Abstract

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act proposes strategies to address the workforce shortages of primary care practitioners in rural America. This review addresses the question, “What specialized education and training are colleges and schools of pharmacy providing for graduates who wish to enter pharmacy practice in rural health?” All colleges and schools accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education or those in precandidate status as of December 2011 were included in an Internet-based review of Web sites. A wide scope of curricular offerings were found, ranging from no description of courses or experiences in a rural setting to formally developed programs in rural pharmacy. Although the number of pharmacy colleges and schools providing either elective or required courses in rural health is encouraging, more education and training with this focus are needed to help overcome the unmet need for quality pharmacy care for rural populations.

Keywords: rural health, pharmacy curriculum, underserved, experiential

INTRODUCTION

Many states are faced with the dilemma of an inequitable distribution of primary care workers, including pharmacists. The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) included provisions to minimize disparities in access to primary care. A principle focus of the PPACA is the promotion and expansion of the primary care workforce.1 Although many of the strategies outlined in the act focus on medical trainees, the PPACA does not exclude other health disciplines; in fact, it recognizes the expanding role of clinical pharmacists to address the severe nationwide deficiencies related to medication use. The PPACA provides for medication therapy management (MTM) grant programs, Medicare Advantage Plan incentives, integrated-care models, and transitional care activities that are specific to clinical pharmacy services.2

While 90% of the United States land mass is defined as rural and 20% of Americans live in rural areas, only 12% of pharmacists practice in rural locations.3,4 Considering these statistics, the provisions of the PPACA, and potential changes in healthcare reform on the horizon, there is an unquestionable need to address the shortage of pharmacists in rural or underserved areas. This well-documented need leads to the question, “Are colleges and schools of pharmacy delivering coursework to prepare graduates to provide primary care services in rural areas?”1-7

A review of the literature reflected a deficit in studies related to rural health pharmacy education in the United States. Notably, the Journal published the recommendations of a task force convened by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy and the Pharmaceutical Services Support Center in 2008. This task force was charged with developing a curricular framework to engage pharmacy colleges and schools in educating students to care for the underserved. In this framework, the care of patients in rural areas was mentioned but not emphasized. Information specific to existing educational programs has been published about programs located outside of the United States, particularly those in Australia.8,9 While there are many articles on pharmacy education and practice in rural Australia, a goal of this review was to focus on the government-based policies and educational initiatives affecting the delivery of health care for rural citizens of the United States. Multiple published studies pertaining to rural health education in the United States relate to service-learning components of elective practice experiences, telepharmacy, and the incorporation of public health into pharmacy education, but no comprehensive review of curricular offerings in rural health pharmacy has been published.10-14 The purpose of this paper is to provide the status of curricular offerings in rural health pharmacy education and training at colleges and schools of pharmacy in the United States.

METHODOLOGY

In conducting this review of curricula, a thorough search was undertaken of each US college or school of pharmacy listed as accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE).15 The primary investigator conducted an initial search of all Web sites and separated the institutions into 2 categories: those with and those without rural curricular offerings. One of 2 independent reviewers verified all information related to the colleges and schools identified as having rural curricular offerings. The independent reviewers also reexamined 30% of colleges and schools determined not to have rural curricular offerings. The colleges and schools that underwent this second check were determined using a random number generator, and the 39 schools not included in this review were reanalyzed by the independent reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by the 2 independent reviewers first and then rectified with the primary investigator. All investigators followed the same procedure when searching Web sites.

Two different approaches were taken for searching the Web sites of each college and school of pharmacy. The first was to use an intranet search of the Web sites using the following search terms: “rural,” “rural pharmacy,” “rural experience,” “rural rotation,” “rural health,” and “rural health curriculum.” The second approach was to search individual pages within the Web site, including those related to experiential program, experiential education, PharmD curriculum, current students, prospective students, pharmacy practice department (to review for faculty members placed in rural practice sites), practice experiences, links to descriptions of introductory and advanced pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs and APPEs, respectively), and any additional pages linked within these topics that pertained to experiential or classroom teaching. Pages were not excluded based on format. Each page was inspected for information related to rural health training available to student pharmacists at that institution. Any information pertaining to rural health curricular developments was recorded. When a curricular experience in rural health was identified within a single institution’s Web site yet needed some clarification, an e-mail message was sent to a faculty member involved with the rural health initiative. Otherwise, no additional telephone or e-mail follow-up was conducted with colleges and schools of pharmacy, as the intent of this review was to determine the curricular offerings pertaining to rural health as presented on the institutions’ Web sites. Information was excluded from the summative analysis below if a Web site provided only a single reference to programs or studies but no description of programs, courses, or other opportunities was available online. Each Web site search took between 20 and 45 minutes, depending on Web site design and size and number of links available.

If research within a college’s or school’s Web site revealed a course or courses, practice experience, or other opportunities with a focus on rural health, that institution’s intervention was included in this review. However, if a college’s or school’s mission statement mentioned the term “rural” yet provided no specified or focused coursework in rural health on its Web site, the program was not included in this review.

RURAL HEALTH PROGRAMS IN PHARMACY EDUCATION

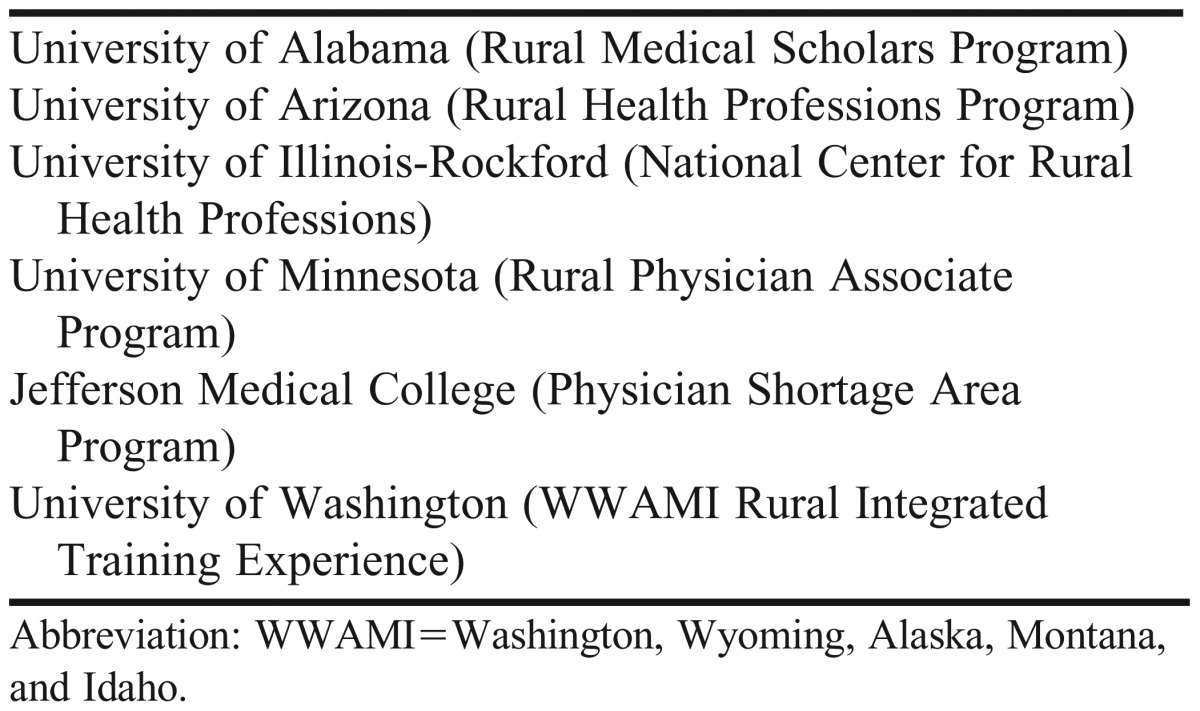

The review of literature and Web sites yielded a number of institutions offering a rural health focus for medical students, and some pharmacy colleges and schools that have been able to develop their programs based on the success of a partnering medical school. Table 1 lists medical school-based programs that have provided a rural health focus for students.

Table 1.

Medical Schools Offering Rural Health-Focused Programs

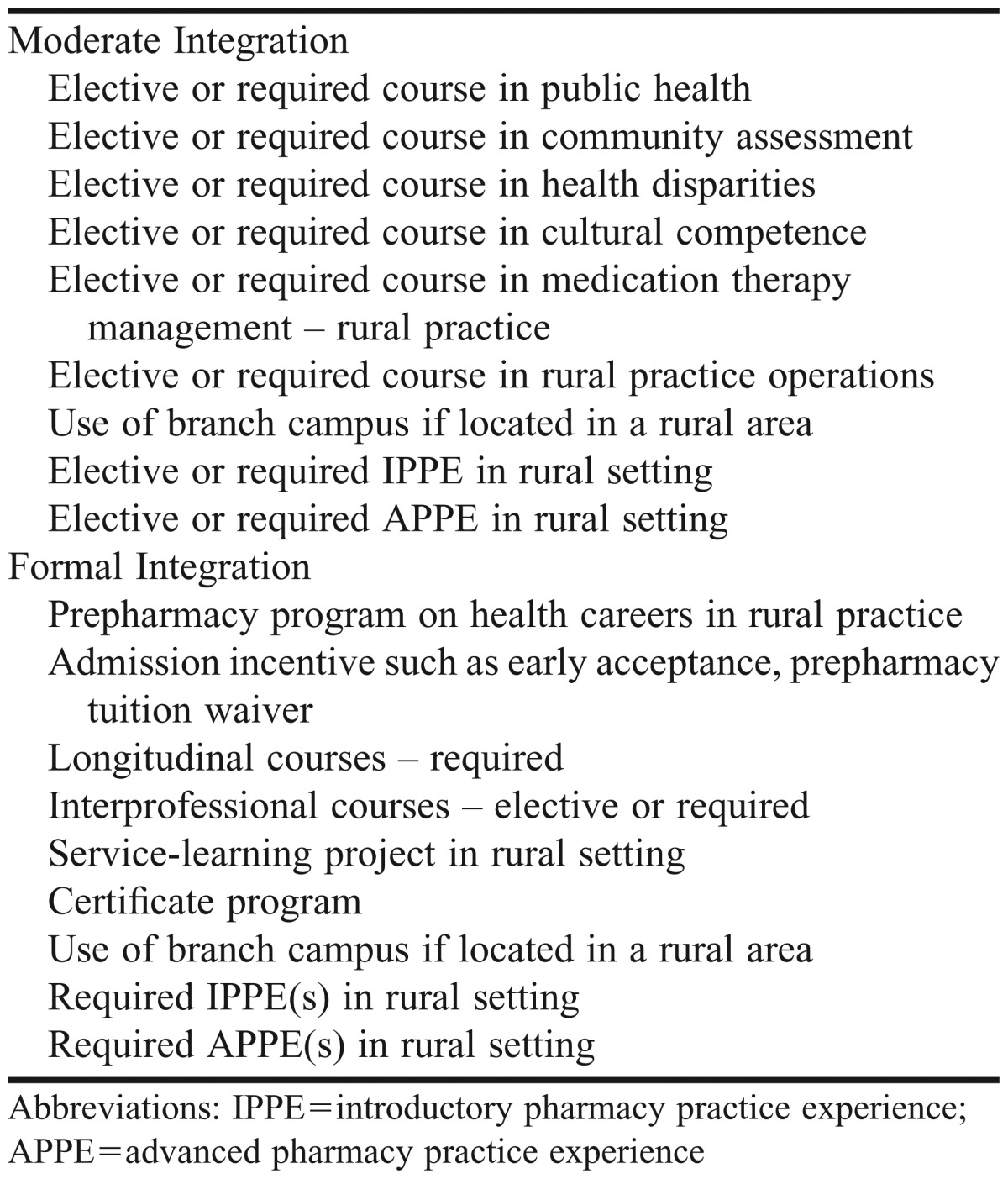

Review of the Web sites unveiled a wide range of offerings for classroom and/or experiential courses in rural health (Table 2). After recording the curricular offerings provided at ACPE-accredited colleges and schools, the authors divided the programs that offer rural health training to student pharmacists into 2 categories: moderate integration, which describes programs promoting some degree of curricular offerings in rural health; and formal integration, which describes programs that have developed official curricular programs in rural health education and training for student pharmacists. For ease of presentation and to make the information more useful to colleges and schools interested in expanding their rural health curricula, the information is presented in these categories and subdivided geographically.

Table 2.

Examples of Rural Health Coursework in Pharmacy Colleges and Schools in the United States

Moderate Integration

Examination of information from pharmacy colleges and schools designated as having moderate integration of rural health revealed that the level of integration varies greatly and includes classroom and experiential coursework, elective and required practice experiences, and optional participation in student-run clinics.

In Alabama, where the medical school at the University of Alabama offers the Rural Medical Scholars Program, Auburn University Harrison School of Pharmacy (HSOP) has increased its offerings in rural health. In 2007, HSOP, in collaboration with the University of South Alabama, opened a campus in Mobile for the purpose of decreasing the shortage of pharmacists across the state, particularly in the Gulf Coast area.16 As of August 2010, HSOP listed 11 sites for rural APPEs. A student may elect to complete up to 2 practice experiences at rural sites.17 In its development stage, a project entitled “Rural Health Initiative” featured a plan to use pharmacy and nursing students to provide health screenings in rural and underserved areas of Alabama. This initiative began in 2010 as a research proposal by students in the University’s Department of Industrial and Graphic Design to deliver health care to rural communities by developing a mobile screening clinic.18

The Harding College of Pharmacy, located on the campus of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS), opened a branch campus in the northwestern area of the state in an effort to resolve the shortage of healthcare professionals in the area.19 The University of Arkansas Medical Sciences Rural Programs is a collaboration of the University’s Center for Rural Health and the state’s 8 Area Health Education Centers (AHECs). The mission of these programs is to train healthcare professionals to provide care for rural Arkansans. In addition to training and recruiting family physicians for rural practice, these programs report successful integration of pharmacy and nursing students during rural practice experiences.20

Comprised of the Colleges of Dentistry, Health Care Sciences, Medical Sciences, Nursing, Optometry, Osteopathic Medicine, and Pharmacy, the Health Professions Division of Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, has developed an interprofessional approach to the education of all its students. Its mission is to train primary healthcare practitioners in a multidisciplinary setting, with an emphasis on medically underserved areas. In both classroom and experiential arenas, the division aims to alleviate Florida’s shortage of healthcare professionals by exposing the entire student body to the challenges, needs, and rewards of working with rural and underserved urban populations. The division’s Web site reports that all students are required to attend an ambulatory care practice experience in a rural or urban site, or both. Although 3 months of ambulatory care experience in a rural site serve as core practice experiences in the College of Osteopathic Medicine, similar requirements for core practice experiences were not found within the online curriculum of the College of Pharmacy.21

The University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy has implemented a policy that all students in the class of 2012, with the exception of those assigned to the regional Louisville and Owensboro Clinical Education Centers, are required to complete a minimum of 1 practice experience at a rural experiential site.22 The University of Maryland School of Pharmacy collaborates with the AHECs in the Eastern and Western regions of the state to provide clinical education and training in rural health for students in healthcare disciplines including pharmacy. Information from the Clinical Education Program within the Western Maryland AHEC states that 40% of its healthcare professions graduates have chosen careers in rural areas.23 In nearby Pennsylvania, the mission statement of Nesbitt School of Pharmacy and Nursing at Wilkes University highlights their graduates’ ability to practice in rural settings.24 Additionally, 1 of the core APPE experiences must occur in a rural setting.25

The University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy has been recognized for its community-based MTM services in several impoverished counties, an outreach in which both faculty members and students have been involved.26 A program entitled “Delta Pharmacy Patient Care Management Services” draws upon the experience of rural pharmacists to provide medication management to Medicaid beneficiaries. Although available online information does not explicitly list these sites as options for experiential training, assigning student pharmacists to these affiliated sites would likely provide a valuable learning opportunity.27

In contrast to many colleges and schools that emphasize APPEs in a rural setting, Presbyterian College School of Pharmacy, located in Clinton, South Carolina – a community of less than 10,000 – uses nearby pharmacy sites to provide the longitudinal IPPEs for their students. For example, during their first year, students complete their IPPE at sites within a 30-mile radius of Clinton.28 Also unique to this school is the Center for Entrepreneurial Development, which serves as a resource for start-up independent pharmacies. Because of its rural location, this center may also be a resource for students to learn about business in rural areas.29

East Tennessee State University Bill Gatton College of Pharmacy elaborates on its mission statement that the intent of the college’s work is to improve the health care of “the rural Appalachian community.” Although the Web site does not provide information specific to IPPEs or APPEs completed at rural sites, a required first-year course includes the exploration of the social aspects of health and illness in rural Appalachian regions. Approved electives offer insight into the care of patients who have chronic disease states and live in the region, herbal medicines popular with residents of the region, and health disparities within the Appalachian region.30

As a result of a state legislative mandate, West Virginia University (WVU) School of Pharmacy has made significant strides in establishing and formalizing experiential opportunities in rural health. Fourth-year students must complete at least two 5-week practice experiences at rural sites in West Virginia. Learning objectives specific to the rural health practice experience have been developed.31

In an effort to reach its goal of meeting the healthcare needs of Southern and Central Illinois, the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Pharmacy demonstrates some accomplishments in training students in a rural environment. For instance, 3 student pharmacist posters presented during the 2010-2011 academic year featured the use of telepharmacy to enhance rural patient care.32 In the nearby state of Indiana, Butler University College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences has directed monies from a $25 million grant to increase opportunities for student pharmacists to complete practice experiences in medically underserved and rural areas of the state. To obtain the grant, the college used the federal designation for medically underserved counties and developed a research study. Housing for students on practice experiences in the rural areas has been funded by this grant as well. This initiative has allowed for the matching of student pharmacists with midlevel practitioners in county health departments, even in areas with no active pharmacists.33 Additionally, a practice experience entitled Rural and Indigent Care is available to all students. Unique to the college’s Web site is a link to community resources, specifically low-cost health centers and clinics within each of the state’s counties.34

Drake University College of Pharmacy in Iowa collaborates with the Iowa Rural Health Association to bring together rural pharmacy practitioners and student pharmacists who seek experience in a rural setting. The student pharmacists participate in this collaboration as early as the second year of the curriculum. Although a review of the Web site yielded few specifics on curricular offerings in rural health, articles in a newsletter published by the Office of Experiential Education in the summer of 2011 offered students’ insights into the rewards and challenges experienced during a rural hospital APPE. The college also provides an IPPE with the Proteus Migrant Health Program. In this program, which is based in eastern Iowa, third-year students provide farm workers, immigrants, and laborers with much-needed health education, medications, screenings for chronic diseases, and administration of immunizations.35

The year 2011 marked the graduation of the inaugural doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) class at the Northeast Ohio Medical (NEOMED) University College of Pharmacy. In addition to providing an interprofessional approach to student learning throughout the 4-year curriculum, this college requires all student pharmacists (alongside medical students) to complete 1 APPE at a site that provides health care to an underserved population, some of which may be located in rural areas. The college is located in Rootstown, Ohio, which has a population of less than 10,000, and partners with regional hospitals and community clinics across northeast Ohio to provide experiential training. 36

In collaboration with the Office of Rural Health of Wisconsin, Rural Health Careers Wisconsin is an organization that partners with the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy to match students with IPPEs and APPEs in rural Wisconsin.37 To ensure equitable distribution of APPE students, the state is divided into 6 experiential education regions.38

Another program with a rural health focus is at the University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy. The University of Minnesota School of Medicine provides a successful exemplary program, the Rural Physician Associate Program, which produces a majority of graduates who enter their careers in rural settings of Minnesota. Building upon this success and partnering with the Minnesota AHEC program, the Department of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, located at the branch campus in Duluth, has created coursework that focuses on the healthcare needs of rural Minnesotans. One area of focus is interprofessional activities. This focus begins in the second year when student pharmacists are matched with students in medicine, nursing, and social work, all of whom work together to review patient cases and develop effective team-based communication techniques.39 Later, in the fourth year, students are assigned to geographically divided sections of the state for the completion of their APPEs.40

Although the Web site for the University of Colorado’s Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences does not discuss specific curricular offerings in rural health, it does describe a student academic community focused around rural health. It also describes 16 experiential sites in Diabetes and Anticoagulation that are offered in rural areas, but does not state whether these practice experiences are required or elective.41,42

Improving Health Among Rural Montanans (IPHARM) is a program involving students and faculty members in the Department of Pharmacy Practice at the University of Montana College of Health Professions and Biomedical Sciences Skaggs School of Pharmacy. In addition to the availability of an MTM/IPHARM-focused APPE, student pharmacists in their fourth year provide health counseling and screenings, such as bone density, hemoglobin A1c, cholesterol, and blood pressure, in an effort to increase access to health care in rural and underserved areas across the state.43 According to the Director of Experiential Education, students have become the “backbone” of the IPHARM program. (Gayle Hudgins, PharmD, e-mail, January 5, 2012). The 2010-2015 strategic plan of the College’s Department of Pharmacy Practice also includes 6 objectives designed to enhance the provision of rural health care by pharmacists and student pharmacists.44

In collaboration with the North Dakota Board of Pharmacy and the North Dakota Pharmacists Association, the North Dakota State University (NDSU) College of Pharmacy, Nursing, and Allied Sciences is best known for its Telepharmacy Project. A federal grant in 2002 drove the implementation of this project to use state-of-the-art technology to retain and/or restore pharmacy services in rural and underserved areas across the state. Both hospital and retail pharmacies in 36 counties (34 in North Dakota and 2 in Minnesota) participate in the project. Although the Web site for NDSU does not directly address student pharmacist involvement in this project,45 Naughton and colleagues at NDSU describe the creation of a pharmacy-led curriculum for a master’s degree in public health designed to train and advance student pharmacists in the role of rural and public health in a predominantly rural state.14

Fourth-year student pharmacists attending Oregon State University College of Pharmacy in Corvallis, Oregon, must complete 7 APPEs in their final year. According to a newsletter produced by the school in 2008, 1 of the 7 must take place in a rural setting.46

Formal Integration

The programs described in the above section primarily have singular or limited curricular offerings in rural health throughout their PharmD programs. In contrast, the programs described in the following section have a programmatic and longitudinal structure. As there are few programs with formal rural health pharmacy education curricula, this section is not divided geographically.

One of the older programs in rural pharmacy was created at the University of Arizona College of Pharmacy. As with other similar programs, the state legislature created the Rural Health Professions Program (RHPP) in 1996 to address the state’s shortage of healthcare providers, specifically in its rural areas. As the college gained experience and practitioners within the program, a certificate program evolved. Graduates who successfully participate in the RHPP receive a Certificate in Pharmacy-Related Health Disparities. Classroom offerings include a course on assessment of communities and 1 course exploring health disparities in pharmacy. A student in the RHPP must complete both IPPEs and at least 1 APPE in a rural setting. Initially, the RHPP class size was 4 students. As an indirect measure of its success, the number has increased to 12 to 14 per class year (Elizabeth Hall-Lipsy, PharmD, e-mail communication, January 3, 2012). In an effort to increase the number of potential RHPP preceptors, the form created by the college to be completed by any pharmacist interested in becoming a preceptor has a section in which the applicant states whether the site is located in a rural area of the state.47 Lastly, within the College of Pharmacy curriculum, opportunities in interprofessional education are offered not only to RHPP students but to all student pharmacists as well.48

The University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) College of Pharmacy has developed 2 unique programs in an effort to increase the number of graduates prepared for the provision of rural health care. The Rural Pharmacy Practice Educational Initiative seeks to assist students in applying to the college; targeted students are from either rural areas of Nebraska or from colleges located in rural areas. These applicants must express their commitment to return to rural Nebraska to practice pharmacy. Successful applicants are given early notice of their acceptance to the college. 49 The second program at UNMC, the Rural Health Opportunities Program (RHOP), is a partnership with Wayne State College (WSC), Chadron State College, and Peru State College. Successful applicants gain early acceptance to the College of Pharmacy, which is contingent upon meeting requirements of the prepharmacy curriculum at each school. There are 9 openings in each class at UNMC (3 for Wayne State College, 3 for Chadron State College, and 3 for Peru State College). Successful participation in the RHOP program at these 3 schools and progression through the UNMC curriculum leads to a tuition waiver of the 3 prepharmacy years, a significant incentive.50 Emphasis on training in rural health increases in the fourth year for RHOP students. While all student pharmacists in the UNMC College of Pharmacy curriculum are required to complete 1 APPE at a rural site, RHOP students are required to complete a minimum of 4 APPEs in a rural setting.49 Lastly, students admitted to the UNMC College of Pharmacy by way of the Rural Pharmacy Practice Educational Initiative or the RHOP are offered membership in the College’s Rural Pharmacy Student Association, an organization that serves to identify students who may wish to practice in rural areas as well as to foster their education and training.51

The University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy has created the Rural Pharmacy Program (RPHARM), which will be offered solely at the school’s branch campus in Rockford. The program saw its beginnings with the successful program in rural health at the University’s College of Medicine (RMED). These 2 programs will share not only interprofessional curricular content but also facilities on the Rockford campus. Core pharmacy coursework will be identical to that at the Chicago campus during its first 3 years. Courses in the RPHARM curriculum, which are supplemental to the core curriculum, will be provided in seminars, field trips, and other assignments. In their final year, RPHARM students will spend a minimum of three 6-week practice experiences in the same rural community and will work with an RMED student to complete a Community-Oriented Primary Care Project. The RPHARM’s inaugural class in 2010 admitted 6 students.52-54

In 2010, the University of Hawaii-Hilo College of Pharmacy received a multimillion-dollar grant to use health information technology to improve the provision of health care not only to rural areas but to all areas of the state. The college has since established the Center for Rural Health Science, with the goal of becoming a leader in rural health in the state of Hawaii. Details of the programs to be offered were unavailable at the time of this writing.55

DISCUSSION

A review of the Web sites provided by the colleges and schools of pharmacy in the US revealed a wide spectrum of course offerings with a focus on rural health. However, many Web sites provided no documentation of any classroom or experiential courses to educate and train its students for a career in rural pharmacy. Several colleges and schools provided a singular or limited coursework, often in the form of a single required or elective APPE. A few programs, some longstanding and some in the first stage of curricular design, have implemented innovative admission and curricular models. Table 2 lists examples of courses or experiences that have been implemented in a number of colleges and schools of pharmacy.

Although extensive, the review undertaken for this paper had limitations, the primary one of which is the use of institutional Web sites as the sole source of information. Although not ideal, searching individual college and school Web sites is a realistic way for colleges and schools interested in expanding their rural health offerings to begin gathering information. Although some colleges and schools may have curricular offerings related to rural health, if this information was not listed on their Web site, it is not included in this review. Institutions located in states that are primarily rural may presume that most if not all practice experiences take place in rural environments and thus do not promote them as such. Similarly, colleges and schools with newly opened branch campuses in nonurban locations may not advertise their practice sites as rural. Furthermore, if data related to rural health curricula were embedded in intranet sites or otherwise embedded external to the Web pages for curricula, faculty, student, or experiential education, it may have been missed. Finally, this review did not include details about rural health initiatives at colleges and schools whose Web sites referred to the programs but did not provide additional information. This aspect of the study design may have resulted in the inadvertent exclusion of colleges and schools with rural programs under development.

Despite these limitations, this review found that some programs could be emulated by other colleges and schools of pharmacy that wished to expand their rural health curricula. The more established programs have a defined structure with goals and outcomes, integration of the curriculum throughout all program years, and often some incentive in the form of tuition or a certificate. Furthermore, there is the potential for some well-established rural medical education programs, such as the Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho (WWAMI) Program, to partner with other colleges and schools of pharmacy. The WWAMI Program, a partnership between the University of Washington School of Medicine and the affiliated states, has been in existence for 40 years and has shown positive outcomes. 56

Simply locating students in a rural region does not adequately address the need represented in the PPACA. If we truly want student pharmacists to practice in rural areas after graduation, the majority of their experiences need to be in rural areas. As shown by academic colleagues in medicine, positive and extensive exposure to rural health care early in and throughout a curriculum can have a major impact on career decisions.57,58 Future areas of research might include a focus on outcomes for colleges and schools of pharmacy that have developed rural curricula. It is important to track the education and training, recruitment, and retention of graduates in rural areas and to share these findings with the Academy so that interested schools can better develop rural training programs.

SUMMARY

The number of colleges and schools providing some level of education and experience in rural health is likely insufficient to fulfill the pharmacy manpower needs of rural populations now and in the future. With the advent of federal and state-based initiatives to increase the primary care workforce and to enhance medication use and safety, particularly for the rural and underserved populations, more structured programs need to be created and implemented to best prepare our pharmacy practitioners for the future.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carrier ER, Yee T, Stark L. Matching supply to demand: addressing the US primary care workforce shortage. Policy Analysis No 7. National Institute for Health Care Reform. http://www.nihcr.org/PCP_Workforce.html. Accessed July 27, 2012.

- 2.American Colleges of Clinical Pharmacy. Health reform bill becomes law: includes key clinical pharmacy provisions. http://www.accp.com/announcements/healthreform.aspx. Accessed July 27, 2012.

- 3.What is Rural? Rural Information Center. United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library. http://www.nal.usda.gov/ric/ricpubs/what_is_rural.shtml#intro. Accessed October 7, 2012.

- 4. Recruitment and Retention of a Quality Health Care Workforce in Rural Areas. Number 3: Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. National Rural Health Association Issue Paper. May 2005. http://www.ruralhealthweb.org/go/left/policy-and-advocacy/policy-documents-and-statements/issue-papers-and-policy-briefs/. Accessed July 27, 2012.

- 5. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Service Administration Bureau of Health Professions. The pharmacist workforce: a study of the supply and demand for pharmacists. December 2000. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/pharmaciststudy.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2012.

- 6. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Service Administration Bureau of Health Professions. The adequacy of pharmacist supply: 2004-2030. December 2008. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/pharmsupply20042030.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2012.

- 7.Ricketts TC. Workforce issues in rural areas: a focus on policy equity. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(1):42–48. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orpin P, Gabriel M. Recruiting undergraduates to rural practice: what the students can tell us. Rural Remote Health. 2005;5(4):412–425. http://eprints.utas.edu.au/206/2/Recruiting_Rural_Students.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whelan JJ, Spencer JF, Rooney K. A “ripper” project: advancing rural interprofesional health education at the University of Tasmania. Rural Remote Health. 2008;8(3):1017–1025. http://eprints.utas.edu.au/7746/1/Jess_Whelan_1.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roche VF, Jones RM, Hinman CE, Seoldo N. A service-learning elective in native American culture, health and professional practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(6):Article 129. doi: 10.5688/aj7106129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown B, Heaton PC, Wall A. A service-learning elective to promote enhanced understanding of civic, cultural, and social issues and health disparities in pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(1):Article 09. doi: 10.5688/aj710109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seifert CF, Veronin MA, Kretschmer TD, et al. The training of a telepharmacist: addressing the needs of rural west texas. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3):Article 60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitley HP. A public health discussion series in an advanced pharmacy practice experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(6):Article 101. doi: 10.5688/aj7406101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naughton CA, Friesner D, Scott D, Miller D, Albano C. Designing a master of public health degree within a department of pharmacy practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):Article 186. doi: 10.5688/aj7410186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accredited Professional Programs of Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy. Chicago: Illinois; Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/shared_info/programsSecure.asp. Accessed July 27, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enhancing Health and Quality of Life. Harrison School of Pharmacy: Auburn University; July 2011 http://pharmacy.auburn.edu/policies_procedures_reports/pdf/hsop_2011.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Harrison School of Pharmacy: Auburn University; Rural and Out of Area. Office of Experiential Learning. http://pharmacy.auburn.edu/oel/pdf/appe_rural_outofarearotations.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Rural Health Initiative. Auburn University; Department of Industrial and Graphic Design. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Northwest Arkansas Campus. July 27, 2012 http://www.uamshealth.com/?id=5586&sid=1 . Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 20.UAMS Regional Programs. University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; July 27, 2012. http://www.uamshealth.com/?id=5031&sid=1 . Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 21.Health Professions Division. Nova Southeastern University; Fort Lauderdale-Davie, Florida: July 27, 2012. http://hpd.nova.edu/aboutus/mission.html. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 22.University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy Rural Rotation Site Requirement. July 27, 2012 http://pharmacy.mc.uky.edu/programs/EEP/RRS.php. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Western Maryland AHEC Clinical Education Program. Cumberland, Maryland. July 27, 2012 http://ahec.allconet.org/programs-clined.html. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkes University School of Pharmacy. July 27, 2012 http://www.wilkes.edu/pages/390.asp. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department of Pharmacy Practice. Wilkes University School of Pharmacy; Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: July 27, 2012. Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences Course Manual 2011-2012. http://www.wilkes.edu/Include/academics/pharmacy/Preceptor/APPE_Manual_2011_12.pdf. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lago B. UM School of Pharmacy Honored for Transformative Community Service; December 20, 2011. http://zing.olemiss.edu/um-school-of-pharmacy-honored-for-transformative-community-service. Accessed July 27, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delta Pharmacy Patient Care Management Project. University of Mississippi; July 27, 2012. http://pharmacy.olemiss.edu/pharmacy_practice/deltaproject.html. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 28. Experiential Education. Presbyterian College School of Pharmacy. Clinton, South Carolina. http://pharmacy.presby.edu/experiential-education. Accessed July 27, 2012.

- 29.Dyer S. PC announces Center for Entrepreneurial Development at School of Pharmacy; September 17, 2010. July 27, 2012. http://www.presby.edu/news/sep/1710-pharmacy. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gatton College of Pharmacy Catalog 2011-2012. East Tennessee University; Johnson City, Tennessee: July 27, 2012. http://www.etsupharmacy.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/Catalog-2011-12.pdf. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rural Health Rotation Learning Objectives. School of Pharmacy, West Virginia University; Morgantown, West Virginia: July 27, 2012. Office of Experiential Learning. http://pharmacy.hsc.wvu.edu/explearning/Advanced-Pharmacy-Practice-Experiences-Curriculum(/Rotation-Goals-and-Objectives/Rural-Health. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. School of Pharmacy; Edwardsville, Illinois: July 27, 2012. Capstone Project Poster Titles 2010-2011. http://www.siue.edu/pharmacy/pdf/ProjectPosterTitles2011.pdf. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pharmacy Students Work with Indiana’s Underserved, Campus News. Butler University; Indianapolis, Indiana: March 15, 2011. http://www.butler.edu/absolutenm/templates/?a=2601. Accessed July 27, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Low Cost Health Centers and Clinics. College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences – Community Health Resources. Butler University; July 27, 2012. http://www.butler.edu/community-health/centers. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Students Help Take Health Care to Those Who Need it Most. Drake University College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences; Des Moines, Iowa: July 27, 2012. Office of Experiential Education, Summer 2011. http://www.drake.edu/cphs/experiential/pharmacy/news/summer_2011_final.pdf. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 36.College of Pharmacy. Northeast Ohio Medical University; http://www.neomed.edu/academics/pharmacy. Accessed July 27, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pharmacy Clerkships (IPPE/APPE) Rural Health Careers Wisconsin. July 27, 2012 http://www.rhcw.org/PharmacyClerkship.aspx. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 38.APPE Site Presentation Schedules. University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy; July 27, 2012. 2011 Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE) Presentations, Greater Wisconsin. http://pharmacy.wisc.edu/career-development-services/career-fair/information-students/appe-clerkship-presentations. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 39.Interprofessional Standardized Patient Experiences, College of Pharmacy - Duluth. University of Minnesota; July 27, 2012. http://www.pharmacy.umn.edu/duluth/aboutcollege/interprofessional/ISPEs/home.html. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 40.Experiential Education Program. University of Minnesota; July 27, 2012. http://www.pharmacy.umn.edu/pharmd/eep/home.html. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 41.Advanced Student Academic Communities. Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences; July 27, 2012. http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/pharmacy/Resources/OnCampusPharmDStudents/StudentOrganizationsNew/Pages/StudentAcademicCommunities.aspx. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Community Programs and Outreach. Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences; July 27, 2012. http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/pharmacy/AboutUs/OurCommunity/CommunityPartners/Pages/CommunityProgramsOutreach.aspx. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 43.The IPARM Project. Department of Pharmacy Practice, Skaggs School of Pharmacy, The College of Health Professions and Biomedical Sciences. July 27, 2012 University of Montana. http://www.health.umt.edu/schools/practice/ipharm/. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivey M. College of Health Professions and Biomedical Sciences. University of Montana; July 27, 2012. Area: Rural Health Care, Strategic Plan 2010-2015, Department of Pharmacy Practice. August 2010. http://www.health.umt.edu/schools/practice/DeptStrategicPlan.htm. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 45. Telepharmacy. North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota. http://www.ndsu.edu/telepharmacy/. Accessed July 27, 2012.

- 46.“Passing on the Wisdom: Southern Oregon preceptors.”. News for the Alumni and Friends of the College of Pharmacy, Fall 2008, p. 3, College of Pharmacy, Oregon State University. July 27, 2012 http://pharmacy.oregonstate.edu/sites/default/files/Fall_08.pdf. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preceptor Interest Form. University of Arizona; July 27, 2012. http://www.pharmacy.arizona.edu/programs/rotations/preceptor-interest-form. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rural Health Professions Program. College of Pharmacy. University of Arizona; Tucson, Arizona: July 27, 2012. http://www.pharmacy.arizona.edu/programs/rotations/rural-health. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 49.Early Acceptance. University of Nebraska Medical Center; Omaha, Nebraska: July 27, 2012. Doctor of Pharmacy Program, Admissions, College of Pharmacy. http://www.unmc.edu/pharmacy/pharmd_early_acceptance.htm. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rural Health Opportunities Program, College of Public Health Rural Health Education Network. University of Nebraska Medical Center; Omaha, Nebraska: July 27, 2012. http://www.unmc.edu/rhen/RHOP_Programs.htm. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rural Pharmacy Student Association. University of Nebraska Medical Center; Omaha, Nebraska: July 27, 2012. Student Life, College of Pharmacy. http://www.unmc.edu/pharmacy/pharmd_studentlife.htm. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 52.The Doctor of Pharmacy Program at our Rockford Campus. University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy; July 27, 2012. http://www.uic.edu/pharmacy/rockford/index.php. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doctor Pharmacy Experiential Education Curriculum. University of Illinois College of Pharmacy at Rockford; July 27, 2012. http://www.uic.edu/pharmacy/rockford/Experiential_Education_Curriculum-Rockford.pdf. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 54.July 27, 2012 “Our Farm” and “Life, Rockford-Style”, The Rockford Files, UIC Pharmacist. Summer 2011. http://issuu.com/uicpharmacy/docs/uicpharmacistsummer2011. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 55. UH Hilo Launches New Rural Health Center, UH Hilo Press Release, News and Events, October 17, 2010, University of Hawaii – Hilo. http://hilo.hawaii.edu/news/press/release/989. Accessed July 27, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.WWAMI program. University of Washington Medicine; May 23, 2012. http://uwmedicine.washington.edu/Education/WWAMI/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed . [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quinn KJ, Kane KY, Stevermer JJ, et al. Influencing residency choice and practice location through a longitudinal rural pipeline program. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1397–1406. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318230653f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henry JA, Edwards BJ, Crott B. Why do medical graduates choose rural careers? Rural Remote Health. 2009;9(1)(1083) http://www.rrh.org.au/articles/subviewaust.asp?ArticleID=1083. Accessed October 4, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]