Abstract

Light-dependent inorganic C (Ci) transport and accumulation in air-grown cells of Synechococcus UTEX 625 were examined with a mass spectrometer in the presence of inhibitors or artificial electron acceptors of photosynthesis in an attempt to drive CO2 or HCO3− uptake separately by the cyclic or linear electron transport chains. In the presence of 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea, the cells were able to accumulate an intracellular Ci pool of 20 mm, even though CO2 fixation was completely inhibited, indicating that cyclic electron flow was involved in the Ci-concentrating mechanism. When 200 μm N,N-dimethyl-p-nitrosoaniline was used to drain electrons from ferredoxin, a similar Ci accumulation was observed, suggesting that linear electron flow could support the transport of Ci. When carbonic anhydrase was not present, initial CO2 uptake was greatly reduced and the extracellular [CO2] eventually increased to a level higher than equilibrium, strongly suggesting that CO2 transport was inhibited and that Ci accumulation was the result of active HCO3− transport. With 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea-treated cells, Ci transport and accumulation were inhibited by inhibitors of CO2 transport, such as COS and Na2S, whereas Li+, an HCO3−-transport inhibitor, had little effect. In the presence of N,N-dimethyl-p-nitrosoaniline, Ci transport and accumulation were not inhibited by COS and Na2S but were inhibited by Li+. These results suggest that CO2 transport is supported by cyclic electron transport and that HCO3− transport is supported by linear electron transport.

Cyanobacteria grown under limited C conditions develop a mechanism for the active transport of Ci, which can lead to intracellular Ci concentrations in excess of 1000 times the extracellular Ci concentration (Kaplan et al., 1980; Shelp and Canvin, 1984; Espie and Canvin, 1987; Espie et al., 1988a; Miller et al., 1990; Badger and Price, 1992). CO2 and HCO3− are transported by separate and independent systems (Espie et al., 1988a, 1988b; Miller et al., 1988b; Price et al., 1992; Salon et al., 1996a).

Light supplies the energy for active Ci transport, because no transport occurs in the dark (Shelp and Canvin, 1984; Ogawa et al., 1985b; Kaplan et al., 1987; Sültemeyer et al., 1993). Action spectrum studies suggest that PSI is primarily responsible for the supply of energy for transport, but a low level of PSII activity is apparently required for activation of Ci uptake (Ogawa et al., 1985a; Kaplan et al., 1987).

Somewhat puzzling was the observation that DCMU completely inhibited Ci fixation but did not completely inhibit Ci transport and the formation of the intracellular Ci pool (Ogawa et al., 1985a; Kaplan et al., 1987; Miller et al., 1988c; Ritchie et al., 1996). CO2 transport but not HCO3− transport was inhibited in a mutant with a defect in cyclic electron flow (Ogawa, 1993). We have also observed significant Ci transport and accumulation when PSI electron acceptors such as PNDA and methyl viologen are supplied (Li and Canvin, 1997b), suggesting that some transport can be supported by linear electron transport.

To investigate the photosynthetic reactions that may be involved in providing energy for CO2 and HCO3− transport and accumulation, we examined Ci uptake in the presence of inhibitors and artificial electron acceptors of photosynthesis. Our results suggest that CO2 transport is supported by cyclic electron transport and HCO3− transport is supported by linear electron transport.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and Growth

The unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus leopoliensis UTEX 625 (University of Texas Culture Collection, Austin) was grown at 30°C in modified, unbuffered Allen's medium bubbled with air, as previously described (Espie and Canvin, 1987; Li and Canvin, 1997a). Cells were harvested 48 h after inoculation. At that time, the Chl a concentration was between 4 and 5 μg Chl mL−1, the [Ci] was 50 μm, and the pH of the medium was 9.6.

Experimental Procedure

Prior to experiments, cells were washed three times in 25 mm BTP-HCl, pH 8.0, as previously described (Li and Canvin, 1997a). The resuspended cells were transferred into a glass chamber (40 mm in diameter) at 30°C and 80 μmol m−2 s−1 light and allowed to fix contaminant Ci in the buffer and reach the CO2 compensation point (Miller and Canvin, 1989). The chamber was flushed with CO2-free air to facilitate the removal of the Ci. The Chl content was determined spectrophotometrically at 665 nm after extraction in methanol (MacKinney, 1941).

All measurements were performed by MS. When required, 6 mL of cell suspension was transferred to the reaction chamber (20 mm in diameter) connected via a membrane inlet to the mass spectrometer and allowed to reach the CO2 compensation point at 30°C and pH 8.0. White light to drive Ci transport and photosynthesis was provided by a tungsten halogen projection lamp at 400 μmol m−2 s−1. The [O2] during the experiments was maintained between 80 and 100 μm.

MS

A membrane inlet mass spectrometer (model MM 14–80 SC, VG Gas Analysis Systems, Middlewich, UK) was used in these experiments. Concentrations of 16O2, 12CO2, and 13CO2 (m/z 32, 44, and 45, respectively), in the 6-mL reaction chamber were measured simultaneously. The output signal was directed to a computer (486, Altair, Kingston, Canada), and the mass spectrometer was controlled using software (Spectrascan 5.3.1, Petrasoft 5.3.2) from the same company as the spectrometer (VG Gas Analysis Systems). The suspension was stirred with a rotating magnetic bar. Gases and chemicals were introduced into the reaction chamber through a small port. A response time of 2.3 s was obtained with two masses, and 1.1 s was obtained with one mass.

Calibration for CO2 was performed by injecting known amounts of K213CO3 into the stoppered cuvette in 6 mL of BTP-HCl, pH 8.0, and calculation of the equilibrium concentration of CO2 at 30°C and pH 8.0 was as described by Miller et al. (1988a). Calibration for 16O2 was made as described previously (Miller et al., 1988a; Li and Canvin, 1997a). The value of 16O2 concentration in equilibrium with air was taken as 240 μm. Rates of 16O2 evolution were calculated from the slope of the 32 signal after the appropriate corrections were made for leak rates (2% h−1) during the course of the experiment (Miller et al., 1988a).

Ci Uptake and Accumulation

The activity of CO2 uptake and the intracellular Ci pool size were measured using the mass spectrometer by following the [CO2] after the addition of 13Ci to the medium both in the presence and in the absence of CA. In the absence of added CA, the intracellular Ci pool was determined either by taking a sample or by injecting CA into the medium (Salon et al., 1996a). When CA is present the [CO2] represents total Ci (Badger and Price, 1994). In the presence of IAC, the Ci transported into the cells was not fixed and leaked back into the medium when the light was turned off. The intracellular Ci was determined as the difference between the external [Ci] in the light and the [Ci] that occurred at equilibrium upon darkening the cells. Similar estimates were made when CO2 fixation was allowed. The internal [Ci] was calculated using an intracellular volume of 75 μL mg−1 Chl (Miller et al., 1988c).

Chemicals

PNDA, Na2S, IAC, CA, and BTP were obtained from Sigma. K213CO3 (99 atom % 13C) was obtained from MSD Isotopes (Montreal, Canada). The K213CO3 was dissolved in BTP-HCl, pH 8.0, as a concentrated solution for addition to the reaction medium (Miller et al., 1988b). PNDA was dissolved in DMSO, and DCMU was dissolved in methanol before use. COS was obtained in lecture bottles from Matheson Gas Products (Ontario, Canada). Solutions of COS were prepared as described previously (Miller et al., 1989; Salon et al., 1996b).

RESULTS

Ci Uptake and Accumulation and Effect of DCMU and PNDA

For air-grown cells of Synechococcus UTEX 625 we showed previously that light-dependent Ci uptake and accumulation can be determined using a mass spectrometer equipped with a membrane inlet system that measures the extracellular concentration of dissolved CO2 (Miller et al., 1988c; Espie et al., 1989; Salon et al., 1996b). Figure 1, A and F, shows the time course of CO2 depletion following illumination of the suspensions after they had been incubated in the dark with 100 μm Ci in the presence of the CO2-fixation inhibitor IAC. When measurements were made with added CA in the reaction mixture (Fig. 1A), the CO2 signal was directly proportional to the total [Ci]. The disappearance of CO2 from the medium represented transport and accumulation of total Ci within the cells.

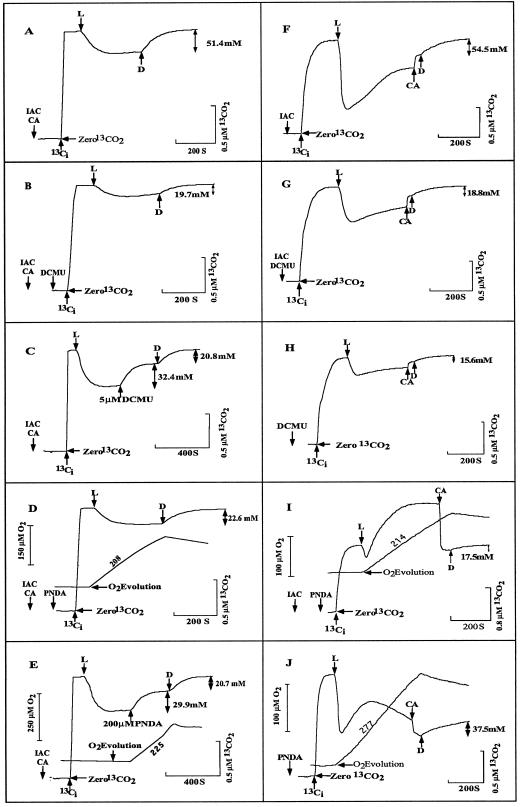

Figure 1.

The effect of 5 μm DCMU (B, C, G, and H) and 200 μm PNDA (D, E, I, and J) on changes in the [CO2] (A and F) of the medium in air-grown cells of Synechococcus UTEX 625. Cells were preincubated in 25 mm BTP-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, in the light in the presence of 25 mm NaCl and 25 μg mL−1 CA (A–E) or 25 mm NaCl (F–J). After reaching the CO2-compensation point, the cells were darkened and IAC (3.3 mm) was added 5 min before Ci injection (A–G and I). DCMU or PNDA was injected either 10 s before the addition of Ci (B, D, and G–J) or during Ci uptake, as indicated (C and E). Ci was added to yield a final [Ci] of 100 μm, as indicated (↑). Ci uptake was initiated by turning on the light (L), and cells were darkened (D↑) to allow intracellular Ci to leak back into the medium. The size of the intracellular Ci pool (↕) is shown. When CA was not present initially, it was added before darkening (F–J). In D, E, I, and J, simultaneous measurements of O2 evolution were made, and numbers by the O2 traces represent the rates of O2 evolution in micromoles per milligram of Chl per hour. The addition of CA, even in the absence of cells, caused a 10% increase in the CO2 signal, and this enhancement has been subtracted from the actual tracing record (F–J). [Chl] (in micrograms per milliliter) was 6.3 in A; 6.5 in B; 9.2 in C, D, and E; 4.57 in F and G; 7.2 in H; 5.2 in I; and 5.75 in J. Chemicals other than NaCl added before the Ci are shown in the figures without regard to time of addition.

Upon darkening, the intracellular Ci that had been accumulated into the cells by the Ci-concentrating mechanism leaked out, as shown by the increase in the extracellular CO2 trace (Fig. 1A). When the light was switched on in the absence of CA, there was a rapid decline in [CO2], followed by a gradual increase to a steady-state level (Fig. 1F). After a period of CO2 uptake, the addition of CA in the light resulted in an increase in the [CO2] in the medium (Fig. 1F), indicating a disequilibrium of the HCO3−-CO2 system prior to the addition of CA. The Ci taken up by the cells was quantitatively released back into the medium when the actinic light was turned off (Fig. 1F).

The effect of DCMU (5 μm) on the ability of cells to take up and accumulate Ci is shown in Figure 1 (B, C, G, and H). The experiments were carried out in the presence of 25 mm Na+ and in the presence (Fig. 1, B and C) or absence (Fig. 1, G and H) of added CA in cells in which CO2 fixation was either inhibited with IAC (Fig. 1, B, C, and G) or not inhibited (Fig. 1H). In the presence of added DCMU, upon illumination there was substantial disappearance of CO2 from the medium (Fig. 1B). Since the cells were incubated with added CA to maintain the CO2-HCO3− equilibrium, the disappearance of CO2 from the medium represented transport and accumulation of total Ci. The CO2 taken up by the cells was quantitatively released back into the medium when the actinic light was turned off, and an intracellular Ci pool of 19.7 mm was observed (Fig. 1B). A similar intracellular Ci pool remained when DCMU was added to the cells during Ci uptake (Fig. 1C).

In the absence of CA, a rapid uptake of CO2 occurred and the extracellular [CO2] was maintained below the initial level whether CO2 fixation was inhibited (Fig. 1G) or not inhibited (Fig. 1H; compare with Fig. 1F). The CO2 and HCO3− were not in equilibrium, because after a steady extracellular CO2 level was observed, the addition of CA caused an increase in [CO2]. When the lights were turned off, the [CO2] returned to the initial level. The calculated Ci pool sizes were 18.8 mm (Fig. 1G) for IAC-inhibited cells and 15.6 mm (Fig. 1H) for noninhibited cells. In the latter case, the addition of DCMU prevented any CO2 fixation.

The changes in extracellular [CO2] with 200 μm PNDA were also monitored in cells in which CO2 fixation was inhibited with IAC (Fig. 1, D, E, and I) or not inhibited (Fig. 1J). O2 evolution was also recorded. With added CA, [CO2] and hence [Ci] decreased upon illumination. The Ci transported into the cells was not fixed and leaked back into the medium when the lights were turned off (Fig. 1, D and E). The calculated intracellular Ci pool size was 22.6 mm (Fig. 1D) when PNDA was added at the beginning of the experiment and 20.7 mm when the same concentration of PNDA was added during Ci uptake (Fig. 1E).

When the experiments with PNDA were performed in the absence of CA, different results were observed (Fig. 1, I and J). After the equilibrium of CO2 and HCO3− was established and the light was turned on, the [CO2] initially decreased. After a short time, however, the [CO2] in the medium increased whether CO2 fixation was inhibited with IAC (Fig. 1I) or not inhibited (Fig. 1J). When CO2 fixation was inhibited, the [CO2] increased to a constant level that was much higher than the initial equilibrium concentration. The addition of CA resulted in a decrease in the [CO2], showing that the [CO2] had been above the equilibrium value. The extracellular [CO2] strongly suggests that Ci accumulation was the result of active HCO3− transport and that CO2 transport was inhibited (Badger, 1985; Salon et al., 1996b, 1997). When the cells were darkened, the intracellular Ci pool appeared in the medium and the extracellular [CO2] returned to its initial equilibrium value (Fig. 1I). The intracellular Ci pool was 17.5 mm (Fig. 1I).

When CO2 fixation was not inhibited with IAC (Fig. 1J), PNDA caused similar changes in the extracellular [CO2], but the [CO2] never increased above the initial value. Again, the addition of CA showed that the [CO2] was above the equilibrium value. In this case a much larger intracellular Ci pool (37.5 mm) was observed.

When CO2 fixation was inhibited (Fig. 1, D, E, and I), PNDA supported substantial rates of O2 evolution. When CO2 fixation was allowed (Fig. 1J), the rate of O2 evolution was higher, possibly reflecting both CO2 and PNDA reduction. As shown by the initial and final [CO2] about one-half of the Ci was fixed during the experiment. PNDA does not completely inhibit CO2 fixation (Li and Canvin, 1997b).

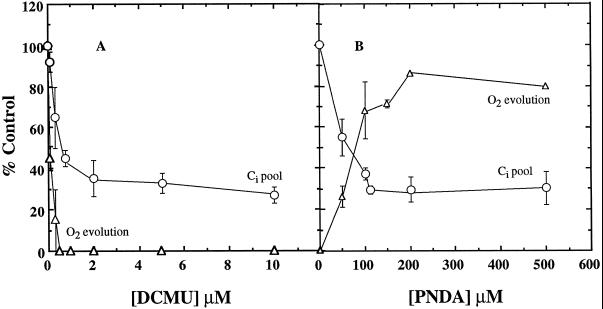

The effect of [DCMU] or [PNDA] is shown in Figure 2. At 0.5 μm DCMU, O2 evolution was completely inhibited but Ci accumulation was still more than 45% of that obtained in control cells (Fig. 2A). Even at 10 μm DCMU, Ci accumulation was 28% of the control. Significant Ci accumulation occurred even upon addition of 500 μm PNDA, and O2 evolution as high as 240 μmol mg−1 Chl h−1 was observed (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Effect of [DCMU] (A) and [PNDA] (B) on the rate of O2 evolution (▵) and the intracellular Ci pool (○). Cells (6–9 μg Chl mL−1) were incubated in the presence of 25 mm NaCl and 25 μg mL−1 CA and allowed to reach the CO2-compensation point. IAC (3.3 mm) was added; 5 min later the cells were darkened and 100 μm Ci was injected. After about 1 min, Ci transport and accumulation were initiated by turning on the light. DCMU or PNDA was added to the cells after the internal Ci pool had reached its maximum size. The Ci pool remaining after DCMU and PNDA addition was calculated upon darkening the cells. The control rate of O2 evolution was 256 μmol mg−1 Chl h−1. The maximum size of the internal pool was 56 mm. The data are given as means ± sd (n = 2–5).

Cyclic Electron Flow-Dependent Active CO2 Transport and Linear Electron Flow-Dependent HCO3− Transport

It has been well established that active transport of CO2 and HCO3− proceeds via separate and independent transporters (Espie et al., 1989; Miller and Canvin, 1989; Salon et al., 1996a). CO2 transport is inhibited by COS or Na2S (Espie et al., 1988b, 1989; Miller et al., 1989), and HCO3− transport is inhibited by Li+ in air-grown cells of Synechococcus UTEX 625 (Espie et al., 1988b; Miller et al., 1988b, 1990; Espie and Kandasamy, 1994). Therefore, it was of interest to determine the effects of these inhibitors on Ci uptake and accumulation in DCMU- and PNDA-treated cells.

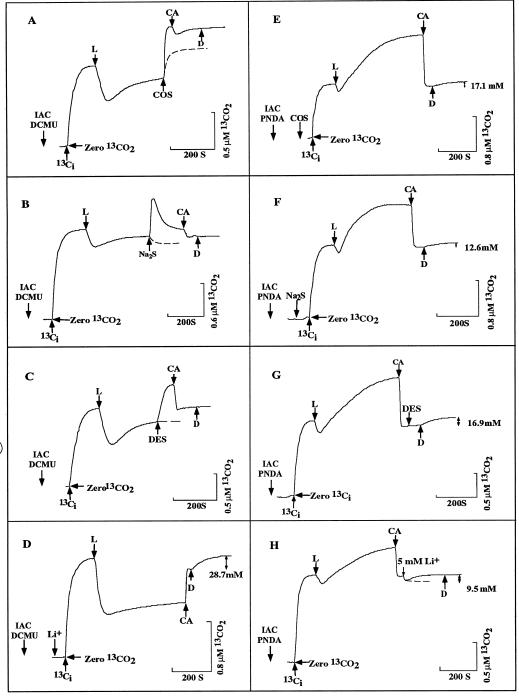

When 30 μm COS (Fig. 3A) or 200 μm Na2S (Fig. 3B) was added to cell suspensions that had been allowed to concentrate Ci internally in the presence of 5 μm DCMU, there was an immediate increase in the [CO2]. It has been well documented that there is always a burst of CO2 in the light when CO2 transport is quenched by various compounds (Miller et al., 1989; Salon et al., 1996b). The effects of COS and Na2S were rapid, and we interpret the fast increase in the extracellular [CO2] as being due to rapid leakage of the CO2 that had been accumulated within cells. Darkening the cells after CA equilibration did not result in any increase in the [CO2], indicating that the previously accumulated Ci pool had leaked from cells upon injection of COS or Na2S (Fig. 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

Effects of COS (30 μm, A and E), Na2S (200 μm, B and F), DES (10 μm, C and G), and Li+ (D and H) on Ci uptake in the presence of DCMU (A–D) or PNDA (E–H). Cell suspensions were incubated in the presence of 25 mm (A–G) or 5 mm NaCl (H) and allowed to reach the CO2-compensation point. IAC (3.3 mm) was added, and 5 min later cells were darkened and either 5 μm DCMU (A-D) or 200 μm PNDA (E–H) and 100 μm Ci was injected in the dark. After Ci equilibration, the light was switched on as indicated (L) and Ci was allowed to accumulate. The inhibitors were injected either during Ci uptake, as indicated (A–C, G, and H) or before the addition of Ci (D, E, and F). The effect of the inhibitors was rapid, and there were no difference in terms of order of addition. After CA addition the cells were darkened and the size of the intracellular Ci pool (↕) was determined. Results were corrected for changes due to CA addition. The dashed lines indicate the changes in m/z = 45 signal seen upon the addition of the inhibitor in the absence of cells. [Chl] (in micrograms per milliliter) was 10.4 in A and C; 4.57 in B; 5 in D and G; 9 in H; and 5.75 in E and F. Chemicals other than NaCl added before the Ci are shown in the figures without regard to time of addition.

The effect of COS and Na2S on Ci uptake and accumulation with PNDA-treated cells was also determined (Fig. 3, E and F). The inhibitors were incubated with cells in the dark and then 100 μm Ci was injected. The formation of significant intracellular Ci pools occurred in the presence of added 30 μm COS (Fig. 3E) or 200 μm Na2S (Fig. 3F) in the light. The pattern of Ci uptake and accumulation was typical of that seen when HCO3− transport occurs in the absence of CO2 transport (Salon et al., 1996b). The results, therefore, indicated that CO2 inhibitors had little effect on Ci transport and accumulation in PNDA-treated cells.

When cells were allowed to accumulate Ci internally in the presence of 5 μm DCMU, the addition of DES (Fig. 3C), an inhibitor of membrane-bound ATPase (McEnery and Pederson, 1986), resulted in a rapid increase in the extracellular [CO2] to above the initial equilibrium level. The addition of CA to cells in the light caused a decrease in [CO2] and a rapid re-establishment of the CO2-HCO3− equilibrium. As shown by the absence of an increase in the extracellular [CO2] upon darkening, all or most of the intracellular Ci had leaked from the cells upon the addition of DES (Fig. 3C). When the same concentration of DES was added to PNDA-treated cells, there was no burst of CO2 and the cells still retained an intracellular pool of 16.9 mm (Fig. 3G).

When 5 mm Li+ was added to a cell suspension that had been allowed to concentrate Ci internally in the presence of 200 μm PNDA and 5 mm Na+ (Fig. 3H), there was a slow increase in [CO2]. Upon darkening, there was no further increase in the [CO2], indicating that the accumulated Ci had leaked out upon the addition of Li+. The degree of Li+ inhibition on Ci accumulation was largely reversed by increasing the [Na+]. In the presence of 25 mm Na+, 5 mm Li+ inhibited Ci accumulation by only 15%, whereas 50 mm Li+ reduced the accumulation by 70% (data not shown). For cells treated with DCMU, however, the uptake of CO2 proceeded normally in the presence of 50 mm Li+ and cells were able to accumulate an intracellular Ci pool of 28.7 mm (Fig. 3D).

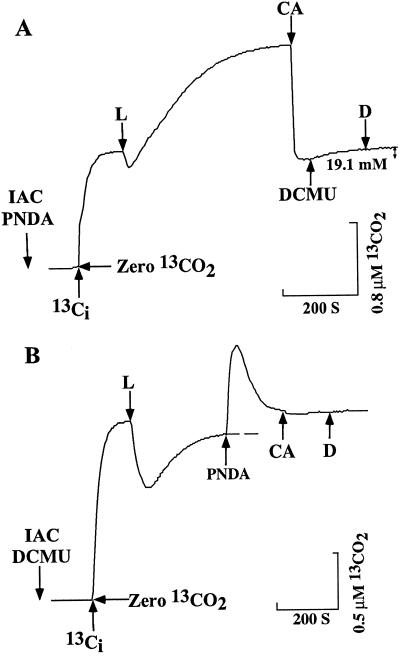

The addition of 1 μm DCMU results in the discharge of the PNDA-supported intracellular Ci pool (Fig. 4A), and PNDA addition results in the discharge of the intracellular Ci pool in the presence of DCMU.

Figure 4.

The effects of 1 μm DCMU (A) on Ci uptake and accumulation with PNDA and 100 μm PNDA (B) on Ci uptake and accumulation with DCMU in the absence of CA. Cell suspensions containing 25 mm NaCl with 100 μm Ci and 3.3 mm IAC were incubated as described in Figure 1, with 5 μm DCMU (B) or 200 μm PNDA (A). After Ci equilibration, the light was switched on as indicated (L) and Ci was allowed to accumulate. DCMU and PNDA were injected as indicated, and CA was added either before the addition of DCMU (A) or after the addition of PNDA (B) to maintain the CO2-HCO3− equilibrium. The light was turned off as indicated (D). [Chl] was 5.75 (A) and 3.9 μg mL−1 (B).

DISCUSSION

The use of MS to monitor the free [CO2] in the medium provides a direct measurement of the extent of Ci uptake and accumulation (Badger, 1985; Miller et al., 1988c; Salon et al., 1996a, 1996b). It has also allowed active CO2 transport to be distinguished from HCO3− transport in air-grown cyanobacteria (Espie et al., 1988a, 1989; Salon et al., 1996a, 1996b), in which only Na+-dependent HCO3− transport occurs. In the present study the MS technique was used to determine the capacities to which Ci uptake could occur in the presence of inhibitors or artificial electron acceptors of photosynthesis to identify the role of photosynthetic electron transport in the operation of the Ci-concentrating mechanism.

It is well established that cells of cyanobacteria, when grown at air levels of CO2, have developed the capacity to accumulate high intracellular [Ci]. The accumulation of Ci is an active transport process, since it occurs only in the light and against concentration and electrochemical gradients (Fig. 1, A and F; Badger et al., 1980; Shelp and Canvin, 1984; Miller et al., 1990). Photosynthesis supplies energy for the concentrating mechanism (Badger et al., 1980; Ogawa et al., 1985b; Kaplan et al., 1987), although the reactions involved in providing the energy for this process are not known. It has been suggested that PSI-driven cyclic electron flow is the source of energy (Ogawa and Inoue, 1983; Ogawa et al., 1985a, 1985b; Ogawa, 1993). However, the fact that DCMU inhibits the accumulation of Ci and the enhanced Mehler reaction in low-CO2 cells suggests the involvement of linear electron transport (pseudocyclic photophosphorylation) in the operation of the Ci-concentrating mechanism (Miller et al., 1988a, 1991; Sültemeyer et al., 1993).

Data presented in Figure 1 clearly demonstrate that the ability to concentrate Ci is reduced by the presence of higher concentrations of DCMU and PNDA, but the cells still retained some concentrating capacity. It can be seen that the intracellular [Ci] was 34.5% of that in the absence of DCMU (Fig. 1, F and G) and 32.1% of that in the absence of PNDA (Fig. 1, F and I). The intracellular Ci accumulation occurred only in the light, suggesting that cyclic or linear electron flow can at least partially drive Ci uptake. PNDA accepts electrons from PSI (Elstner and Zeller, 1978), and the high rate of O2 evolution that was observed even in the presence of IAC indicates that it is an efficient acceptor of PSI-derived electrons (Fig. 1, D, E, I, and J). The rate of O2 evolution was higher in noninhibited than in inhibited cells. Significant Ci accumulation occurred even upon the addition of a high concentration of PNDA. These observations are consistent with the results obtained by Li and Canvin (1997b).

A similar concentrating capacity was observed when cells were treated with methyl viologen, which also accepts electrons from PSI (data not shown). However, when the electrons were drained to the PSII acceptors 2,6-dimethylbenzoquinone or oxidized diaminodurene, no intracellular Ci accumulation was observed (data not shown). The inhibition of the intracellular Ci accumulation in PNDA-treated cells by 1 μm DCMU is also supportive of the concept that the electron transport from water to Fd (PNDA) is involved in the transport of Ci (Fig. 4A). Evidently, the transport of Ci is driven only by PSI in DCMU-treated cells. In this case, 100 μm PNDA totally suppressed the ability of cells to accumulate Ci internally (Fig. 4B).

In the absence of added CA, much larger differences between DCMU- and PNDA-treated cells were observed in the extracellular [CO2] traces. When cells were incubated with DCMU, the [CO2] in the medium was rapidly reduced and maintained this low level during the light. Darkening the cells resulted in only a transient excess of the expected equilibrium level whether or not CO2 fixation was allowed (Fig. 1, G and H). In contrast, when cells were incubated with PNDA, a rapid uptake of CO2 was initially observed, but then the extracellular [CO2] increased much higher than the expected equilibrium value (Fig. 1, I and J). The addition of CA restored the extracellular HCO3−-CO2 equilibrium, and when the cells were darkened the intracellular Ci pool appeared in the medium (Fig. 1, I and J).

Salon et al. (1996b) also observed this CO2 release in cells treated with CO2 transport inhibitors. In this case, cells continued to transport HCO3−, which was converted to CO2, which leaked from the cells because it could not be retransported. The differences in the patterns between DCMU- and PNDA-treated cells in the absence of added CA can be explained. In the presence of PNDA, active HCO3− transport was responsible for the accumulation of the intracellular Ci pool and the increase in the extracellular [CO2] was due to rapid leakage of CO2 from cells. The observation that Ci uptake and accumulation in DCMU-treated cells were inhibited by CO2-transport inhibitors such as COS and Na2S, whereas the HCO3−-transport inhibitor Li+ inhibited Ci accumulation in PNDA-treated cells supports this interpretation (Fig. 3, A, B, E, and F).

As discussed earlier, the accumulation of Ci proceeds against a concentration gradient, which implies that it must be an energy-requiring process. In an earlier work, DES inhibited the transport of CO2 (Miller et al., 1988c). In the present study, 10 μm DES completely inhibited CO2 accumulation in DCMU-treated cells, indicating that CO2 transport was fueled by ATP (Fig. 3C). HCO3− transport and accumulation, however, could proceed in the presence of the same concentration of DES in PNDA-treated cells (Fig. 3H). These results suggest that PNDA-dependent linear electron flow was responsible for the Ci accumulation, and the linear electron flow may be more important than its coupling to ATP formation. We do not know how linear electron transport supplies the energy for HCO3− transport or why CO2 transport appears to be driven only by ATP generated through cyclic phosphorylation (Ogawa, 1993). Linear electron transport should also generate ATP, but it does not appear to be available to drive CO2 transport. If it drives HCO3− transport, the ATPase involved would not be sensitive to DES. Further speculation on energy coupling is possible, but any firm conclusions concerning the subject cannot be made at the present time.

Abbreviations:

- BTP

1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino] propane

- CA

carbonic anhydrase (carbonate dehydratase, EC 4.2.1.1)

- Chl

chlorophyll

- Ci

dissolved inorganic carbon (CO2 + HCO3− + CO32−)

- DES

diethylstilbestrol

- IAC

iodoacetamide

- PNDA

N,N-dimethyl-p-nitrosoaniline

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

LITERATURE CITED

- Badger MR (1985) The fluxes of inorganic carbon species during photosynthesis in cyanobacteria with particular reference to Synechococcus sp. In WJ Lucas, JA Berry, eds, Inorganic Carbon Uptake by Aquatic Photosynthetic Organisms. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 39–52

- Badger MR, Kaplan A, Berry JA. Internal inorganic carbon pool of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Evidence for a carbon dioxide concentrating mechanism. Plant Physiol. 1980;66:407–413. doi: 10.1104/pp.66.3.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. The CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria and green algae. Physiol Plant. 1992;84:606–615. [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. The role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1994;45:369–392. [Google Scholar]

- Elstner EF, Zeller H. Bleaching of p-nitrosodimethylaniline by photosystem I of chloroplast lamellae. Plant Sci Lett. 1978;13:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Espie GS, Canvin DT. Evidence of Na+ independent HCO3− uptake by the cyanobacterium Synechococcus leopoliensis. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:125–130. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie GS, Kandasamy RA. Monensin inhibition of Na+-dependent HCO3− transport distinguishes it from Na+-independent HCO3− transport and provides evidence for Na+/HCO3− symport in the cyanobacteria Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1419–1428. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie GS, Miller AG, Birch DG, Canvin DT. Simultaneous transport of CO2 and HCO3− by the cyanobacterium Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Physiol. 1988a;87:551–554. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.3.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie GS, Miller AG, Canvin DT. Characterization of the Na+ requirement in cyanobacterial photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1988b;88:757–762. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.3.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie GS, Miller AG, Canvin DT. Selective and reversible inhibition of active CO2 transport by hydrogen sulfide in a cyanobacterium. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:389–394. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, Badger MR, Berry JA. Photosynthesis and the intracellular inorganic carbon pool in the bluegreen alga Anabaena variabilis: response to external CO2 concentration. Planta. 1980;149:219–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00384557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, Zenvirth D, Marcus Y, Omata T, Ogawa T. Energization and activation of inorganic carbon uptake by light in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:210–213. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Canvin DT. Oxygen photoreduction and its effect on CO2 accumulation and assimilation in air-grown cells of Synechococcus UTEX 625. Can J Bot. 1997a;75:274–283. [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Canvin DT. Inorganic carbon accumulation stimulates linear electron flow to artificial electron acceptors of PSI in air-grown cells of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Physiol. 1997b;114:1273–1281. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.4.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinney G. Absorption of light by chlorophyll solutions. J Biol Chem. 1941;140:315–322. [Google Scholar]

- McEnery MW, Pederson PL. Diethylstilbestrol. A novel Fo-directed probe of the mitochondrial proton ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:1745–1752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Canvin DT. Glycolaldehyde inhibits CO2 fixation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus UTEX 625 without inhibiting the accumulation of inorganic carbon or the associated quenching of chlorophyll a fluorescence. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:1044–1049. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.3.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Espie GS, Canvin DT. Active transport of inorganic carbon increases the rate of O2 photoreduction. Plant Physiol. 1988a;88:6–9. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Espie GS, Canvin DT. Chlorophyll a fluorescence yield as a monitor of both active CO2 and HCO3− transport in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Physiol. 1988b;86:655–658. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.3.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Espie GS, Canvin DT. Active transport of CO2 by the cyanobacterium Synechococcus UTEX 625. Measurement by mass spectrometry. Plant Physiol. 1988c;86:677–683. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.3.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Espie GS, Canvin DT. The use of COS, a structural analog of CO2, to study active CO2 transport in the cyanobacteria Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:1221–1231. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.3.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Espie GS, Canvin DT. Physiological aspects of CO2 and HCO3− transport by cyanobacteria: a review. Can J Bot. 1990;68:1291–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Espie GS, Canvin DT. The effects of inorganic carbon and oxygen on fluorescence in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus UTEX 625. Can J Bot. 1991;69:1151–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T (1993) Molecular analysis of the CO2-concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. In H Yamamoto, C Smith, eds, Photosynthetic Response to the Environment, American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 113–125

- Ogawa T, Inoue Y. Photosystem I-initiated postillumination CO2 burst in a cyanobacterium, Anabaena variabilis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;724:490–493. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T, Miyano A, Inoue Y. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985a;808:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T, Omata T, Miyano A, Inoue Y (1985b) Photosynthetic reactions involved in the CO2-concentrating mechanism in the cyanobacterium, Anacystis nidulans. In WJ Lucas, JA Berry, eds, Inorganic Carbon Uptake by Aquatic Photosynthetic Organisms. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 287–304

- Price GD, Colman JR, Badger MR. Association of carbonic anhydrase activity with carboxysomes isolated from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7920. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:784–793. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.2.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie R, Nadolny C, Larkum AWD. Driving forces for bicarbonate transport in the cyanobacteria Synechococcus R-2 (PCC 7920) Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1573–1584. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.4.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salon C, Li Q, Canvin DT (1997) Glycolaldehyde inhibition of CO2 transport in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus UTEX 625. Can J Bot (in press)

- Salon C, Mir NA, Canvin DT. HCO3− and CO2 leakage from Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Cell Environ. 1996a;19:260–274. [Google Scholar]

- Salon C, Mir NA, Canvin DT. Influx and efflux of inorganic carbon in Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Cell Environ. 1996b;19:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Shelp BJ, Canvin DT. Evidence for bicarbonate accumulation by Anacystis nidulans. Can J Bot. 1984;62:1398–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Sültemeyer DF, Biehler K, Fock HP. Evidence for the contribution of pseudocyclic photophosphorylation to the energy requirement of the mechanism for concentrating inorganic carbon in Chlamydomonas. Planta. 1993;189:235–242. [Google Scholar]