Abstract

Introduction:

Clavicle fractures accounting for 3 to 5% of all adult fractures are usually treated non-operatively. There is an increasing trend toward their surgical fixation. The aim of our study was to investigate the outcome following titanium elastic stable intramedullary nailing (ESIN) for midshaft non-comminuted clavicle fractures with >20 mm shortening/displacement.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 38 patients, which met inclusion criteria, were reviewed retrospectively. There were 32 males and six females. The mean age was 27.6 years. The patients were assessed for clinical/radiological union and by Oxford Shoulder and QuickDASH scores. 71% patients required open reduction.

Results:

100% union was achieved at average of 11.3 weeks. The average follow-up was 12 months. The average Oxford Shoulder and QuickDASH scores were 45.6 and 6.7, respectively. 47% patients had nail removal. One patient had lateral nail protrusion while other required its medial trimming.

Conclusion:

In our hands, ESIN is safe and minimally invasive with good patient satisfaction, cosmetic appearance, and overall outcome.

Keywords: Clavicle fracture, elastic stable intramedullary nailing, midshaft fractures

INTRODUCTION

The midshaft clavicle fractures account for 3 to 5% of all injuries and 70 to 80% of all clavicle fractures.[1,2] In young adults, these fractures are usually related to sports or vehicle accidents, whereas in children and elderly, they are usually related to falls.[1,2] In general, clavicle fractures are treated conservatively and have a good outcome. In 1960, Neer reported a non-union rate of 0.1% with conservative treatment[3] and Rowe corroborated these findings in 1968 and showed a non-union rate of 0.8% in conservatively managed patients.[4] Since then, however, other authors have failed to demonstrate similar good results with conservative treatment.[5,6] This may be due to the fact that the initial series included children and adolescents and their enormous potential for bone healing may have skewed the results, and that patient-based scoring systems were not used in the initial series to record the outcome.[7] Hill et al. showed that displacement of more than 20 mm resulted in 15% non-union and 18% of the patients had thoracic outlet syndrome following union.[5] McKee et al. noted reduced patient satisfaction due to asymmetry and cosmesis following malunion in patients with more than 20 mm shortening.[6] Hence, more recently, there has been a trend toward surgical fixation. Surgery has been indicated for completely displaced fractures, potential skin perforation, shortening of clavicle by more than 20 mm, neurovascular injury, and floating injury.[8] The gold standard for the surgical treatment has been open reduction and plate fixation through a large incision.[8] Other surgical options include intramedullary pinning with Kirschner wire, Rush pins, Knolwes pin, Steinman pin, Haige pin, ESIN (elastic stable intramedullary nailing), and external fixation.[9]

Intramedullary fixation for clavicular fractures was first described by Peroni in 1950.[10] A systematic review showed relative risk reduction of 72% and 57% for non-union when using intramedullary fixation and plate fixation, respectively, when compared with non-operative treatment of midshaft clavicle fractures.[11] Intramedullary devices behave as internal splints that maintain alignment without rigid fixation. The use of an intramedullary device carries advantages of a smaller incision, less soft tissue dissection, load sharing fixation with relative stability that encourages copious callus formation.[12] The titanium ESIN has been successfully used in fixation of pediatric long bone fractures. One advantage of the titanium ESIN is that it can block itself in the bone and provide a three-point fixation within the S-shaped clavicle.[8,13] However, some studies have shown a relatively high complication rate and technical difficulties with intramedullary nailing.[7,8]

The aim of this study was to investigate the union rate and complication rate of our patients with displaced midshaft clavicle fractures treated with titanium ESIN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data collection was approved by the local hospital's clinical governance department and results were presented locally before publication.

A retrospective review of a cohort of 38 patients who presented to our institute between January 2007 and June 2009 with displaced midshaft clavicle fractures and treated with titanium ESIN was carried out. The patients were retrospectively identified from theatre log and hospital clinical coding. Data were obtained from the patients’ case notes, radiographs, and clinic letters and in some cases telephonic consultations.

The inclusion criteria for this study were diaphyseal midshaft, non-comminuted clavicle fractures with more than 20 mm shortening/displacement in any view. Exclusion criteria were patients with proximal or distal fractures, floating shoulder, brachial plexus injury, and comminuted fractures.

There were 32 males and six females in this study. The mean age was 27.6 years (range, 14 to 57 years). The patients were operated by different surgeons in the department. All surgeons used ESIN in patients meeting the inclusion criteria.

All the patients were reviewed postoperatively in the clinic at 2, 6, 12 weeks and 6 months or until the fracture had healed clinically and radiologically. All the patients were brought back to the clinic in May-June 2009 to assess their function and outcome following clavicle fracture fixation. All the patients were assessed for clinical and radiological union and radiographs were taken at each clinic visit. We defined radiological union as visible bridging callus or absent fracture line. The clinical union was described as no bony tenderness on clinical examination. All the patients had Oxford Shoulder score and QuickDASH score, which were done at the time of their final follow-up during May-June 2009 by one of the authors and in patients who were unable to attend clinic, the scores were filled following telephonic consultations. There are no clavicle trauma scores and hence shoulder outcome scores were used. The Oxford Shoulder score, which is a questionnaire-based subjective assessment of the patients’ pain and impairment of activities of daily living, has shown to correlate well with the Constant Score and SF 36 assessment.[14] The QuickDASH is a shortened version of the DASH outcome score and uses 11 items instead of the 30 items in the full questionnaire to measure physical function and symptoms in patients with any or multiple musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb.[15]

Surgical technique

After administration of anesthesia, the patient was placed in beach chair position with injured extremity prepared and draped from the midline to the upper arm. Care was taken to make sure that the sternoclavicular joint was accessible for the entry point. Preoperatively, the shoulder region was screened using image intensifier to confirm this access.

A vertical skin incision was made just lateral to the sternoclavicular joint. The subcutaneous fat was incised along with platysma. The pectoral fascia was divided in line with the skin incision followed by careful elevation of the underlying musculature from the clavicle. The entry point was then made using the awl and appropriate sized titanium ESIN was inserted (The size of the nail was measured using this formula = 0.4 × canal diameter in mm). Attempt was made to close reduce the fracture. If the fracture could not be reduced by closed means, then a separate vertical incision was used at the fracture site to aid fracture reduction. Vertical incision was used as it was parallel to Langer's lines and minimized the risk of damage to supraclavicular nerves to avoid dysesthesia of skin and scar neuromas. At that time, the nail was used to create a path in the lateral end of the clavicle for subsequent easy access. The nail was then passed from the medial side and across the reduced fracture into the lateral end of clavicle. All the patients were put in a shoulder sling postoperatively and followed same rehabilitation regime of early gentle mobilization when pain allows, with no overhead abduction for first six weeks. The shoulder sling was discarded at 2 weeks and active-assisted exercises were started, but the patients were advised not to lift any heavy object for 6 weeks. At that time, passive and strengthening exercises were started.

RESULTS

A total of 38 patients met the inclusion criteria of diaphyseal midshaft, non-comminuted clavicle fractures with more than 20 mm shortening/displacement. Of these 38 patients, 22 patients had a fall on outstretched hand, seven had a fall from bicycle, two had a fall from height, three had a fall onto the point of shoulder, and four had road traffic accident. The average follow up was 12 months (Range, 6-24 weeks).

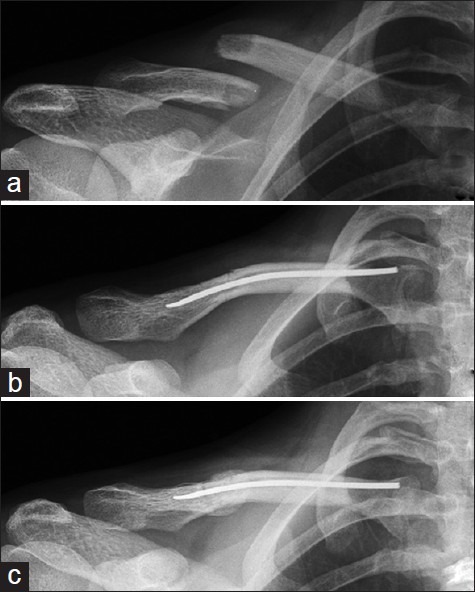

All the patients achieved clinical and radiological union at a mean of 11.3 weeks (Range, 6-20 weeks). Eleven of the 38 patients had closed nailing while 27 patients (71%) required open reduction of their fracture. The average size of the titanium flexible nail used was 2 mm (range, 1.5 -3 mm) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a) Preoperative radiograph of midshaft clavicle fracture with more than 20 mm of shortening, (b) Immediate postoperative radiograph, and (c) Radiograph at 12 weeks showing healing callus at the fracture site

The patients were followed up postoperatively and oxford shoulder score and QuickDASH scores were calculated 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and at the last follow-up. There was no statistical difference between the functional scores and the range of movement when the scores were compared at 3, 6 months and the last follow-up using Wilcoxon signed rank test (P = 0.47). The average Oxford Shoulder score was 45.6 (range, 37-48). The average QuickDASH score was 6.7 (range, 0-13.6) at the last follow-up. Three patients were interviewed telephonically as they were unable to attend the clinic for the final follow-up.

Eighteen of 38 patients had removal of the implant for symptomatic medial irritation, 7-9 months after the initial operation and after their fracture had clinically and radiologically healed. One patient required trimming of medial end of nail and one patient had lateral protrusion of the nail which was subsequently removed.

There were no major complications in our series with no cases of infections, scar neuromas, non-unions or perforation of the posterior cortex.

DISCUSSION

Plate osteosynthesis,[16,17] external fixation,[18] and intramedullary fixation[9,13,19–21] have all been described for surgical treatment of clavicle fractures. Plate osteosynthesis is still considered the standard method for the surgical treatment of clavicle shaft fractures. The advantage of this technique is good reduction with compression and rigid fixation. However, complications after plate osteosynthesis are fairly common. In a multicenter prospective randomized trial, plate osteosynthesis had better functional outcome than non-operative treatment of displaced clavicle fractures with decreased rate of non-union and symptomatic malunion.[16] Severe complications occur in 10% of the patients and include deep infection, non-union, implant failure, and fracture after implant removal. Lesser complications include superficial infection, keloid scar, dysesthesia in the region of scar, as well as implant loosening with loss of reduction.[22]

Schuind et al. in 1988 reported results of 20 patients treated with Hoffmann external fixation with no non-union and return to full range of movements of the shoulder. However, there was no objective measurement of patient satisfaction.[18]

Intramedullary stabilization is an established alternative fixation method. Intramedullary implants are optimal from biomechanical point of view as the tension side of clavicle changes with respect to rotation of arm and direction of loading.[7,13] The potential benefits of this technique include smaller incision, minimal periosteal stripping, and load sharing device properties.[12] Its relative stability allows copious callus formation during the healing process. The frequent complication includes skin irritation from the prominent medial end of the nail and this frequently leads to either trimming of the nail or its premature removal.[22] Multifragmentary fracture can lead to telescoping of the nail with shortening of the clavicle. The comminuted fractures were excluded because we believe that this fixation system cannot maintain length of the clavicle in these situations. Smekal et al. hence do not recommend use of ESIN in comminuted fractures with severe shortening.[22] Duan et al. in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials demonstrated similar functional outcome when comparing plating with intramedullary fixation.[1] They, however, showed higher symptomatic hardware-related problems with plating.[1] Zolowodzki et al. in a systematic review of 2144 cases found non-union rate of 1.6% with intramedullary fixation as compared with 2.5% with plate fixation.[11]

The intramedullary fixation provides an alternative and less invasive way of surgically treating clavicle fractures. The use of titanium elastic nails in the treatment of midshaft clavicle fractures was first described by Jubel et al.[23] In a retrospective analysis between titanium elastic nails and reconstruction plates, Chen et al. showed a significantly shorter time to union with the TEN group with no significant difference in non-union or malunion rate between TEN and plating. They showed faster functional recovery with greater patient satisfaction with cosmesis and overall outcome in the TEN group.[24] Smekal et al. showed, in a randomized control trail between intramedullary nailing and non-operative treatment, better DASH and Constant scores and 100% union rate with intramedullary nailing.[7] Liu et al. found no significant difference between functional outcome and non-union rate following plate fixation and intramedullary fixation (titanium elastic nails) of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures.[21]

Frigg et al. in their study expressed concerns about the increased complication rate.[8] In one of our patients, the nail was left slightly proud and required trimming later on. The other patient with lateral protrusion (without any involvement of the acromioclavicular joint) had minimal discomfort from it and this nail was removed once the fracture had healed. Migration of intramedullary implant has been reported in a number of studies.[13,21,22] Smekal et al. reported that 23% of their patients had medial nail protrusion and 89% of the patients required implant removal.[7] 47% of our patients had the implant removed, most of them for symptomatic medial irritation. Smekal et al. reported rate of closed vs open fracture reduction when using elastic flexible intramedullary nailing of 64:36.[25] In our study, 27 cases of 38 (71%) required open reduction, which was done through a small vertical incision at the fracture site with a minimally invasive approach. We do not consider open reduction of the fracture as unsatisfactory as despite its high rate, in our series, we achieved 100% union.

In our series, the procedure was performed by various surgeons using a standardized surgical technique as detailed earlier. Despite this, we achieved good functional and cosmetic outcome in diaphyseal midshaft, non-comminuted clavicle fractures with more than 20 mm shortening/displacement with titanium ESIN with no major complications.

This is a relatively small retrospective series of patients treated in a district general hospital with a mean follow-up of 1 year. Another drawback is the short follow-up but all fractures had united within that time period. All the patients were reviewed in the clinics of the two senior authors (LK, BV) at their last follow-up by one of the co-authors (RR) and hence the clinical examination may have been biased. However, functional outcome was measured using objective patient-based scoring systems. These scores were done at least six months after the trauma with an average follow-up of one year.

In conclusion, the intramedullary fixation of midshaft clavicle fractures is a safe minimally invasive technique in indicated cases and in our hands it provides good functional outcome and cosmetic results.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duan X, Zhong G, Cen S, Huang F, Xiang Z. Plating versus intramedullary pin or conservative treatment for midshaft fracture of clavicle: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:1008–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffer G, Faymonville C, Skouras E, Andermahr J, Jubel A. Midclavicular fracture: not just a trivial injury: Current treatment options. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:711–7. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neer CS., 2nd Nonunion of the clavicle. J Am Med Assoc. 1960;172:1006–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020100014003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowe CR. An atlas of anatomy and treatment of midclavicular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;58:29–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill JM, McGuire MH, Crosby LA. Closed treatment of displaced middle-third fractures of the clavicle gives poor results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:537–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b4.7529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKee MD, Pedersen EM, Jones C, Stephen DJ, Kreder HJ, Schemitsch EH. Deficits following nonoperative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:35–40. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smekal V, Irenberger A, Struve P, Wambacher M, Krappinger D, Kralinger FS. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing versus nonoperative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures-a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:106–12. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318190cf88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frigg A, Rillmann P, Perren T, Gerber M, Ryf C. Intramedullary nailing of clavicular midshaft fractures with the titanium elastic nail: Problems and complications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:352–9. doi: 10.1177/0363546508328103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalil A. Intramedullary screw fixation for midshaft fractures of the clavicle. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1421–4. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0724-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peroni L. Medullary osteosynthesis in the treatment of clavicle fractures. Arch Ortop. 1950;63:398–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zlowodzki M, Zelle BA, Cole PA, Jeray K, McKee MD. Evidence-Based Orthopaedic Trauma Working G. Treatment of acute midshaft clavicle fractures: Systematic review of 2144 fractures: on behalf of the Evidence-Based Orthopaedic Trauma Working Group. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:504–7. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000172287.44278.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millett PJ, Hurst JM, Horan MP, Hawkins RJ. Complications of clavicle fractures treated with intramedullary fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller M, Rangger C, Striepens N, Burger C. Minimally invasive intramedullary nailing of midshaft clavicular fractures using titanium elastic nails. J Trauma. 2008;64:1528–34. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180d0a8bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson J, Hill G, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. The benefits of using patient-based methods of assessment.Medium-term results of an observational study of shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:877–82. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b6.11316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beaton DE, Wright JG, Katz JN. Upper Extremity Collaborative G. Development of the QuickDASH: Comparison of three itemreduction approaches. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1038–46. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma S. Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1–10. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mullaji AB, Jupiter JB. Low-contact dynamic compression plating of the clavicle. Injury. 1994;25:41–5. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(94)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuind F, Pay-Pay E, Andrianne Y, Donkerwolcke M, Rasquin C, Burny F. External fixation of the clavicle for fracture or non-union in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:692–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferran NA, Hodgson P, Vannet N, Williams R, Evans RO. Locked intramedullary fixation vs plating for displaced and shortened mid-shaft clavicle fractures: A randomized clinical trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:783–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleweno CP, Jawa A, Wells JH, O’Brien TG, Higgins LD, Harris MB. Midshaft clavicular fractures: Comparison of intramedullary pin and plate fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:1114–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu HH, Chang CH, Chia WT, Chen CH, Tarng YW, Wong CY. Comparison of plates versus intramedullary nails for fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. J Trauma. 2010;69:E82–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e03d81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smekal V, Irenberger A, Attal RE, Oberladstaetter J, Krappinger D, Kralinger F. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing is best for mid-shaft clavicular fractures without comminution: Results in 60 patients. Injury. 2011;42:324–9. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jubel A, Andemahr J, Bergmann H, Prokop A, Rehm KE. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing of midclavicular fractures in athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:480–3. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.6.480. discussion 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YF, Wei HF, Zhang C, Zeng BF, Zhang CQ, Xue JF. Retrospective comparison of titanium elastic nail (TEN) and reconstruction plate repair of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smekal V, Oberladstaetter J, Struve P, Krappinger D. Shaft fractures of the clavicle: Current concepts. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:807–15. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]