Abstract

Objectives. To develop and implement a seminar course for graduate students in the social and administrative pharmaceutical sciences to enhance knowledge and confidence with respect their abilities to demonstrate appropriate business etiquette.

Design. A 1-credit graduate seminar course was designed based on learner-centered constructivist theory and application of Fink’s Taxonomy for Significant Learning.

Assessment. Eleven students participated in the spring 2011 seminar course presentations and activities. Students completed pre- and post-assessment instruments, which included knowledge and attitudinal questions. Formative and summative assessments showed gains in student knowledge, perceived skills, and confidence based on observation and student-reported outcomes.

Conclusion. Graduate student reaction to the course was overwhelmingly positive. The etiquette course has potential application in doctor of pharmacy education, other graduate disciplines, undergraduate education, and continuing professional development.

Keywords: seminar, graduate education, educational theory, professionalism, business etiquette

INTRODUCTION

Civility (accepted social behaviors) is a foundational component of the complex phenomenon of professionalism.1 In global business and healthcare environments and with the diversity in American society, professional and graduate pharmacy students may interact routinely with individuals from other cultures. In professional relationships, undesired outcomes may arise from etiquette gaffes, such as ineffective or potentially offensive interpersonal communications between people of different age groups, professional positions, races, ethnicities, nationalities, and belief systems. To avoid these communication problems, students need to be knowledgeable about and aware of business etiquette.2 Knowledge and application of appropriate business etiquette will help students and graduates feel more confident in workplace environments, which will likely translate into more successful business and/or healthcare outcomes.

In pharmacy education, instruction on aspects of professionalism and professional socialization is requisite.1,3 Student development of professionalism is emphasized in Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards and guidelines, which also include curricular strategies for achieving this goal. Performance competencies include appropriate professional behavior and self-awareness.4 The Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) educational outcomes for pharmacy students state the need for appropriate professional demeanor as well as effective communications in consideration of contextual and cultural factors.5 Instruction on social, interpersonal skills, and etiquette is considered essential in academic disciplines other than doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) curricula, 3,6 including graduate pharmaceutical sciences (ie, master of science degree or doctor of philosophy degree),7 medicine,8 law,9 business,10-12 and others. Descriptions of effective pedagogical strategies to teach business etiquette to students are lacking in the literature. Colleges and schools of pharmacy and/or their universities may provide students with, for example, a mini-workshop (eg, 2 hours or less) on aspects of business etiquette within a professional or career development series.13 Etiquette 101-type dinners or luncheons are popular among college students.14 However, little guidance is available for developing an intellectual, multidimensional, academic course on business etiquette.

This article describes the conceptualization, implementation, and assessment of an innovative graduate seminar course on business etiquette for students in the social and administrative pharmaceutical sciences. This was a different type of seminar, created and developed in response to a recognized need among graduate students for instruction on knowledge and skills in business etiquette. The impetus for the course was to address this deficit, increase knowledge, skills, and confidence; and inspire continued learning. The idea emanated from the observation that graduate students in the social and administrative pharmacy sciences, both domestic and international, are inadequately knowledgeable about and unfamiliar with customary business etiquette practices. For example, some students feel awkward taking the initiative to approach someone new, introduce themselves, and strike up a conversation, and, as appropriate, engage in a handshake. Even students without such reticence may not know the appropriate situational considerations in introductions and guidelines for social interaction. Another example reported by pharmacy school faculty is that the tone of some student e-mails and other written communication received from students is unprofessional, emphasizing the need for improved knowledge of etiquette in such business communications.6 The new era of distance learning and e-professionalism (ie, online reflection of professional attitudes and behaviors as expressed through use of digital media, including e-mail communication, social media, and other Web-based information shaping the individual’s online persona)6,15,16 support the need to revisit instruction in the principles of business etiquette. Additionally, while graduate students in the pharmaceutical sciences have strong backgrounds in their respective scientific fields, they generally are not instructed in professional roles beyond academic integrity. Regardless of academic discipline, graduate students would benefit from instruction on etiquette and decorum as part of disciplinary socialization. An American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) section subcommittee in the social and administrative pharmaceutical sciences noted a need for instruction in the “Etiquette of Teaching” but acknowledged obstacles to their attempts to determine what components to include when preparing graduate students for teaching roles.17

DESIGN

The required seminar is used by the Department of Pharmacy Administration at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) to enhance graduate student knowledge, skills, and performance. Graduate seminar course coordination rotates among faculty members each semester during the academic year. Eleven graduate students enrolled in the seminar course during spring semester 2011. Through exempt review by the UIC institutional review board, approval was granted to describe the instructional techniques and assessment results for the graduate seminar course on business etiquette. Course goals were to: develop, implement, and evaluate a seminar course in business etiquette for graduate students in the social and administrative pharmaceutical sciences; assess whether graduate students’ knowledge, perceived skills, and confidence in business etiquette increased upon completion of the course; and inspire students to build knowledge and skills, within and outside the classroom.

Whether through professor-led or student-based discussion formats,18 the graduate seminar course is an intellectual forum wherein students construct knowledge and make meaningful connections of information gleaned from discrete, specialized curricular aspects or other substantive areas within the discipline.19 The interactive, facilitative nature of this graduate seminar in business etiquette was informed by the educational philosophy of constructivism. Constructivist theory states that an effective learning approach for professional development should include student-focused, action-based strategies to build upon new knowledge and prior knowledge and experiences.9,19 Effective teaching under the constructivist approach enables the learner to interact with peers in acquiring new information and reframing experiences, which helps students apply critical thinking to understand and interpret newly acquired knowledge, improve their problem-solving abilities, and self-reflect on the information in a manner that has unique meaning for each individual.9 Under this educational theory, group-based, hands-on activities are considered a hallmark in heightening student engagement and learning. Through discussions and activities, students observe and learn from others with diverse backgrounds and varied perspectives, helping them build upon their own knowledge base and self-awareness. Use of this learning process should help students increase their knowledge and skills through individual thought, collaborative problem solving, skills development, increased appreciation for diversity, and a foundation for lifelong learning.

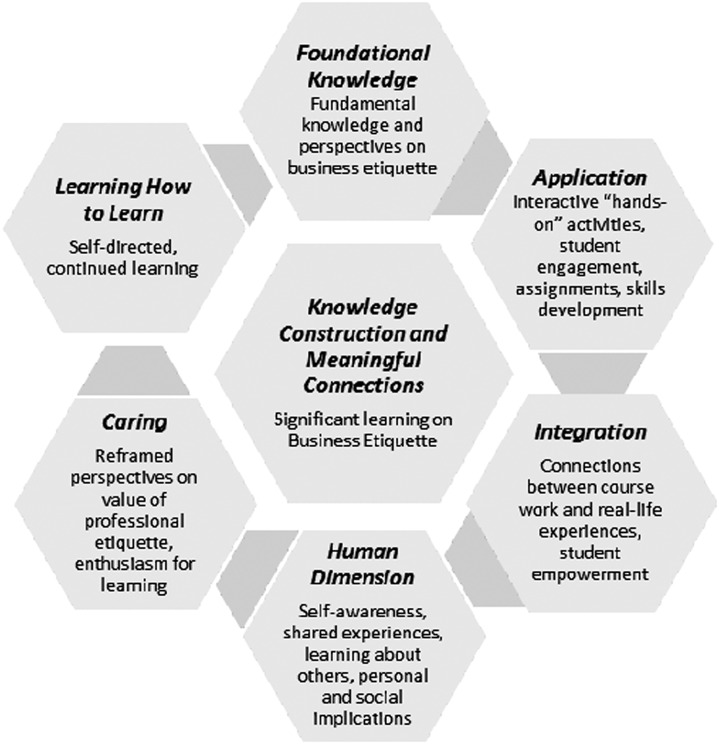

In the process of achieving scholarly and meaningful learning, salient knowledge should be retained after course completion. Students should apply knowledge gained to novel experiences, be able to think more critically and solve problems, and engage in self-motivation to learn. These educational goals are rooted in Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning, which served as a template in the course design.20 The described constructivist, learner-centered approach for the graduate seminar course design is depicted in the adaptation of Fink’s Taxonomy shown in Figure 1. Categories of learning within the taxonomy are intended to be relational and interactive to help achieve significant learning, ie, learning that produces lasting changes that are important to each student.20

Figure 1.

Adaptation of Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning20 to Course Design for Graduate Seminar on Business Etiquette

The 1-credit-hour departmental graduate seminar was graded on a satisfactory or unsatisfactory basis. To receive a satisfactory grade, graduate students were expected to attend class and actively participate in class activities and discussions, deliver a well-organized seminar presentation on the assigned date, provide supporting materials for the audience, and complete assignments. The duration of the graduate seminar course was January through May 2011. With the exception of the last class session on business dining etiquette (planned for 2 hours), each weekly seminar session was planned for one 50-minute class period. Class sessions included presentations led by the faculty course coordinator or graduate students. For 3 seminar sessions, student presenters were allowed to work in pairs to accommodate scheduling needs. Presentations were expected to include knowledge delivery and at least 1 application of the business etiquette rule(s) or guide(s), either as an in-class, preclass, or after-class activity. Students were required to meet with the course coordinator at least 2 business days prior to their presentations to provide a general overview of presentation, share drafts of presentation materials, and state plans to facilitate active audience discussion and participation.

When planning and preparing for the seminar series on business etiquette, the course coordinator established a small reference library.21-27 In addition to scholarly articles and books, credible Internet references, and other resources identified by graduate students, students were welcomed to borrow any of these texts in preparation for their presentations. To benefit classmates, a graduate student donated an additional reference from his personal collection to the course library.28

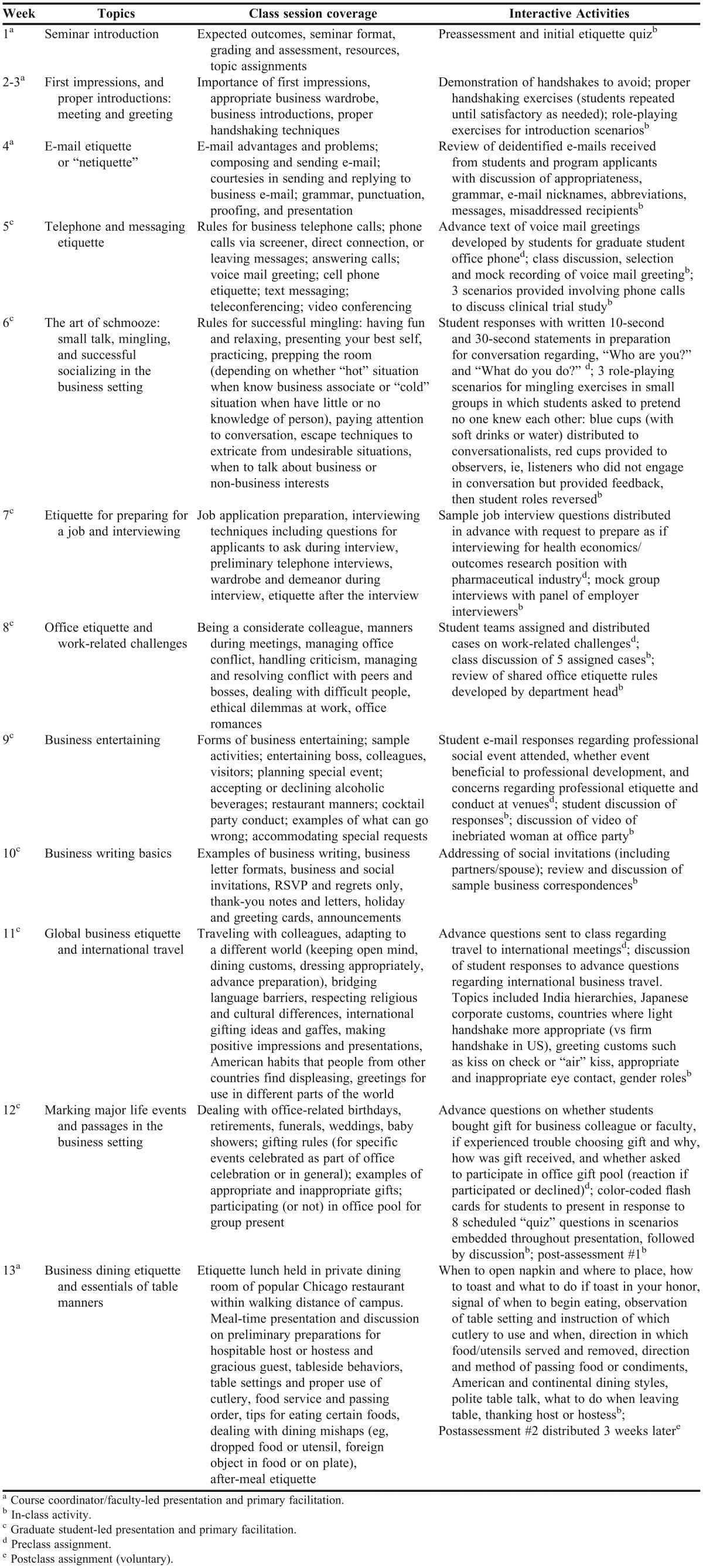

Seminar topics, class overview and description, and interactive activities are summarized in Table 1, which also shows which classes were led by the faculty member or students, and associated class activities. Each class was designed to synthesize and build upon previous knowledge to deepen understanding. For example, restaurant manners for hosts and guests were briefly mentioned during the week 9 talk on business entertaining. This topic was expanded during the week 13 seminar on dining etiquette. When a slide on simple socializing was shown at the same business entertaining class presentation, the student presenter reminded the group about knowledge learned from the week 6 class on schmoozing, small talk, mingling, and successful socializing. In the schmoozing class, the preactivity involved student consideration of clear and concise messages (a 10-second and 30-second response) about themselves. These included messages regarding their position, background, and/or personal history, which the students wanted to share in a business situation, and about their work to introduce their research in a manner compatible with a knowledgeable but not expert audience. The take-home message was that statements that are short and comprehensible are more likely to result in a conversation that flows back-and-forth between persons in social business settings.

Table 1.

Business Etiquette Seminar Topics, Description, and Activities

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Direct evidence of student learning for foundational knowledge and application categories in Fink’s Taxonomy was demonstrated through observation of draft and final student presentations, assignment/activity development exercises by student presenters and completion by student peers, level of class discussions, student engagement, and final satisfactory course grades. Questions, answers, and suggestions for improvement were offered by the instructor as a formative assessment during a sit-down meeting in advance of the student presentations. Suggestions were offered on student drafts and plans to achieve instructional objectives within the allotted time. Each student or student team provided a creative, high-quality presentation, as shown through content and peer engagement.

The business etiquette seminar seemed to strike a chord with the students. Outside class, students practiced etiquette skills among themselves, with their friends and others in their social circles, and in professional venues. From Fink’s Taxonomy, this demonstrated integration with real-world experiences; human dimension with self-awareness, shared experiences, and social implications; caring with enthusiasm for learning and new values on the importance of etiquette; and self-directed learning. Students shared their experiences in the classroom, which helped build new knowledge under constructivist theory and in accord with the taxonomy. For example, a student stated how she took the initiative to extend her hand and introduce herself to many colleagues at a business social event. She would not have felt comfortable initiating this type of contact prior to the course, as this activity is not the norm in her culture. Many students were so enthused that they commented they may be “overdoing it” because they continually practiced by introducing themselves to each other repeatedly when passing in the hallways. In informal gatherings, they also offered to shake hands with their friends who gave them quizzical looks until the reason for this behavior was explained.

From Fink’s Taxonomy, a desired outcome is that students “Learn How to Learn,” which our students displayed throughout the semester. Students took it upon themselves to disseminate information to fellow students and the instructor about upcoming campus events (eg, workshops offered by the UIC Office of Career Services). These campus-sponsored events included etiquette tips for international students, job interviewing, business etiquette in the United States, resume and cover letter writing for US employers, and an interactive workshop entitled, “The One-Minute Academic Introduction.” Another example of student engagement was the sharing of etiquette-themed articles published in the Wall Street Journal in January 201129,30 that would be useful in seminar preparation and discussions. Students also routinely searched Web sites for interesting information on seminar topics.

In almost every session, students desired and chose to stay beyond the regular seminar class time (after class was dismissed), continuing to practice exercises and activities. This was the norm rather than the exception, with the majority of students staying 20-30 minutes beyond the 50-minute class time. On a couple of occasions, when the course coordinator left because of other commitments, the graduate students remained and kept working.

Pre- and post-assessments were conducted with enrolled graduate students (n=11) as 1 measure to determine effectiveness of the instructional techniques (Appendix 1). The preassessment instrument, which was administered during the first class of the semester, included 25 items on etiquette knowledge. Questions were adapted from Internet and text examples and were asked in a multiple-choice format. Unlike the in-depth review, integrated explanations, and cultural norms provided during subsequent presentations, the knowledge pretest questions were based on quick etiquette tips. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Scores indicated substantial room for improvement, with the percentage of correct answers ranging from 48% to 72%, with a mean score of 61.8 ± 7.0 (SD). The preassessment also included items to measure student confidence on knowledge and skills. When asked on the preassessment instrument, “How confident are you regarding your knowledge of business etiquette?,” no one responded “very confident.” Four students (36.4%) indicated they were confident, and 7 (63.6%) stated they were not confident. The same responses were given to the question, “How confident are you regarding your business etiquette skills?”

An alternate postassessment instrument was administered near the end of class at week 12. Eight items for the 16-item etiquette quiz administered on that date were repeated from the pretest, with the remaining being new items including 2 open-ended questions. A set of additional voluntary postassessment questions was sent to students 3 weeks after the seminar series concluded, after all students had received their course grades. This included 2 additional etiquette quiz items relating to the class on business dining etiquette during week 13, for a total of 18 knowledge items during the postassessments, in addition to follow-up items on confidence in etiquette abilities and other summary attitudinal items regarding the seminar course. Students were entrusted with honoring the request not to look up answers to the last 2 etiquette quiz items before submitting their assessments. The response rate was 100% for all assessment items.

Students’ performance was higher for the etiquette quiz items on the postassessment instrument from paired t test (p < 0.001); student scores ranged from 61.1% to 100% with a mean score of 82.8 ± 13.0. Even with the gain, scores were not extremely high on average, with only 2 scoring higher than 90%, indicating a need for continued reinforcement of the more detailed etiquette guidelines. In retrospect, some of the questions on etiquette tips were trivial, considering the synthesized learning process and emphasis on significant, meaningful learning in the graduate seminar course. Further, appropriate etiquette may be situational; that is, what is considered appropriate for a given interaction may be influenced by setting (private or public) as well as cultural norms. More meaningful learning occurred as a result of student awareness of the need to be informed about salient aspects of business etiquette and aware of etiquette considerations when preparing for different business situations.

Based on the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, students demonstrated more confidence in their knowledge (p=0.005) and skills (p=0.003) by the end of the seminar course. When asked during the postassessment, “How confident are you regarding your knowledge of business etiquette?” 4 students (36.4%) responded “very confident” (none had stated so in the pretest) and 7 (63.6%) responded “confident.” In skills, postassessment results revealed that 3 (27.3%) students were very confident, 7 (63.6%) were confident, and 1 (9.1%) remained not confident. Several who indicated on the postassessment that they were confident indicated in the open-ended section a desire to practice more.

All students responded that the required premeeting with the course coordinator in advance of seminar presentation was “very helpful.” When asked how helpful they found the available reference books, 10 (90.9%) said “very helpful” and 1 said “helpful.” In the postassessment, graduate students were asked to describe any situation in which they had used something learned in the etiquette seminar. Students stated that they had used knowledge and skills from the seminar in situations outside the classroom, such as in off-campus research meetings, at business dinner functions, during job interviews, and in introductions to national and international corporate executives. In the postassessment, graduate students were given the opportunity to provide any additional comments regarding this seminar. Responses were universally positive. Students noted appreciation for what they had learned but also expressed a need for more instruction and practical application of their skills.

DISCUSSION

Graduate students were excited when first informed of the planned theme on business etiquette during the last week of classes in fall semester 2010. From day 1, the department head was extremely supportive of the seminar topics, frequently inquired how the course was going, and shared positive feedback he had heard from students. The final seminar on dining etiquette, which was conducted in the private dining room of a local restaurant near campus, was hosted and sponsored by the department head. Initial reaction from faculty colleagues was mixed, but they quickly developed a more positive perspective. When the seminar theme was first announced, some departmental colleagues snickered and stated that the seminar series would be akin to “Miss Manners.” By the first week of class, however, the same faculty members expressed curiosity about the seminar coverage and began offering ongoing suggestions for topic inclusion, including personal hygiene, business writing, and e-mail decorum. Faculty opinion likely transitioned positively as the result of frequently expressed student excitement, topic descriptions by the course coordinator, their own observations of needed etiquette instruction, and department head encouragement. Along with the students, the course instructor also learned a great deal about business etiquette, and departmental colleagues engaged in more frequent discussions about concepts of professional decorum with a heightened awareness of and appreciation for the subject. Aspects of salient learning appeared to be significant and meaningful to students, as they indicated areas in which some lasting changes were developed. Becoming proficient in business etiquette, however, requires sustained reinforcement and application. Aspects of the seminar course could be incorporated in continuing professional development for pharmacy faculty and practitioners.

The constructivist, learner-centered approach resonated with graduate students because they desired and needed a way to gain knowledge about and prepare for real-world experiences.9 The hands-on approach worked well, and students seemed to embrace personal responsibility for their own knowledge. Our graduate students showed responsibility in completing assignments and working with others (eg, when classmates asked for them to reply quickly to a survey), respecting others, and accepting constructive criticism. Graduate students come from diverse backgrounds, including some for whom English is a second language. Faculty members should keep in mind the need to introduce cultural norms of American society that may be unfamiliar to international students. However, regardless of nationality, each generational cohort of students brings its own culture; thus, review of professional expectations is appropriate.

Aspects of this graduate seminar course can be applied in whole or in part for PharmD programs, other graduate program disciplines, and undergraduate courses. When offered again, this course will likely be made available as an elective with dual credit (ie, both PharmD and graduate students in the pharmaceutical sciences could enroll, as space allows). Journaling for self-reflection may be included as part of the assignments in future offerings of the course. During the inaugural offering, such information was provided extemporaneously from students’ enthusiastic self-discovery.

For other colleges and schools that may use aspects of this described seminar course, interactive hands-on activities are recommended, based on our students’ favorable response. Hands-on activities seem well-suited for seminar or elective courses with limited class sizes, such as this etiquette course. The learning strategies used in this seminar may not work in large lecture classes unless they include smaller recitation sections or some equivalent thereof. In those cases, a higher number of instructors may be needed to observe interactive activities among student learners. The format may or may not work with distance education, depending on visual conferencing capabilities and the nature of the applied activities. Most aspects of the current course were successful. It seems, however, that more time per class – perhaps 90 minutes - should have been allotted. Future classes will devote more time to the development of better knowledge-assessment measures.

The seminar could be applicable to other graduate students in the pharmaceutical sciences as an elective or required course, but some of the example applications would need to be substituted with applications more relevant to the academic discipline. For example, there is a need for etiquette specific to research laboratories, whereas other topics, such as preparing for job interviews and successful social networking and interactions, are universal. The course could also be adapted for use by colleagues engaged in undergraduate education. When the course syllabus was shared with a faculty colleague in the UIC Department of Communication, she noted that undergraduate students would also find an etiquette seminar useful and interesting, as it cuts across many disciplines and addresses issues beyond etiquette skills. Issues of identity, language, messages, social roles and relationships, and impression management, among others, were central to the etiquette seminar course. However, at its core, etiquette is a facet of civility, which has broad application in that it addresses the fundamental nature of how people interact with each other.

SUMMARY

This article describes a theoretically constructed pedagogical activity of interactive student learning in a course on business etiquette. Based on classroom assessments and other comments received, students developed meaningful learning and seemed to enjoy the novel and practical seminar course. The graduate course on business etiquette increased knowledge, instilled more confidence among students, and has potential applicability in graduate, professional, and undergraduate education, as well as continuing professional development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author expresses sincere gratitude to Nicholas G. Popovich, PhD, Professor and Head, UIC Department of Pharmacy Administration, for his enthusiastic support of the seminar theme, helpful suggestions, and sponsorship of the business etiquette luncheon.

Appendix 1. Description of Assessment Instruments Used in Business Etiquette Seminar Course

Attitudinal items: In both the pre- and post-assessment, graduate students were asked the following 2 questions, with response choices of “very confident,” “confident,” or “not very confident”:

• How confident are you regarding your knowledge of business etiquette?

• How confident are you regarding your business etiquette skills?

The postassessment included the following 2 items, with response choices of “very helpful,” “helpful,” and “not very helpful”:

• How helpful were the reference books made available to the class?

• How helpful was the required premeeting, in advance of your seminar presentation, with the course coordinator?

The postassessment included an open-ended question asking students to describe any situation in which they used something learned from the etiquette seminar, as well as an open item for any additional comments regarding this seminar.

Knowledge items: 25 items were included on the etiquette knowledge quiz in the preassessment. The postassessment instruments were comprised of 18 knowledge items, including 8 repeated from the preassessment. All items in the preassessment were in multiple-choice format (2, 3, or 4 response options); 16 etiquette quiz items in the posttest were multiple-choice format and 2 required open-ended responses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hammer DP. Civility and professionalism. J Pharm Teach. 2002;9(3):71–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mausehund J, Dortch RN, Brown P, Bridges C. Business etiquette: what your students don't know. Bus Comm Q. 1995;58(4):34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3) Article 96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Adopted Jan 15, 2006 (Guidelines Verson 2.0 Adopted Jan 23, 2011). https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Social and Administrative Sciences Supplemental Educational Outcomes Based on CAPE 2004. 2007 http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Documents/SocialandAdminDEC06.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foral PA, Turner PD, Monaghan MS, et al. Faculty and student expectations and perceptions of e-mail communication in a campus and distance doctor of pharmacy program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10) doi: 10.5688/aj7410191. Article 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surratt CK. Creation of a graduate oral/written communication skills course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(1) doi: 10.5688/aj700105. Article 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn MW. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988–1989. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0801863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willey L, Burke DD. A constructivist approach to business ethics: developing a student code of professional conduct. J Legal Stud Educ. 2011;28(1):1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley CA, Bridges C. Introducing professionalism and career development skills in the marketing curriculum. J Market Educ. 2005;27(3):212–218. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovett M, Jones IS. Social/interpersonal skills in business: in field, curriculum and student perspectives. J Manage Market Res. 2008;1(Dec):1–13. http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/08063.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaffer BF, Kelley CA, Goette M. Education in business etiquette: attitudes of marketing professionals. J Educ Bus. 1993;68(6):330–333. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ference JD, Medina MS. Modifying a traditional course for the PharmD curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5) Article 122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogg P. Etiquette 101. Chron Higher Ed. 2006;52(31):A64. http://chronicle.com/article/Etiquette-101/23138/. Accessed August 29, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cain J, Romanelli F. E-professionalism: a new paradigm for a digital age. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2009;1(2):66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangan K. Etiquette for the bar. Chron Higher Ed. 2007;53(19):A31. http://chronicle.com/article/Etiquette-for-the-Bar/14858/. Accessed August 29, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Academic Careers Subcommittee 2006-2007, Barner JC, Droege M, Holmes E, Miller L, Young H. Graduate student teaching skills preparation. http://www.aacp.org/resources/student/graduateresearchstudents/Documents/GraduateStudentTeachingSkillsPreparation.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2012.

- 18.Steen S, Bader C, Kubrin C. Rethinking the graduate seminar. Teach Sociol. 1999;27(2):167–173. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammett R, Collins A. Knowledge construction and dissemination in graduate education. Can J Educ. 2002;27(4):439–453. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fink LD. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Axtell RE, editor. Do's and Taboos Around the World, 3rd ed. White Plains, NY.: The Benjamin Company, Inc.; 1993. Compiled by the Parker Pen Company. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldrige L. Letitia Baldrige’s New Complete Guide to Executive Manners. New York: Rawson Associates; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casperson DM. Power Etiquette: What You Don’t Know Can Kill Your Career. New York: American Management Association International; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox S. Business Etiquette for Dummies, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langford B. The Etiquette Edge: The Unspoken Rules for Business Success. New York: American Management Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pachter B, Magee S. When the Little Things Count … And They Always Count: 601 Essential Things That Everyone in Business Needs to Know. Cambridge, MA: De Capo Press Lifelong Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitmore J. Business Class: Etiquette Essentials for Success at Work. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinet J. The Art of Mingling: Proven Techniques for Mastering Any Room. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverman RE. How to navigate a business meal [blog post] The Juggle. Wall Street Journal Web site. Jan 27, 2011. http://blogs.wsj.com/juggle/2011/01/27/how-to-navigate-a-business-meal/?blog_id=13&post_id=14123. Accessed August 29, 2012.

- 30.Glazer E. Social rules at work. Wall Street Journal. Web site. Jan 15, 2011. http://online.wsj.com/article_email/SB10001424052748704323204576084533501183902-lMyQjAxMTAxMDIwODEyNDgyWj.html. Accessed August 29, 2012. [Google Scholar]