Abstract

TGF-β is a profibrotic growth factor in CKD, but its role in modulating the kidney’s response to AKI is not well understood. The proximal tubule epithelial cell, which is the main cellular target of AKI, expresses high levels of both TGF-β and its receptors. To determine how TGF-β signaling in this tubular segment affects the response to AKI, we selectively deleted the TGF-β type II receptor in the proximal tubules of mice. This deletion attenuated renal impairment and reduced tubular apoptosis in mercuric chloride–induced injury. In vitro, deficiency of the TGF-β type II receptor protected proximal tubule epithelial cells from hydrogen peroxide–induced apoptosis, which was mediated in part by Smad-dependent signaling. Taken together, these results suggest that TGF-β signaling in the proximal tubule has a detrimental effect on the response to AKI as a result of its proapoptotic effects.

AKI, which is most commonly caused by ischemia and nephrotoxins, dramatically increases morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients. The proximal tubule epithelial cell is a key target of AKI because of its high metabolic demands and unique vascular supply. After injury, proximal tubules undergo a loss of polarity, redistribution of integrins and junctional proteins, impaired adhesion, and, if severe, apoptosis or necrosis. Surviving epithelial cells de-differentiate, migrate over the denuded basement membrane, proliferate, and re-differentiate as part of the repair process. Growth factors modulate the proximal tubule’s response to AKI and facilitate the repair process.1–4 TGF-β is a growth factor that affects many cellular processes involved in injury and repair, but its role in AKI remains unclear.

Three mammalian TGF-β ligands (TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3) bind to the TGF-β type II receptor (TβRII), a serine/threonine kinase, leading to phosphorylation of the TGF-β type I receptor and recruitment of intracellular signaling proteins Smad2 and 3.5,6 In canonical TGF-β signaling, Smads2/3 complex with Smad4, accumulate in the nucleus, and modulate DNA transcription. However, many noncanonical signaling proteins, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), can mediate TGF-β signaling by Smad-dependent or -independent mechanisms.7,8 The complexity of TGF-β signaling may account for its pleiotropic effects, which vary depending on the target cell type and microenvironment.

TGF-β signaling has been shown to alter numerous cellular processes in vitro that may be beneficial or detrimental to the tubular response to AKI. TGF-β stimulates epithelial de-differentiation; thus, it may facilitate proximal tubule repair by accelerating de-differentiation of surviving epithelial cells, an important initial step in repair.9,10 TGF-β may also promote repair by increasing epithelial cell migration11 and upregulating integrin β1 expression, which increases cell/matrix adhesion.12 However, TGF-β can also increase proximal tubule apoptosis,13,14 which might play an important pathologic role in ischemic, septic, and toxin-induced forms of AKI.15 Furthermore, TGF-β may impair tubular recovery as it inhibits proximal tubule proliferation and retards re-differentiation in vitro.16

Similarly, in vivo studies have had conflicting results regarding TGF-β’s role in AKI. TGF-β was shown to be protective in AKI because TGF-β1–deficient mice had worsened tubular injury after ischemia/reperfusion17 and volatile anesthetics improved the response to ischemia/reperfusion by a TGF-β–dependent mechanism.18,19 In contrast to these studies, the use of a neutralizing pan–TGF-β antibody did not significantly alter the acute response to ischemia/reperfusion,20 and TGF-β signaling was shown to have detrimental effects on the response to AKI because a TGF-β type I receptor inhibitor (ALK5) accelerated recovery and Smad3−/− mice had greater preservation of renal function and less histologic injury after ischemia/reperfusion injury.16,21 With such varied conclusions, TGF-β’s role in AKI remains unclear. Furthermore, these in vivo studies used chemical inhibitors or genetic techniques to systemically inhibit TGF-β activity, an approach that does not elucidate the role of TGF-β signaling specifically in the proximal tubule.

To define how TGF-β signaling in the proximal tubule affects the response to AKI, we deleted TβRII in the proximal tubule of mice using γ-glutamyl transferase-Cre (γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox) and induced injury using mercuric chloride (HgCl2). The γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had attenuated injury that was associated with reduced tubular apoptosis compared with wild-type littermates. Furthermore, proximal tubule epithelial cells lacking TβRII in vitro were resistant to apoptosis from oxidative and nonoxidative stressors. Thus, our data suggest that attenuating TGF-β signaling in proximal tubules protects against AKI by decreasing tubular apoptosis.

Results

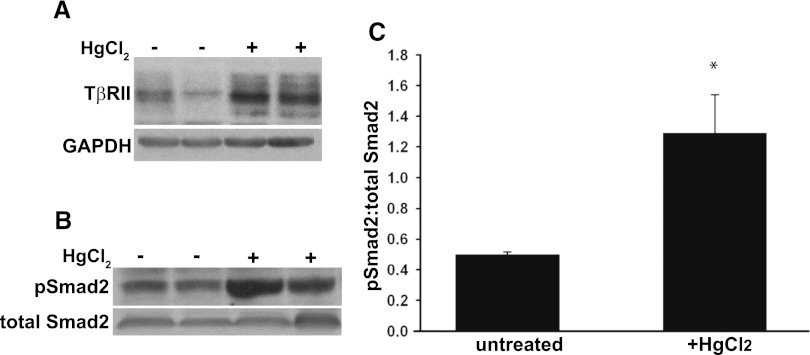

HgCl2 Increased TGF-β Signaling in Renal Cortices

We initially defined whether TGF-β signaling was increased in the HgCl2 model of AKI, which is a well established injury model that targets the proximal tubule by augmenting oxidative stress, a common mechanism of injury in clinical AKI.2,22–24 Wild-type mice had a significant increase in TβRII expression in renal cortices 3 days after HgCl2 administration (Figure 1A); at 7 days, expression declined to levels of untreated mice (data not shown). Consistent with this, Smad2 phosphorylation was increased in renal cortical lysates 1 day after HgCl2 administration (Figure 1, B and C). These data suggest that TGF-β plays a role in mediating the renal response to injury.

Figure 1.

HgCl2 stimulated TGF-β signaling in renal cortices. (A) Renal cortices were dissected from wild-type FVB mice that were injected with HgCl2 3 days earlier or were untreated. The tissue lysates were immunoblotted for TβRII expression. (B) Tissue lysates of renal cortices isolated 1 day after HgCl2 were immunoblotted for pSmad2 and total Smad2. (C) Bands from six mice (three treated, three untreated) were quantified by densitometry and reported as means ± SEMs. *P<0.05. GADPH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

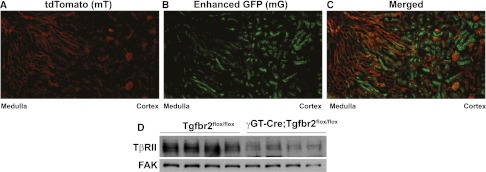

Deleting TβRII in Proximal Tubules Attenuated HgCl2-Induced Injury

To determine how TGF-β signaling in the proximal tubule affects this AKI model, we generated mice lacking TβRII specifically in the proximal tubule by crossing the Tgfbr2flox/flox mouse with one containing γGT-Cre (expressed in the proximal tubules at P10).25 We defined the location of Cre activity by intercrossing the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox and mT/mG reporter mice, which have ubiquitous expression of the membrane-bound fluorescent red tdTomato (mT) that is turned off and replaced by enhanced GFP (mG) in cells where Cre is active.26 The mT/mG γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had green fluorescence restricted to cortical tubules, consistent with the distribution of proximal tubules (Figure 2, A–C). We confirmed reduced TβRII expression in conditional knockout mice by immunoblots on renal cortices (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Deletion of TβRII in the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice. The mT/mG reporter mouse was crossed with our γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice, demonstrating membrane-bound red fluorescence (mT) in all cells except those where Cre is active and green fluorescence (mG) replaces mT (A and B). (C) The red (580–610 nm) and green (510–540 nm) wavelengths are merged, showing that Cre is primarily expressed in tubules in the cortex and corticomedullary renal tissue. (D) Cortical lysates of adult Tgfbr2flox/flox and γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice were immunoblotted for TβRII expression with focal adhesion kinase (FAK) used as loading control.

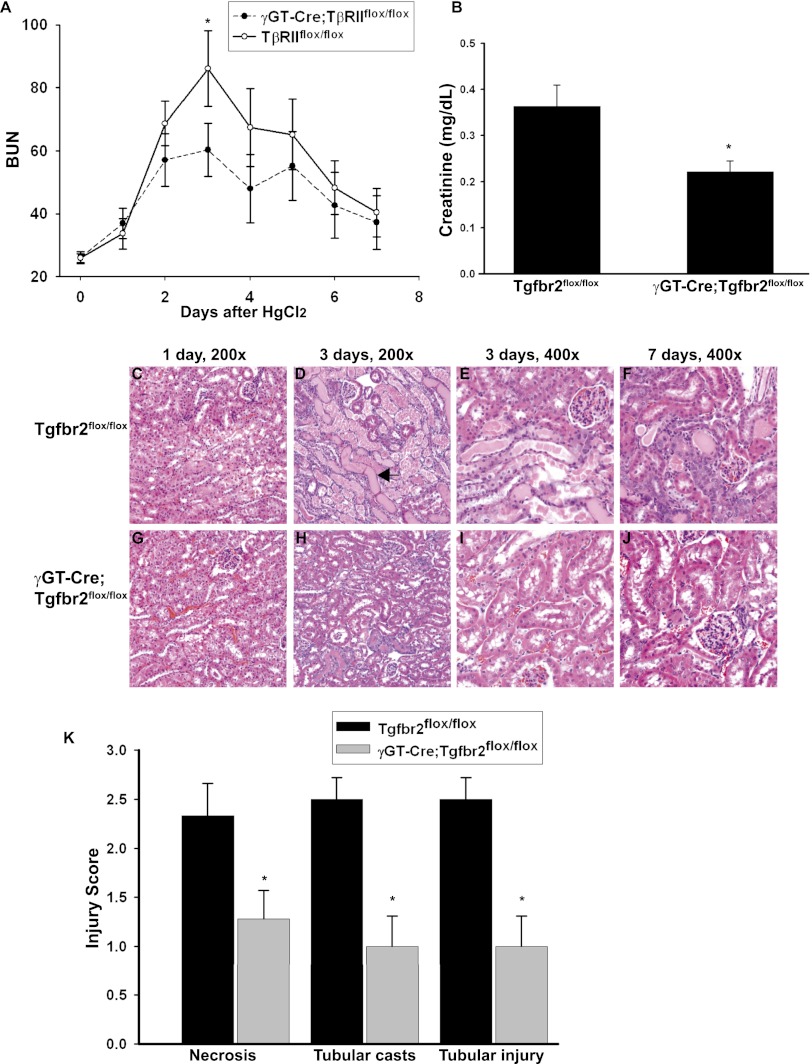

When renal injury was induced by HgCl2 (30 μmol/kg), the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had less functional impairment as measured by BUN and creatinine compared with Tgfbr2flox/flox littermates. Although both genotypes reached their peak BUN level 3 days after injury, levels were significantly lower in the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice than the Tgfbr2flox/flox mice (BUN, 60 versus 86 mg/dl; P=0.025) (Figure 3A). The BUN levels declined in both genotypes between days 4 and 7, and similar levels were reached at day 7. A significant difference in plasma creatinine levels (measured by HPLC) was also observed 3 days after injury (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice were protected from HgCl2-induced injury. (A) Plasma BUN levels (mg/dl) were measured at the time of injury and daily thereafter until euthanasia at day 7. Means are shown ± SEMs from 14 Tgfbr2flox/flox and 12 γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice. *P<0.05. (B) Plasma creatinine 3 days after HgCl2 injection was measured by HPLC on six Tgfbr2flox/flox and five γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice. Means are shown ± SEMs. *P<0.05. (C–J) Tissue from mice at 1, 3, and 7 days after treatment with HgCl2 was stained with hematoxylin and eosin. There was minimal epithelial injury 1 day after HgCl2, but at 3 days, there was significantly more cast formation (black arrow in D) and tubular necrosis in the Tgfbr2flox/flox than in the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice. Both genotypes had resolving epithelial injury at 7 days, but fewer residual tubular casts were present in the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice. (K) Injury was scored at 3 days, as discussed in the Concise Methods section. The values represent the means of six Tgfbr2flox/flox and seven γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice. Means are shown ± SEMs. *P<0.05.

Consistent with our functional data, γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice sustained less morphologic injury after treatment with HgCl2. Epithelial injury was evident 1 day after injury (Figure 3, C and G), but the difference in response to HgCl2 between γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox and Tgfbr2flox/flox mice was most pronounced 3 days after injury (Figure 3, D and H). The γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had less epithelial flattening, tubular necrosis, and cast formation (Figure 3, E and I). At 7 days after HgCl2, both groups of mice had some resolution of epithelial injury, but γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had fewer residual tubular casts (Figure 3, F and J). Injury scoring at day 3 (see Concise Methods section) showed that the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had significantly less necrosis 1.28±0.29 SE versus 2.33±0.33 SE, P=0.037; cast formation 1±0.31 SEM versus 2.5±0.22 SEM, P<0.01; and tubular injury 1±0.31 SEM versus 2.5±0.22 SEM, P<0.01 than the Tgfbr2flox/flox mice (Figure 3K).

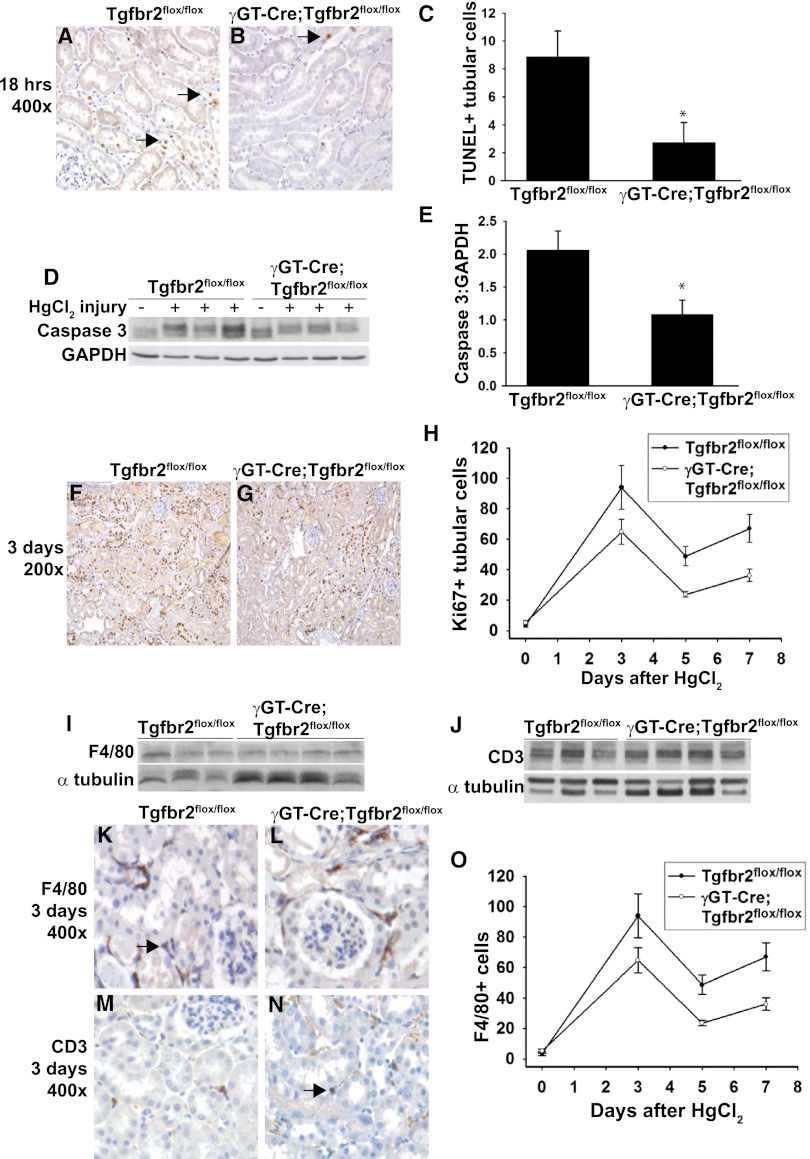

Tubular Apoptosis Is Decreased in γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox Mice

To investigate why the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had attenuated injury after HgCl2, tubular apoptosis, which TGF-β signaling promotes in vitro, was examined.13,14 We found significantly fewer terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick-end labeling (TUNEL)–positive tubular cells in the cortex of γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice at 18 hours after HgCl2 (Figure 4, A–C), and no TUNEL-positive cells in uninjured mice (data not shown). Cortical tissue immunoblots also showed significantly decreased cleaved caspase 3 expression in the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox compared with Tgfbr2flox/flox mice (Figure 4, D and E). These findings suggest that deleting TβRII in proximal tubules protects against apoptosis after HgCl2.

Figure 4.

γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had less tubular apoptosis after HgCl2. (A and B) TUNEL staining was performed at 18 hours after injury with apoptotic nuclei staining brown (arrows). (C) TUNEL-positive tubular cells from 10 hpf per mouse were counted in a blinded fashion and reported as means using five mice per genotype ± SEMs. *P<0.05. (D) Cortical kidney lysates 18 hours after HgCl2 injections were immunoblotted for cleaved caspase 3 expression using glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a loading control. Three representative mice per genotype are shown. (E) Bands were quantified by densitometry expressed as cleaved caspase 3:GAPDH means from five Tgfbr2flox/flox and six γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice ± SEMs. *P<0.05. (F–H) Ki-67 staining was performed on five mice per genotype at 0, 3, 5, and 7 days after HgCl2 treatment. (F and G) Representative staining at 3 days is shown. (H) Ki-67+ tubular cells were counted in 10 hpf per mouse at the different time points and expressed as means ± SEMs. (I and J) Cortical tissue lysates from three wild-type and four γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice at 3 days after HgCl2 injection were immunoblotted for F4/80 and CD3 to detect macrophages and T cells, respectively. Representative staining of F4/80 (K and L) and CD3 (M and N) at 3 days is shown with positively staining cells in brown (arrows). F4/80 staining was performed on four mice per genotype at days 0, 3, and 7, and F4/80+ cells were counted in 10 hpf per mouse and shown as means ± SEMs (O).

Because TGF-β signaling can inhibit proximal tubule cell proliferation,16 we assessed whether the attenuated injury in γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice was due to enhanced epithelial cell proliferation. Quantification of Ki-67–positive tubular cells at days 0, 3, 5, and 7 after injury revealed that γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had less, not more, proliferation (Figure 4, F–H). Therefore, the improved response of γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice to HgCl2-induced injury is not due to augmented tubular proliferation.

Because inflammation, which can be modulated by TGF-β signaling, plays an important pathophysiologic role in AKI, we assessed whether the improved response to HgCl2 by γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice was due to alterations in inflammatory cell infiltration. No differences were found in macrophage or T cell infiltration between the genotypes, as indicated by immunoblots of F4/80 and CD3, respectively (Figure 4, I and J). Quantification of F4/80+ cells at 0, 3, and 7 days revealed a dramatic increase in macrophage infiltration but no difference between genotypes at 3 days after injury (39±7 versus 36±3 cells/high-powered field [hpf]) and a trend toward increased macrophages in the Tgfbr2flox/flox mice at 7 days (75±10 versus 56±5 cells/hpf) (Figure 4, K, L, and O). The number of CD3+ cells was not significantly elevated at 3 days in Tgfbr2flox/flox mice compared with baseline (2.7±0.3/hpf versus 2.4±0.45/hpf), and no differences were noted between genotypes (2.7±0.3 versus 3.6±0.3) (Figure 4, M and N), quantification of data not shown). These results suggest that the reduction in HgCl2-induced injury observed in γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice was not due to changes in tubular proliferation or inflammation but was, in part, due to reduced tubular apoptosis.

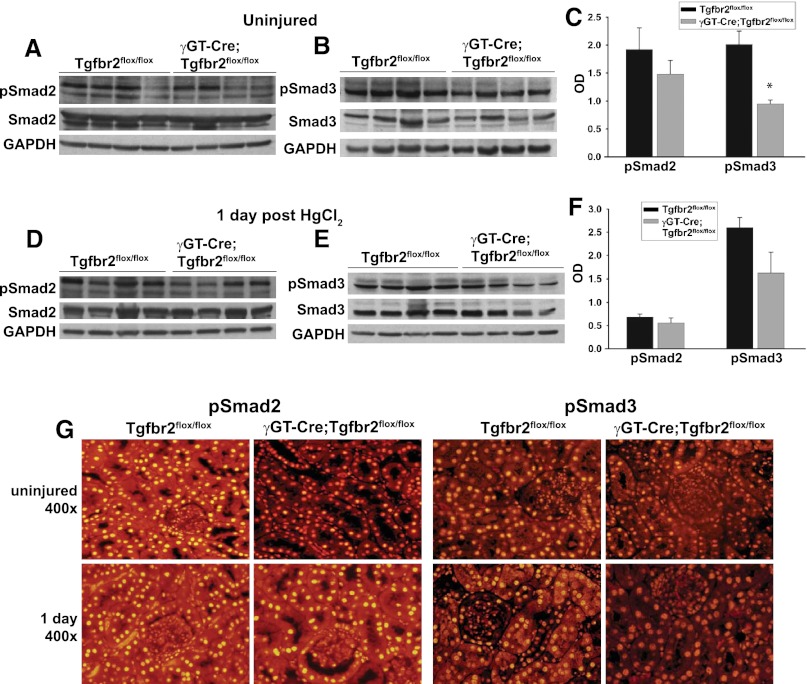

γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox Mice Have Decreased Baseline Smad Activation

To define how deleting TβRII in the proximal tubule affects TGF-β activity, Smad2/3 phosphorylation in the renal cortices of wild-type and the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice was assessed (Figure 5, A–C). Cortical Smad2/3 activation was suppressed in the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox uninjured kidneys (trend was nonsignificant for pSmad2 but significant for pSmad3 at P<0.05), but differences in Smad activation between the two genotypes was lost after injury (Figure 5, D–F). Nuclear accumulation of pSmad2/3, a pattern consistent with activation, was predominantly localized to cortical tubules in both uninjured and injured kidneys (Figure 5J). Thus, deleting TβRII decreases basal Smad signaling, but no significant differences in Smad signaling were noted between the genotypes after HgCl2-induced injury.

Figure 5.

Smad activity is suppressed in γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice. (A–F) Cortical tissue lysates from wild-type and γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice at 0 and 1 day after HgCl2 were immunoblotted for phosphorylated Smad2 (pSmad2), total Smad2, phosphorylated Smad3 (pSmad3), total Smad3, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) for loading. (C, F) Densitometry on phosphorylated Smads2/3 was normalized to GAPDH and reported as means ± SEMs. *P<0.05. (G) Localization of pSmad2/3 was determined by immunofluorescence on paraffin-embedded tissue at 0 and 1 day after injury.

TβRII−/− Proximal Tubule Cells Were Protected against Apoptosis In Vitro

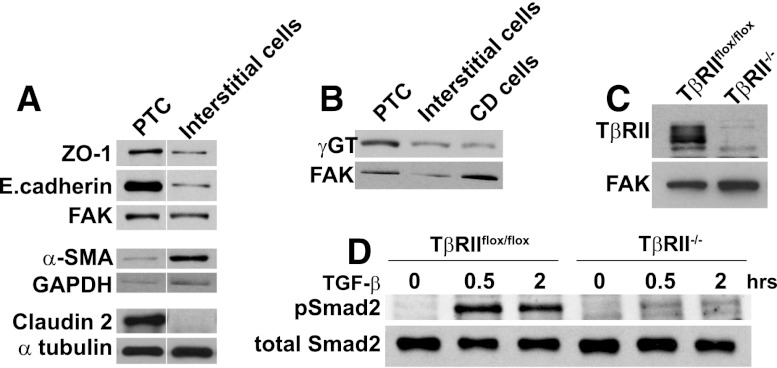

To better understand how TGF-β signaling in proximal tubule cells affects apoptosis, we generated proximal tubule epithelial cells (PTCs) in vitro from Tgfbr2flox/flox mice (see Concise Methods section). Consistent with proximal tubule cells, TβRIIflox/flox PTCs expressed more ZO-1, E.cadherin, and claudin 2, a tight junction protein localized to the proximal tubule and thin descending loop of Henle, but less α-smooth muscle actin compared with interstitial cells (Figure 6A). The PTCs expressed more γGT, an enzyme produced by proximal tubules, than did collecting duct epithelial cells (Figure 6B). TβRII−/− PTCs were produced by infecting the TβRIIflox/flox PTC with adeno-Cre, and deletion of TβRII was confirmed by immunoblots (Figure 6C). TβRII−/− PTCs were unable to respond to TGF-β, as evidenced by a lack of Smad2 phosphorylation, after adding exogenous TGF-β1 (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

PTCs were generated and TβRII deleted in vitro. (A and B) Cell lysates of PTCs, interstitial cells, and collecting duct (CD) cells were immunoblotted for expression of zona occludens-1 (ZO-1), E.cadherin, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), claudin 2, and γ−glutamyltransferase (γGT) with focal adhesion kinase (FAK), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and α tubulin as loading controls. Vertical white lines separate samples rearranged from the same immunoblot. (C) Deletion of TβRII was confirmed by immunoblots of TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs. (D) Cell lysates of TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTC treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) for various time points were immunoblotted for phosphorylated and total levels of Smad2.

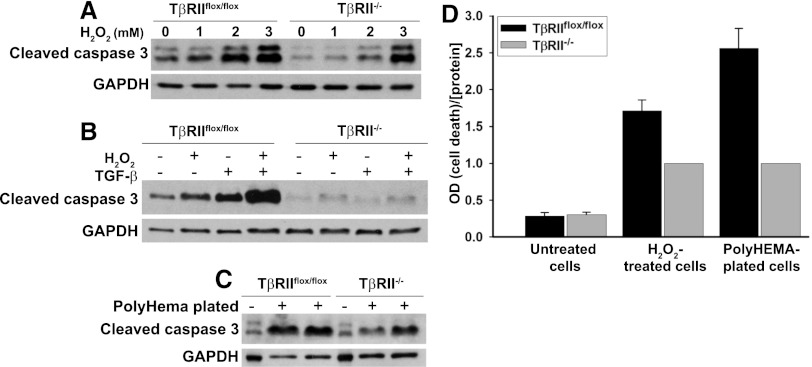

These PTCs were used to assess whether the protective effect of inhibiting TGF-β signaling on apoptosis in vivo could be recapitulated in vitro. Because HgCl2-induced nephrotoxicity is mediated partially by oxidative stress23 and H2O2 is an important reactive oxygen species implicated in toxin-mediated and ischemic AKI, we examined the response of TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs to H2O2. Consistent with our in vivo results, TβRII−/− PTCs had less cleaved caspase 3 than TβRIIflox/flox PTCs after incubation with varying doses of H2O2 for 12 hours (Figure 7A). Also, adding exogenous TGF-β1 was sufficient to induce apoptosis in TβRIIflox/flox PTCs and greatly potentiated its apoptotic response to H2O2, but apoptosis of TβRII−/− PTCs was unaffected by TGF-β1 (Figure 7B). TβRII−/− PTCs were also protected against anoikis, apoptosis due to disruption in cell/matrix interactions, induced by plating on PolyHEMA-coated plates (Sigma) (Figure 7C). The reduction in TβRII−/− PTC apoptosis in response to HO2 and anoikis was confirmed using an apoptosis-specific ELISA (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

TβRII−/− PTC are resistant to apoptosis. (A) TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs were treated with various concentrations of H2O2 for 12 hours, and then immunoblots for cleaved caspase 3 were performed with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a loading control. (B) PTCs were treated with H2O2 (1mM) or TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) for 12 hours and immunoblotted for cleaved caspase 3 and GAPDH. (C) TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs were plated on PolyHEMA-coated plates, as described in the Concise Methods section, for 18 hours to induce anoikis and then immunoblotted for cleaved caspase 3 and GAPDH. (D) The Roche Cell Death ELISA was used to quantify apoptosis in PTCs both treated with H2O2 and plated on PolyHEMA. Experiments were repeated three times, and ratios of cell death to protein concentration were normalized to 1 for TβRII−/− PTCs. The values for untreated cells (negative controls) are expressed relative to TβRII−/− H2O2-treated PTCs as means ± SEMs.

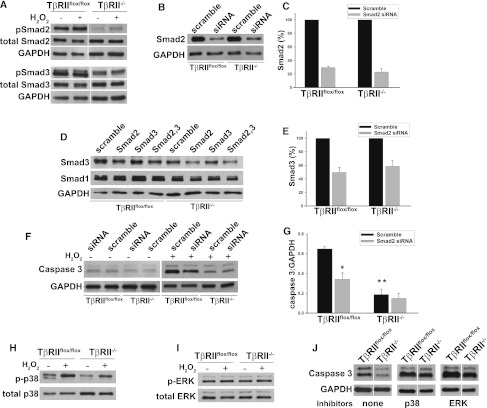

We then examined some relevant downstream signaling pathways responsible for TGF-β–mediated apoptosis in PTCs. We initially investigated Smad2/3 activation and noticed significantly reduced basal levels of phosphorylated Smads2/3 in the TβRII−/− compared with TβRIIflox/flox PTCs (Figure 8A), similar to what we observed in vivo (Figure 5, A–C). H2O2 incubation did not substantially increase this activation in either genotype. The importance of Smad2/3 in apoptosis was defined by knocking down their expression using small interfering RNA (siRNA) (Figure 8, B–E). Smad2 siRNA successfully reduced Smad2 expression (Figure 8B), but several different Smad3 oligonucleotides failed to suppress Smad3 expression. Surprisingly, the Smad2 siRNA also reduced expression of Smad3 (Figure 8, D and E) but did not suppress expression of Smad1 (Figure 8D) or Smad7 (data not shown), thus ruling out nonspecific Smad suppression. Apoptosis in H2O2-treated TβRIIflox/flox PTCs was attenuated with Smad2/3 siRNA, but knocking down Smad2/3 did not affect apoptosis in H2O2-treated TβRII−/− PTCs (Figure 8, F andG).

Figure 8.

Increased apoptosis in TβRIIflox/flox PTCs is partly Smad dependent. (A) Smad2/3 phosphorylation was measured in PTCs at basal conditions and after 30 minutes of H2O2 (1 mM). Vertical white lines separate samples rearranged from the same blot. (B and C) PTCs were transfected with 25 nM Smad2 or scramble siRNA as discussed in the Concise Methods, and knockdown of protein expression was confirmed 4 days later by immunoblots. (C) Smad2 protein expression was quantified by densitometry, normalized to loading controls, and expressed as a percentage of scramble siRNA-treated cells based on the average from three different experiments ± SEM. (D) Smad3 and Smad1 protein expression was measured after transfection with Smad2 (Ambion) with our without Smad3 (Dharmacon) siRNA. (E) Smad2 siRNA reduced expression of Smad3 as quantified by densitometry on three experiments, normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and expressed as a percentage of scramble siRNA ± SEM. (F and G) Lysates of TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs transfected with Smad or scramble siRNA and with or without H2O2 (1 mM) for 12 hours were immunoblotted for cleaved caspase 3 (Caspase 3) and GAPDH as a loading control. (G) Densitometry was performed on three different experiments with the average OD readings shown for H2O2-treated PTCs ± SEMs. *P<0.01 for apoptosis of scramble- versus Smad-siRNA–treated TβRIIflox/flox PTCs. **P<0.01 for the difference in apoptosis between TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs after H2O2. (H and I) PTCs with or without 2 mM H2O2 were immunoblotted for total and phosphorylated p38 and for ERK. (J) TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs treated with no inhibitors, 10 μM p38 inhibitor (SB203582), or 10 μM ERK inhibitor (UO126) were incubated with H2O2 (2 mM) for 12 hours and immunoblotted for cleaved caspase 3 (Caspase 3). The vertical white lines separate samples rearranged in order from the same immunoblot.

Because the MAPK proteins p38 and extracellular receptor kinase (ERK) have both been shown to mediate TGF-β–dependent apoptosis in proximal tubule cells in vitro,13,14 we defined their role in TGF-β–dependent apoptosis after H2O2. Incubation with H2O2 increased p38 but not ERK phosphorylation in both TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs (Figure 8, H and I). Well established chemical inhibitors to p38 and ERK both increased the amount of apoptosis in H2O2-treated TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs to the same extent, suggesting that neither of these pathways mediated TβRII-dependent apoptosis (Figure 8J). These results suggest that the effects of TGF-β signaling on H2O2-induced apoptosis were modulated by Smad2/3 but not by p38 or ERK pathways.

Discussion

TGF-β is well established as a strong profibrotic growth factor in CKD, but its role in AKI is not as well studied and reports of how TGF-β modulates the response to AKI are inconsistent. Unlike previous studies that used systemic inhibition of TGF-β activity, we abrogated TGF-β signaling specifically in the renal proximal tubule and showed that it attenuated the decrease in renal function after HgCl2-induced AKI. This protective effect was associated with reduced tubular apoptosis in vivo. Proximal tubule cells lacking TβRII in vitro were also more resistant to apoptosis induced by H2O2, TGF-β1, and anoikis. Taken together, these findings suggest that TGF-β signaling in the proximal tubule has a detrimental effect on the response to AKI that is partly due to its proapoptotic effects.

The conflicting reports on how TGF-β modulates AKI may be attributed to the different methods used to inhibit TGF-β signaling. Our finding that deleting TβRII is renoprotective is consistent with the attenuated increase in serum creatinine and BUN observed in injured Smad3−/− mice.21 In contrast to these genetic approaches, blocking TGF-β activity with chemical inhibitors did not show a significant effect on renal function after AKI.16,20 Genetic techniques may allow more thorough inhibition of TGF-β activity that is sustained over time, while an inhibitor is generally given at the time of injury and thus lacks the effects of chronic inhibition.

Our studies add to the field of TGF-β and AKI by defining the role of TGF-β signaling specifically in the proximal tubule, the main epithelial cell targeted by AKI. This cell-specific approach is important for understanding the role of TGF-β in renal injury because this growth factor’s variable effects depend on the target cell type and injury. This was demonstrated when we showed previously that deleting TβRII in the collecting system unexpectedly led to increased renal fibrosis in a unilateral ureteral obstruction model.27 This contrasts directly with our present study, in which deleting TβRII in the proximal tubule ameliorated renal injury. The reason for these divergent effects probably relates to the different injury models used. The unilateral ureteral obstruction model generates direct mechanical stress to the epithelium. Because TβRII probably plays an important role in maintaining epithelial integrity,28,29 deleting TβRII renders these epithelial cells more susceptible to stretch-induced injury. In contrast, mercuric chloride does not induce mechanical stress but rather oxidative injury that leads to apoptosis. In this different type of injury, the absence of TβRII was beneficial.

Blocking TGF-β was shown to reduce tubular apoptosis in models of chronic kidney injury,30–32 but this effect in AKI has not been well described. Tubular apoptosis was significantly less in the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox than in the Tgfbr2flox/flox mice after HgCl2, suggesting that resistance to apoptosis is the mechanism protecting from toxin-induced AKI and that TGF-β adversely affects the injury response rather than the repair process.

Although TGF-β was shown to reduce epithelial proliferation and adversely affect inflammation, neither accounted for the improved response to injury in γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice. In fact, the Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had greater proliferation after injury, which is most likely explained by the presence of greater tubular injury, although impaired proliferation in the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice cannot be ruled out. Reduced inflammatory cytokine expression was the putative mechanism whereby Smad3−/− mice were protected from ischemic injury, but there was no quantitative difference in inflammation in our γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox compared with Tgfbr2flox/flox mice after injury. We did not assess qualitative differences in macrophage infiltration or cytokine expression profiles. An important difference between our work and other AKI and TGF-β studies is that we used a mercuric chloride nephrotoxicity model, which has a smaller inflammatory component compared with ischemic models of injury.33

As expected, the γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice had suppressed Smad activation in cortical tubules at baseline, but surprisingly, this difference was not present after injury. Some possible explanations include the following: (1) Deleting TβRII can induce a compensatory upregulation of activins, which can signal through Smads;34 (2) other proteins, such as angiotensin II, can transiently signal through Smads independent of TGF-β; and (3) most of the Smad activation occurs in the tubules, which have undergone significant injury and apoptosis in the Tgfbr2flox/flox mice.

Consistent with our in vivo data, TGF-β1 was sufficient to induce apoptosis in wild-type PTCs, and it potentiated the apoptotic response to oxidative stress (H2O2). In contrast to the paucity of literature on TGF-β and tubular apoptosis in AKI, many reports have described TGF-β’s proapoptotic effect on renal tubular cells in vitro.13,14,35,36 The reduced Smad signaling in proximal tubules lacking TβRII in vivo and in vitro suggests that reduced Smad signaling protects against apoptosis, and this was confirmed with siRNA studies. Smad2/3 signaling may augment apoptosis by altering cell cycle repressor elements or reducing the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2.37,38 Smad pathways have been implicated in TGF-β–mediated apoptosis of other epithelial cells,39 but one study concluded that TGF-β1 augmented proximal tubule apoptosis independent of Smad signaling.13 This study used Smad7 overexpression to inhibit Smad2, which might not be ideal because Smad7 per se promotes apoptosis.40 Unlike in previous reports, the signaling proteins p38 and ERK were protective in our studies, consistent with findings implicating these MAPK pathways in Nrf2-dependent antioxidant production.41,42

A paradigm has emerged in AKI research in which many growth factors (e.g., epidermal growth factor and IGF) are upregulated after injury and facilitate renal repair. Our studies indicate that TGF-β does not fit this paradigm, probably because its proapoptotic effects on epithelial cells outweigh any beneficial effects in the context of AKI. Thus, pharmacologic strategies targeting TGF-β signaling in the proximal tubule may offer a new therapeutic approach to AKI.

Concise Methods

Animal Model

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University and conducted according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Tgfbr2flox/flox mice were crossed with mice containing Cre under control of the γGT promoter (gift from Eric Neilson). The γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox mice were further crossed with the mT/mG reporter mouse (purchased from Jackson Laboratory).

Mercuric Chloride Injury Model

A single injection of HgCl2 (30 μmol/kg diluted in normal saline) was given subcutaneously to γGT-Cre;Tgfbr2flox/flox and Tgfbr2flox/flox male mice that were 8–10 weeks of age and generation 10 on the FVB background. At least five mice per genotype were used and euthanized at 18 hours and 3, 5, and 7 days after HgCl2 injection.

Immunoblots

Cortices were dissected from kidneys of HgCl2-treated mice, placed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2% SDS, 1% Triton, phosphatase and protease inhibitors), sonicated, and clarified by centrifugation. Equal amounts of protein were run on SDS-PAGE gels under reduced conditions, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, blocked in 5% milk, and incubated with various primary antibodies. Appropriate secondary antibodies were used before developing with enhanced chemiluminescence. Primary antibodies were as follows: phospho-Smad2, total Smad2, total Smad3, phospho-ERK, total ERK, phospho-p38, total p38, and cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling); phospho-Smad3, Smad7 (R&D); TβRII (Santa Cruz); F4/80, CD3 (Serotek); ZO-1, Smad1, claudin 2 (Invitrogen); γGT (ANAspec); α-SMA (Sigma); and E.cadherin (BD Biosciences).

Renal Function

Whole blood (<25 μl) was collected daily from HgCl2-treated mice, placed in heparinized tubes, and centrifuged to produce plasma, which was used with the Thermo Infinity Urea Reagent to determine BUN levels. Creatinine levels were determined by HPLC using 30 μl of plasma from a transcardiac puncture at the time of sacrifice by a previously described method (43) with the following modifications: (1) column was Zorbax SCX 2.1 × 100 mm, 5 μm connected to a Zorbax SCX Analytical Guard Column 4.6 × 12.5 mm, 5 μm; (2) mobile phase was 20 mM ammonium formate pH 4.1 at a rate of 0.2 ml/min; (3) absorbance measured at 225 nm with a standard curve of creatinine 25–200 ng.

Immunohistochemistry and Injury Score

Kidneys were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, paraffin embedded, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, or incubated with primary antibodies to Ki-67, F4/80 (Abcam), CD3 (Serotek), pSmad2 (Cell Signaling), pSmad3 (Rockland), or TUNEL staining as previously described.44 Ki-67, TUNEL, F4/80, and CD3 positive tubular cells were quantified in a blinded fashion by counting 10 hpf per mouse and four to six mice per genotype. Renal injury was quantified by a renal pathologist who scored the percentage of tubular necrosis, cellular casts, and tubular injury (epithelial flattening, dilation, loss of brush border) using the following system: 0, <10%; 1, 11%–25%; 2, 26%–50%; 3, >50%. Six mice per genotype were scored in a blinded fashion with 10 fields (200×) reviewed per mouse.

Generation of PTCs

We generated PTCs from our Tgfbr2flox/flox mice crossed with mice containing the Immortomouse transgene (H-2Kb-tsA58)45 using a modified protocol as described by Vinay et al.46 Briefly, cortices were isolated from 6-week-old mice, digested with collagenase, passed through a 70-micron filter, and separated on a Percoll gradient by centrifugation into four bands. The bottom (F4) band was removed, washed, and plated with DMEM/F12 media containing 2.5% FBS, hydrocortisone 50 ng/ml, insulin/transferrin/selenium 5 μg/ml, triiodothyronine 6.5 ng/ml, d-valine 92 μg/ml, and penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin. PTCs were incubated in 33C with interferon-γ 10 ng/ml because the large tumor antigen of the Immortomouse transgene is thermolabile and interferon-inducible. Two weeks before experiments, PTCs in passages two to eight were transferred to 37C and interferon-γ was removed.

Induction of Apoptosis/Anoikis

PTCs were incubated with 1–2 mM H2O2 in serum-free media for 12 hours to induce apoptosis. Inhibitors of ERK/MEK (UO126) and p38 (SB203582) were added to cells 45 minutes before H2O2. Higher doses of H2O2 (2 mM) were used in the experiments with the inhibitors because the carrier DMSO (equal amounts added to controls) had a protective effect on apoptosis. After incubation with H2O2, PTCs were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels for immunoblotting or were treated with the lysis buffer in the Roche Cell Death ELISA; instructions for this kit were followed.

To induce anoikis, 10-cm plates were coated with PolyHEMA (12 mg/ml, Sigma) as previously described.26 After plates dried overnight, they were washed with PBS and plated with 1 million PTCs for 18 hours. The media (and unattached cells) were collected, centrifuged at 200 g for 8 minutes, resuspended in 0.5 ml PBS, and divided in half. One part was centrifuged and resuspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer for immunoblotting, and the other was centrifuged, resuspended in the Roche Cell Death Assay lysis buffer (400 μl), and then further diluted 1:2 for ELISA.

Smad Inhibition with siRNA

TβRIIflox/flox and TβRII−/− PTCs were transfected with Smad2 siRNA (Ambion, Silencer Select predesigned) or scramble negative control (Ambion, Silencer) at 25 nM using lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) overnight. To knock down Smad3, the siRNAs from the following companies were used: Santa Cruz, Ambion (Silencer Select predesigned), and Dharmacon Smart Pool. Four days after transfection, cells were treated with H2O2 (1 mM) for 12 hours, and lysates were made to confirm knockdown of Smad2 and to assess apoptosis by cleaved caspase 3.

Statistical Analyses

We used the t test with unequal variance in Excel to compare two sets of data, with P<0.05 representing a statistically significant difference. All experiments subject to analysis were performed at least three times.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jorge Capdevila for performing HPLC, Hal Moses for providing the Tgfbr2flox/flox mouse, and Eric Neilson for the mouse containing γGT-Cre.

This work was supported by a Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development (L.G.), a Vanderbilt Physician Scientist Development Award (L.G.), Pediatric Nephrology Center of Excellence (L.G.), Merit Awards from the Department of Veterans Affairs (A.P., R.C.H., R.Z.), DK075594 (R.Z.), DK069221, DK65123 (R.Z. and A.P.), DK083187 (R.Z.), DK51265 (R.C.H.), DK062794 (R.C.H.), the O’Brien Center DK79341-01 (A.P., R.H.C., R.Z.), and an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award (R.Z.). This material is based upon work supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Veterans Affairs Tennessee Valley Healthcare System.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Humes HD, Cieslinski DA, Coimbra TM, Messana JM, Galvao C: Epidermal growth factor enhances renal tubule cell regeneration and repair and accelerates the recovery of renal function in postischemic acute renal failure. J Clin Invest 84: 1757–1761, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coimbra TM, Cieslinski DA, Humes HD: Epidermal growth factor accelerates renal repair in mercuric chloride nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol 259: F438–F443, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller SB, Martin DR, Kissane J, Hammerman MR: Insulin-like growth factor I accelerates recovery from ischemic acute tubular necrosis in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89: 11876–11880, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller SB, Martin DR, Kissane J, Hammerman MR: Hepatocyte growth factor accelerates recovery from acute ischemic renal injury in rats. Am J Physiol 266: F129–F134, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wrana JL, Attisano L, Cárcamo J, Zentella A, Doody J, Laiho M, Wang XF, Massagué J: TGF beta signals through a heteromeric protein kinase receptor complex. Cell 71: 1003–1014, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashita H, ten Dijke P, Franzén P, Miyazono K, Heldin CH: Formation of hetero-oligomeric complexes of type I and type II receptors for transforming growth factor-beta. J Biol Chem 269: 20172–20178, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashida T, Decaestecker M, Schnaper HW: Cross-talk between ERK MAP kinase and Smad signaling pathways enhances TGF-beta-dependent responses in human mesangial cells. FASEB J 17: 1576–1578, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang S, Wilkes MC, Leof EB, Hirschberg R: Noncanonical TGF-beta pathways, mTORC1 and Abl, in renal interstitial fibrogenesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F142–F149, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witzgall R, Brown D, Schwarz C, Bonventre JV: Localization of proliferating cell nuclear antigen, vimentin, c-Fos, and clusterin in the postischemic kidney. Evidence for a heterogenous genetic response among nephron segments, and a large pool of mitotically active and dedifferentiated cells. J Clin Invest 93: 2175–2188, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishibe S, Cantley LG: Epithelial-mesenchymal-epithelial cycling in kidney repair. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17: 379–385, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boland S, Boisvieux-Ulrich E, Houcine O, Baeza-Squiban A, Pouchelet M, Schoëvaërt D, Marano F: TGF beta 1 promotes actin cytoskeleton reorganization and migratory phenotype in epithelial tracheal cells in primary culture. J Cell Sci 109: 2207–2219, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ignotz RA, Massagué J: Cell adhesion protein receptors as targets for transforming growth factor-beta action. Cell 51: 189–197, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dai C, Yang J, Liu Y: Transforming growth factor-beta1 potentiates renal tubular epithelial cell death by a mechanism independent of Smad signaling. J Biol Chem 278: 12537–12545, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshikawa M, Hishikawa K, Idei M, Fujita T: Trichostatin a prevents TGF-beta1-induced apoptosis by inhibiting ERK activation in human renal tubular epithelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol 642: 28–36, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havasi A, Borkan SC: Apoptosis and acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 80: 29–40, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geng H, Lan R, Wang G, Siddiqi AR, Naski MC, Brooks AI, Barnes JL, Saikumar P, Weinberg JM, Venkatachalam MA: Inhibition of autoregulated TGFbeta signaling simultaneously enhances proliferation and differentiation of kidney epithelium and promotes repair following renal ischemia. Am J Pathol 174: 1291–1308, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan Q, Nguan CY, Du C: Expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 limits renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplantation 89: 1320–1327, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HT, Kim M, Kim J, Kim N, Emala CW: TGF-beta1 release by volatile anesthetics mediates protection against renal proximal tubule cell necrosis. Am J Nephrol 27: 416–424, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HT, Chen SW, Doetschman TC, Deng C, D’Agati VD, Kim M: Sevoflurane protects against renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice via the transforming growth factor-beta1 pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F128–F136, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spurgeon KR, Donohoe DL, Basile DP: Transforming growth factor-beta in acute renal failure: Receptor expression, effects on proliferation, cellularity, and vascularization after recovery from injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F568–F577, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nath KA, Croatt AJ, Warner GM, Grande JP: Genetic deficiency of Smad3 protects against murine ischemic acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F436–F442, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Chen JK, Wang SW, Moeckel G, Harris RC: Importance of functional EGF receptors in recovery from acute nephrotoxic injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 3147–3154, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zalups RK: Molecular interactions with mercury in the kidney. Pharmacol Rev 52: 113–143, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamond GL, Zalups RK: Understanding renal toxicity of heavy metals. Toxicol Pathol 26: 92–103, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG: Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest 110: 341–350, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh AB, Sugimoto K, Harris RC: Juxtacrine activation of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor by membrane-anchored heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor protects epithelial cells from anoikis while maintaining an epithelial phenotype. J Biol Chem 282: 32890–32901, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gewin L, Bulus N, Mernaugh G, Moeckel G, Harris RC, Moses HL, Pozzi A, Zent R: TGF-beta receptor deletion in the renal collecting system exacerbates fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1334–1343, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Böttinger EP, Jakubczak JL, Roberts IS, Mumy M, Hemmati P, Bagnall K, Merlino G, Wakefield LM: Expression of a dominant-negative mutant TGF-beta type II receptor in transgenic mice reveals essential roles for TGF-beta in regulation of growth and differentiation in the exocrine pancreas. EMBO J 16: 2621–2633, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonniaud P, Kolb M, Galt T, Robertson J, Robbins C, Stampfli M, Lavery C, Margetts PJ, Roberts AB, Gauldie J: Smad3 null mice develop airspace enlargement and are resistant to TGF-beta-mediated pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol 173: 2099–2108, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyajima A, Chen J, Lawrence C, Ledbetter S, Soslow RA, Stern J, Jha S, Pigato J, Lemer ML, Poppas DP, Vaughan ED, Felsen D: Antibody to transforming growth factor-beta ameliorates tubular apoptosis in unilateral ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int 58: 2301–2313, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling H, Li X, Jha S, Wang W, Karetskaya L, Pratt B, Ledbetter S: Therapeutic role of TGF-beta-neutralizing antibody in mouse cyclosporin A nephropathy: Morphologic improvement associated with functional preservation. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 377–388, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanderson N, Factor V, Nagy P, Kopp J, Kondaiah P, Wakefield L, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Thorgeirsson SS: Hepatic expression of mature transforming growth factor beta 1 in transgenic mice results in multiple tissue lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92: 2572–2576, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jo SK, Hu X, Kobayashi H, Lizak M, Miyaji T, Koretsky A, Star RA: Detection of inflammation following renal ischemia by magnetic resonance imaging. Kidney Int 64: 43–51, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oe S, Lemmer ER, Conner EA, Factor VM, Levéen P, Larsson J, Karlsson S, Thorgeirsson SS: Intact signaling by transforming growth factor beta is not required for termination of liver regeneration in mice. Hepatology 40: 1098–1105, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarabishi R, Zahedi K, Mishra J, Ma Q, Kelly C, Tehrani K, Devarajan P: Induction of Zf9 in the kidney following early ischemia/reperfusion. Kidney Int 68: 1511–1519, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nowak G, Schnellmann RG: Autocrine production and TGF-beta 1-mediated effects on metabolism and viability in renal cells. Am J Physiol 271: F689–F697, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J, Song K, Krebs TL, Jackson MW, Danielpour D: Rb/E2F4 and Smad2/3 link survivin to TGF-beta-induced apoptosis and tumor progression. Oncogene 27: 5326–5338, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang YA, Zhang GM, Feigenbaum L, Zhang YE: Smad3 reduces susceptibility to hepatocarcinoma by sensitizing hepatocytes to apoptosis through downregulation of Bcl-2. Cancer Cell 9: 445–457, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xavier S, Niranjan T, Krick S, Zhang T, Ju W, Shaw AS, Schiffer M, Böttinger EP: TbetaRI independently activates Smad- and CD2AP-dependent pathways in podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2127–2137, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okado T, Terada Y, Tanaka H, Inoshita S, Nakao A, Sasaki S: Smad7 mediates transforming growth factor-beta-induced apoptosis in mesangial cells. Kidney Int 62: 1178–1186, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao P, Nussler A, Liu L, Hao L, Song F, Schirmeier A, Nussler N: Quercetin protects human hepatocytes from ethanol-derived oxidative stress by inducing heme oxygenase-1 via the MAPK/Nrf2 pathways. J Hepatol 47: 253–261, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xing HY, Liu Y, Chen JH, Sun FJ, Shi HQ, Xia PY: Hyperoside attenuates hydrogen peroxide-induced L02 cell damage via MAPK-dependent Keap₁-Nrf₂-ARE signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 410: 759–765, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunn SR, Qi Z, Bottinger EP, Breyer MD, Sharma K: Utility of endogenous creatinine clearance as a measure of renal function in mice. Kidney Int 65: 1959–1967, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Srichai MB, Hao C, Davis L, Golovin A, Zhao M, Moeckel G, Dunn S, Bulus N, Harris RC, Zent R, Breyer MD: Apoptosis of the thick ascending limb results in acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1538–1546, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jat PS, Noble MD, Ataliotis P, Tanaka Y, Yannoutsos N, Larsen L, Kioussis D: Direct derivation of conditionally immortal cell lines from an H-2Kb-tsA58 transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88: 5096–5100, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vinay P, Gougoux A, Lemieux G: Isolation of a pure suspension of rat proximal tubules. Am J Physiol 241: F403–F411, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]