Abstract

Regulation of Notch signaling is critical to development and maintenance of most eukaryotic organisms. The Notch receptors and ligands are integral membrane proteins and direct cell–cell interactions are needed to activate signaling. Ligand-expressing cells activate Notch signaling through an unusual mechanism involving Notch proteolysis to release the intracellular domain from the membrane, allowing the Notch receptor to function directly as the downstream signal transducer. In the absence of ligand, the Notch receptor is maintained in an autoinhibited, protease resistant state. Genetic studies suggest that Notch ligands require ubiquitylation, epsin endocytic adaptors and dynamin-dependent endocytosis for signaling activity. Here we discuss potential models and supporting evidence to account for the absolute requirement for ligand endocytosis to activate signaling in Notch cells. Specifically, we focus on a role for ligand-mediated endocytic force to unfold Notch, override the autoinhibited state, and activate proteolysis to direct Notch-specific cellular responses.

Keywords: Notch, DSL ligands, ADAM10, Endocytosis, Mechanical force, Signaling

1. Introduction

The Notch pathway is a highly conserved signaling system used extensively throughout embryonic development that continues to function in the maintenance of tissues and stem cells in adults [1,2]. Notch signaling is linked to genetic disorders and cancer and recent studies have identified Notch as a potential therapeutic target [3]. Defining the mechanistic basis of ligand-induced Notch signaling is critical to the design of successful therapies. The integral membrane nature of Notch pathway receptors and canonical ligands provides a mechanism for cells to directly interact and communicate with each other. The ligand transmembrane structure also facilitates endocytosis, which is absolutely required for ligand cells to activate signaling in contacted Notch cells [4–6]. The proposal that ligands on the surface of a signal-sending cell must be internalized to activate a receptor on the signal-receiving cell represents a novel role for endocytosis in activation of intercellular signaling.

Notch signaling is mechanistically remarkable in its reliance on ligand endocytosis to promote receptor proteolysis and release the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) that directly participates in downstream signaling [7]. In the majority of cellular responses, NICD released from the membrane moves to the nucleus and interacts with the major downstream effector, CSL pre-bound to Notch target genes, to recruit co-factors for transcriptional activation [8]. NICD generation is dependent on an initial activating proteolytic event within the Notch extracellular domain (NECD) at a designated S2 cleavage site close to the extracellular face of the plasma membrane. Two members of the ADAM family of metalloproteases, ADAM10 and ADAM17, are implicated in S2 cleavage of Notch [9–13]. S2 cleavage is considered the rate-determining step in Notch activation because ADAM-mediated removal of inhibitory extracellular sequences is necessary for efficient intramembrane γ-secretase cleavage at the S3 site [14] to release the active NICD signaling fragment.

In addition to these ligand-induced proteolytic cleavage events, Notch is cleaved independent of ligand by a furin-like protease during trafficking to the cell surface [15,16]. Cleavage at the S1 site by furin produces N- and C-terminal fragments that remain stably associated through multiple non-covalent interactions to form the mature heterodimeric receptor [17–19]. Although furin cleavage is highly conserved among the four mammalian Notch receptors [20], Drosophila Notch does not appear to undergo furin processing [21]. In contrast to the convincing biochemical data for furin processing of mammalian Notch, the data supporting Notch heterodimeric formation in flies do not agree [21–24], and thus, this aspect of Notch signaling has remained somewhat unsettled. In fact, the importance of furin cleavage in general has received considerable debate with some arguing that Notch furin processing is a pre-requisite for efficient signaling [15,25], while others purport only a regulatory role in trafficking Notch to the cell surface[16,26].

Despite extensive evidence implicating ligand endocytosis in Notch signaling, the mechanistic basis of this requirement has also remained poorly understood and controversial. Genetic, biochemical, cell biological and structural studies have provided insight into how ligand cells might activate signaling in Notch cells. Here we briefly review the evidence supporting a critical role for ligand endocytosis in activation of Notch signaling. We then discuss proposed models for ligand endocytosis in Notch signaling with a focus on the mechanistic aspects of Notch activation gleaned from high resolution structural studies and recent computational simulations and modeling.

2. Current models for ligand endocytosis in activation of Notch signaling

Early studies with shibire, the Drosophila homolog of dynamin identified the classic Notch neurogenic phenotype [27]. Since dynamin is best known for its role in releasing endocytic vesicles from the plasma membrane [28], this report provided the first evidence that Notch signaling requires endocytosis. Subsequent genetic mosaic analysis with shibire indicated a critical role for dynamin in signal reception by the Notch cell [29], as found for other cellular signaling receptors. What was surprising, however, was the requirement for dynamin by cells expressing the Notch ligand Delta to activate signaling in contacted Notch cells. Additional findings for dynamin-dependent endocytosis by Delta cells to internalize the NECD from cells producing active NICD, offered the first, yet novel, role for ligand endocytosis in regulating Notch proteolysis [30]. Further findings that ligands must be ubiquitylated[31–34] and require epsin endocytic adaptors [35–37] known to direct trafficking of ubiquitylated cargo [38], suggested functional and mechanistic links for ligand endocytosis and recycling in Notch signaling (reviewed in Ref. [39]).

Although paradoxical in nature, a requirement for endocytosis by the signal-sending cell represents an aspect of cellular signaling unique to the Notch pathway. Nonetheless, the exact function ligand endocytosis serves to activate Notch signaling has remained a mystery. Two popular models for ligand endocytosis are (1) prior to Notch binding, endocytosis enables ligand processing and recycling of an active ligand back to the cell surface [6,40] and (2) following ligand binding to Notch, endocytosis by the ligand cell produces mechanical force to pull on Notch and induce structural changes that permit activating proteolysis to release the NICD[4,7]. It is possible, however, that both models account for the absolute requirement for ligand endocytosis, especially if recycling produces a high affinity ligand [41] to secure ligand–Notch interactions and sustain ligand-mediated pulling for activating proteolysis.

3. Ligand recycling in Notch signaling is context dependent and not a general requirement

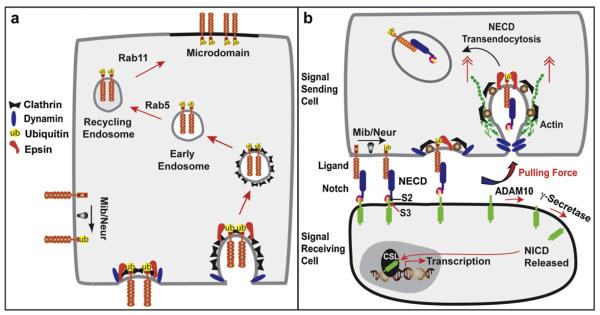

Studies in Drosophila and mammalian cells have suggested signaling activity requires endocytosis for ligand trafficking through the recycling endosome prior to engagement with Notch[36,41–45]. This “recycling” model proposes that ligand delivered to the cell surface is not competent to signal and must be internalized and recycled back to the cell surface, perhaps to a specific microdomain (Fig. 1a), where it can activate Notch on adjacent cells. The major support for this model comes from studies with Drosophila sensory organ precursors (SOPs) and polarized mammalian cells, both of which display complex ligand trafficking proposed to regulate signaling activity [42–45]. Specifically, basal-to-apical ligand trafficking in SOPs requires ubiquitylation, recycling components and actin polymerization to activate signaling and direct cell fate choices regulated by Notch. More recent genetic studies in Drosophila, however, provide evidence that the ligand recycling requirement may be related to a particular cell context. Although, SOP cell fates require the recycling components Rab11 and Sec15 for ligand signaling activity [43,44], neither Rab11 nor Rab5 (which directs access to the Rab11 recycling endosome, Fig. 1a), are required for ligand cells to activate Notch signaling in the germline or developing eye [46,47]. Based on these studies, ligand trafficking through the recycling pathway does not appear to be essential for all Notch-dependent developmental events. These findings provide support for the view that despite being absolutely required for SOP cell fates, ligand recycling is not a general, core requirement for ligand-induced Notch signaling.

Fig. 1.

Models for ligand endocytosis in Notch signaling. (a) The “recycling” model proposes endocytosis promotes recycling of ligand ubiquitylated by the E3 ubiquitin (Ub) ligases Mindbomb (Mib) or Neuralized (Neur). Ub recruites epsin, for clathrin/dynamin-dependent ligand endocytosis and subsequent trafficking via early/recycling endosomes to a cell surface microdomain. (b) The “pulling force” model proposes interactions between ligand signal-sending and Notch signal-receiving cells induce ligand ubiquitylation and formation of epsin-dependent endocytic structures for mechanical force (double red arrowheads) to remove NECD from the intact Notch heterodimer for uptake by ligand cells (NECD transendocytosis). The remaining membrane-bound Notch undergoes activating proteolysis by ADAM at S2 and γ-secretase at S3 to release NICD for translocation to the nucleus and transcription of Notch target genes.

The alternative “pulling force” model incorporates the critical role for ligand endocytosis with Notch structural findings (Fig. 1b). Specifically, mechanical force produced during transendocytosis of the NECD by the ligand cell is proposed to drive proteolytic activation of Notch [30,48]. Here, interactions between ligand and Notch cells are predicted to produce resistance to endocytosis of bound Notch by ligand cells. Based on reported ligand signaling requirements, resistance to ligand endocytosis may stimulate ligand ubiquitylation and allow recruitment of ubiquitin-binding epsin endocytic adaptors [39]. Along with clathrin, dynamin and actin, mechanical force produced by ligand endocytosis could be used to unfold Notch and expose it to activating proteolysis for NICD to direct downstream signaling events. Important to this model, ligand cells defective in endocytosis bind and cluster Notch, yet fail to dissociate or activate Notch [48]. These findings underscore the critical role for ligand endocytosis and indicate that ligand binding alone is not sufficient to activate Notch. Furthermore, dynamin, epsins and actin associated with mechanical force for membrane bending during invagination [49] are also required for ligand signaling activity.

4. Ligand endocytic pulling force to unfold Notch and allow activating proteolysis

4.1. Structural studies provide mechanistic insight into ligand signaling activity

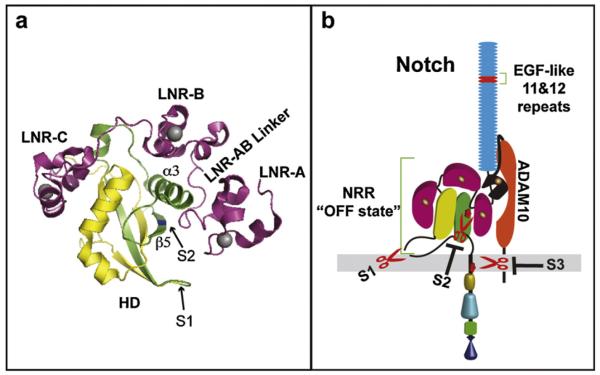

Central to understanding how Notch ligands signal is defining how ADAM cleavage at the S2 site is regulated. Consistent with a rate-limiting role for S2 cleavage in Notch activation, high resolution structural studies indicate that the ADAM cleavage site in Notch is highly protected in the unligated state [50–52]. Specifically, these studies have revealed that the S2 site is buried deep within a highly conserved, structurally compact domain dubbed the negative regulatory region (NRR), composed of three Lin12/Notch repeats (LNR-A-C) and a heterodimerization domain (HD) (Fig. 2a). Structural studies have contributed to deciphering how the NRR might prevent Notch activation in the absence of ligand, and more importantly, how Notch is activated by ligand. Basically, the NRR structure is established independent of furin cleavage [53] and extensive folding of the LNR modules over the HD offers a mechanism to protect the S2 site from ADAM cleavage [8]. Together the findings support a critical role for the NRR in keeping Notch in a protease-resistant state. This idea is also consistent with early structure/function studies in flies and mammalian cells [54–56], which first demonstrated a role for the LNR repeats in preventing Notch activation independent of ligand. More recent sequencing of Notch1 alleles from patients with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) identified the HD as a “hot spot” for activating mutations [57], providing further support for the NRR maintaining Notch in the OFF state (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Structural basis of Notch autoinhibition. (a) Notch1 NRR ribbon diagram (PBD ID: 3ETO) depicting three LNR modules (magenta) with divalent cations (gray) and the HD [HD-N (yellow) and HD-C (green)]. The S2 site (blue) located in β5 is protected from ADAM cleavage by the LNR modules wrapped over the HD. (b) ADAM10 constitutively interacts with intact Notch but the NRR maintains the OFF state in the absence of ligand. The S1 furin cleavage site is located in the unstructured loop and the ligand-binding site composed of EGF-like repeats 11&12 (red) is indicated.

Key to the NRR autoinhibited structure are inter- and intra-domain interactions that anchor the HD alpha helix 3 over the S2 site and produce a long range hydrophobic “plug” composed of a linker region between LNR-A and LNR-B (Fig. 2a). Together with the packing of LNR-A against the HD β5 containing the S2 site, these interactions are predicted to render the S2 scissile bond inaccessible for proteolytic cleavage [8]. Indeed, full Notch activation requires removal of LNR-A, the LNR-AB linker as well as LNR-B [52], supporting the idea that LNR displacement is a pre-requisite for S2 cleavage. Moreover, chelation of divalent cations, required for LNR structural integrity, by EDTA [53], as well as HD destabilizing mutations proposed to displace LNR-HD contacts and destroy NRR tertiary structure, result in significant ligand-independent activation of Notch [17,18,57].

Given the extensive NRR structural interactions proposed to keep Notch autoinhibited, it has been argued that substantial conformational deformations would be necessary to expose the S2 cleavage site and initiate activating Notch proteolysis [52]. However, the Notch ligand-binding domain is not physically close to the NRR (Fig. 2b), and thus, it is hard to see how ligand binding could produce allosteric-based conformational changes sufficient to expose the S2 site. Instead, ligand endocytosis of Notch bound to a neighboring cell offers a mechanism to exert mechanical force on Notch [30,48] to pull the protective LNRs away from the HD and expose the S2 cleavage site [50]. Inherent in this model, Notch ligand–receptor interactions must be strong enough to survive the proposed pulling force. In support of this idea, atomic force microscopy (AFM) adhesion forces for Delta–Notch in the nanoNewton range have been reported [58]. These surprisingly strong AFM measurements likely reflect simultaneous rupture of multimeric interactions formed between cells programmed to express Delta and Notch.

Force-induced conformational changes obtained for the unfolding of the NRR using computational atomic-level simulations and modeling have recently been reported [59]. Though predictive in nature, this analysis has identified a set of sequential and well-defined structural transformations produced during force-induced unfolding of the NRR to expose the S2 site. The initial force-induced unfolding of the NRR is predicted to disengage the LNR modules containing the protective hydrophobic “plug” (Fig. 2a). Predictions from previous NRR structural studies [50,52], suggested LNR unwrapping alone would expose the S2 site to allow productive cleavage, however, the computational approach suggests additional force is required to unravel the S2-containing β5 and fully expose the S2 site [59]. Supporting this idea is the identification of a partially unfolded transient intermediate in which β5 is decoupled from the intact HD. Since dissociation of the HD was found to require additional force and involve two stages, the stability of this intermediate state may facilitate S2 cleavage prior to HD unfolding as predicted from NRR structural studies. Alternatively, the intermediate conformation may promote stable interactions between Notch and the activating protease, but require further force-induced dissociation of the HD to facilitate proteolytic access at the exposed S2 site.

4.2. Distinct NRR conformations function to regulate S2 exposure and productive ADAM cleavage

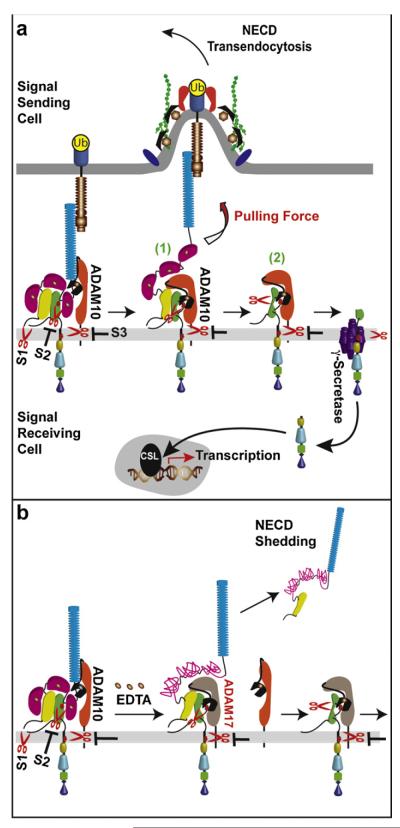

The conformational changes predicted for forced-induced NRR unfolding [59] generally agree with the recent hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry approach designed to detect changes in recombinant NRR structure [53]. Since LNR structural integrity is dependent on divalent cation coordination, chemical chelation induced by EDTA would destabilize the LNR-HD interactions. In fact, hydrogen exchange identified residues exposed during destabilization of the recombinant NRR protein by EDTA. Specifically, residues in and around the S2 site were labeled prior to those associated with HD formation, suggesting S2 exposure occurs before HD unfolding. Based on these findings, the authors conclude that S2 cleavage does not require HD dissociation, however, whether S2 exposure is all that is needed for S2 cleavage remains to be determined. Moreover, the resulting conformational transformations identified for EDTA- and forced-induced NRR unfolding to expose S2 are not identical. For example, force-induced peeling of the LNR modules from the HD involves only minor changes in secondary and tertiary structure. In contrast, EDTA-induced unraveling of the LNRs and disengagement from the HD involves a dramatic loss in structural integrity, likely accounting for EDTA-induce NECD shedding in cell culture studies [18]. Whether these NRR structural differences have mechanistic and/or functional relevance for Notch activation is unclear. Importantly, whether ligand pulling on the Notch heterodimer following cell–cell interactions generates the same NRR unfolding intermediates remains an open question.

Even though NRR unfolding to expose the S2 site is key to Notch activation, distinct conformational intermediates could regulate protease selection, access and/or induce an enzymatic switch for productive S2 cleavage. In this regard, distinct NRR conformational transformations could reflect divergent mechanisms of Notch activation induced by EDTA versus ligand endocytic pulling force. In fact, recent cell culture studies indicate that EDTA activation of Notch is mechanistically distinct from that induced by ligand [9]. Specifically, Notch signaling induced by EDTA requires ADAM17 and cannot be substituted by ADAM10. Conversely, ligand-induced Notch signaling displays an absolute requirement for ADAM10, and importantly, ADAM17 is not required. These findings agree with the Notch loss-of-function phenotypes identified for ADAM10 null mice and flies [12,23,60], and that losses in ADAM17 enzymatic activity directly prevent signaling from the EGF receptor [61] rather than from Notch.

Integrating these biological and structural findings, we propose that distinct NRR structural conformations required to expose the S2 site might also function to select the particular activating protease. Since ADAM17 does not participate in ligand-induced Notch signaling, ligand pulling force might produce distinct conformational changes to promote ADAM10 cleavage of Notch while precluding ADAM17-mediated cleavage (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, EDTA-mediated unraveling of the LNR modules may displace ADAM10 constitutively associated with Notch and favor recruitment of ADAM17 for S2 cleavage independent of ligand (Fig. 3b). Whether NECD-shedding induced by EDTA requires S2 cleavage by ADAM17 or occurs through HD dissociation has yet to be reported.

Fig. 3.

Mechanistic differences between ligand- and EDTA-induced Notch activation. (a) Pulling force generated by endocytosis of Notch-bound ligand peels the LNR modules away from the HD to expose the S2 site, and induces an ADAM10 conformational change for enzymatic activity. ADAM10 cleavage of the exposed S2 directly generates a γ-secretase substrate (1). Alternatively, physical dissociation of the HD within the intact Notch heterodimer generates an inactive intermediate (2), which requires ADAM10 cleavage of the exposed S2 for further activating γ-secretase proteolysis. (b) Activation of Notch by EDTA-induced chelation of divalent cations critical to LNR structure unravels of the LNR modules (magenta-pink lines) for disengagement from the HD to expose S2 (b). Changes in NRR structure may promote ADAM10 dissociation and recruitment of ADAM17 to effect NECD shedding.

The order that S2 exposure and ADAM10 cleavage occur relative to HD dissociation and NECD transendocytosis during ligand-induced activation of Notch is also unknown. Specifically, is HD unfolding required for S2 cleavage or can cleavage occur prior to HD dissociation? According to the proposed “lift-and-cut” model [52], S2 exposure is sufficient for ADAM10 cleavage and occurs independent of HD dissociation. This would allow ADAM cleavage of the intact Notch heterodimer and directly produce a substrate primed for γ-secretase to fully activate Notch (Fig. 3a; 1). S2 cleavage prior to HD dissociation is also compatible with proteolytic activation of a colinear form of Drosophila Notch predicted in the absence of furin processing [21]. Nonetheless, broad-spectrum metalloprotease blockade in coculture assays does not diminish uptake of NECD by ligand cells [48]. This surprising finding suggests that in the absence of ADAM cleavage, NECD can be released through HD dissociation. Furthermore, these findings raise the possibility that NECD is released from the intact heterodimer enzymatically by ADAM cleavage as well as physically by HD dissociation. NECD transendocytosis following physical dissociation may allow ADAM10 to fully engage and productively cleave the exposed S2 site, especially if the intact Notch ectodomain hinders access of the exposed S2 site by the catalytic domain. Additionally, ADAM10 enzymatic activity might be triggered by a protease-substrate conformational rearrangement dependent on HD dissociation. In fact, conformational changes induced by ephrin–EPH receptor interactions stabilize ADAM10–substrate complex formation and induce an enzymatic switch necessary for ephrin cleavage [62]. If HD dissociation occurs prior to S2 cleavage an inactive intermediate would exist (Fig. 3a; 2), which trimming by ADAM10 proteolysis would produce an effective γ-secretase substrate. Accordingly, a requirement for HD dissociation prior to S2 cleavage could provide an additional brake on ligand-induced Notch proteolytic activation and thereby represent a potential regulatory step.

4.3. The NRR structure provides a mechanism to regulate signal intensity

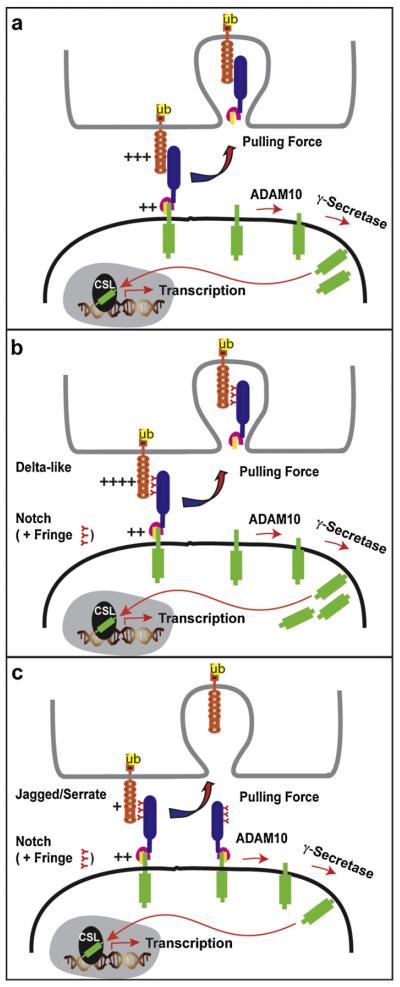

Regardless of the order of S2 cleavage with respect to HD dissociation, the force capable of rupturing ligand–receptor interactions must be greater than the force required to disengage the LNR and expose the S2 cleavage site and/or unfold the HD to dissociate the Notch heterodimer (Fig. 4a). Detection of transendocytosis of NECD by the ligand cell [30,48] indicates that ligand–receptor interactions are strong enough to survive the pulling force hypothesized for ligand endocytosis. The requirement for strong ligand–receptor interactions provides another potential regulatory step in the activation process. In this regard, modification of Notch by the family of Fringe N-acetylglucosamine transferases can alter the binding strength between Notch and its ligands [63]. While Fringe modification of Notch enhances the binding between Delta family proteins and Notch, it appears to decrease the affinity of Jagged/Serrate family proteins for the receptor. Moreover, Fringe proteins potentiate Delta activation of Notch while suppressing Notch activation by Jagged/Serrate, providing a mechanism to differentially modulate ligand signaling activity.

Fig. 4.

Fringe-mediated glycosylation differentially modulates ligand-induced Notch signaling levels. (a) To survive the ligand endocytic pull, ligand–receptor interactions (+++) must be stronger than the force required to unfold the NRR or dissociate the HD (++) for S2 exposure. (b) Fringe glycosylation of Notch enhances Delta–Notch interaction (++++) to increase the number of ligand–receptor pairs that survive the ligand endocytic pull, yielding more NICD for increased signaling. (c) Fringe glycosylation of Notch reduces Jagged/Serrate binding strength (+) to decrease survival of ligand–receptor interactions and consequently lower the level of active NICD for signaling.

Fringe activity is known to restrict Notch activation to specific domains as first described for the Dorsal/Ventral boundary during development and patterning of the Drosophila wing margin [64]. In mice, a role for Fringe modification to restrict Notch signaling among groups of cells during the process of sprouting angiogenesis has also been proposed [65]. Specifically, opposing signaling responses mediated by Dll4 and Jagged1 limit the number of sprouting tip cells and maintain stalk cell identity. By selectively activating or inhibiting Notch in a specific group of cells, Fringe modification can also contribute to lineage decisions in directing T-cell versus B-cell fates during lymphocyte development [66–68]. Although these studies suggest Fringe modification of Notch differentially regulates Notch ligand signaling activity, the underlying mechanism is still unclear.

Since Fringe modification alters ligand–receptor binding strength [69–71], it is attractive to speculate that the molecular basis of the observed Fringe-mediated effects result from differences in the level of NICD produced by the various ligand interactions with Fringe-modified Notch. Specifically, Delta–Notch interactions strengthened by Fringe modification would allow more ligand–receptor pairs to survive the pulling force generated by ligand endocytosis, thus yielding more NICD and increasing the level of signaling (Fig. 4a and b). In contrast, weakening of Jagged/Serrate–Notch interactions by Fringe modification would decrease the number of ligand–receptor pairs able to survive the pulling, resulting in less NICD generated and an overall decrease in signaling (Fig. 4a and c). In support of this notion, differences in Notch signaling level for different ligands in the presence of Fringe have been reported to induce distinct cellular responses following Notch activation [72,73]. By fine tuning ligand-induced Notch activity to mediate specific cellular outcomes, Fringe glycosylation may contribute to the well known pleiotropic affects ascribed to Notch signaling [1]. Whether ligand–receptor binding strength actually regulates NRR unfolding for S2 exposure and cleavage remains an exciting and testable model for the well-characterized Fringe modulation of Notch signaling by distinct ligands.

5. Conclusions

A series of highly choreographed conformational changes is proposed to override the NRR autoinhibited state. Whether the force-induced conformational changes activate signaling directly through S2 exposure alone or play additional roles in protease access and/or productive cleavage is currently unknown. Nonetheless, identification and characterization of the NRR structure, both the autoinhibited and active conformations, have facilitated design and development of highly specific and selective Notch therapeutics [74–76]. Notch signaling contributes to cancer through affects on both cell proliferation and angiogenesis required for tumor growth [3], identifying Notch as an attractive and logical drug target. Although γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) effectively block Notch signaling to revert malignant properties [57], intestinal toxicity due to general Notch inhibition induced by GSIs have limited their use [77]. Based on NRR structural findings, Notch paralog-specific NRR antibodies have been developed that successfully avoid the intestinal toxicity associated with pan-Notch inhibition [75]. These antibodies targeting the NRR bind simultaneously to the LNR and HD, functioning as molecular clamps to prevent Notch activation. Importantly, inhibitory NRR antibodies block ligand-induced Notch signaling and also prevent aberrant signaling associated with HD mutations in T-ALL.

Interestingly, NRR antibodies that activate signaling have also been reported [76], suggesting that antibody binding to the NRR exposes the S2 site for cleavage. Whether antibody-binding forces open the NRR structure or induces allosteric conformational changes similar to those produced by ligand remains to be determined. Although structural studies have provided insight into the mechanistic basis of ligand-induced Notch signaling, a combined biophysical approach will be necessary to demonstrate whether Notch ligand signaling activity is actually dependent on mechanical force intrinsic to ligand endocytosis. Furthermore, it will be important to determine whether ligand endocytic force induces NRR conformational changes that not only deprotect the S2 site but also regulate productive ADAM10-mediated Notch proteolysis. Finally, whether the NRR autoinhibited structure provides a mechanism to modulate signaling intensity and duration required to direct specific cellular responses is an exciting proposal for future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elliot Botvinick and Janice Fischer for helpful comments and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (A. M.), Jonsson Cancer Center Foundation (L. M-K.) and NIHGM (R01 GM085032) (G. W.) for support.

Abbreviations

- ADAM

a disintegrin and metalloprotease

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- CSL

CBF1

- Su(H)

LAG-1

- Dll

Delta-like

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GSI

γ-secretase inhibitor

- HD

heterodimerization domain

- LNRs

Lin12/Notch repeats

- NECD

Notch extracellular domain

- NICD

Notch intracellular domain

- NRR

negative regulatory region

- SOP

sensory organ precursor

- T-ALL

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

References

- [1].Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Muskavitch MA. Notch: the past, the present, and the future. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:1–29. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:678–89. doi: 10.1038/nrm2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Koch U, Radtke F. Notch and cancer: a double-edged sword. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2746–62. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7164-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].D’Souza B, Meloty-Kapella L, Weinmaster G. Canonical and non-canonical Notch ligands. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:73–129. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fortini ME, Bilder D. Endocytic regulation of Notch signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:323–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Furthauer M, Gonzalez-Gaitan M. Endocytic regulation of notch signalling during development. Traffic. 2009;10:792–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nichols JT, Miyamoto A, Weinmaster G. Notch signaling—constantly on the move. Traffic. 2007;8:959–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kovall RA, Blacklow SC. Mechanistic insights into Notch receptor signaling from structural and biochemical studies. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:31–71. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bozkulak EC, Weinmaster G. Selective use of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in activation of Notch1 signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5679–95. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00406-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brou C, Logeat F, Gupta N, Bessia C, LeBail O, Doedens JR, et al. A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the Disintegrin-Metalloprotease TACE. Mol Cell. 2000;5:207–16. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Delwig A, Rand MD. Kuz and TACE can activate Notch independent of ligand. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2232–43. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hartmann D, de Strooper B, Serneels L, Craessaerts K, Herreman A, Annaert W, et al. The disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM 10 is essential for Notch signalling but not for alpha-secretase activity in fibroblasts. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2615–24. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.21.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].van Tetering G, van Diest P, Verlaan I, van der Wall E, Kopan R, Vooijs M. Metalloprotease ADAM10 is required for Notch1 site 2 cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31018–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Struhl G, Adachi A. Requirements for presenilin-dependent cleavage of notch and other transmembrane proteins. Mol Cell. 2000;6:625–36. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bush G, diSibio G, Miyamoto A, Denault JB, Leduc R, Weinmaster G. Ligand-induced signaling in the absence of furin processing of Notch1. Dev Biol. 2001;229:494–502. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Logeat F, Bessia C, Brou C, LeBail O, Jarriault S, Seiday N, et al. The Notch1 receptor is cleaved constitutively by a furin-like convertase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8108–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Malecki MJ, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Mitchell JL, Histen G, Xu ML, Aster JC, et al. Leukemia-associated mutations within the NOTCH1 heterodimerization domain fall into at least two distinct mechanistic classes. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4642–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01655-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rand MD, Grimm LM, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Patriub V, Blacklow SC, Sklar J, et al. Calcium depletion dissociates and activates heterodimeric notch receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1825–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1825-1835.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sanchez-Irizarry C, Carpenter AC, Weng AP, Pear WS, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Notch subunit heterodimerization and prevention of ligand-independent proteolytic activation depend, respectively, on a novel domain and the LNR repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9265–73. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9265-9273.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kidd S, Lieber T. Furin cleavage is not a requirement for Drosophila Notch function. Mech Dev. 2002;115:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Blaumueller CM, Qi H, Zagouras P, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Intracellular cleavage of Notch leads to a heterodimeric receptor on the plasma membrane. Cell. 1997;90:281–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pan D, Rubin GM. Kuzbanian controls proteolytic processing of Notch and mediates lateral inhibition during Drosophila and vertebrate neurogenesis. Cell. 1997;90:271–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Vaccari T, Lu H, Kanwar R, Fortini ME, Bilder D. Endosomal entry regulates Notch receptor activation in Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:755–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lake RJ, Grimm LM, Veraksa A, Banos A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. In vivo analysis of the Notch receptor S1 cleavage. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gordon WR, Vardar-Ulu D, L’Heureux S, Ashworth T, Malecki MJ, Sanchez-Irizarry C, et al. Effects of S1 cleavage on the structure, surface export, and signaling activity of human Notch1 and Notch2. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Poodry CA. shibire, a neurogenic mutant of Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1990;138:464–72. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:857–902. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081307.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Seugnet L, Simpson P, Haenlin M. Requirement for dynamin during Notch signaling in Drosophila neurogenesis. Dev Biol. 1997;192:585–98. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Parks AL, Klueg KM, Stout JR, Muskavitch MA. Ligand endocytosis drives receptor dissociation and activation in the Notch pathway. Development. 2000;127:1373–85. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.7.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Deblandre GA, Lai EC, Kintner C. Xenopus neuralized is a ubiquitin ligase that interacts with XDelta1 and regulates Notch signaling. Dev Cell. 2001;1:795–806. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Itoh M, Kim CH, Palardy G, Oda T, Jiang YJ, Maust D, et al. Mind bomb is a ubiquitin ligase that is essential for efficient activation of Notch signaling by Delta. Dev Cell. 2003;4:67–82. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lai EC, Deblandre GA, Kintner C, Rubin GM. Drosophila neuralized is a ubiquitin ligase that promotes the internalization and degradation of delta. Dev Cell. 2001;1:783–94. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pavlopoulos E, Pitsouli C, Klueg KM, Muskavitch MA, Moschonas NK. Delidakis C. neuralized encodes a peripheral membrane protein involved in delta signaling and endocytosis. Dev Cell. 2001;1:807–16. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Overstreet E, Fitch E, Fischer JA. Fat facets and liquid facets promote Delta endocytosis and Delta signaling in the signaling cells. Development. 2004;131:5355–66. doi: 10.1242/dev.01434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wang W, Struhl G. Drosophila Epsin mediates a select endocytic pathway that DSL ligands must enter to activate Notch. Development. 2004;131:5367–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.01413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wang W, Struhl G. Distinct roles for Mind bomb, Neuralized and Epsin in mediating DSL endocytosis and signaling in Drosophila. Development. 2005;132:2883–94. doi: 10.1242/dev.01860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Maldonado-Baez L, Wendland B. Endocytic adaptors: recruiters, coordinators and regulators. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:505–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Weinmaster G, Fischer JA. Notch ligand ubiquitylation: what is it good for. Dev Cell. 2011;21:134–44. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yamamoto S, Charng WL, Bellen HJ. Endocytosis and intracellular trafficking of Notch and its ligands. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:165–200. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92005-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Heuss SF, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Six EM, Israel A, Logeat F. The intracellular region of Notch ligands Dll1 and Dll3 regulates their trafficking and signaling activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11212–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800695105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Benhra N, Vignaux F, Dussert A, Schweisguth F, Le Borgne R. Neuralized promotes basal to apical transcytosis of delta in epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2078–86. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-11-0926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Emery G, Hutterer A, Berdnik D, Mayer B, Wirtz-Peitz F, Gaitan MG, et al. Asymmetric Rab 11 endosomes regulate delta recycling and specify cell fate in the Drosophila nervous system. Cell. 2005;122:763–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Jafar-Nejad H, Andrews HK, Acar M, Bayat V, Wirtz-Peitz F, Mehta SQ, et al. Sec15, a component of the exocyst, promotes notch signaling during the asymmetric division of Drosophila sensory organ precursors. Dev Cell. 2005;9:351–63. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rajan A, Tien AC, Haueter CM, Schulze KL, Bellen HJ. The Arp2/3 complex and WASp are required for apical trafficking of Delta into microvilli during cell fate specification of sensory organ precursors. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:815–24. doi: 10.1038/ncb1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Banks SM, Cho B, Eun SH, Lee JH, Windler SL, Xie X, et al. The functions of auxilin and Rab11 in Drosophila suggest that the fundamental role of ligand endocytosis in notch signaling cells is not recycling. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Windler SL, Bilder D. Endocytic internalization routes required for Delta/Notch signaling. Curr Biol. 2010;20:538–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nichols JT, Miyamoto A, Olsen SL, D’Souza B, Yao C, Weinmaster G. DSL ligand endocytosis physically dissociates Notch1 heterodimers before activating proteolysis can occur. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:445–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Liu J, Sun Y, Drubin DG, Oster GF. The mechanochemistry of endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Gordon WR, Arnett KL, Blacklow SC. The molecular logic of Notch signaling—a structural and biochemical perspective. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3109–19. doi: 10.1242/jcs.035683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gordon WR, Roy M, Vardar-Ulu D, Garfinkel M, Mansour MR, Aster JC, et al. Structure of the Notch1-negative regulatory region: implications for normal activation and pathogenic signaling in T-ALL. Blood. 2009;113:4381–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Gordon WR, Vardar-Ulu D, Histen G, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Structural basis for autoinhibition of Notch. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tiyanont K, Wales TE, Aste-Amezaga M, Aster JC, Engen JR, Blacklow SC. Evidence for increased exposure of the Notch1 metalloprotease cleavage site upon conversion to an activated conformation. Structure. 2011;19:546–54. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kopan R, Schroeter EH, Weintraub H, Nye JS. Signal transduction by activated mNotch: importance of proteolytic processing and its regulation by the extracellular domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1683–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lieber T, Kidd S, Alcamo E, Corbin V, Young MW. Antineurogenic phenotypes induced by truncated Notch proteins indicate a role in signal transduction and may point to a novel function for Notch in nuclei. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1949–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rebay I, Fehon RG, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Specific truncations of Drosophila Notch define dominant activated and dominant negative forms of the receptor. Cell. 1993;74:319–29. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90423-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Pt Morris J, Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ahimou F, Mok LP, Bardot B, Wesley C. The adhesion force of Notch with Delta and the rate of Notch signaling. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1217–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Chen J, Zolkiewska A. Force-induced unfolding simulations of the human Notch1 negative regulatory region: possible roles of the heterodimerization domain in mechanosensing. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lieber T, Kidd S, Young MW. kuzbanian-mediated cleavage of Drosophila Notch. Genes Dev. 2002;16:209–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.942302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Reddy P, Stocking KL, Sunnarborg SW, Lee DC, et al. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science. 1998;282:1281–4. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Janes PW, Saha N, Barton WA, Kolev MV, Wimmer-Kleikamp SH, Nievergall E, et al. Adam meets Eph: an ADAM substrate recognition module acts as a molecular switch for ephrin cleavage in trans. Cell. 2005;123:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Stanley P, Okajima T. Roles of glycosylation in Notch signaling. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:131–64. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Rauskolb C, Correia T, Irvine KD. Fringe-dependent separation of dorsal and ventral cells in the Drosophila wing. Nature. 1999;401:476–80. doi: 10.1038/46786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Benedito R, Roca C, Sorensen I, Adams S, Gossler A, Fruttiger M, et al. The notch ligands Dll4 and Jagged1 have opposing effects on angiogenesis. Cell. 2009;137:1124–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Koch U, Lacombe TA, Holland D, Bowman JL, Cohen BL, Egan SE, et al. Subversion of the T/B lineage decision in the thymus by lunatic fringe-mediated inhibition of Notch-1. Immunity. 2001;15:225–36. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Visan I, Tan JB, Yuan JS, Harper JA, Koch U, Guidos CJ. Regulation of T lymphopoiesis by Notch1 and Lunatic fringe-mediated competition for intrathymic niches. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:634–43. doi: 10.1038/ni1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Visan I, Yuan JS, Tan JB, Cretegny K, Guidos CJ. Regulation of intrathymic T-cell development by Lunatic Fringe–Notch1 interactions. Immunol Rev. 2006;209:76–94. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Okajima T, Xu A, Irvine KD. Modulation of notch-ligand binding by protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 and fringe. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42340–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Panin VM, Papayannopoulos V, Wilson R, Irvine KD. Fringe modulates Notch–ligand interactions. Nature. 1997;387:908–12. doi: 10.1038/43191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Xu A, Haines N, Dlugosz M, Rana NA, Takeuchi H, Haltiwanger RS, et al. In vitro reconstitution of the modulation of Drosophila Notch–ligand binding by Fringe. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35153–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Abe N, Hozumi K, Hirano K, Yagita H, Habu S. Notch ligands transduce different magnitudes of signaling critical for determination of T-cell fate. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2608–17. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Van de Walle I, De Smet G, Gartner M, De Smedt M, Waegemans E, Vandekerckhove B, et al. Jagged2 acts as a Delta-like Notch ligand during early hematopoietic cell fate decisions. Blood. 2011;117:4449–59. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Aste-Amezaga M, Zhang N, Lineberger JE, Arnold BA, Toner TJ, Gu M, et al. Characterization of Notch1 antibodies that inhibit signaling of both normal and mutated Notch1 receptors. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wu Y, Cain-Hom C, Choy L, Hagenbeek TJ, de Leon GP, Chen Y, et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting of individual Notch receptors. Nature. 2010;464:1052–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Li K, Li Y, Wu W, Gordon WR, Chang DW, Lu M, et al. Modulation of Notch signaling by antibodies specific for the extracellular negative regulatory region of NOTCH3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8046–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800170200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].van Es JH, van Gijn ME, Riccio O, van den Born M, Vooijs M, Begthel H, et al. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435:959–63. doi: 10.1038/nature03659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]