Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate in a prospective, randomized study, the efficacy and safety profile of photoselective vaporization of prostate (PVP) using a 80W potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser when compared to standard transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) due to benign prostatic enlargement (BPE).

Materials and Methods:

Between February 2009 and August 2009, 117 patients satisfying the eligibility criteria underwent surgery [60 PVP{Group A}; 57 TURP{Group B}]. The groups were compared for functional outcome (both subjective and objective parameters), perioperative parameters and complications, with a follow up of one year. P value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

The baseline characteristics of the two groups were comparable. Mean age was 66.68 years and 65.74 years, mean IPSS score was 19.98 and 20.88, mean prostate volume was 44.77 cc and 49.02 cc in Group A and B, respectively. Improvements in IPSS, QOL, prostate volume, Q max and PVRU at 12 months were similar in both groups. PVP patients had longer operating time, lesser perioperative blood loss, shorter catheterization time and a higher dysuria rate when compared to TURP patients. The overall complication rate was similar in the two groups.

Conclusions:

In patients with LUTS due to BPE, KTP-PVP is an equally efficacious alternative to TURP with durable results at one year follow up with additional benefits of lesser perioperative blood loss, lesser transfusion requirements and a shorter catheterization time. Long term comparative data is awaited to clearly define the role of KTP-PVP in such patients.

Keywords: Benign prostatic hyperplasia, green light laser, potassium titanyl phosphate laser, photoselective vaporization, transurethral resection of prostate

INTRODUCTION

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is still viewed as the “benchmark for surgical therapies” for benign prostatic enlargement (BPE).[1] Even though the mortality and short-term morbidity rates following TURP in contemporary series are much lesser than in the older series (0.1% vs. 0.2% mortality rate, 11.1% vs. 18% morbidity rate), they still remain an area of concern to the urologist.[2,3] Further, TURP is a technically demanding procedure requiring substantial practice to master it. The learning curve for TURP, as most urologists would agree, ranges from 50-100 cases and this level of experience is often not reached by the end of the residency training period because of the dramatic decrease in the overall TURPs being performed annually. These, among other factors have driven the search for a safer, easier to perform alternative that is as efficacious as TURP for the surgical management of BPE.

Among the emerging surgical therapies for BPE, laser is the most promising. Potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser, also known as “Green Light” laser is one such laser with a wavelength of 532 nm. It is selectively absorbed by hemoglobin within prostatic tissue, thus permitting photoselective vaporization of prostate (PVP). KTP-PVP is considered to be easier to learn and perform than TURP and competence occurs following 5-20 procedures.[4] Even though KTP-PVP is being done now for well over a decade, data comparing KTP-PVP with standard TURP is sparse. We performed a prospective, randomized study to examine the efficacy and safety profile of KTP-PVP when compared to standard TURP.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study protocol and all procedures were approved by the institutional ethics committee. Between February 2009 and August 2009, consecutive patients attending the Urology OPD with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign prostatic enlargement (BPE) who satisfied the eligibility criteria (inclusion/exclusion criteria) and who were planned for surgery according to the International BPH guidelines of the American Urology Association were included in this prospective, randomized study.[1] Inclusion criteria: a] Age > 50 years, b] IPSS>7, c] Prostate volume (TRUS): >20 and < 80 cc, d] Q max < 15 ml/sec. Exclusion criteria: a] History of prostate, bladder or urethral surgery. b] History of spinal surgery or spinal trauma. c] Neurological disease. d] PVRU>300cc. e] Patient presenting with an indwelling Foley's catheter where indication for catheterization was chronic retention(PVRU >300). f] Patients diagnosed with carcinoma prostate, carcinoma bladder, stricture urethra. g] Patients receiving alpha blocker/5 alpha reductase inhibitor drugs/herbal medications believed to be active in prostate. h] Patients on antiplatelet drugs where drugs could not be safely stopped perioperatively. i] Patients who did not give written informed consent.

Initial evaluation included a detailed clinical history including the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), quality of life (QOL) score and international index of erectile function (IIEF5) score, physical examination including digital rectal and focused neurological examination, urinalysis, serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) measurement, prostate volume estimation by transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), post-void residual urine (PVRU) measurement by abdominal ultrasound and Qmax (maximum flow rate) measurement on uroflowmetry (UFR). {PVRU and UFR measurement were not done in patients who were on catheter consequent to acute retention of urine. Such patients were eligible if all other criteria were met with}. If the digital rectal examination was abnormal and/or the PSA was > 4 ng/ml, a 12-core TRUS-guided prostatic biopsy was performed preoperatively to rule out prostate cancer. Patients in whom prostate cancer was diagnosed were excluded from the study. Eligible patients were randomized to one of two groups. Group A: underwent PVP using the 80W KTP laser. Group B underwent standard TURP. Randomization was done in a 1:1 ratio using a sealed envelope sequence. No crossover occurred after treatment group allocation.

Surgical procedure

All procedures were performed by one of the three consultant urologists in our department, each of whom were skilled in TURP but had performed <5 KTP-PVP prior to this study. All three surgeons performed nearly equal number of KTP-PVPs and TURPs.

Group A

For PVP, a continuous flow 23F laserscope was used. The lens employed was a 30-degree lens and the irrigant used was 0.9% sodium chloride. The fiber was a 600 micron, 70 degree side firing laser fiber emitting green light at 532 nm. At first the median lobe (when present) was lased and thereafter the lateral lobes were lased in a symmetrical manner. Anterior vaporization if needed, was then performed. Tissue was vaporized down to the prostatic capsule until an unobstructed view of the trigone and a TURP like cavity was obtained. Vaporization was achieved by moving the laser fiber slowly and constantly in a “paint brush fashion” taking care to keep the fiber in “near contact” with the prostatic tissue. If any bleeding vessels were encountered during vaporization, coagulation was accomplished by defocusing the laser fiber (increasing working distance to 3-4 mm) or by reducing the power setting to 30W from 80W.

Group B

TURP was done using a 26F continuous flow resectoscope. The lens employed was a 30-degree lens and the irrigant used was 1.5% Glycine. A standard tungsten cutting wire loop at a setting of 160 W cutting and 80 W coagulation was used. The resection was carried down to the surgical capsule from bladder neck up to the verumontanum.

Since all procedures (in both groups) were done under spinal anesthesia, in all patients, an indwelling 22F three-way Foley's catheter was inserted into the bladder. Irrigation with 0.9% normal saline was started postoperatively if deemed necessary until the urine was sufficiently clear. As an institutional policy, catheter is removed 24 h after the irrigation is stopped and the urine is sufficiently clear. For the purpose of this study, catheter removal was decided by a urologist who was unaware of the procedure that the patient had undergone. Patients who failed trial without catheter were recatheterized and a voiding trial was given again after one week. All patients received an intravenous antibiotic at induction and an oral antibiotic was continued till five days post catheter removal.

Intraoperative and postoperative parameters recorded included the operative time (measured as equivalent to the time the resectoscope/laserscope was inside the urethra), amount of irrigation fluid used intraoperatively, whether postoperative irrigation was instituted, amount of irrigation fluid used in the postoperative period, duration of postoperative irrigation, duration of catheterization and postoperative hemoglobin concentration. All patients were followed up in the urology outpatient department at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months. At each follow-up visit, IPSS, QOL, IIEF 5, Qmax, PVRU, residual prostate volume (assessed by transrectal ultrasound) and complications, if any were recorded. Neither the patient nor the outcome assessor was blinded to the procedure the patient had undergone.

Primary outcome measures for group analysis (PVP vs. TURP) included:

Subjective (IPSS, QOL, IIEF5) parameters

Objective (Prostate volume, PVRU and Qmax) parameters.

Secondary outcome measures for group analysis included:

Perioperative parameters: Operative time, amount of irrigation fluid used intraoperatively, whether postoperative irrigation was instituted, amount of irrigation fluid used in the postoperative period, duration of postoperative irrigation, duration of catheterization (defined as time to initial removal of the catheter), postoperative hemoglobin concentration (sample taken on the morning after surgery).

Complications, if any.

Statistical analysis

Observations were recorded and arranged on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Seattle, WA USA) and analyzed by SPSS Version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), software package. The calculated sample size was 130 patients (65 per arm) with a power of 80%. The parametric outcomes were expressed as the mean ± SD of the group. The two-tailed Student t-test was used as a statistical tool to see the significance level between the groups. Categorical data in perioperative or complications outcome were analyzed by the nonparametric Mann-Whitney “U” test, chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

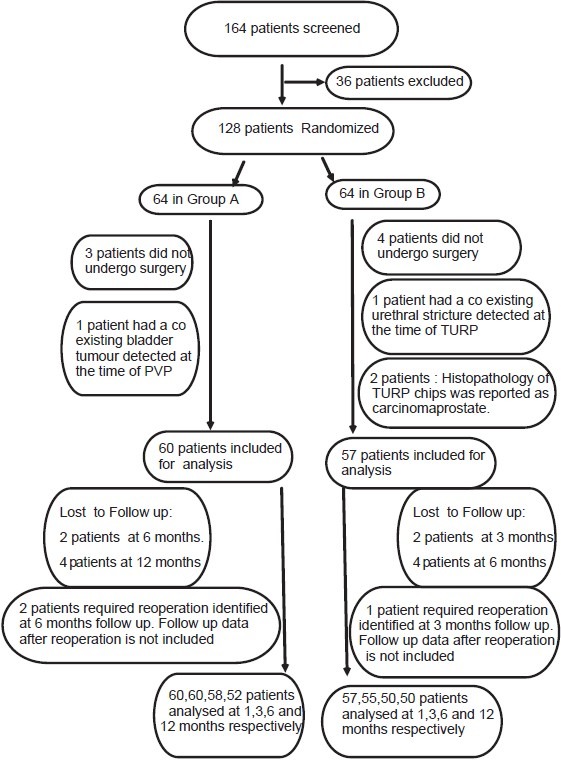

Of 164 patients screened, 128 were found eligible and were randomized, 64 each to Group A and B respectively, of which four and seven patients in Group A and B respectively were subsequently excluded leaving 60 and 57 patients in Group A and B respectively available for analysis. Follow-up data at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months was available for 60, 60, 58, 52 and 57, 55, 50, 50 patients in Group A and B respectively [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Allocation and dispersion of patients

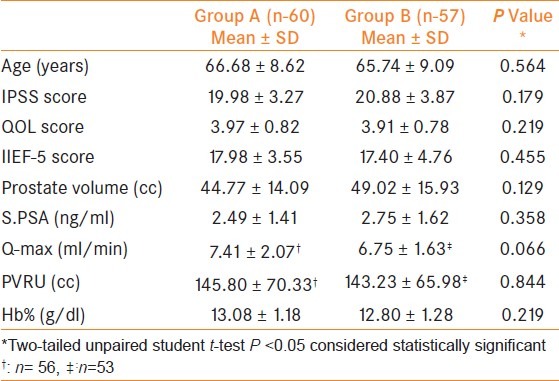

The baseline characteristics of the two groups including mean age, IPSS score, QOL score, IIEF-5 score, prostate volume, serum PSA, Qmax, PVRU, and preoperative hemoglobin were similar with no significant differences noted [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

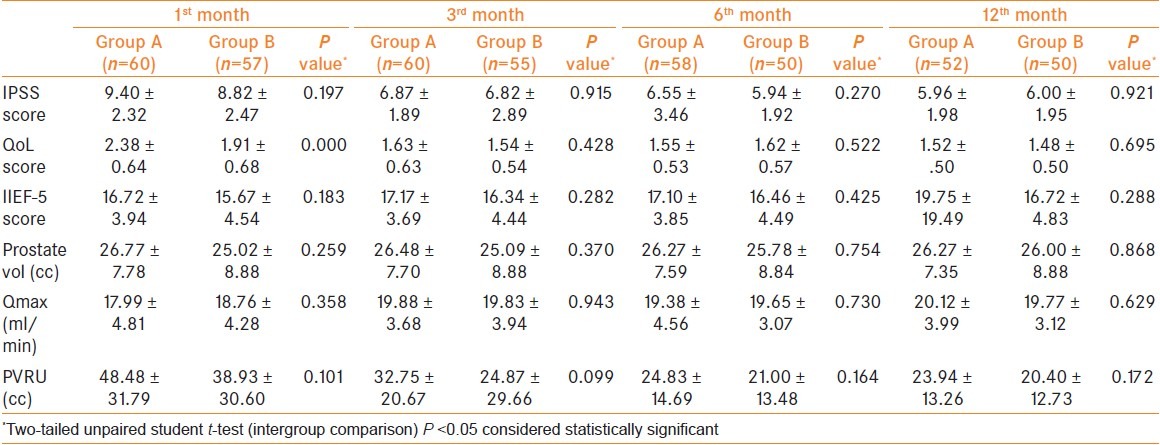

Follow-up data is summarized in Table 2. In both groups, there was significant improvement in the IPSS score, QOL score, prostate volume, Qmax and PVRU, as compared to the baseline at each of the follow-up visits with the most dramatic improvement being seen at the first month follow-up. IIEF-5 scores did not show any significant improvement in either group at any of the follow-up visits. Overall IPSS score decreased by 70.17% and 71.26%, QOL score decreased by 61.71% and 62.15%, prostate volume decreased by 41.32% and 46.96%, Qmax increased by 171.52% and 192.89%, PVRU decreased by 83.53% and 85.76% at 12 months in Group A and B, respectively. Between the two groups, there was no significant difference in the IPSS score, QOL score, IIEF-5 score, prostate volume, Qmax and PVRU at each of the follow-up visits except for QOL score at one month which was significantly better in Group B.

Table 2.

Follow-up data

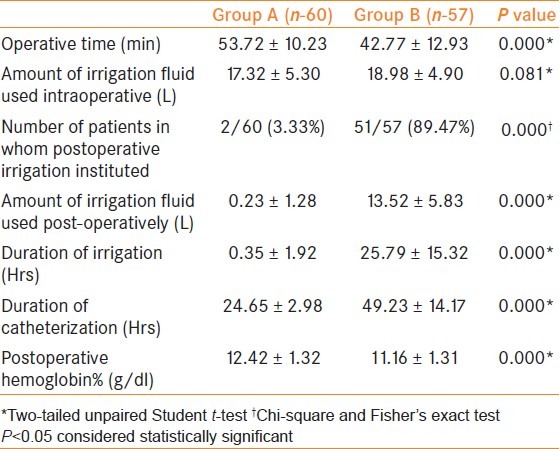

Data pertaining to the perioperative period is summarized in Table 3. Operative time was significantly longer in Group A when compared to Group B. The need, amount and duration of postoperative irrigation along with duration of postoperative catheterization were all significantly lesser in Group A as compared to Group B. The postoperative hemoglobin percentage was significantly higher in Group A as compared to Group B.

Table 3.

Perioperative data

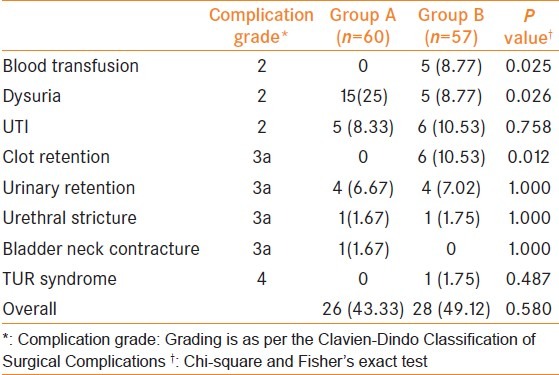

The complications in each of the two groups are summarized in Table 4. Although the overall complication rate did not differ significantly between the two groups, the rate of clot retention and that of blood transfusion was significantly higher in Group B when compared to Group A. Dysuria in the early postoperative period was significantly more common in Group A as compared to Group B [15 in Group A vs. 5 in Group B]. Phenazopyridine was prescribed when dysuria was not related to a positive urine culture. Dysuria resolved by the end of one month in all except one patient of Group A in whom it took three months to resolve. Four patients each in Group A and B had urinary retention after catheter removal. Re-trial given after one week was successful in all eight patients. As per the ClavienDindo Classification of Surgical Complications, no significant differences between the two groups were noted insofar as the different grades of complications were concerned.[5] Amongst the three operating surgeons, complication rates were similar with no significant differences noted.

Table 4.

Complications

DISCUSSION

The Green light laser system, initially introduced as part of a hybrid technique with Nd:YAG laser, evolved to stand alone Green light laser with gradually increasing power as studies proved efficacy and safety.[6] The first clinical experience with pure KTP-PVP was reported by Malek in 1998 who used a 60W laser.[7] Subsequently, the 80W KTP laser was introduced. Various authors with follow-up ranging from one to five years have reported favorably on the efficacy and safety profile of KTP-PVP.[8–15] Further, favorable outcomes have been reported for KTP-PVP even in high-risk patients and in those with larger glands.[16–19]

Insofar as data comparing KTP-PVP with TURP is concerned, the literature is sparse. The first prospective though non-randomized comparison between KTP-PVP and TURP with a six-month follow-up was reported by Bachmann et al., in 2005. They found that though the overall perioperative complication rates between the two groups were similar, patients undergoing PVP had significantly lesser drop in hemoglobin percentage and serum sodium postoperatively. Further, the PVP group had a significantly shorter catheter time and hospital stay. As far as improvement in IPSS, QOL, Qmax and PVRU was concerned, no significant difference was noted between the two groups at six months.[20] Intermediate term results with two-year follow-up of the above mentioned prospective non-randomized study were published in 2008. The authors reported that the rates of intraoperative bleeding, blood transfusion, capsular perforation and postoperative clot retention were significantly lower in patients in the PVP group whereas the incidence of urethral and bladder neck strictures did not differ significantly between the two groups. Catheterization time and hospital stay were significantly lesser in the PVP group for patients in the <70 years and 70-80 years’ subgroups. Though improvement in Qmax and decrease in prostate volume and PSA were significantly higher in the TURP group, improvement in IPSS and PVRU did not differ significantly between the two groups. The authors concluded that KTP-PVP was more favorable in terms of perioperative safety and had comparable functional outcomes.[21]

A single prospective randomized comparative study between KTP-PVP (80W) and TURP has been published so far. The authors, Bouchier-Hayes et al., having earlier published interim results in 2006, recently published their final data.[22,23] Of 119 patients randomized, 10 refused surgery leaving 50 and 59 patients who underwent TURP AND KTP-PVP respectively. Of these 39 and 46 patients in the TURP and KTP-PVP groups respectively, were available for analysis at 12 months. Both groups showed significant improvements in IPSS, QOL, Bother score, Qmax and PVRU at 12 months when compared to the baseline with no significant difference noted between them. Patients undergoing KTP-PVP had significantly shorter catheterization time (13 vs. 44.2 h), shorter length of inpatient stay (1.09 vs. 3.6 days) and lesser blood loss. Further, complications were less frequent in the KTP-PVP group.

Our study has shown that at one-year follow-up, efficacy of KTP-PVP is comparable to TURP with no significant differences noted. As far as safety is concerned, KTP-PVP was associated with significantly less blood loss, clot retention and transfusion rates, even though the overall complication rate did not differ significantly when compared to the TURP group. Similar overall complication rates in this study must be interpreted in the context that while the operators were skilled in TURP prior to the start of this study, the learning curve of the operators for KTP-PVP is part of this study. A case in point is the rate of transient dysuria in Group A. In our study, 25% of KTP-PVP patients complained of transient dysuria in the early postoperative period, a much higher rate than that reported in other KTP-PVP series.[20,21,23] Dysuria is primarily caused by coagulation rather than vaporization of the tissue and its severity correlates with the volume of coagulated tissue. Excessive coagulation may be related to operator factors and/or patient factors.[4] A possible explanation of the higher rate of dysuria in our study could be the limited experience of the operators with PVP to begin with, since in the first 10 cases of each operator, 3, 4 and 4 patients respectively developed transient dysuria. Subsequently, in the remaining 30 patients who underwent PVP, only 4 developed transient dysuria.

One drawback of this study is that since patients with prostate volumes >80 cc were excluded, the results of this study cannot be extrapolated to BPE patients with larger prostates. Further, though the efficacy of KTP-PVP is evident up to the one-year follow-up, no comment can be made on long-term durability.

CONCLUSIONS

KTP-PVP is an equally efficacious alternative to TURP in the management of LUTS due to BPE with durable results at one-year follow-up. It has the added benefits of significantly lesser perioperative blood loss and transfusion requirements along with a shorter catheterization time. More long term studies are needed to clearly define the place of KTP-PVP in the management of patients with BPE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Mr. Ajay Prakash for his help in data analysis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.AUA Practice Guidelines Committee. AUA guideline on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (2003).Chapter 1: Diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Urol. 2003;170:530–47. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000078083.38675.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, Cockett AT, Peters PC. Transurethral prostatectomy: Immediate and postoperative complications. A cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. J Urol. 1989;141:243–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40731-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reich O, Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Seitz M, Schlenker B, Hermanek P, et al. Morbidity, mortality and early outcome of transurethral resection of the prostate: A prospective multicenter evaluation of 10,654 patients. J Urol. 2008;180:246–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wosnitzer MS, Rutman MP. KTP/LBO Laser Vaporization of the Prostate. Urol Clin North Am. 2009;36:471–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Strasberg SM. Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1992;111:518–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson G. Contact laser prostatectomy. World J Urol. 1995;13:115–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00183625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malek RS, Barrett DM, Kuntzman RS. High-power potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP/532) laser vaporization prostatectomy: 24 hours later. Urology. 1998;51:254–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hai MA, Malek RS. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate: Initial experience with a new 80 W KTP laser for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Endourol. 2003;17:93–6. doi: 10.1089/08927790360587414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Te AE, Malloy TR, Stein BS, Ulchaker JC, Nseyo UO, Hai MA, et al. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: 12-month results from the first United States multicenter prospective trial. J Urol. 2004;172:1404–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000139541.68542.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malek RS, Kuntzman RS, Barrett DM. Photoselective potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vaporization of the benign obstructive prostate: Observations on long-term outcomes. J Urol. 2005;174:1344–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000173913.41401.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachmann A, Ruszat R, Wyler S, Reich O, Seifert HH, Muller A, et al. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate: The basel experience after 108 procedures. Eur Urol. 2005;47:798–804. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarica K, Alkan E, Luleci H, Taşci AI. Photoselective vaporization of the enlarged prostate with KTP laser: Long-term results in 240 patients. J Endourol. 2005;19:1199–202. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seki N, Nomura H, Yamaguchi A, Naito S. Effects of photoselective vaporization of the prostate on urodynamics in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2008;180:1024–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamann MF, Naumann CM, Seif C, Van der Horst C, Junemann KP, Braun PM. Functional outcome following photoselective vaporisation of the prostate (PVP): Urodynamic findings within 12 months follow-up. Eur Urol. 2008;54:902–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruszat R, Seitz M, Wyler SF, Abe C, Rieken M, Reich O, et al. GreenLight laser vaporization of the prostate: Single-center experience and long-term results after 500 procedures. Eur Urol. 2008;54:893–901. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reich O, Bachmann A, Siebels M, Hofstetter A, Stief CG, Sulser T. High power (80 W) potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vaporization of the prostate in 66 high risk patients. J Urol. 2005;173:158–60. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000146631.14200.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu WJ, Hong BF, Wang XX, Yang Y, Cai W, Gao JP, et al. Evaluation of GreenLight photoselective vaporization of the prostate for the treatment of high-risk patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian J Androl. 2006;8:367–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2006.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruszat R, Wyler S, Forster T, Reich O, Stief CG, Gasser TC, et al. Safety and effectiveness of photoselective vaporization of the prostate (PVP) in patients on ongoing oral anticoagulation. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1031–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajbabu K, Chandrasekara SK, Barber NJ, Walsh K, Muir GH. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate with the potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser in men with prostates of >100 mL. BJU Int. 2007;100:593–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bachmann A, Schurch L, Ruszat R, Wyler SF, Seifert HH, Muller A, et al. Photoselective vaporization (PVP) versus transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP): A prospective bicentre study of perioperative morbidity and early functional outcome. Eur Urol. 2005;48:965–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruszat R, Wyler SF, Seitz M, Lehmann K, Abe C, Bonkat G, et al. Comparison of potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vaporization of the prostate and transurethral resection of the prostate: Update of a prospective non-randomized two-centre study. BJU Int. 2008;102:1432–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouchier-Hayes DM, Anderson P, Van Appledorn S, Bugeja P, Costello AJ. KTP laser versus transurethral resection: Early results of a randomized trial. J Endourol. 2006;20:580–5. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouchier-Hayes DM, Van Appledorn S, Bugeja P, Crowe H, Challacombe B, Costello AJ. A randomized trial of photoselective vaporization of the prostate using the 80-W potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vs transurethral prostatectomy, with a 1-year follow-up. BJU Int. 2010;105:964–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]