Abstract

The synthesis of a 4-dibenzocyclooctynol (DIBO) functionalized polyethylene glycol (PEG) and fabrication of hydrogels via strain-promoted, metal-free, azide-alkyne cycloaddition is reported. The resulting hydrogel materials provide a versatile alternative in which to encapsulate cells that are sensitive to photochemical or chemical crosslinking mechanisms.

Keywords: hydrogel, click chemistry, human mesenchymal stem cell, cycloaddition

Polymeric hydrogels are used widely in a number of regenerative medicine applications1-3. Hydrogels are ideal materials for implantation because they generally introduce low levels of foreign matter into the host and afford high levels of metabolite and biomolecule transport4. Injectable hydrogels that form in situ hold additional promising as they are able to adapt to complicated defect sites relative to preformed hydrogels5. The crosslinking mechanisms in hydrogels can be either chemical or physical6-16. Both have advantages and disadvantages4,12,17. The onset of gel formation in covalently crosslinked hydrogels is typically dependent on chemical or photochemical processes to initiate network formation from monomeric precursors. Chemicals methods include various click reactions,18 thiolene additions,7 metal-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloadditions,6,19 Michael additions20 and Diels-Alder reactions14. However, the use of radical initiating systems, ultraviolet (UV) light, and the presence of residual metal catalysts, organic solvents, and the incomplete conversion of the functional groups may lead to biocompatibility problems in sensitive cell types. Because many chemical crosslinkers are toxic and result in noninjectable gels, physical hydrogels are preferred for many biomedical applications. However, the assembly of polymers into physical hydrogels for cell encapsulation typically requires the use of an external trigger including a change in pH, temperature, or ionic concentration to induce gelation4,16,21-24. The experimental demands for each of these gelation and functionalization strategies places distinct constraints on the utility and versatility of the respective hydrogel and make direct clinical translation very difficult.

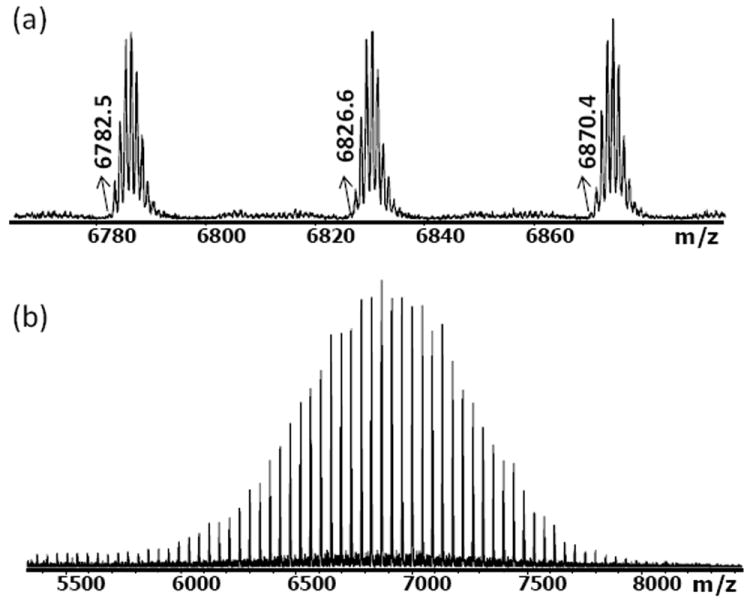

Metal free, strain-promoted azide-alkyne “click” cycloaddition reactions have been applied to cell imaging25-27 as well as hydrogels systems due to its highly efficient conversion, orthogonality, and bio-friendly characteristics.9,11,13 In this work, we describe the fabrication of a covalently crosslinked hydrogel via a strain-promoted cycloaddition reaction between 4-dibenzocyclooctynol (DIBO) functionalized poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and a 3-arm glycerol exytholate triazide. The DIBO-functionalized PEG was synthesized using a 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate activated 4-dibenzocyclooctynol and poly(ethylene gyclol) bis amine. 1H NMR (SI) and MALDI-TOF (Figure 1) results demonstrate the complete conversion of the amine group to dibenzocyclooctynol. Concentration control is critical to achieving complete conversion.

Figure 1.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of DIBO-PEG (cationized with NaTFA); monoisotopic mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) are marked in the upper spectrum. The measured m/z values agree with the desired structure.

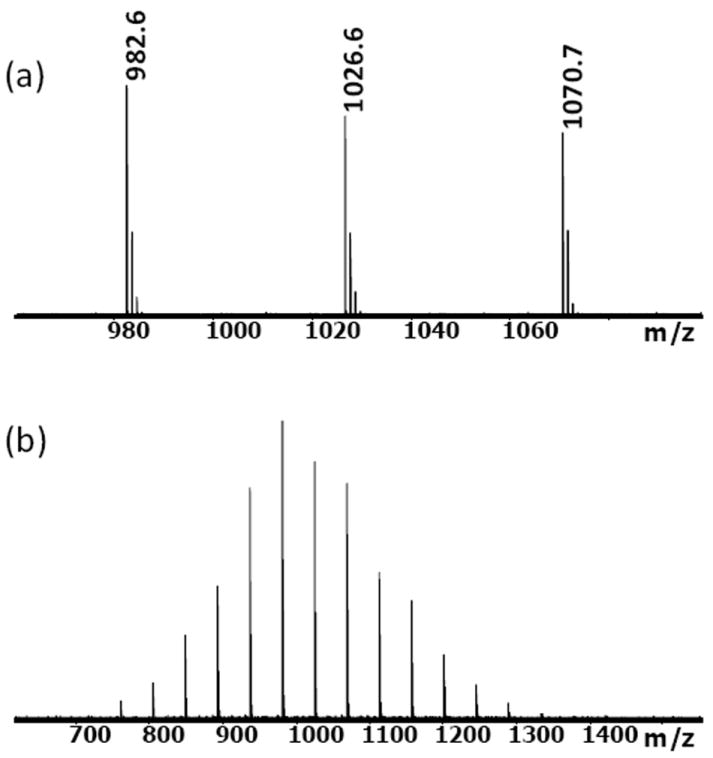

Glycerol exytholate triazide was synthesized using glycerol exytholate as the starting material. The hydroxyl groups were derivatized with methane sulfonyl chloride and further substituted using sodium azide in a two-step process. The desired product was purified by column chromatography and substantiated with 1H NMR (SI) and MALDI-TOF (Figure 2). Purified mat mechanical properties. To demonstrate the gelation of the two precursors in aqueous solution, a stoichiometric mixture of DIBO-functionalized PEG was dissolved in 50 uL ultrapure water, based on the calculation of 1:1 molar ratio for the DIBO group and azide group, 1.1 mg glycerol exytholate triazide is dissolved in 50 uL ultrapure water and these two solutions were mixed. Within 5 minutes, the solution gelled when agitated gently (Scheme 1). FTIR of the freeze-dried hydrogels confirms the disappearance of the azide groups (SI).

Figure 2.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of glycerol exytholate triazide (cationized with NaTFA); monoisotopic mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) are marked in the upper spectrum. The measured m/z values agree with the desired structure.

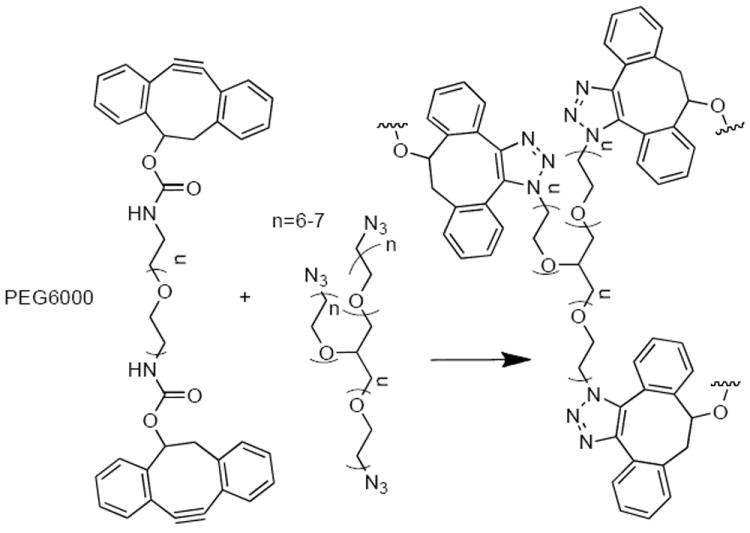

SCHEME 1.

DIBO-PEG and glycerol exytholate triazide form hydrogel networks when mixed in situ. The rate of network formation can be influenced by the rate and amplitude of strain.

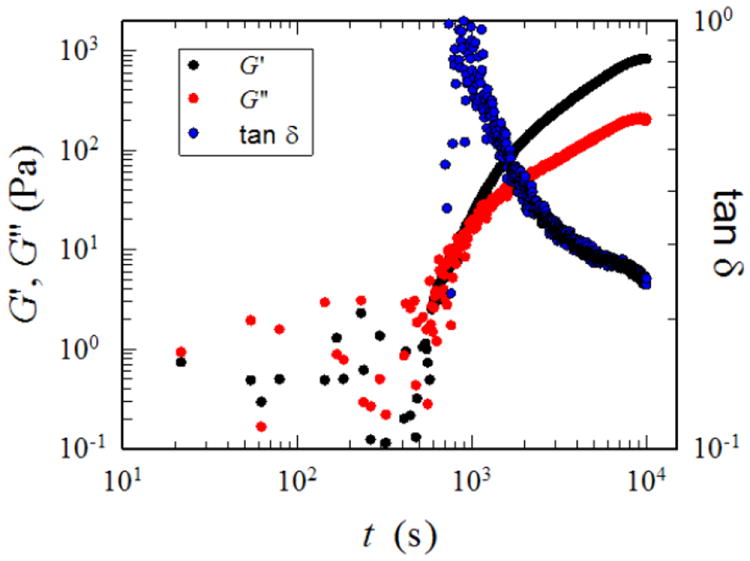

To assess whether the gel is suitable for injectable gel applications, an oscillatory shear rheology experiment was performed to study the gelation kinetics under applied mechanical forces (Figure 3). Measurements were made at 24 °C with a TA Instruments ARES-G2 rheometer equipped with 8 mm parallel plates and using a frequency of 10 rad/s (1.6 Hz) and a strain amplitude of 10%. To maintain hydration of the hydrogel sample during the experiment, the lower plate fixture included a solvent trap filled with an aqueous solution of DIBO-PEG and glycerol exytholate triazide (1:1). The large scatter in the data at times less than 600 s is a consequence of the very low viscosity of the solution before sufficient crosslinking was achieved. As a consequence, the torque values are too low to obtain reliable readings from the force transducer. However, after 600 s the torque magnitude was sufficiently high, and both G’ (the elastic part of the complex modulus, G*) and G” (the viscous component of G*) increased exponentially with time.

Figure 3.

Modulus-time dependence of hydrogels during the process of oscillation shear

At the beginning of the experiment, the solution is a viscous liquid and it is expected that G” > G’. The crossover of G’ and G” near t~1000 represents the gel point, where the crosslinking reaction has proceeded sufficiently in that the material transforms from a viscous liquid to a viscoelastic solid28. After about 2.5 h, the dynamic moduli reached equilibrium values, indicating that the crosslinking reaction was complete. The gel was fully hydrated throughout the experiment and at the end of the reaction the gel contained 96.1 % water and the plateau modulus, GN’ was ~0.8 kPa. This corresponds to a crosslink density of 8.6 mol/m3, which was calculated using the classical theory of rubber elasticity. The loss factor tan δ (G”/G’) decreased from a value of ~1, which is typical of a viscous liquid to a value of ~0.25 at the end of the reaction, which is consistent with the formation of a viscoelastic solid (tan δ is zero for an elastic solid). This reaction was also shown to be strain sensitive.

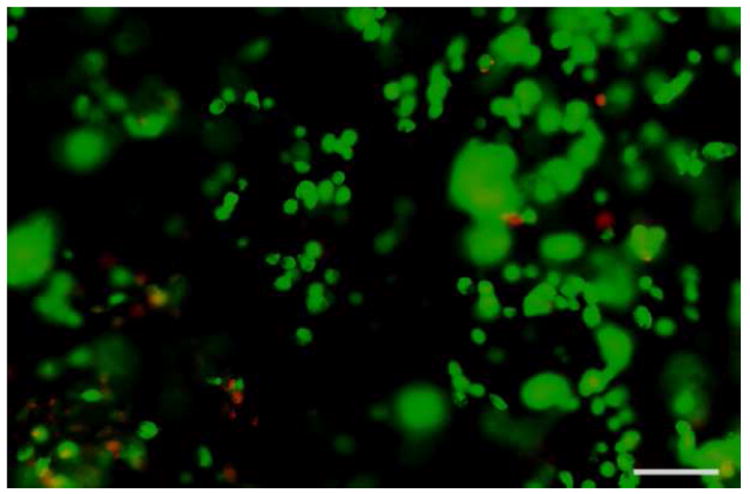

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were used to test the influence of the hydrogel crosslinking on cell viability (Figure 4). hMSCs (passage 5, 500,000 cells, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) were suspended in 25 μL of 20 wt% DIBO-PEG in 〈-MEM basal Media (Lonza). 25 μL of 2.56 wt% glycerol exytholate triazide in 〈-MEM basal Media was added to the cell suspension. The samples were mixed via gentle pipetting and placed in a mold to solidify. After 5 min, the hydrogels were transferred by spatula to a 12-well plate and cultured in 〈-MEM basal Media for 24 h in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. A live dead assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was performed. 1.5 μL of 1 mg/mL Calcein AM and 0.1 μL of 2 mM ethidium homodimer-1 was added per mL of culture media and the samples were incubated for 10 minutes. The samples were then washed with media and viewed on a 1×81x microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). The encapsulation of cells and presence of media additives did not affect the gelation process. The dominant green fluorescence from live cells in the live/dead cell staining after 24 h of culture demonstrates the excellent biocompatibility of these hydrogels (>95%). Tri-arm molecules not converted to the azide do not gel as expected and hMSCs mixed with the individual components do not exhibit toxicity (data not shown) under identical concentration conditions.

Figure 4.

A Live-Dead assay was used to assess the viability (>95%) of human mesenchymal stem cells that were crosslinked in situ and cultured in hydrogels for 24 h. Live cells are stained green and dead cells are stained red. The scale bar is 50 μm.

In conclusion, we have made a covalently crosslinked hydrogel that is versatile and biocompatible based on a metal free, strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition process. These results demonstrate an effective strategy to encapsulate cells within hydrogels where gelation is based on the cumulative effects of specific molecular-recognition interactions between strained cyclocotyne units and azide terminated PEG chains. The potential variability in the molecular mass of the respective components, number of branch units and compatibility with both hMSCs and cell media provides versatility in applications where syringe injectable materials or in situ formation of hydrogels are necessary.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation (RAW, CBET-1066517) and the National Institute of Health (MLB, P41 EB0063536).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The details about the synthesis of DIBO, DIBO-functionalized PEG, and the rheology experiments can be found in the supporting information. “This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.”

References

- 1.Drury JL, Mooney DJ. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4337–4351. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer R, Tirrell DA. Nature. 2004;428:487–492. doi: 10.1038/nature02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee KY, Mooney DJ. Chem Rev. 2001;101:1869–1879. doi: 10.1021/cr000108x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aizawa Y, Owen SC, Shoichet MS. Prog Polym Sci. 2012;37:645–658. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin R, Teixeira LSM, Krouwels A, Dijkstra PJ, van Blitterswijk CA, Karperien M, Feijen J. Acta Biomaterialia. 2010;6:1968–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nimmo CM, Shoichet MS. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2011;22:2199–2209. doi: 10.1021/bc200281k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salinas CN, Anseth KS. Macromolecules. 2008;41:6019–6026. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pritchard CD, O’Shea TM, Siegwart DM, Calo E, Anderson DG, Reynolds FM, Thomas JA, Slotkin Jr, Woodard EJ, Langer R. Biomaterials. 2011;32:587–597. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeForest CA, Polizzotti BD, Anseth KS. Nature Materials. 2009;8:659–664. doi: 10.1038/nmat2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeForest CA, Sims EA, Anseth KS. Chem Mater. 2010;22:4783–4790. doi: 10.1021/cm101391y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeForest CA, Anseth KS. Nature Chemistry. 2011;3:925–931. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hennink WE, van Nostrum CF. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2002;54:13–36. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J, Fillon TM, Prifti F, Song J. Chem Asian J. 2011;6:2730–2737. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan H, Rubin JP, Marra KG. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 2011;32:905–911. doi: 10.1002/marc.201100125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z-C, Xu X-D, Chen C-S, Yun L, Song J-C, Zhang X-Z, Zhuo R-X. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2010;2:1009–1018. doi: 10.1021/am900712e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi N, Zhang L, Chae B-S, Palla CS, Furst EM, Kiick KL. J Amer Chem Soc. 2007;129:3040. doi: 10.1021/ja0680358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aguado BA, Mulyasasmita W, Su J, Lampe KJ, Heilshorn SC. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2012;18:806–815. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iha RK, Wooley KL, Nystrom AM, Burke DJ, Kade MJ, Hawker CJ. Chem Rev. 2009;109:5620–5686. doi: 10.1021/cr900138t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Dijk M, van Nostrum CF, Hennink WE, Rijkers DTS, Liskamp RMJ. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:1608–1614. doi: 10.1021/bm1002637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bencherif SA, Washburn NR, Matyjaszewski K. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:2499–2507. doi: 10.1021/bm9004639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim IL, Mauck RL, Burdick JA. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8771–8782. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niece KL, Czeisler C, Sahni V, Tysseling-Mattiace V, Pashuck ET, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4501–4509. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pochan DJ, Schneider JP, Kretsinger J, Ozbas B, Rajagopal K, Haines L. J Amer Chem Soc. 2003;125:11802–11803. doi: 10.1021/ja0353154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seal BL, Panitch A. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1572–1582. doi: 10.1021/bm0342032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ning X, Guo J, Wolfert MA, Boons G-J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:2253–2255. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang PV, Prescher JA, Sletten EM, Baskin JM, Miller IA, Agard NJ, Lo A, Bertozzi CR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911116107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laughlin ST, Bertozzi CR. ACS Chemical Biology. 2009;4 doi: 10.1021/cb900254y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winter HH, Chambon F. J Rheology. 1986;30:367–382. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.