Abstract

Development of RNA interference (RNAi)-based therapeutics has been hampered by the lack of effective and efficient means of delivery. Reliable model systems for screening and optimizing delivery of RNAi-based agents in vivo are crucial for preclinical research aimed at advancing nucleic acid-based therapies. We describe here a dual fluorescent reporter xenograft melanoma model prepared by intradermal injection of human A375 melanoma cells expressing tandem tomato fluorescent protein (tdTFP) containing a small interfering RNA (siRNA) target site as well as enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), which is used as a normalization control. Intratumoral injection of a siRNA specific to the incorporated siRNA target site, complexed with a cationic lipid that has been optimized for in vivo delivery, resulted in 65%±11% knockdown of tdTFP relative to EGFP quantified by in vivo imaging and 68%±10% by reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction. No effect was observed with nonspecific control siRNA treatment. This model provides a platform on which siRNA delivery technologies can be screened and optimized in vivo.

Introduction

The discovery that small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) can potently and selectively inhibit target gene expression has opened up novel treatment opportunities and has revolutionized the study of gene function. A number of clinical trials using RNA interference (RNAi)-based therapeutics (Burnett and Rossi, 2012) including those of the skin (Leachman et al., 2010) are underway or have been completed with encouraging results. Disorders of the skin, including skin cancers, will be good candidates for RNAi-based therapies if delivery hurdles are overcome (Kaspar, et al., 2009).

Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer among males (sixth for females), and its incidence is rising faster than other common cancers (www.skincancer.org/Skin-Cancer-Facts/#melanoma). Existing treatments include direct excision (Mohs surgery; Kwon and Miller, 2011) or immunotherapy (Guida et al., 2012; Monzon and Dancey, 2012), as well as chemotherapy (Finn et al., 2012). Each of these approaches has drawbacks and coulzd potentially benefit from combination with RNAi-based therapeutics (Kudchadkar et al., 2012). siRNAs are potent and highly specific, with the ability to distinguish single nucleotide differences (Jackson and Linsley, 2010), providing the ability to target specific oncogenes.

Translation of siRNA therapeutics to the clinic for treatment of skin disorders, including melanoma, requires more efficient delivery systems, which are the focus of this study. Current siRNA delivery systems including intradermal injection (Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al., 2009), microneedle administration (Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al., 2010), and topical administration (Hsu and Mitragotri, 2011) provide only partial inhibition of targeted genes, which may not be sufficient to achieve a therapeutic effect. Existing methods for evaluation of functional siRNA delivery [e.g., reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)] are time consuming and inefficient (i.e., mice need to be sacrificed for each time point), making them unattractive for screening. The ability to intravitally image live animals for functional siRNA delivery in real time would facilitate rapid screening of delivery strategies without the need to process tissue samples postmortem, allowing repeated imaging of the same mice, greatly reducing issues of mouse-to-mouse variability and decreasing the number of mice required.

Materials and Methods

Design of siRNA

Ambion® In Vivo siRNAs were utilized in this study (Life Technologies, Austin, TX). The click beetle luciferase-3 (CBL3) siRNA sense and antisense sequences are 5′-TTT ACG TCG TGG ATC GTT AdTdT and 5′-UAA CGA UCC ACG ACG UAA AdTdT respectively (Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al. 2009). The nonspecific control siRNA, Neg1 (Life Technologies), sense and antisense sequences are: 5′-AGU ACU GCU UAC GAU ACG GdTdT and 5′-CCG UAU CGU AAG CAG UAC UdTdT, respectively.

Maintenance of human melanoma cell line

The human A375 melanoma cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, CRL 1619) (Giard et al., 1973) was obtained from Paul Khavari's group at Stanford University and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Preparation of dual reporter primary A375 melanoma cell line

Lentivirus (vTD147 and vTD171) was prepared, and A375 cells were transduced by spinoculation and sorted as previously described (Hickerson et al., 2011a) in order to generate a cell line in which similar expression levels of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and tdTFP are observed. The resulting cell line expressed both EGFP and tdTFP in over 95% of the cells.

Mice

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with both the National Institutes of Health and Stanford University guidelines. Specifically, xenografted mice were periodically monitored and were euthanized once either or both tumors reached the maximum allowed size.

Preparation and imaging of xenograft model

Doubly transduced human A375 melanoma cells were trypsinized (versene-EDTA) and collected by centrifugation. The cell pellet was washed once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS at 1×107 cells/mL. Cells (1×106 cells in 100 μL PBS) were injected intradermally into the right and left flanks of immunocompromised SCID Hairless Outbred (SHO™) mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) under 2% isofluorane anesthesia. Therapy was begun 12 days after injection of the tumor cells (day 0). Tumor growth was monitored and imaged for fluorescence using the CRi Maestro in vivo imaging system (Caliper, Hopkinton, MA now part of Perkin Elmer, Waltham MA) at regular intervals, beginning prior to therapy (day –2), and continuing for 18 days after the first treatment. EGFP and tdTFP images were taken (using the Maestro software auto-exposure and sequential mode functions) at 10 nm windows from 500–800 nm using excitation filters (445–490 nm and 503–555 nm respectively) and long-pass emissions filters (515 nm and 580 nm respectively). Each fluorescence spectrum was obtained by unmixing the autofluorescence (previously obtained from a nontreated mouse) from the overall spectrum and the data generated were used to create a “cube” image. The average fluorescence signal (counts/second/mm2) was quantified using Maestro software, and tdTFP expression was normalized by EGFP expression per tumor, per time point. Unmixed images were pseudocolored red for tdTFP and green for EGFP. The Maestro Imaging System at Stanford complies with the minimum criteria required to produce reproducible data, specifically: (1) the system is regularly calibrated to the manufacturer's specifications, (2) the same spectral library is used for each imaging session, and (3) the measurement units used were scaled counts per second. Following these procedures insured that the gain remained comparable throughout the course of the study.

Preparation of siRNA/Invivofectamine 2.0 complexes

siRNA–Invivofectamine 2.0 complexes (∼100 nm diameter in size as determined by analysis with a Nanosight LM10 instrument (Nanosight, Wiltshire, UK) were prepared according to manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies). Briefly, 250 μL of 3 mg/mL siRNA was combined with 250 μL complexation buffer (supplied by the manufacturer). Invivofectamine 2.0 reagent (500 μL warmed to 21°C) was added and mixed by vortexing. The mixture was incubated at 50°C for 30 minutes before dialysis into PBS using a 3,500 molecular weight cut-off Float-A-Lyzer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 2 hours at 21°C. The volume of the recovered sample was adjusted to 1.5 mL with PBS, resulting in 0.5 mg/mL complexed siRNA and was stored at 4°C for no longer than 1 week prior to injection.

Intratumoral injection of complexed siRNA

Under 2% isofluorane anesthesia, mice were injected with siRNA–Invivofectamine 2.0 complexes (100 μL of 0.5 mg/mL relative to siRNA) directly into the xenograft tumors. Prior to each siRNA–Invivofectamine 2.0 injection, the mice were intravitally imaged as described above.

Quantitative PCR

Tumors were excised from euthanized mice and divided in 3 similarly sized pieces, 2 of which were immediately frozen in dry ice for RNA extraction, and the remaining tissue sample was prepared for histological analysis as described below. RNA was extracted from excised tumors, reverse transcribed, and analyzed by qPCR as previously reported (Hickerson et al., 2011b). Briefly, total RNA was isolated by mechanical disruption of the tissue in Qiazol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), followed by purification using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed on 0.5–2 μg total RNA using the Superscript 3 First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Life Technologies) with random hexamer priming and on-column DNase treatment. Quantitative PCR was performed using the following gene expression assays (Life Technologies): GL4-fLuc (AIOIV1I, hybridizes to the Luc2 regions of the bicistronic Luc2/tdTFP mRNA), EGFP (forward primer: 5′-TCC GCC CTG AGC AAA GAC; reverse primer: 5′-GAA CTC CAG CAG GAC CAT GTG; and 6FAM-labeled probe: 5′-CCA ACG AGA AGC GC), and human-specific glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Hs99999905_m1).

Histology

Tumor samples were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (O.C.T.) compound, frozen, sectioned (10 μm), and mounted with Histomount (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA) containing 1 μg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as previously described (Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al., 2010). Sections were imaged with a Zeiss Axio Observer inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with GFP, Cyanine 3 (Cy3), and DAPI filter sets.

Rapid amplification of complementary DNA ends analysis

The siRNA cleavage site (designed to cleave the tdTFP reporter mRNA 56 nt downstream of the stop codon) was determined using the GeneRacer kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the RNA linker (5′-CGA CUG GAG CAC GAG GAC ACU GAC AUG GAC UGA AGG AGU AGA AA-3′) was ligated to ∼100 ng of total RNA isolated from excised tumors. Ligated RNA was purified by phenol–chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation with 5 μg glycogen (Life Technologies). mRNA was reverse transcribed using an oligo(dT)-25-mer primer. The resulting complementary DNA (cDNA) was initially PCR-amplified using a gene-specific primer (Rev4: 5′-TGA TTA TCG ATA AGC TTG ATA-3′) designed to anneal 81–101 nt downstream of the stop codon, together with the GeneRacer 5′ primer (5′-CGA CTG GAG CAC GAG GAC ACT GA-3′). A second round of PCR was performed with the same gene-specific primer and the GeneRacer 5′ nested primer (5′-GGA CAC TGA CAT GGA CTG AAG GAG TA-3′). The PCR reaction was analyzed on a 4% agarose gel along with molecular weight markers to determine the size of the amplified fragment.

Results and Discussion

In vivo imaging of fluorescent reporter gene expression allows noninvasive monitoring of siRNA effectiveness over time at the same location in the same animal. Incorporation of an internally controlled reporter gene system into melanoma xenografts would provide a significant advantage over existing methods for more effective screening of efficacy and delivery of RNAi-based therapeutics through in vivo imaging.

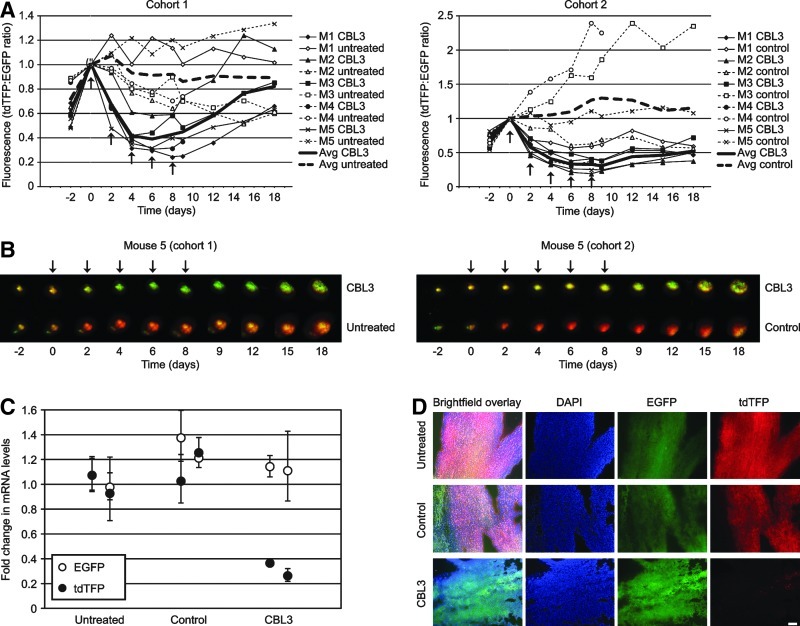

Visualization of siRNA-mediated inhibition of reporter gene expression in a dual fluorescent melanoma xenograft model

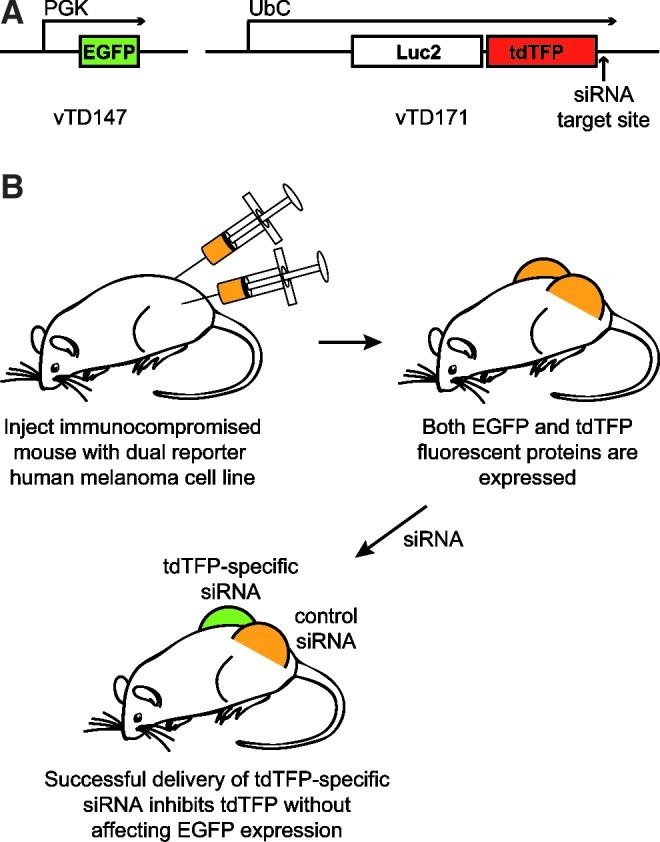

Human A375 melanoma cells were transduced with 2 lentiviral constructs, one of which expresses a fusion reporter gene comprised of a luciferase gene (Luc2) and tdTFP containing the specific CBL3 siRNA target site (Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al., 2009) while the second construct expresses EGFP, which is used as a nontargeted internal control for normalization (Fig. 1). Dual fluorescent reporter A375 melanoma cells were intradermally injected into both the right and left flanks of hairless immunocompromised mice to generate tumors. The mice were divided into two cohorts of 5 mice each. One cohort was treated with CBL3 siRNA complexed with a cationic lipid (see Materials and Methods) in the right flank tumor while the left flank tumor was not treated. The other cohort was similarly treated on the right, but the left flank tumor was treated with complexed, nonspecific control siRNA. As both EGFP and tdTFP signals increase as the tumor size enlarges (regardless of treatment), tdTFP fluorescence signal was normalized to EGFP. Upon treatment with CBL3 siRNA, decreased tdTFP expression (relative to EGFP; Fig. 2A) was observed within the first 48 hours. This trend (i.e., decreased tdTFP relative to EGFP) continued for the duration of the treatment regimen, resulting in 61%±12% and 69%±7% knockdown of the targeted reporter protein in cohorts 1 and 2 respectively. Figure 2B shows overlaid tdTFP and EGFP fluorescence images for a representative mouse (M5) from each cohort demonstrating a decrease in tdTFP expression over the entire visible area of the CBL3-treated tumors. Although EGFP and tdTFP are uniformly expressed in the tissue (see representative microscopic images in Fig. 2D), EGFP detection efficiency was observed to diminish slightly (relative to that of tdTFP) over time. This decrease may be due, at least in part, to growth and increased vascularization of the tumor, both of which result in increased absorption of shorter wavelength light. Variations in tumor size and vascularity may account for some of the mouse-to-mouse variability observed in the nonspecific control siRNA-treated cohort as well (see Fig. 2A). If necessary, this issue could be addressed by using a different control fluorescent protein for normalization, such as Neptune, which fluoresces at a longer wavelength (Ex 600 nm, Em 650 nm) (Lin et al., 2009).

FIG. 1.

Schematic of dual fluorescence reporter mouse model. (A) Lentiviral constructs used to generate the dual reporter cell line. vTD147 expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) under the control of the human phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter. vTD171 expresses tdTFP containing the mRNA sequence from click beetle luciferase (CBL) that is targeted by CBL3 siRNA in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) under the control of the human ubiquitin C (UbC) promoter. (B) Schematic representation of the reporter mouse model in which red fluorescent protein (tdTFP) is targeted by siRNA treatment. Human A375 melanoma cells are transduced with lentiviral constructs expressing vTD147 and vTD171 to generate a dual reporter cell line. Following injection of labeled melanoma cells into immunocompromised mice, the resulting tumors are treated with siRNA. Successful delivery of functional siRNA results in specific inhibition of tdTFP. EGFP should not be affected by siRNA treatment and is therefore used as a normalization control.

FIG. 2.

Specific siRNA (CBL3) inhibits reporter expression in a dual fluorescent reporter melanoma xenograft model. (A) Human A375 melanoma cells expressing EGFP and tdTFP were injected (1×106 cells per injection) into both the right and left flanks of 10 immunocompromised mice, which were divided into two cohorts of 5 mice each. The resulting tumors were intravitally imaged as indicated (see Materials and Methods) to measure EGFP and tdTFP expression levels. The tumors were treated with 0.5 mg/mL siRNA/IVF2.0 complex, containing either nonspecific control or CBL3 siRNA, every 2 days for a total of 5 treatments (indicated by arrows). tdTFP fluorescence was normalized to EGFP fluorescence to account for differences in tumor size. All data were normalized to the “day 0” time point. (B) Overlaid tdTFP and EGFP fluorescence images from each time point are shown for mouse five (M5) from each cohort. These images reveal uniform loss of signal over the surface of the tumor, suggesting knockdown throughout the tissue and not along needle tracks alone. (C) A representative mouse from each cohort (mouse four, M4) was sacrificed on day 9 and duplicate samples were taken from each excised tumor. Total RNA from each sample was isolated and reverse transcribed. Subsequently, Luc2/tdTFP and EGFP cDNA levels (fold change relative to the untreated control) were determined relative to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using the delta delta cycle threshold (ΔΔCT) method. (D) An additional sample of each tumor from mouse 4 (M4) from each cohort was sectioned for analysis by fluorescence microscopy. Representative images are shown. All fluorescent images were collected using the same exposure time to allow effective comparison. Scale bar=100 μm.

Confirmation of siRNA-mediated inhibition by RT-qPCR and histology

On day 9, one mouse from each cohort (M4) was sacrificed to corroborate the inhibition observed by intravital imaging. Tumors were excised from the mouse flank and total RNA was isolated from 2 tissue samples of each tumor. Total RNA was reverse transcribed and analyzed by qPCR for EGFP and Luc2/tdTFP bicistronic mRNA levels (relative to GAPDH) using the delta delta cycle threshold (ΔΔCT) method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Treatment with complexed CBL3 siRNA showed 68%±10% knockdown of the targeted mRNA (Luc2/tdTFP fusion) with no effect on the control mRNA (EGFP), while complexed nonspecific control siRNA had no effect on either transcript (Fig. 2C). These results provide evidence that (1) the targeted mRNA is inhibited throughout the tumor upon treatment with specific siRNA and (2) EGFP levels are unaffected by delivery of CBL3 siRNA (or nonspecific control siRNA) relative to a reference gene (GAPDH).

Approximately one-third of the excised tumor was frozen in O.C.T., sectioned, and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. The untreated and nonspecific control siRNA-treated tumors in Fig. 2D show even distribution of both EGFP and tdTFP throughout the tumor sample analyzed, while treatment with specific siRNA exhibited a marked uniform decrease in tdTFP expression with little or no effect on EGFP expression.

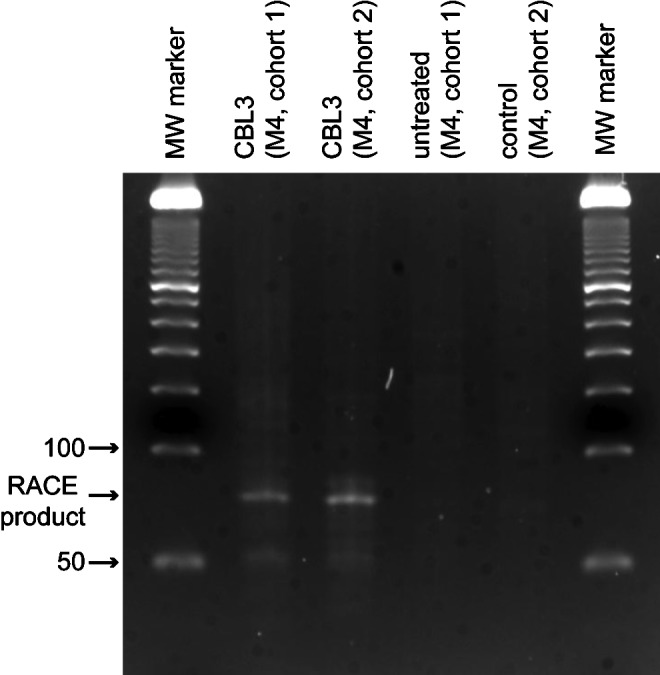

RACE analysis confirms a RNA-induced silencing complex-mediated cleavage mechanism

In order to confirm that siRNA treatment resulted in the predicted target mRNA cleavage, consistent with an RNAi-mediated mechanism [as opposed to an innate immune response through the activation of Toll-like receptors (TLR 3, 7, and 8)] (BEHLKE, 2008), RNA was isolated from CBL3 siRNA-treated tumors and subjected to rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) (Soutschek et al., 2004). siRNA-mediated cleavage is known to occur between nucleotides 10 and 11 from the 5′ end of the antisense strand (Matranga et al., 2005). Figure 3 shows the expected migration of the PCR-amplified cleavage product (the predicted ∼76 base pair PCR amplicon), supporting an RNAi-mediated mechanism.

FIG. 3.

CBL3 siRNA treatment results in reporter mRNA cleavage product consistent with RNA-induced silencing complex-mediated cleavage. Total RNA was isolated from the indicated tumor and subjected to rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) analysis (see Materials and Methods). Following PCR amplification and agarose gel electrophoresis, a band of the predicted size was observed by ethidium bromide staining in the CBL3 siRNA-treated samples.

Conclusion

Here we report a human xenograft melanoma model in which a dual fluorescent reporter model allows effective screening of siRNA delivery methodologies. Specific inhibition of tdTFP reporter protein and mRNA has been demonstrated by direct injection of cationic lipid-complexed siRNA. This xenograft model should be useful for noninvasive systematic screening of putative melanoma target genes, which could help lead to the development of new delivery and/or therapeutic strategies, either alone or in combination with other non-siRNA-based therapies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Heini Ilves, Manny Flores, Pablo Smith, and Rebecca Kaspar for technical assistance and help with preparation of figures. We thank Paul Khavari and Daniel Webster for advice and for providing the human A375 melanoma cell line, Hyejun Ra, Laura Jean Pisani, and Timothy Doyle for in vivo imaging technical support, and Lusijah Rott for help with flow cytometry. We appreciate Yuan Cao, Tycho Speaker, Manny Flores, and Jedediah Humphries for proofreading. This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (R43AR056559-01, RLK) and generous support from the Chambers Family Foundation. EGG is the recipient of a Pachyonychia Congenita Project fellowship. We are grateful for the collegiality and suggestions from Sancy Leachman and other members of the International PC Consortium. We are also grateful for the continued support and encouragement from PC Project and PC patients.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- BEHLKE M. A. Chemical modification of siRNAs for in vivo use. Oligonucleotides. 2008;18:305–319. doi: 10.1089/oli.2008.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNETT J. C. ROSSI J. J. RNA-based therapeutics: current progress and future prospects. Chem. Biol. 2012;19:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINN L. MARKOVIC S. N., et al. Therapy for metastatic melanoma: the past, present, and future. BMC Med. 2012;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIARD D. J. AARONSON S. A., et al. In vitro cultivation of human tumors: establishment of cell lines derived from a series of solid tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1973;51:1417–1423. doi: 10.1093/jnci/51.5.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ-GONZALEZ E. RA H., et al. siRNA silencing of keratinocyte-specific GFP expression in a transgenic mouse skin model. Gene Ther. 2009;16:963–972. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ-GONZALEZ E. SPEAKER T. J., et al. Silencing of reporter gene expression in skin using siRNAs and expression of plasmid DNA delivered by a soluble protrusion array device (PAD) Mol. Ther. 2010;18:1667–1674. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUIDA M. PISCONTE S., et al. Metastatic melanoma: the new era of targeted therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2012;16:S61–S70. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.645807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HICKERSON R. P. FLORES M. A., et al. Use of self-delivery siRNAs to inhibit gene expression in an organotypic pachyonychia congenita model. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011a;131:1037–1044. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HICKERSON R. P. LEACHMAN S. A., et al. Development of quantitative molecular clinical end points for siRNA clinical trials. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011b;131:1029–1036. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSU T. MITRAGOTRI S. Delivery of siRNA and other macromolecules into skin and cells using a peptide enhancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:15816–15821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016152108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACKSON A. L. LINSLEY P. S. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:57–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASPAR R. MCLEAN W., et al. J. Invest. Derm.; Achieving successful delivery of nucleic acids to skin: 6th Annual Meeting of the International Pachyonychia Congenita Consortium; 2009. pp. 2085–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUDCHADKAR R. PARAISO K. H., et al. Targeting mutant BRAF in melanoma: current status and future development of combination therapy strategies. Cancer J. 2012;18:124–131. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31824b436e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KWON S. Y. MILLER S. J. Mohs surgery for melanoma in situ. Dermatol. Clin. 2011;29:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.01.001. vii–viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEACHMAN S. A. HICKERSON R. P., et al. First-in-human mutation-targeted siRNA phase 1b trial of an inherited skin disorder. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:442–446. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN M. Z. MCKEOWN M. R., et al. Autofluorescent proteins with excitation in the optical window for intravital imaging in mammals. Chem. Biol. 2009;16:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIVAK K. J. SCHMITTGEN T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATRANGA C. TOMARI Y., et al. Passenger-strand cleavage facilitates assembly of siRNA into Ago2-containing RNAi enzyme complexes. Cell. 2005;123:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONZON J. G. DANCEY J. Targeted agents for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Onco. Targets Ther. 2012;5:31–46. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S21259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOUTSCHEK J. AKINC A., et al. Therapeutic silencing of an endogenous gene by systemic administration of modified siRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature03121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]