Abstract

Noroviruses are an important cause of epidemic acute gastroenteritis and the viruses recognize human histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs) as receptors. The protruding (P) domain of noroviral capsid, the receptor binding domain, forms subviral particles in vitro that retain the receptor binding function. In this study we characterized the structure and HBGA-binding function of the P particle. Structure reconstruction using cryo-EM showed that the P particles are comprised of 12 P dimers that are organized in octahedral symmetry. The dimeric packing of the proteins in the P particles is similar to that in the norovirus capsid, in which the P2 subdomain with the receptor-binding interface is located at the outermost surface of the P particle. The P particles are immunogenic and reveal similar antigenic and HBGA-binding profiles with their parental virus-like particle, further confirming the shared surface structures between the two types of particles. The P particles are easily produced in E. coli and yeast and are stable, which are potentially useful for broad application including vaccine development against noroviruses.

Introduction

Noroviruses, formally called Norwalk-like viruses, are a group of single-stranded, positive sense RNA viruses within the family Caliciviridae (Green, Chanock, and Kapikian, 2001). The viruses cause epidemic acute gastroenteritis affecting people in both developing and developed countries (Green, Chanock, and Kapikian, 2001; Tan, Farkas, and Jiang, 2008; Tan and Jiang, 2007). Noroviruses contain a protein capsids that is composed of a single major structural viral protein, the capsid protein (VP1). X-ray crystallographic analysis of the recombinant capsid of Norwalk virus revealed a T=3 icosahedral symmetry with 180 molecules of the capsid protein organized into 90 dimeric capsomers (Prasad et al., 1999). The capsid protein consists of two domains, the shell (S) and the protruding (P) domains, linked by a short hinge. The S domain is involved in the icosahedral shell formation, whereas the P domain forms the arch-like structure, protruding from the shell. The P domain can be further divided into P1 and P2 subdomains, each corresponding to the leg and the head of the arch-like P dimer (Prasad et al., 1999). P1 subdomain consists of largely anti-parallel β-strands and a α-helix, whereas P2 is an insertion into P1 and forms an anti-parallel six-stranded β-barrel. As the P2 subdomain is located at the outmost surface of the viral capsid and is evolutionarily highly variable, it is believe that P2 subdomain is essential for host interactions. Indeed, the recent X-ray crystallographic study followed by mutagenesis investigations showed that the HBGA-binding interface is located in the P2 subdomain of the P dimer (Bu et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2003; Tan et al., 2008b).

The crystal structure of noroviral capsid indicates that the P domain is mainly responsible for dimeric interactions that stabilize the viral capsid. Extensive intermolecular interactions between the two P domain monomers have been described (Cao et al., 2007; Prasad et al., 1999). Expression of the P domain alone in vitro has resulted in dimerization (P dimer) and the formation of a large complex, the P particles (Tan, Hegde, and Jiang, 2004; Tan and Jiang, 2005a; Tan and Jiang, 2005b; Tan and Jiang, 2007; Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006). Gel filtration of the P particle showed a molecular weight of ~830 kDa, suggesting that it is composed of 24 P monomers, most likely organized into 12 P dimers (Tan and Jiang, 2005b). Linking of a cysteine-containing short peptide to either end of the P domain enhanced and stabilized the P particle formation. Saliva-based HBGA-binding assay showed that both the P dimer and the P particle retain binding capability to human HBGAs and the binding affinity of the P particle is much stronger comparing to the P dimer, similar to that of virus-like particles (VLP) (Tan and Jiang, 2005b).

Noroviruses recognize human HBGA-receptors in a strain-specific manner [Reviewed in (Tan and Jiang, 2005a; Tan and Jiang, 2007)]. Eight distinct HBGA-binding patterns of noroviruses have been described (Huang et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2005). Human HBGAs are complex carbohydrates that consist of an oligosaccharide linking to proteins or lipids on mucosal epithelia of the respiratory, genitourinary, and digestive tracts, or as free oligosaccharide in biological fluids such as saliva and milk (Marionneau et al., 2001; Ravn and Dabelsteen, 2000). All three major HBGA families, the ABO, Lewis, and secretor families, have been shown to be involved in norovirus recognition (Huang et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2005; Tan, Farkas, and Jiang, 2008; Tan and Jiang, 2005a; Tan and Jiang, 2007). An association between the host HBGAs and the clinic infection and illness of a few strains has been shown by a number of volunteer studies (Hutson et al., 2005; Hutson et al., 2002; Lindesmith et al., 2003) and outbreak investigations (Tan et al., 2008a; Thorven et al., 2005). However, direct evidence of such a link for many other strains remains lacking.

Noroviruses are difficult to study owing to the lack of effective cell culture and animal models. Research on the norovirus-host interaction is relied on the use of VLPs that can only be generated through a eukaryotic system, which is time consuming and expensive. In this study we performed structural analysis of the P particles of VA387 that represents the most circulated GII-4 genotype and one of the eight described HBGA-binding patterns (binding to A, B, and H antigens). In addition, we studied the HBGA-binding activity, immunogenicity, and application of the P particles in outbreak investigations in comparison with VLPs. Our results demonstrated that the easily produced P particle could be a substitute of VLP in characterization of virus-host interaction and immune responses and as a candidate vaccine for noroviruses.

Materials and methods

Expression of P particles in E. coli

The P particle expression constructs of VA387 with (HP-CDCRGDCFC) or without (P-CDCRGDCFC) the hinge and of Norwalk virus with the hinge (CNGRC-HP), respectively, were made by cloning the cDNA sequence encoding the P domain with or without the hinge into the vector pGEX-4T-1 (GST-gene fusion system; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) at the BamHI/NotI sites as described previously (Tan, Hegde, and Jiang, 2004; Tan and Jiang, 2005b; Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006). To enhance the P particle formation a cysteine-containing short peptide were linked to the N- (CNGRC-HP) or C- (HP-CDCRGDCFC and P-CDCRGDCFC) termini of the P domains. The constructs were expressed in E. coli strain BL21 as described previously (Tan, Hegde, and Jiang, 2004; Tan and Jiang, 2005b; Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006). Briefly, expression was conducted at room temperature (~25 °C) overnight following an induction with 0.25 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Purification of the recombinant GST-P domain fusion protein was performed using Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (Amersham Bioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The P proteins were released from GST by thrombin (Amersham Bioscience) cleavage at room temperature for 16 hours. Further purification was conducted by gel filtration chromatography powered by an AKTA FPLC System (Amersham Bioscience) as described previously (Tan, Hegde, and Jiang, 2004; Tan and Jiang, 2005b; Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006).

Expression of P particles in yeast

The P particle without the hinge (P-CDCRGDCFC) of VA387 was also expressed in yeast. The expression construct was made by PCR-amplification of the coding sequences of GST, P domain, and the peptide of CDCRGDCFC from the P-CDCRGDCFC construct above (Tan and Jiang, 2005b) and cloning the PCR product into the plasmid pPICZ-A (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at the EcoR I/Not I sites. The construct was then expressed in yeast Pichia strains X-33 according to the protocol provided by the EasySelect Pichia Expression Kit (Invitrogen). The P protein was purified using Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow as described above.

Electron cryomicroscopy imaging

Aliquots (3–4 µl) of the purified P particle solution were flash frozen using a home-made plunge freeze apparatus onto Quantifoil grids with 2µm holes in liquid ethane cooled by liquid N2. The sample grids were loaded into the microscope using a Gatan side-entry cryoholder. Low dose images (~20e/A2) were recorded on Kodak SO163 films using CM200 cryo-microscope with a field emission gun operating at 200 KV. The images were taken at nominal magnification of 50,000 and in the defocus range of 2.0 to 4.0 µm. Particle aggregation of varying extents was observed. The micrographs with less severe aggregation were selected and digitized using a Nikon Super CoolScan 9000ED scanner at step size of 6.35 µm /pixel. The scanned images were binned resulting in the final sampling of the images at 2.49Å/pixel for further image processing and 3-D reconstruction.

Electron cryomicroscopy image processing and 3-D reconstruction

The images of the P Particles were selected semi-automatically using EMAN’s boxer program (Ludtke, Baldwin, and Chiu, 1999). The selected images were manually filtered to exclude false positive, which was done at the 60Å low-passed version of the original micrograph to enhance clarity. The EMAN’s ctfit program (Ludtke, Baldwin, and Chiu, 1999) was used to manually determine the contrast-transfer-function (CTF) parameters associated with the set of particle images originating from the same micrograph. 29260 and 23920 images were chosen from the P particles with (HP-CDCRGDCFC) and without (P-CDCRGDCFC) the hinge, respectively. The images were then CTF phase-corrected prior to further processing. Initial model of the P particles were created using EMAN’s startoct program (Ludtke, Baldwin, and Chiu, 1999). Then the EMAN’s refine program (Ludtke, Baldwin, and Chiu, 1999; Ludtke et al., 2001) was used to iteratively determine the center and orientation of the raw particles and reconstruct the 3-D maps from the 2-D images by the EMAN make3d program until convergence. Octahedron symmetry was imposed during reconstruction for two types of P particles. The resolution of the reconstructions was measured by splitting the data set into two halves, even and odd, whose 3D maps were then generated and compared, indicating that the resolution resulted in 0.5 Fourier shell correlation (Heel, 1987).

Electron cryomicroscopic model evaluation and analysis

The crystal structures of noroviral P domains of VA387 (Cao et al., 2007) was fitted into the 3D structure of the P particle using Chimera software (Pettersen E. F, 2004). Simple rigid body motion was considered to find the best matching of the x-ray structure to the 3D structure of P-particles. No steric crash was seen when the fitted dimer was duplicated symmetrically to produce octahedral structure.

Saliva samples and their HBGA phenotyping

The 141 saliva samples were collected from two Chinese populations in the east (Jiangsu province) and the northwest (Shanxi province) parts of China originally for an investigation of two noroviral outbreaks (Tan et al., 2008a). The ABH and Lewis HBGAs in the saliva samples were determined by EIA assays using the corresponding monoclonal antibodies against individual HBGAs (A, B, H1, Lea, Leb, Lex, Ley) as described previously (Tan et al., 2008a). Briefly, boiled saliva samples were diluted and coated on 96-well microtiter plates (Dynex Immulon; Dynatech, Franklin, MA). The corresponding monoclonal antibodies against individual antigens were added. After incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugates, the signal intensity were displayed by adding HRP substrate reagents (TMB kit, Kierkegaard & Perry Laboratory, Gaithersburg, MD) (Tan et al., 2008a).

HBGA binding and blocking assay

The saliva- and synthetic oligosaccharide-based binding assays were performed basically as described elsewhere (Huang et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2005). Briefly, boiled saliva samples were diluted 1000× and coated on 96-well microtiter plates (Dynex Immulon; Dynatech, Franklin, MA). After blocking by nonfat milk, baculovirus-expressed, sucrose-gradient purified VLPs (0.5 µg/ml) of VA387 or Norwalk virus, or P particles (0.25 µg/ml) of these two strains, respectively, were added. The bound VLP/P particle were detected using a rabbit anti-VA387 or Norwalk virus VLP antiserum (1:3,300), followed by the addition of HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (ICN, Aurora/OH). The blocking effects of the antibodies induced by VLP and P particle on binding of VLP to HBGAs were determined by incubation of the VLPs with the corresponding serum at given dilutions for 10 min before adding them to the coated saliva. The synthetic oligosaccharide-based binding assay was performed using a panel of oligosaccharides representing 9 different HBGAs (A, B, H1, H2, H3, Lea, Leb, Lex, and Ley) as reported previously (Huang et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2005).

Immunization of mice

Purified P particle and VLP of VA387 were used to immunize mice intranasally without adjuvant to compare their immunogenicity. 45 µg recombinant VLPs or P particles (P-CDCRGDCFC) of VA387 were administered to each mouse (three mice/group) for three times at two week-intervals and sera were collected at week 6. The immunogenicities of the VLP and P particle were determined by Elisa to measure the immunoreactivities of sera to P particle as described previously (Tan et al., 2004). Briefly, the P particle at 0.5 ng/µl was coated on 96-well microtiter plates (Dynex Immulon; Dynatech, Franklin, MA) (100 µl/well) overnight at 4°C. After blocking by nonfat milk, the mouse sera at indicated dilutions were incubated with the coated P particle and the bound antibodies were shown by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody [HRP-goat-mouse antibody (ICN, Aurora/OH)]. The results were revealed as color intensities after incubation with HRP substrate (TMB kit, Kierkegaard & Perry Laboratory, Gaithersburg, MD).

Results

Production of P particles in E. coli and yeast

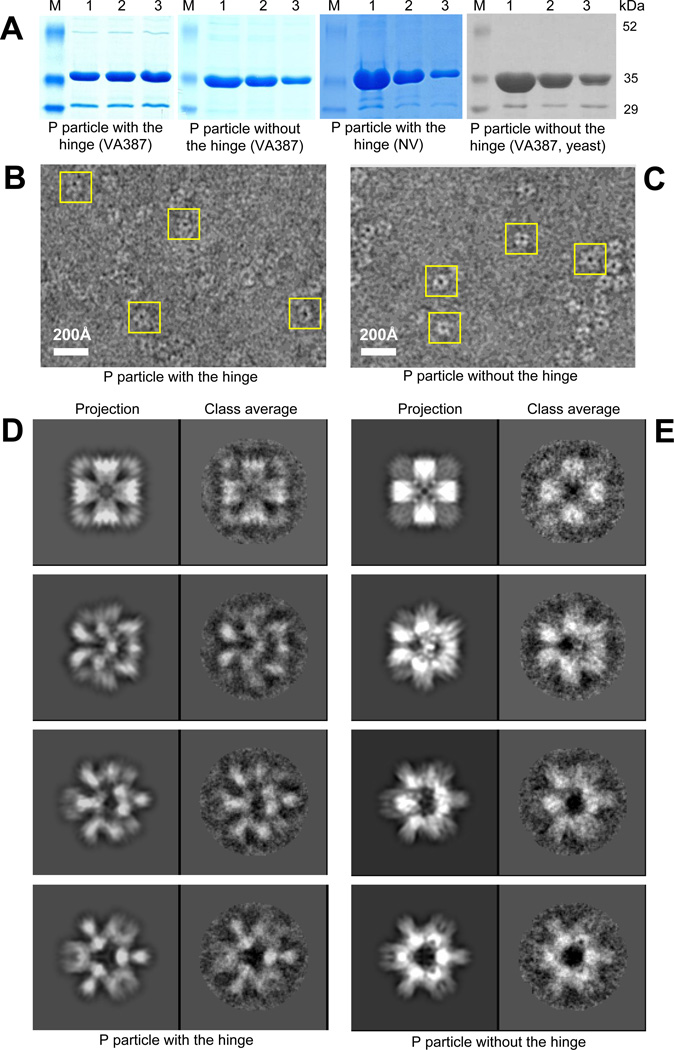

The P particles of VA387 (GII-4) and Norwalk virus (NV, GI-1) were produced in E. coli at a yield of ~5 mg/liter culture (Fig 1A). In addition, the VA387 P particle was also expressed in yeast Pichia, with a yield of ~7.5 mg/liter culture (Fig 1A, the fourth panel). All these P particles showed a single major protein band of ~35 kDa in SDS-PAGE gels (P protein monomer) as determined by Western blot analysis using antibody against norovirus VLPs (Tan, Hegde, and Jiang, 2004; Tan and Jiang, 2005b). They formed a major peak of ~850 kDa in gel filtration with Superdex 200 (Tan and Jiang, 2005b; Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006) and revealed homogenous ring-shaped images in the electron microscopy (Fig 1 B and C, data not shown). Highly purified P particles for cryo-electron microscopy (see below) were obtained by gel-filtration.

Figure 1.

P particle production and cryo-EM image processing. A, SDS-PAGE gels show recombinant P proteins (particles) of VA387 (1st, 2nd and 4th panels) and Norwalk virus (NV, 3rd panel) that were expressed in E. coli (the first three panels) and yeast (the last panel). The gels were stained by brilliant blue R250. Labelings below the gels are the construct names of the P particles. Lanes 1 to 3 were three eluates of the P particles from the affinity columns treated by thrombin. M=protein standard. B to E, micrographs of the P particles with (B) or without the hinge (C) of VA387 that were taken at 4.5 and 4.6 micron underfocus, respectively. The yellow rectangles indicate the typical P particle images for image processing and 3-D structure reconstruction. The 3-D model projections and the corresponding class averages of particle images are shown for multiple views ranging from four fold (top row) to three fold in D and E for these two types of P particles, respectively.

3D structure reconstruction of noroviral P particles

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) of P particles of VA387 with or without the hinge revealed a central hole in the particles (Fig 1B and C). The majority of the particles were rounded with six spikes protruding outward, while relative few exhibited four-fold symmetry. Orientation determination was done iteratively. The noise of the raw particle images was substantially suppressed when the 2D average was performed to obtain the class average (Fig 1D and E). In the reference projection, the noise is almost completely suppressed as a result from averaging in 3D during the reconstruction from the previous iteration. Some differences between the projections of the two P particles are noted, suggesting slightly different intra-subunit arrangement between the P particle with or without the hinge. The overall inter-subunit arrangement, however, appeared similar.

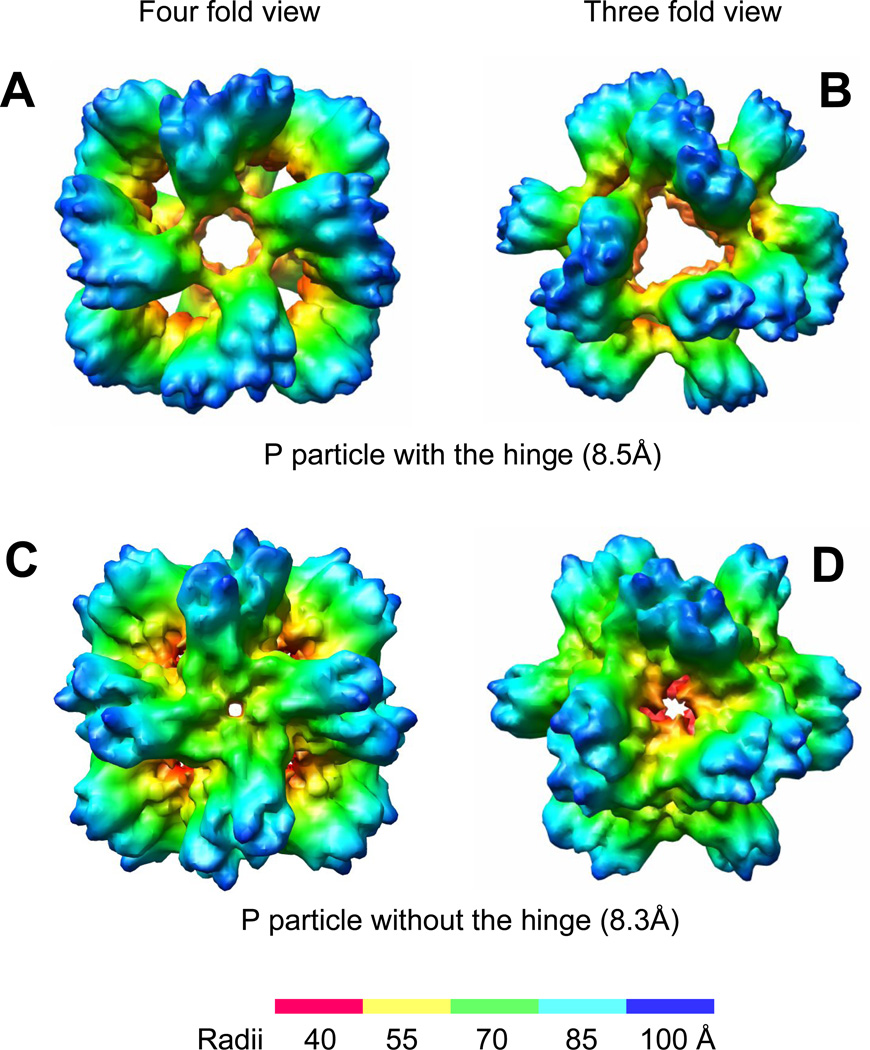

The final cryo-EM structures of the two VA387 P particles have been resolved at a resolution of ~8.4Å (Fig 2). Both P particles were packed in a spherical octahedral symmetry with a similar size of ~20 nm in diameter and a center cavity. Each P particle contains 12 P dimer subunits, consistent with the previous calculation based on the molecular weight estimated by gel filtration (Tan and Jiang, 2005b). Moving radially outward from the center cavity is the legs of arch-like P dimers which formed tetramer contact at the four-fold view (Fig 2 A and C). Protruding further outward from the legs is the top of arch-like P dimer. However, the two P particles also have some obvious differences. The P particle with the hinge, for example, shows much more loose inter-subunits packing at both the four- and three-fold contacts than those of the P particles without the hinge (Fig 2, compare A with C, B with D). As a result the center cavity of the P particle with the hinge is bigger than that of the P particle without the hinge.

Figure 2.

The final cryo-EM structure of the P particle of VA387. A and B, the P particle with the hinge (8.5Å) at the four-fold (A) and the three-fold views (B) shows a lower compactness with larger center cavity. C and D, P particle without the hinge (8.3Å) at the same views shows a higher compactness with smaller center cavity. The radii of the P particle are shown by different colors as indicated.

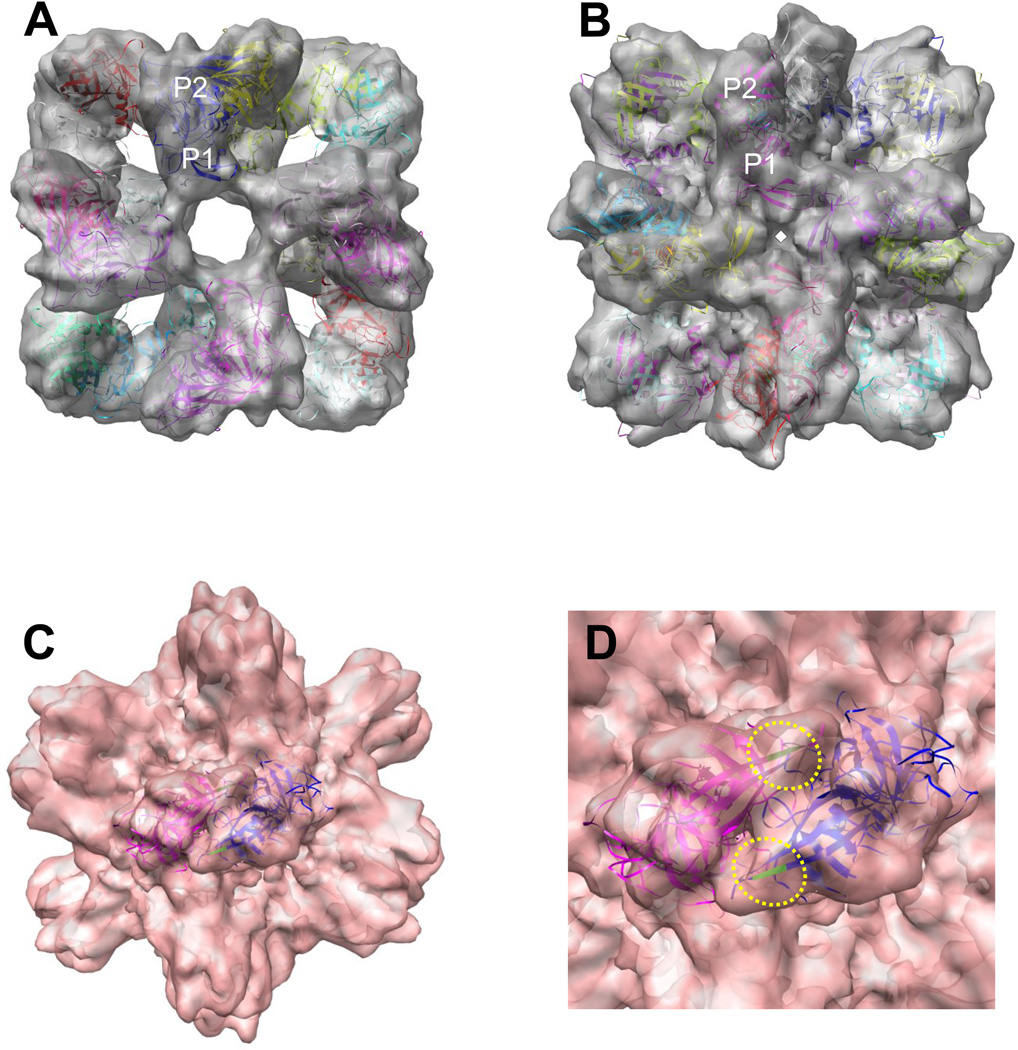

Exposure of the HBGA-binding interface on the P particles

Fitting of the P domain crystal structures of VA387 (Cao et al., 2007) into the 3D cryo-EM structures of the P particles elucidates additional detailed structural features (Fig 3 A and B). The orientation of the arch-like P dimer in the P particle is similar to that in the VLP, in which the P1 subdomain or the legs of the arch-like structure is inward to the center cavity, whereas the P2 subdomain or the head of the arch is outward to the surface of the P particle. Both the N- and C-termini of the P protein are located at the innermost core of the P particle, which plays an important role in the formation and stability of the P particles.

Figure 3.

Fitting of the crystal structures of the P dimers into the 3D structures of the P particles. A and B, fitting of the crystal structure of VA387 P dimer (colored ribbon model) into the cryo-EM density maps (transparent gray, four-fold view) of the P particles with (A) and without (B) the hinge, respectively, elucidates the structure and orientation of the P dimer within the P particles. The P1 subdomain is inward to the center cavity, while the P2 is outward to the surface of the P particle. C, fitting of the crystal structure of a VA387 P dimer (ribbon model, colored in red and blue, respectively) with indications of two residues T344 and R345 (green) into a P dimer (two fold top view) of the P particle without hinge. D, an enlargement of (C) to show the two HBGA-binding interfaces (yellow dashed circles) on the outmost surface of the P particles. Residues T344 and R345 (green) represent the center of the receptor binding interface.

Our previous data showed that an addition of cysteines at either terminus of the P domain stabilizes the P particle formation, most likely by forming inter-subunit disulfide bonds (Tan and Jiang, 2005b). In contrast, the hinge prevents the P particle formation, probably by increasing the energy cost to twist the legs of the P dimer (see below) or simply being a sterically unfavorable factor (see discussion). Structural differences of each P dimer between the P particle and VLP were also noted, in which the legs of the P dimer in the P particle twisted an angle to fit into the octahedral P particle (Fig 2 and 7), while no such twist occur in the icosahedral VLP. Most importantly, the HBGA-binding interface (Cao et al., 2007; Tan et al., 2008b) is located at the top of each arch-like subunit, corresponding to the outermost surface of the P particle, and similar to that on the VLP, the receptor-binding site is present at the interface between the two P monomers (Fig 3C and D).

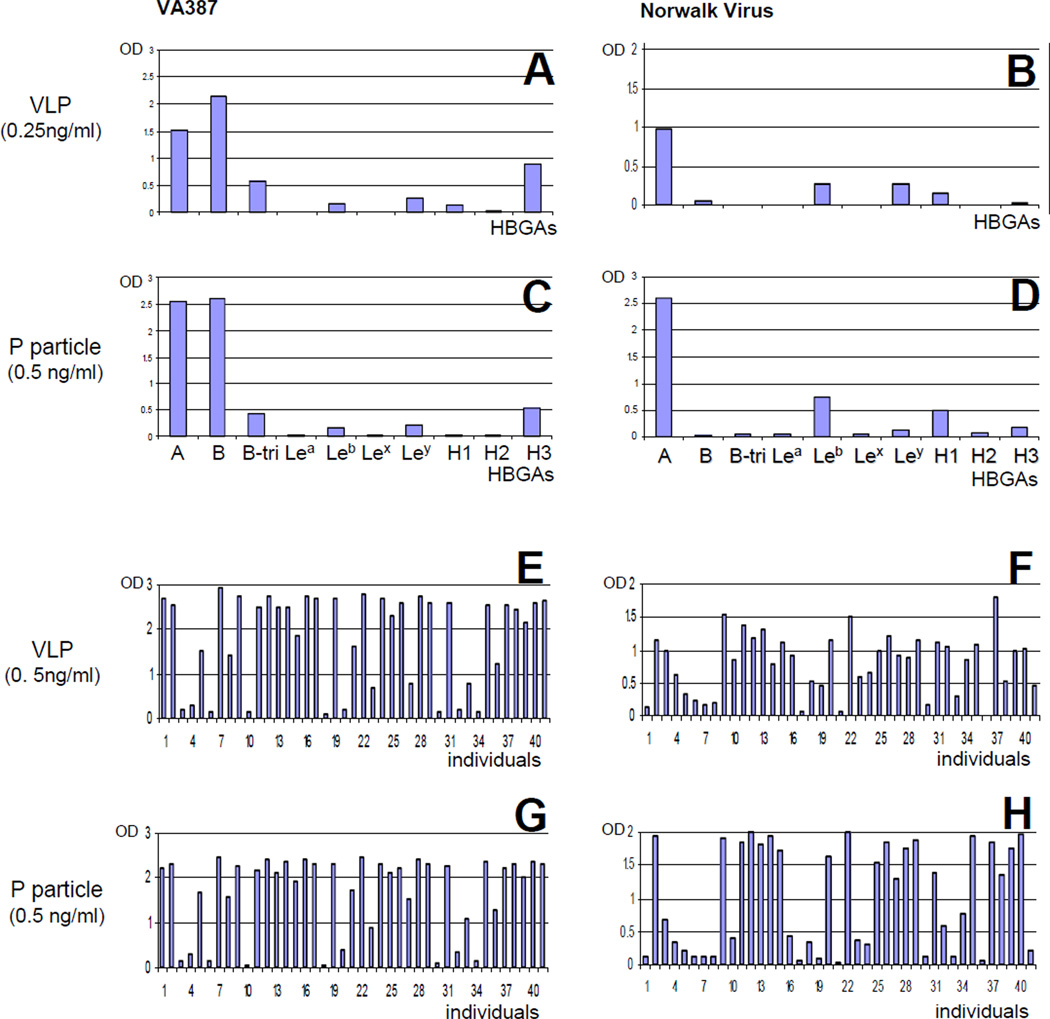

The P particle shares similar HBGA-binding profile as that of VLP

This is demonstrated by a comparison of the HBGA binding activities of P particles with VLPs to a panel of oligosaccharides representing 9 HBGAs (A, B, H1, H2, H3, Lea, Leb, Lex, Ley) and a panel of saliva samples (n = 41) from individuals with variable HBGA types (Fig 4). Both VLP and P particle of VA387 bound strongly to A and B, moderately to H3, and weakly to Leb and Ley antigens. However, it was noted that the relative binding affinity of P particle to H1 and H3 was weaker than that of VLP (Fig 4, compare A and C). Similarly, while both VLP and P particle of Norwalk virus showed a similar binding profile to the tested HBGAs, minor binding variations between the two types of particles were seen (Fig 4, compare B and D). Binding of both P particles and VLPs of the two strains to a panel of 41 saliva simples revealed similar results. In both cases the two types of particles showed a similar binding profile with minor variations (Fig 4, compare E and G, F and H, respectively).

Figure 4.

Noroviral P particle and VLP share similar HBGA-binding profiles to a panel of synthetic oligosaccharides representing different HBGAs and a penal of saliva samples. A to D, HBGA-binding profiles of VLPs (A and B) and P particles (C and D) of VA387 (A and C) and Norwalk virus (B and D) to a panel of synthetic oligosaccharides representing 9 HBGAs (X-axis). Y axis (optical density, OD) represents the binding affinities between the VLP/P particle and the oligosaccharides that were average of two experiments. All oligosaccharide are linked to PAA (polyacrylamide) except A- and B-antigen that is linked to bovine serum albumin (BSA). E to H, the saliva-binding affinities (Y-axis) of VLP (E and F) and P particle (G and H) of VA387 (E and G) and Norwalk virus (F and H) to a penal of 41 saliva samples (X-axis). The results were average of a triplicate experiments.

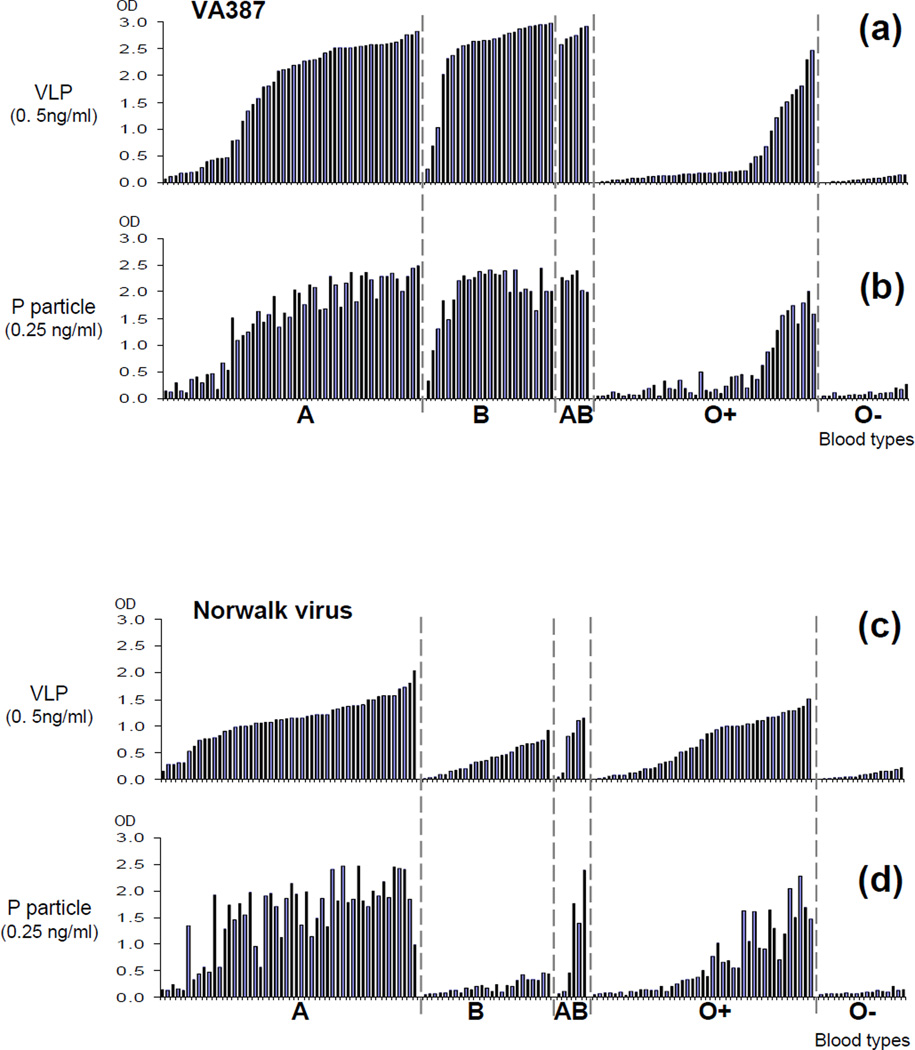

We also evaluated the usefulness of P particles in outbreak investigation of norovirus gastroenteritis by testing a large number of saliva samples from patients and asymptomatic controls in norovirus outbreaks for their ability to bind P particles and VLP. Among 146 saliva samples with known HBGA phenotypes collected from two outbreaks (Tan et al., 2008a), the P particles revealed very similar binding profiles to those of VLPs for both VA387 and Norwalk virus, although again minor binding variations were also seen [Fig 5, compare (a) and (b), (c) and (d), respectively]. These binding results were consistent with the blood types of individual saliva samples as anticipated according to our previous studies (Huang et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2005). Thus, the P particle may be useful for large population studies on norovirus-HBGA interaction.

Figure 5.

Noroviral P particle and VLP share similar binding profiles to 141 saliva samples collected from noroviral outbreaks. The binding results of VLPs are sorted ascendingly by OD values in each blood type, respectively, in (a) (VA387) and (c) (Norwalk virus), while the corresponding binding results of the P particles are shown in the same sample order in (b) (VA387) and (d) (Norwalk virus). ABO secretor blood types are indicated, while O- represents the saliva of nonsecretors. The results were average of a triplicate experiment.

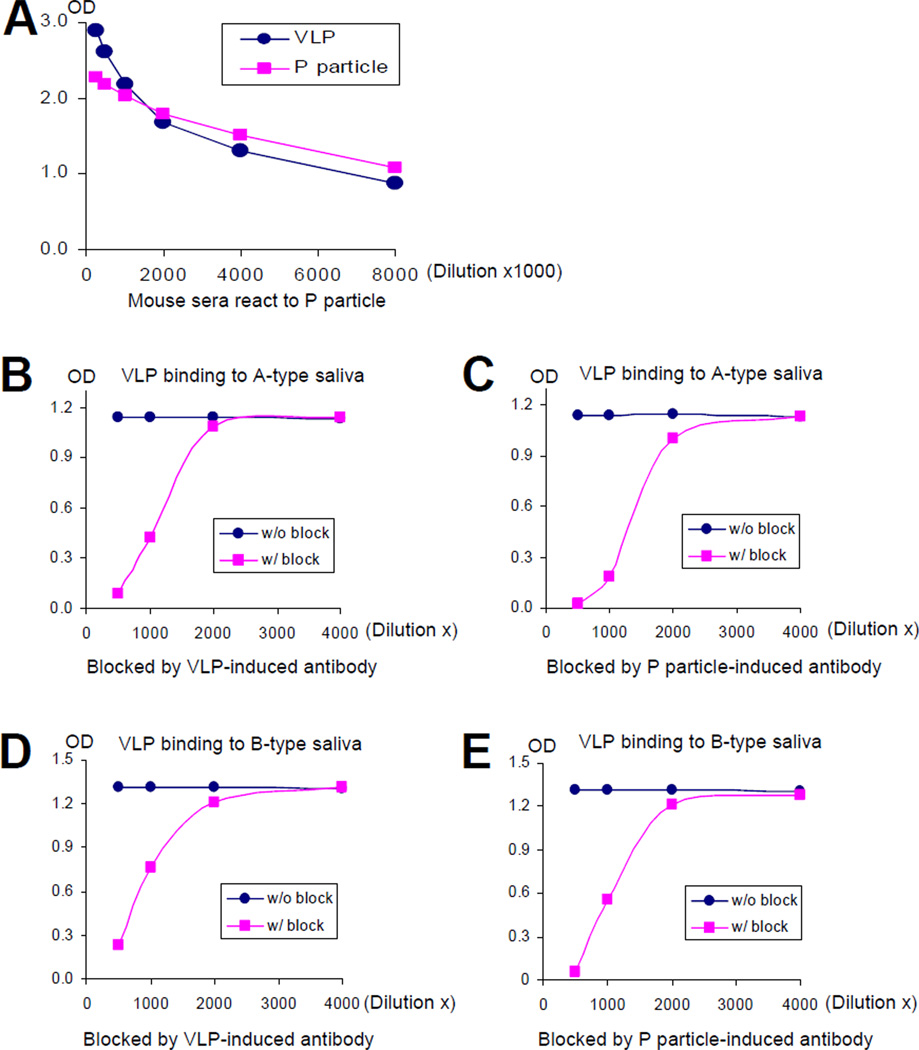

The P particle induces specific antibodies that block binding of VLP to HBGAs

A similar immunogenicity and antigenicity between P particles and VLPs has been demonstrated using hyperimmune antisera from mice immunized with VA387 P particles (n=3) and VLPs (n=3), respectively (Figure 6 and data not shown). With the same set of antisera we have demonstrated blocking activities of the antibodies in the binding of VLPs and P particles to their HBGA-receptors (Figure 6 and data not shown). These blocking activities were strain-specific as no blocking was detected on binding of HBGAs to heterologous strains (Norwalk virus, GI-1 and MOH, GII-5; data not shown). These data further suggest that noroviral P particles and VLPs may share the same surface conformation.

Figure 6.

P particle induced specific antibody in mice (A) that blocked VLP binding to HBGAs (B to E). A, both P particle and VLP of VA387 (GII-4) induced specific antibodies. Mice were immunized with VA387 P particle (n=3) and VLP (n=3) intranasally without adjuvant, respectively. The titers of the norovirus-specific antibodies were determined by Elisa using the P particle as antigen. B to E, both VLP- (B and D) and P particle- (C and E) induced antibodies blocked VA387 VLP binding to A- (B and C) and B- (D and E) type saliva. The lines with circle indicated VLP binding to saliva samples without blocking; the lines with square showed blocking effects by VLP-(B and D) and P particle- (C and E) induced sera. All results were average of triplicates.

Discussion

In this study using the cryo-EM technique we have elucidated the structures of the P particle which confirmed the spherical particles observed by EM in our previous study (Tan and Jiang, 2005b). The P particles are comprised of 12 P dimer subunits that are organized in octahedral symmetry. The dimeric packing of the proteins in the P particles is similar to that in the noroviral VLPs, in which the P1 subdomain serves the support, while the P2 subdomain as the outer surface of the P particle. Thus the P2-related antigenic epitopes and the receptor-binding interface on the VLPs should also be exposed on the P particles. These structural properties were supported by the functional analysis of the P particles, including their immunogenicity, antigenicity and in vitro receptor-binding functions in comparison with the VLPs. The observation that P particle induces norovirus-specific antibody that blocks binding of VLP to HBGA receptor also suggested that P particle may be a promising vaccine candidate against noroviral infection, particularly considering the fact that the P particles are much easier to obtain.

The structural analysis by cryo-EM also helped addressing questions regarding the formation and stability of P particles raised in previous studies (Tan and Jiang, 2005b; Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006). For example, the presence of the hinge inhibited P particle formation (Tan, Hegde, and Jiang, 2004; Tan and Jiang, 2005b). The crystal structure of noroviral capsid shows that the hinge is located at the base of the arch-like P dimer connecting to the interior shell (S) domain, providing certain flexibility between the S and the P domains (Prasad et al., 1999). In the P particle such flexibility is not necessary and thus the hinge plays no role but occupies space sterically, resulting in a stage unfavorable for the inter-P dimer interaction. In contrast, the cysteine residues that were linked to either end of the P domain strengthens the inter-P dimer interaction, most likely by forming inter-P dimer disulfide bonds (Tan and Jiang, 2005b). As a result, even the P domain with the hinge can form a stable P particle (Fig 2).

The C-terminal arginine (R)-cluster is another factor that affects the P particle formation is (Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006). The R-cluster is highly conserved and a removal of this R-cluster by trypsin in vitro disables the P particle formation (Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006) as well as receptor binding. This process may occur in vivo because trypsin is one of the major proteolytic enzymes in human gut and large amount of soluble P protein exist in the stool of norovirus-infected patient (Greenberg et al., 1981; Hardy et al., 1995). Noteworthy, the R-cluster containing C-terminus remains invisible in the crystal structures of norovirus capsids or P dimers (Bu et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2008; Prasad et al., 1999), probably owing to degradation or disorder of the C-terminal sequence. However, the C-terminus is believed to locate at the outer side and near the base of the arch-like P dimer and cryo-EM structure of the P particle showed that this is a critical region for inter-P dimer interaction, the major force for P particle formation. Thus, it is conceivable that the C-terminal R-cluster affects the P particle formation. However, it remains unknown how the R-cluster affects the HBGA-binding capability of the P particle.

Based on the data of structural analysis presented in this study the model of the P particle formation proposed in our previous study (Tan and Jiang, 2005b) needs to be updated. First, each P protein folds into a P monomer instantly after expression in the E. coli. This will result in the formation of the contacting interface required for the P dimer formation. Then the P monomers form arch-shaped P dimers automatically. These P dimers are morphologically similar to those in the VLPs and are expected to retain the same intra- and inter-molecular interaction in the P particle as one in the capsid. As a result 12 P dimers further assemble into an octahedral P particle through inter-P dimer interactions near the bases of each P dimer, in which the two legs of each arch-shape P dimers have to twist slightly to fit into the octahedron. In this process the presence of the hinge is a negative factor, while an intact C-terminus and an end-linked cysteine stabilized the P particle formation.

While the formations of P dimer is instant and highly efficient, the P particles formation is less efficient, which may be protein-concentration dependent (Tan and Jiang, 2005b). Although it remains unknown whether the P particle exists in vivo, the discovery that P protein forms P particles and the factors that favor or inhibit the P particle formation as well as stability could be important for understanding the morphogenesis of noroviral capsid and the role of the large amount of soluble P protein in vivo.

Noroviruses are still difficult to cultivate in vitro and the application of recombinant viral antigens in studies of virus-host interaction, diagnosis, and vaccine development has been an important approach. In this study we have demonstrated that the P particles share a number of surface properties with VLPs, therefore, they may be a useful substitute for VLPs in characterization of host/pathogen interaction. In addition, the P particles are much easier to produce in E. coli with a low cost [(Tan and Jiang, 2005b; Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006), and this report] than VLPs that can only be generated in a eukaryotic expression system, which is more complicated and time-consuming. P particles may be a common phenomenon of noroviruses because P particles from a number of other noroviruses have been produced, including the prototype Norwalk virus (GI-1), Boxer (GI-8), MOH (GII-5), VA207 (GII-9), and 16 different GII-4 strains [(Tan and Jiang, 2005b; Tan, Meller, and Jiang, 2006), this report, and unpublished data]. Recently the P particles have been successfully used in mutagenesis studies to elucidate the HBGA-binding interfaces of Norwalk virus and VA387 (Bu et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2008b). Thus the P particles would be a valuable addition to the molecular research on noroviruses.

Acknowledgement

The research described in this article was supported by the National Institute of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious diseases (R01 AI37093 and R01 AI55649) and National Institute of Child Health (PO1 HD13021), the Department of Defense (PR033018) to X.J., This work was also supported by the grant of Translational Research Initiative of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (SPR102032) to M.T. The cryo-EM images were taken in the Purdue Biological Electron Microscopy Facility and the Purdue Rosen Center for Advanced Computing (RCAC) provided the computational resource for the 3-D reconstructions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bu W, Mamedova A, Tan M, Xia M, Jiang X, Hegde RS. Structural basis for the receptor binding specificity of Norwalk virus. J Virol. 2008;82(11):5340–5347. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00135-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Lou Z, Tan M, Chen Y, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Zhang XC, Jiang X, Li X, Rao Z. Structural basis for the recognition of blood group trisaccharides by norovirus. J Virol. 2007;81(11):5949–5957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00219-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JM, Hutson AM, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Atomic resolution structural characterization of recognition of histo-blood group antigens by Norwalk virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(27):9175–9180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803275105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green K, Chanock R, Kapikian A. Human Caliciviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields Virology. 4th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 841–874. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg HB, Valdesuso JR, Kalica AR, Wyatt RG, McAuliffe VJ, Kapikian AZ, Chanock RM. Proteins of Norwalk virus. J Virol. 1981;37(3):994–999. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.3.994-999.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy ME, White LJ, Ball JM, Estes MK. Specific proteolytic cleavage of recombinant Norwalk virus capsid protein. J Virol. 1995;69(3):1693–1698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1693-1698.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heel MV. Similarity measures between images. Ultramicroscopy. 1987;21:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Farkas T, Marionneau S, Zhong W, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Morrow AL, Altaye M, Pickering LK, Newburg DS, LePendu J, Jiang X. Noroviruses bind to human ABO, Lewis, and secretor histo-blood group antigens: identification of 4 distinct strain-specific patterns. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(1):19–31. doi: 10.1086/375742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Farkas T, Zhong W, Tan M, Thornton S, Morrow AL, Jiang X. Norovirus and histo-blood group antigens: demonstration of a wide spectrum of strain specificities and classification of two major binding groups among multiple binding patterns. J Virol. 2005;79(11):6714–6722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6714-6722.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson AM, Airaud F, LePendu J, Estes MK, Atmar RL. Norwalk virus infection associates with secretor status genotyped from sera. J Med Virol. 2005;77(1):116–120. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson AM, Atmar RL, Graham DY, Estes MK. Norwalk virus infection and disease is associated with ABO histo-blood group type. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(9):1335–1337. doi: 10.1086/339883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindesmith L, Moe C, Marionneau S, Ruvoen N, Jiang X, Lindblad L, Stewart P, LePendu J, Baric R. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat Med. 2003;9:548–553. doi: 10.1038/nm860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, Chiu W. EMAN: semiautomated software for highresolution single-particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 1999;128(1):82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke SJ, Jakana J, Song JL, Chuang DT, Chiu W. A 11.5 A single particle reconstruction of GroEL using EMAN. J Mol Biol. 2001;314(2):253–262. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marionneau S, Cailleau-Thomas A, Rocher J, Le Moullac-Vaidye B, Ruvoen N, Clement M, Le Pendu J. ABH and Lewis histo-blood group antigens, a model for the meaning of oligosaccharide diversity in the face of a changing world. Biochimie. 2001;83(7):565–573. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, G. T. D., Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad BV, Hardy ME, Dokland T, Bella J, Rossmann MG, Estes MK. Xray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science. 1999;286(5438):287–290. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravn V, Dabelsteen E. Tissue distribution of histo-blood group antigens. Apmis. 2000;108(1):1–28. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Farkas T, Jiang X. Molecular Pathogenesis of Human Norovirus. Chapter 24. In: Yang DC, editor. RNA Virus: Host Gene Responses to Infection. 1 ed. New Jersey, London, and Singapore: World Scientific; 2008. pp. 575–600. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Hegde RS, Jiang X. The P domain of norovirus capsid protein forms dimer and binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol. 2004;78(12):6233–6242. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6233-6242.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Huang P, Meller J, Zhong W, Farkas T, Jiang X. Mutations within the P2 domain of norovirus capsid affect binding to human histo-blood group antigens: evidence for a binding pocket. J Virol. 2003;77(23):12562–12571. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.23.12562-12571.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Jiang X. Norovirus and its histo-blood group antigen receptors: an answer to a historical puzzle. Trends Microbiol. 2005a;13(6):285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Jiang X. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol. 2005b;79(22):14017–14030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14017-14030.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Jiang X. Norovirus-host interaction: implications for disease control and prevention. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2007;9(19):1–22. doi: 10.1017/S1462399407000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Jin M, Xie H, Duan Z, Jiang X, Fang Z. Outbreak studies of a GII-3 and a GII-4 norovirus revealed an association between HBGA phenotypes and viral infection. J Med Virol. 2008a;80(7):1296–1301. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Meller J, Jiang X. C-terminal arginine cluster is essential for receptor binding of norovirus capsid protein. J Virol. 2006;80(15):7322–7331. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00233-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Xia M, Cao S, Huang P, Meller J, Hegde R, Li X, Rao Z, Jiang X. Elucidation of strain-specific interaction of a GII-4 norovirus with HBGA receptors by site-directed mutagenesis study. Virology. 2008b doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.06.041. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Zhong W, Song D, Thornton S, Jiang X. Ecoli-expressed recombinant norovirus capsid proteins maintain authentic antigenicity and receptor binding capability. J Med Virol. 2004;74(4):641–649. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorven M, Grahn A, Hedlund KO, Johansson H, Wahlfrid C, Larson G, Svensson L. A homozygous nonsense mutation (428G-->A) in the human secretor (FUT2) gene provides resistance to symptomatic norovirus (GGII) infections. J Virol. 2005;79(24):15351–15355. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15351-15355.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]