Chromatin structure and function is based on the dynamic interactions between nucleosomes and chromatin-associated proteins. In addition to the other post-translational modifications considered in this review issue of Biopolymers, ubiquitin and SUMO proteins also have prominent roles in chromatin function. A specialized form of modification that involves both, referred to as SUMO-Targeted Ubiquitin Ligation, or STUbL1, has significant effects on nuclear functions, ranging from gene regulation to genomic stability. Intersections between SUMO and ubiquitin in protein modification have been the subject of a recent comprehensive review.2 Our goal here is to focus on features of enzymes with STUbL activity that have been best studied, particularly in relation to their nuclear functions in humans, flies and yeasts. Because there are clear associations of disease and development upon loss of STUbL activities in metazoans, learning more about their function, regulation, and substrates will remain an important goal for the future.

SUMO and STUbL

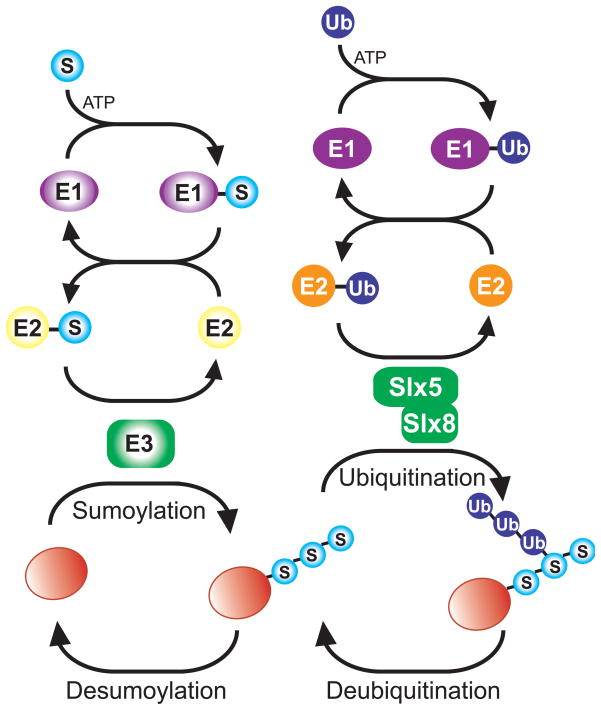

The ubiquitin-like protein SUMO modifies hundreds of proteins in yeast3–8, and is featured prominently in the proteomes of more complex eukaryotes as well9–11. As depicted in Fig. 1, SUMO is covalently attached to target lysine residues of a substrate through the enzymatic action of an E1 SUMO activating enzyme, an E2 SUMO conjugating enzyme, and multiple E3 SUMO ligases, in a manner similar to that by which ubiquitin is covalently attached to protein substrates (reviewed in 12). Because one of the roles of ubiquitination is proteasome-mediated degradation, the initial model for SUMO function was that it blocked protein degradation by out-competing ubiquitin for shared lysine residue targets. Now it is well established that sumoylation affects substrates in diverse ways, and in some cases, promotes degradation. Similar to ubiquitin proteases and the ubiquitin cycle, SUMO proteases provided components to define the SUMO cycle (reviewed in 13).

Figure 1.

Intersection of sumoylation and SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligation (STUbL) pathways. Cartoon shows similarity of enzymatic cascades of SUMO (S) and Ubiquitin (Ub) pathways. The SUMO-interacting motifs (not pictured) of the heterodimeric Slx5-Slx8 STUbL (solid green) mediate the interaction between the sumoylated substrate (red ball with light blue SUMO chain) and the STUbL. Ubiquitination by STUbL (dark blue Ub chain) may occur on the SUMO chain and/or the substrate (not shown). For dynamic regulation SUMO and Ubiquitin modifications may be removed by their respective proteases.

Results from yeast two-hybrid assays helped to identify common features shared among SUMO binding proteins.4 Members of this distinct class of proteins that interact directly with SUMO share what is now commonly referred to as SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs), which are composed of a string of hydrophobic residues that may be flanked either N- or C-terminally by acidic residues.14 Some of the SIM-containing proteins are involved in SUMO dynamics but the biological relevance of most SIM-containing candidate proteins remains under study.15 Results obtained with application of SIM-prediction and bioinformatics tools do not always overlap with the experimental results but will nonetheless be useful to identify potential SIMs.16,17 Clearly, a combination of sequence analysis and mutational analysis will be required to establish the functional significance of SIMs in these proteins.

A subset of SIM-containing proteins has the distinct RING domain commonly found in E3 ubiquitin ligases. As with other ubiquitin ligases, specificity is conferred by domains that mediate protein-protein interactions between substrates and E3 ubiquitin ligases, which in this case, are SIMS. Further research established that SIM-containing E3 ubiquitin ligases named SUMO-Targeted Ubiquitin Ligases (STUbLs) are evolutionarily conserved from yeast to man.1

Localization

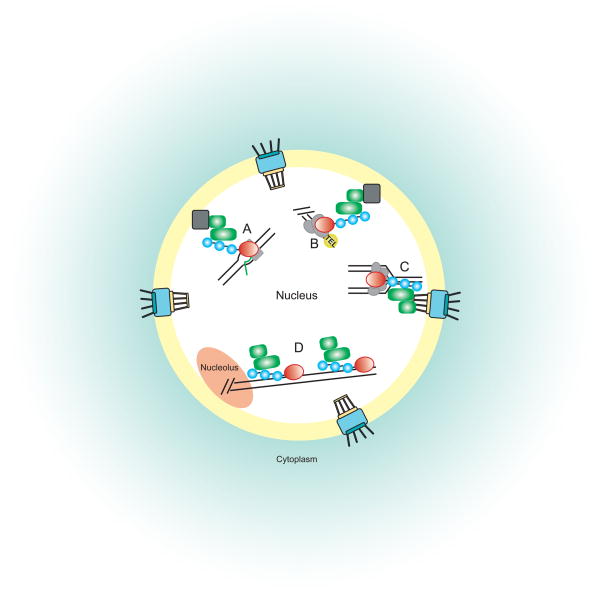

In yeast, STUbLs appear to be restricted to the nucleus.18–23 In contrast, both nuclear and cytoplasmic localization is seen in humans and flies24,25, although functions thus far ascribed to STUbLs place their primary role in the maintenance of chromatin function. How nuclear localization is established and whether there is shuttling or regulation of the enzymes remain open questions. Some of the known and potential functions of STUbLs in the nucleus and at the nuclear membrane are illustrated in Fig. 2, and are discussed below.

Figure 2.

STUbL roles in chromatin function. STUbL (green) binds sumoylated (blue) substrates (red) to contribute to maintenance and regulation of chromatin and responses to sources of genotoxic insult. For simplicity, ubiquitination of STUbL substrates is omitted in cartoon. A. STUbL functions as a transcriptional coactivator. B. STUbL localizes to the nuclear periphery where it functions in telomeric maintenance by interaction with SIR and YKU proteins. C. STUbL facilitates immobilizing double-strand DNA breaks to the nuclear pore. D. STUbL may be involved in other chromatin functions like rDNA repair and recovery from replication fork arrest. Gray boxes indicate factors of the nuclear envelope that may contribute to STUbL targeting. Baskets indicate nuclear pore complexes.

STUbLs in budding yeast

There are two STUbLs in budding yeast, Slx and Uls1.26 More progress has been made in understanding the importance of Slx STUbL in nuclear functions yet future studies determining ULS1 roles in chromatin maintenance are expected to be as significant.

The SLX STUbLs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S.c.) were first discovered in a screen designed to identify genes that are synthetic lethal in combination with disruption of SGS1, the gene encoding the conserved antirecombinogenic RecQ DNA helicase. Combining mutations in SLX5 or SLX8 with sgs1 Δ results in cell death.27 This revealed that STUbLs played a role in genome stability. Other aspects of chromatin function were compromised in slx STUbL mutants, which included telomeric and rDNA silencing defects19,28, DNA damage agent sensitivity18, susceptibility to gross chromosomal rearrangements23,29,30, and sub-optimal growth. Sumoylated proteins accumulate in slx mutants26, providing evidence of its role in regulating sumoylated substrate levels. As with other SUMO pathway mutants, slx mutants develop a nibbled colony morphology and accumulate high but variable levels of the naturally occurring 2-micron plasmid.28,31 In slx mutants, increased levels of sumoylated Flp1 recombinase are observed.31 This enzyme is encoded on the 2-micron plasmid and contributes to the STUbL mutants’ growth defects, because when the plasmid is cured from the mutants the cells no longer form nibbled colonies. slx STUbL mutants also exacerbate premature aging in cells lacking the template RNA for telomerase activity.32

Biochemical characterization of the Slx STUbL has been important in its classification as an E3 ubiquitin ligase. In vitro assays revealed that the Slx STUbL formed a heterodimer.22 Like some other heterodimeric E3 RING ubiquitin ligases, only one of the RING domains has E3 activity, in this case Slx8.33 Its E3 ligase activity in vivo is dependent on the ability of Slx5 to interact with substrates via its SIMs. In vivo and in vitro work has identified Ubc4 as the cognate E2 conjugating enzyme.34,35 An interesting note is that Ubc4 acts with a number of E3 ubiquitin ligases in vivo36 and is involved in the turnover of short-lived proteins, especially important in the presence of heat and other stresses. In the presence of heterodimeric E2 Ubc13-Mms2, the Slx STUbL stimulated the formation of Lys-63 ubiquitin chains in vitro35, a linkage found in DNA damage repair pathways (reviewed in 37). The subnuclear location of Slx STUbL may influence the type of ubiquitin linkage it builds. Future in vivo studies will help illuminate this important question that to date has been primarily addressed in vitro.

Multiple yeast two-hybrid experiments identify Uls1, as both a sumoylated protein and a SIM-containing protein.4,38,39 Uls1 is a member of the SWI/SNF family of DNA-dependent ATPases, and shares characteristics of STUbLs by its ability to bind SUMO and sumoylated substrates and for its RING domain. Like the SLX STUbL, ULS1 has connections to the DNA damage response and chromatin functions. Unlike the slx synthetic lethal interaction with sgs1, mutation of ULS1 suppresses sgs1 DNA damage agent sensitivity, and mutations within the ATPase domain of ULS1 mimic the null phenotype.40 Another aspect of Uls1 function was uncovered when strains lacking other SWI/SNF family members RAD51 and RAD54 were challenged with DNA damage agents: viability was dependent on ULS1.41

Originally identified in a screen for factors influencing cryptic mating type loci silencing, high levels of ULS1 result in the derepression of the normally silenced HMR locus.42 Further investigation revealed that Uls1 functions in mating type switching, and its N-terminus interacts with the silencing protein Sir4 by two-hybrid analysis. There is evidence that Uls1 localizes to both the nucleoplasm and the nucleolus.20 A two-hybrid interaction observed between SIMs of Uls1 and the ribosomal assembly protein Ebp2 required SUMO modification of Ebp2, although the biological significance of this interaction is not understood.20 Uls1 has been shown to interact in vitro with Ubc4, however evidence of its E3 ligase activity has not been demonstrated in vivo or in vitro as has been shown with the Slx STUbL.26 Much less is known about Uls1 but the large, multidomain protein may be a nexus in multiple aspects of chromatin biology.

STUbLs in fission yeast

Interestingly, the single gene encoding SUMO (PMT3) is not essential to Schizosaccharomyces pombe (S.p)43, yet fission yeast mutants lacking Pmt3 and STUbL genes are sensitive to DNA damaging agents.44 The S.p. proteins Rfp1 and Rfp2 are functionally similar to S.c. Slx5, and are involved in substrate binding and heterodimerize with Slx8.45 Rfp1 was discovered by its ability to interact with the DNA checkpoint kinase Chk1.46 Disruption of both genes rfp1 and rfp2 show the characteristic STUbL mutant phenotypes of slow growth, DNA damage sensitivity and sumoylated protein accumulation.21,44 In contrast, SUMO protease Ulp2 overexpression reverses these phenotypes, suggesting that the dynamic balance of polysumoylated proteins is critical.46

Fly Degringolade

The sole STUbL homolog Degringolade (Dgrn) in Drosophila was identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen to find factors that interact with the transcriptional repressor Hairy.47 Dgrn contains the canonical RING and SIM domains that define the STUbL family of E3 ubiquitin ligases. Hairy and similar repressors were targets of Dgrn ubiquitination in an in vitro reconstituted assay.24,48 Since no partners of Dgrn have yet been established, whether or not it functions as a homodimer or heterodimer remains to be determined.

Degringolade has a role in transcriptional coactivation, and takes part in regulating key processes in embryogenesis.24,48 In fact, embryos produced from a dgrn null mutant typically arrest after two or three nuclear divisions. This rapid deterioration seen in dgrn embryos was the reasoning for its name that means “to tumble out of control” (personal communication, S.M. Parkhurst). Mutant embryos also accumulate polysumoylated proteins as seen in STUbL mutants from other species.24,48

Vertebrate RNF4

As in Drosophila, there is only one STUbL identified in vertebrates to date, named RNF4 (for Really Interesting New Gene Finger Protein 4 and previously known also as SNURF, for Small Nuclear RING Finger).49,50 Unlike the yeast Slx STUbL, RNF4 appears to function as a homodimer.51 It combines the features of Slx5 SIMs with the functional Slx8 RING domain in one protein. RNF4 is highly conserved in vertebrates, having 91% identity between mouse and human orthologs.49,50

RNF4 cross-species complementation of the slx STUbL was tested, and indeed, expression of RNF4 in S.c. slx STUbL mutants reverses DNA damage sensitivity, sumoylation accumulation, and suppresses the synthetic lethality of slx sgs1 mutants52, thereby underscoring the fundamental conservation of this biochemical activity. RNF4 was first identified as a transcriptional coactivator, however, it is now known that it has diverse functions, noted below.

Effects on genome stability in yeast

Early results demonstrated that mutants for genes encoding STUbLs were sensitive to DNA damage, interpreted as underlying functions in the maintenance of genome stability. One method to detect DNA damage is the visualization of Rad52 foci at DNA breaks, which increase as an indicator of damage. Slx STUbL subunits are detected in these foci, and in their absence, the incidence and persistence of the Rad52 foci is elevated.18 Nagai and colleagues examined budding yeast strains in which a double strand (ds) DNA break event could be induced but not repaired. Visualization of this break showed that it becomes tethered to the nuclear pores. Attachment of the damaged site to the nuclear membrane was dependent on nucleoporins and Slx5 and Slx8.23 Intriguingly, a separate study indicated that sumoylated S.c. Htz1, a histone H2A variant, colocalized to the nuclear membrane, apparently to confine a ds DNA break.53,54 Multiple nuclear pore proteins are sumoylated, and they along with sumoylated Htz1, may be targets of STUbL action, or serve as anchors that interact with the SIMs of STUbL so that it may be properly localized to target other proteins (reviewed in 55).

Slx STUbL colocalization with some Rad52 DNA damage foci may also implicate its involvement in rDNA homologous recombination repair.53 Sumoylation of S.c. Rad52 influences its exit from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm where repair occurs. Localization of Slx5 and Slx8 do not overlap extensively with nucleolar staining, but higher resolution studies, including under conditions of genotoxic stress or high recombination will be valuable, for elucidating STUbL in nucleolar roles.

Analysis of TDP1, the gene encoding tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I, suggest one way by which potentially lethal Top1-DNA adducts produced in the course of replication are resolved. The tdp1Δ mutant in combination with the slx8-1 mutation in S. pombe revealed that STUbL contributes to resolution of the toxic adducts.56 The tdp1Δ cells have severe negative genetic effects with slx5 Δ and slx8Δ as determined by Synthetic Genetic Array analysis in budding yeast56,57, indicating another conserved STUbL role. Budding yeast Slx8 has also been shown to colocalize with the PCNA clamp in DNA replication centers.28. Thus it appears that both the catalytic activity and regulated localization contribute to STUbL functions in responding to DNA damage and stabilizing the genome.

STUbLs in development and disease

As noted above, early yeast studies suggested that polysumoylated protein accumulation is toxic to the cell. Strains disrupted in genes encoding STUbLs and SUMO proteases share defects in chromatin function and optimal growth. The downstream effects of polysumoylated substrates are expected to be diverse. If there are more sumoylated proteins, the SIM-containing proteins may accumulate as well, with the possibility of becoming sequestered, and indirectly compromising their functions.

In contrast, new studies reveal that polysumoylation may not always be a toxic trigger. Specifically, it was discovered in S.c. that mutation or deletion of the SUMO protease ULP2 suppressed the synthetic lethality of slx sgs1.52 However, under the suppressing conditions, the level of polysumoylated proteins observed was greater than either ulp2Δ or slxΔ mutant alone. One potential explanation for these results is that when SGS1 is not present, SLX STUbL activity is required, but not necessarily for promoting degradation. By decreasing or eliminating the protease activity encoded by ULP2, one or multiple substrates may remain sumoylated, and be thereby at least partially functional. STUbL mutant growth on DNA damage agents hydroxyurea and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) is not affected by loss of ULP2 however, not yet addressed is if other chromatin function defects are suppressed in mutants defective in STUbL and ULP2.52

Examination of STUbL function in Drosophila has been informative. Degringolade was identified as a coactivator of key repressor bHLH proteins.24,48 Important developmental programs are misregulated in Dgrn mutants lacking an intact RING domain and SIMs, and also result in a striking phenotype whereby nuclear membrane formation occurred to encase individual chromosomes instead of forming a single nucleus.48 Like yeast, STUbL localization to the nuclear membrane may be a shared feature required for proper fly nuclear architecture.

Degringolade and RNF4 have significant roles in transcriptional activation25,49,58–67. Comparable evidence is not yet available for yeast STUbL-mediated transcriptional regulation. However, it is known that in S.c. yeast, the MATα2 transcriptional repressor for maintaining the mating-type alpha haploid genetic program is stabilized in slx mutants.34 Further, SUMO has been shown to localize to promoters of constitutive and inducible genes in yeast68, and the SUMO protease mutant ulp2Δ interferes with the inositol synthesis pathway69. Future studies will distinguish the relative contribution of SUMO itself versus sumoylated proteins to gene regulation, and if STUbLs are indeed required for global transcriptional regulation in yeast. Considering that the proteasome is recruited to DNA damage foci and to transcribed genes70,71, where it may have both proteolytic and non-proteolytic functions, modification by STUbL may prove to bridge the interaction between the proteasome and transcription activators or DNA damage response proteins.

Loss of RNF4 function is associated with embryonic lethality and elevated levels of global DNA methylation.72 Deamination of 5-methylcytosine can contribute to introduce genetic instability and, it has been proposed that demethylation serves as a DNA repair process for the correction of G:T mismatches by base excision. Indeed cells lacking RNF4 have higher levels of DNA damage.72 The activities of mismatch processing enzymes TDG and APE1 increase in the presence of RNF4. The ability of the mismatch enzymes to bind RNF4 do not depend on the RING or SIMs of RNF4. How RNF4 might stimulate TDG and APE1 activities remains to be determined. Authors of the work proposed that RNF4 functions as a scaffold, which shares the roles STUbLs play in yeast in response to ds DNA damage. It remains an attractive possibility that DNA methylating enzymes are targets of RNF4 modification.

A specific connection of STUbL activity to human disease comes through the leukemia-associated translocation chimera PML-RAR. The PML (Promyelocytic Leukemia) protein itself is required for PML nuclear body formation, as is its sumoylation.73 PML nuclear bodies are composed of many nuclear proteins that are implicated in a variety of processes including DNA damage repair, gene transcription, apoptosis, and viral infection response (reviewed in 74). PML has been proposed to negatively regulate some DNA repair pathways, and PML nuclear body formation is disrupted in cells expressing the chimeric PML-RAR protein.75

A particularly intriguing aspect of STUbL regulation comes from the details of how the therapeutic agent arsenic trioxide (ATO) mediates its effects on PML-RAR.76–79. The studies addressing ATO action have provided insight into STUbL action, and highlight the importance of its function. Both the normal PML and PML-RAR are substrates of RNF4-mediated degradation. How a degradation pathway can be manipulated in the treatment of disease is exemplified by ATO-induced degradation. PML-RAR oligomerizes when arsenic binds cysteines of its zinc fingers, thus enhancing the ability for the E2 SUMO conjugating enzyme UBC9 to bind and sumoylate PML.80 SUMO chains mediate binding between the SIMs of RNF4 and the chimera, to promote RNF4 addition of K48-linked ubiquitin chains to the substrate to be degraded by the 26S proteasome.2,77,78

Strategies for substrate identification

Many genome-scale proteomic studies have been successfully applied in defining the repertoire of proteins in specific organisms that are sumoylated or ubiquitinated. These have been important first steps for subsequent analyses directed at validating the substrates, mapping the sites of modification, and determining the functional significance of the modification through site-directed mutagenesis. To date, only a limited number of STUbL substrates have been characterized (Table 1).

Table 1.

Known and potential STUbL substrates

| Substrates | Function | Evidence | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Slx5/Slx8 | |||

| Mot1 | TATA binding protein regulation | Canavanine-induced degradation blocked in STUbL mutant | 90 |

| Spt20 | SAGA coactivator complex member | Canavanine-induced degradation blocked in STUbL mutant | 90 |

| MATα1 | mating-type specific gene expression | Slowed degradation in STUbL mutant; in vivo and in vitro STUbL-dependent ubiquitination | 91 |

| MATα2 | haploid-specific transcriptional repression | Slowed degradation and higher steady state levels in STUbL mutant | 34 |

| Flp1 | 2-micron plasmid propagation | Accumulation of polysumoylated Flp1 in STUbL mutants | 31 |

| Rad52 & Rad57 | double-strand DNA break repair | In vitro STUbL-dependent ubiquitination | 35 |

|

| |||

| Fly Dgrn | |||

| Hairy | transcriptional corepressor in development | In vitro STUbL-dependent ubiquitination | 24,48 |

|

| |||

| Human RNF4 | |||

| PML | PML nuclear body formation | In vitro STUbL-dependent ubiquitination; in vivo stabilization with RNF4 siRNA | 77–79 |

| PML-RAR | disruption in PML nuclear body formation and in hematopoietic progenitor cell differentiation | Arsenic-induced degradation blocked in RNF4 dominant negative mutant | 78,79 |

| PEA3 | transcription factor in development | PEA3 ubiquitination lowered with RNF4 siRNA | 92 |

| PARP1 | DNA damage response | In vivo STUbL-dependent ubiquitination and lower steady state levels | 93 |

| HIF2α | hypoxia-inducible transcription factor | Accumulation of polysumoylated HIF2α with RNF4 shRNA | 94 |

| CENP-I | kinetochore assembly | Accumulation of unmodified CENP-I with RNF4 siRNA | 95 |

| SP1 | transcription factor in development | In vivo and in vitro STUbL-dependent ubiquitination | 96 |

| Tax | disruption in DNA damage response | In vivo and in vitro STUbL-dependent ubiquitination | 81 |

| MDC1 | DNA damage response | In vivo and in vitro STUbL-dependent ubiquitination; accumulation of MDC1 with RNF4 siRNA; SUMO2-dependent interaction | 97–99 |

The modification of mass proteomic strategies that have been integral in the identification of sumoylated proteins will be valuable tools for identifying the full set of STUbL substrates. However, the analysis will likely be complex. What has become apparent from the study of sumoylated proteins modified by STUbL is that only a small fraction of a substrate may be sumoylated at a given time, and its ubiquitination by STUbLs will be an even smaller portion of the sumoylated pool. The important work demonstrating how PML and PML-RAR ubiquitination by STUbL leads to their degradation, serves as a clear example of STUbL-dependent degradation but may only represent how a minority of STUbL substrates are regulated.

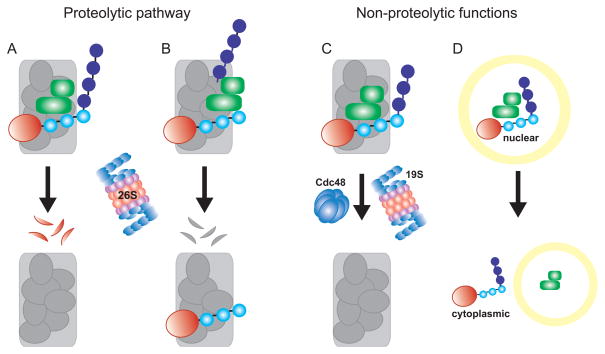

In fact, STUbL regulation of substrates appears complicated and varied. There are substrates regulated by STUbL that are not sumoylated. In contrast others are modified by STUbL but are not degraded. For example, the yeast MATα2 is stabilized in slx mutants without prior SUMO modification.34 Likewise, Dgrn ubiquitinates the repressor Hairy to prevent corepressor interaction and it also sequesters the sumoylated corepressor, without any apparent affect on stability of either protein.24 Furthermore, the Human T-cell Leukemia virus Type 1 oncoprotein Tax is modified by RNF4, but instead of effecting its degradation, the nuclear protein translocates to the cytoplasm.81 Figure 3 illustrates how STUbLs may influence the regulation of chromatin factors and complexes in both proteolytic and non-proteolytic pathways.

Figure 3.

Possible fates of STUbL substrates. (A and B) STUbL (green) binds sumoylated substrate (red with blue SUMO chain) in complex with other proteins. Sumoylated substraten (red) in A or complex member (gray) in B becomes ubiquitinated by STUbL. Ubiquitination leads to targeting and degradation by the 26S proteasome (Red and gray flecks represent degraded substrates), which may or may not influence whole complex stability (not shown). (C) Ubiquitination of sumoylated substrate by STUbL leads to a non-proteolytic signal. The substrate may be removed by ATPases such as Cdc48 or the 19S lid of the 26S proteasome, or recruit other nuclear factors (not shown). (D) STUbL ubiquitination of sumoylated substrate leads to a change in substrate location.

Understanding SUMO dynamics in response to different stresses may bring insight to their regulation by STUbLs. Cellular stresses like alcohol, heat, and proteasome inhibition, induce global sumoylation.9–11,79,82 How these different cellular stress conditions affect STUbL localization may also help identify its substrates. The SUMO pathway protease S.c. Ulp1 translocates from the nuclear pore to the nucleous with alcohol exposure.83 Considering the prominent role that STUbLs have in genomic stability, incorporating DNA damage agent exposure both acutely and chronically may help uncover STUbL substrates. Recent work in which Cremona and colleagues marched through screening the sumoylation status of over 179 candidate DNA damage response proteins purified from yeast exposed to the DNA damage agent MMS84, will surely be a valuable source for potential STUbL candidates.

Humanizing yeast for drug discovery

RNF4 has relatively weak sequence similarity to Slx8. In fact, there are four other known or predicted yeast E3 ligases with greater shared similarity to RNF4 than Slx8. Nonetheless, in cross-species complementation experiments, RNF4 expression complements slx5Δ/slx8Δ mutant phenotypes.26 Further evidence for deep functional conservation of the STUbLs comes from similar experiments demonstrating complementation of S. pombe STUbL mutant phenotypes by RNF4.21,44 That the complementation observed can proceed through turnover of sumoylated proteins was shown through analysis of both whole cell lysates and with heterologous expression of PML.79

These RNF4- expression experiments thus raise the possibility of another case in which S. cerevisiae can be ‘humanized’ to study molecular mechanisms and genetics important for human disease. Striking precedents exist for analysis of human cancer-related genes such as P53 and BCL2 in yeast.85,86 Similarly, yeast has been used to study human allelic variants of genes with functions in multi-drug transport and metabolic disease with a goal of optimizing therapeutic outcomes (for a few recent examples, 87–89).

It is to be expected that parallel strategies can be developed for identifying enhancers and inhibitors of RNF4-mediated degradation of PML and PLM-RAR in yeast-based screens. Pursuing the significant observations of ATO-enhanced degradation, potentially less toxic but comparably effective compounds may be found. As even more substrates of STUbL are defined, such screens may provide a first, fast and economical approach for identifying molecules of potential therapeutic value. Because of the wide-range of development- and disease- associations in vertebrates with altered RNF4 expression, taking advantage of its functional conservation through study of small molecule and natural-products modulators in yeast should lead to important mechanistic insights and potential clinical significance.90–99

Acknowledgments

The authors thank current and previous lab members for helpful suggestions, with special thanks to C. Chang and S. Gilmore for comments on this manuscript. Our laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Health (L.P. - GM54778, GM090177 and R.M.G. - F32-GM089101).

References

- 1.Perry JJ, Tainer JA, Boddy MN. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Praefcke GJ, Hofmann K, Dohmen RJ. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wohlschlegel JA, Johnson ES, Reed SI, Yates JR., 3rd J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45662–45668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannich JT, Lewis A, Kroetz MB, Li SJ, Heide H, Emili A, Hochstrasser M. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4102–4110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panse VG, Hardeland U, Werner T, Kuster B, Hurt E. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41346–41351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makhnevych T, Sydorskyy Y, Xin X, Srikumar T, Vizeacoumar FJ, Jeram SM, Li Z, Bahr S, Andrews BJ, Boone C, Raught B. Mol Cell. 2009;33:124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denison C, Rudner AD, Gerber SA, Bakalarski CE, Moazed D, Gygi SP. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:246–254. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400154-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wykoff DD, O’Shea EK. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:73–83. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400166-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatham MH, Matic I, Mann M, Hay RT. Sci Signal. 2011;4:rs4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruderer R, Tatham MH, Plechanovova A, Matic I, Garg AK, Hay RT. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:142–148. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schimmel J, Larsen KM, Matic I, van Hagen M, Cox J, Mann M, Andersen JS, Vertegaal AC. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2107–2122. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800025-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson ES. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:355–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melchior F. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:591–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miteva M, Keusekotten K, Hofmann K, Praefcke GJ, Dohmen RJ. Subcell Biochem. 2010;54:195–214. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6676-6_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hecker CM, Rabiller M, Haglund K, Bayer P, Dikic I. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16117–16127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma Q, Gao X, Cao J, Liu Z, Jin C, Ren J, Xue Y. 2009 submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogt B, Hofmann K. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;832:249–261. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-474-2_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook CE, Hochstrasser M, Kerscher O. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1080–1089. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.7.8123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darst RP, Garcia SN, Koch MR, Pillus L. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1361–1372. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01291-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirai C, Mizuta K. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:1881–1886. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun H, Leverson JD, Hunter T. Embo J. 2007;26:4102–4112. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L, Mullen JR, Brill SJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5541–5551. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagai S, Dubrana K, Tsai-Pflugfelder M, Davidson MB, Roberts TM, Brown GW, Varela E, Hediger F, Gasser SM, Krogan NJ. Science. 2008;322:597–602. doi: 10.1126/science.1162790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abed M, Barry KC, Kenyagin D, Koltun B, Phippen TM, Delrow JJ, Parkhurst SM, Orian A. Embo J. 2011;30:1289–1301. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galili N, Nayak S, Epstein JA, Buck CA. Dev Dyn. 2000;218:102–111. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200005)218:1<102::AID-DVDY9>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uzunova K, Gottsche K, Miteva M, Weisshaar SR, Glanemann C, Schnellhardt M, Niessen M, Scheel H, Hofmann K, Johnson ES, Praefcke GJ, Dohmen RJ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34167–34175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullen JR, Kaliraman V, Ibrahim SS, Brill SJ. Genetics. 2001;157:103–118. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess RC, Rahman S, Lisby M, Rothstein R, Zhao X. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6153–6162. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00787-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Putnam CD, Hayes TK, Kolodner RD. Nature. 2009;460:984–989. doi: 10.1038/nature08217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C, Roberts TM, Yang J, Desai R, Brown GW. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiong L, Chen XL, Silver HR, Ahmed NT, Johnson ES. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1241–1251. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azam M, Lee JY, Abraham V, Chanoux R, Schoenly KA, Johnson FB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:506–516. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie Y, Kerscher O, Kroetz MB, McConchie HF, Sung P, Hochstrasser M. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34176–34184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie Y, Rubenstein EM, Matt T, Hochstrasser M. Genes Dev. 2010;24:893–903. doi: 10.1101/gad.1906510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ii T, Fung J, Mullen JR, Brill SJ. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2800–2809. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.22.4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoll KE, Brzovic PS, Davis TN, Klevit RE. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15165–15170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.203968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Hakim A, Escribano-Diaz C, Landry MC, O’Donnell L, Panier S, Szilard RK, Durocher D. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parnas O, Amishay R, Liefshitz B, Zipin-Roitman A, Kupiec M. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2894–2903. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.17.16778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bialkowska A, Kurlandzka A. Yeast. 2002;19:1323–1333. doi: 10.1002/yea.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cal-Bakowska M, Litwin I, Bocer T, Wysocki R, Dziadkowiec D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:8765–8777. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah PP, Zheng X, Epshtein A, Carey JN, Bishop DK, Klein HL. Mol Cell. 2010;39:862–872. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Z, Buchman AR. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5461–5472. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka K, Nishide J, Okazaki K, Kato H, Niwa O, Nakagawa T, Matsuda H, Kawamukai M, Murakami Y. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8660–8672. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prudden J, Perry JJ, Nie M, Vashisht AA, Arvai AS, Hitomi C, Guenther G, Wohlschlegel JA, Tainer JA, Boddy MN. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2299–2310. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05188-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prudden J, Pebernard S, Raffa G, Slavin DA, Perry JJ, Tainer JA, McGowan CH, Boddy MN. Embo J. 2007;26:4089–4101. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kosoy A, Calonge TM, Outwin EA, O’Connell MJ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20388–20394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poortinga G, Watanabe M, Parkhurst SM. Embo J. 1998;17:2067–2078. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barry KC, Abed M, Kenyagin D, Werwie TR, Boico O, Orian A, Parkhurst SM. Development. 2011;138:1759–1769. doi: 10.1242/dev.058420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moilanen AM, Poukka H, Karvonen U, Hakli M, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5128–5139. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiariotti L, Benvenuto G, Fedele M, Santoro M, Simeone A, Fusco A, Bruni CB. Genomics. 1998;47:258–265. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liew CW, Sun H, Hunter T, Day CL. Biochem J. 2010;431:23–29. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mullen JR, Das M, Brill SJ. Genetics. 2011;187:73–87. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.124347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres-Rosell J, Sunjevaric I, De Piccoli G, Sacher M, Eckert-Boulet N, Reid R, Jentsch S, Rothstein R, Aragon L, Lisby M. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:923–931. doi: 10.1038/ncb1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalocsay M, Hiller NJ, Jentsch S. Mol Cell. 2009;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagai S, Davoodi N, Gasser SM. Cell Res. 2011;21:474–485. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heideker J, Prudden J, Perry JJ, Tainer JA, Boddy MN. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collins SR, Miller KM, Maas NL, Roguev A, Fillingham J, Chu CS, Schuldiner M, Gebbia M, Recht J, Shales M, Ding H, Xu H, Han J, Ingvarsdottir K, Cheng B, Andrews B, Boone C, Berger SL, Hieter P, Zhang Z, Brown GW, Ingles CJ, Emili A, Allis CD, Toczyski DP, Weissman JS, Greenblatt JF, Krogan NJ. Nature. 2007;446:806–810. doi: 10.1038/nature05649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pero R, Lembo F, Palmieri EA, Vitiello C, Fedele M, Fusco A, Bruni CB, Chiariotti L. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3280–3285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fedele M, Benvenuto G, Pero R, Majello B, Battista S, Lembo F, Vollono E, Day PM, Santoro M, Lania L, Bruni CB, Fusco A, Chiariotti L. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7894–7901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaiser FJ, Moroy T, Chang GT, Horsthemke B, Ludecke HJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38780–38785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poukka H, Aarnisalo P, Santti H, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:571–579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poukka H, Karvonen U, Yoshikawa N, Tanaka H, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 17):2991–3001. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pero R, Lembo F, Di Vizio D, Boccia A, Chieffi P, Fedele M, Pierantoni GM, Rossi P, Iuliano R, Santoro M, Viglietto G, Bruni CB, Fusco A, Chiariotti L. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1225–1230. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62508-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salonen J, Butzow R, Palvimo JJ, Heikinheimo M, Heikinheimo O. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;307:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saville B, Poukka H, Wormke M, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ, Stoner M, Samudio I, Safe S. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2485–2497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lyngso C, Bouteiller G, Damgaard CK, Ryom D, Sanchez-Munoz S, Norby PL, Bonven BJ, Jorgensen P. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26144–26149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hirvonen-Santti SJ, Rannikko A, Santti H, Savolainen S, Nyberg M, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ. Eur Urol. 2003;44:742–747. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00382-8. discussion 747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosonina E, Duncan SM, Manley JL. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1242–1252. doi: 10.1101/gad.1917910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Felberbaum R, Wilson NR, Cheng D, Peng J, Hochstrasser M. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:64–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05878-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Geng F, Tansey WP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsolou A, Nelson G, Trachana V, Chondrogianni N, Saretzki G, von Zglinicki T, Gonos ES. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:432–442. doi: 10.1002/iub.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hu XV, Rodrigues TM, Tao H, Baker RK, Miraglia L, Orth AP, Lyons GE, Schultz PG, Wu X. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15087–15092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009025107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muller S, Matunis MJ, Dejean A. Embo J. 1998;17:61–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lallemand-Breitenbach V, de The H. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000661. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhu J, Koken MH, Quignon F, Chelbi-Alix MK, Degos L, Wang ZY, Chen Z, de The H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3978–3983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Geoffroy MC, Jaffray EG, Walker KJ, Hay RT. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;21:4227–4239. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-05-0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lallemand-Breitenbach V, Jeanne M, Benhenda S, Nasr R, Lei M, Peres L, Zhou J, Zhu J, Raught B, de The H. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:547–555. doi: 10.1038/ncb1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tatham MH, Geoffroy MC, Shen L, Plechanovova A, Hattersley N, Jaffray EG, Palvimo JJ, Hay RT. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:538–546. doi: 10.1038/ncb1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weisshaar SR, Keusekotten K, Krause A, Horst C, Springer HM, Gottsche K, Dohmen RJ, Praefcke GJ. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3174–3178. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang XW, Yan XJ, Zhou ZR, Yang FF, Wu ZY, Sun HB, Liang WX, Song AX, Lallemand-Breitenbach V, Jeanne M, Zhang QY, Yang HY, Huang QH, Zhou GB, Tong JH, Zhang Y, Wu JH, Hu HY, de The H, Chen SJ, Chen Z. Science. 2010;328:240–243. doi: 10.1126/science.1183424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fryrear KA, Guo X, Kerscher O, Semmes OJ. Blood. 2012;119:1173–1181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-358564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhou W, Ryan JJ, Zhou H. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32262–32268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404173200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sydorskyy Y, Srikumar T, Jeram SM, Wheaton S, Vizeacoumar FJ, Makhnevych T, Chong YT, Gingras AC, Raught B. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4452–4462. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00335-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cremona CA, Sarangi P, Yang Y, Hang LE, Rahman S, Zhao X. Mol Cell. 2012;45:422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kobayashi T, Wang T, Qian H, Brachmann RK. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;223:73. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-329-1:73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Silva RD, Manon S, Goncalves J, Saraiva L, Corte-Real M. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:246–255. doi: 10.2174/138161211795049651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jeong H, Herskowitz I, Kroetz DL, Rine J. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e39. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marini NJ, Gin J, Ziegle J, Keho KH, Ginzinger D, Gilbert DA, Rine J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8055–8060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802813105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mayfield JA, Davies MW, Dimster-Denk D, Pleskac N, McCarthy S, Boydston EA, Fink L, Lin XX, Narain AS, Meighan M, Rine J. Genetics. 2012;190:1309–1323. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang Z, Prelich G. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1694–1706. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01470-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nixon CE, Wilcox AJ, Laney JD. Genetics. 2010;185:497–511. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.115907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Guo B, Sharrocks AD. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3204–3218. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01128-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martin N, Schwamborn K, Schreiber V, Werner A, Guillier C, Zhang XD, Bischof O, Seeler JS, Dejean A. Embo J. 2009;28:3534–3548. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van Hagen M, Overmeer RM, Abolvardi SS, Vertegaal AC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1922–1931. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mukhopadhyay D, Arnaoutov A, Dasso M. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:681–692. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang YT, Yang WB, Chang WC, Hung JJ. J Mol Biol. 2011;414:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Luo K, Zhang H, Wang L, Yuan J, Lou Z. Embo J. 2012;31:3008–3019. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Galanty Y, Belotserkovskaya R, Coates J, Jackson SP. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1179–1195. doi: 10.1101/gad.188284.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yin Y, Seifert A, Chua JS, Maure JF, Golebiowski F, Hay RT. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1196–1208. doi: 10.1101/gad.189274.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]