Abstract

Growth-promoting and nutrient/mitogen-sensing pathways such as mTOR convert p21- and p16-induced arrest into senescence (geroconversion). We have recently demonstrated that hypoxia, especially near-anoxia, suppresses geroconversion. This gerosuppressive effect of hypoxia correlated with inhibition of the mTOR/S6K pathway but not with modulation of the LKB1/AMPK/eEF2 pathway. Here we further show that mTOR inhibition is required for gerosuppression by hypoxia, at least in some cellular models, because depletion of TSC2 abolished mTOR inhibition and gerosupression by hypoxia. Also, in two cancer cell lines resistant to inhibition of mTOR by both p53 and hypoxia, hypoxia did not suppress geroconversion. Therefore, the effects of hypoxia on the oxygen-sensing mTOR pathway and geroconversion are cell type-specific. We also briefly discuss replicative senescence, organismal aging and free radical theory.

Keywords: aging, senescence, mTOR, cancer

Hypoxia can cause cell cycle arrest. However, reversible cell cycle arrest is not yet irreversible senescence.1 Indeed, hypoxia did not cause senescence in several cell lines tested by us, and we did not find well-documented reports of hypoxia-induced senescence. This may seem puzzling given that hypoxia activates hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) and HIF-dependent secretion of VEGF, PAI, IGF-I and other cytokines. And hyper-secretory phenotype or senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) is one of the hallmarks of cellular senescence.2-5

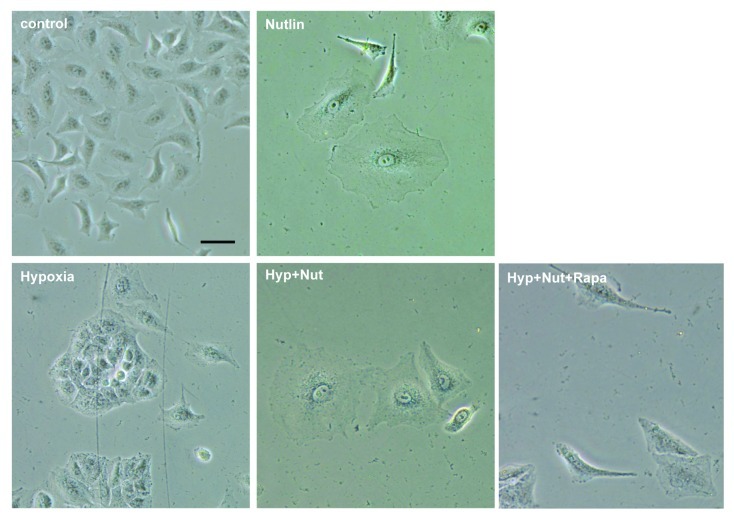

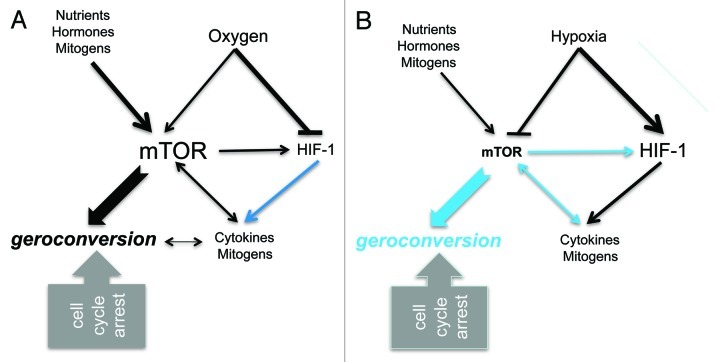

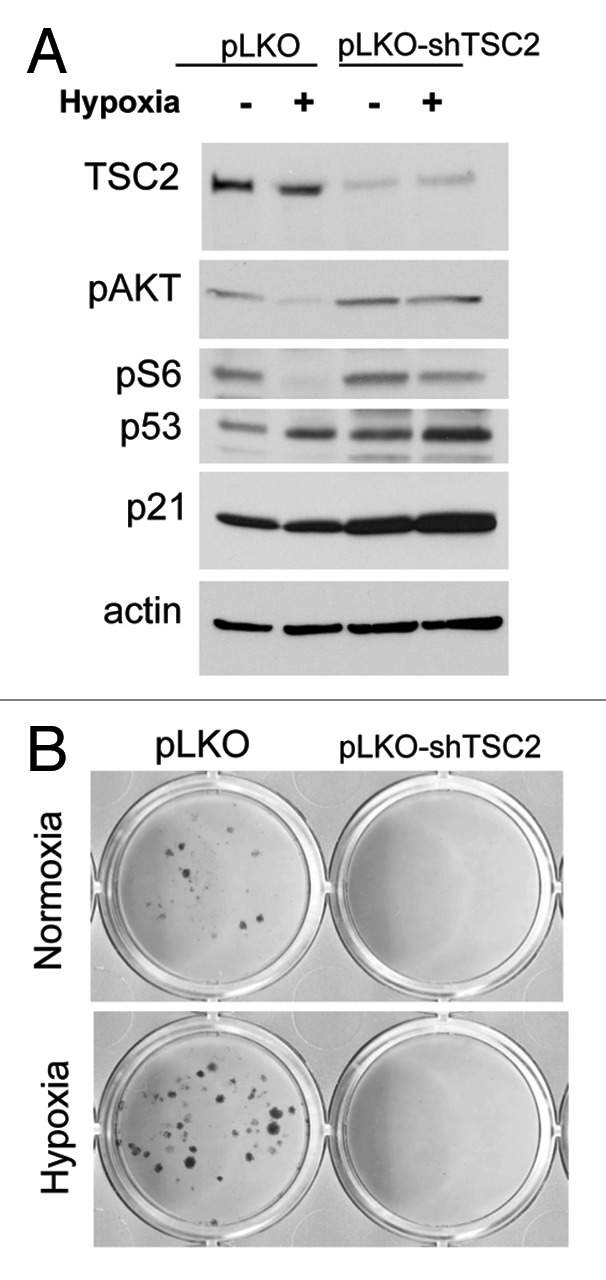

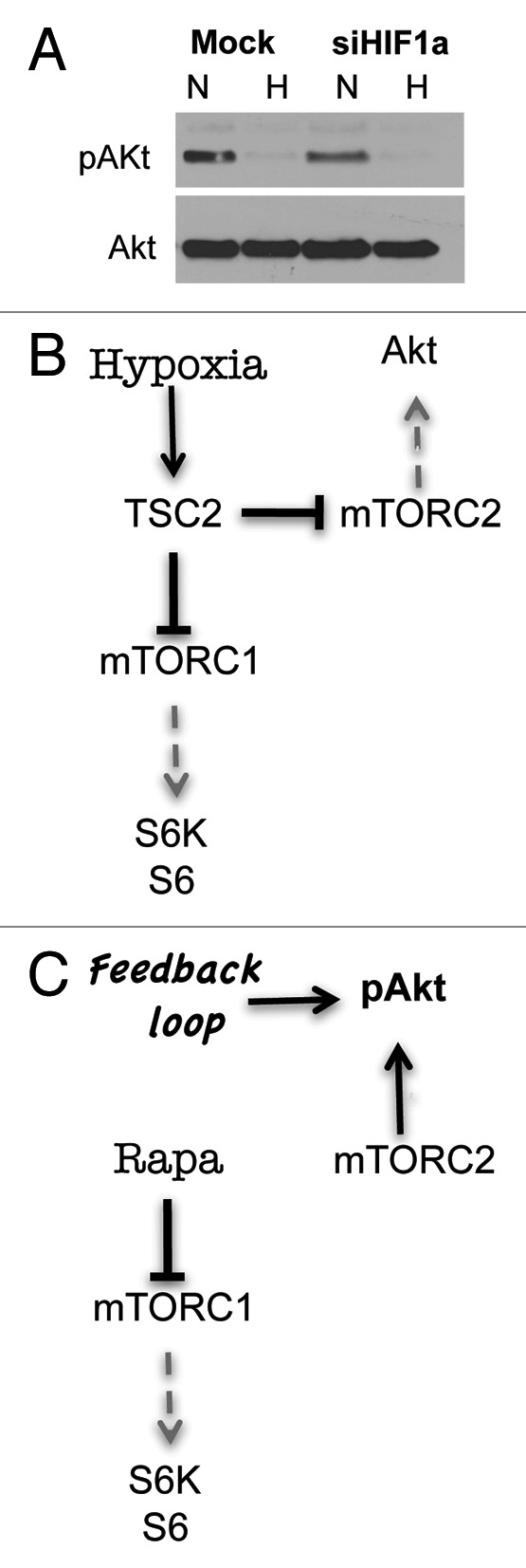

Possibly, while inducing some manifestations of senescence such as secretory phenotype, hypoxia suppresses the underlying senescence-driving (gerogenic) process. Thus, a senescent program (conversion from cell cycle arrest to senescence or geroconversion) depends in part on the nutrient-sensing and growth-promoting mTOR (target of rapamycin) pathway. Activation of the mTOR pathway is involved in secretion of numerous cytokines as a part of hypersecretory phenotype of senescent cells.6-8 Importantly, the mTOR pathway is responsible for a large-cell morphology and irreversible loss of regenerative (replicative) potential. Rapamycin suppresses geroconversion during cell cycle arrest.9-17 Hypoxia inhibits mTOR.18-27 This may not only explain why hypoxia does not cause senescence, but also why it suppresses geroconversion caused by senescence-inducing agents. For example, induction of ectopic p21 by IPTG causes cell cycle arrest without inhibiting mTOR, thus leading to senescence in HT-p21 cells.28 These cells acquired a large-flat morphology and lost regenerative (replicative) potential, becoming unable to resume proliferation after p21 is switched off. If p21 was induced under hypoxia, cells were arrested but did not become large and retained regenerative (replicative) potential, forming colonies upon IPTG removal.28 Using several inducers of senescence, we demonstrated this phenomenon in a variety of cell lines. In all cases, suppression of geroconversion coincided with the inhibition of mTOR by hypoxia. It was independent from p53, HIF-1 and AMPK. Although hypoxia exerted multiple other effects, it seems that inhibition of mTOR was sufficient to suppress senescence, because rapamycin was even more effective than hypoxia as a gerosuppressor (in the same cell lines) and did not have additive effects with hypoxia.28 Here we further showed that, at least in HT-p21 cells, the inhibition of mTOR was required for gerosuppression. We infected these cells with lentivirus expressing shRNA for TSC2 (shTSC2), which decreased levels of TSC2, a negative regulator of mTOR (Fig. 1A). TSC2 knockout prevented inhibition of mTOR by hypoxia, as evidenced by persistent phosphorylation of S6K and S6 (downstream targets of mTOR complex 1) and Akt (a downstream target of mTORC2) under hypoxia (Fig. 1A). Notably, both inhibition of pS6 phosphorylation28 and Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 2A) were HIF-1 independent. In contrast, rapamycin increased Akt phosphorylation in the same cell line10 (Fig. 2B and C). Hypoxia partially prevented loss of replicative/regenerative potential (RP), meaning that some cells could resume proliferation after IPTG was washed out (Fig. 1B). In contrast, hypoxia failed to prevent loss of RP in HT-p21 cells with depleted TSC2, indicating that inhibition of mTOR is required for gerosuppression by hypoxia at least in these cells.

Figure 1. TSC2 is required for gerosuppression in HT-p21–9 cells. HT-p21–9 cells, infected with lentivirus vector pLKO or pLKO-shTSC2 (see ref. 31), were treated with IPTG in normoxia or 0.2% O2 hypoxia. (A) After 24 h, cells were lysed, and immunoblotting was performed with the indicated antibodies as described previously.28 (B) After 4 d, cells were washed and allowed to regrow. Colonies were stained with Crystal Violet as described previously.28

Figure 2. Hypoxia inhibits AKT phosphorylation in HIF-1-independent manner in HT-p21–9 cells. (A) HT-p21–9 cells, mock-transfected or transfected with siRNA for HIF-1α, were incubated under normoxia or hypoxia (0.2% O2) as described in (see ref. 28). After 3 d, cells were lysed and immunoblotting was performed as described.28 using anti-pAkt (Ser 473) antibodies. The other proteins are shown in the PNAS paper (Fig. 2B in ref. 28). (B) Hypothetical schema of the effects of hypoxia on pS6 and pAkt in HT-p21–9 cells. In TSC2-dependent and HIF-1-independent manner, hypoxia inhibits mTORC1 and mTORC2 and thus inhibits phosphorylation of S6 and Akt. (C) Hypothetical schema of the effects of rapamycin on pS6 and pAkt in HT-p21–9 cells. Rapamycin inhibits mTORC1 and stimulates Akt phosphorylation via a feedback loop.

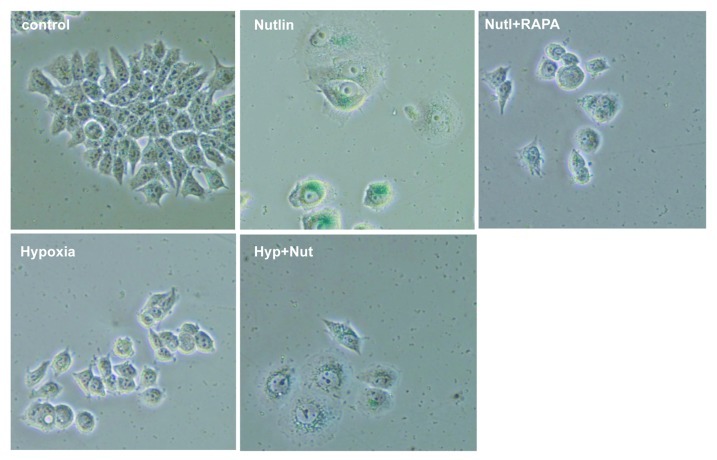

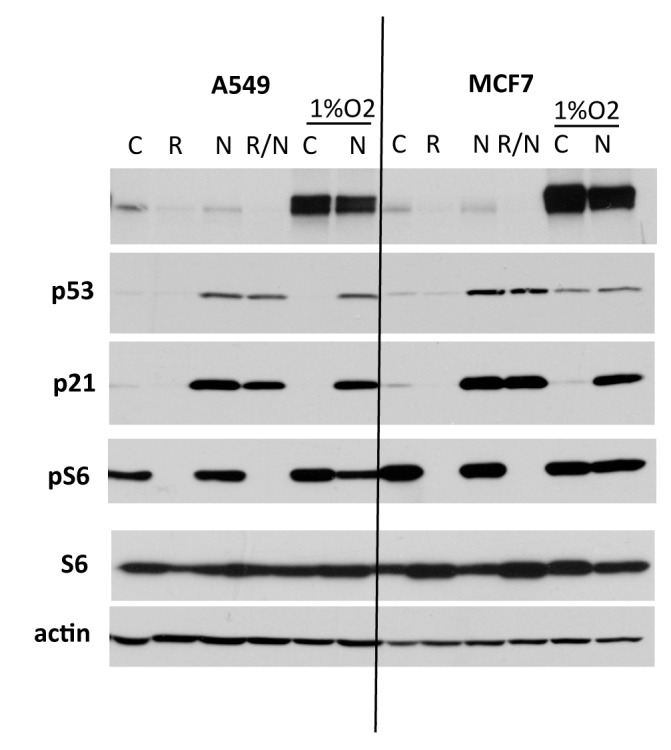

Furthermore, we have previously identified cell lines in which hypoxia did not inhibit mTOR and geroconversion.28 This is reminiscent of the effect of non-genotoxic induction of p53 by nutlin-3a. Nutlin-3a inhibited mTOR and suppressed geroconversion during p21-induced arrest in HT-p21 cells and in normal cells.29,30 Yet, it did not inhibit mTOR in some cancer cell lines and MEFs.31,30 Next, we chose cell lines (A549 and MCF-7) in which low concentrations of nutlin-3 did not inhibit mTOR (Fig. 3). These cells become senescent following treatment with nutlin-3a (Figs. 4 and 5). Unlike rapamycin, hypoxia did not inhibit mTOR in A549 and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3). In agreement, hypoxia did not suppress morphological senescence caused by nutlin-3a, whereas rapamycin did (Figs. 4 and 5). Thus, inhibition of mTOR by hypoxia seems to be a prerequisite of gerosuppression by hypoxia.

Figure 3. The effect of hypoxia and nutlin-3a on MCF-7 and A549. A549 and MCF7 cancer cells were treated with 5 uM of nutlin-3a with or without 10 nM (A549) or 100 nM (MCF7) rapamycin under normoxia or 1% O2 hypoxia. After 24 h, cells were lysed, and immunoblotting was performed with the indicated antibodies (see ref. 28).

Figure 4. The effect of hypoxia and rapamycin on nutlin-3a-induced senescence in A549 cells. A549 cells were treated with 5 uM nutlin-3a (Nut) and 10 nM rapamycin (Rapa) under normoxia or 1% O2 hypoxia (Hyp) for 4 d and stained for β-Gal. Bar = 100 um.

Figure 5. The effect of hypoxia and rapamycin on nutlin-3a-induced senescence in MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells were treated with 5 uM nutlin-3a (Nut) and 100 nM rapamycin (Rapa) under normoxia or 1% O2 hypoxia (Hyp) for 4 d and stained for β-Gal. Bar = 100 um.

Our studies can explain abrogation of replicative senescence by hypoxia in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) observed by Campisi and coworkers.32 In fact, hypoxia inhibits mTOR in MEF cells.20 Rapamycin can also suppress senescence in MEFs; however, its effect is limited by its cytostatic effect.33 We can speculate that mild hypoxia slightly inhibited mTOR without inhibiting cell proliferation, thus creating a condition for avoidance of mTOR-dependent senescence. Since hypoxia is a normal physiological condition inside an organism, this may explain why geroconversion of normal cells may take decades in humans.

Our study has one startling implication. Thousands of experiments with oxygen and hypoxia were interpreted as the evidence for the free radical theory of aging. Yet, these data can have alternative explanations. Instead of accumulation of random damage caused by free radicals, oxygen can activate oxygen-sensing pathways such as TOR (Fig. 6). Interestingly, NAC (the most commonly used agent to decrease free radicals) turned out to inhibit the mTOR pathway in some cells too.34 In our experiments, the gerosuppressive effect of hypoxia depended on whether it inhibited the mTOR pathway. Slight genetic alterations, differences between cell lines and levels of oxygen may determine the effect of oxygen on geroconversion. This is difficult to reconcile with the free radical theory. Also free radical theory of aging does not fit observations in model organisms.35-48 In agreement, inhibition of TOR prolongs lifespan in model organisms,49-61 supporting the notion that mTOR-driven cellular hyper-functions (cellular aging) lead to age-related diseases and organismal death.62-65

Figure 6. The relationships between hypoxia, HIF-1, mTOR and geroconversion. (A) Under normoxia, when the cell cycle is arrested, still active mTOR drives cellular senescence. mTOR is activated by nutrients, mitogens, cytokines and oxygen. As a part of geroconversion, mTOR stimulates cytokine secretion. Black lines: stimulatory and inhibitory effects. Blue lines: inactive under normoxia. (B) Under severe hypoxia, the mTOR pathway and geroconversion are partially inhibited. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is accumulated. HIF-1-dependent cytokine secretion may activate the mTOR pathway in neighboring oxygenated cells. Blue lines, inactive under hypoxia.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Brugarolas and Mikhail A. Nikiforov for critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21908

References

- 1.Blagosklonny MV. Cell cycle arrest is not yet senescence, which is not just cell cycle arrest: terminology for TOR-driven aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:159–65. doi: 10.18632/aging.100443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Muñoz DP, Goldstein J, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2853–68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coppé JP, Kauser K, Campisi J, Beauséjour CM. Secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor by primary human fibroblasts at senescence. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29568–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodier F, Coppé JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Muñoz DP, Raza SR, et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:973–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodier F, Muñoz DP, Teachenor R, Chu V, Le O, Bhaumik D, et al. DNA-SCARS: distinct nuclear structures that sustain damage-induced senescence growth arrest and inflammatory cytokine secretion. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:68–81. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narita M, Young AR, Arakawa S, Samarajiwa SA, Nakashima T, Yoshida S, et al. Spatial coupling of mTOR and autophagy augments secretory phenotypes. Science. 2011;332:966–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1205407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pani G. From growing to secreting: new roles for mTOR in aging cells. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2450–3. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.15.16886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capparelli C, Guido C, Whitaker-Menezes D, Bonuccelli G, Balliet R, Pestell TG, et al. Autophagy and senescence in cancer-associated fibroblasts metabolically supports tumor growth and metastasis via glycolysis and ketone production. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2285–302. doi: 10.4161/cc.20718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. Growth stimulation leads to cellular senescence when the cell cycle is blocked. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3355–61. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.21.6919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demidenko ZN, Zubova SG, Bukreeva EI, Pospelov VA, Pospelova TV, Blagosklonny MV. Rapamycin decelerates cellular senescence. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1888–95. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demidenko ZN, Shtutman M, Blagosklonny MV. Pharmacologic inhibition of MEK and PI-3K converges on the mTOR/S6 pathway to decelerate cellular senescence. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1896–900. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. Quantifying pharmacologic suppression of cellular senescence: prevention of cellular hypertrophy versus preservation of proliferative potential. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:1008–16. doi: 10.18632/aging.100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pospelova TV, Demidenko ZN, Bukreeva EI, Pospelov VA, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. Pseudo-DNA damage response in senescent cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:4112–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.24.10215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leontieva OV, Blagosklonny MV. DNA damaging agents and p53 do not cause senescence in quiescent cells, while consecutive re-activation of mTOR is associated with conversion to senescence. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:924–35. doi: 10.18632/aging.100265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leontieva OV, Demidenko ZN, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. Elimination of proliferating cells unmasks the shift from senescence to quiescence caused by rapamycin. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romanov VS, Abramova MV, Svetlikova SB, Bykova TV, Zubova SG, Aksenov ND, et al. p21(Waf1) is required for cellular senescence but not for cell cycle arrest induced by the HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3945–55. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.19.13160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolesnichenko M, Hong L, Liao R, Vogt PK, Sun P. Attenuation of TORC1 signaling delays replicative and oncogenic RAS-induced senescence. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2391–401. doi: 10.4161/cc.20683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sofer A, Lei K, Johannessen CM, Ellisen LW. Regulation of mTOR and cell growth in response to energy stress by REDD1. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5834–45. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.5834-5845.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arsham AM, Howell JJ, Simon MC. A novel hypoxia-inducible factor-independent hypoxic response regulating mammalian target of rapamycin and its targets. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29655–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, Manning BD, Reiling JH, Hafen E, et al. Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2893–904. doi: 10.1101/gad.1256804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connolly E, Braunstein S, Formenti S, Schneider RJ. Hypoxia inhibits protein synthesis through a 4E-BP1 and elongation factor 2 kinase pathway controlled by mTOR and uncoupled in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3955–65. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3955-3965.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young RM, Wang SJ, Gordan JD, Ji X, Liebhaber SA, Simon MC. Hypoxia-mediated selective mRNA translation by an internal ribosome entry site-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16309–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710079200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeYoung MP, Horak P, Sofer A, Sgroi D, Ellisen LW. Hypoxia regulates TSC1/2-mTOR signaling and tumor suppression through REDD1-mediated 14-3-3 shuttling. Genes Dev. 2008;22:239–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.1617608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider A, Younis RH, Gutkind JS. Hypoxia-induced energy stress inhibits the mTOR pathway by activating an AMPK/REDD1 signaling axis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1295–302. doi: 10.1593/neo.08586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cam H, Easton JB, High A, Houghton PJ. mTORC1 signaling under hypoxic conditions is controlled by ATM-dependent phosphorylation of HIF-1α. Mol Cell. 2010;40:509–20. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knaup KX, Jozefowski K, Schmidt R, Bernhardt WM, Weidemann A, Juergensen JS, et al. Mutual regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor and mammalian target of rapamycin as a function of oxygen availability. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:88–98. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolff NC, Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S, Xie XJ, Castrillon DH, Kabbani W, Brugarolas J. Cell-type-dependent regulation of mTORC1 by REDD1 and the tumor suppressors TSC1/TSC2 and LKB1 in response to hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1870–84. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01393-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leontieva OV, Natarajan V, Demidenko ZN, Burdelya LG, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. Hypoxia suppresses conversion from proliferative arrest to cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:13314–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205690109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demidenko ZN, Korotchkina LG, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. Paradoxical suppression of cellular senescence by p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9660–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002298107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leontieva OV, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. Weak p53 permits senescence during cell cycle arrest. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4323–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korotchkina LG, Leontieva OV, Bukreeva EI, Demidenko ZN, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. The choice between p53-induced senescence and quiescence is determined in part by the mTOR pathway. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:344–52. doi: 10.18632/aging.100160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parrinello S, Samper E, Krtolica A, Goldstein J, Melov S, Campisi J. Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:741–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pospelova TV, Leontieva OV, Bykova TV, Zubova SG, Pospelov VA, Blagosklonny MV. Suppression of replicative senescence by rapamycin in rodent embryonic cells. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2402–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.20882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leontieva OV, Blagosklonny MV. Yeast-like chronological senescence in mammalian cells: phenomenon, mechanism and pharmacological suppression. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:1078–91. doi: 10.18632/aging.100402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doonan R, McElwee JJ, Matthijssens F, Walker GA, Houthoofd K, Back P, et al. Against the oxidative damage theory of aging: superoxide dismutases protect against oxidative stress but have little or no effect on life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3236–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.504808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gems D, Doonan R. Antioxidant defense and aging in C. elegans: is the oxidative damage theory of aging wrong? Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1681–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cabreiro F, Ackerman D, Doonan R, Araiz C, Back P, Papp D, et al. Increased life span from overexpression of superoxide dismutase in Caenorhabditis elegans is not caused by decreased oxidative damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1575–82. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lapointe J, Hekimi S. When a theory of aging ages badly. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Raamsdonk JM, Meng Y, Camp D, Yang W, Jia X, Bénard C, et al. Decreased energy metabolism extends life span in Caenorhabditis elegans without reducing oxidative damage. Genetics. 2010;185:559–71. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.115378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Speakman JR, Selman C. The free-radical damage theory: Accumulating evidence against a simple link of oxidative stress to ageing and lifespan. Bioessays. 2011;33:255–9. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ristow M, Schmeisser S. Extending life span by increasing oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gems DH, de la Guardia YI. Alternative Perspectives on Aging in C. elegans: Reactive Oxygen Species or Hyperfunction? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012 doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4840. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pani G. P66SHC and ageing: ROS and TOR? Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:514–8. doi: 10.18632/aging.100182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanz A, Fernández-Ayala DJ, Stefanatos RK, Jacobs HT. Mitochondrial ROS production correlates with, but does not directly regulate lifespan in Drosophila. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:200–23. doi: 10.18632/aging.100137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blagosklonny MV. Paradoxes of aging. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2997–3003. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.24.5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blagosklonny MV. Aging: ROS or TOR. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3344–54. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.21.6965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blagosklonny MV. Why the disposable soma theory cannot explain why women live longer and why we age. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:884–7. doi: 10.18632/aging.100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blagosklonny MV. Molecular damage in cancer: an argument for mTOR-driven aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:1130–41. doi: 10.18632/aging.100422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stipp D. A new path to longevity. Sci Am. 2012;306:32–9. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0112-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaeberlein M, Kennedy BK. Ageing: A midlife longevity drug? Nature. 2009;460:331–2. doi: 10.1038/460331a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blagosklonny MV. Rapamycin and quasi-programmed aging: four years later. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1859–62. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.10.11872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaeberlein M, Powers RW, 3rd, Steffen KK, Westman EA, Hu D, Dang N, et al. Regulation of yeast replicative life span by TOR and Sch9 in response to nutrients. Science. 2005;310:1193–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1115535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kapahi P, Zid BM, Harper T, Koslover D, Sapin V, Benzer S. Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2004;14:885–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Selman C, Tullet JM, Wieser D, Irvine E, Lingard SJ, Choudhury AI, et al. Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 signaling regulates mammalian life span. Science. 2009;326:140–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1177221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moskalev AA, Shaposhnikov MV. Pharmacological inhibition of phosphoinositide 3 and TOR kinases improves survival of Drosophila melanogaster. Rejuvenation Res. 2010;13:246–7. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bjedov I, Toivonen JM, Kerr F, Slack C, Jacobson J, Foley A, et al. Mechanisms of life span extension by rapamycin in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 2010;11:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller RA, Harrison DE, Astle CM, Baur JA, Boyd AR, de Cabo R, et al. Rapamycin, but not resveratrol or simvastatin, extends life span of genetically heterogeneous mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:191–201. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anisimov VN, Zabezhinski MA, Popovich IG, Piskunova TS, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML, et al. Rapamycin increases lifespan and inhibits spontaneous tumorigenesis in inbred female mice. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:4230–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.24.18486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang M, Miller RA. Augmented autophagy pathways and MTOR modulation in fibroblasts from long-lived mutant mice. Autophagy. 2012;8:8. doi: 10.4161/auto.20917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilkinson JE, Burmeister L, Brooks SV, Chan CC, Friedline S, Harrison DE, et al. Rapamycin slows aging in mice. Aging Cell. 2012;11:675–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blagosklonny MV. Aging and immortality: quasi-programmed senescence and its pharmacologic inhibition. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2087–102. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.18.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blagosklonny MV. TOR-driven aging: speeding car without brakes. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:4055–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.24.10310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blagosklonny MV. Revisiting the antagonistic pleiotropy theory of aging: TOR-driven program and quasi-program. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3151–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.13120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blagosklonny MV. Prospective treatment of age-related diseases by slowing down aging. Am J Pathol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.024. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]