Abstract

Purpose

Major peri-operative complications for adult spinal deformity (ASD) surgery remain common. However, risk factors have not been clearly defined. Our objective was to identify patient and surgical parameters that correlate with the development of major peri-operative complications with ASD surgery.

Methods

This is a multi-center, retrospective, consecutive, case–control series of surgically treated ASD patients. All patients undergoing surgical treatment for ASD at eight centers were retrospectively reviewed. Each center identified 10 patients with major peri-operative complications. Randomization tables were used to select a comparably sized control group of patients operated during the same time period that they did not suffer major complications. The two groups were analyzed for differences in clinical and surgical factors. Analysis was restricted to non-instrumentation related complications.

Results

At least one major complication occurred in 80 of 953 patients (8.4 %), including 72 patients with non-instrumentation related complications. There were no significant differences between the complications and control groups based on the demographics, ASA grade, co-morbidities, body mass index, prior surgeries, pre-operative anemia, smoking, operative time or ICU stay (p > 0.05). Hospital stay was significantly longer for the complications group (14.4 vs. 7.9 days, p = 0.001). The complications group had higher percentages of staged procedures (46 vs. 37 %, p = 0.011) and combined anterior–posterior approaches (56 vs. 32 %, p = 0.011) compared with the control group.

Conclusion

The major peri-operative complication rate was 8.4 % for 953 surgically treated ASD patients. Significantly higher rates of complications were associated with staged and combined anterior–posterior surgeries. None of the patient factors assessed were significantly associated with the occurrence of major peri-operative complications. Improved understanding of risk profiles and procedure-related parameters may be useful for patient counseling and efforts to reduce complication rates.

Keywords: Complications, Surgery, Adult, Spinal deformity, Risk factor

Introduction

The surgical treatment of adult spinal deformity is emerging as a significant healthcare issue. Demographic shifts in Western societies and quality of life expectations are driving a rapid expansion in the treatment of spinal pathologies. Age-related pathologies of the spine often represent a complex picture of degeneration related to the intervertebral discs, ligamentous supports, and facet joints. The degenerative cascade also involves loss of muscle tone and mass as well as loss of bone density. With the loss of structural support, deformity is a common progressive aspect of the aging spine. Adult spinal deformity is most commonly related to untreated adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, adult onset degenerative scoliosis, or primary sagittal imbalance. In a recent publication the prevalence of spinal deformity in older adults has been shown to exceed 60 % [1].

Surgical management of adult spinal deformity has traditionally been pursued for pain and disability that does not adequately respond to non-operative care [2–6]. However, several studies have demonstrated the lack of clinical effectiveness of non-surgical care with substantial costs to the healthcare system [7]. Surgical treatment of adult spinal deformity has been reported to be effective; however, it is associated with significant risks [8–10]. In addition, prior authors have found that the complications are similar in adults with either untreated adolescent idiopathic scoliosis or adult onset degenerative scoliosis [11, 12].

The care of patients with adult spinal deformity considering surgical treatment requires a cautious review of potential benefits against possible complications. While studies demonstrate the effectiveness of surgery in certain populations, the risk factors for a given patient remain poorly defined and thus limit an individualized risk–benefit ratio assessment to assist in decision-making for patient and surgeon alike.

The purpose of this study was to identify patient, peri-operative and surgical parameters that correlate with the development of major complications with adult spinal deformity surgery. Understanding the risk factors for complications allows the development of strategies to reduce their occurrence and facilitates the ability of both surgeon and patient to make better clinical decisions pertaining to surgical treatment for adult spinal deformity.

Materials and methods

Study design and inclusion criteria

This is a multi-center, retrospective review of patients who underwent surgical treatment for adult spinal deformity. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained at all eight participating sites prior to study initiation. Inclusion criteria were patients age 18 years or older who received spinal surgical treatment for adult spinal deformity.

The study developed two patient cohorts from the same time frame. A retrospective consecutive series of adult spinal deformity patients was reviewed and all patients who developed at least one major peri-operative complication occurring intra-operatively or up to 6 weeks following surgery were identified (complications group). All patients operated for ASD during the same time frame at each center were similarly identified. For each center, consecutive patients were included retrospectively until 10 patients with a major complication were identified. A randomization table was then used to select a similarly sized set of patients from enrolling sites that did not develop any major peri-operative complications (control group).

The definition of major complications used was as previously described by Carreon et al. [8] (Table 1). Patients with a primary major peri-operative complication related to instrumentation failure (e.g., rod fracture) were excluded from the analyses comparing complications and control groups, in order to focus these assessments on medical and operative complications, rather than biomechanical failures of instrumentation.

Table 1.

Intra- and post-operative major complications

| Intra-operative major complications | Post-operative major complications |

|---|---|

| Cardiac arrest | Bowel/Bladder deficit |

| Cord deficit | Death |

| Death | Deep vein thrombosis |

| Nerve root injury | Cauda equina deficit |

| Optic deficit/blindness | Infection-deep return to OR |

| Coagulopathy (DIC) | Motor deficit/paralysis |

| Vessel/organ injury | Myocardial infarction |

| Excessive bleeding if >4 L | Neuropathy |

| Malignant hyperthermia | Optic deficit/blindness |

| Pneumonia | |

| Pulmonary embolism | |

| Reintubation | |

| Sepsis | |

| Stroke | |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | |

| Acute respiratory failure | |

| Cholecystitis | |

| Pancreatitis | |

| Unplanned return to OR | |

| Prolonged ICU stay (>72 h) |

Modified from Carreon et al. [8]

The diagnosis of adult spinal deformity included a minimum of one of the following radiographic parameters: coronal Cobb angle greater than 30°, sagittal imbalance greater than 5 cm, coronal imbalance greater than 5 cm, thoracic kyphosis (sagittal Cobb angle from either T3 or T5 to T12) greater than 60°, thoracolumbar kyphosis (sagittal Cobb angle from T10 to L2) greater than 20°, and lumbar lordosis (sagittal Cobb angle from T12 to S1) less than 20°. We included patients with either untreated, progressive adolescent-onset idiopathic scoliosis or with adult onset de novo degenerative scoliosis. Prior studies have found that the complications are similar in adults with either untreated adolescent idiopathic scoliosis or adult onset degenerative scoliosis [11, 12].

Data collection

A retrospective chart review was performed at each site to identify patients who met inclusion criteria for the complications group and received surgery between 2002 and 2007. Medical records, surgical summary and office charts were all reviewed to gather data. Consecutive review was carried out retrospectively among all operatively treated ASD patients until 10 patients with major perioperative complications according to inclusion criteria were identified at each participating site. A total of 953 patients were reviewed across the eight centers to obtain 80 patients with major complications. The control group was selected based on a randomization table for each institution to gather a matched number of patients from the remaining 873 patients (953 − 80) treated during the same time span as the complications group. Patients in the control group underwent adult spinal deformity surgery but did not develop any major peri-operative complications.

Collected data included

Demographics: age, height (cm), weight (kg) and body mass index (BMI).

Pre-operative health status: blood pressure, heart rate, laboratory and urine analysis, co-morbidities, cardio-pulmonary evaluation, smoking habits, and the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grade.

Surgical data: surgical procedure, surgical approach, primary or revision surgery, same day or staged surgery, operative and anesthesia time, estimated blood loss (EBL), and presence or absence of a major intra-operative complication.

Hospital data: duration of intensive care unit (ICU) stay, total duration of hospital stay, and occurrence of major complications.

Post-operative data: office notes were reviewed to evaluate for major complications that occurred up to 6 weeks post-operatively.

Data were collected by research assistants who were not involved in the care of the patients and forwarded to the principal investigator (PI) site for data entry and quality control.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS software (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). Parameters with normal distribution were described using mean and standard deviation, while other parameters were described using median and interquartile range. Normality of data was determined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Frequency tables were used to present parameters such as co-morbidities and complication occurrences. Spearman and Pearson coefficients of correlations were used to evaluate correlation between total major complications and associated parameters. Differences in individual parameters between the complications group and control group were assessed using unpaired t tests and Chi-square tests.

Results

Between February 2002 and July 2007, 953 total patients received surgical treatment for ASD at the eight participating sites.

Demographics and pre-operative status

Ten consecutive patients with at least one major complication were identified at each site, generating 80 total patients for the complications group (Fig. 1). The primary major complication in eight of these patients was implant related (e.g., rod or screw fracture), instead of a primary medical or surgical complication, resulting in 72 patients being included in the complications group. The demographics of the complications group were as follows (Table 2): 54 females and 18 males, mean age of 54 years and mean BMI of 25.3 kg/m2. Mean number of co-morbidities per patient was 2.5 (SD = 1.85; range 0–6). The most common medical co-morbidities were hypertension (HTN), depression/anxiety, coronary artery disease (CAD) and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD). Seven patients (10 %) were ASA grade I, 28 patients (40 %) were ASA grade II, and 35 patients (50 %) were ASA grade III. The ASA grade was not available for the remaining two patients.

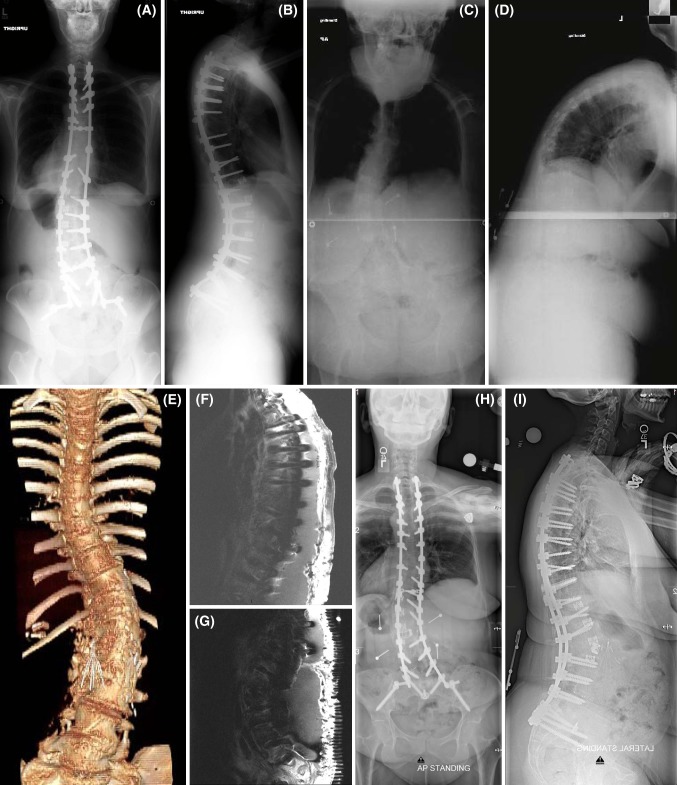

Fig. 1.

Case example of a patient surgically treated for adult deformity who had a major peri-operative complication. A 49-year-old woman with a history of untreated adolescent idiopathic scoliosis presented to an outside facility with back and leg pain and underwent a two-stage procedure: lateral interbody arthrodesis with mesh cages at T11–12, T12–L1, L2–3, and L3–4; followed by T4 to S1 posterior instrumented arthrodesis (stainless steel implants) with L4–5 and L5–S1 transforaminal interbody fusions (TLIF). Post-operative antero-posterior (AP) and lateral full-length X-rays are shown in a and b. This was complicated by a pulmonary embolism and a significant sacral abscess that ultimately required removal of all instrumentation. She presented to the study participant’s site approximately 1 year later with severe back and leg pain and difficulty walking (wheelchair bound) secondary to significant positive sagittal malalignment (C7 plumbline sagittal vertical axis of 23 cm). AP and lateral full-length X-rays are shown in c and d. Three-dimensionally reconstructed CT of the spine is shown in E. Note the caval filter placed following her first surgery. She underwent a 3-stage procedure: (1) L5–S1 anterior lumbar interbody fusion (2) T2 to S1 instrumentation with iliac screws and T4–T11 Smith-Petersen osteotomies, and (3) L2 pedicle subtraction osteotomy, L1–L2 TLIF, and T2–S1 arthrodesis. Within 2 months of surgery, she developed multi-drug resistant E. coli infection with significant and extensive wound fluid collection (f and g show T1-contrasted magnetic resonance images of the thoracic and lumbar spine). She was treated with multiple wound debridements, intravenous antibiotics, and ultimately a wound VAC. Despite this major peri-operative complication, at last follow-up (1 year from her 3-stage procedure), her wound is completely healed and she is off all pain medication, nearly pain free, and ambulating independently. Antero-posterior (AP) and lateral full-length X-rays from last follow-up are shown in h and i

Table 2.

Comparison of demographics and pre-operative parameters

| Parameter | Complications group | Control group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio F:M | 54:18 | 61:17 | ns |

| Age | 54 ± 16 | 52 ± 17 | ns |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 25.3 ± 6 | 26.9 ± 7 | ns |

| Number of co-morbidity | 2.5 ± 1.8 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | ns |

| ASA grade | 2.33 ± 0.7 | 2.43 ± 0.5 | ns |

| Percentage of revision cases (%) | 53 | 41 | ns |

| Number of previous surgeries | 1.9 | 1.7 | ns |

The control group of 80 patients (Table 2) was selected based on a randomization table of surgically treated adult spinal deformity patients who did not have complications during the same time period (2002–2007). Two of these patients were excluded due to insufficiency in their available data, leaving a total of 78 patients in the control group. The demographics of this control group were as follows: 61 females and 17 males, mean age 52 years and mean BMI 26.9 kg/m2. Mean number of co-morbidities per patient was 2.4 (standard deviation = 1.82; range 0–8). The most common medical co-morbidities in the control group were HTN, depression/anxiety, CAD and GERD. One patient (1 %) was ASA grade I, 36 patients (46 %) were ASA grade II, and 30 patients (38 %) were ASA grade III. The ASA grade was not available for the remaining nine patients.

No differences were noted between the complications and control groups in terms of demographics, co-morbidities, smoking status, pre-operative vitals, ASA grade, pre-operative anemia (hematocrit of 30 % or less), revision status, or number of previous surgeries (p > 0.05).

Incidence of complications

One or more major complications were observed in 80 of 953 patients (8.4 % major complication rate). After excluding the eight patients with a primary instrumentation related complication, the remaining 72 patients comprised the complications group. These 72 patients had a total of 99 major complications (average 1.4 per patient). The most common major complications were excessive blood loss (EBL > 4L, n = 11), return to the operating room for deep infection (n = 11), and symptomatic pulmonary embolus (n = 10).

Peri-operative parameters

In terms of peri-operative parameters (Table 3), group comparisons revealed that there were no significant differences in terms of operative time, revision status or length of ICU stay. However, the complications group exhibited significantly greater length of hospital stay (14.4 vs. 7.9 days, p = 0.001). Patients in the complications group had a significantly greater EBL than the control group (2.4 vs. 1.6 L, p = 0.004), however, the comparison of EBL between these groups is confounded, since excessive EBL is considered a major complication.

Table 3.

Comparison of peri-operative parameters

| Parameter | Complications group | Control group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Op time (mn) | 491 | 421 | ns |

| EBL (L) | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.004 |

| ICU stay (days) | 3.4 | 2.8 | ns |

| Hospital stay (days) | 14.4 | 7.9 | 0.001 |

Estimated blood loss (EBL) is significantly different between complications and control groups; however, this result is confounded by the inclusion of excessive EBL as a major complication

Surgical approach and staging

In terms of surgical approach (Table 4), significant differences were also noted between the complications and control groups. The complications group exhibited a higher percentage of staged procedures (46 vs. 37 %, p = 0.011), and a higher percentage of anterior/posterior approaches (56 vs. 32 %, p = 0.011) (Figs. 2 and 3).

Table 4.

Comparison of surgical parameters

| Parameter | Complications group | Control group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage single stage (%) | 54 | 63 | 0.011 |

| Stages (mean number) | 1.5 | 1.4 | ns |

| Posterior-only approach (%) | 38 | 60.3 | 0.011 |

| Anterior-only approach (%) | 5.6 | 7.7 | |

| Anterior-posterior approach (%) | 56.3 | 32.1 |

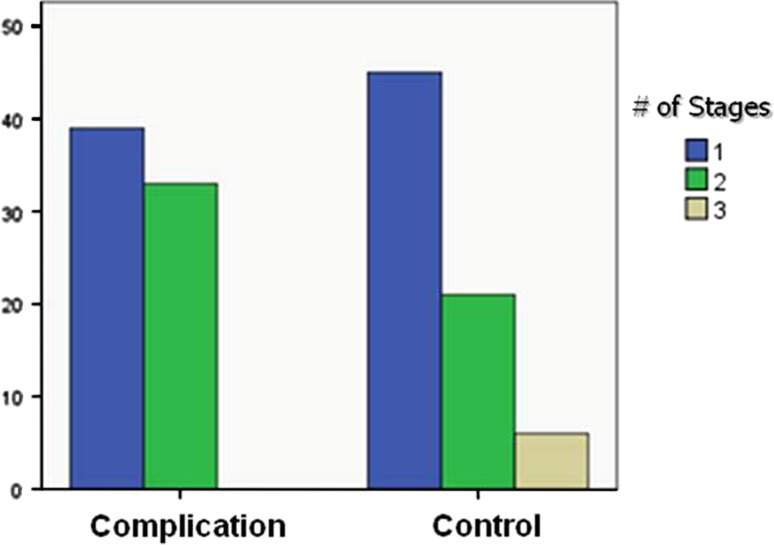

Fig. 2.

Patient distribution per number of stages. The complications group was more likely to have a staged procedure than the control group (p = 0.011)

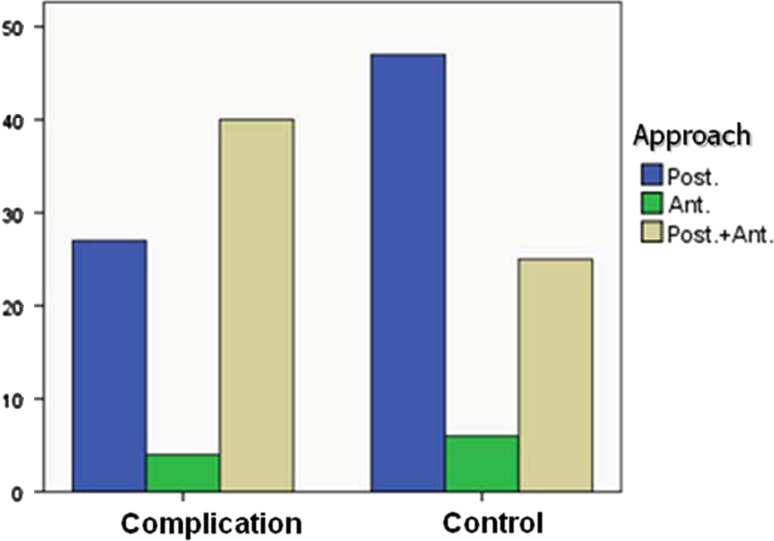

Fig. 3.

Patient distribution per surgical approach. The complication group was more likely to have combined anterior-posterior approached than the control group (p = 0.011)

Discussion

Risk scoring is frequently used to identify patients at risk for adverse outcomes. Commonly used risk-scoring schemes include the ASA physical status class, the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE), the Injury Severity Score (ISS) and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) [13–15]. These systems quantify the severity of patient illness, and have been shown to predict risk for morbidity and mortality associated with trauma and/or surgery [15, 16]. More recently, the Physiological and Operative Severity Score for Enumeration of Mortality and Morbidity (POSSUM) has been developed and validated to predict mortality and morbidity for patients undergoing colorectal surgery or vascular surgery and has been modified for applications to orthopedic surgery [17]. The theoretical benefits of a risk-scoring system, especially a system that is designed for a specific surgical field or clinical interest, include identification and potential optimization of physiologic risk factors, improved patient counseling on the risk/benefit ratio of surgery, improved outcome analysis between patients and providers, and reduction in peri-operative complications.

The benefits of surgical treatment for adult spinal deformity have been established; surgical patients report greater reduction of total pain, leg pain, self-image and function compared to adult spinal deformity patients treated nonoperatively [9, 18–21]. However, despite the benefits afforded to adult spinal deformity patients via operative management, the major hurdles to adult spinal deformity surgery are the physiologic and economic costs. These costs are manifest by the reported high complication rates and resource utilization following adult spinal deformity surgery. Reduction of adult spinal deformity surgical complications requires improvement in patient selection and more efficacious procedure selection. While there are multiple potential pathologies in adult spinal deformity, including spinal stenosis, lateral listhesis, sagittal instability, and sagittal and coronal imbalance [20, 22], few concrete guidelines for surgical management exist. An adult spinal deformity risk-scoring system that quantifies the impact that a specific patient parameter and a particular surgical procedure have upon the complication risk profile may improve patient and procedure selection.

The purpose of this study was to identify profiles of patients who experienced major complications following surgery for adult spinal deformity. Multi-center review of 953 consecutive adult spinal deformity patients treated surgically identified 80 patients who suffered at least one major complication. The 8.4 % major complication rate reported in this study is consistent with previous reports [23–25]. Such rates should be placed in the perspective of the complex medical histories noted in patients undergoing surgery for adult spinal deformity. In the present study, the mean ASA grade for the control and complications groups were 2.43 and 2.33, respectively, and mean number of co-morbidities were 2.4 and 2.5, respectively. Additionally, the number of previous surgeries by group was 1.7 and 1.9, respectively, for control and complications groups. The elevated mean ASA scores and previous surgery rate in both groups may explain the lack of correlation between these parameters and the occurrence of complications due to a ceiling effect. It is rare for elective surgery related to adult spinal deformity to occur in the setting of an ASA grade of IV or V, as it is uncommon for patients to undergo a fourth or fifth surgery for adult spinal deformity.

In the current study, no significant differences were noted between the complications and control groups with regard to ICU stay and operative time. This may relate to the complex nature of adult spinal deformity surgery which routinely involves lengthy operative time and ICU stay. Only EBL was found to be significantly greater in the complications group (2.4 vs. 1.6 L for control group, p = 0.004), however, this finding is confounded, since excessive EBL was classified as a major complication. In other studies, increased EBL has been shown to increase risk for early post-operative complications [26–28]. Although obesity has been previously reported to increase the risk of complications following adult spinal deformity surgery [29], in the present study there was no significant difference in the mean BMI between patients who did and did not experience a major complication.

A significant correlation between staging, surgical approach and major peri-operative complications was found in this study. In terms of staging, nutritional depletion and metabolic disarray from a first intervention can limit physiologic resilience for a second procedure. This is supported by a previous large study by Fang et al. [30] demonstrating that post-operative spine related infections were correlated with staging and multiple surgical approaches. In a smaller series Rhee et al. [31] found that staging posterior-only surgery in adult spinal deformity apparently did not lead to greater complications. This is of potential clinical importance given that many patient-related parameters cannot be modified (co-morbidities, deformity parameters and thus case complexity), whereas surgical approach and staging can often be controlled by the surgical team.

The primary limitation of the present study is the retrospective design. We have tried to mitigate this limitation by evaluating patients with complications in a consecutive and multi-center study design. In addition, we have included a control group that was established by randomization from each of the participating centers. Future study on this topic should include a prospective enrollment of consecutive cases and a larger patient pool.

Conclusion

This study offers a critical analysis of consecutive patients that underwent adult spinal deformity surgery and developed major peri-operative complications. An incidence of 8.4 % for major complications among 953 consecutive patients was noted. While co-morbidities, ASA grade, and demographic factors did not demonstrate significant correlation with complications, controllable surgery related parameters did. Staging and multiple surgical approaches in one setting were significantly linked to occurrence of major peri-operative complications. Further study directed at defining risk profiles and procedure-related parameters could have significant impact on pre-operative risk–benefit surgical discussions and pre-emptive approaches to reduce complications.

Acknowledgment

Research grant from DePuy to fund the International Spine Study Group. IRB approval was obtained from all contributing institutions.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Schwab F, Dubey A, Pagala M, Gamez L, Farcy JP. Adult scoliosis: a health assessment analysis by SF-36. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:602–606. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000049924.94414.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu KM, Smith JS, Sansur CA, Shaffrey CI. Standardized measures of health status and disability and the decision to pursue operative treatment in elderly patients with degenerative scoliosis. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:42–47. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000361999.29279.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JS, Fu KM, Urban P, Shaffrey CI. Neurological symptoms and deficits in adults with scoliosis who present to a surgical clinic: incidence and association with the choice of operative versus nonoperative management. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:326–331. doi: 10.3171/SPI.2008.9.10.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aebi M. The adult scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:925–948. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aebi M. Correction and stabilization of a double major adult idiopathic scoliosis from T5/L5. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:510–512. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1349-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aebi M. Less invasive approach to degenerative lumbar deformity surgery. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:571–572. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2206-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glassman SD, Carreon LY, Shaffrey CI, Polly DW, Ondra SL, Berven SH, Bridwell KH. The costs and benefits of nonoperative management for adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:578–582. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b0f2f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carreon LY, Puno RM, Dimar JR, 2nd, Glassman SD, Johnson JR. Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2089–2092. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith JS, Shaffrey CI, Glassman SD, Berven SH, Schwab FJ, Hamill CL, Horton WC, Ondra SL, Sansur CA, Bridwell KH. Risk–benefit assessment of surgery for adult scoliosis: an analysis based on patient age. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:817–824. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e21783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamartina C, Petruzzi M. Adult de novo lumbar scoliosis. Posterior instrumented fusion with Smith-Peterson osteotomy, decompression and management of postoperative infection. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:1580–1581. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1941-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sansur CA, Smith JS, Coe JD, Glassman SD, Berven SH, Polly DW,, Jr, Perra JH, Boachie-Adjei O, Shaffrey CI. Scoliosis Research Society Morbidity and Mortality of adult scoliosis surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:593–597. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182059bfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwab F, Farcy JP, Bridwell K, Berven S, Glassman S, Harrast J, Horton W. A clinical impact classification of scoliosis in the adult. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:2109–2114. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231725.38943.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aso A. New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology. 1963;24:111. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W, Jr, Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14:187–196. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, Zimmerman JE, Bergner M, Bastos PG, Sirio CA, Murphy DJ, Lotring T, Damiano A, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100:1619–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hariharan S, Zbar A. Risk scoring in perioperative and surgical intensive care patients: a review. Curr Surg. 2006;63:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohamed K, Copeland GP, Boot DA, Casserley HC, Shackleford IM, Sherry PG, Stewart GJ. An assessment of the POSSUM system in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:735–739. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B5.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bridwell KH, Glassman S, Horton W, Shaffrey C, Schwab F, Zebala LP, Lenke LG, Hilton JF, Shainline M, Baldus C, Wootten D. Does treatment (nonoperative and operative) improve the two-year quality of life in patients with adult symptomatic lumbar scoliosis: a prospective multicenter evidence-based medicine study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2171–2178. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a8fdc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li G, Passias P, Kozanek M, Fu E, Wang S, Xia Q, Li G, Rand FE, Wood KB. Adult scoliosis in patients over sixty-five years of age: outcomes of operative versus nonoperative treatment at a minimum two-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2165–2170. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b3ff0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith JS, Shaffrey CI, Berven S, Glassman S, Hamill C, Horton W, Ondra S, Schwab F, Shainline M, Fu KM, Bridwell K. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of leg pain in adults with scoliosis: a retrospective review of a prospective multicenter database with two-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:1693–1698. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ac5fcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JS, Shaffrey CI, Berven S, Glassman S, Hamill C, Horton W, Ondra S, Schwab F, Shainline M, Fu KM, Bridwell K. Improvement of back pain with operative and nonoperative treatment in adults with scoliosis. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:86–93. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000347005.35282.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bess S, Boachie-Adjei O, Burton D, Cunningham M, Shaffrey C, Shelokov A, Hostin R, Schwab F, Wood K, Akbarnia B. Pain and disability determine treatment modality for older patients with adult scoliosis, while deformity guides treatment for younger patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2186–2190. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b05146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baron EM, Albert TJ. Medical complications of surgical treatment of adult spinal deformity and how to avoid them. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:S106–S118. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000232713.69342.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eck KR, Bridwell KH, Ungacta FF, Riew KD, Lapp MA, Lenke LG, Baldus C, Blanke K. Complications and results of long adult deformity fusions down to l4, l5, and the sacrum. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:E182–E192. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200105010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapp MA, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Baldus C, Blanke K, Iffrig TM. Prospective randomization of parenteral hyperalimentation for long fusions with spinal deformity: its effect on complications and recovery from postoperative malnutrition. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:809–817. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200104010-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho KJ, Suk SI, Park SR, Kim JH, Kim SS, Choi WK, Lee KY, Lee SR. Complications in posterior fusion and instrumentation for degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2232–2237. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31814b2d3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen MA, Nepple JJ, Riew KD, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Mayfield J, Fraser VJ. Risk factors for surgical site infection following orthopaedic spinal operations. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2008;90:62–69. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu SS. Blood loss in adult spinal surgery. Eur Spine J. 2004;13(Suppl 1):S3–S5. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0753-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pull ter Gunne AF, Laarhoven CJ, Cohen DB. Incidence of surgical site infection following adult spinal deformity surgery: an analysis of patient risk. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:982–988. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1269-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang A, Hu SS, Endres N, Bradford DS. Risk factors for infection after spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1460–1465. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166532.58227.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhee JM, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Baldus C, Blanke K, Edwards C, Berra A. Staged posterior surgery for severe adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:2116–2121. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000090890.02906.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]