Abstract

Background

Despite the major benefits of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) on HIV-related survival, there is an ongoing need to help alleviate medication side effects related to ART use. Initial studies suggest marijuana use may reduce HIV-related symptoms, but medical marijuana use among HIV-infected individuals has not been well described.

Methods

We evaluated trends in marijuana use and reported motivations for use among 2,776 HIV-infected women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) between October 1994 and March 2010. Predictors of any and daily marijuana use were explored in multivariate logistic regression models clustered by person using GEE. In 2009 participants were asked if their marijuana use was medical, “meaning prescribed by a doctor”, or recreational, or both.

Results

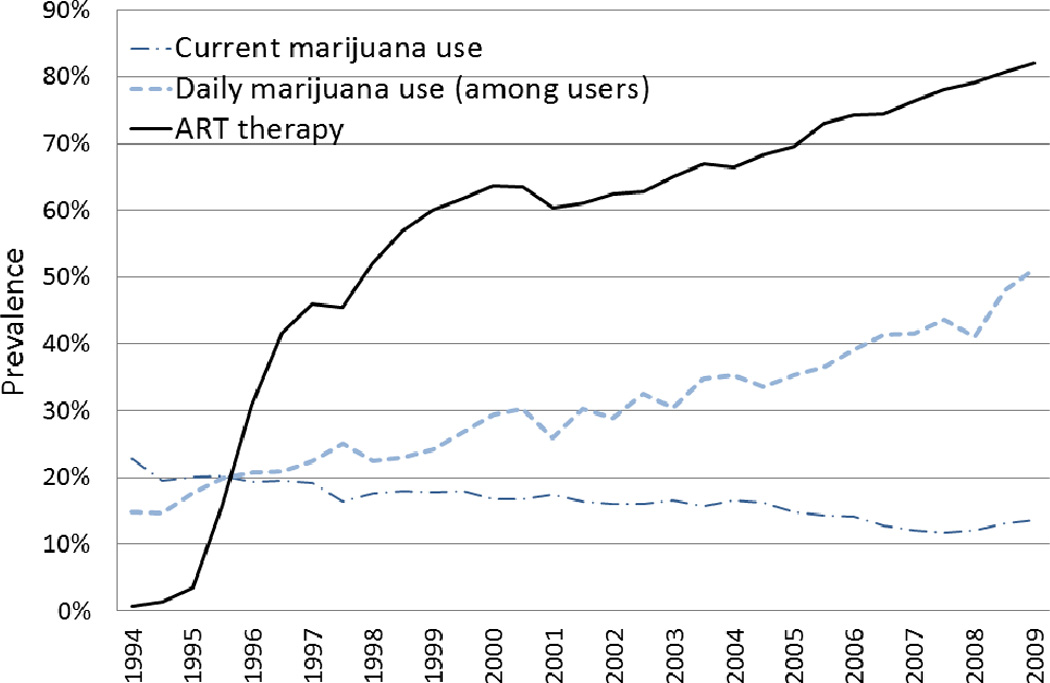

Over the sixteen years of this study the prevalence of current marijuana use decreased significantly from 21% to 14%. In contrast, daily marijuana use almost doubled from 3.3% to 6.1% of all women, and from 18% to 51% of current marijuana users. Relaxation, appetite improvement, reduction of HIV-related symptoms, and social use were reported as common reasons for marijuana use. In 2009, most marijuana users reported either purely medicinal use (26%) or both medicinal and recreational usage (29%). Daily marijuana use was associated with higher CD4 cell count, quality of life, and older age. Demographic characteristics and risk behaviors were associated with current marijuana use overall, but were not predictors of daily use.

Conclusion

This study suggests that both recreational and medicinal marijuana use are relatively common among HIV-infected women in this U.S.

Keywords: marijuana, cannabis, HIV, medicinal

INTRODUCTION

HIV infected individuals experience a wide range of medical and psychiatric co-morbidities such as neuropathy, anxiety and depression, as well as adverse side effects associated with antiretroviral treatment.1–4 Users of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) experience a range of symptoms including neuropathic pain, nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, disturbed sleep, depression and anxiety, and physical sickness; these factors are cited as a common reason for delaying, missing, and discontinuing doses of ART.5 Despite the major benefits of ART on HIV-related survival,6 there is an ongoing need to help alleviate medication side effects in order to ensure the long term adherence to antiretroviral treatments that is necessary for optimal health outcomes.

Initial randomized controlled studies of HIV-infected individuals with peripheral neuropathy suggest significant reduction of pain with daily marijuana use compared to placebo.7, 8 The substance in marijuana thought to produce these beneficial effects is delta-9-THC. Several pharmaceutical oral formulations of delta-9-THC are currently FDA approved for treatment of loss of appetite in AIDS as well as chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, including Marinol and Dronabinol. 3, 9, 10 Although Marinol and Dronabinol have been approved for use in AIDS since 1992, frequency of medical marijuana use among HIV-infected individuals has not been well studied.

Observation studies of HIV-infected individuals in the U.S. have reported both that current marijuana use is relatively common (12–27%) and that its use may reduce HIV-related symptoms.3, 8, 11, 12 Prevalence of marijuana use in the general U.S. population, by contrast, is between 3–7%.13, 14 In a Canadian study, where cannabis has been legal for medicinal use in HIV since 2001, 61% of HIV-infected individuals classified themselves as current medical cannabis users (defined in that study as using marijuana as a means to cope with their illness or symptoms).4 The demand for medical marijuana appears to be significant, but given that medicinal use is illegal in the majority of U.S. states, this presents a challenge to U.S. drug policy.15

A previous study in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), a multisite longitudinal observational study of HIV infection among U.S. women, reported a high prevalence (72%) of lifetime marijuana use.16 Furthermore, a substantial subgroup currently used marijuana at least weekly, and 13% of the 2,308 WIHS women who were not weekly marijuana users at study baseline initiated weekly use between 1994 and 2000.16 We now extend this previous study to evaluate longitudinal patterns of marijuana use, as well as predictors and motivators of use over a 16-year period during which effective ART came into common use. Since the use of marijuana among chronically ill persons seems to be frequent and ongoing in the U.S., it is important to understand factors that influence use as well as the outcomes related to marijuana use.

METHODS

Study Population

The present study utilizes data from 2,776 HIV-infected women who participated in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) between October 1994 and March 2010 and answered questions on marijuana use. WIHS participants are drawn from six study sites in the San Francisco Bay Area, southern California, Bronx, Brooklyn, Chicago, and Washington DC.17, 18 Women were recruited in 1994–95 and again in 2001–02 from a variety of venues including HIV care clinics and testing sites, community outreach, research and drug rehabilitation programs. Of the 2,776 HIV-infected women enrolled, 966 (35%) had died by 2010. Of the 1,810 women still alive after up to 15 years of participation, 1377 (76%) were still actively participating in the study in 2010; retention strategies have been described elsewhere.19, 20

Measures

Interviewer-administered questionnaires are administered twice annually in WIHS, and data are routinely collected on the use of recreational and therapeutic drugs, alcohol, and cigarettes over the past six months (called recent use hereafter). Questions assess the prevalence and frequency of current marijuana use. Recent marijuana use was assessed by asking participants: “Since your last visit have you used marijuana or hash?” Frequency of use was assessed by asking, “On average, how often did you use marijuana or hash since your last visit?” Validity of self-reported drug use has been shown in multiple studies,21 although some studies suggest higher reporting of drug use using computer assisted self-interview.22

Between 2004–2008 additional questions on reasons for marijuana use were added to the WIHS interview. Four specific reasons for marijuana use were queried at each visit 2004–08: to relax, for social situations, to reduce HIV symptoms, and to increase appetite (each yes/no answer). Respondents reporting marijuana use for other reasons were also asked to describe those reasons with open text responses that were then grouped into meaningful categories. The range of reasons for use was similar at each visit and therefore only the cumulative prevalence of each reason are reported. Marijuana users on ART were also asked whether their marijuana affected how they took their ART medication (yes/no). In 2009 a question on medicinal marijuana use was added for all women reporting recent marijuana use; this question asked women whether their use of marijuana was “medical, meaning prescribed by a doctor, or recreational, or both.”

Each study visit also included collection of demographic, psychosocial, and biological variables as well as a physical examination and labs which include CD4 T-cell count and HIV viral load. The definition of ART was guided by the DHHS/Kaiser Panel 23 and is defined as: the reported use of three or more antiretroviral medications, one of which has to be a protease inhibitor (PI), a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), an integrase inhibitor, or an entry inhibitor, with one of the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) abacavir or tenofovir.

Covariates of interest included the following HIV-related variables: CD4 cell count tested at every visit (continuous), antiretroviral therapy (ART) use in the past six months (yes, no); and, among those on ART, adherence to the regimen defined as a self-report of taking antiretroviral drugs as prescribed ≥95% of the time. In addition, we evaluated co-morbidities including self-reported peripheral neuropathy defined as “since your last visit have you experienced numbness, tingling or burning sensations in your arms, legs, hands or feet that lasted for more than two weeks”; self-reported asthma; symptoms of depression assessed via Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) where a CESD≥16 is defined as a high level of symptoms 24; diabetes defined by self-report, taking diabetes medication or having serum glucose >125; and self-reported quality of life (QOL) rated using a shortened Medical Outcome Study-HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 25, 26, where 6 or higher was defined as good perceived health. In addition we asked about any use in the past six months of: tobacco, cocaine, and injection drug use, as well as the number of sexual partners in the past six months and condom use during the past six months (always, sometimes, never) as measures of sexual risk taking; and age. Race and ethnicity were categorized as White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, other race non-Hispanic, and Hispanic any race. As results were similar for Hispanics of any race and White non-Hispanics they were grouped together in the final analyses. IRB approval was obtained at each study site and informed consent obtained from each participant.

Statistical Analysis

We describe participant characteristics at study baseline (which was 1994/5 for 74% of the women and was 2001/2 for the remaining women) and in 2010. Prevalence of current marijuana use was plotted over calendar time.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models clustered by person using GEE were used to evaluate risk factors for current marijuana use (defined as marijuana use since the last visit) at semi-annual visits between 1994 and 2010. Three separate models considered i) any current marijuana use (yes/no), ii) current daily marijuana use (daily compared to <daily or no use, and iii) current marijuana use among marijuana users (daily compared to <daily use) as outcomes. Heavy marijuana use was defined as daily marijuana use in the past six months.27, 28 We were especially interested in the association between ART use/adherence and marijuana use, as marijuana use has been reported to help alleviate some ART related side effects and might therefore increase adherence. At each visit, covariates of interest at the same visit were compared to marijuana use at that visit. These models included the following time updated variables: age, CD4 cell count, HIV-status, ART use in the past six months, ART adherence, current peripheral neuropathy, asthma, depression symptoms, diabetes, quality of life, current tobacco, cocaine, and injection drug use, recent number of sexual partners and recent condom use. Race/ethnicity, study site and enrollment wave into study were also included in these models. Univariate odds ratio (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were reported. All variables significant in univariate analysis (p<0.10) and variables of a-priori interest were included in the multivariate models and removed in a stepwise fashion. Final multivariate models for each outcome retained all statistically significant variables as well as those variables of interest from previous research (including age, race, current CD4, current ART use, depression and ART adherence) as well as variables significant in the other outcome models, for comparison. The association of current marijuana use (as an exposure) on increased odds of ART adherence (as an outcome) was similarly modeled. All analysis was done using Stata 11.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population at enrollment

A total of 2,776 HIV-infected women were enrolled in the WIHS in the two enrollment waves (1994–95 and 2001–02) and completed baseline study surveys. Participants were primarily Black non-Hispanic (56%), Hispanic (26%), and White non-Hispanic (15%, Table 1). At enrollment, the median age was 35.6 years, 66.5% reported ever having used marijuana and 21.4% reported marijuana use in the past six months. At study baseline, current marijuana use varied by study site from 16–19% of participants at the D.C., Los Angeles, and Brooklyn sites to 25– 29% of participants at the Bronx, Chicago and San Francisco sites, respectively (p<0.001). Heavy (daily) marijuana use at baseline was uncommon (3.8% of all participants); half (50%) of current marijuana users reported only occasional (less than weekly) use, 33% reported weekly use, and only 18% reported daily use (Table 1). There were 43,540 person-visits included in this analysis, with a median of 16 visits per woman (IQR=6–26), and a median of six months between study visits.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-infected WIHS participants at study entry and in 2010.

|

Baseline n=2776 |

Visit 31 (Oct 2009–Mar 2010) N=1377 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % | n | % |

| Median age (in years) | 36 years | 46 years | ||

| Year enrolled | ||||

| 1994–1995 | 2044 | 74% | 846 | 61% |

| 2001–2002 | 732 | 26% | 531 | 39% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 423 | 15% | 188 | 14% |

| African American (Non-Hispanic) | 1547 | 56% | 752 | 55% |

| Hispanic Ethnicity, any race | 716 | 26% | 385 | 28% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander/ other | 90 | 3% | 52 | 4% |

| COMORBIDITIES AND QUALITY OF LIFE | ||||

| Median HIV viral load, units | 12,000 | undetectable | ||

| Median CD4 cell count, units | 372 | 497 | ||

| Currently on HAART | 403 | 15% | 1131 | 82% |

| Have peripheral neuropathy | 702 | 25% | 277 | 20% |

| Have asthma | 526 | 19% | 61 | 4% |

| Depressed (CESD≥16) | 1473 | 53% | 380 | 31% |

| Report good quality of life (QOL) | 1639 | 59% | 721 | 57% |

| RISK BEHAVIOR in past six months | ||||

| Used tobacco | 1420 | 51% | 460 | 37% |

| Used cocaine | 323 | 12% | 14 | 1.1% |

| Injected drugs | 224 | 8% | 7 | 0.6% |

| Number of sexual partners | ||||

| 0 | 756 | 27% | 291 | 40% |

| 1 | 1549 | 56% | 685 | 55% |

| ≥ 2 | 456 | 17% | 64 | 5% |

| Used marijuana or hash? | 594 | 21% | 170 | 14% |

| Frequency of marijuana use (among users) | ||||

| Less than once a month | 173 | 29% | 20 | 12% |

| > Once a month, but ≤ once a week | 186 | 31% | 30 | 17% |

| 2–6 times a week | 128 | 22% | 33 | 19% |

| Once a day | 59 | 10% | 31 | 18% |

| More than once a day | 46 | 8% | 56 | 33% |

Trends in marijuana use among HIV-infected women, 1994–2010

Over the sixteen years of this study the prevalence of current marijuana use decreased significantly from 23% to 14% (p<0.001, Figure 1), as participants aged. This included a decrease in marijuana use among both HIV-infected women on ART (22% to 12%) and HIV-infected women not on ART (22% to 15%). In contrast, the occurrence of daily marijuana use almost doubled over the same time period, from 3.3% to 6.1% of all women. Among current marijuana users the increase in daily marijuana was even more dramatic, changing from 14.8% of current marijuana users at study entry to 51% of current marijuana users in 2010 (p-trend ≤0.001, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Daily marijuana use increased significantly during the course of the study at each of the study sites. This increase was most notable in the San Francisco study site where daily marijuana use increased from 5.1% of all participants in 1994 to 14.3% in 2010; at the other study sites prevalence of daily marijuana use increased from 1.7–4.5% of all women at baseline to 2.8–6.9% of women in 2010. During the study, the proportion of HIV-infected women currently using marijuana also varied considerably by site (p<0.001). The average prevalence of current marijuana during the 14 year study was 27% in San Francisco, 19% in Chicago, and 12–15% at the remaining 4 sites

Reported reasons for current marijuana use

In 2009–10, marijuana users were asked whether their use was recreational or medicinal (defined in the survey as being prescribed by a doctor). The majority of marijuana users reported some medicinal marijuana use, including 26% of users reporting purely medicinal use and another 29% of users reporting both medicinal and recreational usage,Table 2. Medicinal marijuana use was even more common among heavy marijuana users; among daily marijuana users, more than two-thirds reported some medicinal marijuana use, Table 2. While medicinal marijuana use was common among HIV-infected marijuana users, it remained rare in the study population overall, with 7.1% of women at the 2010 study visit reporting current medicinal marijuana use.

Table 2.

Self-Reported Reasons for current marijuana use (any and daily use) among HIV-infected women in the WIHS who reported marijuana use in the past six months at their V31 study visit (October 2009 – March 2010).

| Reasons reported for current marijuana use | Any current marijuana use |

Current daily marijuana use |

|---|---|---|

| Among those using marijuana in past six months (at V31) | N=170 | N=87 |

| Was your use of marijuana medical meaning prescribed by a doctor, or recreational? | ||

| Recreational only | 45% | 31% |

| Medical only | 26% | 28% |

| Both medical and recreational | 29% | 41% |

| Does your use of marijuana affect how you take your HIV medication? | ||

| No | 98.5% | 98.4% |

| Yes | 1.5% | 1.6% |

| Among those reporting recent marijuana use at any visit 2004–2008 | N=419 | N=208 |

| Of the marijuana you consumed, did you use it for any of the following?: | ||

| To relax or reduce stress | 85% | 82% |

| To increase appetite because of weight loss | 58% | 76% |

| To reduce HIV symptoms such as nausea | 38% | 52% |

| To better appreciate a social situation | 41% | 44% |

| Additional reasons reported as motivators for use | ||

| Recreational Use | 16% | 2% |

| Physical pain relief | 16% | 6% |

| Mental health relief | 8% | 0% |

| Sleep aid | 4% | 3% |

More general reasons for marijuana use were asked between 2004 and 2008, with participants asked to indicate all reasons that applied to their marijuana use. The most common reasons reported for marijuana use were: relaxation (85% of current marijuana users), appetite stimulation (58%), for social situations (41%), and for reduction of HIV symptoms (38%). Less common reasons reported for use included recreational use, physical pain relief, for mental health reasons, and as a sleep aid (Table 2). Among those using marijuana daily, use for relaxation and social situations were also common,Table 2. However, daily marijuana users were more likely than less frequent marijuana users to report use for appetite stimulation (76% vs 49%, p<0.001) or for reduction of HIV symptoms (52% vs 31%, p<0.001). Marijuana users consistently reported that their marijuana use did not affect how they took their HIV medications.

Factors associated with marijuana use in longitudinal analysis

Table 3 explores risk factors for current and daily marijuana use in longitudinal multivariate models of data collected between1994–2010. These models are adjusted for time-updated measures of current CD4 cell count, ART use and adherence, age, peripheral neuropathy, asthma, depression, quality of life, body-mass index, tobacco use, cocaine use, number of recent sexual partners, recent condom use, as well as race/ethnicity and study site. Current marijuana users at each visit were significantly less likely than non-users to be on ART (aOR=0.77,95%CI=0.68–0.87), and less likely to be adherent to ART (aOR=0.58, 95%CI=0.48–0.71). Current marijuana use was also associated with demographic factors, underweight and co-morbidity, and other risk behaviors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Longitudinal analysis of risk factors associated with current and daily marijuana use among 2776 HIV-infected women in the WIHS between 1994–2010.

| Risk Factors | Prevalence of any marijuana use across all visits |

OR (95%CI) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any current marijuana use | Current Daily Marijuana Use | ||||||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Multivariate (among marijuana users only) |

|||||||

| Current CD4 cell count: | |||||||||||

| < 500 | 17.20% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| ≥ 500 | 15.70% | 0.84 | (0.75–0.94) | 0.97 | (0.85–1.10) | 1.10 | (0.94–1.30) | 1.21 | (1.00–1.44) | 1.24 | (1.01–1.53) |

| Currently on ART | |||||||||||

| No | 19.80% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 14.10% | 0.55 | (0.50–0.61) | 0.77 | (0.68–0.87) | 1.09 | (0.95–1.27) | 1.00 | (0.84–1.20) | 1.16 | (0.96–1.42) |

| Adherent to ART (among ART users)* | |||||||||||

| No (<95% of the time) | 19.60% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes (≥95% of the time) | 12.40% | 0.54 | (0.46–0.64) | 0.58 | (0.48–0.71) | 0.72 | (0.57–0.91) | 0.81 | (0.61–1.07) | 1.24 | (0.90–1.71) |

| CO-MORBIDITIES | |||||||||||

| Peripheral Neuropathy | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| No | 15.80% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.12 | (0.92–1.36) | 1.03 | (0.83–1.30) | |||

| Yes | 20.00% | 1.18 | (1.05–1.32) | 1.16 | (1.02–1.32) | 1.13 | (0.96–1.34) | ||||

| Asthma | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| No | 16.20% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.32 | (0.97–1.79) | 1.18 | (0.84–1.68) | |||

| Yes | 24.50% | 1.48 | (1.25–1.74) | 1.24 | (1.01–1.51) | 1.22 | (0.94–1.59) | ||||

| Depressed | |||||||||||

| No | 13.90% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 20.10% | 1.50 | (1.36–1.65) | 1.35 | (1.19–1.52) | 1.40 | (1.19–1.64) | 1.36 | (1.14–1.62) | 1.16 | (0.94–1.43) |

| Good quality of life reported | |||||||||||

| No | 20.50% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 15.00% | 0.88 | (0.86–0.91) | 0.81 | (0.72–0.92) | 0.84 | (0.72–0.99) | 1.35 | (1.09–1.68) | 1.33 | (1.08–1.63) |

| Body mass index (BMI) | |||||||||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 28.90% | 1.61 | (1.24–2.08) | 1.47 | (1.09–2.00) | 1.97 | (1.36–2.85) | 1.88 | (1.25–2.81) | 1.56 | (1.07–2.52) |

| Normal (18.5–25) | 20.60% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Overweight (25–30) | 15.40% | 0.53 | (0.46–0.61) | 0.58 | (0.50–0.68) | 0.65 | (0.53–0.80) | 0.73 | (0.58–0.91) | 0.89 | (0.69–1.13) |

| Obese (>30) | 12.30% | 0.29 | (0.24–0.35) | 0.36 | (0.29–0.44) | 0.50 | (0.38–0.66) | 0.54 | (0.40–0.73) | 0.97 | (0.70–1.33) |

| RISK BEHAVIORS | |||||||||||

| Current tobacco use | |||||||||||

| No | 9.60% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 24.60% | 4.29 | (3.69–5.00) | 3.24 | (2.74–3.83) | 2.13 | (1.74–2.60) | 1.96 | (1.54–2.47) | 0.94 | (0.72–1.24) |

| Current cocaine use | |||||||||||

| No | 15.40% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 46.50% | 5.07 | (4.22–6.09) | 3.63 | (2.96–4.53) | 1.66 | (1.25–2.19) | 1.55 | (1.12–2.14) | 0.75 | (0.54–1.05) |

| Number of sex partners in last six mo. | |||||||||||

| 0 | 13.70% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| 1 | 15.40% | 1.64 | (1.45–1.83) | 1.34 | (1.16–1.56) | 1.14 | (0.95–1.36) | 1.00 | (0.76–1.31) | 1.00 | (0.76–1.30) |

| 2–3 | 40.00% | 3.09 | (2.64–3.62) | 2.11 | (1.73–2.57) | 1.36 | (1.07–1.75) | 0.98 | (0.69–1.37) | 0.97 | (0.69–1.37) |

| ≥4 | 47.00% | 9.62 | (7.36–12.6) | 5.06 | (3.65–7.02) | 1.80 | (1.19–2.72) | 0.74 | (0.49–1.29) | 0.74 | (0.44–1.24) |

| Condom use last 6 months | |||||||||||

| Always / No sex | 14.50% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Sometimes | 22.10% | 1.91 | (1.69–2.17) | 1.41 | (1.21–1.65) | 1.43 | (1.18–1.75) | 1.46 | (1.17–1.82) | 1.32 | (1.03–1.69) |

| Never | 23.90% | 1.44 | (1.23–1.68) | 1.34 | (1.11–1.62) | 1.48 | (1.17–1.87) | 1.70 | (1.31–2.20) | 1.45 | (1.10–1.93) |

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||||||||||

| Age, per 10 year increase | 0.61 | (0.55–0.66) | 0.73 | (0.66–0.81) | 1.31 | (1.17–1.47) | 1.30 | (1.13–1.49) | 1.50 | (1.28–1.75) | |

| Race | |||||||||||

| White (Non-Hisp.), Hispanic, Other | 15.40% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| African American (Non-Hispanic) Site | 17.60% | 1.44 | (1.0–1.9) | 1.36 | (0.98–1.88) | 1.48 | (1.01–2.15) | 1.68 | (1.08–2.61) | 1.37 | (0.90–2.01) |

| Chicago, IL | 18.80% | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Bronx, NY | 15.40% | 0.56 | (0.33–0.96) | 0.69 | (0.41–1.15) | 1.74 | (0.88–3.42) | 1.86 | (0.91–3.81) | 3.28 | (1.66–6.51) |

| Brooklyn, NY | 13.70% | 0.30 | (0.17–0.53) | 0.43 | (0.25–0.72) | 0.97 | (0.47–2.02) | 1.23 | (0.58–2.62) | 2.77 | (1.33–5.75) |

| Washington, DC | 11.80% | 0.23 | (0.13–0.43) | 0.38 | (0.22–0.68) | 0.36 | (0.14–0.93) | 0.45 | (0.18–1.18) | 0.88 | (0.39–2.04) |

| Los Angeles, CA | 14.60% | 0.33 | (0.19–0.58) | 0.71 | (0.42–1.20) | 1.03 | (0.50–2.09) | 1.70 | (0.79–3.63) | 2.82 | (1.39–5.72) |

| San Francisco, CA | 27.10% | 2.64 | (1.52–4.58) | 3.06 | (1.80–5.20) | 5.26 | (2.68–10.3) | 5.48 | (2.70–11.13) | 3.51 | (1.80–6.77) |

Effect of ART adherence was calculated in a separate model including only ART users.

Risk factors for heavy (daily) marijuana use were different from predictors for any marijuana use. These differences were observed both when daily marijuana users were compared to all other women, and when daily marijuana users were compared to less frequent marijuana users only (Table 3). In contrast to the associations seen for any marijuana use, daily marijuana use was not associated with most other risk behaviors, and was associated with older instead of younger age. Daily marijuana use was also significant associated with higher current CD4 cell count, and improved quality of life (Table 3).

Factors associated with ART adherence in longitudinal analysis

In multivariate longitudinal analysis, current marijuana users were significantly less likely to be adherent to ART (aOR=0.60, 95%CI=0.50–0.71). These models were adjusted for time-updated measures of current CD4 cell count, age, depression, quality of life, body-mass index, tobacco use, number of recent sexual partners, as well as race/ethnicity and study site. In contrast, daily marijuana use was not significantly associated with ART adherence (aOR=0.85, 95%CI=0.65–1.09, p=0.22). Further, among marijuana users currently on ART, daily marijuana users had significantly increased ART adherence compared to more casual marijuana uses (aOR=1.37, 95%CI=1.03–1.83, p=0.03).

DISCUSSION

This cohort study evaluated marijuana use and related reasons for use every six months over 16 years in a large multi-site study of HIV-infected women in the United States. The study demonstrates that marijuana use is common among HIV-infected women in the U.S., including both recreational and medicinal marijuana use. While the prevalence of marijuana use decreased during study follow-up as participants aged, an increasing proportion of HIV-infected women using marijuana in the study also began using marijuana daily. These heavy users reported using marijuana primarily for medicinal purposes, suggesting the rationale for marijuana use among HIV-infected women in this HAART era study may have changed from purely recreational to a combination of recreational and medicinal usage.

The prevalence of current marijuana use in this multi-center cohort of HIV-infected women in the U.S. was similar to that reported in several other U.S. studies12, 29, although it was lower than a Canadian study which reported 43% of HIV-infected participants used marijuana recently.30 A previous study of marijuana use in this same WIHS cohort had a lower prevalence of current marijuana use than this study because they had excluded women with an history of daily marijuana use before study baseline.16 The increasing use of medical marijuana among HIV-infected women in this study is consistent with previous studies showing medicinal use in the majority of HIV-infected marijuana users.12, 29, 30 In the most recent data in this study, some medicinal marijuana use was reported by 55% of current marijuana users, similar to other U.S. studies which reported medical use in 45–67% of HIV-infected marijuana users.29, 30 Despite high rates of recreational marijuana use, current rates of medically-prescribed marijuana use remained uncommon overall, reported by 7.1% of HIV-infected women in 2010 in the current study; other studies reported a higher prevalence (10–29%) of current medicinal marijuana use among HIV-infected individuals 3, 11, 29–31, but this may in part be explained by our definition of medicinal marijuana use as being prescribed by a doctor. Many women who reporting using marijuana that was not medically prescribed, indicated relief of HIV-related symptoms or increasing appetite as a motivator for use (i.e. self prescribed medicinal usage).

There was substantial variation in marijuana use between the six U.S. study sites. These differences may reflect differing state laws and availability of any marijuana and medically prescribed marijuana. In California, which had the highest prevalence and increase in medicinal marijuana use during the study, medical marijuana became legal in 1996. Medicinal marijuana was not legalized in the other states in this study during the study period, although in D.C. medicinal marijuana did become legal in 2010. A recent study suggested that states with legal medical marijuana use have a higher prevalence of marijuana use, but that the percent of marijuana users with marijuana dependence/abuse was similar in states with and without laws allowing medical marijuana use.14 However variation in study recruitment strategies between sites may also contribute to the observed differences as some venue based recruitment may have targeted drug users at risk for HIV-infection.

Reported reasons for marijuana use were similar to previous studies, with stress reduction and appetite stimulation as the most commonly reported reasons for use.29, 30 While many women report using marijuana for social and relaxation reasons, marijuana use for symptom relief was also noted as an important motivator among these HIV-infected women. Reasons for marijuana use in this study were also consistent with previously reported studies showing appetite stimulation, reduction of pain, relaxation/social use, anxiety reduction, and help with sleep.4, 29, 30, 32 Research supports the utility of marijuana in reducing these symptoms with improvements in appetite, nausea, anxiety, depression, tingling, weight loss and tiredness reported from marijuana use in other observational studies of HIV-infected individuals3, 11, 30. If cannabanoids are proven to reduce these ART-related side effects, medicinal marijuana use may become an increasingly important option for HIV-infected individuals, where laws allow its use. Indeed, recent randomized placebo controlled trials of HIV-infected individuals demonstrated significant reduction in neuropathy-associated pain7, 8 and improved appetite33, 34 from smoked cannabis, supporting its utility. As more HIV-infected individuals initiate ART treatment early and remain on treatment for long periods, reduction of ART-associated morbidity is increasingly important.

Adherence to ART was lower among current marijuana users than non-users in this study, consistent with previous research.35 However, ART adherence was not reduced among the more consistent daily marijuana users. These results are similar to those observed by a previous study of 168 HIV-infected patients on ART in California who reported an increase in ART adherence among daily marijuana users despite decreased adherence among marijuana users overall.36 It appears that for some women, regular marijuana use reduces HIV associated symptoms, and does not impair adherence to ART. Multiple patterns of use are present in the cohort, ranging from highly adherent regular marijuana users, to higher risk women whose marijuana use may be associated with use of other drugs and higher risk sexual behaviors. The association of recent sexual behavior and drug use with recent marijuana use observed in this study has been shown in many other studies,37 as risk behaviors are often correlated. The fact that sex and drug use behavior were not associated with daily marijuana use in this study underscores the different nature of daily marijuana use and is consistent with the interpretation that some of daily marijuana use is medicinal rather than recreational.

There are several limitations and strengths to the current study. Validity of self-reported drug use has supported in multiple studies,38, 39 although some studies suggest risk behaviors are under-reported compared to use of computer-assisted self interview.22 Whether marijuana use was medicinal or recreational was only specifically asked in 2009 and therefore the trend in medicinal marijuana use could not be evaluated. However, earlier surveys did ask about other questions related to reasons for marijuana use and as the frequency of marijuana use was collected longitudinally the trends in daily marijuana use could be explored. Marijuana abuse/dependence was not assessed. In addition, this was an observation study so marijuana users were self selected (not assigned) and this study did not assess the efficacy or safety of marijuana use. Further, we analyzed changes in marijuana use at cohort level (not the changes within individuals), we can not rule out the possibility that immigrative or emmigrative selection bias might in part explain the changes in marijuana use observed in the cohort.

Our study demonstrates that marijuana use is common among a representative group of U.S. women living with HIV, and that daily marijuana use did not decrease ART adherence. Further, marijuana use was reported by many users to alleviate HIV-related symptoms. Given this pattern, which appears to be part of a broad trend towards use of marijuana in chronic illness, additional research is needed on the optimal formulation, efficacy, effectiveness and safety of this patient led treatment.

Acknowledgments

Support: Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington, DC, Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co-funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 R024131). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support includes:K23 DA025736 (NIDA; to S Nahvi).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren SA. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Oct 1;58(2):181–187. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d490a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pettersen JA, Jones G, Worthington C, et al. Sensory neuropathy in human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients: protease inhibitor-mediated neurotoxicity. Ann Neurol. 2006 May;59(5):816–824. doi: 10.1002/ana.20816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolridge E, Barton S, Samuel J, Osorio J, Dougherty A, Holdcroft A. Cannabis use in HIV for pain and other medical symptoms. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2005 Apr;29(4):358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belle-Isle L, Hathaway A. Barriers to access to medical cannabis for Canadians living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2007 Apr;19(4):500–506. doi: 10.1080/09540120701207833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catz SL, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL. Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2000 Mar;19(2):124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palella FJ, Jr., Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998 Mar 26;338(13):853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrams DI, Jay CA, Shade SB, et al. Cannabis in painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2007 Feb 13;68(7):515–521. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000253187.66183.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis RJ, Toperoff W, Vaida F, et al. Smoked medicinal cannabis for neuropathic pain in HIV: a randomized, crossover clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009 Feb;34(3):672–680. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seamon MJ, Fass JA, Maniscalco-Feichtl M, Abu-Shraie NA. Medical marijuana and the developing role of the pharmacist. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy : AJHP : Official Journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2007 May 15;64(10):1037–1044. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker JM, Huang SM, Strangman NM, Tsou K, Sanudo-Pena MC. Pain modulation by release of the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999 Oct 12;96(21):12198–12203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fairfield KM, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Libman H, Phillips RS. Patterns of use, expenditures, and perceived efficacy of complementary and alternative therapies in HIV-infected patients. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998 Nov 9;158(20):2257–2264. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.20.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pence BW, Thielman NM, Whetten K, Ostermann J, Kumar V, Mugavero MJ. Coping strategies and patterns of alcohol and drug use among HIV-infected patients in the United States Southeast. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008 Nov;22(11):869–877. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Strat Y, Le Foll B. Obesity and cannabis use: results from 2 representative national surveys. Am J Epidemiol. 2011 Oct 15;174(8):929–933. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cerda M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin D. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012 Jan 1;120(1–3):22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann DE, Weber E. Medical marijuana and the law. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Apr 22;362(16):1453–1457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo WH, Wilson TE, Weber KM, et al. Initiation of regular marijuana use among a cohort of women infected with or at risk for HIV in the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2004 Dec;18(12):702–713. doi: 10.1089/apc.2004.18.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology. 2005 Sep;12(9):1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hessol N, Weber KM, Holman S, et al. Retention and attendance of women enrolled in a large prospective study of HIV-1 in the United States. J Womens Health. 2009;18:1627–1637. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hessol NA, Schneider M, Greenblatt RM, et al. Retention of women enrolled in a prospective study of human immunodeficiency virus infection: impact of race, unstable housing, and use of human immunodeficiency virus therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Sep 15;154(6):563–573. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hjorthoj CR, Hjorthoj AR, Nordentoft M. Validity of Timeline Follow-Back for self-reported use of cannabis and other illicit substances--systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Behav. 2012 Mar;37(3):225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macalino GE, Celentano DD, Latkin C, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D. Risk behaviors by audio computer-assisted self-interviews among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative injection drug users. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002 Oct;14(5):367–378. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.6.367.24075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhhs. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation Panel on Clinical Practices for the Treatment of HIV infection. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tandon SD, Cluxton-Keller F, Leis J, Le HN, Perry DF. A comparison of three screening tools to identify perinatal depression among low-income African American women. Journal of affective disorders. 2012;136:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bozzette SA, Hays RD, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Wu AW. Derivation and properties of a brief health status assessment instrument for use in HIV disease. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995 Mar 1;8(3):253–265. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199503010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu C, Weber K, Robison E, Hu Z, Jacobson LP, Gange SJ. Assessing the effect of HAART on change in quality of life among HIV-infected women. AIDS Res Ther. 2006;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Genna NM, Cornelius MD, Cook RL. Marijuana use and sexually transmitted infections in young women who were teenage mothers. Women's health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health. 2007 Sep-Oct;17(5):300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woody GE, Donnell D, Seage GR, et al. Non-injection substance use correlates with risky sex among men having sex with men: data from HIVNET. Drug and alcohol dependence. 1999 Feb 1;53(3):197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prentiss D, Power R, Balmas G, Tzuang G, Israelski DM. Patterns of marijuana use among patients with HIV/AIDS followed in a public health care setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004 Jan 1;35(1):38–45. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furler MD, Einarson TR, Millson M, Walmsley S, Bendayan R. Medicinal and recreational marijuana use by patients infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2004 Apr;18(4):215–228. doi: 10.1089/108729104323038892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braitstein P, Kendall T, Chan K, et al. Mary-Jane and her patients: sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of HIV-positive individuals using medical marijuana and antiretroviral agents. Aids. 2001 Mar 9;15(4):532–533. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103090-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cinti S. Medical marijuana in HIV-positive patients: what do we know? J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2009 Nov-Dec;8(6):342–346. doi: 10.1177/1545109709351167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haney M, Gunderson EW, Rabkin J, et al. Dronabinol and marijuana in HIV-positive marijuana smokers. Caloric intake, mood, and sleep. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Aug 15;45(5):545–554. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31811ed205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riggs PK, Vaida F, Rossi SS, et al. A pilot study of the effects of cannabis on appetite hormones in HIV-infected adult men. Brain Res. 2012 Jan 11;1431:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gebo KA, Keruly J, Moore RD. Association of social stress, illicit drug use, and health beliefs with nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Feb;18(2):104–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.10801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Jong BC, Prentiss D, McFarland W, Machekano R, Israelski DM. Marijuana use and its association with adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons with moderate to severe nausea. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Jan 1;38(1):43–46. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200501010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith AM, Ferris JA, Simpson JM, Shelley J, Pitts MK, Richters J. Cannabis use and sexual health. J Sex Med. 2010 Feb;7(2 Pt 1):787–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denis C, Fatseas M, Beltran V, et al. Validity of the Self-Reported Drug Use Section of the Addiction Severity Index and Associated Factors Used under Naturalistic Conditions. Subst Use Misuse. Mar;47(4):356–363. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.640732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy DA, Durako S, Muenz LR, Wilson CM. Marijuana use among HIV-positive and high-risk adolescents: a comparison of self-report through audio computer-assisted self-administered interviewing and urinalysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2000 Nov 1;152(9):805–813. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.9.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]