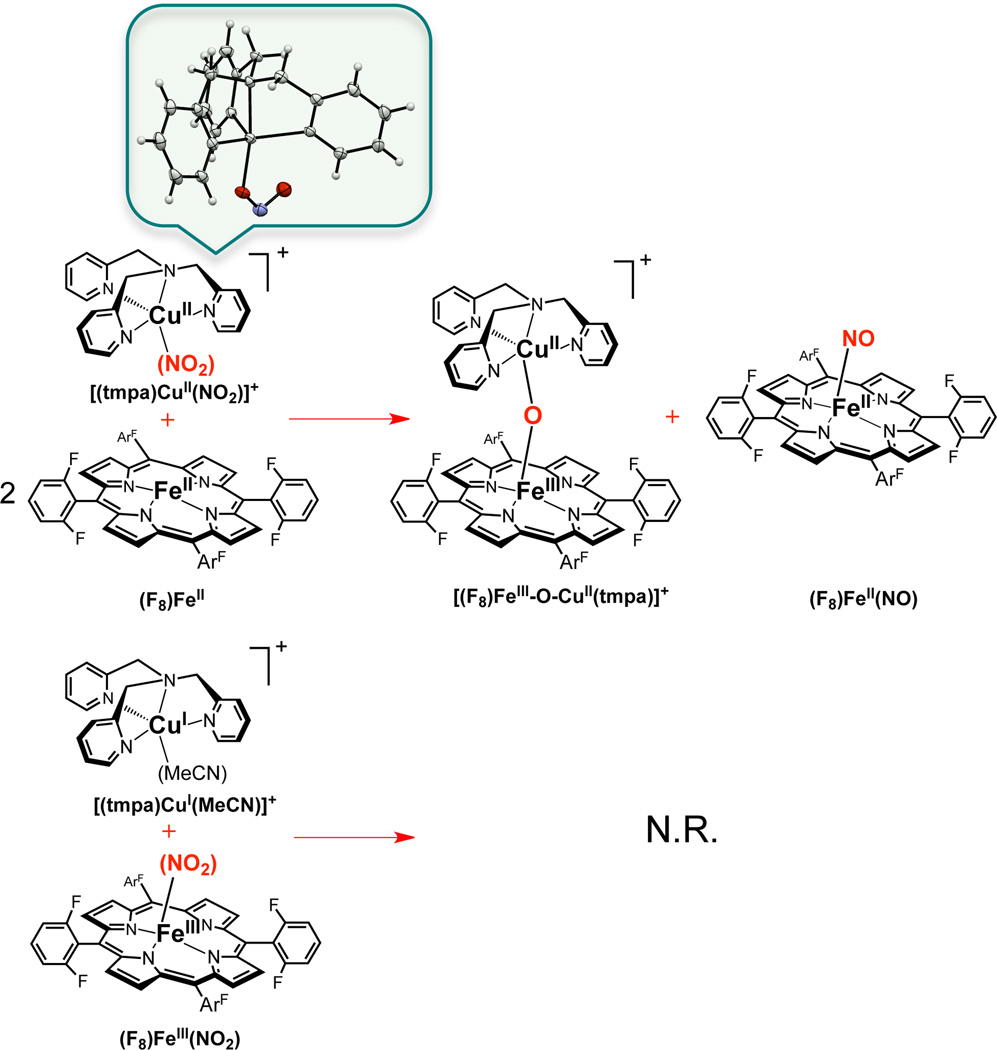

Nitrite reductase chemistry,10 here however in a heme/Cu chemical system, consists of the iron(II) complex (F8)FeII (F8 ≡ tetrakis(2,6-difluorophenyl)porphyrinate(2−))11 and a preformed copper(II)-nitrite complex [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]-[B(C6F5)4] (tmpa ≡ tris(2-pyridyl-methylamine); the latter was synthesized by adding AgNO2 to a chloride precursor [(tmpa)CuII(Cl)][B(C6F5)4] and its X-ray structure reveals an O-bound nitrito ligated Cu(II) ion (Scheme 1).12

Scheme 1.

Heme/Copper Assembly Mediated Nitrite Reduction to Nitric Oxide.

When two equiv (F8)FeII are mixed with one equiv [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]+ under a N2 atmosphere in acetone at RT, a reaction ensues and based on UV-vis, EPR and IR spectroscopies, a one-to-one mixture of the heme-nitrosyl species (F8)FeII(NO) and the µ-oxo complex [(F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)]+ are produced.12 These products are readily identified, having been previously thoroughly characterized.13 To determine whether it is the heme or the copper ion that is the reductant in this one-electron process (NO2− ––> NO), we also carried out the reaction where nitrite was added to the oxidized heme complex [(F8)FeIII]SbF6 13b (binding of nitrite to the ferric heme14 is indicated by the large UV-vis change which occurs)12 and then the reduced complex [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ 12,15 was added. In this case there was no reaction (Scheme 1), even over a period of days.12 Control experiments show that nitrite reacts only very slowly with (F8)FeII and not at all with [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+. Moreover, nitrite reductase activity is not observed for the fully reduced metal combination, nitrite plus (F8)FeII and [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+.12

These observations indicate that the heme is the reductant in this heme/Cu nitrite reductase chemistry. The need for two equiv of complex (F8)FeII is due to the well-known high affinity of NO to bind ferrous hemes.16 Nitric oxide formed first reacts very rapidly with (F8)FeII; thus, if the reaction is carried out with equimolar quantities of (F8)FeII and [(tmpa)CuII−(NO2)]+, only ½ of the iron is available to reduce nitrite, and the rest traps the NO as (F8)FeII(NO). The role of the CuII ion appears to be that a Lewis Acid interaction with nitrite, facilitating NO2− (N–O) bond cleavage, and stabilization of the resulting oxo anion via eventual formation of [(F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)]+.

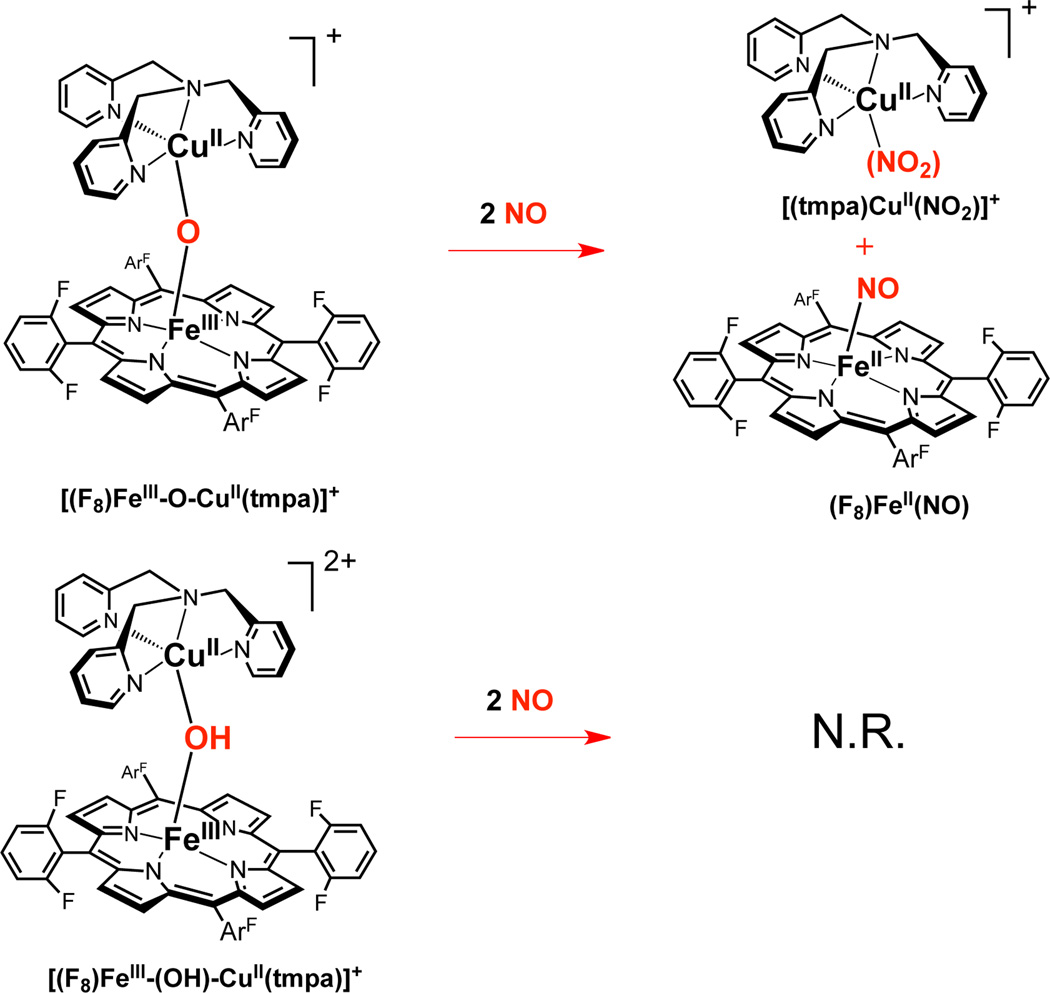

In demonstrating that heme/copper assemblies can mediate NO oxidation to nitrite, as occurs biologically in order to remove excess NO when it is not needed, and restore it into the nitrite pool (vide supra), we employed [(F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)]+. Addition of NO to this fully oxidized hetero-binuclear complex leads to rapid reaction (Scheme 2) and formation of nitrite which binds to Cu(II); the (F8)FeII which forms17 in this redox reaction is trapped by a 2nd equiv of NO to give (F8)FeII(NO). UV-vis (Figure 2) and IR (νNO = 1688 cm−1)12 spectroscopies directly indicate nitrosyl complex formation. Nitrite analysis employing capillary electrophoresis reveals production of a 95% yield of this ion.13 EPR spectroscopy confirms that a copper(II)-nitrito complex is produced (Figure 2); a sample taken from the reaction mixture is identical in all regards to that of an authentic sample of a 1:1 mixture of (F8)FeII(NO) and [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]+.

Scheme 2.

Heme/Copper Assembly Mediated Nitric Oxide Oxidation to Nitrite.

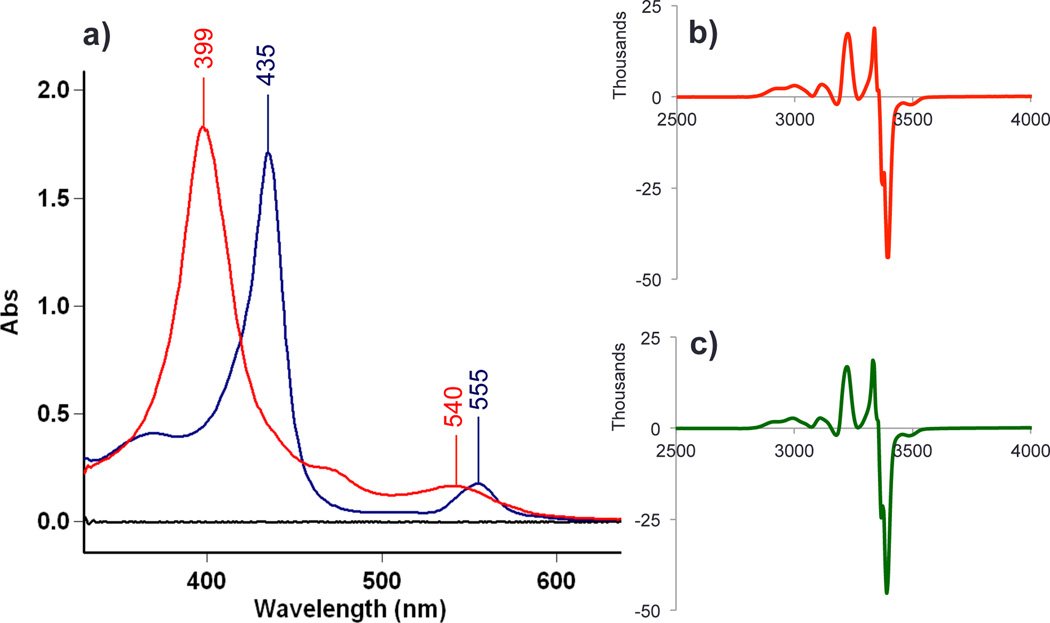

Figure 2.

a) UV-vis spectra of (F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)][B(C6F5)4] (1) ( ), (F8)FeII(NO) (

), (F8)FeII(NO) ( ) generated from 1 + NO(g) (12 µM in acetone at RT); b) EPR spectrum of the reaction products of (F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)][B(C6F5)4] and NO (

) generated from 1 + NO(g) (12 µM in acetone at RT); b) EPR spectrum of the reaction products of (F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)][B(C6F5)4] and NO ( ) and; c) EPR spectrum of an authentic sample of a 1:1 F8FeII(NO) and [(tmpa)Cu(NO2)][B(C6F5)4] mixture (

) and; c) EPR spectrum of an authentic sample of a 1:1 F8FeII(NO) and [(tmpa)Cu(NO2)][B(C6F5)4] mixture ( ). EPR spectra were recorded at 20 K (1 mM in MeTHF).

). EPR spectra were recorded at 20 K (1 mM in MeTHF).

It is important to explain why the reaction requires two mole-equiv of NO (Scheme 2). The 2nd equiv is not involved in redox chemistry, but is needed to trap free left-over (F8)FeII which is produced by the NO oxidase chemistry.

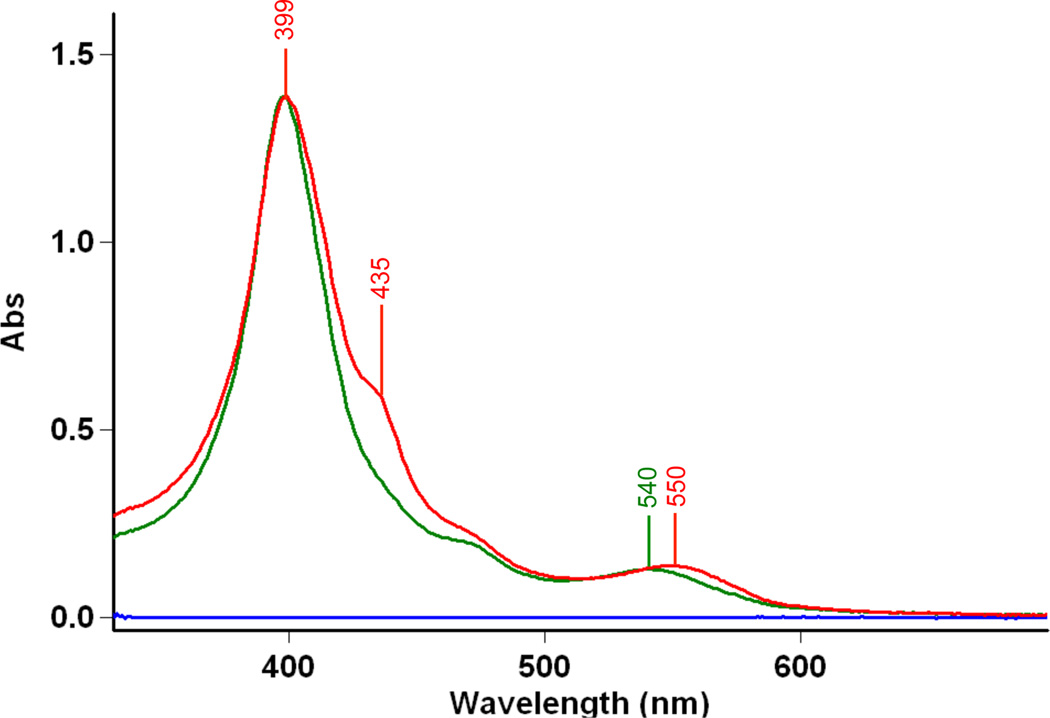

If (F8)FeII is present, it effects the reverse reaction, i.e., reduction of nitrite bound to Cu(II), giving NO, Scheme 1. This can be demonstrated as follows: When 25 mL of a 10 µM solution containing the reaction product mixture (F8)FeII(NO) and [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]+, that derived from [(F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)]+ + xs NO, (green spectrum, Figure 3), is titrated with 25 mL of a 20 µM (2 equiv) solution of (F8)FeII, the product solution (red spectrum, Figure 3) shows that ~5 µM [(F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)]+ is present, along with 10 µM (F8)FeII(NO), the spectral intensity now equivalent to that observed in the starting mixture, because of dilution. This proves that the backward reaction can and does occur, i.e., that [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]+ reacts firstly with (F8)FeII in a 1:1 stoichiometry to give NO, then trapped by the second equiv (F8)FeII.

Figure 3.

To the product solution (F8)FeII(NO) (λmax = 399 nm) plus [(tmpa)CuII(NO2)]+ ( ), derived from the NO oxidase chemistry, is added 2 equiv (F8)FeII. The resulting solution (

), derived from the NO oxidase chemistry, is added 2 equiv (F8)FeII. The resulting solution ( spectrum) reveals the presence of a 2:1 mixture of (F8)FeII(NO) (λmax = 399 nm) and [(F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)]+ (435 nm, sh). The new 2nd equiv (F8)FeII(NO) derives from nitrite reductase chemistry described by Scheme 1. See text for further explanation.

spectrum) reveals the presence of a 2:1 mixture of (F8)FeII(NO) (λmax = 399 nm) and [(F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)]+ (435 nm, sh). The new 2nd equiv (F8)FeII(NO) derives from nitrite reductase chemistry described by Scheme 1. See text for further explanation.

We also tested the µ-hydroxo complex [(F8)FeIII-(OH)-CuII(tmpa)]2+ for ‘NO oxidase’ chemistry, but upon addition of NO, there is no nitrite production (Scheme 2).12 Instead, very slow (hours) reductive nitrosylation18 occurs and all the heme present is converted to (F8)FeII(NO). It is thus clear that the µ-oxo complex ([(F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)]+ is efficient or at least special in its ability to effect a redox reaction (formally FeIII ––> FeII) which includes oxo-transfer.19

In summary, this report describes new chemistry with heme/Cu assemblies and nitrogen oxide interconversion: Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide can be readily effected with our heme/copper chemistry. The reduced heme is the source of the one-electron required. The presence of CuII ion, as Lewis Acid, is crucial. While nitrite reduction to NO is well known to occur via heme proteins such as Hb and Mb,20 bacteria/fungal heme cd1 21 or copper nitrite reductases22 and certain copper(I) complexes,22a,23 the transformation with heme/Cu synthetic complexes until now seems to not have been examined. We have shown here that both heme and Cu are required, at least in our system. It is notable that the heme is the reductant, based on the observed products; however cyclic voltammetric determination of redox potentials for separate (F8)Fe (−0.20 V vs Fc+/Fc)12 and Cu(tmpa) (−0.42 V vs Fc+/Fc)12 complexes indicate the latter is a better reductant. For CcO, the opposite appears to be the case, as the hemea3 has a lower redox potential than does CuB.24

On the other hand, the heme is also the redox entity as [(F8)FeIII-O-CuII(tmpa)] effects NO-oxidation to nitrite by oxo-transfer (vide supra);19 (F8)FeIII becomes reduced. The closely related species [(F8)FeIII-(OH)-CuII(tmpa)]+ and/or heme-only complexes do not enable this reaction. Yet, as already mentioned, it is the CuB in CcO which is thought to oxidize NO,9 and it is well known that NO can react with CuII complexes,25 affording nitrite. This may imply that in CcO it is a particular coordination environment, a specific structural and/or redox state, that is required to mediate NO oxidase chemistry.

Further investigations will include our probing of the mechanisms of the reactions described in this report. For nitrite reduction, critical mechanistic components will certainly include heme reductive capability and the nitrite-Cu binding mode, e.g., O-, vs O,O’- vs N-bound. As our heme and Cu centers have switched redox capabilities compared to CcO, we will wish to change the heme or the Cu-ligand so as to make the Cu center a better oxidant than the heme. For our heme/Cu NO oxidation chemistry, we are uncertain about which metal is the real oxidant.18 Further investigations are required. “The devil is in the details.”

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM060353 to K.D.K.). We also thank Dr. Richard C. Himes for help in synthesizing [(tmpa)CuII(Cl)][B(C6F5)4].

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Synthetic and analytical details, UV-vis, IR and EPR spectra, cyclic voltammetry results, capillary electrophoresis results, X-ray structural details and cif files. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Ignarro LJ. Nitric Oxide as a Communication Signal in Vascular and Neuronal Cells. In: Lancaster J, editor. Nitric Oxide: Principles and Actions. New York: Academic Press Inc.; 1996. p. 111. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schopfer MP, Wang J, Karlin KD. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:6267–6282. doi: 10.1021/ic100033y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Samouilov A, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;357:1–7. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dezfulian C, Raat N, Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;75:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Castello PR, David PS, McClure T, Crook Z, Poyton RO. Cell Metabolism. 2006;3:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Feelisch M, Fernandez BO, Bryan NS, Garcia-Saura MF, Bauer S, Whitlock DR, Ford PC, Janero DR, Rodriguez J, Ashrafian H. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:33927–33934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806654200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Faassen EE, Bahrami S, Feelisch M, Hogg N, Kelm M, Kim-Shapiro DB, Kozlov AV, Li H, Lundberg JO, Mason R, Nohl H, Rassaf T, Samouilov A, Slama-Schwok A, Shiva S, Vanin AF, Weitzberg E, Zweier J, Gladwin MT. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2009;29:683–741. doi: 10.1002/med.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Sarti P, Giuffre A, Barone MC, Forte E, Mastronicola D, Brunori M. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2003;34:509–520. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gupta KJ, Igamberdiev AU. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:537–543. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sarti P, Forte E, Mastronicola D, Giuffrè A, Arese M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1817:610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Curtis E, Hsu LL, Noguchi AC, Geary L, Shiva S. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2012;17:951–961. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Toledo JC, Augusto O. Chem. Res. Toxic. 2012;25:975–989. doi: 10.1021/tx300042g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poyton RO, Castello PR, Ball KA, Woo DK, Pan N. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1177:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mason MG, Nicholls P, Wilson MT, Cooper CE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:708–713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506562103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Antunes F, Boveris A, Cadenas E. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2007;9:1569–1580. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Torres J, Sharpe MA, Rosquist A, Cooper CE, Wilson MT. FEBS Letters. 2000;475:263–266. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01682-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) The multicopper enzyme ceruloplasmin has also been shown to effect NO oxidase (NO –> NO2–) chemistry. Shiva S, Wang X, Ringwood LA, Xu X, Yuditskaya S, Annavajjhala V, Miyajima H, Hogg N, Harris ZL, Gladwin MT. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:486–493. doi: 10.1038/nchembio813. Paradis M, Gagné J, Mateescu MA, Paquin J. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2010;49:2019–2027. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.030.

- 10.(a) Castiglione N, Rinaldo S, Giardina G, Stelitano V, Cutruzzola F. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2012;17:684–716. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Merkle AC, Lehnert N. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:3355–3368. doi: 10.1039/c1dt11049g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Kopf MA, Neuhold YM, Zuberbühler AD, Karlin KD. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:3093–3102. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghiladi RA, Kretzer RM, Guzei I, Rheingold AL, Neuhold YM, Hatwell KR, Zuberbühler AD, Karlin KD. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:5754–5767. doi: 10.1021/ic0105866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.See Supporting Information.

- 13.(a) Wang J, Schopfer MP, Sarjeant AAN, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:450–451. doi: 10.1021/ja8084324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang J, Schopfer MP, Puiu SC, Sarjeant AAN, Karlin KD. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:1404–1419. doi: 10.1021/ic901431r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Karlin KD, Nanthakumar A, Fox S, Murthy NN, Ravi N, Huynh BH, Orosz RD, Day EP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:4753–4763. [Google Scholar]; (d) Fox S, Nanthakumar A, Wikström M, Karlin KD, Blackburn NJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Finnegan MG, Lappin AG, Scheidt WR. Inorg. Chem. 1990;29:181–185. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wyllie GRA, Scheidt WR. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1067–1089. doi: 10.1021/cr000080p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucas HR, Meyer GJ, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12927–12940. doi: 10.1021/ja104107q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper CE. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1411:290–309. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.By analogy to what has in the past been suggested for the enzyme reaction,8b nitric oxide attacks at the cupric center, formally leading to CuI-NO+, with oxo transfer to the latter, along with electron transfer from CuI to FeIII, giving the CuII-nitrito complex, and FeII (which is then trapped by a second NO molecule). Separately, we can demonstrate that with the present ligand-complexes, [(tmpa)CuI(MeCN)]+ and [(F8)FeIII]SbF6, the CuI-to-FeIII electron-transfer readily occurs in acetone, see Supporting Information.

- 18.(a) Ford PC. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:6226–6239. doi: 10.1021/ic902073z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fernandez BO, Lorkovic IM, Ford PC. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:2–4. doi: 10.1021/ic020519r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Man W-L, WY Lam W, Ng S-M, YK Tsang W, Lau T-C. Chem.-Eur. J. 2012;18:138–144. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Doyle RP. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2012;389:1–2. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gladwin MT, Grubina R, Doyle MP. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:157–167. doi: 10.1021/ar800089j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shiva S, Huang Z, Grubina R, Sun JH, Ringwood LA, MacArthur PH, Xu XL, Murphy E, Darley-Usmar VM, Gladwin MT. Circulation Research. 2007;100:654–661. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260171.52224.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yi J, Heinecke J, Tan H, Ford PC, Richter-Addo GB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18119–18128. doi: 10.1021/ja904726q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Averill BA. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2951–2964. doi: 10.1021/cr950056p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zumft WG. Microbiol. Molec. Biol. Revs. 1997;61:533–616. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.533-616.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lehnert N, Berto TC, Galinato MGI, Goodrich LE. The Role of Heme-Nitrosyls in the Biosynthesis, Transport, Sensing, and Detoxification of Nitric Oxide (NO) in Biological Systems: Enzymes and Model Complexes. In: Kadish KM, Smith K, Guilard R, editors. The Handbook of Porphyrin Science. Vol. 14. Singapore: World Scientific; 2011. pp. 1–247. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Wasser IM, de Vries S, Moënne-Loccoz P, Schröder I, Karlin KD. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1201–1234. doi: 10.1021/cr0006627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Merkle AC, McQuarters AB, Lehnert N. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:8047–8059. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30464c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Hsu SCN, Chang YL, Chuang WJ, Chen HY, Lin IJ, Chiang MY, Kao CL, Chen HY. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:9297–9308. doi: 10.1021/ic300932a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kumar M, Dixon NA, Merkle AC, Zeller M, Lehnert N, Papish ET. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:7004–7006. doi: 10.1021/ic300160c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nicholls P, Wrigglesworth JM. Annals New York Acad. Sci. 1988;550:59–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb35323.x. Moskovitz J. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1703:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.09.003. Gorbikova EA, Vuorilehto K, Wikstrom M, Verkhovsky MI. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5641–5649. doi: 10.1021/bi060257v. Belevich I, Bloch DA, Belevich N, Wikstrom M, Verkhovsky MI. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:2685–2690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608794104. (e) CcO metal center redox potentials are highly dependent on the redox states of the other metal-cofactors as well as the pH/protonation-state.

- 25.(a) Tran D, Skelton BW, White AH, Laverman LE, Ford PC. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:2505–2511. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kalita A, Kumar P, Deka RC, Mondal B. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:1251–1253. doi: 10.1039/c1cc16316g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.