Abstract

Background

Higher total serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentrations have been associated with better cognitive function mainly in cross-sectional studies in adults. It is unknown if the associations of different forms of 25(OH)D (25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2) are similar.

Methods

Prospective cohort study (n=3171) with serum 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 concentrations measured at mean age of 9.8 years and academic performance at age 13–14 years (total scores in English, mathematics and science) and 15–16 years (performance in General Certificates of Education examinations).

Results

Serum 25(OH)D3 concentrations were not associated with any educational outcomes. Higher 25(OH)D2 concentrations were associated with worse performance in English at age 13–14 years (adjusted SD change per doubling in 25(OH)D2 (95% CI) −0.05 (−0.08 to −0.01)) and with worse academic performance at age 15–16 years (adjusted OR for obtaining ≥5 A*–C grades (95% CI) 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00)).

Conclusion

The null findings with 25(OH)D3 are in line with two previous cross-sectional studies in children. It is possible that the positive association of 25(OH)D with cognitive function seen in adults does not emerge until later in life or that the results from previous cross-sectional adult studies are due to reverse causality. The unexpected inverse association of 25(OH)D2 with academic performance requires replication in further studies. Taken together, our findings do not support suggestions that children should have controlled exposure to sunlight, or vitamin D supplements, in order to increase academic performance.

Keywords: 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, child, adolescent, cognitive function, ALSPAC, epidemiology, cognition, child health, asthma, atopy

Introduction

Cognitive function in childhood and educational attainment are associated with adverse health outcomes in adulthood.1–9 These associations are approximately linear across the full distribution of cognitive function/education, rather than being driven by adverse health in those with severe learning difficulties.9 Understanding the determinants of childhood cognitive function and educational attainment are important for understanding the mechanisms linking this to later health and for developing means to improve educational attainment and later health and well-being.

Higher serum concentrations of total 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) have been associated with better cognitive function in some,10–15 though not all,16 17 epidemiological studies of adults. To our knowledge, only two studies have examined this association in children; both these cross-sectional studies used data from the Third US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) and found no association between total 25(OH)D and childhood cognitive function.17 18

Circulatory 25(OH)D consists of 25(OH)D3 (synthesised from vitamin D3 obtained mainly from ultraviolet B (UVB) induced synthesis in skin and to a lesser extent from animal food sources) and 25(OH)D2 (synthesised from vitamin D2 obtained from plant/fungal sources). There is evidence that vitamin D3 supplementation is more potent in raising and maintaining 25(OH)D concentrations than supplementation with vitamin D2.19 It is unknown if these two forms of 25(OH)D have similar associations with cognitive function.

The aim of this study was to examine the prospective association between variation in serum 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 with academic performance in children and to compare if these associations were similar with both forms of 25(OH)D. Because vitamin D, together with parathyroid hormone (PTH), regulates calcium and phosphate homoeostasis,20 21 we investigated whether these analytes were related to academic performance and whether the association of 25(OH)D3 and or 25(OH)D2 was independent of PTH, calcium or phosphate.

Methods

Population

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) is a population-based birth cohort from South West England. The cohort consisted of 14 062 live births from 14 541 enrolled pregnant women who were expected to give birth between 1 April 1991 and 31 December 1992.22 From age 7, all children were invited for an annual assessment of physical and psychological development. Parents gave informed consent at enrolment, and ethical approval was obtained from the ALSPAC Law and Ethics Research Committee and local research ethics committee. Permission to use education data was sought from the accompanying adult at the 7-year clinic.

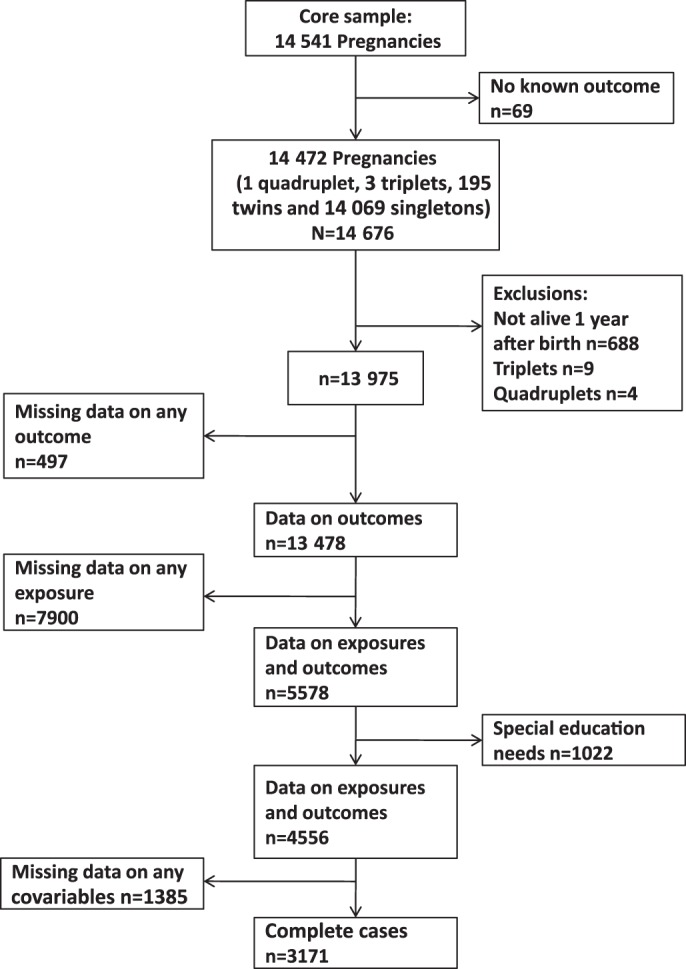

Single and twin births were included in this study. Those with any special education needs at the first four academic performance assessments (key stage (KS) assessments) were excluded. Figure 1 shows the flow through the cohort of participants and how the number included in the analyses presented here was derived. In total, 3171 participants with complete data on both exposures, all outcomes and confounders were included in our analyses.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants.

Exposures and related blood-based covariables

Serum 25(OH)D3, 25(OH)D2, PTH, phosphate and calcium were assayed on non-fasting blood samples collected at mean age of 9.9 years for the majority of participants. If no samples were available from the 9.9 years assessment, samples from mean age of 11.8 years or, second, the 7.6 years assessment were used. The mean age at sample collection in the whole study sample was 9.8 years (SD: 1.1). Following collection, samples were immediately spun, frozen and stored at –80°C. Assays were performed after a maximum of 12 years in storage, with no previous freeze-thaw cycles. 25(OH)D3, 25(OH)D2 and deuterated internal standard were measured with high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometer using multiple reaction mode with following mass:charge ratio transitions: 413.2>395.3, 401.1>383.3 and 407.5>107.2 for 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3 and hexa-deuterated (OH)D3, respectively. Interassay coefficients of variation for the assay were <10% across a working range of 2.5–624 nmol/l for both 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2.

Total serum calcium, phosphate and albumin concentrations were measured by standard laboratory methods on Roche Modular analysers (Roche Diagnostics Ltd, West Sussex, UK). Serum calcium was adjusted for albumin using a normogram of calcium and albumin distributions of the samples analysed in the clinical chemistry laboratory where the measurements were performed. Albumin-adjusted calcium concentrations were used in all statistical analyses. Intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH(1–84)) was measured by electrochemiluminescent immunoassay on an Elecsys 2010 immunoanalyzer (Roche, Lewes, UK). Interassay coefficient of variation was <6% from 2 to 50 pmol/l. The assay sensitivity (replicates of the zero standard) was 1 pmol/l.

Outcomes

KS3 and KS4 results were obtained by linkage to National Pupil Database, a central repository for pupil-level annual school census, using unique pupil numbers as identifiers. KS3 tests are performed at 13–14 years (school year 9) when performance in English, maths and science is assessed. Total point scores in each subject were used in the analyses. KS4 is performed at 15–16 years when pupils take their General Certificates of Education in a range of academic and applied subjects. General Certificates of Education are graded from A* to G, with A* indicating the highest performance. We examined associations with three outcomes from KS4 assessments: (1) those achieving five or more A*–C grades, including maths and English (this variable is provided in the National Pupil Data set and is the level of achievement generally required to go on to advance level study and ultimately university; many semi-skilled jobs that do not require a university degree also consider this an important achievement); (2) those achieving nine or more A*–A (an indicator of the highest performers) and (3) those achieving no A*–C grades (an indicator of poor performance).

Confounders

Data on ethnicity, maternal and paternal education and occupational social class were obtained from parent-completed questionnaires. Data on subsidised school meals were obtained from the National Pupil Database. Data on time spent outdoors and protection from UVB exposure (use of sunblock, covering clothing or hat and avoidance of midday sun) were obtained from parent-completed questionnaires at mean age of 8.5 years. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and weight measured at the same time as blood samples were taken. IQ was assessed by the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IIIUK) at the 8–9-year assessment.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with Stata V.11.0 (Stata Corp LP). To adjust for seasonal variability, 25(OH)D3 was modelled according to date of blood sampling using linear regression with trigonometric sine and cosine functions. 25(OH)D3 was loge transformed to reduce heteroscedasticity. The residual from the sine–cosine date of sampling regression model was then used as the primary 25(OH)D3 exposure variable in subsequent regression analyses. To include all participants on whom a 25(OH)D2 was assayed, those with a value below the detectable limit of the assay (1.25 nmol/l, n=1147, 36%) were given a value of 1.25 nmol/l and indicated using a binary covariable in all regression models.

Age and gender SD (z) scores for serum 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3, PTH, calcium and phosphate were generated using the internal cohort data with age in 1 month categories. The association of potential confounders with KS3 outcomes and with exposures was assessed with linear regression, and the association of confounders with KS4 outcomes was assessed with logistic regression.

The associations of 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 with KS3 and KS4 results were assessed with non-parametric bootstrap procedure in conjunction with multilevel mixed-effects linear regression (for KS3 outcomes) or random-effects logit models (for KS4 outcomes) based on 10 000 replications. The multilevel mixed-effects linear regression and random-effects logit models were used to take into account the school-level variance in the KS results, and the bootstrapping procedure enabled us to statistically compare associations of 25(OH)D2 to those of 25(OH)D3. The difference between the association of 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 was calculated from the bootstrap replicate distribution. β-Estimates and SEs were empirically calculated from the mean and SD of the bootstrap distribution, respectively. All p values were calculated using bootstrap means and SEs and compared to a z-distribution. To numerically compare the associations of two forms of 25(OH)D, β-coefficients from the regression models were multiplied by loge(2). These are then interpreted as mean differences or ORs per doubling of exposure. For the main analyses presented here, we compared the associations of season-adjusted 25(OH)D3 to those of 25(OH)D2. The associations of unadjusted (for season) 25(OH)D3 and total 25(OH)D (25(OH)D3, with no seasonal adjustment, plus 25(OH)D2) with all outcomes are shown in the supplementary material.

Results

The mean (SD) seasonally adjusted serum 25(OH)D3, phosphate and albumin-adjusted calcium concentration were 62.1 (0.8) nmol/l, 1.53 (0.16) mmol/l and 2.38 (0.12) mmol/l, respectively. The median (IQR) for serum 25(OH)D2 and PTH were 3.2 (1.3–6.7) nmol/l and 4.4 (3.3–5.8) pmol/l, respectively. Mean (SD) score in KS3 English, maths and science examinations were 54 (15), 89 (20) and 102 (22), respectively.

Supplementary table 1 shows the distribution of outcomes and confounders in participants with data on outcomes who were excluded due to missing data in exposures or confounders and in complete cases. Complete cases were more likely to perform better in both KS examinations, have higher IQ and lower BMI, to be of white ethnicity, less meticulous about protection from UVB and from higher socioeconomic backgrounds than those with missing data on exposures or confounders.

Supplementary table 2 shows the associations of potential confounders with 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3, PTH, calcium and phosphate. Those with non-white ethnicity had higher PTH and lower 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 concentrations. BMI was negatively associated with serum 25(OH)D3 and positively with PTH concentrations. Higher socioeconomic position was associated with higher concentrations of 25(OH)D3 and phosphate and lower concentrations of 25(OH)D2 and calcium. Children who were protected more from UVB exposure had lower 25(OH)D3, phosphate and PTH concentrations and higher calcium concentrations. Time spent outdoors during summer was positively associated with 25(OH)D3 concentrations. Pupils who were eligible for free school meals had lower 25(OH)D3 and higher 25(OH)D2 and PTH concentrations.

Supplementary table 3 shows the associations of potential confounders with KS3 scores. Non-white ethnicity, higher BMI, lower socioeconomic position, being more meticulous about avoiding UVB exposure and spending less time outdoors were all associated with lower examination scores in at least one of English, maths or science. Supplementary table 4 summarises the associations of potential confounders and academic performance in KS4. In general, these associations were similar to those found with KS3 scores.

Table 1 shows the prospective associations of serum 25(OH)D3, 25(OH)D2, calcium, phosphate and PTH concentrations with KS3 scores. 25(OH)D3 concentrations were not associated with any KS3 outcomes. Higher 25(OH)D2 concentrations were associated with worse performance in English in the unadjusted model (model 1) and after adjusting for confounders including ethnicity, socioeconomic position, protection from UVB (model 2) and for other analytes, including 25(OH)D3 (model 3). 25(OH)D2 was not associated with performance in maths or science. The associations of 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 with English were different from each other (p=0.01). None of PTH, calcium or phosphate was associated with KS3 outcomes in confounder-adjusted models.

Table 1.

Prospective association of 25(OH)D3, 25(OH)D2, phosphate, calcium and PTH concentrations (assessed at mean age of 9.8 years with key stage 3 scores (assessed at age 13–14 years) (n=3171)

| Exposure | Outcome | SD change in outcome per doubling of exposure (95% CI) | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

| 25(OH)D3 | English total score | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) |

| Maths total score | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.03) | |

| Science total score | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.02) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.02) | |

| 25(OH)D2 | English total score | −0.07 (−0.10 to −0.04) | −0.05 (−0.08 to −0.02) | −0.05 (−0.08 to −0.01) |

| Maths total score | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.06) | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.07) | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.06) | |

| Science total score | −0.03 (−0.06 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.02) | |

| Albumin-adjusted calcium | English total score | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.02) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) |

| Maths total score | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | |

| Science total score | 0.00 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | |

| Phosphate | English total score | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) |

| Maths total score | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | |

| Science total score | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.05) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.04) | |

| Parathyroid hormone | English total score | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | −0.02 (−0.04 to 0.00) | −0.02 (−0.04 to 0.00) |

| Maths total score | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.03) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.03) | |

| Science total score | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | 0.00 (−0.02 to 0.02) | |

Model 1 is unadjusted (the exposures are standardised for age and gender and 25(OH)D3 is adjusted for season and ethnicity).

Model 2 same as model 1 plus adjustment for ethnicity, head of household social class, mothers and partners education, time spent outdoors during summer (age 8.5 years), use of sunblock, hat, covering clothing, avoidance of midday sun, body mass index and eligibility for free school meals.

Model 3 same as model 2 plus adjustment for serum concentrations of other hormones/metabolites, which are related 25(OH)D3 homoeostasis (eg, association of 25(OH)D3 is adjusted for 25(OH)D2, phosphate, albumin-adjusted calcium and parathyroid hormone).

Table 2 shows the prospective association between exposures and KS4 outcomes. These were essentially consistent with findings seen for KS3 outcomes. 25(OH)D3 was not associated with any of the KS4 outcomes, and higher serum 25(OH)D2 concentrations were associated with worse academic performance (less likely to obtain ≥5 A*–C grades or ≥9 A*–A grades) in the unadjusted model (model 1). These inverse associations attenuated slightly with adjustment for potential confounders (model 2), with additional adjustment for other analytes, including 25(OH)D3 not changing results further (model 3). There was statistical evidence that the associations of 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 with obtaining ≥5 A*–C grades differed from each other (p=0.02). PTH, calcium and phosphate concentrations were not associated with any KS4 outcomes, with the exception of phosphate having a modest positive association with obtaining ≥5 A*–C grades. The associations of unadjusted (for season) 25(OH)D3 and total 25(OH)D concentrations with educational outcomes were similar to those of season-adjusted 25(OH)D3 shown here (supplementary tables 5 and 6).

Table 2.

Prospective association of 25(OH)D3, 25(OH)D2, phosphate, calcium and PTH concentrations (assessed at mean age of 9.8 years) with key stage 4 educational attainment (age 15–16 years) (n=3171)

| Exposure | Outcome | OR per doubling of exposure (95% CI) | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

| 25(OH)D3 | Achieved 5 or more A*–C grades | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.10) | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.09) | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.09) |

| Achieved 9 or more A*–A grades | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.07) | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.08) | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.08) | |

| Did not achieve any A*–C grades | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.05) | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.09) | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.08) | |

| 25(OH)D2 | Achieved 5 or more A*–C grades | 0.89 (0.82 to 0.98) | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00) | 0.90 (0.82 to 1.00) |

| Achieved 9 or more A*–A grades | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.91) | 0.84 (0.74 to 0.96) | 0.84 (0.73 to 0.97) | |

| Did not achieve any A*–C grades | 1.16 (1.02 to 1.34) | 1.12 (0.96 to 1.29) | 1.12 (0.96 to 1.30) | |

| Albumin-adjusted calcium | Achieved 5 or more A*–C grades | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.05) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.09) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.08) |

| Achieved 9 or more A*–A grades | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.04) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.08) | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.10) | |

| Did not achieve any A*–C grades | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.09) | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.06) | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.03) | |

| Phosphate | Achieved 5 or more A*–C grades | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.12) | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.11) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) |

| Achieved 9 or more A*–A grades | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.08) | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.05) | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.06) | |

| Did not achieve any A*–C grades | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.15) | 1.07 (0.98 to 1.16) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.19) | |

| Parathyroid hormone | Achieved 5 or more A*–C grades | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.05) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.06) |

| Achieved 9 or more A*–A grades | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.05) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.04) | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.05) | |

| Did not achieve any A*–C grades | 1.02 (0.94 to 1.11) | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.14) | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | |

Model 1 is unadjusted (the exposures are standardised for age and gender and 25(OH)D3 is adjusted for season and ethnicity).

Model 2 same as model 1 plus adjustment for ethnicity, head of household social class, mothers and partners education, time spent outdoors during summer (age 8.5 years), use of sunblock, hat, covering clothing, avoidance of midday sun, body mass index and eligibility for free school meals.

Model 3 same as model 2 plus adjustment for serum concentrations of other hormones/metabolites, which are related 25(OH)D3 homeostasis (eg, association of 25(OH)D3 is adjusted for 25(OH)D2, phosphate, albumin-adjusted calcium and parathyroid hormone).

Supplementary tables 7 and 8 show the results of sensitivity analyses restricted to participants with data on IQ at age 8.5 years and exposure measurements at age 9.9 or 11.8 years. Adjustment for IQ at age 8.5 years, in addition to other confounders, did not alter the inverse associations of 25(OH)D2 with outcomes.

Discussion

Serum 25(OH)D3 concentrations, at age 7.6–11.8 years, were not associated with academic performance assessed at age 13–14 or 15–16 years in our prospective study. Somewhat surprisingly serum concentrations of 25(OH)D2 were negatively associated with academic achievements. This association was consistent with the associations of indicators of lower socioeconomic position (eg, eligibility for free school meals, lower parental education and socioeconomic position) with lower educational attainment and higher 25(OH)D2 concentrations. It is therefore possible that it represents residual confounding. There was little evidence that PTH, calcium or phosphate were associated with educational attainment. These findings build on two previous cross-sectional studies in children using NHANES data that reported no associations of total 25(OH)D or calcium with cognitive function.17 18 Since 25(OH)D3 is the major contributor to total 25(OH)D,23 our findings of no association of 25(OH)D3 or calcium with academic performance are consistent with these studies. This is illustrated in our cohort by the lack of association of total 25 (OH)D (supplementary table 6) with any of the educational outcomes.

Most cross-sectional10 12–15 and one of the two prospective11 studies in adults have shown a positive association between total 25(OH)D concentrations and cognitive function, though a recent second prospective study found no association between total 25(OH)D and cognitive decline.16 The difference between the overall body of evidence in adults (suggesting better cognitive function in those with higher vitamin D) compared with children (no association) could be because the key effects of 25(OH)D only emerge in adults either because it is related more to cognitive decline than development or because it is a lifetime cumulative amount of vitamin D that is important with respect to cognitive function. Alternatively, it could be that studies of adults (which are mostly cross-sectional) are more likely to be affected by reverse causality than those in childhood (with adults with poorer cognitive function spending less time outdoors and hence having lower 25(OH)D concentrations).

Experimental studies suggest that vitamin D and its metabolites are important for neuronal function.24–26 The findings from these studies suggest that vitamin D may be linked to cognition by different pathways, including mediation of inflammatory response, regulation of genes that mediate neuronal density, synaptic plasticity, neurotransmitter synthesis and survival and differentiation of neurons, as well as direct functions as a neurotrophic and neuroprotective factor.27 Although animal studies have shown that vitamin D-deficient animals often display behavioural abnormalities and different learning patterns, there are some inconsistencies in these results (reviewed in McCann and Ames27 and Eyles et al 28). The majority of the animal studies have used vitamin D receptor knockout models or restricted the UV irradiation/dietary intake of vitamin D3, which would provide more information on the effects of vitamin D3 and its metabolites. Thus, it is difficult to suggest a biological mechanism, which could explain the negative association between 25(OH)D2 and academic performance based on these possible pathways. One possibility is that this is a chance finding given the number of associations that have been examined in this paper and the lack of any previous studies (that we are aware of) that have examined the associations of 25(OH)D2 specifically with cognitive or educational outcomes. It is also possible that despite extensive adjustment for potential confounders, the association is explained by residual confounding and different confounder structures between the two forms of 25(OH)D. The main source of 25(OH)D2 are diet and supplements, whereas that of 25(OH)D3 is UVB exposure. Dietary behaviours may be more likely to be affected by multiple confounders that could generate the 25(OH)D2 association than is UVB exposure. However, for this to be the case, we would need to think of a (or several) confounders that are related to higher levels of consumption of food that is a source of 25(OH)D2 (mostly supplements) and lower educational attainment.

Strengths and weaknesses

In addition to examining prospective associations, the strengths of the present study include large sample size, ability to adjust for multiple confounders and the measurement methodology for 25(OH)D concentrations. With one exception,16 previous studies of associations in adults and children have used immunoassays, which may underestimate the amount of 25(OH)D2,29 30 or 25(OH)D in general,31 32 and do not enable the separate measurements of 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3. It is valuable to examine the associations of these two forms of vitamin D with outcomes because supplements are available in both forms, and until recently vitamin D supplements (as opposed to multivitamin supplements) have largely been 25(OH)D2. There is debate about whether the two forms have equivalent potency and whether vitamin D2 supplements are valuable means of increasing total 25(OH)D in humans.19 33 Thus, it is important to know whether the two forms of 25(OH)D do have similar associations with outcomes.

Similar to other prospective cohort studies, there was loss to follow-up and those who have attended follow-up clinics tend to be from higher socioeconomic groups.22 Complete cases were more likely to perform better in KS examinations and be from higher socioeconomic backgrounds than children who were excluded from analyses due to missing data. This may have some implications for the generalisability of the results as children with lower educational attainment were under-represented in the complete case analyses. However, it is unlikely that the associations between vitamin D metabolites and educational attainment would be different in those with missing data. The prevalence of low 25(OH)D concentrations was similar to previous studies (27% of our study population had total 25(OH)D concentration below 20 ng/ml) so our results are likely to be generalisable to most Northern hemisphere populations with similar vitamin D concentrations but may not generalise to those with very different dietary intakes or UVB exposure.

We used academic performance instead of standardised tests of cognitive function, which might complicate the comparison with other studies using IQ tests. Academic performance correlates with IQ test scores (r∼0.5),34 and the correlation coefficients between the full IQ score in Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children at the age of 8.5 years and KS2 and KS3 scores in ALSPAC are similar to these published associations (based on cross-sectional data), ranging between 0.29 and 0.66. Lastly, examining associations with actual educational performance has the advantage that this is a more proximal predictor of future health and well-being and mediates many of the associations of childhood cognition with later adult health outcomes.5–7 We only used data from a single measurement of 25(OH)D3, 25(OH)D2, phosphate, calcium and PTH concentrations, which may be inadequate,35 although a single measurement may be a useful biomarker of season-specific vitamin D status over a longer time,36 and serum calcium concentrations are normally maintained at relatively narrow limits within individuals.37

In conclusion, despite biological evidence that variation in vitamin D and associated biomarkers might influence brain development and hence cognitive function,10 11 28 38 our prospective study suggests that neither 25(OH)D3 nor total 25(OH)D is an important determinant of academic performance in children and that 25(OH)D2 is actually inversely associated with performance. The increasing number of association studies suggesting that low levels of vitamin D are related to a wide range of health outcomes, including cognitive function, have resulted in calls for changes to public health guidance regarding extreme protection against UV exposure. However, our results suggest that protection of children from UVB exposure, which has been associated with low levels of vitamin D, but which protects against skin damage and skin cancer, is unlikely to have any detrimental effect on academic achievement.

What is already known on this subject.

Higher total serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentrations have been associated with better cognitive function mainly in cross-sectional studies of adults. There are few prospective studies, and none of these are in children.

25(OH)D is present in two forms: 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2, but it is unknown if the associations of these two forms with cognitive performance are similar.

What this study adds.

Our prospective study suggests that 25(OH)D3 is not an important determinant of academic performance in children and that 25(OH)D2 is inversely associated with performance, though this may be a chance finding or due to residual confounding.

Protection of children from ultraviolet B exposure, which has been associated with low concentrations of vitamin D, but which protects against skin damage and skin cancer, is unlikely to have any detrimental effect on academic achievement.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses.

Footnotes

Contributors: Planned the research project: A-MT and DAL. Obtained funding: DAL. Provided essential materials: WDF (laboratory analyses). Data analysis: A-MT and AS. Supervised the analyses and project: DAL. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: A-MT and DAL. Accepted the final manuscript and made important intellectual contribution to draft versions: A-MT, AS, WDF and DAL. Acts as guarantor: A-MT.

Funding: Work on this study is funded by an UK Medical Research Council (MRC) Grant G0701603, which also pays A-MT's salary. Salary support for AS is provided by Wellcome Trust grant ref 079960. MRC, the Wellcome Trust and the University of Bristol provide core funding support for ALSPAC. The MRC and the University of Bristol provide core funding for the MRC Centre of Causal Analyses in Translational Epidemiology (Grant G0600705). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of any funding body or others whose support is acknowledged. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: ALSPAC Law and Ethics Research Committee and local research ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Whalley LJ, Deary IJ. Longitudinal cohort study of childhood IQ and survival up to age 76. BMJ 2001;322:819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hart CL, Taylor MD, Davey Smith G, et al. Childhood IQ, social class, deprivation, and their relationships with mortality and morbidity risk in later life: prospective observational study linking the Scottish Mental Survey 1932 and the Midspan studies. Psychosom Med 2003;65:877–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Osler M, Andersen AM, Due P, et al. Socioeconomic position in early life, birth weight, childhood cognitive function, and adult mortality. A longitudinal study of Danish men born in 1953. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:681–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Osler M, Lawlor DA, Nordentoft M. Cognitive function in childhood and early adulthood and hospital admission for schizophrenia and bipolar disorders in Danish men born in 1953. Schizophr Res 2007;92:132–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lawlor DA, Clark H, Leon DA. Associations between childhood intelligence and hospital admissions for unintentional injuries in adulthood: the Aberdeen children of the 1950s cohort study. Am J Public Health 2007;97:291–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lawlor DA, Batty GD, Clark H, et al. Association of childhood intelligence with risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: findings from the Aberdeen children of the 1950s cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23:695–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leon DA, Lawlor DA, Clark H, et al. The association of childhood intelligence with mortality risk from adolescence to middle age: findings from the Aberdeen children of the 1950s cohort study. Intelligence 2009;37:520–8 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lager A, Bremberg S, Vagero D. The association of early IQ and education with mortality: 65 year longitudinal study in Malmo, Sweden. BMJ 2009;339:b5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Batty GD, Whitley E, Deary IJ, et al. Psychosis alters association between IQ and future risk of attempted suicide: cohort study of 1,109,475 Swedish men. BMJ 2010;340:c2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Llewellyn DJ, Langa KM, Lang IA. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2009;22:188–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Langa KM, et al. Vitamin D and risk of cognitive decline in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1135–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buell JS, Scott TM, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Vitamin D is associated with cognitive function in elders receiving home health services. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:888–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buell JS, Dawson-Hughes B, Scott TM, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, dementia, and cerebrovascular pathology in elders receiving home services. Neurology 2010;74:18–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Annweiler C, Schott AM, Allali G, et al. Association of vitamin D deficiency with cognitive impairment in older women. Cross-sectional study. Neurology 2010;74:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee DM, Tajar A, Ulubaev A, et al. Association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and cognitive performance in middle-aged and older European men. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:722–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Slinin Y, Paudel ML, Taylor BC, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D levels and cognitive performance and decline in elderly men. Neurology 2010;74:33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGrath J, Scragg R, Chant D, et al. No association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 level and performance on psychometric tests in NHANES III. Neuroepidemiology 2007;29:49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tolppanen AM, Williams D, Lawlor DA. The association of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and calcium with cognitive performance in adolescents: cross-sectional study using data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2011;25:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heaney RP, Recker RR, Grote J, et al. Vitamin D3 is more potent than vitamin D2 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;96:E447–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown AJ, Dusso A, Slatopolsky E, et al. Vitamin D. Am J Physiol 1999;277:F157–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mundy GR, Guise TA. Hormonal control of calcium homeostasis. Clin Chem 1999;45:1347–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Golding J, Pembrey M, Jones R. ALSPAC–the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. I. Study methodology. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2001;15:74–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holick MF. Vitamin D: a millenium perspective. J Cell Biochem 2003;88:296–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Almeras L, Eyles D, Benech P, et al. Developmental vitamin D deficiency alters brain protein expression in the adult rat: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Proteomics 2007;7:769–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eyles D, Brown J, Mackay-Sim A, et al. Vitamin D3 and brain development. Neuroscience 2003;118:641–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, et al. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat 2005;29:21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCann JC, Ames BN. Is there convincing biological or behavioral evidence linking vitamin D deficiency to brain dysfunction? FASEB J 2008;22:982–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eyles DW, Feron F, Cui X, et al. Developmental vitamin D deficiency causes abnormal brain development. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009;34(Suppl 1):S247–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glendenning P, Taranto M, Noble JM, et al. Current assays overestimate 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and underestimate 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 compared with HPLC: need for assay-specific decision limits and metabolite-specific assays. Ann Clin Biochem 2006;43:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Binkley N, Krueger D, Cowgill CS, et al. Assay variation confounds the diagnosis of hypovitaminosis D: a call for standardization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:3152–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carter GD, Jones JC, Berry JL. The anomalous behaviour of exogenous 25-hydroxyvitamin D in competitive binding assays. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2007;103:480–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lai JK, Lucas RM, Clements MS, et al. Assessing vitamin D status: pitfalls for the unwary. Mol Nutr Food Res 2010;54:1062–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Houghton LA, Vieth R. The case against ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) as a vitamin supplement. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:694–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Neisser U, Boodoo G, Bouchard TJ, et al. Intelligence: knowns and unknowns. Am Psychol 1996;51:77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schram MT, Trompet S, Kamper AM, et al. Serum calcium and cognitive function in old age. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1786–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hofmann JN, Yu K, Horst RL, et al. Long-term variation in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration among participants in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 2010;19:927–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parfitt AM. Bone and plasma calcium homeostasis. Bone 1987;8(Suppl 1):S1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Buell JS, Dawson-Hughes B. Vitamin D and neurocognitive dysfunction: preventing “D”ecline? Mol Aspects Med 2008;29:415–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]