Abstract

Commercially available Angiotensin II AT1 receptor antibodies are widely employed for receptor localization and quantification, but they have not been adequately validated. In this study, six commercially available AT1 receptor antibodies were characterized by established criteria: sc-1173 and sc-579 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., AAR-011 from Alomone Labs, Ltd., AB15552 from Millipore, and ab18801 and ab9391 from Abcam. The immunostaining patterns observed were different for every antibody tested, and were unrelated to the presence or absence of AT1 receptors. The antibodies detected a 43 kDa band in western blots, corresponding to the predicted size of the native AT1 receptor. However, identical bands were observed in wild-type mice and in AT1A knock-out mice not expressing the target protein. Moreover, immunoreactivity detected in rat hypothalamic 4B cells not expressing AT1 receptors or transfected with AT1A receptor construct was identical, as revealed by western blotting and immunocytochemistry in cultured 4B cells. Additional prominent immunoreactive bands above and below 43 kDa were observed by western blotting in extracts from tissues of AT1A knock-out and wild-type mice and in 4B cells with or without AT1 receptor expression. In all cases, the patterns of immunoreactivity were independent of the AT1 receptor expression and different for each antibody studied. We conclude that, in our experimental setup, none of the commercially available AT1 receptor antibodies tested met the criteria for specificity and that competitive radioligand binding remains the only reliable approach to study AT1 receptor physiology in the absence of full antibody characterization.

Keywords: GPCR receptor antibodies, Antibody characterization, Angiotensin II receptors, Renin–angiotensin System, AT1 receptor immunocytochemistry, AT1 receptor antibodies, AT1A receptor knock-out

Introduction

The renin–angiotensin system (RAS) is recognized as a fundamental regulatory system in peripheral organs and in the brain (Bader 2010; Paul et al. 2006; Saavedra et al. 2011). In particular, there is an increasing interest on its main active component, Angiotensin II (Ang II), and on its physiological AT1 receptor type (Mehta and Griendling 2007; Bader 2010; Paul et al. 2006; Saavedra et al. 2011),

Rodents express two AT1 receptor subtypes, the AT1A and AT1B receptors (Sasamura et al. 1992; Chiu et al. 1993). AT1A and AT1B receptors have very high coding region homology, and are pharmacologically and immunologically indistinguishable (Inagami et al. 1994; Kakar et al. 1992; Lenkei et al. 1999; Paxton et al. 1993). Thus, selective detection of AT1A and AT1B receptor protein or binding sites is not possible using immunohistochemistry or receptor binding analysis. Therefore, the findings obtained with the use of these techniques are expressed as AT1 receptors, the sum of expression of AT1A and AT1B receptors, without distinction of the subtype. The selective distribution and regulation of AT1A and AT1B receptors may only be performed by detecting receptor subtype mRNA. Since AT1A and AT1B receptors do not have significant homology in the non-coding regions, mRNA determinations are performed by in situ hybridization or real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) using riboprobes or selected primers targeted to the AT1A or AT1B 3′ non-coding regions (Lenkei et al. 1995; Jöhren et al. 1995; Jöhren and Saavedra 1996; Burson et al. 1994; Sánchez-Lemus et al. 2009).

AT1 receptor antibodies have been used in several thousand studies to determine receptor localization, quantification, immunoprecipitation, and other receptor characteristics (Table 1). For the most part, publications employed commercially available AT1 receptor antibodies. Unfortunately, anecdotic reports from many laboratories and our own experience reveal that the use of commercially available AT1 receptor antibodies results in variable, unpredictable, and above all, unreliable results.

Table 1.

PubMed publications on Angiotensin II and Angiotensin II AT1 receptors

| PubMed search, to March 2012 | Number of publications to March 2012 |

|---|---|

| Angiotensin II | 55,155 |

| Angiotensin II AT1 receptor antibodies | 3,360 |

| AT1 receptor immunocytochemistry | 394 |

| AT1 receptor western blotting | 338 |

| AT1 receptor immunoprecipitation | 53 |

| AT1 receptor flow cytometry | 18 |

To address this problem, in the present study six commercially available AT1 receptor antibodies were characterized according to established criteria.

The AT1A knock-out mice (Ito et al. 1995; Oliverio et al. 1997) was chosen for the study because the AT1A receptor is the principal AT1 receptor subtype in most rodent organs, including the liver, kidney cortex, and brain (Burson et al. 1994; Lenkei et al. 1995; Jöhren et al. 1995; Jöhren and Saavedra 1996; Häuser et al. 1998). Furthermore, knock-out of both AT1A and AT1B receptors produces multiple phenotypical and physiological abnormalities and is detrimental to survival (Oliverio et al. 1998). Immunological detection of AT1 receptors was compared in all cases with competitive receptor binding, using standard membrane binding and quantitative auto-radiography techniques (Tsutsumi and Saavedra 1991), and, when appropriate, with selective RT–PCR. Antibody specificity was tested in another model, the rat hypothalamic neuronal cell line 4B (Kasckow et al. 2003; Nikodemova et al. 2003; Liu et al. 2006) which in preliminary experiments was shown to lack AT1 receptors.

Availability of a mouse knock-out strain and a cell line devoid of target protein allowed the definitive determination of antibody specificity, a necessary condition to insure that results are replicable and likely to be correct (Saper and Sawchenko 2003; Saper 2005, 2009; Rhodes and Trimmer 2006; Lorincz and Nusser 2008; Michel et al. 2009).

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male wild-type C57BL6/J and AT1A knock-out B6.129P2-Agtr1atm1Unc/J mice without detectable functional protein (Ito et al. 1995) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, MA, USA) and kept five per cage with free access to water and a standard diet at 22 °C under a 12:12 h dark–light cycle. Aged animals (20–24 months) were used in the study. The mice were killed by cervical dislocation without prior anesthesia and their brains, kidneys, livers, and adrenal glands were immediately dissected, snap-frozen in isopentane on dry ice and stored at -80 °C until further processed. Eight weeks old male Wistar Hannover rats were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY, USA) and kept three per cage for 1 week, with free access to water and a standard diet at 22 °C under a 12:12 h dark–light cycle. The rats were killed by fast decapitation and their adrenal glands and kidneys immediately removed, and processed as above. The National Institute of Mental Health Animal Care and Use Committee (Bethesda, MD, USA) approved all procedures. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering (National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Publication No. 80-23, revised 1996).

Antibodies

Rabbit antibodies sc-1173 and sc-579 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); AB15552 from Millipore (Billierica, MA, USA); AAR-011 from Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel); and ab18801 from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Mouse antibody ab9391 was purchased from Abcam. The information on immunogen used, specificity and applications, as provided by the manufacturers, is listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of AT1 receptor antibodies used in the study

| Antibody | Immunogen | Specificity | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT1 (N-10), affinity purified rabbit pAb, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat # sc-1173 | Non-specified peptide from N-terminal extracellular domain of human AT1 receptor | H, M, R | WB, IF, IP, ELISA |

| AT1 (306), rabbit pAb, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat # sc-579 | Protein corresponding to amino acids 306–359 from C-terminus of human AT1 receptor | H, M, R | WB, IF, IP, ELISA |

| AT1, affinity purified rabbit pAb, Millipore, cat # AB15552 | Non-specified peptide from N-terminus of human AT1 receptor | H, M, R | WB, IHC, ICC, FC |

| AT1, affinity purified rabbit pAb, Alomone Labs, cat # AAR-011 | Peptide NSSTEDGIKRIQDDC corresponding to amino acids 4–18 from N-terminus of human AT1 receptor | H, M, R | WB, IHC, ICC, FC |

| AT1, affinity purified rabbit pAb, Abcam, cat # ab18801 | Peptide PSDNMSSSAKKPASC corresponding to amino acids 341–355 of rat AT1A receptor and peptide SSSAKKSASFFEVE corresponding to amino acids 346–359 of rat AT1B receptor | M, R | WB, IHC |

| [1E10–1A9] mouse mAb, Abcam, cat # ab9391 | Protein corresponding to amino acids 297–356 from C-terminus of human AT1 receptor | H, R | WB, IHC, ICC/IF, IP, ELISA |

pAb polyclonal antibody, mAb monoclonal antibody, H human, M mouse, R rat, WB western blot, IHC immunohistochemistry, ICC immunocytochemistry, IF immunofluorescence, IP immunoprecipitation, FC flow cytometry, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Constructs

The AT1A receptor construct, kindly provided by Dr. Kathryn Sandberg (Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA) is a 2.2 kb HindIII–NotI fragment of cDNA clone pCa18b initially provided by Dr. Ken Berstein (Cedars-Sinai Hospital, Los Angeles, CA, USA) (Murphy et al. 1991), cloned into pCDNA1. The clone contains the 5′ UTR, the full coding region and 3′ UTR until the first poly-A tail of rat smooth muscle AT1A receptor (Murphy et al. 1991). This construct was subcloned into a pcDNAI/Amp expression vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA).

A construct containing 676 bp of corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) 3′ UTR (bp 1,754–2,430), or an empty vector pcDNA3.1 were used as negative controls for the western blot and immunocytochemistry, respectively. The CRH 3′ UTR construct was generated by PCR from pCRHBgl II, provided by Dr A. Seasholtz (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), with HindIII and BamHI restriction sites at the ends (M. Nikodemova and G. Aguilera, unpublished) and cloned into pcDNA 3.1 expression vector (Invitrogen).

Cells and Transfection

Hypothalamic 4B cells (Kasckow et al. 2003), provided by Dr. John Kasckow (VA Pittsburgh Health Care System, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 10 % horse serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells were transfected with constructs mentioned above by electroporation using a Nucleofector (Lonza Walkersville, Inc., Walkersville, MD, USA) and Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V (Lonza). Aliquots of 3 million 4B cells were transfected with 5 μg of empty plasmid pcDNA3.1, or pcDNAI/Amp-CRH-3′ UTR as negative controls for the immunocytochemistry and western blots, respectively, or the AT1 expression vector pcDNAI/Amp-rAT1A. After transfection, cells were resuspended in DMEM containing 10 % horse serum and 10 % fetal bovine serum and plated into 12-well culture plates at a density of 300,000 cells/well for AT1 receptor binding assay and 3 × 106 cells per 100 mm plates for western blot. Experiments were performed 24 h after transfection.

Angiotensin II Receptor Autoradiography in Tissue Sections

Fresh-frozen brains and kidneys were cut to 16 μm thick coronal sections on a cryostat at -20 °C. The sections were thaw-mounted on gelatin-coated slides (Tekdon, Myakka City, FL, USA), dried for 5 min at 50 °C and stored at -80 °C until used. Before use, the sections on slides were dried in a desiccator at room temperature and then slightly fixed in 0.2 % formaldehyde (Mallinckrodt Chemicals, Philipsburg, NJ, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min and washed twice for 5 min in PBS. The receptor autoradiography was performed as described previously (Tsutsumi and Saavedra 1991). The sections were preincubated for 15 min at 22 °C in binding buffer containing 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.005 % bacitracin (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 5 mM Na2EDTA, 120 mM NaCl, and 0.2 % proteinase-free BSA (Sigma–Aldrich). Sections were then incubated for 2 h at 22 °C in fresh binding buffer in the presence of 0.25 nM [125I] Sar1–Ile8–Ang II (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA) to visualize total Ang II binding to AT1 and AT2 receptors. To determine AT1 receptor-specific binding, consecutive sections were incubated as above in the presence of 10 μM of the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan (DuPont-Merck, Wilmington, DE, USA). Slides were washed four times for 1 min in Tris–HCl, pH 7.4 at 4 °C, followed by a 30 s rinse in distilled water at 4 °C. Slides were then dried under a stream of cold air and exposed to Biomax MR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA).

Angiotensin II Receptor Binding Assay in 4B Cells

Hypothalamic non-transfected 4B cells, 4B cells transfected with the AT1A receptor, and 4B cells transfected with the CRH construct were plated onto 12-well plates at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well and used for binding assay 24 h later. The cells were washed twice in PBS and then preincubated for 15 min at 22 °C in a 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.005 % bacitracin (Sigma–Aldrich), 5 mM EDTA, 120 mM NaCl, and 0.2 % protease-free BSA (Sigma–Aldrich). After preincubation the buffer was discarded and the cells were incubated for 2 h in fresh buffer containing 0.05 nM [125I]Sar1–Ang II (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA) to reveal total Ang II receptor binding. To determine expression of Ang II AT1 receptors, the cells were incubated as above in the presence of 10 μM losartan (DuPont Merck), a selective AT1 receptor antagonist, or 5 μM non-labeled Ang II (Bachem, Torrance, CA, USA) to assess non-specific binding. The incubation was performed at 4 °C to rule out the possible effect of the internalization of receptor–ligand complex. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with PBS, lysed in 0.5 M NaOH for 60 min, and the lysates were counted in a γ-counter.

Western Blot

Hypothalamus, liver and kidney cortex from wild-type and AT1A knock-out mice were homogenized 1:10 wt:vol in ice–cold RIPA buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 % NP-40, 0.1 % SDS, 0.5 % sodium deoxycholate; supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indiana, IN) and centrifuged at 14,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration in the supernatant was determined by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Hypothalamic 4B cells were lysed in RIPA buffer as above.

The protein extracts were separated by SDS–PAGE using NuPAGE Bis–Tris gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked in casein-based blocking buffer (Sigma–Aldrich) for 60 min at room temperature and exposed to primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Primary AT1 receptor antibodies are listed in Table 2. The antibody dilutions were as follows (antibodies are listed according to their catalog numbers): sc-1173, 1:1,000; sc-579, 1:1,000, AB15552, 1:500; AAR-011, 1:500; ab18801, 1:1,000, as recommended by the manufacturers. The minimum exposure time to detect signals at the predicted 43 kDa size of the native AT1 receptor was selected. After incubation, the membranes were washed and exposed to secondary horse–radish peroxidase–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK, catalog number NA934V, 1:5,000) for 2 h at room temperature and then exposed to SuperSignal West Dura Substrate (Thermo Scientific) for chemiluminescent detection. After AT1 receptor detection, the membranes were stripped for 15 min at room temperature in restore western blot stripping buffer (Thermo Scientific cat # 21059), blocked, exposed to β-Actin antibody (1:10,000, Sigma–Aldrich cat # A5441) and chemiluminescence was detected as above.

Immunocytochemistry

Non-transfected hypothalamic 4B cells were plated into 4-well slide chambers (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) pre-coated with 0.1 mg/ml poly-l-lysine. Twenty-four hours after plating, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed with ice–cold 100 % methanol for 15 min, permeabilized for 10 min with 0.2 % Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked for 60 min with PBS containing 1 % bovine serum albumin, 0.05 % Triton-X-100 and 10 % normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated with cells overnight at 4 °C. Antibodies sc-1173, sc-579, and AB15552 were used in 1:100 dilutions; antibody ab9391 was diluted 1:50. All dilutions were in the range recommended by the manufacturers.

In a separate experiment, hypothalamic 4B cells transfected with the empty vector pcDNA3.1 or the AT1A receptor pcDNAI/Amp–rAT1A vector were plated as above and cultured for 24 h before processing for immunocytochemistry as described above. The cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with sc-1173, sc-579 or AB15552 antibodies diluted 1:100 or ab9391 or AAR-011 antibody diluted 1:50. The antibodies AAR-011 and AB15552 were provided with samples of immunizing peptide by the manufacturers. For these antibodies, preabsorption with the respective immunizing peptide was performed for 60 min at room temperature, with a 1:1 concentration of antibody:immunizing peptide before incubation with the primary antibodies.

After incubation with the primary antibodies, the cells were washed with PBS containing 0.1 % Tween 20 (PBS-T) and exposed to secondary fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Donkey FITC-conjugated IgG (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, cat # 711-095-152) or horse FITC-conjugated IgG (1:200, Vector Laboratories, cat # FI-2000) secondary antibodies were used to detect rabbit or mouse primary antibodies, respectively. After washing with PBS-T, the cells were mounted with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-containing mounting medium (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories) and images were acquired using a Axioskop fluorescent microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) connected to Zeiss Axiocam digital camera using 20 s exposure time for FITC fluorescence and 250 ms for 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) fluorescence. Images were processed using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) for contrast and brightness adjustment. Negative controls prepared by omission of primary antibodies did not show any FITC fluorescence under the above conditions.

RT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated from mouse kidney, liver, and adrenal gland and from 4B cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), followed by purification with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) was performed using 1 μg of total RNA and Super-Script III first-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT–PCR (Invitrogen). RT–PCR was performed in a 20 μl reaction mixture consisting of 10 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), 4 μl cDNA and 0.3 μM of each primer for a specific target on a DNA Engine OpticonTM (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The primers used are listed in Table 3. Amplification was performed at 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 20 s and 60 °C for 60 s. Serial dilutions of rat adrenal and mouse kidney or adrenal gland cDNA were used to obtain a standard curves.

Table 3.

List of PCR primers used in the study

| Gene | Species | Accession no. | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1A | Mouse | NM_177322 | GCTGGCAGGCACAGTTACAT | GACACTGGCCACAGTCTTCA |

| AT1B | Mouse | NM_175086 | TTTTCCCCAGAGCAAAGCTA | CCCTCCCCCAAATCAATAGT |

| 18S rRNA | Mouse | NR_0032783 | TTGACGGAAGGGCACCACCAG | GCACCACCACCCACGGAATCG |

| AT1A | Rat | NM_0309854 | AGCCTGCGTCTTGTTTTGAG | GCTGCCCTGGCTTCTGTC |

| AT1b | Rat | NMJB10092 | CACCTCGCCAAGGGAGAC | CACTTGCAGGCT TTGAACC |

| 18S rRNA | Rat | NR_0462371 | GACCATAAACGATGCCGACT | GTGAGGTTTCCCGTGTTGAG |

AT1A Angiotensin II receptor type 1A, AT1B Angiotensin II receptor type 1B, 18S rRNA 18S ribosomal RNA

Results

Angiotensin II Receptor mRNA Expression and AT1 Receptor Binding in Wild-Type and AT1A Knockout Mice

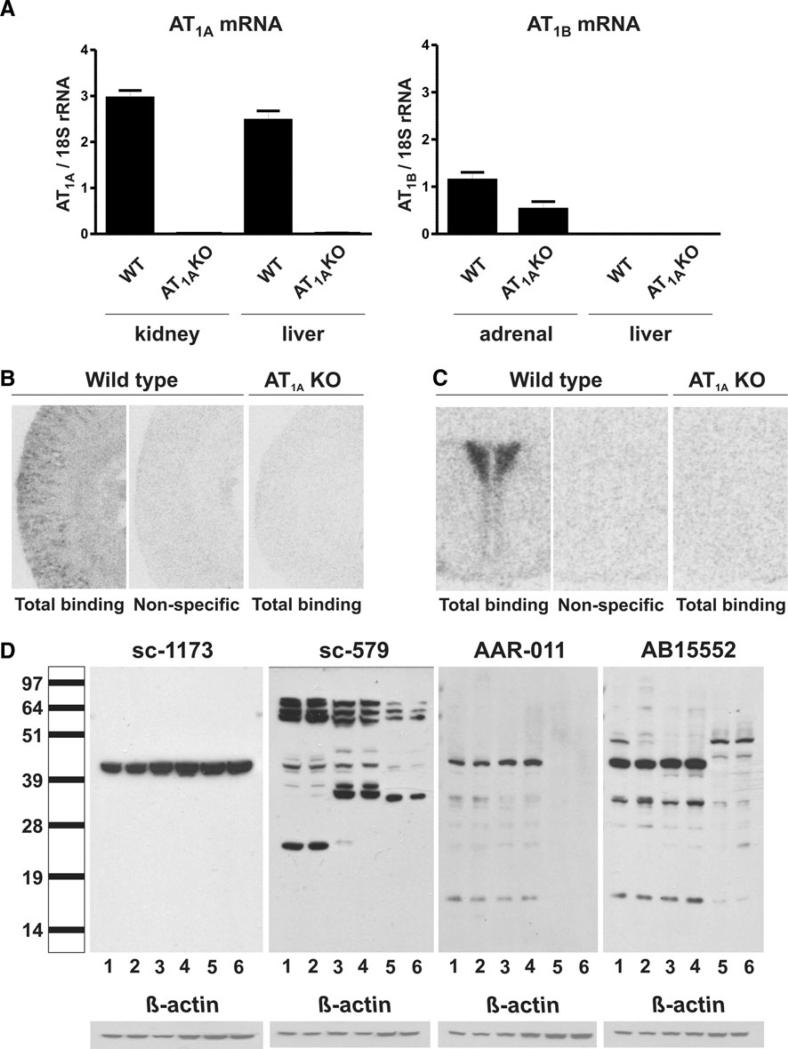

AT1A mRNA was clearly expressed in the kidney cortex and liver of wild-type mice and was absent from kidney cortex and liver of AT1A knockout mice (Fig. 1a). AT1B mRNA was expressed in the adrenal gland of both wild-type and AT1A knockout mice, and was absent from the liver of wild-type and knockout mice (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Angiotensin II AT1A receptor mRNA, AT1 receptor binding and protein in wild-type, and AT1A knock-out mice (a): expression of mRNAs was studied by RT–PCR in kidney cortex, liver, and adrenal gland of wild-type and AT1A knock-out mice. Gene expression was normalized to the level of 18S rRNA, and represents the mean ± SEM. of three individual determinations. Note that AT1A mRNA is not expressed in kidney cortex and liver of AT1A knock-out mice. AT1B mRNA is not expressed in liver of wild-type or knock-out mice, but it is expressed in adrenal gland of both wild-type and AT1A knock-out mice (b, c): AT1 receptor expression was studied by quantitative autoradiography in sections from kidney cortex (b) and from the hypothalamus (c) containing the PVN (–0.7 mm from bregma), incubated in the presence of 0.25 nM [125I] Sar1–Ile8–angiotensin II as described in “Materials and Methods”. Figures represent a typical result repeated in three different AT1A knock-out and wild-type mice. Note abundant receptor binding in the kidney cortex, predominantly localized to kidney glomeruli, and in the PVN of wild-type mice, completely displaced by incubation with the AT1 receptor-specific antagonist losartan (non-specific binding) and the complete absence of binding in the kidney cortex and PVN of AT1A knockout mice (d): Ang II AT1 receptor protein expression was studied by western blotting. Protein extracts were separated by SDS–PAGE electrophoresis and exposed to four different rabbit polyclonal anti-AT1 receptor antibodies as indicated by catalog number at the top of the picture. Lane 1 liver-WT, 2 liver-AT1AKO, 3 kidney cortex-WT, 4 kidney cortex-AT1AKO, 5 hypothalamus-WT, 6 hypothalamus-AT1AKO. The scale on the left indicates the size in kDa according to the positions of the protein ladder. The expected size of the AT1 receptor is about 43 kDa. Note that in all cases there is no difference between band intensity obtained from tissues from AT1A knock-out and wild-type mice and the presence of many bands not corresponding to the appropriate native AT1 receptor molecular size (43 kDa) with the use of antibodies sc-579, AAR-011, and AB15552. The figure represents a typical experiment repeated two times in individual samples

Wild-type mice expressed Ang II receptor binding in the kidney cortex, predominantly localized to glomeruli, and in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) (Fig. 1b, c). This binding was completely displaced by the specific AT1 receptor antagonist losartan (Fig. 1b, c). Conversely, Ang II receptor binding was absent in the kidney cortex and PVN of AT1A receptor knockout mice (Fig. 1b, c). The optical densities obtained from tissues of AT1A receptor knock-out mice were not different from non-specific binding in wild-type mice (Fig. 1b, c).

AT1 Receptor Protein Expression in Liver, Kidney Cortex, and Hypothalamus of Wild-Type and AT1A Knockout Mice

The AT1 receptor antibodies sc-1173, sc-579, AAR-011, and AB15552 were tested by western blot using protein extracts from liver, kidney cortex, and hypothalamus of wild-type and AT1A receptor knock-out mice. The pattern and the intensity of the immunoreactivity detected by each antibody were very different (Fig. 1d). All tested antibodies revealed bands of approximately 43 kDa corresponding to the expected size of the native non-glycosylated AT1 receptor protein. However, in all cases the 43 kDa bands were identical when protein extracts from tissues of wild-type or AT1A receptor knock-out mice were compared, indicating that the location and intensity of the bands detected were similar whether the target protein was present or not (Fig. 1d). Moreover, the pattern and the intensity of the bands varied with each antibody and each tissue, whether from wild-type or AT1A knockout mice (Fig. 1d).

Antibody sc-1173 detected a single band at about 43 kDa in all tissues examined (Fig. 1d). This band was in all cases identical when tissues from wild-type or AT1A knockout mice were compared (Fig. 1d). The 43 kDa band appeared to be more prominent in kidney cortex and hypothalamic extracts when compared to liver extracts (Fig. 1d).

Antibody sc-579 recognized the 43 kDa band, prominent in liver and kidney cortex extracts and of much lower intensity in hypothalamic extracts (Fig. 1d). In all cases, there was no difference in the intensity of the 43 kDa band when tissues from wild-type and AT1A receptor knockout mice were compared. In addition, antibody sc-597 recognized a number of higher and lower molecular size proteins with intensities higher than the 43 kDa band (Fig. 1d). The pattern of immunoreactivity of these additional bands varied with the tissue examined, and in all cases, there was no difference when tissues from wild-type and AT1A knockout mice were examined (Fig. 1d).

Antibodies AAR-011 and AB15552 recognized a dominant 43 kDa band in extracts from liver and kidney cortex, but not from hypothalamic extracts (Fig. 1d). There were additional bands above and below 43 kDa (Fig. 1d). The patterns of immunoreactivity varied with the tissue examined, and in all cases there was no difference in any of the bands detected when tissue extracts from wild-type and AT1A receptor knockout were compared (Fig. 1d).

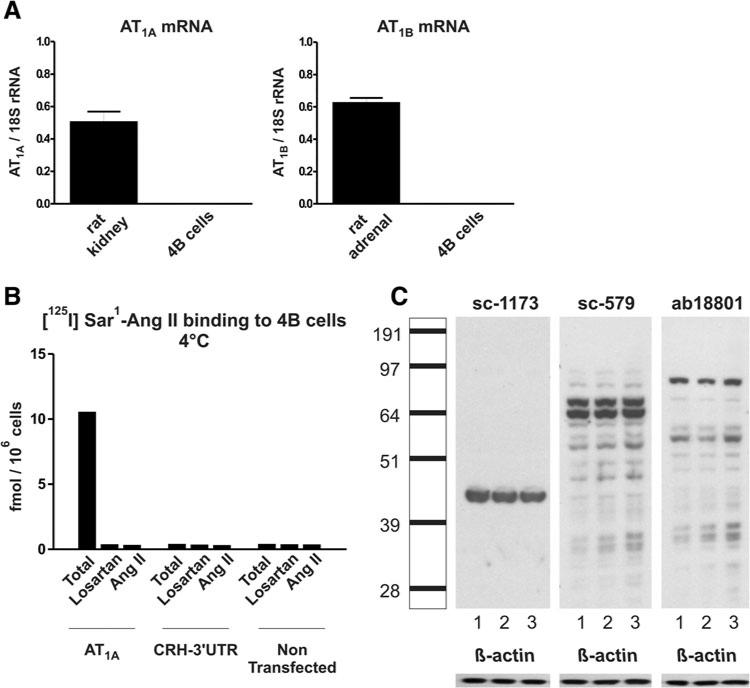

AT1 Receptor mRNA and AT1 Receptor Binding in Rat 4B Cells

AT1A and AT1B receptor mRNAs were clearly detected in rat kidney cortex and adrenal gland, respectively (Fig. 2a). Conversely, non-transfected rat hypothalamic 4B cells did not express detectable levels of either AT1A or AT1B receptor mRNA (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Angiotensin II receptor binding and western blot in control and AT1 receptor-transfected 4B cells (a): expression of AT1A and AT1B mRNA in naïve rat 4B cells. Gene expression was normalized to the level of 18S rRNA and represents the mean ± SEM of three individual determinations. Note that AT1A and AT1B receptor mRNAs were not expressed in rat 4B cells. For comparison, AT1A and AT1B mRNA were quantified in rat kidney and adrenal gland, respectively (b): binding of AT1 receptor- ligand [125I] Sar1–Ang II–AT1A in receptor transfected and control 4B cells. Hypothalamic 4B cells were transiently transfected with a vector containing the entire coding sequence of rat AT1A receptor. Cells transfected with a vector containing the sequence of rat CRH-3′ UTR and non-transfected cells were used as negative controls. The selective AT1 receptor antagonist losartan was used to displace the AT1 receptor-specific binding. Displacement with Ang II was used to determine the non-specific binding. Results are expressed in fmol per 106 cells. Notice the significant AT1 binding expression in AT1A receptor-transfected 4B cells, and the absence of binding in cells transfected with rat CRH-3′ UTR and in non-transfected cells (c): Western blot of protein extracts from AT1A receptor-transfected, CRH-3′ UTR-transfected and nontransfected 4B cells. Protein extracts were separated by SDS–PAGE and exposed to three rabbit polyclonal antibodies against AT1 receptor as indicated by catalog number at the top of the picture. Lane 1 AT1A receptor-transfected 4B cells, 2 CRH-3′ UTR-transfected 4B cells, 3 non-transfected 4B cells. The scale on the left indicates the size in kDa according to the positions of the protein ladder. The expected size of the AT1 receptor is about 43 kDa. Note that AT1 receptor binding is not expressed in control, non-transfected 4B cells, and or in 4B cells transfected with control rat CRH–3′ UTR. Conversely, significant AT1 receptor binding can be detected when 4B cells are transfected with AT1A receptors. Notice that there is no correlation between results obtained by receptor binding and by western blot

There was no [125I]–Sar1–Ang II binding in non-transfected 4B cells or in 4B cells transfected with rat CRH-3′ UTR (Fig. 2b). Conversely, prominent Sar1–Ang II binding was found in 4B cells transfected with the rat AT1A receptor construct (Fig. 2b). In these cells, binding was AT1 receptor-specific, since it was totally and equally displaced by the selective AT1 receptor antagonist losartan and by Ang II (Fig. 2b).

AT1 Receptor Protein Expression in Rat 4B Cells

The AT1 receptor antibodies sc-1173, sc-579, and ab18801 were tested by western blot using protein extracts from either non-transfected rat 4B cells, 4B cells transfected with the non-specific vector expressing rat CRH-3′ UTR, or 4B cells transfected with the rat AT1A receptor construct (Fig. 2c).

All polyclonal antibodies tested detected positive immunoreactivity in non-transfected and transfected 4B cells as determined by western blots, and the pattern of immunoreactivity differed markedly between the antibodies tested (Fig. 2c). In all cases, there was no difference in immunoreactivity when protein extracts from non-transfected, CRH-3′ UTR-transfected or AT1A receptor transfected 4B cell extracts were compared, indicating that the location and intensity of the bands detected were similar whether the target protein was present or not (Fig. 2c). Thus, the pattern of immunoreactivity depended on the antibody and not in the presence of AT1 receptors.

Antibody sc-1173 revealed a single band at approximately 43 kDa, with no differences between the bands corresponding to the AT1A receptor transfected, CRH-3′ UTR-transfected, or non-transfected cells (Fig. 2c).

Antibody sc-579 revealed a very different pattern of immunoreactivity, and the 43 kDa band was barely detectable (Fig. 2c). Instead, there were several prominent bands with molecular sizes above and below 43 kDa (Fig. 2c). Bands were similar for AT1A-transfected, CRH-3′ UTR-transfected, or non-transfected cells (Fig. 2c).

Antibody ab18801 revealed another different pattern. The 43 kDa band was not detectable; instead, there were several major bands located above and below 43 kDa. Again, there was no difference between bands from AT1A-transfected, CRH-3′ UTR-transfected and non-transfected cells (Fig. 2c).

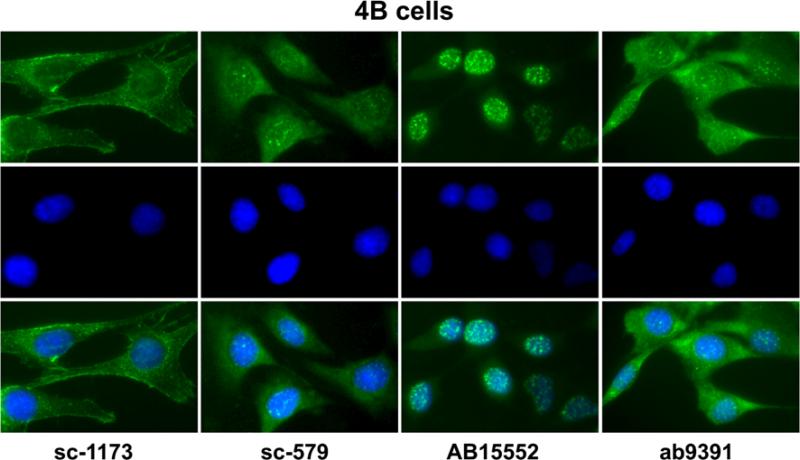

Immunoreactivity to AT1 Receptor Protein in Control, Non-transfected 4B Cells

Antibodies sc-1173, sc-579, AB15552, and ab9391 were tested for immunocytochemistry in non-transfected, control hypothalamic 4B cells devoid of AT1 receptors. All antibodies generated positive fluorescence signals, and the staining patterns differed among the antibodies tested (Fig. 3). Antibody sc-1173 stained predominantly membranes and possibly cytoskeleton (Fig. 3). Staining was mostly restricted to the perinuclear area for antibody sc-579, and there was no staining associated with the cell membrane (Fig. 3). Antibody AB15552 stained most intensely the cell nuclei (Fig. 3). Antibody ab9391 stained predominantly the cytoplasm with weaker staining in the nuclei (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescent staining with AT1 receptor antibodies in non-transfected hypothalamic 4B cells. The cells were stained with sc-1173, sc-579, AB15552, and ab9391 antibodies as described under “Materials and Methods”. Top row staining with AT1 receptor antibodies, middle row nuclear DAPI staining, bottom row merged images. Note that all antibodies reveal significant immunocytochemical staining, and that the staining pattern differs from each of the antibodies studied. Magnification is ×40

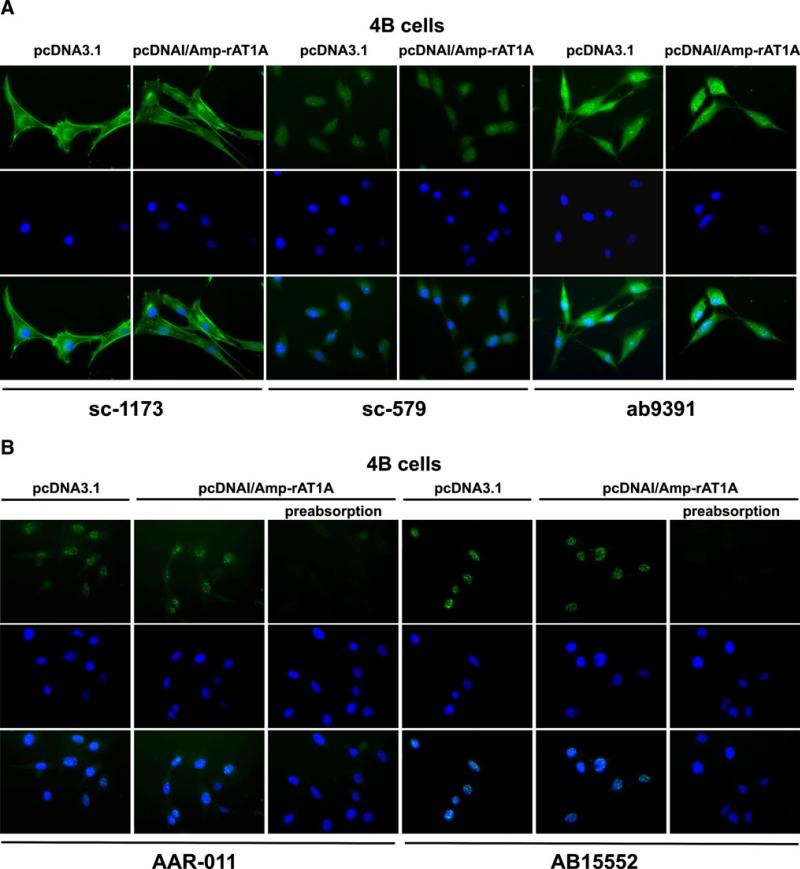

Immunoreactivity to AT1 Receptor Protein in 4B Cells Transfected with the AT1A Receptor Construct

Antibodies sc-1173, sc-579, and ab9391 were tested for immunocytochemistry in control 4B cells transfected with the empty vector and in 4B cells transfected with the AT1A receptor construct (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescent staining with AT1 receptor antibodies in AT1A-transfected hypothalamic 4B cells. a Cells transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3.1) or with rat AT1A receptor (pcDNAI/Amp–rAT1A), and stained with sc-1173, sc-579, and ab9391. Top row antibody staining, middle row: nuclear DAPI staining, bottom row merged images. Note that cells transfected with empty vector express immunoreactivity indistinguishable from that revealed by AT1A receptor transfection. b Cells transfected with empty vector or with AT1A receptors, and stained with AAR-011 or AT15552 antibodies, with or without preabsorption with immunizing peptide. Top row antibody staining, middle row nuclear DAPI staining, bottom row merged images. Note that preabsorption with the immunizing peptide eliminated antibody staining. Magnification is ×40

Every antibody tested revealed a different pattern of immunoreactivity (Fig. 4a), but for all antibodies tested, immunostaining patterns were identical in 4B cells transfected with the empty vector or with the AT1A receptor construct (Fig. 4a).

Antibody sc-1173 stained predominantly cell membranes and intracellular structures (Fig. 4a). Antibody sc-579 stained the perinuclear area and the cell nucleus with no staining associated with the cell membrane (Fig. 4a). Antibody ab9391 stained the perinuclear area and the nucleus, and no staining was visualized in the cell membrane (Fig. 4a).

Antibodies AAR-011 and AB15552 were tested in control 4B cells transfected with the empty vector and in 4B cells transfected with the AT1A receptor construct, with or without previous preabsorption with the corresponding antigens as provided by the manufacturers (Fig. 4b). Both the AAR-011 and the AB15552 antibodies stained the cell nucleus and no staining was associated with the cell membrane (Fig. 4b). Preabsorption with the corresponding antigens completely eliminated the immunocytochemical staining of both the AAR-001 and the AB15552 antibodies (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

This study clearly shows that all commercially available AT1 receptor antibodies tested recognize similar size proteins irrespective of whether AT1 receptors are expressed in the tissue or cell line. The present finding that each antibody yields identical immunostaining patterns in western blots of protein extracts from wild-type and AT1A receptor knockout mice demonstrates that these antibodies are not specific and their use may generate erroneous results.

A number of antibodies, most of them commercially available, have been long used for studying the function and regulation of AT1 receptors (Table 1). However, attempts of using some of these antibodies in our laboratory invariably revealed a lack of specificity. This personal experience in conjunction with several anecdotic reports from other laboratories prompted us to attempt to fully characterize a number of these commercially available antibodies.

The goal of the study was to determine whether or not commercially available AT1 receptor antibodies (Table 2) were specific, and consequently, whether results obtained with their use may generate reliable results. To this effect, several characterization criteria, as established earlier (Saper and Sawchenko 2003; Saper 2005, 2009) were applied to six commercially available AT1 receptor antibodies, as follows:

The precise antigen sequence should be provided.

This criterion was met for most of the antibodies with exception of sc-1173 from Santa Cruz and AB15552 from Millipore, for which the vendors specified the target receptor domain but did not provide the exact sequence of the immunizing peptide.

-

2

The antibodies must detect, in western blots from tissues expressing AT1 receptors, single bands of appropriate molecular weight or additional bands, again of appropriate molecular weight, if the antigen has several known molecular configurations. The band intensity should correlate with the degree of receptor expression.

It was anticipated that the antibodies would detect a band at approximately 43 kDa, the expected size of the native non-glycosylated AT1 receptor (Murphy et al. 1991). In western blots of mouse liver and kidney cortex extracts, all antibodies tested recognized a band at the approximate size of 43 kDa. The intensity of the 43 kDa band obtained in western blots from hypothalamic extracts depended on the antibody used and did not correlate with the expected AT1 receptor expression in this tissue when compared to that of the kidney or liver (Burson et al. 1994). For example, while the intensity of the 43 kDa band detected by antibody sc-1173 was similar to those obtained from liver and kidney cortex extracts, antibody AAR-011 did not give any signal at 43 kDa for hypothalamic extracts. Moreover, several antibodies detected clearly visible and sometimes predominant bands at molecular sizes higher and lower than 43 kDa, indicating the presence of major additional targets.

In AT1A knockout mice, the AT1A receptor was disrupted by insertion of a neomycin resistance cassette resulting in deletion of 0.5 kb of the coding region (Ito et al. 1995). As a consequence, out of a total of 359 amino acids in the AT1A receptor protein (Murphy et al. 1991), 177 (amino acids 13–189) were eliminated (Ito et al. 1995). Therefore, it is possible that non-functional fragments of the protein potentially expressed may interact with some of the antibodies. However, if this was the case the immunoreactive fragments would show molecular sizes different from the wild-type AT1A receptor. Instead, each of the antibodies tested yielded absolutely identical bands when the receptor is present, as in the wild-type mice, whether a major part is deleted or truncated, as in the knockout mice, or when the AT1A gene is not present, as in the non-translated 4B cells. This indicates that bands observed in knockout mice do not reflect AT1A receptor protein fragments but non-specific bands, some of them of a molecular size similar to that of the AT1A receptor.

The use of selective AT1A knock-out mice leads to the possibility of a compensatory increase in AT1B receptors (Oliverio et al. 1997; Ruan et al. 1999; Zhou et al. 2003) which may be immunochemically detected by the antibodies tested. However, our study did not detect AT1 receptor binding in kidney cortex or in the PVN of AT1A knockout mice. In addition, no AT1B mRNA was detectable in the liver of wild-type or AT1A knockout mice, confirming previous observations (Burson et al. 1994). This indicates that, at least in the tissues studied, AT1B receptors were not present in significant amounts.

-

3

Antibodies should not be reactive to tissues or cells not expressing the target protein, a fundamental condition to insure specificity. Antibody immunoreactivity should correlate with receptor expression as detected by additional methods such as competitive binding or RT–PCR.

Availability of a receptor knockout strain and of a cell line devoid of AT1 receptors allowed testing this essential condition. Antibody specificity was first tested in protein extracts of tissues from AT1A knockout mice. The AT1A knockout mice model (Ito et al. 1995; Oliverio et al. 1997) was chosen for the study because the AT1A receptor is the principal AT1 receptor subtype in most rodent organs, including the liver, kidney cortex, and brain (Burson et al. 1994; Lenkei et al. 1995; Jöhren et al. 1995; Jöhren and Saavedra 1996; Häuser et al. 1998). Mouse liver and hypothalamus only express AT1A receptor mRNA (Burson et al. 1994; Gasc et al. 1994), and kidney cortex express mainly AT1A receptor mRNA (Gasc et al. 1994). To determine specific AT1A receptor mRNA expression by RT–PCR, a primer targeted to the deleted domain of the AT1A receptor coding region was used. Initial experiments confirmed that AT1A knockout mice did not express AT1A mRNA in kidney cortex and liver or AT1 receptor binding in the kidney cortex and PVN.

Surprisingly, in all tissues studied, all antibodies tested detected identical bands at 43 kDa, whether or not the tissues were from wild-type mice or from AT1A receptor knockout mice not expressing the target protein. The identical immunoreactivity demonstrated in tissues from wild-type and AT1A knockout mice demonstrated that the AT1 receptor is not a major target for antibodies tested.

Antibody specificity was also tested in another model, the rat hypothalamic neuronal cell line 4B (Kasckow et al. 2003; Nikodemova et al. 2003; Liu et al. 2006) which does not express AT1A or AT1B receptor mRNA or AT1 binding, indicating the absence of target protein. Identical patterns of immunoreactivity were found by western blotting in non-transfected 4B cells (not expressing AT1 receptors), 4B cells transfected with a non-specific expression vector (pcDNA3.1–CRH 3′ UTR) or 4B cells transfected with AT1A receptor. These findings, and their lack of correlation with AT1 receptor binding, are consistent with the data in AT1A receptor knockout mice. In addition, antibody spec-ificity was tested by comparing immunocytochemical staining in cultured control non-transfected 4B cells, in 4B cells transfected with an empty vector, and in 4B cells transfected with an AT1A receptor construct. All antibodies tested revealed intense immunocytochemical staining in 4B cells, of identical distribution and intensity in control 4B cells not expressing AT1A receptors and in cells transfected with the AT1A receptor construct. The identical immuno-reactivity patterns observed in these experiments, irrespective of the presence of the AT1 receptor, indicate that all antibodies tested failed the most important criteria for specificity.

-

4

Antibodies raised against different antigen domains must reveal similar patterns of immunoreactivity.

In addition of recognizing identical bands in the presence or absence of the receptor, the pattern of the bands in the western blots was different for each antibody. Thus, the fact that antibodies directed against amino terminus or carboxy terminus, or even two antibodies against the same epitope of the receptor, recognized different molecular size bands, is clearly indicative that each antibody recognized different proteins present in both wild-type and AT1A knockout mice. The immunocytochemistry results in 4B cells, with each antibody tested revealing different staining patterns, but in all cases identical in cells expressing or not the receptor, are fully consistent with the western blot data. Therefore, in all cases the results depended on the antibody and not on the presence of AT1 receptors. The demonstration of additional bands, in many cases of higher intensity than the 43 kDa band, and of intense immunocytochemistry in 4B cells devoid of AT1 receptors, further established that most of the antibodies studied preferentially recognized off-target proteins distinct from the AT1 receptor. Although differences in glycosylation or receptor dimmerization could explain the presence of multiple bands in the western blot, the high variability on the ability of the different antibodies to recognize these bands is in support of lack of specificity.

Blockade of immunoreactivity following preabsorption of the antibodies with the antigen peptide is a test usually employed to validate antibody specificity. However, the present data raises questions about the validity of this test. Indeed, when some antibodies were preabsorbed with available target peptides, the immunoreactivity was abolished. This contrasts with the clear lack of specificity demonstrated by all other stringent tests of validity employed. This clearly indicates that the preabsorption test, indicating that the antibodies can bind to the purified or recombinant target protein, is not sufficient evidence to claim specificity (Saper and Sawchenko 2003; Saper 2005, 2007).

In keeping with the present observations, a recent publication reported the lack of specificity of commercially available and newly developed non-commercial AT1A receptor antibodies (Rateri et al. 2011). Moreover, previous reports questioned the specificity of a large number of G-protein-coupled receptor antibodies, including muscarinic, adrenergic, galanin, and dopamine receptors (Jositsch et al. 2009; Jensen et al. 2009; Bodei et al. 2009; Hamdani and van der Velden 2009; Lu and Bartfai 2009; Michel et al. 2009; Pradidarcheep et al. 2009).

In conclusion, none of the commercially available AT1 receptor antibodies tested here were specific for the AT1 receptor in western blot or immunocytochemical studies in rodents. Availability of AT1A and AT1B receptor knockout mice, cell lines devoid of AT1 receptors, and successful techniques for receptor transfection makes it possible to submit all additional available AT1 receptor antibodies to strict characterization criteria. This study demonstrates the need to strictly characterize any AT1 receptor antibody to be used in every particular experiment.

Contributor Information

Julius Benicky, Section on Pharmacology, DIRP, NIMH, NIH, 10 Center Drive, Bldg., 10, Room 2D-57, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Roman Hafko, Section on Pharmacology, DIRP, NIMH, NIH, 10 Center Drive, Bldg., 10, Room 2D-57, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Enrique Sanchez-Lemus, Section on Pharmacology, DIRP, NIMH, NIH, 10 Center Drive, Bldg., 10, Room 2D-57, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Greti Aguilera, Section on Endocrine Physiology, PDEGEN, NICHD, NIH, CRC, Room 1E-3330, 10 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Juan M. Saavedra, Section on Pharmacology, DIRP, NIMH, NIH, 10 Center Drive, Bldg., 10, Room 2D-57, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

References

- Bader M. Tissue renin–angiotensin-aldosterone systems: targets for pharmacological therapy. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:439–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodei S, Arrighi N, Spano P, Sigala S. Should we be cautious on the use of commercially available antibodies to dopamine receptors? Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:413–415. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burson JM, Aguilera G, Gross KW, Sigmund CD. Differential expression of angiotensin receptor 1A and 1B in mouse. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:E260–E267. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.267.2.E260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu AT, Dunscomb J, Kosierowski J, Burton CR, Santomenna LD, Corjay MH, Benfield P. The ligand binding signatures of the rat AT1A, AT1B and the human AT1 receptors are essentially identical. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;197:440–449. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasc JM, Shanmugam S, Sibony M, Corvol P. Tissue-specific expression of type 1 angiotensin II receptor subtypes. An in situ hybridization study. Hypertension. 1994;24:531–537. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.24.5.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdani N, van der Velden J. Lack of specificity of antibodies directed against human beta-adrenergic receptors. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:403–407. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häuser W, Jöhren O, Saavedra JM. Characterization and distribution of angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the mouse brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;348:101–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagami T, Guo DF, Kitami Y. Molecular biology of angiotensin II receptors: an overview. J Hypertens Suppl. 1994;12:S83–S94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Oliverio MI, Mannon PJ, Best CF, Maeda N, Smithies O, Coffman TM. Regulation of blood pressure by the type 1A angiotensin II receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3521–3525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen BC, Swigart PM, Simpson PC. Ten commercial antibodies for alpha-1-adrenergic receptor subtypes are nonspecific. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:409–412. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöhren O, Saavedra JM. Expression of AT1A and AT1B angiotensin II receptor messenger RNA in forebrain of 2-wk-old rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E104–E112. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.1.E104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöhren O, Inagami T, Saavedra JM. AT1A, AT1B, and AT2 angiotensin II receptor subtype gene expression in rat brain. NeuroReport. 1995;6:2549–2552. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199512150-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jositsch G, Papadakis T, Haberberger RV, Wolff M, Wess J, Kummer W. Suitability of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antibodies for immunohistochemistry evaluated on tissue sections of receptor gene-deficient mice. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0365-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakar SS, Sellers JC, Devor DC, Musgrove LC, Neill JD. Angiotensin II type-1 receptor subtype cDNAs: differential tissue expression and hormonal regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;183:1090–1096. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasckow J, Mulchahey JJ, Aguilera G, Pisarska M, Nikodemova M, Chen HC, Herman JP, Murphy EK, Liu Y, Rizvi TA, Dautzenberg FM, Sheriff S. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) expression and protein kinase A mediated CRH receptor signaling in an immortalized hypothalamic cell line. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:521–529. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenkei Z, Corvol P, Llorens-Cortes C. The angiotensin receptor subtype AT1A predominates in rat forebrain areas involved in blood pressure, body fluid homeostasis and neuroendocrine control. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;30:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00272-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenkei Z, Nuyt M, Grouselle D, Corvol P, Llorens-Cortes C. Identification of endocrine cell populations expressing the AT1B subtype of angiotensin II receptors in the anterior pituitary. Endocrinology. 1999;140:472–477. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.1.6397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Kalintchenko N, Sassone-Corsi P, Aguilera G. Inhibition of corticotrophin-releasing hormone transcription by inducible cAMP-early repressor in the hypothalamic cell line, 4B. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:42–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorincz A, Nusser Z. Specificity of immunoreactions: the importance of testing specificity in each method. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9083–9086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2494-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Bartfai T. Analyzing the validity of GalR1 and GalR2 antibodies using knockout mice. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:417–420. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0394-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C82–C97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel MC, Wieland T, Tsujimoto G. How reliable are G-protein-coupled receptor antibodies? Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:385–388. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0395-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TJ, Alexander RW, Griendling KK, Runge MS, Bernstein KE. Isolation of a cDNA encoding the vascular type-1 angiotensin II receptor. Nature. 1991;351:233–236. doi: 10.1038/351233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikodemova M, Kasckow J, Liu H, Manganiello V, Aguilera G. Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone promoter activity in AtT-20 cells and in a transformed hypothalamic cell line. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1292–1300. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliverio MI, Best CF, Kim HS, Arendshorst WJ, Smithies O, Coffman TM. Angiotensin II responses in AT1A receptor-deficient mice: a role for AT1B receptors in blood pressure regulation. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F515–F520. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.4.F515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliverio MI, Kim HS, Ito M, Le T, Audoly L, Best CF, Hiller S, Kluckman K, Maeda N, Smithies O, Coffman TM. Reduced growth, abnormal kidney structure, and type 2 (AT2) angiotensin receptor-mediated blood pressure regulation in mice lacking both AT1A and AT1B receptors for angiotensin II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15496–15501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M, Mehr AP, Kreutz R. Physiology of local renin angiotensin systems. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:747–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton WG, Runge M, Horaist C, Cohen C, Alexander RW, Bernstein KE. Immunohistochemical localization of rat angiotensin II AT1 receptor. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F989–F995. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.6.F989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradidarcheep W, Stallen J, Labruyère WT, Dabhoiwala NF, Michel MC, Lamers WH. Lack of specificity of commercially available antisera against muscarinergic and adrenergic receptors. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rateri DL, Moorleghen JJ, Balakrishnan A, Owens AP, III, Howatt DA, Subramanian V, Poduri A, Charnigo R, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Endothelial cell-specific deficiency of Ang II type 1a receptors attenuates Ang II-induced ascending aortic aneurysms in LDL receptor-/- mice. Circ Res. 2011;108:574–581. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. Antibodies as valuable neuroscience research tools versus reagents of mass distraction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8017–8020. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2728-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan X, Oliverio MI, Coffman TM, Arendshorst WJ. Renal vascular reactivity in mice: AngII-induced vasoconstriction in AT1A receptor null mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2620–2630. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10122620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra JM, Sánchez-Lemus E, Benicky J. Blockade of brain angiotensin II AT1 receptors ameliorates stress, anxiety, brain inflammation and ischemia: therapeutic implications. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Lemus E, Benicky J, Pavel J, Saavedra JM. In vivo angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade selectively inhibits LPS-induced innate immune response and ACTH release in rat pituitary gland. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:945–957. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB. An open letter to our readers on the use of antibodies. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:477–478. doi: 10.1002/cne.20839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB. A guide to the perplexed on the specificity of antibodies. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:1–5. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.952770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB, Sawchenko PE. Magic peptides, magic antibodies: guidelines for appropriate controls for immunohistochemistry. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:161–163. doi: 10.1002/cne.10858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasamura H, Hein L, Krieger JE, Pratt RE, Kobilka BK, Dzau VJ. Cloning, characterization, and expression of two angiotensin receptor (AT-1) isoforms from the mouse genome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;185:253–259. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi K, Saavedra JM. Characterization and development of angiotensin II receptor subtypes (AT1 and AT2) in rat brain. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R209–R216. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.1.R209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Chen Y, Dirksen WP, Morris M, Periasamy M. AT1b receptor predominantly mediates contractions in major mouse blood vessels. Circ Res. 2003;93:1089–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000101912.01071.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]