Abstract

Background

The US Institute of Medicine has recommended an integrated, locally sensitive collaboration among the various members of the community, health care systems, and research organizations to improve dementia care and dementia research.

Methods

Using complex adaptive system theory and reflective adaptive process, we developed a professional network called the “Indianapolis Discovery Network for Dementia” (IDND). The IDND facilitates effective and sustainable interactions among a local and diverse group of dementia researchers, clinical providers, and community advocates interested in improving care for dementia patients in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Results

The IDND was established in February 2006 and now includes more than 250 members from more than 30 local (central Indiana) organizations representing 20 disciplines. The network uses two types of communication to connect its members. The first is a 2-hour face-to-face bimonthly meeting open to all members. The second is a web-based resource center (http://www.indydiscoverynetwork.org ). To date, the network has: (1) accomplished the development of a network website with an annual average of 12,711 hits per day; (2) produced clinical tools such as the Healthy Aging Brain Care Monitor and the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale; (3) translated and implemented the collaborative dementia care model into two local health care systems; (4) created web-based tracking software, the Enhanced Medical Record for Aging Brain Care (eMR-ABC), to support care coordination for patients with dementia; (5) received more than USD$24 million in funding for members for dementia-related research studies; and (6) adopted a new group-based problem-solving process called the “IDND consultancy round.”

Conclusion

A local interdisciplinary “think-tank” network focused on dementia that promotes collaboration in research projects, educational initiatives, and quality improvement efforts that meet the local research, clinical, and community needs relevant to dementia care has been built.

Keywords: cognitive impairment, community research, translational research, complex adaptive system

Introduction

Significant breakthroughs in basic research on the pathophysiology of dementing disorders and new innovative models of dementia care hold the promise of reducing the future burden of dementia.1 However, the majority of dementia research is conducted in specialized research centers among patients who represent less than 1% of the patient population with dementia, with ethnic minority groups being largely underrepresented.2–6 Furthermore, the translation of innovative research discoveries into clinical practice typically takes an average of 17 years and the current research infrastructure fails to shorten this translational cycle.7 The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Roadmap and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recognized the large gap in translating research innovations from discovery to delivery and recommended “re-engineering of the clinical research enterprise.”8–10

The IOM and the NIH Roadmap recommended the use of complex adaptive system perspectives and information technology to build a localized and cohesive collaboration among the various members of the community, health care systems, and research organizations.8–10 In response to the IOM and the NIH recommendations, the Regenstrief Institute, Inc, the Indiana University Center for Aging Research (IUCAR), and the Indiana Alzheimer Disease Center have been building a network of health care providers, clinical researchers, and community advocates dedicated to enhancing the quality of life and care of individuals with dementia and the life and care of their informal caregivers. The network is called the “Indianapolis Discovery Network for Dementia” (IDND).11 The IDND has created an environment that supports exchanges of information and ideas among its diverse and autonomous individuals, allowing the network to accomplish its three-fold mission of facilitating the development of rapid, innovative health care solutions that meet local research, clinical, and community needs; promoting a culture of discovery, cooperation, and teamwork among its diverse members; and disseminating novel and effective dementia care knowledge within the various health care systems in Indianapolis.

This article describes the theoretical framework, process, tools, and early successes of the IDND network, which we believe could help facilitate the building of similar dementia networks in other regions of the USA.

Methods

Theoretical framework

Complex adaptive system theory was selected to guide the structuring and development of a social network focused on reducing the societal burden of dementia by connecting local research activities with local dementia care delivery systems.11–19 A “complex adaptive system” is an open, dynamic, and flexible network that is considered “complex” due to its composition of numerous interconnected, semiautonomous, competing, and collaborating members.13–16 This complex network is capable of learning from its prior experiences and is flexible to change the connecting pattern of its members to better fit its environment and accomplish its various missions and tasks.13–18 Furthermore, complex adaptive systems are characterized by emergent behaviors as opposed to predetermined behaviors and self-organized controls instead of hierarchical controls.13–18 Health care delivery organizations, universities, and internet-based social networks are considered examples of complex adaptive systems.6,11–19

To organize, facilitate, and sustain effective interactions among the network’s autonomous members, we applied the nine emerging and connected organizational and leadership principles of complex adaptive system theory:20

View the social network as a complex adaptive system. The members of such a social network are semiautonomous, interdependent, competitive, and collaborative individuals who interact in a nonlinear way leading to the emergence of unpredictable behaviors.

Work on building an acceptable and flexible vision for the network with minimum specifications rather than having a detailed and rigid operational manual.

Direct and guide the network dynamics and interactions by balancing data and intuition, planning and acting, safety and risk.

Encourage and promote a balance of information exchange, connection channels, diversity, power differential, and tension among network members instead of controlling information exchange, forcing agreement, and dealing separately with contentious groups. Avoid systematically working down all the layers of the hierarchy in sequence and seeking comfort.

Uncover and encourage unpredictability and tension rather than shying away from them.

Go for multiple actions at the fringes. Let direction arise rather than micro-planning every step and searching for the highest level of linearity.

Listen to the informal relationships, gossip, rumors, and hallway conversations that contribute significantly to individuals’ perceptions about their surrounding environment and their subsequent actions.

Allow complex subnetworks to emerge out of the links among simple networks that work well and are capable of operating independently.

Build a community of members who collaborate, create, learn, and compete simultaneously.

Building on these principles, we chose to incorporate reflective adaptive process (RAP) as a practical method focused on using complex adaptive system principles to introduce acceptable and effective change.12,14,17 RAP facilitates the development of strategies, not prescribed protocols, and change built on explicit opportunities for learning, reflection, and adaptation. The five guiding principles of RAP are:

Vision, mission, and shared values are fundamental in guiding ongoing change processes in a complex adaptive system.

Creating time and space for learning and reflection is necessary for a complex adaptive system to adapt to and plan for change.

Tension and discomfort are essential and normal during complex adaptive system changes.

Improvement teams should include a variety of the system’s agents with different perspectives of the system and its environment.

System change requires supportive leadership that is actively involved in the change process, ensuring full participation from all members and protecting time for feedback and reflection17 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Applying the reflective adaptive process to the development of IDND

| Principle | Local application |

|---|---|

| Shared values are fundamental in guiding ongoing change processes in a CAS. | The interdisciplinary network would (a) facilitate the execution of quality improvement and clinical research activities that meet the local research, clinical, and community needs; (b) promote a culture of discovery, cooperation, and team work among its diverse members; and (c) disseminate knowledge and innovations in dementia care. |

| Creating time and space for learning and reflection to adapt and plan change. | Bimonthly face-to-face meetings and web-based resource center. |

| Tension and discomfort are normal in introducing a change within a CAS. | The IDND consultancy round provides a structure to facilitate discussion, feedback, and review. |

| Improvement team should include a variety of system’s agents with different perspectives of the system and its environment. | IDND membership is comprised of an interdisciplinary matrix of people with variety in relevant roles, expertise, skills, and perspectives. It includes geriatricians, neurologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers, public health officers, health administrators, clinical researchers, and medical informaticians. |

| System change requires supportive and active leadership. | IDND has leadership representatives from the five health care systems in Indianapolis, the Alzheimer associations, and Indiana Minority Health Coalition. |

Abbreviations: CAS, Complex Adaptive System; IDND, Indianapolis Discovery Network for Dementia.

Development process

The IDND development process began with the formation of a cross-functional operational team consisting of the network director and coordinator and representatives from both academic and nonacademic memory care practices. Our operational team used iterative cycles to identify priority improvement opportunities, discuss potential solutions, pilot several changes, and reflect on the impact of changes.

Membership

The IDND network director and coordinator explored existing relationships with local professionals to identify potential members who shared the goals of the network and practiced within the Indianapolis metropolitan area. Membership was open to those in various disciplines, such as physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers, health care administrators, pharmacists, and public health officers, including representatives of the major health care systems in the metropolitan area: Wishard Health Services, Indiana University Health, St Vincent Health and Hospital, the Community Health Network, and Saint Francis Health Care. In addition, the Alzheimer’s Association of Greater Indiana and the Indianapolis Minority Health Coalition participate as representatives of local advocacy organizations. Representatives from other local pharmaceutical companies or for-profit organizations who shared an interest in the goals and objectives of the network were not excluded from membership.

The consultancy model

The IDND consultancy round, which is part of the bimonthly meeting, offers structured time and space for the generation and sharing of innovative ideas, potential solutions, and member-to-member shared perspectives and support. This group-based problem-solving process is a modified version of a peer-to-peer advisory activity that was developed by The John A Hartford Foundation to support interaction between the foundation’s interdisciplinary grantees and scholars.21 The IDND consultancy round part of the bimonthly meeting is limited to 60 minutes, and has the following six specifications:

Prior to each meeting, an IDND member selects a clinical, educational, or research challenge for which he/she would like to seek feedback on from other members.

The presenter has up to 15 minutes to present his/her selected challenge using a typical oral presentation with or without the use of slideshow software or other media.

Meeting attendants have up to 5 minutes to ask clarifying questions related to the presented challenge.

Approximately 2 minutes is allotted to each IDND member who would like to provide solutions or feedback to the presenter; each IDND member is encouraged to provide a solution and no IDND member can criticize or respond to any of the feedback or solutions presented by other IDND members.

The presenter will have up to 5 minutes to summarize the feedback received; he/she cannot respond to suggestions from the IDND members.

Following the feedback summary, the group will have an open discussion regarding the themes generated from the consultancy round.

The IDND coordinator records all of the solutions and shares them with the presenter and other IDND members upon request.

In each IDND meeting, there is a 30-minute period before and 30-minute period after the consultancy round that are designed to enhance social interaction and networking among members. During this time, the network director introduces new members and briefly celebrates IDND members’ recent accomplishments. For the IDND, the director also serves as the meeting facilitator, responsible for monitoring the process of the IDND consultancy round, gathering information generated during the meetings, and encouraging participation and self-reflection. This includes the active solicitation of feedback from all members – at minimum, feedback from a recognized leader who can speak on behalf of their own profession or specialty. This can be a challenge for larger networks and requires a leader who is not only well respected and sensitive to the needs of all group members but also who can create a comfortable environment. The role of the facilitator is not specifically allocated to the network director, so can be held by another member supported by the network’s IDND Governing Body and members.

Results

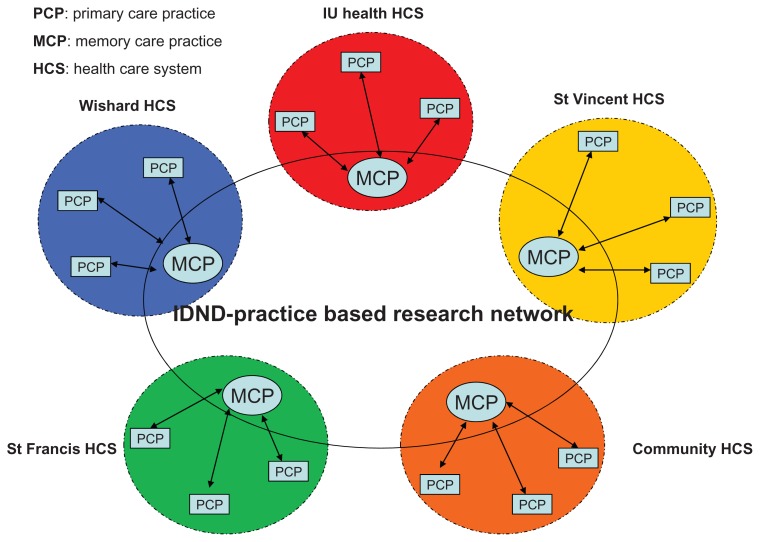

Today, the IDND includes more than 250 members representing 20 disciplines and more than 30 local organizations (see Table 2). Since its inception in February 2006, the IDND has conducted over 30 consultancy rounds, presented by 20 different members, that have covered educational, research, and clinical problems. It incorporates both leadership and “front-line” representation from the disciplines of clinical medicine, economics, research, biostatistics, information technology, and marketing. The IDND has members from eight memory care practices representing five of the different Indiana health care systems. The model of dementia care within each memory care practice varies, with some clinics having a dedicated dementia care nurse specialist while others have both a nurse and a social worker with expertise in dementia care (see Figure 1). Two of these memory care practices have successfully translated the collaborative dementia care model into self-sustained clinical services.22

Table 2.

Characteristics of IDND members

| Members and practices | |

| Total number of members | 250 |

| Total number of practices, clinics | 8 |

| Total number of patients served | 5000 |

| Profession | |

| Physicians | 66 |

| Nurse practitioners | 15 |

| Physician assistants | 2 |

| Other clinicians | 100 |

| Other members | 67 |

| Physician specialties | |

| General internal medicine | 30 |

| Other: neurology, psychiatry, geriatrics | 40 |

Abbreviation: IDND, Indianapolis Discovery Network for Dementia.

Figure 1.

IDND-practice based research network.

Abbreviations: HCS, health care system; IU, Indiana University; MCP, memory care practice; PCP, primary care practice; IDND, Indianapolis Discovery Network for Dementia.

Research projects and clinical tools

The IDND has also facilitated the recruitment and execution of more than ten research projects that have been awarded more than USD$24 million dollars in funding and have recruited more than 2500 participants (see Table 3). Furthermore, IDND-supported projects and educational opportunities have resulted in the development of multiple clinical tools, including the Healthy Aging Brain Center (HABC) Monitor, enhanced Care for Hospitalized older Adults with Memory Problem (e-CHAMP) delirium protocols, Recognizing and Assessing the Progression of cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Primary Care (RAPID-PC) assessment cards, and the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden (ACB) Scale available for professionals online through the IDND website’s resource center. The first and last of these – the HABC Monitor and the ACB Scale – are two of the most successful products of the IDND’s collaborative efforts. These and the Enhanced Electronic Medical Record for Aging Brain Care (eMR-ABC) are discussed following.

Table 3.

Funding for IDND supported projects

| Project titles | Total award amount |

|---|---|

| ADMIT: Alzheimer’s Disease Multi Intervention Trial | $2,706,383 |

| PROSPECT-COMET: Prospective Outcome Systems Using Patient-Specific Electronic Data to Compare Tests and Therapies-Comparative Effectiveness Research Trial of Alzheimer’s Disease Drug | $8,422,410 |

| PRISM-PC: Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory Problems in Primary Care | $872,263 |

| Healthy Aging Brain Care Monitor (HABC-Monitor) via a research grant from FOREST PHARMACEUTICALS | $222,000 |

| Enhanced Medical Record for Aging Brain Care via a research grant from NOVARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS | $226,200 |

| HABC MONITOR via Indiana University Roybal Center for Translational Research on Aging | $61,730 |

| IN-PEACE: Indiana Palliative Excellence in Alzheimer Care Efforts | $154,000 |

| CHIP: Cognitive Health in Indianapolis Project | $2,846,877 |

| IADC: Indiana Alzheimer Disease Center | $8,817,465 |

| IPRISP: Indianapolis Interventions and Practice Research Infrastructure Program | $456,018 |

| Total | $24,785,346 |

Note: Total Award Amount = US$.

HABC Monitor

In hypertension care, the blood pressure cuff is a tool used for screening, diagnosis, and monitoring. Based on the “blood pressure cuff” concept, the HABC Monitor was developed to function similarly in dementia care: one instrument capable of achieving all three processes. The development of the HABC Monitor was based on data collection from our previous studies5,22 and its face validity tested using the feedback of an interdisciplinary team of 22 representatives from three disciplines – clinical care, clinical research, and psychometrics – who were involved in dementia care and research. There are two versions of the monitor, the HABC Caregiver and HABC Self-Report, both of which are actively used in several of our local affiliated memory care practices.

ACB scale

The literature strongly supports the increased risk of acute cognitive impairment and possibly chronic cognitive impairment in older adults using anticholinergic medications. While physicians are aware of the side effects of drugs within the anticholinergic category, many may not recognize the anticholinergic properties of drugs new to the market or those with unrecognized anticholinergic properties. To assist with the recognition of these medications, our interdisciplinary team developed the ACB scale as a practical tool that identifies the severity of anticholinergic effects from both prescription and over-the-counter medications on cognition.

eMR-ABC

One of the largest and longest-term development projects of the IDND has been the construction of the eMR-ABC, a web-based medical record system that meets the needs of dementia research and care. As a first step in building the eMR-ABC, the IDND consulted with the leadership of IUCAR and the Regenstrief Institute, Inc, and organized two meetings with all IDND clinical providers in an effort to understand the providers’ perspectives about potential barriers to eMR-ABC. The meetings with the clinical providers identified the following critical elements necessary to build an efficient and successful eMR-ABC:

Clinicians and researchers need to identify potential patients with dementia using criteria that represent a community standard.

Clinicians and researchers need to reach consensus on the data elements relevant to both dementia care and research that should be collected, stored, and tracked.

The eMR-ABC must store and safeguard data in a consistent format using accepted standards.

The eMR-ABC must be able to transmit dementia-related data in a standardized format.

The eMR-ABC must incorporate tools that are feasible and familiar to all personnel involved in collecting the data.

The eMR-ABC must be governed by an interdisciplinary operations team.

The IDND has successfully completed a pilot test of its eMR-ABC in one health care system and has received additional funding to upgrade the current program and continue further testing on a larger scale to assure its: capability in capturing reliable data related to dementia care and outcomes; ability in managing, summarizing, and presenting captured data to various eligible researchers and clinicians; and ability in facilitating dementia research activities by identifying potential subjects for various studies and tracking their health outcomes.

IDND website

Over the past 12 months, the IDND website has been redesigned to improve its user interface, offer more resources, and create an additional environment for networking among members. The website serves as an open-source repository for network members and the public, providing an array of information including past dinner presentations, links to external resources for both the patient and the caregiver, IDND products such as the HABC Monitor and the ACB Scale, calendar of events for both IDND and community and clinic collaborators, and interesting articles and journal publications related to dementia research and care. The website also offers its members the opportunity to list information on the website about the clinics, facilities, and organizations they represent. The website receives an average of 12,000 hits and 600 visits per day. Although the IDND consists primarily of local members, the website allows wider access to the IDND.

IDND core groups

Additionally, IDND’s continued expansion and the growing needs of dementia research prompted the development of two core groups within IDND: the IDND Governing Body and the Patient Advisory Board. Both groups were established to assist the Operational Body – which includes the network director, associate director, and the assistant network director – in the decision-making processes of the network. The IDND Governing Body consists of 15 members divided into three subgroups: Memory Care Practice (six positions); Long-Term Care (one position); and Elected (eight positions), which is comprised of experts in information technology, law, finance, education, and public relations. The Governing Body also contains five subcommittees: Education, Clinical Practice and Implementation Guidelines, Research and Implementation, Governance, and Finance and Accountability. Each subcommittee is directed by a chair and vice chair elected by the Governing Body members. Members of the first Governing Body were selected and voted for by the core members of IDND, who were instrumental in its early development. To facilitate its function, the Operational Body also created “Guidelines for the Governing Body,” which includes position and term definitions, voting protocols, its role in assisting the network in maintaining the network’s values and meeting its mission and goals. The Governing Body meets quarterly throughout the year and is directed by two people, a nominated chair and vice chair.

The Patient Advisory Board was developed to add a unique perspective to the consultancy round as well as to respond to new requests by federal funders for the addition of patient/caregiver input on the design and implementation of new dementia research that may influence patients and caregivers health outcomes. The IDND Patient Advisory Board comprises eight patients and their caregivers. As active members, they are asked to attend the regular IDND consultancy dinners.

Development of a practice-based research network (PBRN)

As the IDND continues to expand, one step in its growth is to help IDND’s member memory practices form a PBRN. PBRNs offer advantages to both research and quality improvement initiatives, having the ability to move scientific advances into daily practice quickly and to incorporate practice-relevant topics into the research agenda.7 Most recently, the US Department of Health and Humans Services’ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recognized the IDND as an affiliate primary care PBRN.

Discussion

Within the last 6 years, the IDND has been a competitive force in the development and delivery of new and innovative dementia care research. In turn, research founded and supported by the IDND has yielded multiple journal publications and invitations to present work at seminars and conferences throughout the nation. Despite early successes, the IDND has not been paralyzed by its early achievements but has preserved its momentum and is continuing to evolve to meet the changing needs of the community it serves.

As the IDND moves forward in creating and achieving new goals, it has much to learn about the history and successes of other community- and practice-based research networks. Although the infrastructures of Contract Research Organizations and PBRNs vary widely, they do share some common elements. Both have a mission statement, a director, support staff, communication processes, and a community advisory board.23,24 As the membership and diversity of the IDND have continued to grow, the network has been successful in its rigorous adherence to its original mission and goals while maintaining complexity. As with other community research networks, the IDND’s mission and goals are narrow and specific. The IDND’s primary focus is dementia research and dissemination.

However, the research supported by the IDND has been conceptualized, executed, and led largely by the IDND network director; collaborative efforts among the IDND group members have been limited to recruitment and dissemination. This is not due to a lack of support from the IDND leadership in encouraging IDND members to explore their own research interests; rather, it is perhaps due to lack of guidance. Within the last year, the network responded to this by establishing a governing body and patient advisory board to assist members at any point along the research timeline (ie, grant proposal, study design, recruitment, data collection and analysis, and implementation).

As already outlined, the IDND Governing Body and Patient Advisory Board were developed to guide the IDND members in their research development and implementation. Unlike other research networks with elaborate leadership panels and established bylaws, the Governing Body and Advisory Board have limited decision-making power. Guidelines were developed but only to document the developmental process of the Governing Body and Patient Advisory Board and to define the roles of each for the network members. It is at the discretion of the investigator and research study team to respond to advice given. Although not a requirement among all community networks, patient representation within the IDND ensures patient input in the decision-making process and project development. Unlike other patient advisory boards, which are restricted to patients only or patients with specific forms of dementia or disease, the IDND’s definition of “patient” includes the informal caregiver, allowing the IDND to develop research that addresses the needs of both. Although the functions of the Governing Body and Patient Advisory Board for IDND continue to be defined, even in their juvenile state, both groups have already made significant contributions to the IDND.

For most networks, funding is a constant obstacle, which can limit the degree of size, outreach, and direction of network growth.25 The IDND is sponsored by the Regenstrief Institute, Inc, and IUCAR, which support the bimonthly meetings and the administrative infrastructure of the network. Any research grants, educational programs, or quality improvement projects generated by a member of the network are routed via the member-affiliated organizations. These organizations either receive the grants directly or operationalize the educational or clinical program. The network has functioned as a facilitator or catalyst for grant generation and clinical or educational program development. Other research networks, such as the Alzheimer’s Association of Indianapolis, have sponsors and additional financial partners, which allows for flexibility, increased involvement, and a larger societal impact. Although the IDND has the interest and representation of the major health care systems in the Indianapolis area, exploration of additional funding is necessary to translate the IDND into a national model for the building of regional and national dementia networks.

Communication tools vary among networks and include email LISTSERVs, newsletters, websites, and face-to-face meetings.23 For the IDND, information exchange has been unidirectional, primarily through email, newsletters, and the IDND website. With the exception of the regular dinner meetings, most IDND members do not have other opportunities to communicate with the IDND administration and other network members. The use of message boards and e-newsletters has been instrumental for other research networks in increasing information exchange among their members, gaining the interest of new parties, and expansion of research.

Conclusion

Although the IDND has had many successes within its first years of operation, further development is needed in the financial and communication facets of the network as well as increased research proposition and involvement from other members to ensure longevity and lifelong societal impact. Improvements in these areas will result in opportunities for regional and national recognition and the translation of the IDND model into the building of other dementia discovery networks. These regional networks would be the ideal testing ground for new ideas and technologies for primary, secondary, and tertiary dementia prevention, creating more opportunity for collaborative research projects, quality improvement, and global impact.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the IDND.

The work was supported by a Paul A Beeson Career Development Award in Aging (K23 AG 26770-01) from the National Institute on Aging, The John A Hartford Foundation, the Atlantic Philanthropies, and the American Federation of Aging Research; two individual grants from the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG-10133) (P30 AG-024967); and a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01 HS019818-0).

Footnotes

Disclosure

Other than the funding outlined in the Acknowledgments, the authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. 2. Vol. 8. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2012. pp. 1–72. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faison WE, Mintzer JE. The growing, ethnically diverse aging population: is our field advancing with it? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(7):541–544. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.7.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faison WE, Schultz SK, Aerssens J, et al. Potential ethnic modifiers in the assessment and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: challenges for the future. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(3):539–558. doi: 10.1017/S104161020700511X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan CM, Boustani MA. After the end of free fall: geriatricizing primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):142–143. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0847-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boustani M, Sachs G, Callahan CM. Can primary care meet the biopsychosocial needs of older adults with dementia? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1625–1627. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0386-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callahan CM, Weiner M, Counsell SR. Defining the domain of geriatric medicine in an urban public health system affiliated with an academic medical center. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1802–1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research – “Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297(4):403–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institutes of Health (NIH) NIH Roadmap for Clinical Research: Clinical Research Networks and NECTAR [webpage on the Internet] Bethesda, MD: NIH; nd. [Accessed July 12, 2012]. Available from: http://commonfund.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-networks.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zerhouni E. Medicine. The NIH Roadmap. Science. 2003;302(5642):63–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1091867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Indianapolis Discovery Network for Dementia [homepage on the Internet] [Accessed July 12, 2012]. Available from: http://www.indydiscoverynetwork.org.

- 12.Boustani MA, Munger S, Gulati R, Vogel M, Beck RA, Callahan CM. Selecting a change and evaluating its impact on the performance of a complex adaptive health care delivery system. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:141–148. doi: 10.2147/cia.s9922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plsek PE. Working Paper: Some Emerging Principles for Managing in Complex Adaptive Systems. Roswell, GA: Paul E Plsek and Associates, Inc; 1997. [Accessed July 12, 2012]. Available from: http://www.directedcreativity.com/pages/ComplexityWP.html#CAS. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDaniel RR, Jr, Jordan ME, Fleeman BF. Surprise, Surprise, Surprise! A complexity science view of the unexpected. Health Care Manage Rev. 2003;28(3):266–278. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lansing SJ. Complex adaptive systems. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2003;32:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holden LM. Complex adaptive systems: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(6):651–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stroebel CK, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Nutting PA, Stange KC. How complexity science can inform a reflective process for improvement in primary care practices. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(8):438–446. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews JI, Thomas PT. Managing clinical failure: a complex adaptive system perspective. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2007;20(2–3):184–194. doi: 10.1108/09526860710743336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman B, Lindberg C, Plsek P. Edgeware: Insights from Complexity Science for Health Care Leaders. Curt Lindberg; Irving, Texas: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerman B, Lindberg C, Plsek P. Edgeware: Lessons from Complexity Science for Health Care Leaders. Dallas, TX: VHA Inc; 1998. Nine emerging and connected organizational and leadership principles; pp. 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The John A Hartford Foundation. Grants and strategy [web page on the Internet] New York, NY: The John A Hartford Foundation; nd. [Accessed July 12, 2012]. Available from: http://www.jhartfound.org/grants-strategy. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boustani MA, Sachs GA, Alder CA, et al. Implementing innovative models of dementia care: The Healthy Aging Brain Center. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(1):13–22. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.496445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green LA, White LL, Barry HC, Nease DE, Jr, Hudson BL. Infrastructure requirements for practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(Suppl 1):S5–S11. doi: 10.1370/afm.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) AHRQ Primary Care Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN) Initiative [web page on the Internet] Rockville, MD: AHRQ; nd. [Accessed July 11, 2011]. Available from: http://pbrn.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt/community/practice_based_research_networks_%28pbrn%29. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pulcini J, Sheetz A, DeSisto M. Establishing a practice-based research network: lessons from the Massachusetts experience. J Sch Health. 2008;78(3):172–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]