Abstract

Antibodies have emerged as important therapeutics for cancer. Recently, it has become clear that antibodies possess multiple clinically relevant mechanisms of action. Many clinically useful antibodies can manipulate tumour-related signalling. In addition, antibodies exhibit various immunomodulatory properties and, by directly activating or inhibiting molecules of the immune system, antibodies can promote the induction of anti-tumour immune responses. These immunomodulatory properties can form the basis for new cancer treatment strategies.

Introduction

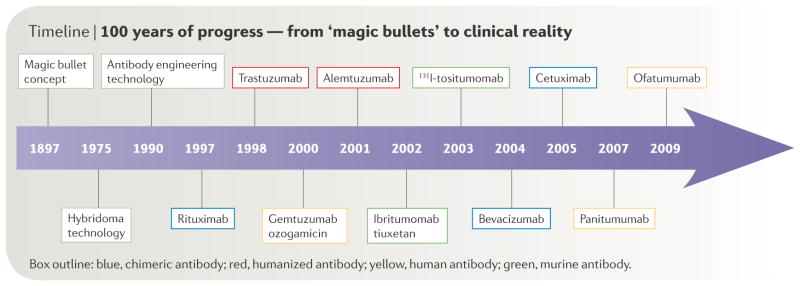

The concept of using antibodies to selectively target tumours was proposed by Paul Ehrlich over a century ago1. The advent of hybridoma technology in 1976 enabled the production of monoclonal antibodies2. Due to their murine origins, these monoclonal antibodies typically were immunogenic in humans and possessed poor abilities to induce human immune effector responses, thereby limiting their clinical applicability. Later advances in antibody engineering provided flexible platforms for the development of chimeric, humanized and fully human monoclonal antibodies which satisfactorily addressed many of these problems (FIGURE 1).

Figure 1.

100 years of Progress-From “Magic Bullets” to Clinical Reality.

Over the past decade, the effectiveness of antibodies in treating patients with cancer has been realized with increasing frequency (TABLE 1). Many of these antibodies are specific for antigens expressed by the tumour itself. Antibodies conjugated to radioisotopes or chemotherapeutic drugs have shown therapeutic efficacy primarily in hematological malignancies, whereas unconjugated antibodies targeting growth factor receptors, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2, also known as ERBB2/NEU) are commonly used for the treatment of non-leukaemic cancers. In addition to antibodies that target tumour antigens, antibodies that target the tumour microenvironment slow tumour growth by enhancing host immune responses to self-tumour antigens or curtailing pro-tumourigenic factors produced in the tumour stroma.

Table 1.

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies approved for use in oncology

| Generic name (trade name) | Target | Antibody Form | Cancer Indication | REF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconjugated antibodies | ||||

| Rituximab (Rituxan) | CD20 | Chimeric IgG1 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 74, 105 |

| Trastuzumab (Herceptin) | HER2 | Humanized IgG1 | Breast cancer | 19, 72 |

| Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) | CD52 | Humanized IgG1 | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 58 |

| Cetuximab (Erbitux) | EGFR | Chimeric IgG1 | Colorectal cancer | 13, 106 |

| Bevacizumab (Avastin) | VEGF | Humanized IgG1 | Colorectal, breast, lung cancer | 71, 107, 108 |

| Panitumumab (Vectibix) | EGFR | Human IgG2 | Colorectal cancer | 109 |

| Ofatumumab (Arzerra) | CD20 | Human IgG1 | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 110 |

| Immunoconjugates | ||||

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Myelotarg) | CD33 | Humanized IgG4 | Acute myelogenous leukemia | 111 |

| 90Y-Ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) | CD20 | Murine | Lymphoma | 112 |

| Tositumomab and 131I-tositumomab (Bexxar) | CD20 | Murine | Lymphoma | 113 |

Here, we highlight important features of anti-tumour antibodies, with a focus on how such antibodies promote immune effector mechanisms to control tumour growth.

Structural and functional features of antibodies

Antibody structure

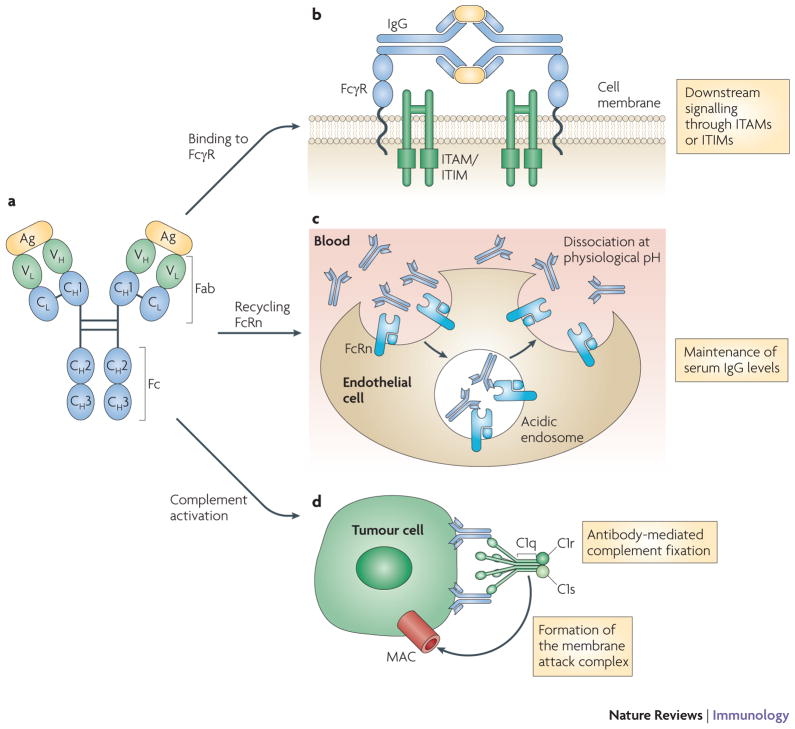

Antibodies are grouped into five classes based on the sequence of their heavy chain constant regions: IgM, IgD, IgG, IgE and IgA. Of the five classes, IgG is the most frequently used for cancer immunotherapy and is the focus of this Review. Antibodies can be subdivided into two distinct functional units: the fragment of antigen binding (Fab) and the constant fragment (Fc). The Fab contains the variable region, which consists of three hypervariable complementarity determining regions (CDRs) that form the antigen binding site of the antibody and confer antigen specificity. Antibodies are linked to immune effector functions via the Fc fragment, which is capable of initiating complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), binding to Fc γ-receptors (FcγR) and binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) (FIGURE 2).

Figure 2. IgG structure and function.

IgG is composed of two heavy and light chains consisting of constant regions, which contribute to the Fc domain, and variable regions, which contribute to antigen specificity (panel A). Antigen coated with IgG can bind Fc receptors and initiate signalling through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) or immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inibitory motifs (ITIMs) (panel B). IgG can bind neonatal Fc receptors (FcRn) on endothelial cells to maintain serum IgG levels (panel C) or bind to tumour cells and recruit C1q to initiate the complement cascade, resulting in tumour cell lysis by the membrane attack complex (MAC) (panel D).

Antibody functions

Subclasses of IgG, most notably IgG1 and IgG3, are potent activators of the classical complement pathway. The binding of two or more IgG molecules to the cell surface leads to high-affinity binding of C1q to the Fc domain, followed by activation of C1r enzymatic activity and subsequent activation of downstream complement proteins. The result of this cascade is the formation of pores by the membrane attack complex (MAC) on the tumour cell surface and subsequent tumour cell lysis. In addition, production of the highly chemotactic complement molecules C3a and C5a leads to the recruitment and activation of immune effector cells, such as macrophages, neutrophils, basophils, mast cells and eosinophils3. These properties have been extensively reviewed elsewhere4.

FcγRs can transduce activating signals through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs), or deliver inhibitory signals through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs). The major inhibitory FcγR is the single chain FcγRIIB (also known as CD32) whereas most Fc-dependent stimulatory signals are transduced by FcγRI (also known as CD64) and FcγRIIIA (also known as CD16A), both of which require an accessory ITAM-containing γ-chain to initiate signal transduction5. FcγRI is a high-affinity receptor expressed by macrophages, DCs, neutrophils and eosinophils5. FcγRIIIA is the primary activating FcγR expressed by natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages and mast cells, and is required for NK cell-mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)5. FcγRIIIB (CD16B) is a glycophosphatidyl inositol (GPI)-anchored protein that, unlike FcγRIIIA, does not contain the common gamma chain and is exclusively expressed on human neutrophils.

The binding of IgG antibodies to tumour cells enables the recognition of these targets by immune effector populations that express Fcγ receptors, such as NK cells, neutrophils, mononuclear phagocytes and dendritic cells. Cross-linking of FcγRs on these cells promotes ADCC and tumour cell destruction (FIGURE 2). Following tumour cell lysis, antigen-presenting cells can present tumour-derived peptides on MHC class II molecules and promote CD4+ T cell activation. Additionally, in a process known as cross-presentation, tumour-derived peptides can be presented on MHC class I molecules, resulting in activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (see below).

FcRn are structurally distinct from FcγR, and are related to MHC class I molecules. They bind both IgG antibodies and albumin in a pH-dependent manner, with optimal binding occurring at acidic pH. The role of FcRn in the passive transfer of maternal humoral immunity from mother to foetus has been well characterized6. FcRn also plays an important role in the maintenance of serum IgG and can contribute to the long half-life seen with this isotype (FIGURE 2). FcRn expressed on the vascular endothelium can bind IgG by its Fc domain, returning it to the circulation, or protecting it from transcytotic lysosomal catabolism en route to the lymphatics6. FcRn–IgG interactions could be useful therapeutically, and efforts to manipulate the binding of monoclonal IgG to FcRn to enhance the serum half-life of IgG are underway7. In addition to regulating the serum half-life of human IgG, FcRn may also contribute to antibody-mediated antigen presentation8.

Targeting tumour cells and the tumour microenvironment

Many of the tumour-expressed targets for therapeutic antibodies are growth factor receptors that show increased expression during tumourigenesis. By blocking ligand binding and/or signalling through these receptors, monoclonal antibodies may serve to normalize growth rates, induce apoptosis and/or help sensitize tumours to chemotherapeutic agents9. In addition, antibodies that target the tumour microenvironment and inhibit processes such as angiogenesis have shown therapeutic promise.

Blockade of ligand binding and signalling perturbation

Members of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family, including EGFR (also known as ERBB1), HER2 (also known as ERBB2), HER3 (also known as ERBB3), and HER4 (also known as ERBB4), are frequently overexpressed in solid tumours and are the target of many currently used therapeutic antibodies. Cetuximab, a chimeric EGFR-specific IgG1 monoclonal antibody, functions by preventing binding of activating ligand10 and by preventing receptor dimerization, a critical step for initiating EGFR-mediated signal transduction11. Panitumumab, a fully humanized IgG2 isotype antibody that is specific for EGFR, works by a similar mechanism as cetuximab12, but unlike cetuximab, it does not promote ADCC. Both of these agents have been used as second- or third-line therapy for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer12. Cetuximab, in contrast to the EGFR-specific antibody panitumumab, is often used in combination with other chemotherapeutic regimens. Combining cetuximab therapy with folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) chemotherapy has been shown to prolong progression-free survival in patients with metastatic colon cancer whose tumours harbour wild type v-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sacrcoma viral oncogene homologue (KRAS) alleles13. In contrast, these therapeutic agents are ineffective when KRAS is mutated13. A fully human anti-EGFR antibody, Necitumumab (IMC-11F8) was recently described and shown to be well tolerated in patients with advanced solid malignancies14.

In addition to targeting the complete form of EGFR, efforts are underway to target a truncated form of the receptor, EGFRvIII (an in frame deletion of exons II–IV), which is found in patients with glioblastoma, head and neck cancer and non-small cell lung carcinoma15. A phase I study using the EGFRvIII-targeting monoclonal antibody 806, which targets EGFR as it dimerizes following ligand binding16, showed good antibody penetration of tumour tissue and no significant toxicities in patients with metastatic disease17.

In contrast to EGFR, HER2 has no known ligand and antibodies targeting this receptor function primarily to inhibit receptor homo- and hetero-dimerization and internalization, rather than by blocking ligand-binding18. HER2 is gene-amplified and overexpressed in approximately 30% of invasive breast cancers and is overexpressed, although rarely gene-amplified, by some adenocarcinomas of the lung, ovary, prostate and gastrointestinal tract18. Trastuzumab, a humanized IgG1 antibody, is used for the treatment of invasive breast cancer that exhibits gene amplification and overexpression of HER2. Trastuzumab monotherapy showed a 35% objective response rate in patients with metastatic breast cancer not previously receiving chemotherapy19. The mechanisms of action by which trastuzumab exerts its anti-tumour effects include inhibition of receptor dimerization, endocytic destruction of the receptor and immune activation20. Another HER2-directed antibody, pertuzumab, binds at a distinct site from trastuzumab and sterically inhibits receptor dimerization21. Synergistic anti-tumour effects of combination therapy with pertuzumab and trastuzumab have been reported in pre-clinical models22.

A new HER3-targeted antibody, MM-121, is currently being developed and has been shown to specifically bind HER3, inhibit growth of mouse xenograft tumours and block heregulin-dependent signalling through the protein kinase AKT, leading to tumour cell death23. Efforts to target HER4 are underway; however, the biological significance of HER4 expression in cancer is poorly understood. HER4 has been reported to be both upregulated and downregulated in cancer, presumably due to the presence of many isoforms and its prognostic value is yet to be determined24. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody targeting selected HER4 isoforms resulted in decreased proliferation of two tumour cell lines; mechanistically, this was due to inhibition of HER4 phosphorylation and cleavage, and the downregulation of HER4 expression24.

Targeting the tumour microenvironment

Strategies to target critical events within the tumour microenvironment have demonstrated therapeutic benefit in preclinical and clinical settings. For example, many solid tumours express vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which binds to its receptor on the vascular endothelium to stimulate angiogenesis. Bevacizumab, a VEGF-specific humanized monoclonal antibody, blocks binding of VEGF to its receptor and is approved for the treatment of breast, colorectal and non-small cell lung cancer in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy25. Efforts to target VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) by other molecules are also underway. Ramucirumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against VEGFR2, has been shown to inhibit growth of human xenografts in mice26. A multi-center phase III clinical trial investigating the effect of combination therapy with ramucirumab and the chemotherapy agent docetaxel in women with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer is currently underway27. Similarly, efforts to target VEGFR1 with the fully human antibody IMC-18F1 are currently underway and have shown preclinical promise28.

The increasing therapeutic use of bevacizumab has led to an increase in bevacizumab-resistant tumours due to upregulation of other proangiogenic mediators such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). PDGF-receptor (PDGFR)-signalling is important in maintaining the endothelial support system, which stabilizes and promotes the growth of new blood vessels29. Blockade of PDGFR-signalling via a PDGFRβ-specific human antibody has been shown to synergize with anti-VEGFR2 therapy in preclinical models and suggests the utility of anti-PDGFRβ therapy in the setting of bevacizumab resistance30.

Targeting immune cells

In addition to directly targeting tumour cells, numerous antibody-based therapeutic strategies have been developed to target cells of the immune system with the goal of enhancing anti-tumour immune responses. Here, we consider the targeting of immunoregulatory co-receptors, antibody-based strategies aimed at reversing tumour-mediated immunosuppression and Fc domain modulation to alter the specificity of Fc receptor-targeting and activation.

CD40 is a member of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (TNFR) family and is expressed by B cells, DCs, monocytes and macrophages. Engagement of CD40 on antigen-presenting cells leads to the upregulation of costimulatory molecules, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and facilitates cross-presentation of antigens31. Many tumours have been shown to express CD40, including carcinomas of the ovary, nasopharynx, bladder, cervix, breast and prostate, and the engagement of CD40 can lead to a direct anti-tumour effect in some tumours in vivo32. In one study, the effect of a fully human anti-CD40 agonist monoclonal IgG2 (CP-870,893) was assessed in 29 patients with advanced solid tumours. The results demonstrated four partial responses (all patients with melanoma), with one complete resolution33. A second anti-CD40 antibody, dacetuzumab (SGN-40), is a humanized IgG1 that can induce tumour cell apoptosis as well as ADCC, and was recently shown to exert its anti-tumour effects by inducing Fc-mediated phagocytosis of tumour cells by macrophages34. Early clinical trials suggest that dacetuzumab exhibits promise in the treatment of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma35.

CTLA4, a homologue of CD28, is a negative regulator of T cell activation that binds CD80 (also known as B7.1) and CD86 (also known as B7.2) with higher affinity than CD28. CTLA4 blockade enhanced rejection of CD86-negative tumours, implying that this was not through direct effects on the tumour, and reduced the growth of established tumours36. Furthermore, CTLA4 blockade resulted in protection from secondary tumour challenge, suggesting the development of immunological memory36. Subsequent studies showed that treatment with a CTLA4-specific antibody can prevent and reverse antigen-specific CD8+ T cell tolerance in a CD4+ T cell-dependent manner37. Recent work has revealed that enhancement of T cell effector functions, combined with the inhibition of regulatory T cells (TREG), might be responsible for the anti-tumour effects of CTLA4 blockade38. These preclinical data show that anti-CTLA4 treatment can enhance adaptive immunity and promote tumour regression.

Two CTLA4-specific monoclonal antibodies have been studied in clinical trials. Tremelimumab (IgG2 isotype) and ipilimumab (IgG1 isotype) can induce delayed disease regression in patients with metastatic melanoma39. In addition, ipilimumab is being investigated as a treatment option for men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer40. On a cautionary note, dose-dependent, immune-related toxicity has been reported with CTLA4-specific antibodies; these side-effects include rash, vitiligo, diarrhoea, colitis, nephritis with azotemia, hypophysitis and hepatitis41. Antibodies targeting OX40, B7-H1 and CD137 have also shown pre-clinical promise and are described in Table 2, but have not yet undergone extensive clinical testing.

Table 2.

Antibodies targeting immune cells

| Target | Antibody name | Expression | Function | Agonist/Antagonist | Effect of Antibody treatment in preclinical studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD40 | Dacetuzumab, CP-870,893 | DCs, B cells, monocytes, macrophages | DC maturation, germinal center formation, isotype switch, affinity maturation | Agonist | Apoptosis in some tumours, expansion of tumour specific CD8+ T cells 33. |

| CTLA-4 | Tremilimumab, Ipilimumab | Activated T cells | inhibition of T cell proliferation | Antagonist | Tumour rejection, protection from re-challenge36. Enhanced tumour-specific T cell responses37. |

| OX40 | OX86 | Activated T cells | T cell expansion, maintenance of memory cells | Agonist | Antigen-specific CD8+ T cell expansion at tumour site, reduction in myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC), TGFβ, and TREG. Enhanced tumour rejection 114. |

| PD-1 | CT-011 | Activated lymphocytes | Negative regulator of lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production | Antagonist | Maintenance and expansion of tumour specific memory T cells, NK cell activation 115 |

| CD137 | BMS-663513116 | Activated T cells, Treg, NK cells, NKT cells, DC, neutrophils, monocytes 117 | T cell expansion, CD8+ survival, NK proliferation and IFN-γ production | Agonist | Regression of established tumours, expansion and maintenance of CD8+ T cell117. |

| CD25 | Daclizumab | Activated T cells | IL-2R α chain. T cell proliferation, expressed on TREG | Antagonist | Transient depletion of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Treg48. Enhanced tumour regression and T cell expansion118. |

Targeting immunosuppressive tumour microenvironments

Tumour cells and the surrounding stroma can produce profoundly immunosuppressive cytokines and growth factors. Among the best characterized of these factors is transforming growth factorβ (TGFβ), which can inhibit T cell activation, differentiation, and proliferation42. TGFβ has been shown to promote tumour escape from the immune system, and high plasma levels of TGFβ correlate with a poor outcome in various malignancies42. GC-1008 is a fully human anti-TGFβ antibody that binds to all three isoforms of TGFβ43. Recruitment is currently underway to a clinical trial GC-1008 in patients with metastatic kidney cancer or malignant melanoma (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00899444).

The production of immunosuppressive factors such as TGFβ can result in the accumulation of suppressive CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ TREG cells44, which is associated with poor clinical outcomes45. Treatment with CD25-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete TREG cells has shown remarkable potential in pre-clinical models of various malignancies46 and has been shown to suppress tumour formation and metastasis in a mouse model of breast cancer47. Clinically, the humanized IgG1 CD25-specific monoclonal antibody daclizumab is well tolerated, resulted in depletion of TREG cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer and may synergize with peptide vaccines targeting human telomerase reverse transcriptase and the anti-apoptotic protein survivin48. However, anti-CD25 therapy could potentially deplete effector T cells that have upregulated CD25 upon activation. In addition, further studies are required to understand the role of CD25-negative TREG in the setting of cancer48.

Fc domain modulation

As discussed below, numerous pre-clinical studies suggest that ADCC is a major mechanism of action of several monoclonal antibodies used in cancer immunotherapy. Efforts to modify the Fc domain primary structure using computational and high-throughput screening have resulted in Fc domains with higher affinity for FcγRIIIA and an enhancement of ADCC49. The new CD20-specific antibodies, ocrelizumab and AME-133, both contain mutated Fc domains resulting in enhanced ADCC compared to rituxumab50. Modification of Fc domain oligosaccharide content provides another mechanism for enhancing ADCC. Most of the currently used therapeutic antibodies are highly fucosylated due to the nature of the cell lines used for manufacturing. However, antibodies with defucosylated oligosaccharides display a significant enhancement in ADCC in vitro and enhanced in vivo anti-tumour activity50. Phase I trials of defucosylated antibodies specific for CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4), which is expressed by some lymphoid neoplasms and used by TREG cells to facilitate their migration to the tumour microenvironment45, have shown promise and early data suggest efficacy at significantly lower doses than conventional therapeutic antibodies50.

How Do Anti-Cancer Monoclonal Antibodies Really Work?

Many mechanisms have been proposed to explain the clinical anti-tumour activity of unconjugated tumour antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies. As discussed above, the ability of some antibodies to disrupt signalling pathways involved in the maintenance of the malignant phenotype has received wide attention. However, the ability of antibodies to initiate tumour-specific immune responses has been less well recognized. Here, we describe these mechanisms and discuss the potential for using antibodies to manipulate the host immune response to tumours. We focus on three mechanisms: ADCC, complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and the induction of adaptive immune responses.

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

Several studies have established the importance of Fc-FcγR interactions to the in vivo anti-tumour effects of certain monoclonal antibodies in murine models and clinical trials. A seminal paper demonstrated that the anti-tumour activities of trastuzumab and rituximab were reduced in FcγR-deficient mice as compared with wild-type mice51. The role of FcγR in the anti-tumour response has been further supported by the finding that polymorphisms in the gene encoding FcγRIII, which lead to higher binding of antibody to FcγRIII, are associated with high response rates to rituximab in patients with follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma52. A separate study that compared clinical responses to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma implicated both FcγRIII and FcγRIIB as playing a role in responses to rituximab53. More recent findings show that FcγR polymorphisms are associated with clinical responses to other antibodies, including trastuzumab54 and cetuximab55. Patients with breast cancer who responded to trastuzumab with complete or partial remission have been found to have a higher capability to mediate in vitro ADCC in response to trastuzumab than did patients whose tumours failed to respond to therapy54.

ADCC enhancement through Fc domain modification has shown promise in the development of next generation antibodies. For example, a CD19-specific antibody with increased FcγRIIIA binding affinity mediated significantly increased ADCC compared to its parental antibody and rituximab56. The in vivo infusion of this high affinity antibody efficiently cleared malignant B cells in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis)57.

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity

Most clinically approved monoclonal antibodies that mediate ADCC also activate the complement system. However, alemtuzumab, which recognizes CD52 expressed on mature B and T cells, activates human complement and demonstrates anti-tumour activity in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but does not mediate ADCC58. The relationship between complement activation and therapeutic activity is also suggested from studies with several clinically approved monoclonal antibodies. The anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab has been found to be dependent in part on CDC for its in vivo efficacy. In a preclinical therapy model, anti-tumour protection by rituximab was completely abolished in C1q knockout mice59. It was also demonstrated that depletion of complement reduced the therapeutic activity of rituximab in a xenograft model of human B cell lymphomas60. The importance of rituximab-mediated CDC is supported by the demonstration that genetic polymorphisms in the C1qA gene correlate with clinical response to rituximab therapy in patients with follicular lymphoma61.

Optimization of antibody-based complement activities can enhance anti-tumour activity. For example, a CD20-specific antibody, ofatumumab, which mediates improved CDC was approved for the treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in 2009. This fully human antibody binds a different epitope than rituximab with more optimal binding kinetics and induces potent tumour cell lysis through improved activation of the classical complement pathway62. An initial study in patients with refractory CLL showed a 50% response rate to ofatumumab, suggesting a higher efficacy than rituximab in the setting of CLL, although this higher response rate may not solely be due to enhanced CDC62. Several studies indicate that both CDC and ADCC can contribute to monoclonal antibody-induced tumour cell lysis. However, the relative clinical importance of each mechanism, and whether the mechanisms are synergistic, additive or antagonistic, remains uncertain. For example, in a mouse model of lymphoma, depletion of complement enhances NK cell activation and ADCC, thus improving the efficacy of the antibody63.

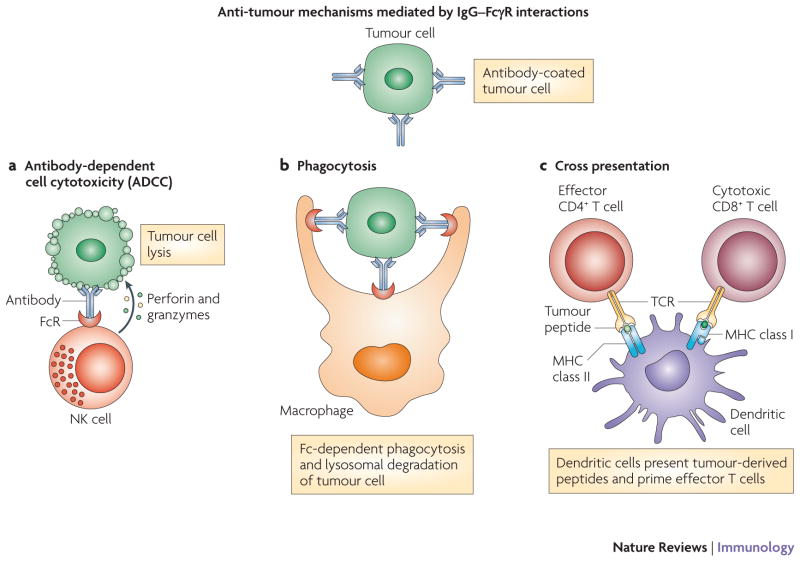

Induction of T cell immunity through cross-presentation

Early research on the anti-tumour effects of therapeutic antibodies focused on the potential value of passive immunotherapy provided through ADCC and CDC. Interestingly, studies have suggested that the maximal clinical benefit of rituximab is not apparent until months after initiation of therapy, suggesting a role for the adaptive immune system in mediating the long-term benefit of monoclonal antibodies64. There is growing evidence to suggest a role for cross-presentation in the induction of adaptive immune responses following antibody therapy. DCs are capable of presenting peptides from engulfed apoptotic cells on MHC class I molecules to elicit antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses65. In one study, DC loaded with killed allogeneic melanoma cells induced cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTL) that were specific for various melanoma antigens and killed melanoma cell lines in vitro66. Another group reported a similar finding using a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line67. Induction of adaptive immunity was linked to antibody therapy in a study showing that tumours coated with antibodies were able to enhance cross-presentation of tumour antigens in a FcγR-dependent fashion68, and blockade of the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIB was shown to enhance cross-presentation by DCs69. ADCC mediated by monoclonal antibodies may trigger cross-presentation by DCs and lead to adaptive immune responses, as DCs can engulf the resultant apoptotic tumour cells and subsequently present tumour antigens on MHC class I and II molecules (FIGURE 3). This dual presentation leads to direct tumour cytotoxicity by CTLs and the generation of CD4+ T cells, which can prime B cells for the production of tumour-specific host antibodies. In addition, cross-presentation may be mediated by phagocytosis of dying antibody-coated tumour cells through FcγR68. It is important to note that DC presentation of engulfed tumour antigens can lead to either immunity or tolerance based on the tumour microenvironment. Accordingly, strategies aimed at targeting tolerizing factors in the microenvironment may synergize with tumour-directed antibody therapy by enhancing cross-presentation and breaking local tolerance.

Figure 3. Anti-tumour mechanisms mediated by IgG–FcγR interactions.

Antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC) is initiated by the recognition of IgG-coated tumours by FcγRs, which are expressed by effector immune cells such as NK cells, macrophages, and neutrophils. These interactions lead to ADCC and tumour cell apoptosis, which is mediated by the delivery of perforin and granzymes to the tumour cell (panel A). The IgG-coated apoptotic tumour cells can bind Fc receptors on phagocytes and initiate Fc-dependent phagocytosis, leading to the lysosomal degradation of the tumour cell (panel B). Peptides derived from lysosomal degradation of tumour cells can be loaded onto MHC class II molecules, leading to the activation of CD4+ helper T cells. In addition to CD4+ T cell activation, dendritic cells can cross-present tumour cell antigens and prime cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (panel C).

Combination approaches

The anti-tumour efficacy of many therapeutic antibodies can be enhanced by their use in combination with other immunomodulatory approaches such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted-therapy agents, vaccines or other immunomodulators.

Combinations with cytotoxic chemotherapy

Although chemotherapy has been traditionally thought to be immunosuppressive, recent evidence has challenged this view70. Bevacizumab in combination with FOLFIRI resulted in a 10.6 month median duration of progression free survival compared to 6.2 months with FOLFIRI alone71. Similarly, trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy showed a 50 percent objective response rate compared to 35 percent with chemotherapy alone in patients with metastatic breast cancer72. One small study found that combined treatment with trastuzumab and paclitaxel induced humoral and cellular anti-HER2 immune responses that were associated with favorable clinical outcomes in patients with advanced breast cancer73. The induction of HER2-specific CD4+ T cells and humoral immune responses indicated that an adaptive immune against HER2 was induced by this treatment. Similar benefits are also well documented with rituximab, where inclusion of rituximab in a standard chemotherapy regimen resulted in an overall response rate of 76 percent compared to 63 percent with chemotherapy alone in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma74. The benefit of adding rituximab to chemotherapeutic regimens was also reported in follicular and mantle cell lymphoma75.

Combinations with radiation

Although radiation therapy has long been viewed as being immunosuppressive, it has been hypothesized that radiation can result in enhanced anti-tumour immunity76. Based on this understanding, investigators have begun to combine radiation and antibody therapies. A phase III clinical trial showed that combining the EGFR-targeting antibody, cetuximab, to a primary radiotherapy regimen significantly improved the overall 5 year survival of patients with advanced squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck, compared with radiotherapy alone77. The safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant bevacizumab, which targets VEGF, with chemoradiotherapy in advanced rectal cancer was evaluated in a phase I/II clinical study and appeared to be safe and potentially effective78. The concentrations of VEGF and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 in the blood of these patients significantly correlated with clinical outcomes. However, these studies have not tested the possibility that combinations of radiation with antibody therapy can induce host-protective adaptive immune responses. In a phase II clinical study, which reported the use of a recombinant cancer vaccine combined with standard definitive radiotherapy in patients with localized prostate cancer, it was shown that combination treatment can generate the development of T cells directed against other tumour-associated antigens not present in the vaccine79. Recent evidence suggests that radiation therapy might activate innate immune effector cells through toll-like receptor (TLR)-dependent mechanisms, thereby augmenting the adaptive immune response to cancer80.

Combination with immunomodulators

Improved understanding of the cytokines involved in modulating effector cells of the innate immune system, together with recent understanding of NK cell recognition and killing of target cells, have provided a basis for the rational investigation of immunoregulatory cytokine combinations in the treatment of specific cancers. Cytokines such as IL-281 and IFNγ82 have been shown, both in murine models and clinical trials, to enhance ADCC by stimulating or expanding NK cells, macrophages and monocytes in vivo. In a phase II clinical trial of combined therapy with IL-2 and rituximab, IL-2 expanded the number of FcR-bearing cells in vivo and enhanced in vitro ADCC by rituximab81. The effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mediated neutrophil stimulation on rituximab activity have been studied in a phase I/II trial in patients with low-grade lymphoma83. Although the overall response rate was comparable to that reported for rituximab monotherapy, remission duration in this pilot phase II study was remarkably long. A recent phase 1 study demonstrated the feasibility of integrating IL-2 into a regimen of ch14.18(an antibody targeting ganglioside GD2, a cell surface antigen highly expressed on human neuroblastomas) plus GM-CSF in an effort to boost effector immune responses84.

Combining targeted therapy agents

Combination therapy employing monoclonal antibodies and small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), which act to block activation of intracellular signalling in tumour cells or stromal cells following receptor engagement, has been proposed as an approach to enhance clinical efficacy through more effective cancer-specific signalling perturbation with concurrent activation of immune effector mechanisms. The effect of combining SU6668 (a VEGFR2-, PDGFRβ– and FGFR1 TKI) with a mouse CD86–IgG fusion protein, which provides a stimulatory signal to CD86, was tested in pre-clinical mouse models. These studies demonstrated enhanced anti-tumour and anti-metastatic responses, as well as an increase in tumour-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, compared with monotherapy85. Similarly, when the effect of combining cetuximab with gefitinib (an EGFR TKI) was investigated in preclinical models, combination treatment resulted in permanent regression of large tumours at suboptimal doses, whereas cetuximab monotherapy induced transient regression only at the highest doses86. Combination therapy provided superior inhibition of EGFR-signalling, greater inhibition of cell proliferation and vascularization, and enhanced apoptosis86. A phase I clinical trial demonstrated the feasibility of gefitinib and cetuximab combination therapy in patients with refractory non-small cell lung cancer87. Recent work has shown enhanced efficacy of combination therapy using lapatinib, a small molecule HER2-specific TKI, and trastuzumab compared to monotherapy88. In addition to its TKI activity, lapatinib promoted the formation of inactive HER2 homodimers at the plasma membrane, resulting in enhanced trastuzumab-mediated ADCC88. A recent phase III clinical trial demonstrated that trastuzumab and lapatinib combination therapy improved progression free survival compared to lapatinib monotherapy in patients with HER2 positive, trastuzumab refractory metastatic breast cancer89.

Combinations with vaccines

Given the evidence suggesting that monoclonal antibody therapy can have both direct and indirect effects on the adaptive immune response, combining antibody therapy with vaccination strategies may prove to be efficacious. Using irradiated GMCSF-producing B16 melanoma cells as a vaccination strategy, it was shown that the addition of anti-CTLA4 antibody was more effective at eradicating established B16 tumours compared to vaccination alone90. This enhanced anti-tumour effect was dependent on CD8+ T cells and NK1.1+ cells90. Similarly, in a mouse tumour model induced by the subcutaneous injection of a colon carcinoma, the addition of the TGFβ-specific antibody ID11 to an irradiated tumour cell vaccine significantly enhanced anti-tumour activity in a CD8+ T cell-dependent manner91. Addition of TGFβ-specific antibody to a peptide vaccine was found to increase the number and lytic activity of tumour antigen-specific CTLs, but had no effect on the numbers of TREG or TH17 cells92. Therefore pre-clinical data support the idea of combining antibodies that target the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment with vaccination. Similarly, studies combining antibodies specific for tumour antigens, such as trastuzumab, with peptide-based vaccines that stimulate HER2-specific T cell responses are underway and have shown initial clinical promise93.

Other Structures

Advances in antibody engineering have generated novel antibody constructs that permit the testing of new antibody based therapy strategies. Bispecific antibodies simultaneously targeting epitopes on tumour as well as immune effector cells have long been shown to have equivalent or superior potency as compared to their IgG counterparts. However, they showed limited clinical efficacy largely attributed to host toxicities caused by concurrent T cell costimulation and short half lives. BiTE molecules, which employ a new format of bispecific anti-CD3 antibody, are formed by linking two Fv fragments using flexible linkers. BiTE molecules show enhanced tumour cell lysis, high protein stability and efficacy at low T cell to target cell ratios94. MT110, a BiTE molecule specific for human epithelial cell adhesion molecule (Ep-CAM) and CD3, has shown anti-tumour efficacy in a mouse xenograft model95 and is currently being studied in a phase I clinical trial (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00635596). Additional advances in protein engineering have focused on equipping non-Ig family proteins with novel binding sites and are collectively called engineered protein scaffolds. In contrast to antibodies, scaffolds are usually comprised of monomeric proteins or a stably folded extramembrane domain of a surface receptor that is highly stable and compatible with high yield expression systems96. Examples of engineered protein scaffolds include designed ankyrin repeat domains (DARPins) and Adnectins, which are composed of the 10th extracellular domain of fibronectin III that folds to adopt an Ig-like structure. A VEGFR-2 adnectin was recently reported to possess anti-tumour activity against human tumour xenografts97.

Future Prospects

FcγRs provide the key link between therapeutic antibodies and the cellular immune system, and enable monoclonal antibodies to induce adaptive immune responses. The magnitude and quality of the innate immune responses induced by ADCC might have an impact on the ensuing adaptive immune response. ADCC-inducing approaches therefore offer a promising basis to improve antibody efficacy. New insights from animal models and clinical trials suggest a rationale for ADCC-based combination therapy, approaches that promote antigen presentation (for example, Toll-like receptor agonists98), co-stimulation (for example, CTLA-4 antibody) and T cell activation or expansion (for example, IL-281). Furthermore, antibody structures can be modified to selectively engage activating rather than inhibitory FcγRs. Fusion antibodies with immunostimulatory motifs that induce and amplify antigen presentation and costimulation have also shown promise99. However, new methods and more investigation are still needed to more accurately detect and monitor immune responses directed against tumour antigens in vivo.

Conclusion

The past century has witnessed the evolution of the ‘magic bullet’ from concept to clinical reality. The attributes of target specificity, relatively low toxicity as well as the ability to activate the immune system suggest the continuing promise of therapeutic antibodies. Therapeutic antibodies currently provide clinical benefit to patients with cancer and have been established as ‘standard of care’ agents for several highly prevalent human cancers. The next generation of unconjugated antibody therapies will undoubtedly yield many effective new treatments for cancer over the next decade. These advances will arise from the identification and validation of new targets, the manipulation of tumour–host microenvironment interactions, and the optimization of antibody structure to promote the amplification of anti-tumour immune responses.

BOX 1. Interplay between T cell subsets in the tumour microenvironment.

Some solid tumours exhibit significant CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltrates. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are critical for anti-tumour immunity. They recognize specific peptides presented by tumour cells on MHC class I molecules and release perforin and granzymes to initiate tumour cell apoptosis. Tumour antigen-specific CTLs can be detected in the serum of cancer patients and the influx of antigen-specific CTLs in the tumour microenvironment is associated with favorable clinical outcomes100. CD4+ helper T (TH) cells can be subdivided into TH1, TH2, and TH17 cell subsets based on their cytokine expression profiles. TH1 cells promote the differentiation of naïve CD8+ T cells into activated CTLs by increasing the expression of stimulatory B7 family members on antigen presenting cells (APCs) as well as by producing IL-2, which stimulates T cell expansion. However, tumour-infiltrating CD4+ T cells are often TH2-polarized and secrete suppressive factors, such as IL-4 and IL-10, that can inhibit TH1 responses101. The roles of TH17 cells, which produce IL-17A, IL-22 and express IL-23R, in anti-tumour responses are currently being elucidated; reports show that TH17 cells can be involved in both the promotion of anti-tumour immunity102 and the enhancement of tumour growth103.

Regulatory T (TREG) cells derived from the thymus comprise another important subset of CD4+ T cells. They are defined by the coexpression of CD25 (IL-2Rα chain) and the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FOXP3), and function to suppress immune responses. Many solid tumours accumulate TREG cells in the tumour microenvironment and this accumulation is associated with poor clinical outcomes in some cancers45. TREG cells can exert their suppressive effects by (i) inducing expression of inhibitory B7 family members on APCs, (ii) directly killing APCs and effector T cells through perforin and granzyme release (iii) engagement of CD80 and CD86 on APC through CTLA4, which leads to T cell anergy and death and production of suppressive mediators such as IL-10 and TGFβ104. Therefore, effective anti-tumour immunity is critically dependent on optimizing the balance between tumour antigen-specific CTLs and immune-suppressive T cells in the tumour microenvironment.

Online Summary.

The past century has witnessed the evolution of the ‘magic bullet’ from concept to clinical reality. Therapeutic antibodies have been established as “standard of care” agents for several human cancers.

Therapeutic antibodies possess unique and multiple clinically relevant anti-tumour mechanisms: antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, complement-dependent cytotoxicity and the induction of T cell immunity through cross-presentation.

Antibodies directed against elements of the tumour microenvironment may synergize with antibodies targeting tumour antigens and provide enhanced therapeutic benefit.

FcγRs provide a key link between therapeutic antibodies and the cellular immune system and enable monoclonal antibodies to induce adaptive immune responses. Antibody-induced anti-tumour adaptive immunity against tumour-specific antigens might already contribute to the patterns of delayed and prolonged anti-tumour responses seen when antibodies are used alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

Monoclonal antibodies can exert synergistic anti-tumour effects in combination with other immunomodulatory approaches such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy agents, vaccines or other immunomodulators.

Advances in protein engineering have provided platforms for the development of novel antibody constructs (BiTE molecules) as well as engineered protein scaffolds (such as DARPins and Adnectins).

Acknowledgments

L.M.W. and S.W. are supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grants CA51008, CA50633, CA121033.)

Glossary terms

- monoclonal antibodies

Antibodies containing uniform variable regions and thus specific for a single epitope. Originally, monoclonal antibodies were derived from a single B lymphocyte clone. Genetic manipulation now allows genes from multiple sources of B lymphocytes (for example, mouse and human) to be combined

- chimeric antibody

An antibody encoded by genes from more than one species, usually with antigen-binding regions from mouse genes and constant regions from human genes. The aim of this process is to prevent an anti-mouse antibody response in humans treated with the antibody

- humanized antibody

A genetically engineered mouse antibody in which the protein sequence has been modified to increase the similarity of the antibody to human antibodies. This is to prevent an anti-mouse antibody response in humans treated with the antibody

- radioimmunoconjugates

These are antibodies that are conjugated to radionuclides and are designed to bind specifically to tumour antigens, so that only cancer cells are exposed to cytotoxic ionizing radiation

- HER2

Also known as ERBB2, is a type I membrane glycoprotein that is a member of the ERBB family of tyrosine kinase receptors. A tumour-associated antigen that is over-expressed in 10–40% of breast cancer and other carcinomas

- adjuvant chemotherapy

Chemotherapy given in addition to surgical therapy in order to reduce the risk of local or systemic relapse

- complement-dependent cytotoxicity

A mechanism of killing cells in which antibody bound to the target cell surface fixes complement, which results in assembly of the membrane attack complex that punches holes in the target cell membrane resulting in subsequent cell lysis

- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)

A sequence that is present in the cytoplasmic domains of the invariant chains of various cell-surface immune receptors. Following phosphorylation of their tyrosine residues, ITAMs function as docking sites for SRC homology 2 (SH2)-domain-containing tyrosine kinases and adaptor molecules, thereby facilitating intracellular-signalling cascades

- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM)

This motif is present in the cytoplasmic domain of several inhibitory receptors. After ligand binding, ITIMs are tyrosine phosphorylated and recruit inhibitory phosphatases

- antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)

A mechanism by which natural killer (NK) cells kill other cells, for example, virus-infected target cells that are coated with antibodies. The Fc portions of the coating antibodies interact with the Fc receptor that are expressed by NK cells, thereby initiating a signalling cascade that results in the release of cytotoxic granules (containing perforin and granzyme B), which induce apoptosis of the antibody-coated cell

- cross-presentation

The ability of certain antigen-presenting cells to load peptides that are derived from exogenous antigens onto MHC class I molecules and present these at the cell surface. This property is atypical, as most cells exclusively present peptides derived from endogenous proteins on MHC class I molecules

- angiogenesis

The process of developing new blood vessels. Angiogenesis is important in the normal development of the embryo and fetus. It is also important for tumour growth

- FOLFIRI

A chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of colorectal cancer, made up of the drug FOLinic Acid (Leucovorin), Fluorouracil (5-FU) and IRInotecan (Camptosar)

- heregulin

A family of ligands known to bind the HER3 and HER4 receptors, also capable of inducing phosphorylation of the HER2/neu receptor

- regulatory T cell

A type of CD4+ T cell that is characterized by its expression of forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) and high levels of CD25. TREG cells can downmodulate many types of immune responses

- disialoganglioside

A glycosphingolipid found in the brain and other nervous system tissues. Gangliosides are members of a group of galactose-containing cerebrosides with a basic composition of ceramide-glucose-galactose-N-acetyl neuraminic acid

- tumour-associated antigens

Antigens that are expressed by tumour cells. These belong to three main categories: tissue-differentiation antigens, which are also expressed by non-malignant cells; mutated or aberrantly expressed molecules; and cancer testis antigens, which are normally expressed only by spermatocytes and occasionally in the placenta

- co-stimulation

Receptor-mediated signals required in addition to antigen-receptor engagement to achieve complete lymphocyte activation

- bispecific antibody

Antibodies engineered to express two distinct antigen binding sites. Most often used therapeutically to physically cross-link a tumour cell and an immune effector cell

Biographies

Louis M. Weiner received his MD from Mount Sinai School of Medicine, trained in internal medicine at the University of Vermont and completed his hematology/oncology fellowship at Tufts-New England Medical Center. He was subsequently based at Fox Chase Cancer Center, where he served as Chairman of the Department of Medical Oncology and Vice President for Translational Research. He is currently the Director of the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center at Georgetown University Medical Center, and Chair of the Department of Oncology. Dr. Weiner’s research focuses on monoclonal antibody engineering and immunotherapy.

Rishi Surana is a M.D./Ph.D. student in the tumour biology training program at the Georgetown University Medical Center

Shangzi Wang received her Ph.D. from the Ocean University of China, Qingdao (China), and conducted her postdoctoral training with Dr. Weiner at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center at Georgetown University Medical Center.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Louis M. Weiner, Email: weinerl@georgetown.edu.

Rishi Surana, Email: rs382@georgetown.edu.

Shangzi Wang, Email: sw333@georgetown.edu.

References

- 1.Ehrlich P. Collected studies on immunity. New York: J. Wiley & Sons; 1906. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256:495–497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunkelberger JR, Song WC. Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res. 2010;20:34–50. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zipfel PF, Skerka C. Complement regulators and inhibitory proteins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nri2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors: old friends and new family members. Immunity. 2006;24:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.010. Comprehensive review of FcγR biology and the importance of FcγR interactions in modulating the immune response. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung YA, et al. Engineering human IgG1 affinity to human neonatal Fc receptor: impact of affinity improvement on pharmacokinetics in primates. J Immunol. 2009;182:7663–7671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiao SW, et al. Dependence of antibody-mediated presentation of antigen on FcRn. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9337–9342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams GP, Weiner LM. Monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1147–1157. doi: 10.1038/nbt1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunada H, Magun BE, Mendelsohn J, MacLeod CL. Monoclonal antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor is internalized without stimulating receptor phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3825–3829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim R. Cetuximab and panitumumab: are they interchangeable? Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1140–1141. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Cutsem E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuenen B, et al. A Phase I Pharmacologic Study of Necitumumab (IMC-11F8), a Fully Human IgG1 Monoclonal Antibody Directed Against EGFR in Patients with Advanced Solid Malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1915–1923. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li D, et al. Therapeutic anti-EGFR antibody 806 generates responses in murine de novo EGFR mutant-dependent lung carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:346–352. doi: 10.1172/JCI30446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gan HK, et al. Targeting a unique EGFR epitope with monoclonal antibody 806 activates NF-kappaB and initiates tumor vascular normalization. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:3993–4001. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott AM, et al. A phase I clinical trial with monoclonal antibody ch806 targeting transitional state and mutant epidermal growth factor receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4071–4076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611693104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen JS, Lan K, Hung MC. Strategies to target HER2/neu overexpression for cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updat. 2003;6:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s1368-7646(03)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogel CL, et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in first-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:719–726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudis CA. Trastuzumab--mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:39–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franklin MC, et al. Insights into ErbB signaling from the structure of the ErbB2-pertuzumab complex. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:317–328. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheuer W, et al. Strongly enhanced antitumor activity of trastuzumab and pertuzumab combination treatment on HER2-positive human xenograft tumor models. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9330–9336. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoeberl B, et al. Therapeutically targeting ErbB3: a key node in ligand-induced activation of the ErbB receptor-PI3K axis. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra31. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollmen M, Maatta JA, Bald L, Sliwkowski MX, Elenius K. Suppression of breast cancer cell growth by a monoclonal antibody targeting cleavable ErbB4 isoforms. Oncogene. 2009;28:1309–1319. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellis LM, Hicklin DJ. VEGF-targeted therapy: mechanisms of anti-tumour activity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krupitskaya Y, Wakelee HA. Ramucirumab, a fully human mAb to the transmembrane signaling tyrosine kinase VEGFR-2 for the potential treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:597–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackey J, et al. TRIO-012: a multicenter, multinational, randomized, double-blind phase III study of IMC-1121B plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel in previously untreated patients with HER2-negative, unresectable, locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9:258–261. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2009.n.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Y, et al. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 antagonist antibody as a therapeutic agent for cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6573–6584. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, D’Amore PA. PDGF, TGF-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:805–814. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen J, et al. Development of a fully human anti-PDGFRbeta antibody that suppresses growth of human tumor xenografts and enhances antitumor activity of an anti-VEGFR2 antibody. Neoplasia. 2009;11:594–604. doi: 10.1593/neo.09278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quezada SA, Jarvinen LZ, Lind EF, Noelle RJ. CD40/CD154 interactions at the interface of tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:307–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elgueta R, et al. Molecular mechanism and function of CD40/CD40L engagement in the immune system. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:152–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khalil M, Vonderheide RH. Anti-CD40 agonist antibodies: preclinical and clinical experience. Update Cancer Ther. 2007;2:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.uct.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oflazoglu E, et al. Macrophages and Fc-receptor interactions contribute to the antitumour activities of the anti-CD40 antibody SGN-40. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:113–117. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Advani R, et al. Phase I study of the humanized anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody dacetuzumab in refractory or recurrent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4371–4377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271:1734–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. First report that CTLA4 blockade can enhance anti-tumour immunity and promote tumour clearance. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shrikant P, Khoruts A, Mescher MF. CTLA-4 blockade reverses CD8+ T cell tolerance to tumor by a CD4+ T cell- and IL-2-dependent mechanism. Immunity. 1999;11:483–493. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peggs KS, Quezada SA, Chambers CA, Korman AJ, Allison JP. Blockade of CTLA-4 on both effector and regulatory T cell compartments contributes to the antitumor activity of anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1717–1725. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarnaik AA, Weber JS. Recent advances using anti-CTLA-4 for the treatment of melanoma. Cancer J. 2009;15:169–173. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181a7450f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Small EJ, et al. A pilot trial of CTLA-4 blockade with human anti-CTLA-4 in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1810–1815. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber J. Ipilimumab: controversies in its development, utility and autoimmune adverse events. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:823–830. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0653-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rabinovich GA, Gabrilovich D, Sotomayor EM. Immunosuppressive strategies that are mediated by tumor cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:267–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grutter C, et al. A cytokine-neutralizing antibody as a structural mimetic of 2 receptor interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20251–20256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807200106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrausch U, et al. Disruption of TGF-beta signaling prevents the generation of tumor-sensitized regulatory T cells and facilitates therapeutic antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183:3682–3689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curiel TJ, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Onizuka S, et al. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor alpha) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3128–3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hong H, et al. Depletion of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells enhances natural killer T cell-mediated anti-tumour immunity in a murine mammary breast cancer model. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;159:93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rech AJ, Vonderheide RH. Clinical use of anti-CD25 antibody daclizumab to enhance immune responses to tumor antigen vaccination by targeting regulatory T cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1174:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lazar GA, et al. Engineered antibody Fc variants with enhanced effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4005–4010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508123103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kubota T, et al. Engineered therapeutic antibodies with improved effector functions. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1566–1572. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000;6:443–446. doi: 10.1038/74704. Fc-receptor-dependent mechanisms contribute substantially to the antitumor effects of antibodies and indicate that an optimal antibody against tumors would bind preferentially to activating Fc receptors and minimally to the inhibitory FcγRIIB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cartron G, et al. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcgammaRIIIa gene. Blood. 2002;99:754–758. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.754. The first study to show that responsiveness to antibody therapy was associated with FcγRIII polymorphisms in patients. It strongly implicates the importance of Fc-FcγR dependent interactions, such as ADCC, in the antitumor activity of rituximab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weng WK, Levy R. Two immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms independently predict response to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3940–3947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Musolino A, et al. Immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with HER-2/neu-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1789–1796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bibeau F, et al. Impact of FcγRIIa-FcγRIIIa polymorphisms and KRAS mutations on the clinical outcome of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab plus irinotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1122–1129. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horton HM, et al. Potent in vitro and in vivo activity of an Fc-engineered anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody against lymphoma and leukemia. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8049–8057. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zalevsky J, et al. The impact of Fc engineering on an anti-CD19 antibody: increased Fcgamma receptor affinity enhances B-cell clearing in nonhuman primates. Blood. 2009;113:3735–3743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lundin J, et al. Phase II trial of subcutaneous anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) as first-line treatment for patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) Blood. 2002;100:768–773. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Di Gaetano N, et al. Complement activation determines the therapeutic activity of rituximab in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;171:1581–1587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cragg MS, Glennie MJ. Antibody specificity controls in vivo effector mechanisms of anti-CD20 reagents. Blood. 2004;103:2738–2743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Racila E, et al. A polymorphism in the complement component C1qA correlates with prolonged response following rituximab therapy of follicular lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6697–6703. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coiffier B, et al. Safety and efficacy of ofatumumab, a fully human monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a phase 1–2 study. Blood. 2008;111:1094–1100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang SY, et al. Depletion of the C3 component of complement enhances the ability of rituximab-coated target cells to activate human NK cells and improves the efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapy in an in vivo model. Blood. 2009;4:5322–5330. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-200469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cartron G, Watier H, Golay J, Solal-Celigny P. From the bench to the bedside: ways to improve rituximab efficacy. Blood. 2004;104:2635–2642. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Albert ML, Sauter B, Bhardwaj N. Dendritic cells acquire antigen from apoptotic cells and induce class I-restricted CTLs. Nature. 1998;392:86–89. doi: 10.1038/32183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berard F, et al. Cross-priming of naive CD8 T cells against melanoma antigens using dendritic cells loaded with killed allogeneic melanoma cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1535–1544. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hoffmann TK, Meidenbauer N, Dworacki G, Kanaya H, Whiteside TL. Generation of tumor-specific T-lymphocytes by cross-priming with human dendritic cells ingesting apoptotic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3542–3549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dhodapkar KM, Krasovsky J, Williamson B, Dhodapkar MV. Antitumor monoclonal antibodies enhance cross-presentation of cellular antigens and the generation of myeloma-specific killer T cells by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:125–133. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011097. Important study describing cross-presentation as one potential mechanism of action of anti-cancer monoclonal antibodies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dhodapkar KM, et al. Selective blockade of inhibitory Fcgamma receptor enables human dendritic cell maturation with IL-12p70 production and immunity to antibody-coated tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2910–2915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500014102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haynes NM, van der Most RG, Lake RA, Smyth MJ. Immunogenic anti-cancer chemotherapy as an emerging concept. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:545–557. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hurwitz H, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. Important clinical trial leading to the approval of bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Slamon DJ, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. Phase III clinical trial important for the approval of trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy as a treatment for HER2 overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taylor C, et al. Augmented HER-2 specific immunity during treatment with trastuzumab and chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5133–5143. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Coiffier B, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Forstpointner R, et al. The addition of rituximab to a combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone (FCM) significantly increases the response rate and prolongs survival as compared with FCM alone in patients with relapsed and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2004;104:3064–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McBride WH, et al. A sense of danger from radiation. Radiat Res. 2004;162:1–19. doi: 10.1667/rr3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bonner JA, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol. 2009;11:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Willett CG, et al. Efficacy, safety, and biomarkers of neoadjuvant bevacizumab, radiation therapy, and fluorouracil in rectal cancer: a multidisciplinary phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3020–3026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gulley JL, et al. Combining a recombinant cancer vaccine with standard definitive radiotherapy in patients with localized prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3353–3362. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roses RE, Xu M, Koski GK, Czerniecki BJ. Radiation therapy and Toll-like receptor signaling: implications for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:200–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khan KD, et al. A phase 2 study of rituximab in combination with recombinant interleukin-2 for rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7046–7053. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alpaugh RK, et al. Phase IB trial for malignant melanoma using R24 monoclonal antibody, interleukin-2/alpha-interferon. Med Oncol. 1998;15:191–198. doi: 10.1007/BF02821938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van der Kolk LE, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Baars JW, van Oers MH. Treatment of relapsed B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with a combination of chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (rituximab) and G-CSF: final report on safety and efficacy. Leukemia. 2003;17:1658–1664. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gilman AL, et al. Phase I study of ch14.18 with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-2 in children with neuroblastoma after autologous bone marrow transplantation or stem-cell rescue: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:85–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huang X, et al. Combined therapy of local and metastatic 4T1 breast tumor in mice using SU6668, an inhibitor of angiogenic receptor tyrosine kinases, and the immunostimulator B7.2-IgG fusion protein. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5727–5735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Matar P, et al. Combined epidermal growth factor receptor targeting with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (ZD1839) and the monoclonal antibody cetuximab (IMC-C225): superiority over single-agent receptor targeting. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6487–6501. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ramalingam S, et al. Dual inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor with cetuximab, an IgG1 monoclonal antibody, and gefitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with refractory non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a phase I study. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:258–264. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181653d1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Scaltriti M, et al. Lapatinib, a HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, induces stabilization and accumulation of HER2 and potentiates trastuzumab-dependent cell cytotoxicity. Oncogene. 2009;28:803–814. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Blackwell KL, et al. Randomized study of Lapatinib alone or in combination with trastuzumab in women with ErbB2-positive, trastuzumab-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1124–1130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.van Elsas A, Hurwitz AA, Allison JP. Combination immunotherapy of B16 melanoma using anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing vaccines induces rejection of subcutaneous and metastatic tumors accompanied by autoimmune depigmentation. J Exp Med. 1999;190:355–366. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Takaku S, et al. Blockade of TGF-beta enhances tumor vaccine efficacy mediated by CD8(+) T cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;126:1666–1674. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Terabe M, et al. Synergistic enhancement of CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor vaccine efficacy by an anti-transforming growth factor-beta monoclonal antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6560–6569. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Disis ML, et al. Concurrent trastuzumab and HER2/neu-specific vaccination in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4685–4692. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wolf E, Hofmeister R, Kufer P, Schlereth B, Baeuerle PA. BiTEs: bispecific antibody constructs with unique anti-tumor activity. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1237–1244. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brischwein K, et al. MT110: a novel bispecific single-chain antibody construct with high efficacy in eradicating established tumors. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:1129–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gebauer M, Skerra A. Engineered protein scaffolds as next-generation antibody therapeutics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.04.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mamluk R, et al. Anti-tumor effect of CT-322 as an adnectin inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. MAbs. 2010;2:199–208. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.2.11304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jahrsdorfer B, Weiner GJ. Immunostimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and antibody therapy of cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:476–482. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(03)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Metelitsa LS, et al. Antidisialoganglioside/granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor fusion protein facilitates neutrophil antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and depends on FcgammaRII (CD32) and Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) for enhanced effector cell adhesion and azurophil granule exocytosis. Blood. 2002;99:4166–4173. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pages F, et al. Immune infiltration in human tumors: a prognostic factor that should not be ignored. Oncogene. 2009;29:1093–1102. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tassi E, et al. Non-redundant role for IL-12 and IL-27 in modulating Th2 polarization of carcinoembryonic antigen specific CD4 T cells from pancreatic cancer patients. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Martin-Orozco N, et al. T helper 17 cells promote cytotoxic T cell activation in tumor immunity. Immunity. 2009;31:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Langowski JL, et al. IL-23 promotes tumour incidence and growth. Nature. 2006;442:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nature04808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]