Abstract

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is an essential eukaryotic serine/threonine phosphatase known to play important roles in cell cycle regulation. Association of different B-type targeting subunits with the heterodimeric core (A/C) enzyme is known to be an important mechanism of regulating PP2A activity, substrate specificity, and localization. However, how the binding of these targeting subunits to the A/C heterodimer might be regulated is unknown. We have used the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model system to investigate the hypothesis that covalent modification of the C subunit (Pph21p/Pph22p) carboxyl terminus modulates PP2A complex formation. Two approaches were taken. First, S. cerevisiae cells were generated whose survival depended on the expression of different carboxyl-terminal Pph21p mutants. Second, the major S. cerevisiae methyltransferase (Ppm1p) that catalyzes the methylation of the PP2A C subunit carboxyl-terminal leucine was identified, and cells deleted for this methyltransferase were utilized for our studies. Our results demonstrate that binding of the yeast B subunit, Cdc55p, to Pph21p was disrupted by either acidic substitution of potential carboxyl-terminal phosphorylation sites on Pph21p or by deletion of the gene for Ppm1p. Loss of Cdc55p association was accompanied in each case by a large reduction in binding of the yeast A subunit, Tpd3p, to Pph21p. Moreover, decreased Cdc55p and Tpd3p binding invariably resulted in nocodazole sensitivity, a known phenotype of CDC55 or TPD3 deletion. Furthermore, loss of methylation also greatly reduced the association of another yeast B-type subunit, Rts1p. Thus, methylation of Pph21p is important for formation of PP2A trimeric and dimeric complexes, and consequently, for PP2A function. Taken together, our results indicate that methylation and phosphorylation may be mechanisms by which the cell dynamically regulates PP2A complex formation and function.

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A)1 is a highly conserved euphosphatase karyotic serine/threonine phosphatase known to play important roles in many cellular events including regulation of the cell cycle (reviewed in Refs. 1–3). PP2A often exists as a heterotrimeric enzyme composed of a catalytic (C) subunit, a structural (A) subunit, and a variable regulatory/targeting (B-type) subunit (1, 4). In mammalian cells, three major families of B-type subunits, B (or B55), B′ (or B56), and B″ (or PR72/130), have been described (1). Binding of B-type subunits to the A/C core heterodimer modulates PP2A activity (5–11) and localizes PP2A to specific cellular microenvironments and/or signaling pathways (for examples, see Refs. 12–15).

Although it is clear that binding of B-type targeting subunits is a major mechanism by which cells regulate PP2A, how the binding of these targeting subunits to the A/C heterodimer might be regulated is unknown. Recently, we showed in mammalian cells that deletion of nine C subunit carboxyl-terminal residues (amino acids 301–309) or nonconservative substitution of threonine 304 or tyrosine 307 abolished the ability of the C subunit to form complexes with the B subunit (10). Based on this finding, we postulated that reversible covalent modification at the C subunit carboxyl terminus might regulate B subunit binding.

Previous studies showed that both phosphorylation and methylation occur on the C subunit carboxyl terminus. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 307 in vitro by pp60c-src results in 90% inhibition of PP2A activity (16). Substitution of this same tyrosine with an acidic residue abolishes binding of the A/C heterodimer to B subunit in vivo, suggesting that phosphorylation of this residue might do the same (10). PP2A is also known to be inhibited by phosphorylation of an unknown threonine residue (17), and interestingly, substitution of threonine 304, located in the carboxyl terminus of the C subunit, also abolishes B subunit binding (10).

The effects of reversible methylation of leucine 309 (18 –22) on PP2A activity is unclear (20, 23, 24). C subunit methylation appears to occur in vivo in a cell cycle-regulated manner (25) and, thus, could be a mechanism for modulating PP2A function in a cell cycle-specific manner. Because PP2A methylation is reversible and the methyltransferase (23) and methylesterase (26) enzymes have recently been cloned, PP2A methylation represents an attractive model system for the study of the effects of reversible protein methylation on protein-protein interactions.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome contains two genes (PPH21 and PPH22) encoding PP2A catalytic subunits (27) and a single A subunit gene, TPD3 (28). Deletion of either PPH21 or PPH22 alone has no effect on yeast growth, although PP2A activity is reduced by 51 and 33%, respectively (27). Double deletion of both genes results in severe slow growth and a temperature-sensitive phenotype (29). Additional deletion of the PPH3 gene, which encodes a nonessential protein phosphatase that has residual overlapping function with PP2A, leads to cell death (29). S. cerevisiae has two B-type subunits, Cdc55p and Rts1p, that are, respectively, homologous to the B and B′ mammalian B-type subunit families (30, 31). Cells lacking Cdc55p or Tpd3p are sensitive to drugs such as nocodazole and benomyl, which perturb microtubule stability, presumably because forms of PP2A containing these subunits are important for normal mitotic spindle checkpoint function (32, 33).

Although only one S. cerevisiae methylesterase homolog (Ppe1p) exists that was found to be nonessential for growth under normal conditions (26), two putative PP2A methyltransferase homologs (Ppm1p and Ppm2p) exist (23) whose importance has not yet been determined. The first, Ppm1p, is highly homologous to the mammalian PP2A methyltransferase (PMT1) that was recently cloned, expressed, and shown to have activity by De Baere et al. (23). These authors also reported the existence of a second homologous protein in both mammalian cells (PMT2) and S. cerevisiae (Ppm2p) that has ~350 additional amino acids containing significant similarity to the kelch domain (23), which has been implicated in actin binding. To date, Ppm1p, Ppm2p, and the human Ppm2p homolog have not been shown to have PP2A methyltransferase activity, and therefore, the relative contributions of these enzymes toward methylating PP2A in vivo are not known.

We previously created a set of mutants targeting highly conserved residues in the carboxyl terminus of the mammalian PP2A catalytic (C) subunit. Several of these mutants showed decreased binding of B subunit and, in some cases, decreased C subunit methylation (10).2 Expression of these mutants in mammalian cells showed no consistent phenotype3 perhaps because of the high level of endogenous wild-type (wt) C subunit. In this study, we have generated S. cerevisiae cells whose survival depends on the expression of the corresponding yeast (Pph21p) mutants. Analysis of these cells together with strains deleted for the putative PP2A methyltransferase genes, PPM1 and PPM2, reveals that carboxymethylation of the yeast C subunit carboxyl terminus is required for the efficient assembly of PP2A heterotrimers containing Cdc55p or Rts1p. Given that C subunit methylation is known to be reversible and to oscillate in a cell cycle-dependent manner in mammalian cells, these results suggest that the cell may regulate B-type subunit binding and, consequently, PP2A function by modulating the methylation of the PP2A catalytic subunit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and PPH21 Mutant cDNAs

A 2.5-kilobase polymerase chain reaction product (forward primer, CGGGATCCGAGAGCAAAT-CGTTAAGTTCAGG; reverse primer, ACGCGTCGACGCTCAATACTC-GAGTTATTCGTGTG) encoding the PPH21 gene was cut with BamHI and SalI and ligated into pBluescript SK+ vector (Stratagene). The two nucleotides preceding the ATG start codon were then mutated to CC by site-directed polymerase chain reaction mutagenesis to create an NcoI site (CCATGG) that includes the start codon. Subsequently, site-directed polymerase chain reaction mutagenesis was used to create the T364A (codon change: ACG to GCT), T364D (codon change: ACG to GAC), Y367E (codon change: TAC to GAA), Y367F (codon change: TAC to TTC), and L369Δ (deleted codon) mutations. Wt and mutant PPH21 cDNAs were then subcloned into pRS316 (CEN6 URA3 amp) (35), pPS310 (CEN6 URA3 GAL1–10 amp) (36), pRS425 (2μ URA3 amp) (35), or pRS423 (2μ TRP1 amp) (35) vectors. Amino-terminal epitopetagged versions of the mutants in pRS316 and pRS425 vectors were also made by inserting double-stranded oligonucleotides encoding the influenza hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (Tyr-Pro-Tyr-Asp-Val-Pro-Asp-Tyr-Ala) followed by the thrombin recognition site (Leu-Val-Pro-Arg-Gly-Ser) just before the start ATGs, making use of the NcoI site created previously. A pRS315 construct (RTS1::his6) expressing Rts1p with a carboxyl-terminal 6×His epitope tag (Rts1p-6×His) was obtained from R. Hallberg (37).

Growth Media and Yeast Strains

S. cerevisiae strain W303a (MATa ura3–1 leu2–3, 112 trp1–1 his3–11, 15 ade2–1 can1–100) and its isogenic derivative ADR496 (MATa ura3–1 leu2–3, 112 trp1–1 his3–11, 15 ade2–1 can1–100 CDC55::HIS3) were obtained from A. Murray (32). Strain H328 (MATa ade2–1 can1–100 his3–11, 15 leu2–3, 112 trp1–1 ura 3–1 PPH21Δ::HIS3 GAL1/10:PPH22 PPH3::LEU2) was obtained from J. Ariño (29, 46). Strains BY4741 (MATa his3 leu2 met15 ura3), YDP16650 (MATα PPM2Δ::KAN his3 leu2 lys2 ura3), and YDP4271 (MATα PPM1Δ::KAN his3 leu2 met15 ura3) were obtained from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL). Strain YDP5D (MATa PPM1Δ::KAN PPM2Δ::KAN his3 leu2 lys2 ura3 met15) was made by mating YDP16650 and YDP4271, sporulating, and selecting the appropriate spore. Growth media were prepared according to standard recipes (38) or obtained from BIO101 (Carlsbad, CA).

Antibodies

Rabbit anti-Cdc55p polyclonal antibody was raised to a fusion protein containing a 6×His tag fused to the first 193 amino acids of Cdc55p. Rabbit anti-Tpd3p antibody was raised to a fusion protein containing a amino-terminally 6×His-tagged Tpd3p protein lacking 64 amino-terminal amino acids and 38 carboxyl-terminal residues. Histidine tag (His probe; H-15) antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Methylation-sensitive (binding inhibited by methylation of the C subunit) anti-PP2A C subunit monoclonal antibody clone 1d6 was generated against a 15-residue unmethylated carboxyl-terminal peptide with an additional amino-terminal cysteine added for coupling to keyhole limpet hemocyanin2 and is now carried by Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. Anti-HA tag antibodies, 12CA5 and 16B12, were obtained from Berkeley Antibody Co. (BAbCo).

Preparation of Cellular Extracts Immunoprecipitations and Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested and lysed as described (39), except that vortexing of cells with glass beads was done for 45 s intervals. Immunoprecipitation of PP2A complexes via HA-tagged wt or mutant C subunits (Pph21p) was performed using anti-HA tag monoclonal antibody (12CA5) plus protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as described (39), except that 300 μl of lysate was immunoprecipitated with 2 μg of antibody for 90 min at 4 °C. In some immunoblots, anti-mouse κ light chain secondary antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, AL) were used to reduce background at the position of HA-tagged Pph21p.

Nocodazole Sensitivity Assay

Yeast cells were grown at 30 °C overnight. Cell numbers were counted, and cultures were diluted to ~2 × 105 cells/ml and grown to log phase in medium containing 10 or 40 μg/ml nocodazole. At 0 (before nocodazole addition), 4, and 6 h, cells were removed and diluted 10-fold, and 50 μl was spread on each of three YPD plates. After incubation of these plates at 30 °C for 2 days, the percent survival of each sample was calculated by dividing the mean of the colony numbers at each time point by the mean of the colony numbers at time 0 and multiplying by 100.

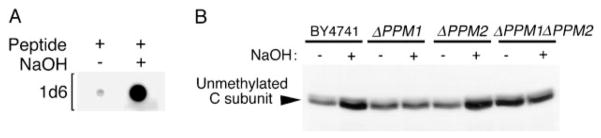

Use of Methylation-sensitive C Subunit Monoclonal Antibody, 1d6, to Assay C Subunit (Pph21p/Pph22p) Methylation

This assay2 uses a methylation-sensitive mouse monoclonal antibody (1d6) rather than a polyclonal antibody (20, 25) to evaluate PP2A methylation. 1d6 was generated against an unmethylated PP2A carboxyl-terminal peptide and almost exclusively detects unmethylated PP2A. Fig. 5A shows that its binding to a mammalian C subunit carboxyl-terminal nonapeptide is inhibited by methylation of the carboxyl-terminal leucine. The non-apeptide has only one conservative difference from the Pph22p sequence: a lysine instead of an arginine at its second position. 1d6 recognizes both unmethylated Pph21p and unmethylated Pph22p. 1d6 immunoblotting plus and minus base treatment can be used to determine the C subunit methylation status as described in the legend to Fig. 5B. This method has the advantage over radiolabeling methylation assays in that it measures the steady-state methylation level of C subunit directly, avoiding potential problems with label uptake and incorporation.

Fig. 5. PPM1 encodes the major PP2A methyltransferase in S. cerevisiae.

A, 1d6 monoclonal antibody specifically recognizes unmethylated PP2A carboxyl-terminal peptide. A C subunit carboxyl-terminal nonapeptide carboxymethylated on leucine (described under “Materials and Methods”) was synthesized and high performance liquid chromatography-purified. 0.25 μg of this peptide was demethylated by treatment with 0.5 M NaOH (+) for 5 min on ice and then neutralized, whereas another 0.25 μg of peptide (−) was treated with an equivalent amount of preneutralized solution. The unmethylated and methylated aliquots of the peptides were then spotted onto nitrocellulose, and the membrane was probed with 1d6 monoclonal antibody. B, deletion of PPM1 results in nearly complete loss of PP2A methylation. Lysates were prepared from wt (BY4741), Δ PPM1, Δ PPM2, and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells in the presence of 200 nM okadaic acid to prevent further methylation and demethylation (19). Twenty μl of each lysate (+) was placed on ice and demethylated by the addition of 10 μl of 0.5 M NaOH. After a 5-min incubation, the samples were neutralized with an equivalent volume of 0.5 M HCl and one-half volume of 2 M Tris, pH 6.8. Another 20 μl of each lysate (−) was combined with an equivalent amount of preneutralized base solution. Then the samples were analyzed by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted with methylation-sensitive C subunit monoclonal antibody (1d6; 1:10,000). Because 1d6 almost exclusively recognizes unmethylated Pph21p and Pph22p, the ratio of signal intensity between the −base lane (in vivo amount of unmethylated C subunit) and the +base lane (100% unmethylated) indicates the percentage of C subunit that is unmethylated in vivo. The percent unmethylated C subunits was subtracted from 100 to obtain the percentage of methylated C subunits (see values under “Results”). S. cerevisiae C subunits migrated as tight doublets in this gel, but whether double or single bands are seen can vary.

RESULTS

Carboxy-terminal Pph21p Mutants Are Functional

To investigate the possibility that PP2A might be regulated by reversible covalent modification of its carboxyl terminus, we previously created and analyzed a set of mutants targeting highly conserved residues in the carboxyl terminus of the mammalian PP2A catalytic (C) subunit (10) (see examples in Table I). Several of these mutants showed decreased binding to B subunit (10) and, in some cases, decreased C subunit methylation.2 The lack of a consistent phenotype in mammalian cells prompted us to move to a model system that was more amenable to genetic manipulation. Because the carboxyl terminus of PP2A is highly conserved from yeast to humans and PP2A methylation is conserved in yeast (40), we chose to construct cDNAs expressing S. cerevisiae Pph21p versions of a subset of these mutants (T364A, T364D, Y367E, Y367F, and L369Δ; see “Materials and Methods” and Table I) and to study these mutants in S. cerevisiae cells whose viability depends on their expression.

Table I.

B subunit binding of selected mammalian C subunit mutants and properties of the corresponding S. cerevisiae C subunit (Pph21p) mutants used in this study

| Mammalian

|

S. cerevisiae

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C subunita | B subunit bindinga | C subunit (Pph21p) | Supports H328 growth on YPDb | Tsc | Binds Cdc55pd | Nocodazole sensitivityc |

| Vector | N/A | Vector | − | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| WT(309aa)e | + | WT (369aa)e | + | − | + | − |

| T304A | + | T364A | + | − | + | − |

| T304D | − | T364D | + | − | − | ++ |

| Y307E | − | Y367E | + | ++ | − | ++ |

| Y307F | + | Y367F | + | + | + | + |

| L309Δ | − | L369Δ | + | + | NT | ++ |

Data are from Fig. 1.

Data are from Figs. 3 and 4. Ts, temperature-sensitive for growth at 37 °C. For these assays: ++, severe; +, intermediate; −, not consistently detectable; N/A, not applicable.

Data are from Fig. 2. N/A, not applicable; NT, not tested (because the HA-tagged version of this mutant could not be expressed).

WT yeast C subunit has 369 amino acids (aa), whereas WT mammalian C subunit has 309.

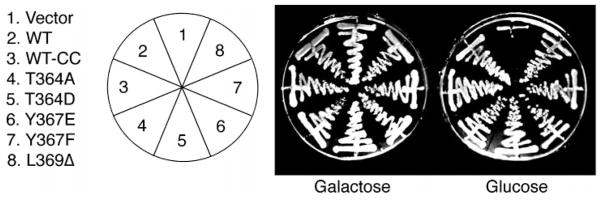

Ronne et al. (29) previously created an S. cerevisiae strain (H328) deleted for PPH21 and PPH3 that expresses Pph22p under control of the GAL promoter. H328 is viable when grown in the presence of galactose but is inviable on glucose, indicating that these cells are dependent on production of Pph22p from the galactose-inducible promoter for viability. To determine whether our Pph21p mutants could support viability, H328 cells were transformed with plasmids expressing wt or mutant C subunits or vector only and then grown on galactose or glucose. Fig. 1 shows that although H328 cells transformed with empty vector are inviable on glucose, all the mutants could support growth of these cells on glucose, indicating that these mutant proteins are functional. Because leucine 369 is the site of PP2A carboxymethylation in S. cerevisiae, this result also suggests that methylation of Pph21p is not essential for cell viability.

Fig. 1. Carboxyl-terminal C subunit mutants are functional.

Cells were transformed with pRS316 plasmid encoding the various carboxyl-terminal Pph21p mutants and grown on media containing galactose or glucose. WT-CC and all mutants have the two nucleotides just upstream of the ATG start codon changed to CC to create a NcoI site for additional constructs (see “Materials and Methods”). As can be seen, this change did not affect the ability of wt Pph21p to support growth of these cells on glucose.

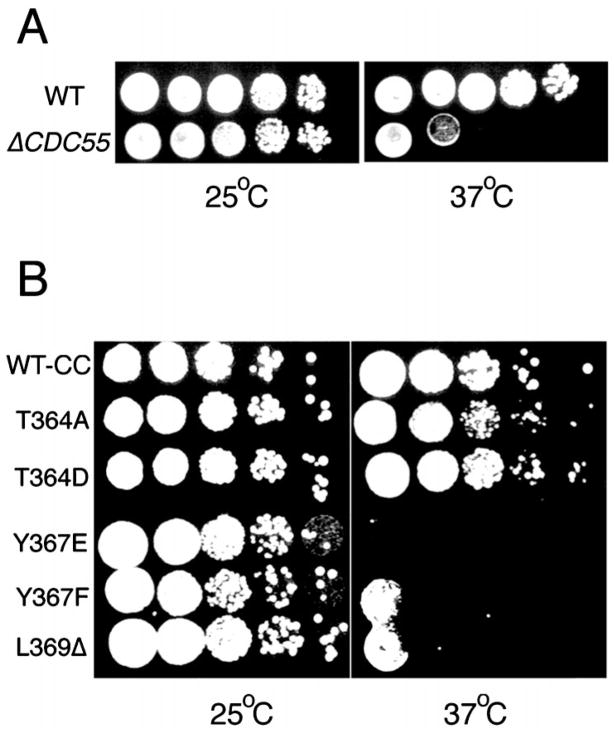

The Importance of C Subunit Carboxy-terminal Residues for Interaction with B Subunit Is Highly Conserved between Mammals and Yeast

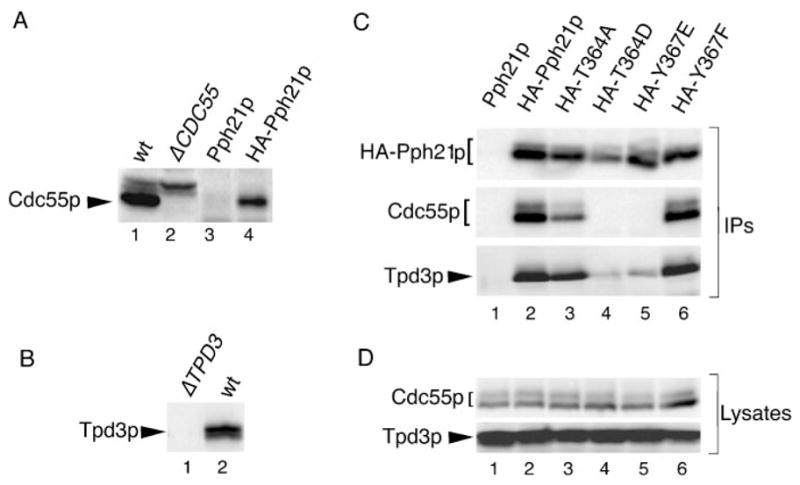

We next analyzed amino-terminal HA-tagged versions of all the Pph21p carboxyl-terminal point mutants except L369Δ for their ability to bind Cdc55p by immunoprecipitating them via their epitope tag and immunoblotting for coimmunoprecipitated Cdc55p. For unknown reasons, the addition of an amino-terminal HA tag to L369Δ resulted in undetectable expression of this mutant using several different constructs, and HA-tagged L369Δ was unable to support the growth of H328 cells. As described under “Materials and Methods,” we raised a polyclonal antibody to Cdc55p to use in this assay. Fig. 2A shows the characterization of this antibody and the validation of the coimmunoprecipitation assay. As expected, the antibody detected a strong Cdc55p band in lysates from wt cells (lane 1) that was missing in lysates from cells deleted for CDC55 (Δ CDC55; lane 2). Preimmune serum from the same rabbit did not detect the Cdc55p band (not shown). In addition, the antibody easily detected Cdc55p coimmunoprecipitated with HA-tagged wt C subunit (lane 4), whereas a parallel immunoprecipitate (lane 3) from cells expressing untagged wt Pph21p had no detectable Cdc55p.

Fig. 2. Substitution of threonine 364 or tyrosine 367 with an acidic residue abrogates C subunit interaction with Cdc55p and decreases its interaction with Tpd3p, whereas substitution with more conservative residues does not.

A, characterization of the Cdc55p antibody. 12CA5 immunoprecipitates were prepared from H328 cells expressing untagged Pph21p (Pph21p) or HA-tagged Pph21p (HA-Pph21p) and analyzed along with cell lysates from W303a (wt) and ADR496 (Δ CDC55) by immunoblotting with anti-Cdc55p rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:5000). All lanes are from the same gel but were not all originally adjacent. The dark exposure shown reveals no trace of Cdc55p signal in the deletion strain. B, characterization of the Tpd3p antibody. Immunoblots of cell lysates from W303a cells lacking Tpd3p (Δ TPD3) and from W303a cells (wt) were probed with anti-Tpd3p rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:5000). C, Cdc55p coimmunoprecipitates with T364A and Y367F but not with T364D or Y367E. H328 cells expressing the indicated Pph21p proteins were grown in glucose-containing medium. 12CA5 immunopre-cipitates prepared from lysates of these cells were immunoblotted with anti-Cdc55p and anti-Tpd3p antibodies (IPs). Even on long exposures, no Cdc55p could be seen coimmunoprecipitating with Y364D and Y367E, whereas a small amount of Tpd3p was detected. Pph21p mutants migrate as doublets in these gels, but whether double or single bands are seen can vary. This pattern of migration in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis has been noted previously for endogenous and epitope-tagged mammalian PP2A C subunits (10, 25, 34) and does not appear to be due to degradation. D, Cdc55p and Tpd3p are still present in H328 cells expressing mutant Pph21p proteins. Lysates from H328 cells expressing the various wt and mutant Pph21p proteins (same order of lanes as in panel C) were immunoblotted for Cdc55p and Tpd3p.

Fig. 2C shows the results of analyzing Cdc55p binding to all the Pph21p mutants except L369Δ. Although the control immunoprecipitate from cells expressing untagged Pph21p (lane 1) again contained no detectable Cdc55p, Cdc55p was specifically coimmunoprecipitated with wt HA-Pph21p and with the HA-tagged T364A and Y367F mutants (lanes 2, 3, and 6, respectively). In contrast, Cdc55p could not be detected in immunoprecipitates of T364D (lane 4) or Y367E (lane 5) even on long exposures. These results parallel those obtained previously with the corresponding mammalian mutants (Table I), indicating that the roles of these residues in B subunit binding are highly conserved.

When these same immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-Tpd3p antibody (characterized in Fig. 2B), T364D and Y367E were found to bind greatly reduced levels of Tpd3p compared with wt Pph21p, T364A, and Y367F (Fig. 2C). However, the effect of acidic substitution of Thr-364 and Tyr-367 on Tpd3p binding was less dramatic than on the association of Cdc55p. Decreased A subunit binding was also found previously for the corresponding mammalian C subunit tyrosine mutant (Y307E) but not for the corresponding mammalian threonine mutant (T304D) (10).

To determine whether loss of Cdc55p and Tpd3p binding affects the levels of these proteins in cells, lysates from cells expressing wt or mutant Pph21p proteins were probed with antibodies to these proteins. Similar levels of these two proteins were found in all samples (Fig. 2D), indicating that decreased binding did not impact protein stability in vivo.

Mutations in Tyrosine 367 Cause a Temperature-sensitive Phenotype

Previously, a strain deleted for CDC55 was reported to be cold-sensitive (30) but not temperature-sensitive (28). Because the strain expressing our mutants, H328, has a different parental background (W303a) than the strain for which Δ CDC55 cold sensitivity was reported, we first analyzed the growth of a W303a CDC55 deletion strain (ADR496) at different temperatures. Although we could not detect a cold-sensitive phenotype (data not shown), this strain demonstrated a moderate temperature-sensitive phenotype (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. A CDC55 deletion strain and H328 cells expressing Y367E, Y367F, L369Δ are temperature-sensitive.

A, deletion of CDC55 in a W303a background is temperature-sensitive. W303a cells with an intact CDC55 gene (WT) or with CDC55 deleted (Δ CDC55) were grown to saturation at 25 °C. 10-Fold serial dilutions were spotted onto YPD plates and incubated at 25 or 37 °C. B, H328 cells expressing Y367E, Y367F, or L369Δ are temperature-sensitive, whereas those expressing T364A or T364D are not. Cells were grown to saturation at 25 °C. 10-Fold serial dilutions were then spotted onto YPD plates and incubated at 25 or 37 °C. For presentation, data from two different plates were photographically merged for each panel. In repeated experiments, Y367E always showed a more severe temperature-sensitive phenotype than T367F, L369Δ, and the CDC55 deletion strain. WT-CC and all mutants have the two nucleotides just upstream of the ATG start codon changed to CC in order to create a NcoI site for additional constructs (see “Materials and Methods”).

To determine whether any of the C subunit mutants were temperature-sensitive or cold-sensitive for growth, H328 cells expressing untagged wt or mutant Pph21p proteins were tested for growth at 14, 25, and 37 °C. Although none of the mutants displayed a cold-sensitive phenotype (data not shown), several mutants were temperature-sensitive (Fig. 3B). Y367E showed the most severe temperature-sensitive phenotype, whereas Y367F and L369Δ showed intermediate sensitivity. wt Pph21p, T364A, and T364D did not demonstrate a temperature-sensitive phenotype. Thus, the temperature sensitivity of the mutants appears to be residue-specific. Furthermore, this temperature-sensitive phenotype does not correlate with their ability to bind Cdc55p in our assay (Table I).

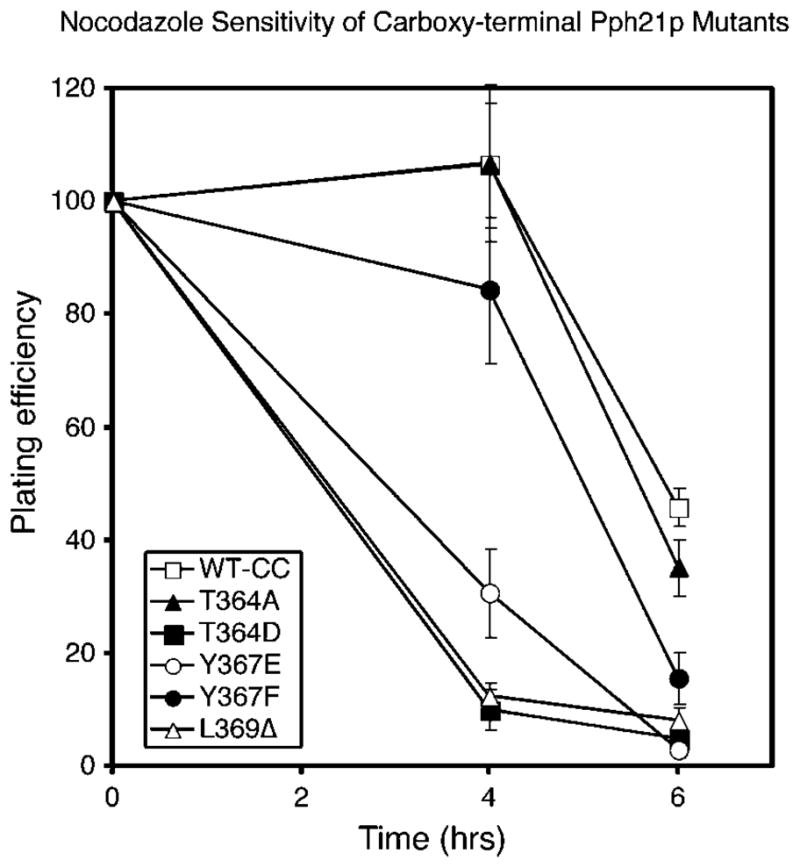

Cells Expressing C subunit Mutants Defective in Cdc55p and Tpd3p Binding Are Nocodazole-sensitive

Several laboratories have shown that deletion of CDC55 or TPD3 results in sensitivity to the microtubule depolymerizing drug, nocodazole (32, 33). To determine whether decreased binding of Cdc55p and Tpd3p to C subunit results in the same phenotype in cells expressing wt Cdc55p and Tpd3p, we tested whether H328 cells expressing Pph21p mutants unable to stably bind Cdc55p were more sensitive to nocodazole than H328 cells expressing wt Pph21p. Fig. 4A shows that cells expressing T364D, Y367E, or L369Δ were very sensitive to nocodazole treatment, whereas cells expressing T364A showed the same sensitivity to the drug treatment as cells expressing wt Pph21p. T364D and Y367E do not bind Cdc55p, and from the mammalian data (Table I), L369Δ would be predicted not to bind. Decreased Cdc55p/Tpd3p binding therefore correlates well with nocodazole sensitivity. The only exception was that cells expressing Y367F had intermediate nocodazole sensitivity and yet bound similar amounts of Cdc55p and Tpd3p as T364A, which had wt sensitivity. This result suggests that Y367F has an additional defect.

Fig. 4. Cells expressing Pph21p mutants defective in binding Cdc55p and Tpd3p are nocodazole-sensitive.

H328 cells expressing wt Pph21p or the indicated mutants from the pRS316 vector were grown overnight and then treated with nocodazole (see “Materials and Methods”). At 4 and 6 h of treatment, cells were diluted and plated on YPD plates. After incubation, colonies were counted to determine percent survival. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of values obtained from triplicate plates. WT-CC and all mutants have the two nucleotides just upstream of the ATG start codon changed to CC in order to create a NcoI site for additional constructs (see “Materials and Methods”).

PPM1 but Not PPM2 Encodes the Major PP2A Methyltransferase

We hypothesized that mutation of certain C subunit carboxyl-terminal residues may affect Cdc55p and Tpd3p binding indirectly by altering methylation of leucine 369. In particular, the fact that loss of leucine 369 causes sensitivity to nocodazole suggested that methylation of this residue might affect Cdc55p and Tpd3p function via regulation of PP2A complex formation. We therefore used a combined genetic and biochemical approach in S. cerevisiae to determine whether methylation of Pph21p is required for Cdc55p and/or Tpd3p association with C subunit and, consequently, for Cdc55p and/or Tpd3p function as assayed by resistance to nocodazole.

First, the steady-state in vivo C subunit methylation levels of wt cells and of cells deleted for one or both of the putative S. cerevisiae methyltransferase genes (Δ PPM1, Δ PPM2, and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2) were compared using an assay employing a methylation-sensitive monoclonal antibody, 1d6, which is specific for unmethylated C subunit (see “Materials and Methods” and Fig. 5). Because base treatment demethylates C subunits, a lysate with methylated C subunits will have an increase in 1d6 signal intensity upon treatment with base, whereas a lysate containing only unmethylated C subunits will have no increase. Fig. 5B shows that deletion of PPM1 caused a great decrease in C subunit methylation in vivo, whereas deletion of PPM2 had at best a small effect. Quantitation of four independent experiments determined that although C subunits in the wt (BY4741) and Δ PPM2 strains are methylated at 58 ± 9 and 54 ± 10%, respectively, C subunits in Δ PPM1 and Δ PPM1Δ-PPM2 strains are methylated at 9.6 ± 12.5 and <1%, respectively. These results indicate that PPM1 encodes the major Pph21p/Pph22p methyltransferase. Moreover, cells deleted for PPM1, PPM2, or both PPM1 and PPM2 grow normally at room temperature (data not shown), suggesting that C subunit methylation is not essential for cell growth at this temperature.

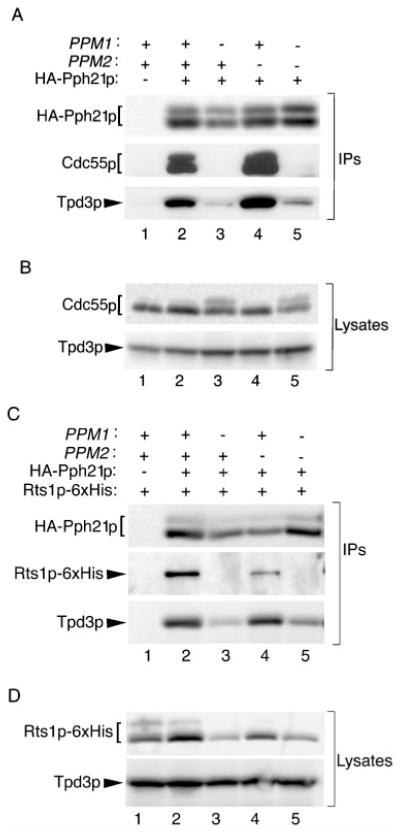

Deletion of PPM1 Greatly Reduces Cdc55p, Tpd3p, and Rts1p Binding

If C subunit methylation is necessary for stable formation of PP2A heterotrimers containing Cdc55p, then deletion of PPM1 should result in a decrease of Cdc55p binding to C subunit. To test this hypothesis, lysates from wt, Δ PPM1, Δ PPM2, and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells expressing HA-tagged Pph21p were immunoprecipitated with HA tag antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were probed for the presence of Cdc55p (Fig. 6A). Although Cdc55p could be coimmunoprecipitated with Pph21p in wt (lane 2) and Δ PPM2 cells (lane 4), it could not be coimmunoprecipitated with Pph21p in Δ PPM1 (lane 3) and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 (lane 5) cells. Thus, deletion of PPM1, which results in predominantly unmethylated Pph21p, disrupts Cdc55p binding to C subunit, whereas loss of PPM2, which has little effect on Pph21p methylation, has no detectable effect. To determine whether binding of Tpd3p was also affected, the same immunoprecipitates were probed for Tpd3p. Fig. 6A shows that loss of methylation also resulted in a large reduction in Tpd3p association.

Fig. 6. Deletion of PPM1, but not PPM2, results in decreased Cdc55p, Tpd3p, and Rts1p binding to Pph21p.

A, Cdc55p no longer associates stably with Pph21p, and Tpd3p binding is greatly reduced in cells deleted for PPM1. Wt (BY4741; lane 2), Δ PPM1 (lane 3), Δ PPM2 (lane 4), and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 (lane 5) cells expressing HA-tagged Pph21p from the GAL1–10 promoter and vector-only wt cells (lane 1) were grown in galactose-containing media. Anti-HA tag (12CA5) immunoprecipitates (IPs) prepared from lysates of these cells were probed sequentially with anti-Cdc55p, anti-Tpd3p, and anti-HA tag (16B12) antibodies. B, Cdc55p and Tpd3p are still present at normal levels in cells deleted for PPM1. Lysates from the same cells used in panel A (same order of lanes) were immunoblotted for Cdc55p and Tpd3p. The variation in amount of shifted Cdc55p seen in this experiment was not consistently seen in all experiments. C, deletion of PPM1 results in reduced Rts1p binding to Pph21p. Cell lysates were prepared from wt (BY4741; lanes 1–2), Δ PPM1, Δ PPM2, and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells expressing both 6×His-tagged Rts1p (Rts1p-6×His) and HA-tagged Pph21p (lanes 2–5) or vector only (lane 1). Anti-HA tag (12CA5) immunoprecipitates were prepared from these lysates and probed for the presence of Rts1p-6×His and Tpd3p using anti-6×His tag and anti-Tpd3p antibodies. D, levels of Rts1p and Tpd3p in the various cells used in panel C. Lysates from the same cells used in panel C (same order of lanes) were immunoblotted for Rts1p-6×His and Tpd3p.

To assess whether decreased binding of Cdc55p and Tpd3p to C subunit affects the levels of these proteins in cells, lysates from vector only, wt, Δ PPM1, Δ PPM2, and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells were probed with antibodies to these proteins. Similar levels of these two proteins were found in all cell lines (Fig. 6B), indicating that deletion of methyltransferase did not impact protein stability in vivo.

To determine whether methylation is important for binding of the yeast B′ subunit, Rts1p, lysates from wt, Δ PPM1, Δ PPM2, and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells expressing both HA-tagged Pph21p (or vector only) and carboxyl-terminal 6×His-tagged Rts1p (Rts1p-6×His) were immunoprecipitated with HA tag antibody. Probing of the immunoprecipitates for the presence of Rts1p-6×His using an anti-6×His tag antibody (Fig. 6C) showed that Rts1p-6×His coimmunoprecipitated specifically with HA-tagged C subunits from wt and Δ PPM2 cells but was not detectable in HA-tag immunoprecipitates from cells deleted for PPM1. Moreover, Tpd3p association was again found to be greatly reduced (Fig. 6C). Thus, methylation appears to be important for binding of Cdc55p, Tpd3p, and Rts1p to Pph21p.

To determine whether Rts1p-6×His was expressed at similar levels in these cells, lysates were probed with Tpd3p and anti-6×His tag antibodies. Relative to Tpd3p, Rts1p-6×His was expressed at a lower level in Δ PPM1 and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells than in wt and Δ PPM2 cells (Fig. 6D). It is not possible to distinguish whether the reduced levels of Rts1p-6×His expression in Δ PPM1 and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells are a cause or an effect of decreased association with C subunit. Although this lower level of expression is not sufficient to account for all the reduction in Rts1p-6×His association seen in Fig. 6C, it makes it difficult to determine the exact amount of reduction in Rts1p-6×His binding due to loss of C subunit methylation. When Rts1p-6×His was immunoprecipitated from lysates of these cells with an anti-6×His antibody, reduced but detectable levels of HA-Pph21p were found in Δ PPM1and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells compared with wt and Δ PPM2 cells (data not shown), indicating that Rts1p-6His binding is reduced but not abolished.

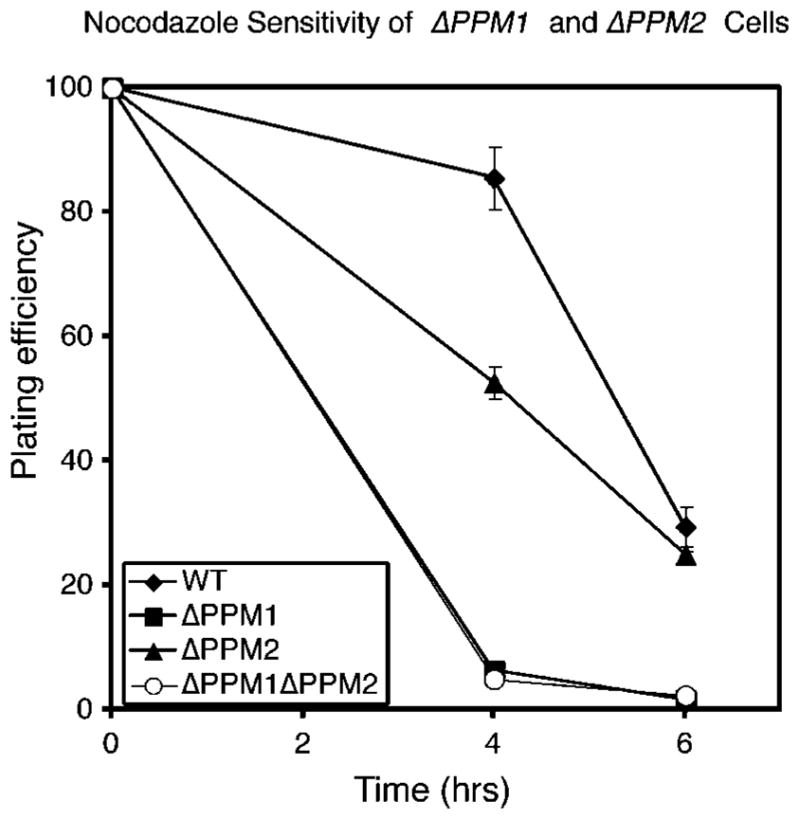

Deletion of PPM1 Leads to Nocodazole Sensitivity

Wt, Δ PPM1, Δ PPM2, and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells were next analyzed for nocodazole sensitivity as a functional assay for loss of Cdc55p and Tpd3p association. Δ PPM1 and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 cells were much more sensitive than wt cells to nocodazole treatment, indicating that deletion of PPM1 generates a phenotype consistent with loss of Cdc55p and Tpd3p association (Fig. 7) (32, 33). Although in the experiment shown, Δ PPM2 cells appeared to show some sensitivity to nocodazole at 4 h, they were wt in their sensitivity at 6 h, demonstrating that they did not have a substantially greater sensitivity to nocodazole than wt cells. Thus, loss of PPM1, but not of PPM2, leads to loss of C subunit methylation. This, in turn, appears to result in a large decrease in C subunit association with Cdc55p and Tpd3p, inducing sensitivity to nocodazole.

Fig. 7. Cells deleted for PPM1 are nocodazole-sensitive.

Cells were grown overnight and then treated with nocodazole (see “Materials and Methods”). At 4 h and 6 h of treatment, cells were diluted and plated on YPD plates. After incubation, colonies were counted to determine percent survival. Error bars indicate the S.D. of values obtained from triplicate plates.

DISCUSSION

PP2A plays important roles in many cellular processes, and consequently, the cell controls its activity, localization, and substrate specificity through a complex set of covalent and noncovalent mechanisms. We have used the budding yeast S. cerevisiae as a model system to investigate the hypothesis that covalent modification of the C subunit (Pph21p) carboxyl terminus modulates PP2A complex formation. Our results demonstrate that Cdc55p binding to Pph21p was disrupted by either acidic substitution of potential carboxyl-terminal phosphorylation sites or by deletion of the gene for the yeast PP2A methyltransferase homolog, Ppm1p, which resulted in almost complete loss of Pph21p methylation. Loss of Cdc55p association was accompanied in each case by a large reduction in Tpd3p binding to C subunit. Moreover, decreased Cdc55p and Tpd3p binding invariably resulted in nocodazole sensitivity, a known phenotype of CDC55 or TPD3 deletion. Furthermore, our data show that loss of methylation also greatly reduces Rts1p association. Thus, methylation of Pph21p is important for formation of PP2A trimeric and dimeric complexes and, consequently, for PP2A function. These results provide the first example of the physiological importance of reversible carboxymethylation of PP2A C subunit.

Very little is known about the potential effects of reversible protein methylation at a single residue. Our findings provide evidence that this modification is capable of regulating protein-protein interactions in a manner similar to phosphorylation. The total amount of C subunit in mammalian cells is known to be tightly regulated and does not appear to vary over the course of the cell cycle (41). Because methylation of PP2A C subunit has been shown to fluctuate during the cell cycle in mammalian cells (25), methylation may be a key mechanism for regulating PP2A function in a cell cycle-dependent manner.

Our results show that Ppm1p is the major PP2A methyltransferase in S. cerevisiae. Although deletion of PPM2 did not lead to significant change of the methylation level of Pph21p, we could not rule out that Ppm2p might have some PP2A methyltransferase activity. Instead, in repeated experiments, we found that the level of unmethylated Pph21p in Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 was slightly higher than in Δ PPM1, suggesting that Ppm2p may have low methyltransferase activity in vivo, perhaps on a specific subpopulation of PP2A or at a specific time in the cell cycle. Because Ppm2p has an ~350-amino acid extension that may be involved in actin binding, Ppm2p might localize to actin-containing structures (23) and be responsible for methylating a small fraction of C subunit localized to that part of the cytoskeleton.

Deletion of PPM1 led not only to decreased Cdc55p, Tpd3p, and Rts1p binding but also to nocodazole sensitivity. The nocodazole sensitivity may be due to loss of Cdc55p and/or Tpd3p binding because previous studies have demonstrated that deletion of CDC55 or TPD3 leads to nocodazole sensitivity (32, 33). However, we cannot rule out an effect of Rts1p or another, unknown regulatory subunit whose binding may be affected by methylation. In any case, our results clearly show that changes in C subunit methylation can affect the function of PP2A in vivo.

The effects of mutation or methylation on the binding of one or more of the PP2A subunits could be indirect. Tpd3p has been shown to be required for Rts1p binding to C subunit (31), and Cdc55p presumably has a similar requirement based on mammalian in vitro data. However, the fact that mutation or loss of methylation leads to a more severe effect on Cdc55p binding than Tpd3p association suggests that loss of Cdc55p binding is not solely due to loss of Tpd3p association. Instead, decreased Cdc55p association may be directly affected by mutation or loss of C subunit methylation and cause a destabilization of A(Tpd3p)/C subunit heterodimeric complexes.

Deletion of the CDC55 gene has previously been shown to result in a cold-sensitive phenotype (30). However, our findings have shown that ADR496, a CDC55 deletion strain, displays a temperature-sensitive phenotype, suggesting that Cdc55p may be important in this strain for response to stress induced by elevated temperature. RTS1 or TPD3 deletion is also known to cause a temperature-sensitive growth phenotype. H328 cells expressing the T364D mutant, which does not interact stably with Cdc55p, are not temperature-sensitive. Furthermore, both Δ PPM1 and Δ PPM1Δ PPM2 strains displayed no temperature-sensitive phenotype even though Pph21p association with Cdc55p could not be detected.4 The simplest explanation for these data is that in T364D and strains deleted for PPM1, some residual Cdc55p and Rts1p binding occurs that is sufficient to prevent the temperature-sensitive phenotype but cannot be detected by our assay.

The PP2A residues threonine 364 and tyrosine 367 are completely conserved in all organisms, suggesting that they have important functions. In both yeast and mammalian cells (10), substitution of a negatively charged amino acid for either of these residues abolishes Cdc55p (B subunit) binding, whereas conservative substitution with alanine or phenylalanine, respectively, does not. Moreover, we have shown in the present study that acidic substitution of these residues leads to a defect in PP2A function as assayed by nocodazole sensitivity. Together, these results suggest that phosphorylation of these residues might regulate B subunit-directed PP2A functions by dissociating Cdc55p (B subunit) or by modulating PP2A activity directly (16). Although we have not been able to detect threonine or tyrosine phosphorylation of yeast C subunits using either phosphoamino acid-specific antibodies or radiolabeling,4 it is possible that these modifications are transient and triggered by specific signals, as appears to be the case for tyrosine phosphorylation of mammalian C subunit (42).

The results of our findings suggest that the PP2A methyltransferase could be an attractive chemotherapeutic drug target for viruses such as human immunodeficiency virus that target trimeric PP2A via the B subunit. Recently, E. Cohen and co-workers (43) demonstrated that the human immunodeficiency virus Vpr protein associates with PP2A via the B subunit (43). Furthermore, they showed that this association is important for the cell cycle arrest function of Vpr. Drugs or other approaches that inhibit PMT1 or decrease its expression could have the net effect of interfering with human immunodeficiency Vpr function and result in decreased human immunodeficiency virus titers in AIDS patients (44, 45).

Acknowledgments

We thank Monica McQuoid, Matthew Stark, Amanda Bauman, and Marie Kozel for excellent technical assistance, J. Ariño, A. Rudner, R. Hallberg, and A. Murray for sending reagents, and Karma Carrier for critical reading of the manuscript. Under agreements between Upstate Biotechnology Inc. and Emory University and Calbiochem and Emory University, David Pallas is entitled to a share of sales royalty received by the University from these companies. In addition, this same author serves as a consultant to Upstate Biotechnology Inc. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; C subunit, catalytic subunit; HA, hemagglutinin; PMT1, protein methyltransferase-1 (mammalian); wt, wild type; Vpr, virion-associated accessory protein; YPD, yeast extract/peptone/dextrose.

X. X. Yu, X. Du, C. S. Moreno, R. E. Green, E. Ogris, Q. Feng, L. Chou, M. J. McQuoid, and D. C. Pallas, Mol. Biol. Cell 12, in press.

E. Ogris, H. Wei, and D. C. Pallas, unpublished data.

H. Wei and D. C. Pallas, unpublished data.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA57327 (to D. C. P.).

References

- 1.Cohen P. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:453–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mumby MC, Walter G. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:673– 699. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopkin K. J Natl Inst Health Res. 1995;7:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Usui H, Imazu M, Maeta K, Tsukamoto H, Azuma K, Takeda M. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3752–3761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cegielska A, Shaffer S, Derua R, Goris J, Virshup DM. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4616– 4623. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamibayashi C, Estes R, Lickteig RL, Yang SI, Craft C, Mumby MC. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20139–20148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer-Jaekel RE, Ohkura H, Ferrigno P, Andjelkovic N, Shiomi K, Uemura T, Glover DM, Hemmings BA. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:2609–2618. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.9.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang SI, Lickteig RL, Estes R, Rundell K, Walter G, Mumby MC. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1988–1995. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cayla X, Ballmer-Hofer K, Merlevede W, Goris J. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogris E, Gibson DM, Pallas DC. Oncogene. 1997;15:911–917. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno CS, Park S, Nelson K, Ashby DG, Hubalek F, Lane WS, Pallas DC. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5257–5263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sontag E, Nunbhakdi-Craig V, Bloom GS, Mumby MC. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1131–1144. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCright B, Rivers AM, Audlin S, Virshup DM. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22081–22089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griswold-Prenner I, Kamibayashi C, Maruoka EM, Mumby MC, Derynck R. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6595– 6604. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turowski P, Myles T, Hemmings BA, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1997–2015. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.6.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Martin BL, Brautigan DL. Science. 1992;257:1261–1264. doi: 10.1126/science.1325671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo H, Damuni Z. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2500–2504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rundell K. J Virol. 1987;61:1240–1243. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.1240-1243.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M, Damuni Z. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;202:1023–1030. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Favre B, Zolnierowicz S, Turowski P, Hemmings BA. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16311–16317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J, Stock J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19192–19195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie H, Clarke S. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1981–1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Baere I, Derua R, Janssens V, Van Hoof C, Waelkens E, Merlevede W, Goris J. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16539–16547. doi: 10.1021/bi991646a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kowluru A, Seavey SE, Rabaglia ME, Nesher R, Metz SA. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2315–2323. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.6.8641181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turowski P, Fernandez A, Favre B, Lamb NJ, Hemmings BA. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:397– 410. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogris E, Du X, Nelson KC, Mak EK, Yu XX, Lane WS, Pallas DC. J Biol Chem. 1999a;274:14382–14391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sneddon AA, Cohen PT, Stark MJ. EMBO J. 1990;9:4339– 4346. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Zyl W, Huang W, Sneddon AA, Stark M, Camier S, Werner M, Marck C, Sentenac A, Broach JR. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4946– 4959. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.11.4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ronne H, Carlberg M, Hu GZ, Nehlin JO. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4876– 4884. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Healy AM, Zolnierowicz S, Stapleton AE, Goebl M, DePaoli-Roach AA, Pringle JR. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5767–5780. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shu Y, Yang H, Hallberg E, Hallberg R. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3242–3253. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minshull J, Straight A, Rudner AD, Dernburg AF, Belmont A, Murray AW. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1609–1620. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70784-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Burke DJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:620– 626. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell KS, Auger KR, Hemmings BA, Roberts TM, Pallas DC. J Virol. 1995;69:3721–3728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3721-3728.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlenstedt G, Saavedra C, Loeb JD, Cole CN, Silver PA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:225–229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shu Y, Hallberg RL. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5618–5626. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams A, Gottschling DE, Kaiser CA, Stearns T. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton A, Immanuel D, Arndt KT. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2133–2148. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J, Chen Y, Tolstykh T, Stock J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6043– 6047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruediger R, Van Wart Hood JE, Mumby M, Walter G. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4282– 4285. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen J, Parsons S, Brautigan DL. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7957–7962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hrimech M, Yao XJ, Branton PE, Cohen EA. EMBO J. 2000;19:3956–3967. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44.Ayyavoo V, Mahalingam S, Rafaeli Y, Kudchodkar S, Chang D, Nagashunmugam T, Williams WV, Weiner DB. J Leukocyte Biol. 1997;62:93–99. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masuda M, Nagai Y, Oshima N, Tanaka K, Murakami H, Igarashi H, Okayama H. J Virol. 2000;74:2636–2646. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2636-2646.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clotet J, Posas F, Hu GZ, Ronne H, Arino J. Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]